Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

Print version ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. vol.41 no.1 Porto Alegre Apr. 2007

ENFRENTANDO A LOS OTROS: ESTIGMA EN EL SECTOR SALUD

HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination among nurses in Suriname

Estigma y discriminación por VIH/SIDA en el personal de enfermería en Surinam

Dermatology, Ministry of Health, Suriname

ABSTRACT

The more civilized a society becomes the more subtle the stigma and discrimination gets. Suriname is a country known for its folklore, hospitality, and social control. In the last decennia a new trend of cultural diffusion has led to greater recognition of formerly classed deviant practices of behavior. Under the influence of this kind of exposure our norms, values, and beliefs now cater for modern day perspectives of liberal thinking that encompass acceptance of one another on the basis of perceived differences of culture and appearance. Yet still, stigma and discrimination play a part in our day to day experiences of religion, poverty, independence, freedom of choice, social strata, disease prevention and even political ferment.

Keywords: HIV, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, Stigma, Discrimination, Nursing, Suriname.

RESUMEN

Mientras más civilizada viene a ser una sociedad el estigma y la discriminación se hacen más sutiles. Surinam es un país conocido por su folklore, hospitalidad y el control social. En el pasado decenio la nueva tendencia de difusión cultural ha llevado al reconocimiento de conductas previamente consideradas como prácticas desviadas. Bajo la influencia de ese tipo de exposición nuestras normas, valores y creencias se encaminan hacia perspectivas modernas de pensamiento liberal que conlleva la aceptación mutual en el contexto de las diferencias percibidas de apariencia y cultura. Sin embargo el estigma y la discriminación juegan una parte en nuestra experiencia cotidiana de la religión, la pobreza, la independencia, libertad de selección, estrato social, la prevención de enfermedades y hasta el fermento político.

Palabras clave: VIH, Síndrome de Inmunodeficiencia Adquirida, Estigma, Discriminación, Enfermería, Surinam.

It is remarkable to see the dynamics of cultural diversity in a country with such closely knitted ethnic societies blend into one people that have a sense of patriotism and a prevailing hope for stability and peaceful progress. Suriname's current incidences of stigma and discrimination are resolved in a cautious, but peaceful manner. Explanation for this phenomenon can be traced back to the development of our perspectives of survival and contentment and an even laid back attitude which we sometimes demonstrate.

Defining Stigma and Discrimination

To some, stigma and discrimination is demarcated by the measurement of its opposite in our existence. Others see it as a mere notion of suppressed ego and unfulfilled maturation into adulthood. Even more common is the understanding that these two unpleasant attributes go together hand in hand. Therefore one does not talk about stigma without mentioning discrimination. There are those that have even developed a sequence for their occurrence by stating that people first stigmatize and then discriminate.

The Encarta dictionary employs the following definition for discrimination:

"Discrimination, any situation in which a group or individual is treated differently based on something other than individual reason, usually their membership in a socially distinct group or category. Such categories would include ethnicity, sex, religion, age, or disability. Discrimination can be viewed as favorable or unfavorable, depending on whether a person receives favors or opportunities, or is denied them… However, in modern usage, "discrimination" is usually considered unfavorable". (Microsoft® Encarta® Encyclopedia 2000)

Martin Luther King Jr. once said that we fear that which we do not know. If this is true then the unknown may not only become the object of our interest, but also the goal of our intellectual curiosity in our efforts to alleviate our fears. More so, we may start calculating our fears on the basis of that which we do not know. If this is the yardstick of our conviction then our problem is made worse, since it is only by confrontation that we realize that which we do not know.

The problem with stigma and discrimination is that it is often a derivative of our instinct to live and protect life. Our tendency to survive has made us filter out the dangers that can cause us not to survive. Sadly enough, this sort of instinctive behavior leads us to stigmatize and discriminate against those that we perceive as causing danger to our existence. In the case of HIV/AIDS this tendency is prolonged because of the fact that we know the detriment resulting from this disease and the shame and taboo that surrounds it in our small Caribbean States where social control prevails.

Stigma and discrimination are often seen as deriving from a lack of knowledge and understanding of a person, situation, characteristic, personality trait and even emotion. In doing so it is often dismissed as a subtle sense of bias, which can be dispelled as soon as more information is made available to us about the given person or situation. This may be the reason why so many HIV/AIDS advocacy programs focus on information sharing tactics, while hoping that prevention and acceptance are wrought through one singular effort of advocating the do's and don'ts of sexual exploits and habitual living traits.

