Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Journal of Human Growth and Development

Print version ISSN 0104-1282

Rev. bras. crescimento desenvolv. hum. vol.25 no.2 São Paulo 2015

https://doi.org/10.7322/JHGD.102999

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Young offenders in brazil: mental health and factors of risk and protection

Maria Denise Pessoa e SilvaI; Thelma Simões MatsukuraI; Maria Fernanda Barboza CidI; Martha Morais MinatelII

IDepartment of Occupational Therapy, Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar)

IIFederal University of Sergipe (UFS)

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The literature has indicated that young offenders may show varied problems of mental health; however, in Brazil a limited number of studies are focused on that question

OBJECTIVE: Identify the health, self-esteem and social support levels of male young offenders complying with not confined socio-educational measures, the parenting styles adopted towards them and identify the relationship between these variables

METHODS: It is an exploratory and correlational study in which 33 male young offenders aged between 14 and 18 years who attend the socio-educational programme of a mid-size city in the State of São Paulo, Brazil, took part on the study, they answered specific instruments to appraise different variables of focus

RESULTS: The results indicate that 67% of the adolescents presented mental health disorders; 84% perceive that the social support received is below "low" or "medium", and 33% judge the parental style of their caregiver as a risk. The greater the negligence and poor support of the family and caregivers, the lower the self-esteem of young offenders

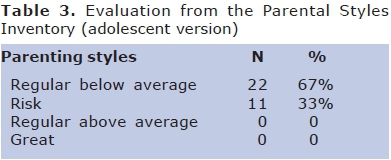

CONCLUSIONS: Most of the adolescents had mental health disorders and evaluated the social support received as low or medium. All participants evaluated negatively the parental style adopted by their parents. The parental style used was considered below average and risky. Furthermore, was observed that the lower the self-esteem of the adolescents and the lower the family support perceived by them, the higher was the degree of parental negligence evaluated. It is understood that these results reinforce the need for intersectoral coordination in actions aimed at this population

Key words: young offenders, mental health, social support, risk and protection

INTRODUCTION

Considering the elements that influence human development, we highlight those that can act as support to the healthy development of the individual and others that can harm his well-being, identified respectively as protective factors and risk factors1.

Risk factors are considered to be conditions and variables related to the occurrence of negative effects on development of a particular individual, whether they are related to impairment of health or social performance. It is noteworthy that, even more important than the impact of a single risk factor on an individual's development, is the combination of adversities, since the sum and interaction of various risk factors can further expose the individual, who becomes more vulnerable to the onset of a disorder of his health or behaviour1,2.

Aiming at adolescents and risk factors, authors point out that elements such as poverty, poor education, drug use, exposure to violence and hostility in the family environment can not only make the adolescent vulnerable but also predispose one to criminal behaviour and, thus, compel one to comply with the sanctions under law3.

In addition to the studies that seek to understand risk factors, there are Brazilian studies aiming to identify the characteristics, family, health and social phenomena that permeate the lives of adolescents involved in criminal acts4-6.

Priuli and Moraes6 surveyed the socio-demographic, criminal and relational profile of 48 adolescents aged between 14 and 18 years interned at Welfare of Minors Foundation (Fundação do Bem-Estar do Menor - FEBEM) in São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo - Brazil in 2003. By analyzing the files of those adolescents, it was found that 35.4% of adolescents were aged 17 years. Regarding the instructional level, 68.7% of adolescents had incomplete elementary education while 83.3% did not attend school6.

Gallo and Williams4, when describing the profile of adolescents in conflict with the law, highlighted the following: violation of social norms, behaviour at odds with the culture in which they live, socialization difficulties, early use of licit and illicit drugs, history of aggression, participation in fights, impulsive behaviour, depressed mood, suicide attempts, no guilt, hostility, public equity damage, institutionalization, vandalism, rejection in his social circle, relationships with colleagues who have deviant behaviour, low income and truancy4.

In accordance with Brazilian studies, international studies also indicate that young offenders have low education and low socio-economic status, truancy, early involvement with cigarettes, alcohol and narcotic substances, mental health disorders and early practice of criminal conduct7-9. Thus, we observe that the literature has pointed out several features of juvenile offenders that relate to the field of mental health.

Oliván conducted a bibliographic review on the topic of offending among adolescents in order to provide an update on the mental health issues that affect this population and health programmes to address this demand. The author points out that 63% of the studies found were conducted in the United States, 24% are publications from Western Europe (Spain, UK, Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden and Finland), 8% were conducted in Australia and 5% in Canada. Still, the author indicates that, qualitatively, differences among most incident disorders in young people were not found and that all the studies emphasize the importance and the need for health services aimed at meeting this population8.