Since the eighties we have come to realize that stigma and discrimination for HIV/AIDS is as cunning as the mutation of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus and often leaves us with a sense of helplessness, anger, and frustration when we encounter it. The progression of AIDS as a medical disease is similar to the havoc caused by societal stigma and discrimination of HIV and AIDS.

Background on Suriname

Historic, Geographic and Demographic Characteristics of Suriname

Suriname is a country situated at the northern coast of South America. It is surrounded by French Guyana in the East, Guyana in the West, Brazil in the South and the Atlantic Ocean in the North. The country is a former Dutch colony, but gained independence in 1975 after approximately 300 years of Dutch dominion. Since the abolition of slavery in 1863 a series of indentureships occurred which brought together people from India, China, Java and Indonesia into one conglomerate culture that existed among descendants of African slaves (primarily from the west coast of Africa), descendants of former colonizers and plantation owners (primarily Dutch), and indigenous Amerindian tribes (mainly Arowaks and Caribs). Due to the geographical size of the country (162,000m2), it was still then possible to keep ethnic groups separated.

Initially the separation was a result of the fact that in most mainland territories of the Caribbean, colonizers and conquistadors only settled in the coastal areas were trade of humans and goods was taking place. Later the separation was used as a tactic to keep the various ethnic groups and or politically strategic groups segregated from one another. This form of dominance has been called Divide and Rule politics (Caprino, 1995) which dates back to separate peace talks, which were held with tribes of maroons (Aucaners, Aloekoes en Saramaccaners the tree different tribes of maroons) in the 1760's. The term maroon was coined as a group of slaves that had fled from plantations during slavery. Because of the activities such as rebellion and plundering of plantations, the government deemed it necessary to sign peace treaties with them. These peace treaties were set with such cunning and distinctive terms that the then existing white population kept dominion of all others. Though the population ratio of Negro to Caucasian in Suriname was 20:1 at that time, the treaties signed and tactics used by the Dutch governing colonizers prohibited fraternization among various groups of maroons and slaves. Two of the tenets of the peace treaties signed in 1760 and 1762 between the Dutch colonizing government and the Aucaners (1760) and then the Saramaccaners (1762), specifically stated that:

The maroons would not go to town or the plantation without permission. The maroons would not take new runaway slaves in their tribes, but they should return the runaways for which they would get a reward. (Caprino, 1995, p. 119)

Ironically enough maroon tribes were formed by runaway slaves from plantations. Forcing this limitation on the maroons, as part of peace talks, meant forcing them to limit themselves and fellow slaves in their quest for freedom and existence. The incentive created in this regard was one of the known tactics used to prevent cultural diffusion and geared towards ethnocentric tendencies among those that were in maroon tribes and those that wished to join. This was one of the institutionalized mechanisms that perpetuated and in some cases harnessed an instilled notion of superiority among people of similar origin, language, culture and even physical distinctions in Suriname.

Geopolitical Transitions Since 1975

On February 25, 1980 Suriname experienced a military coup. Many say that this type of insurgence was the result of discontentment among a group of sixteen militaries led by Desi Bouterse. The fact is that for the first time in our history we experienced such a takeover of government by citizens of the country registered in the armed forces. As a result of this coup there were changes made to the political structure and hierarchy of power in the country. The military appointed leaders for the country and the existing climate of democracy and freedom of expression was censored (Hoogbergen & Kruijt, 2004). There were no elections until 1987 and the main form of government was more autocratic than democratic. Insurgence was dealt with in a military way.

In 1986, there was a guerrilla upheaval led by Ronnie Brunswijk. Mr. Brunswijk was an ex-military commando who gathered together a group of fellow maroon descendents to fight against the protective armed forces of the country. Due to this guerilla war, blood of innocent people was shed and great numbers of persons migrated from Albina, Moengo and other villages in the East in addition to migration from the district Brokopondo and Sipaliwini to Paramaribo, the capital of Suriname. One of the major demographic results of this migration was the increase of maroon descendents in neighborhoods such as Latour, Abbra Broki and Wintie Wai. Since the infrastructure of these urban outskirts of Paramaribo did not cater for such a sudden increase of population, living conditions in these areas became hazardous and led to newly formed villages such as Sunny Point. In instances such as the case with Sunny Point, housing development areas of the government were cracked by squatters in search of a place to stay.

Sociological Background of Stigma and Discrimination in Suriname

Suriname is not unknown to the gruesome practices of slavery. For more than three hundred years we have been a colony in transition to a society of neo-colonial influence. Due to different colonizers we have been left with a folklore that reveals a spectrum of various cultures of the world. The most common of languages is Taki - Taki (Sranan Tongo) and has a blend of dialects traced back to the west coast of Africa, with a mixture of Dutch, Spanish and English. This blend is the result of the need of colonizers to communicate with their slaves. Along with the urge to communicate, there was also an urge to segregate, since the dominant culture of the colonizers was only practiced by whites, who were far less in numbers than the slaves.

In some cases the segregation was voluntary, since slaves chose to flee from the plantations to the jungle in search of freedom. Tribes that were formed in this manner were called "maroon tribes" and were primarily found in Suriname and Jamaica (the vast geographical landscape and geographical relief of both territories afforded the slave a chance to run away). The word "maroon", however, is a derivative of the word Cimarones, which loosely translated means runaway animal. Similarly in our lengua franca, a strong connotation existed for the word marron. The word marron, (Cinmarones) did not just signify a slave that had runaway and was out of bondage, but more so the fact that by calling a slave a marron, runaways were seen as runaway animals. And these "animals" had to be persecuted; punished or mutilated to instill fear in others that had similar intentions.

Society, Sex and Sexuality

In Suriname, just like lots of other parts of the Caribbean, an open discussion on sex, sexuality, and sexual preferences has not yet become part of street corner conversations. There is an inclination towards secrecy and taboo when matters concerning sex are discussed and it is believed that in some subcultures of the country love making and sex education are not seen as part of childrearing.

There is a change of sexual acceptance and openness of sexual expression that has taken place in the last 15 years. What was termed as rudeness and disgusting has now found a place in class discussion and television programs in Suriname. There is an even greater structural change taking place that marks the beginning of a free flow of information on sex and sexuality in our educational system, which is monitored and orchestrated by the Basic Life Skills Program (local counterpart of Health Facts for Live Education).

HIV/AIDS Statistics for Suriname

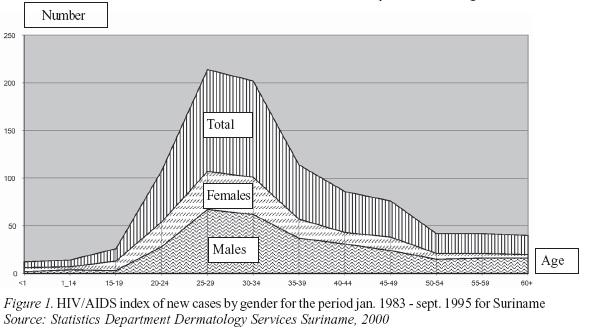

The first reported case of HIV/AIDS in Suriname dates back to 1983 (Prohealth, 2004). As a result of the then newly discovered disease a National AIDS Commission was created in 1986. This commission consisted of medical doctors which were working in the field of HIV/AIDS. In 1988, the Ministry of Health created the National STI/HIV/AIDS Program. The main purpose of this program was to reduce the spread of HIV/AIDS in Suriname and to work as the executing arm of programs that would mitigate the spread and impact of HIV/AIDS in Suriname. Since HIV/AIDS is known to have a geometric progression, its prevalence increased over the years as seen in Figure 1.

Just like all other countries of the Caribbean, the progression of HIV is most prevalent in the age group 15 - 49. This occurrence is generally associated with the age of the people in the labor force of a country and as such gives evidence why the effects of HIV/AIDS are correlated to productivity. On a macro economic scale HIV/AIDS affects the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of countries in the Caribbean. Reports of UNICEF indicate that with the current progression of HIV/AIDS in the Caribbean, there will be a decline of GDP by the year 2010 (Senaapa, 2002). Even more startling is the fact that the ages between 15 and 49 are also considered to be the years of sexual reproductivity. Current trends of test results of HIV/AIDS at the Dermatology Department at the Ministry of Health reveal 2082 HIV cases from 2000-2005.

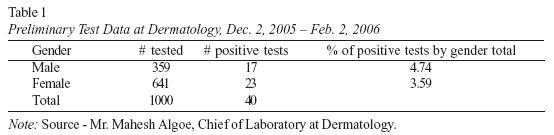

Since November 2005 there has been a "know your status campaign" that encourages people to get tested voluntarily in conjunction with safer sexual practices and availability of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART). This campaign has resulted in a number of test sites being erected throughout the country. A preliminary analysis of sample data from Dermatology, one of the major test sites is shown in Table 1.