Teplin et al9. conducted a study on the Temporary Detention Center for Youth in Cook, Illinois, United States. The researchers aimed to investigate the prevalence of mental health disorders in that population; however, they emphasize another purpose: to overcome the methodological limitations of previous studies, such as the use of restricted samples and non-validated instruments as well as poorly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The sample consisted of 1,829 adolescents aged 10 to 18 years, randomly selected. The results of this study indicated that approximately two-thirds of adolescent boys and three-quarters of adolescent girls presented one or more psychiatric problems, namely: affective disorders, anxiety, psychosis, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, disruptive behaviour disorders and substance use9.

In Brazil, some studies of psychiatric disorders among young offenders were conducted10-12.

Silva and colleagues investigated the prevalence of mental disorders in a population of 99 male young offenders and 47 female young offenders in the city of Rio de Janeiro and found a high incidence of psychiatric disorders in this sample. The authors point to the inefficiency of public health care in mental health in childhood and adolescence and indicate that gaps in the diagnosis of mental health disorders can harm adolescents' health care and corroborate the recidivism in criminal behaviour. They also indicate that there are few studies on the prevalence of mental health disorders among Brazilian young offenders, pointing to the need for investment in the area10.

Brazilian studies involving the investigation of mental health disorders in adolescents in conflict with the law are still limited. Moreover, the results from those studies indicate significant variations in results. Such variations may be associated with the different evaluation tools used, but may also be due to other variables such as sample of adolescent females and males, comparing offenders who committed different crimes categorized as serious and non-serious and composition of samples quantitatively different from each other, among others.

Investigations focusing on Brazilian adolescents involved in infraction experience and the mental health of this population, considering the peculiarities of this group, the specific national situation, are still needed.

They should also highlight the mental health of young people and identify risk and protective factors. Even after many years of implementation of socio-educational proposals and despite the results achieved to date, it is undeniable that we are facing a challenge that involves a complex multifactorial phenomenon13. In this sense, it is understood that the search for elements of the different natures and fields that are involved must add to the process and not divert the focus of attention or give a more individualized procedure that implies social and/or governmental irresponsibility. Thus, it is understood that the sum and integration of various fields of knowledge should compose the understanding and reflection and propose more effective actions13.

Based on these, the objective of this study is to identify the health, self-esteem and social support levels of male young offenders complying outdoor socio-educational measures, parenting styles adopted to them and identify the relationship between these variables.

METHODS

It is exploratory and correlational study. The contextual variables considered for assessing relationships with mental health levels of the participants were: adolescents' self-esteem, parenting styles adopted by parents evaluated by adolescents and social support of adolescents.

Participants

Were 33 male adolescents attending a not confined socio-educational program of a medium-sized municipality in the interior of São Paulo State, during the years 2009 and 2010.

The educational level of most of the students was out of elementary school, followed by nine who had completed high school and eleven of them who were not attending school at the time of data collection. Family income of most of the participants did not exceed three minimum wages prevailing at the time. Regarding the use of psychotropic substances and narcotics, most participants reported using cigarettes and marijuana. From all the adolescents who made up the sample, 10 were repeat offenders in meeting social and educational measures.

Instruments

a) Adolescents' Identification Questionnaire. The questionnaire is drawn from the literature in order to identify variables that characterize the socio-demographic profile of adolescents and their families.

b) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The SDQ makes it possible to identify problems related to children's mental health. The questionnaire has versions to be answered by the adolescents, their parents and teachers. In this study, the version to be answered by adolescents themselves was used. It consists of 25 items and the sum of the scores makes it possible to identify three levels of mental health: normal, borderline or abnormal (treated in this study as "clinical"). In addition, the items are divided into five sub-scales, identifying mental health levels in the following aspects: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, problems with peers and prosocial behaviour. The scale also presents the impact supplement that evaluates the impairment from the symptoms presented14,15. In cultural validation studies for Brazilian adolescents, the SDQ was considered appropriate for the screening of psychiatric disorders in Brazil15.

c) Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. To evaluate self-esteem, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was used. It was developed in 1989 by Rosenberg and translated into Portuguese and culturally adapted by Avanci et al.16. The total score can range from 10 to 40 and the higher the score, the higher the self-esteem of the respondent. The application of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale generates scores that do not have standardization within the high ranking, normal and low. The instrument guidelines indicate that low scores represent low levels of self-esteem while high scores represent the opposite.