Though this rudimentary data still has to be scrutinized and placed in macro statistical context, it confirms suspicion that prevalence ratios in Suriname may be higher than indicated by reported cases of HIV/AIDS, such as confirmed in the Situation and Response Analysis on HIV/AIDS Report (Prohealth, 2002)

Incidences of Stigma and Discrimination

Recorded Stigma and Discrimination

De Ware Tijd, one of Suriname's local newspaper reports the following incident of stigma and discrimination:

this is not how you should die? This can also happen to me said Randjiet Dewnarain, a friend that accompanied 29 year old AIDS patient Pran Mahadew, to Acamdemisch Hospital Paramaribo (Local Hospital). Mahadew died yesterday afternoon in the Office of Maxi Linder due to an infection of the lungs. He was refused treatment at the Emergency Medical Facilities of the Academisch Hospital Paramaribo. (Aviankoi & Irion, 2006, p. 1)

The article continues by pointing out that one of the residing physicians of the Emergency Room at Academisch Hospital blatantly indicated that Pran Mahadew would not be treated because he was an AIDS patient and that he should be sent to St. Maxi Linder, an HIV/AIDS non governmental organization, specializing in Street Based Commercial Sex Workers. Pran was almost thirty and had been HIV positive for ten years. He was a street commercial sex worker and did not have a social security card. His mother says that they were in the process of getting one as the incident occurred. He was referred to the hospital by a general physician that saw the seriousness of his illness. An attending nurse, who did not wish his identity to be known, said that Pran was not refused treatment. "We took a photo of his Lungs and did not see any need to keep him in the hospital" (Aviankoi & Irion, 2006, p. 4).

This incident did not only shock me, but my colleagues as well. It is not the first, but the most recent of account that I have heard regarding the treatment of people living with AIDS (PLWA) in hospitals. I should rush to say that not all accounts show discriminative treatment of PLWA, but we hope to bring these startling accounts to minimal and scarce occurrence.

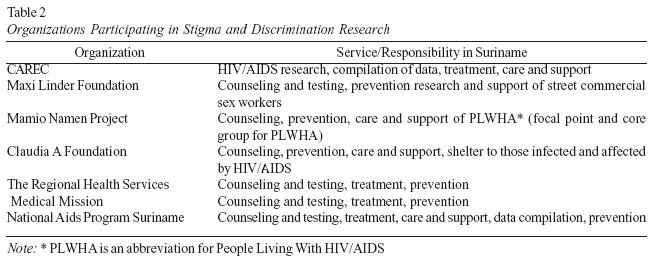

Reports of Stigma and Discrimination among Healthcare Workers

In Suriname a fairly reasonable amount of research has been done on HIV/AIDS. What is evident, however, is the fact that this research does not particularly address HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination. In recent years researchers have acknowledged this gap and have endeavored to focus on the so called "softer" side of science when doing research on HIV/AIDS. Two important investigations were done to cover possible existence and/or the nature of HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination in Suriname in the past two years. The first was done by a Working Group on the Reduction of Stigma and Discrimination (2004) and the second was done by me in 2005 and completed in 2006. The Working Group on Stigma and Discrimination consisted of representation of CAREC/PAHO, Maxi Linder Foundation, Mamio Namen Project, Claudia A Foundation, The Regional Health Services, The Medical Mission, and the National STI/HIV/AIDS Program Suriname. I was fortunate enough to represent the National STI/HIV/AIDS Program Suriname in this group of researchers. All of the mentioned organizations work with HIV/AIDS and as such have specialized task and responsibilities in the execution of their services. The specific responsibilities from these organizations are listed in Table 2.

There are countries that place Counseling and Testing under Prevention, but I choose to list it particularly in this Table 2 since it is the crosscutting service that all these agencies provide. The research that resulted from this joint venture of agencies was geared towards the detection of HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination among health care workers by focusing on PLHWA.

In my research on stigma and discrimination (2005/2006) I also focused on student nurses and qualified nurses working in hospitals, clinics and private institutions. My focus was distinct in the sense that it used a deductive approach of behavior traits and attitude to determine the modus operandi from those nurses working in hospitals and clinics and private institutions, while being part of a wider society. As such there were four distinct sub-categories in my research, revealing:

- Personal data: Identification to prevent duplication in my investigation.