d) Social Support Appraisals for Children and Adolescents (SSA). To evaluate the social support for adolescents, we used the Brazilian version of the Social Support Appraisals for Children and Adolescents, transculturally adapted for Brazil17 The questionnaire was originally developed by Vaux in 1986. The instrument has 30 questions, and the total score reflects the perceived social support. The SSA is divided into four sub-scales: beyond perception of support from others, it assesses the perception of support from family, friends and teachers17. The levels of social support arising from the application of the SSA can be interpreted using its rating: low, normal and high. Originally the scale does not show the ranges of scores that generate each of these results; however, the guidelines for its use indicate the minimum and maximum scores for each subscale and point to the establishment of low ratings, normal and high for each population group studied17.

e) Parental Styles Inventory (PSI). In order to identify the parenting styles adopted by parents of adolescents we used the Parental Styles Inventory. The PSI was developed and validated by Gomide18 indicating subscales of negative parenting practices (practices neglect, physical and psychological abuse, relaxed discipline, inconsistent punishment, negative monitoring) and positive (positive monitoring and moral behavior). The instrument has versions to be answered by the child, father and mother. In this study we used the version to be answered by the adolescents themselves.

Procedures

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), meeting all requirements of Resolution CNE 196/96.

Participants were located at the time of entry onto the social and educational measures programme or when they came to care and routine activities. On these occasions, it was possible to establish contact with teens and their parents, explaining the study and its objectives, and invite them to participate. After agreeing to participate in the research, they signed the informed consent form, and data collection was performed.

Data analysis

The data related to standardized instruments used: Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale, PSI, SDQ and SSA were treated from spreadsheets of each and analysed descriptively.

For the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale analysis, although its application generates scores that do not have regulation, taking into account the guidance of the authors, it indicates that low scores represent low levels of self-esteem while high scores represent the opposite; classification ranges were set to be adopted in this study as follows: score ranging from 10 to 20 = low rate; scores ranging from 21 to 30 = normal rate; and scores ranging from 31 to 40 = high rate.

Although guidelines for carrying out the analysis of the SSA point to establishing ranges for each population studied, we found that the sample of this study was restricted, and it was decided to use the rating ranges established in the study of Squassoni and Matsukura17, where the instrument was culturally adapted to Brazil and applied to a sample of 218 participants.

For statistical analysis of the correlation between the variables, the nonparametric Spearman correlation test was used. It was observed that the results were considered significant when the p-value was less than 0.05, assuming a probability error value of 5%. To carry out the statistical analysis, we used the Statistics Software 7.

RESULTS

Descriptive results of evaluations of mental health levels, self-esteem, parenting styles and social support are presented below. Subsequently, the results of correlation analysis between variables are presented.

Mental health of adolescents

Table 1 shows the results obtained from the responses of adolescents who answered the SDQ.

It was observed that 67% of participants have difficulties related to mental health, scoring as "Clinical" in the total score of the instrument. Yet, it is observed that most of the participants present a "Clinical" score in the following subscales:Conduct Problems; Hyperactivity; Relationship Problems. Regarding Pro-Social Behaviour (the only ability evaluated by the scale) 94% of the participants scored "Healthy".

Self-esteem

Table 2 shows the rates of self-esteem evaluated by the obtained ratings, as adopted in this study.

It can be seen that most adolescents have normal levels of self-esteem and none of them had a high rating, which is the highest score in the evaluation instrument.

Parental Styles

Table 3 shows the evaluation results of adolescents in relation to parental styles adopted by those responsible for them.

It is observed that all adolescents evaluate negatively the parental styles adopted by their responsible adult. The regular styles above average and great were not scored.

Social Support

Table 4 presents the results arising from the application of SSA by the participants, taking as a reference the classification bands adopted in the study by Squassoni and Matsukura17.

It is observed that 42% of the adolescents realize their full social support as low and 42% assessed the social support they receive from family as high. Regarding the perception of support from friends, 36% considered it average. Support arising from teachers and others was rated as normal.

Results for the correlation analysis between the variables mental health, self-esteem, parenting style and social support.

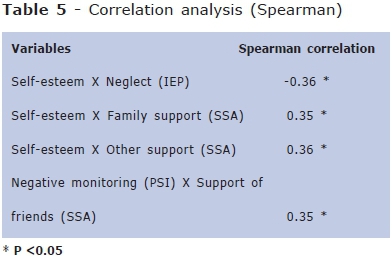

Table 5 shows the correlations between variables of the instruments: SDQ, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, PSI and SSA.

There were no correlations between mental health evaluated by the SDQ and any other variable investigated in this study.

The self-esteem of the adolescents was related to neglectful parenting practice and to the perception of social support received by family and others, so that the higher the perception of the adolescents in relation to these sources of support and the less the responsible adults are negligent, the higher the self-esteem of the adolescents.

Another correlation found refers to the variables negative monitoring parenting style and social support received from friends, so that the more parents use negative monitoring in daily life with children, the more they realize the support of their friends.

DISCUSSION

In this study it was found that the educational level of young people in conflict with the law is low. Considering the average age of participants is approximately 16 years, it would be expected that adolescents have already completed elementary school. However, 39% of the participants have not finished elementary school, while 27% have not completed high school. These results confirm findings of previous studies where the educational level of adolescents in social and educational measures of different types has been identified as low5,19. In addition, 34% of participants do not attend school at all, which points to the urgency of intersectoral actions involving, in advance, an active dialogue where the school and the different sectors may achieve changes in this situation.

This demand is also reinforced by Gallo and Williams, indicating that school attendance is related to the infringement conduct of adolescents, since the number of relapses and the use of drugs by adolescents attending school was smaller than by adolescents who did not attend19.

Regarding the use of other psychotropic substances and narcotics, cigarettes and marijuana were substances that most participants reported consuming. In this direction, considering consumption patterns of legal and illegal drugs specifically among adolescents in conflict with the law, studies show that early drug use predisposes adolescents to engage in violation practices early, suggesting that the use of illicit substances makes them vulnerable to adopting criminal behaviour11,20,21. In addition, there is evidence on the consequences of the use of substances at this stage of development, as noted by Rigoni and co-workers for example, where they found that adolescents who use marijuana may have their neurological functioning affected by drug use, since they have a worst cognitive performance when compared to adolescents who do not use marijuana22.

In the same direction, Heim and Andrade published a review on the effects of drugs and alcohol on the risk behaviour of adolescents. They also found relations between delinquent behaviour and use of illicit drugs and alcohol23.

Regarding the implementation of the socio-educational measures, 30% of the study participants were repeat offenders. Among the hypotheses related to relapse into the offending, one of them has to do with the low effectiveness of social care programmes and the activities proposed in such programmes (type, scope, membership among others) that even being very effective are hardly present in the context of life of the adolescents.

There is no doubt in recognizing the advances made since the implementation of the Child and Adolescent Statute and, specifically, in the case of adolescents and their infringements and socio-educational measures. However, as researchers in this field have shown, it is essential to progress towards the educational character of such measures and, in addition, the effectiveness of it24,25. In this sense, the relationship between services and different policy areas, actual involvement and attention to families and offering strong support to educators appear to be central points of investment for improving the effectiveness of such programmes.

Below, we discuss and compare with the existing literature in the area the descriptive results of the instruments used in data collection, namely: SDQ (the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, SSA (the Social Support Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents) and PSI (the Parenting Styles Inventory).

Regarding conditions of mental health of adolescents in this study, it was found that 67% of participants have difficulties related to mental health, scoring as "Clinical" in the total score of the instrument. These results confirm previous research and reinforce the need for attention and care targeted to this population7-10.

However, in a sphere where, for so long, health status and disease presented standards and norms, it is necessary to (re)contextualize what is meant by care and attention. So, getting back to the mental health interface of these adolescents does not imply returning to the past of links between disease, institutionalization and individualization of problems that this stance still often implies It is not a recipe but, in this view, is therapy-cure-individual intervention; thus, the social/real focus is lost26. Nevertheless, even if this view and its implications are strongly rejected, we cannot take the risk of denying the importance of the sphere of adolescent mental health in general and these young people fulfilling socio-educational measures in particular when dealing with the guarantee of rights and people in process of developing fully.

On the contrary, it requires the consideration that an often threatened development must be protected, providing conditions for facing the issues that arise in the everyday life of each one. Development is promoted from a health perspective, as expressed by Coast and Assisi13. It is the way to guarantee rights. The psychic pain placed on these adolescents is present and must be understood. If disregarded, the chances of development, living and coping decrease. Thus, there is an urgency to pay attention to an issue that is added to others that make up this complex reality and, as such, requires specific actions and policies of attention.