- Knowledge data: Area that showed familiarity with HIV/AIDS.

- Attitude data: Area showing their beliefs and thoughts with regards to HIV/AIDS.

- Personal and social health beliefs: Area giving possible motivation of such beliefs and thoughts by personalizing HIV/AIDS in their family relations.

Research Methodology and Background

This research was carried out among nursing students and qualified nurses studying at COVAB Foundation. The COVAB Foundation is one of two primary agencies responsible for the preparation of student nurses to become nurses. In addition to these services, it also trains nursing assistants and tailors special training courses for qualified professional nurses. The institution has both fulltime and part time lecturers and provides students with housing facilities. Over a period of four years, student nurses receive both theoretical and practical training as will be shown in the results. In the test phase of the survey a group of thirty (30) final year nursing students were used as a pilot group to establish accuracy of logic and scope of the survey. After participation, I carefully mapped out the methodology used to acquire data through this survey after which I divided the students in three groups of ten (10) students. As a pilot group, they were asked to comment on logic flow, accuracy, relevance and difficulty levels of the questions from the survey. Ninety percent (90%) of these pilot participants indicated that the approach used was fresh and dynamic and some of them even wanted to use the research scheme as an example for their final research report. From the 10% that remained, one pilot participant was undecided and two reiterated the fact that such a survey should not be done among first year nursing students, since they may not have enough nursing experience to back up their perspectives. Afterwards, these pilot participants were to become field assistants in the sense that they had to carry out the research in the other selected populations.

The survey was to be carried out concurrently in three selected groups in a class setting, thus preventing participants from discussing survey questions with one another. This was done in an attempt to let each participant give his/her own, unbridled, uninfluenced and unchallenged opinion of the questions asked. The remaining group was surveyed immediately after in a different section of the compound. Each group was given an organizational division with specific responsibilities given to each group member. This aided in accurate execution of the survey.

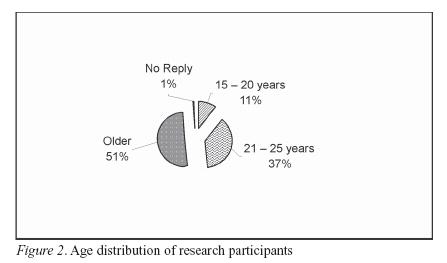

A total of five (5) groups of nurses were sampled, namely: one (1) group of registered nurses in training to become diabetic nurses, three (3) groups of third year nursing students and one (1) group of nurses in their final year. The total number of participants was 112. The total number of survey forms returned was 112. Two (2) of the forms had double answers and had to be discarded. The remaining 110 returned forms were considered as the total number of participants (n). The survey was carried out in the third week of January, 2006. Survey data shows that 14% of participants were males and 86% females.

The participants in this research were not selected because of gender distinctions. The groups of nurses were selected on the basis of the year group that they were in and the class that they attended at the time the survey was conducted. Male/female division of this survey is also representative of the gender ratio of nurses in Suriname. Although the division is not a numeric or direct representation of the ratio male/female, it is reflective of the fact that there are more female than male nurses in Suriname. The age of the participants can be seen in Figure 2.

The majority of the nurses in this survey were older than 25 years. Considering the fact that only 17.27% of participants were qualified nurses and they were all over the age of twenty five, it is evident that the remaining 31.73% of nurses over the age of twenty five were still in training. Furthermore, the basic assumption that can be drawn is that the majority of the participants have reached an age of maturity in addition to having acquired life and academic experience that should enable them to form opinions on issues surrounding HIV/AIDS in Suriname.

The assumption can be confirmed when analyzing the results of the question on work experience in the hospital. Almost 45% of the nurses had close to 4 years of experience working in the hospital, followed by 23.6% who had more than six (6) years of experience working in the hospital. The reason why so many nurses had around four and more than six years work experience is because a number of them had already completed the nursing assistant program and had worked in hospitals and clinics. The nursing degree is an additional degree that they were pursuing, but they already had experience working in hospital wards.

Participants' Proximity with HIV/AIDS

The majority of the participants (95.45%) came from hospitals and had direct contact with people living with HIV/AIDS. This placed them in a vocational setting with potential direct physical contact with HIV/AIDS. Those excluded from this category had other means of contact with HIV/AIDS. Contact points were measured in various degrees in an attempt to understand how HIV/AIDS evolved in and around the lives of the participants. There were several stations at which this form of contact was probed. The first was the question: "Do you know someone with HIV/AIDS?". Results to this response demonstrated that 82% knew someone, and 96% had taken care of someone living with HIV/AIDS.