Reinforcing the demand for attention in the sphere of the mental health of these young people, the results of this study revealed that while 67% of participants submit scores on clinical levels, 94% of participants achieved scores that placed them in the "healthy" range of evaluation in the sub-scale of pro-social behaviour (the only ability evaluated by the instrument). This result, in our understanding, reveals that even with evident difficulties (observed by clinical scores), there is huge potential and availability for sharing and building with peers; thus addressing the difficulties should also enable the maximization of expressive skills.

To better understand and carry out measures for the development and the different contexts, this study also sought to investigate risk and protective factors involved in the mental health of adolescents, and, to that extent, self-esteem, social support and parenting styles of their caregivers were considered.

We could observe that most adolescents have normal levels of self-esteem and none had a high rating. In relation to social support, 42% of the adolescents perceive their full social support as low, and 42% evaluated the social support received from family as high.

It is hypothesized that the results of this study, in contrast with the literature, may be related to problems associated with the instruments of measurement and their reliability and the small sample of studies. Further studies evaluating such size with larger samples and other validated instruments can add further contributions to the understanding of results.

With regard to social support perceived by adolescents, although 42% of the adolescents evaluated the overall social support they receive as low, for the family subscale, 42% perceive the support from this source as high. In this direction, the results reinforce the need for care and extending the social support source for this population and reaffirm the family as an important source of support in adolescence.

It was also found that the total social support and the support from family, friends, teachers and others in general was positively correlated with self-esteem, which means that the greater the support received from all sources, the higher the self-esteem levels presented by adolescents. In agreement with the data presented, studies of several authors also indicate that satisfactory levels of social support exert positive influence on the development of optimal levels of self-esteem27-29.

Regarding parental styles adopted, it was found that all adolescents evaluated parental styles adopted by their responsible adult negatively, i.e., a risk for the development of anti-social behaviour in children. In addition, although no relationship has been demonstrated directly with mental health, there was a relationship between parental styles and self-esteem, where the self-esteem of adolescents was related to parenting negligence. The more the parents are negligent, the lower the self-esteem of adolescents.

The results presented reinforce the need for interventions with relatives and guardians. It is necessary to move forward and implement actions that certainly do not intend to hold the State and society harmless but, in contrast, intend to add others involved in this complex context in which the adolescent is. In this sense, social and educational activities must reach the families and also expand to the community, social supports and others present in the daily routine where the adolescent develops.

CONCLUSIONS

Most of the adolescents had mental health disorders and evaluated the social support received as low or medium. All participants evaluated negatively the parental style adopted by their parents. The parental style used was considered below average and risky. Furthermore, was observed that the lower the self-esteem of the adolescents and the lower the family support perceived by them, the higher was the degree of parental negligency evoluated.

REFERENCES

1. Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1985; 147(6):598-611. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.147.6.598 [ Links ]

2. Hutz CS (org.) Situações de risco e vulnerabilidade na infância e na adolescência: aspectos teóricos e estratégias de intervenção. In: Reppold CT, Pacheco J, Bardagi M, Hutz C. Prevenção de problemas de comportamento e desenvolvimento de competências psicossociais em crianças e adolescentes: uma análise das práticas educativas e dos estilos parentais. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. 2002. [ Links ]

3. Sapienza G, Pedromônico MRM. Risco, proteção e resiliência no desenvolvimento da criança e do adolescente. Psicol Estudo. Maringá: 2005; 10(2): 209-16. [ Links ]

4. Gallo AE, Williams LCA. Adolescentes em conflito com a lei: uma revisão dos fatores de risco para a conduta infracional. Psicologia: Teoria Prática. 2005; 7(1): 81-95. [ Links ]

5. Garguilo RM. Special Education in contemporary society: an introduction to exceptionality. Alabama: Thomson Learning; 2003. [ Links ]

6. Priuli RMA, Moraes MS. Adolescentes em conflito com a lei. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2007; Rio de Janeiro: 12(5): 1185-92. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232007000500015 [ Links ]

7. Karnik NS, Soller M, Redlich A, Silverman M, Kraemer HC, Haapanen R, et al. Prevalence of and gender differences in psychiatric disorders among juvenile delinquents incarcerated for nine months. Psychiatr Serv. 2009; 60(6): 838-41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.60.6.838 [ Links ]

8. Oliván GG. Delinquent adolescents: health problems and health care guidelines for juvenile correctional facilities. An Esp Pediatr. 2002; 57(4): 345-53. [ Links ]

9. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arc General Psychiatry. 2002;59(12): 1133-43. [ Links ]

10. Andrade RC, Assumpção Junior F, Teixeira IA, Fonseca VAS. Prevalência de transtornos psiquiátricos em jovens infratores na cidade do Rio de Janeiro (RJ, Brasil): estudo de gênero e relação com a gravidade do delito. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. Rio de Janeiro: 2008; 16(4): 2179-88. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000400017 [ Links ]

11. Silva MDFDT, Farias MA, Silvares EFM, Arantes MC. Adversidade familiar e problemas comportamentais entre adolescentes infratores e não infratores. Psicol Estudo. 2008; 13(4): 791-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722008000400017 [ Links ]

12. Pinho SR, Dunningham W, Aguiar WM, Andrade AS, Guimarães K, Guimarães K, et al. Morbidade psiquiátrica entre adolescentes em conflito com a lei. J Bras Psiquiatr. Rio de Janeiro: 2006; 55(2): 126-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0047-20852006000200006 [ Links ]

13. Costa CRBSF, Assis GS. Fatores protetivos a adolescentes em conflito com a lei no contexto socieducativo. Psicol Soc. Porto Alegre: 2006; 18(3):74-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822006000300011 [ Links ]

14. Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997; 38(5): 581-6. [ Links ]

15. Fleitlich B, Goodman R. Social factors associated with child mental health problems in Brazil: cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2001; 323(7313): 599-600. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7313.599 [ Links ]

16. Avanci JQ, Assis SG, Santos NC, Oliveira RVC. Adaptação transcultural de escala de auto-estima para adolescentes. Psicol Reflex Crít. 2007; 20(3): 397-405. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722007000300007 [ Links ]

17. Squassoni CE, Matsukura TS. Adaptação Trans-cultural da versão portuguesa do Social Support Appraisals para o Brasil. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2014; 27(1): 71-80. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722014000100009 [ Links ]

18. Gomide PIC. Inventário de estilos parentais: modelo teórico, manual de aplicação, apuração e interpretação. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes; 2006. [ Links ]

19. Gallo AE, Williams LCA. A escola como fator de proteção à conduta infracional de adolescentes. Cad Pesqui. 2008; 38(133): 41-59. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-1574200 8000100003 [ Links ]

20. Farrell AD, Sullivan TN, Esposito LE, Meyer AL, Valois RF. A latent growth curve analysis of the structure of aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors and their interrelations over time in urban and rural adolescent. J Res Adolesc. 2005; 15(2): 179-204. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00091.x [ Links ]

21. Gatti U, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, McDuff P. Youth gang, delinquency and drug use: a test of the selection, facilitation, and enhancement hypotheses. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005; 46(11): 1178-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00423.x [ Links ]

22. Rigoni MS, Oliveira MS, Moraes JFD, Zambom LF. O consumo de maconha na adolescência e as conseqüências nas funções cognitivas. Psicol Estudo. 2007; 12(2): 267-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722007000200007 [ Links ]

23. Heim J, Andrade AG. Efeitos do uso do álcool e das drogas ilícitas no comportamento de adolescentes de risco: uma revisão das publicações científicas entre 1997 e 2007. Rev Psiq Clín. 2008; 35 (Supl.1): 61-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.159 0/S0101-60832008000700013 [ Links ]

24. Francischini R, Campos HR. Adolescente em conflito com a lei e medidas socioeducativas: limites e (im)possibilidades. Psico. 2005; 36(3): 267-73. [ Links ]

25. Bazílio LC, Kramer S. Infância, educação e direitos humanos. São Paulo: Cortez; 2003. [ Links ]

26. Cruz L, Hillesheim B, Guareschi NMF. Infância e políticas públicas: um olhar sobre as práticas psi. Psicol.Soc. 2005; 17(3): 42-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822005000300006 [ Links ]

27. Demaray MK, Malecki CK, Davidson LM, Hodgson KK, Rebus PJ. The relationship between social support and student adjustment: a longitudinal analysis. Psychol Schools. 2005; 42(7): 691-706. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pits.20120 [ Links ]

28. Harter S, Waters PL, Whitesell NR. Relational self-worth: differences in perceived worth as a person across interpersonal contexts among adolescents. Child Dev. 1998; 69(3): 756-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1132202 [ Links ]

29. Antunes C, Fontaine AM. A relação entre o conceito de si próprio e percepção de apoio social na adolescência. Cad Consulta Psicol. Porto: 1996; 12: 81-92. [ Links ]

Corresponding author: thelma@ufscar.brthelma@ufscar.br