Intrinsic to this question is the notion that HIV/AIDS can only be detected through testing. Knowing the status of a patient means knowing their test result. In the case of taking care of people living with HIV/AIDS in a hospital, of whom knowledge is available on their status, it simply means that they were tested and the information on their status was shared among nursing professionals. This deduction is confirmed when 70% of participants reported that they have told a colleague at work that a patient is HIV positive.

This statement shows that the majority of nurses participating in this research had passed information about patients' positive HIV status. This result made me think whether this is a means of caring and protection of others or whether this is a stigmatization process by which PLWA are identified and his or her health condition is shared without authorization among healthcare workers. This sharing of information seemed to be prevalent among colleagues. Closely related to this deduction is the fact that 47.27% of the participants had received HIV/AIDS training. As HIV training provides better management of the disease, it gives way to the fact that training has provided tools on prevention and that the general training of nurses incorporates disease prevention tactics and measurements of general and specific hygiene as indicated in an interview with Ms. M. Vreugd, Coordinator of the Nursing Program at COVAB (Vreugd, 2006; personal communication). So, there is no need to know the specific sero-status of a patient as long as universal precautions are implemented.

Attitudes and Family Health Beliefs

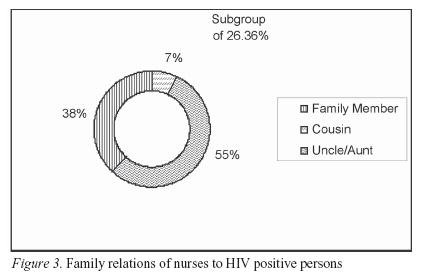

In this section questions focused on blood relations and situation at home. 26% of the participants reported having had an HIV positive family member. The percentage of participants with a relative that was HIV positive was further specified by type of blood relation. It appears that from the group of participants that had a relative which was HIV positive, 55% had a cousin and 38% an uncle or aunt, as presented in Figure 3.

What was also striking about this particular subgroup is that only four had actually lived in the same house with someone that was HIV positive. When asked if they knew how the person got infected, 15.45% from the total participants responded affirmatively. When asked if they passed this information to others only 8.18% did, while 62.73% did not reply to this question. It appears that unlike the situation that exists in the hospital, nurses in this study are not likely to pass information on the positive HIV status of relatives, whether they live in the same household or not.

The question on sharing the same household with someone that is HIV positive tried to establish whether immediate contact with such a person might have changed the attitude towards those infected. From current information it is somewhat difficult to interpolate, whether nurses would pass on information of the status of HIV positive relatives to their colleagues at the hospital, once these relatives are admitted to their hospital. A strong tendency of care and compassion for those infected with HIV/AIDS seems to emerge from the results of the remaining questions of the survey. When asked if people that are HIV positive had to be taken care of in a special way in the hospital, 49.10% said yes, while 45.45% said no and the remaining 5.45% did not know. Drawing from earlier answers it can be concluded that even though 47.27% of the participants had specific training in HIV/AIDS, combined with the information they had of HIV/AIDS as confirmed by interview with Ms. Vreugd, there still existed a sense of singling out HIV/AIDS from other diseases in the hospital.

I do not think that this notion is a direct result of the virulence of the Human Immune deficiency Virus, since there are other diseases with similar if not more aggressive forms of physical, physiological and mental regression. I believe that this type of uncertainty indicates that the fear instilled by HIV/AIDS as a disease can only be mitigated if nurses convince themselves that though exposed to HIV/AIDS at there work place they will not be infected. They are surrounded by information and it seems the trend is not due to a lack of information, but to other obstacles that prevent this information from maturing to practice.

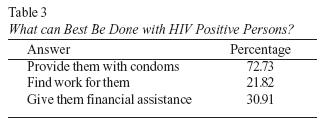

In the last part of the survey the focus was given to opinion formulation regarding people living with HIV/AIDS. Two main questions were asked to establish a perspective on infected persons. The first was "What can best be done with HIV positive persons?" and the results are presented in Table 3.

The main mode of transmission of HIV in Suriname is through heterosexual contact. Given these findings, it seems participants acknowledge that even though transmission might have occurred through sexual contact, the fact that people have become positive should not prevent them from having intercourse. It might also explain the liberal thinking that exists among participants on the right for a person to have intercourse, but more so the right for HIV infected persons to enjoy intercourse and still be responsible enough to protect themselves and others. Nurses recognizing patients' right to a healthy sexual life might be confronted with their own interest in protecting public health as they might believe that PLWA are responsible for the current spread of the infection.

A second conclusion from these results is that there is some agreement in the perception that HIV infected persons may be in a precarious financial situation due to loss of work and/or financial resources. This is the reason why more than 50% of the participants saw a relation between a positive HIV status and lack of financial resources. Furthermore, the subcategory of participants that stated that we need to find work for positive persons, also acknowledged that these persons were fit for work. In a broader sense it shows that even if positive persons do not have jobs, we should not only help them find one but also find no reason to prevent them from working.

From the perspective of economic deprivation due to HIV we end up with a view of family relation that indicates that nurses as parents have two things that stand out when their child comes home stating that he/she has contracted HIV. Most participants (81.82%) indicated that they thought that they would have to find a solution if their child told them that they had contracted HIV. Subsequently 64% of the participants indicated that they thought that their child did not listen to them. Those that indicated that they would look for a solution may regard HIV as a problem which can be solved. It can also indicate acceptance of HIV, which to me seems a rather levelheaded approach to a hypothetical situation.

Conclusion

From historic and present day appearances it seems like Suriname has been blessed with a people that don't strive for vengeance but rather try to accept and adhere to culture, beliefs, norms and values of their fellowmen. In the case of HIV/AIDS, people living with HIV/AIDS may be at risk of having their status revealed to others by those they trusted because of their professional code of conduct. There is no excuse for such attitudes and behavior, but we try to understand such practices by focusing on the fact that HIV/AIDS may still be impersonal and distant to some of us.

Finger pointing and name calling are some of the effects wrought by a breach of confidence and trust once someone's status has been revealed. This does not foster the atmosphere for those living with the disease to have a fulfilling live. It also does not give them the chance to cope with their own struggles, but rather adds to the pangs caused by social and emotional deprivation.

References

Aviankoi, E., & Irion, L. (2006, March 6). We do not treat AIDS patients. De ware Tijd, Accessed on March 6th, 2006 at http://www.dwtonline.com/website/home.asp?menuid=2 [ Links ]

Caprino, M. H. (1995). Contacten tussen Stad en Distric. In Ch. van Binnendjk & P. Faber (Eds.), Cultuur in Surinam (pp. 10-15). Paramaribo, Suriname: Vaco n.v., Uitgevesmaatschappij. [ Links ]

Dermatology Services. (2005). Annual Statistical Reports on HIV/AID 2000 - 2005.

Paramaribo, Suriname: Statistical Department Dermatology Services.

Hoogbergen, W., & Kruijt, D. (2004). Gold, Garimpeiros and Maroons: Brazilian migrants and ethnic relationship in post-war Surinam. Caribbean Studies, 32(2), 3-44. [ Links ]

Microsoft® Encarta® Encyclopedia 2000. (©1993-1999). Discrimination. USA: Microsoft Corporation. [ Links ]

Prohealth. (2002). Situation and response analysis of HIV/AIDS in Suriname (SARA).

Paramaribo, Suriname: Author.

Prohealth. (2004). National strategic plan HIV/AIDS for Suriname 2004 - 2008. Paramaribo, Suriname: Author. [ Links ]

Senaapa, M. (2002). Presentation of UNICEF Figures and Statistics. Paramaribo, Suriname: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Vreugd, M. (2006, February). Interview on curriculum contents of the Nursing Program at COVAB. Paramaribo, Suriname. Personal communication. [ Links ]

Winston Roseval (Suriname) is currently project manager at Dermatology of the Ministry of Health in Suriname. He has been employed by the government in several capacities including lecturer, member of the National Health Information System Team, member of the Sexual Reproductive Health Team, and Coordinator of the National STI/HIV/AIDS program. His research interests include health and social issues regarding the development of adolescents and women. E-mail: winrose@cq-link.sr

1 Address: winrose@cq-link.sr, wroseval@yahoo.com

2 Former Coordinator of the National STI/HIV/AIDS Program in Suriname. He is currently the Project Manager and Advocacy Advisor for Dermatology at Suriname's Ministry of Health.