Services on Demand

article

Indicators

Share

Journal of Human Growth and Development

Print version ISSN 0104-1282

Rev. bras. crescimento desenvolv. hum. vol.23 no.1 São Paulo 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The influence of television on the eating habits of brazilian northeast children

Sophia Motta-Gallo; Paulo Gallo; Angela Cuenca

Department of Maternal and Child Health, School of Public Health, University of São Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: the aim is to assess caregivers' perceptions about the influence of television on the eating habits of children from the socially vulnerable Northeast region of Brazil.

METHODS: a total of 14 semi-structured interviews were conducted with caregivers. The participants included parents and grandmothers of 29 schoolchildren from a public school on the outskirts of a town in the Agreste Meridional in Northeast Brazil. The interviews were transcribed and analysed in the light of socio-historical theory based on the work of Vygotsky (1984) and Bakhtin (2001).

RESULTS: the caregivers explained the influence of televised food advertisements on children's requests for food and the criteria children use to choose foods. The caregivers also observed that the family's buying decisions were governed by the children's requests, which are driven by television advertisements. Furthermore, the children's food preferences (i.e., the structure and rhythm of children's meals) have changed because of the influence of the media.

CONCLUSIONS: although caregivers are able to describe the influence of television on the eating habits of children, the magnitude of this influence on children's lives is still unclear. Understanding the magnitude of the this influence is the challenge posed by this study to professionals, experts in the field, and the Brazilian health system.

Key words: public health; children; eating behaviour; consumer habits; television; qualitative.

INTRODUCTION

From birth, children's eating habits are influenced by factors outside the family environment. Studies have investigated eating as a behaviour that is influenced by food advertisements1, 2.

Despite the economic and sociocultural inequalities in the Brazilian population, globalisation has created universal access to the media which technological advances have enabled socially vulnerable even populations to access. The influence of the media has thus transformed the material conditions of life by people's habits.

Giddens 3 names this phenomenon reflexivity. Castells 4 calls universal media access the culture of real virtuality. In this scenario, collective intelligence, a term coined by Levy5, has become a consensus, with the media acting as the invisible thread that intertwines consciousness, space, questions, and wishes6.

In this context, television is a communication tool. Television is the most affordable vehicle for delivering information to the Brazilian population, given its coverage: ... "reaching a total of 5,565 municipalities and 95.1% of households, television is the main link between the public and the world, having an immeasurable impact on Brazilian society"7.

Thus, there is a need for studies that seek to understand the influence of television on eating behaviours and the eating habits of Brazilian children. This study was designed to determine caregivers' perceptions of the influence of television on the eating habits of Brazilian children.

METHODS

For this descriptive qualitative study, we conducted interviews with caregivers of school-age children from the suburbs of the municipality of Garanhuns in the State of Pernambuco in the Agreste Meridional region of northeastern Brazil.

RESEARCH CONTEXT

Pernambuco is a state in Brazil that consists of 185 municipalities and is divided into macro-regions with specific geopolitical and cultural traits. The state's semiarid climate creates a diversity of shapes and colours among the residents of this region8.

The Agreste Meridional is considered a socially vulnerable region9. The Human Development Index (HDI) of Brazil is 0.718, but the HDI of Pernambuco is 0.652. For reference, Norway had the highest HDI in 2011 (0.943); Brazil ranked 73rd among 169 countries10.

Garanhuns, the regional seat of the Agreste Meridional, is known as the Brazilian Switzerland for the following characteristics: a) climate (ranging from 18° - 5°) and b) topography (a semi-arid city located between seven hills at 1.030 m altitude). Garanhuns is notable for being the largest milk collection centre in the state, accounting for 70% of Pernambuco's local dairy production and serving as the site of the most important dairy operations in Brazil10.

However, there are also areas of extreme poverty in the outskirts of the town. These areas have black ditches, open sewers, and houses without access to treated water coexisting with subsistence farming, differentiating this region from the coastal and metropolitan areas where the residents plant such crops as beans, corn, and cassava10.

Although this region is the most prosperous region of the Agreste, it is also characterised by extreme poverty; for this reason, this region was chosen for this study.

Participants

A total of 14 caregivers (mothers, fathers, and grandparents) participated in this research, representing a subsample of caregivers with more than one child (7-9 years old). These participants were selected in a random drawing from among 29 families of students enrolled in the 2nd grade of a public elementary school in the urban periphery of the municipality of Garanhuns, PE.

Because studies have shown that fathers, mothers, and grandmothers feed their children and grandchildren differently11, and although mothers tend to be the primary caregiver12, we included all of these individuals as caregivers this study (table 1). This decision is in accordance with the Statute of Children and Adolescents (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente - ECA) (Federal Law No. 8069/90 - This federal law guarantees the rights of children and adolescents to access a food and parental care), which considers parents, and grandmothers to be responsible for caring for their children.

This study was approved by the Regional Education Management of Agreste Meridional (Gerência Regional de Educação do Agreste Meridional - GRE 11) and by the administration of the school. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health, University of São Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil. All of the respondents provided informed consent to participate in the study.

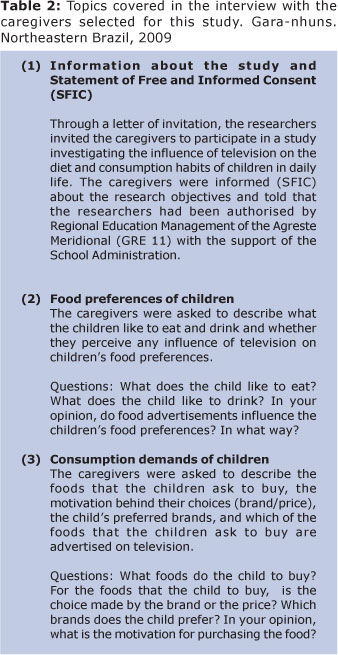

A topic guide was created to assist the caregivers in describing the influence of television on the food preferences and consumption habits of children. The caregivers were also asked about their perceptions of children's requests (i.e., their consumption demands and what the children ask to buy). The interview topics are described in table 2.

The questions were open-ended, and the interview guide was flexible. In general, such phrases as "can you say more?" encouraged the respondents to continue. The participants were informed that there were no right or wrong answers and that all information they provided was anonymous12.

The caregivers were also encouraged to consider all of the children they cared for who were enrolled in the study school. The interviews, each of lasted between 15 and 30 minutes in length, were recorded. In the transcription all spoken and non-verbal expressions were included. Data collection was conducted until thematic saturation was reached12.

Analysis

We produced an in-depth description of caregivers' experiences with children's food preferences and the influence of television. These results provided the framework for thematic analysis 12. The transcripts were coded using semantic analysis (surface meaning) and latent analysis (between-the-lines ideas, assumptions, and concepts) while rereading the transcripts using a dialogical approach13.

To compose the thematic framework, a broad set of codes was created based on theories by Castro8, Bauman 14, 15 and Beck16. The frameworks were reviewed by three researchers to avoid interpretation bias. To ensure that the data reflected the perceptions of the respondents, the codes and the themes were generated separately. The results were compared to verify the similarities and the differences among them12.

The analysis of the responses was substantiated using socio-historical theory proposed by Vygotsky 17 and Bakhtin18, a theoretical framework that enabled us to understand the caregivers' perceptions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of our analysis showed that caregivers perceive that television influences the eating habits of children.

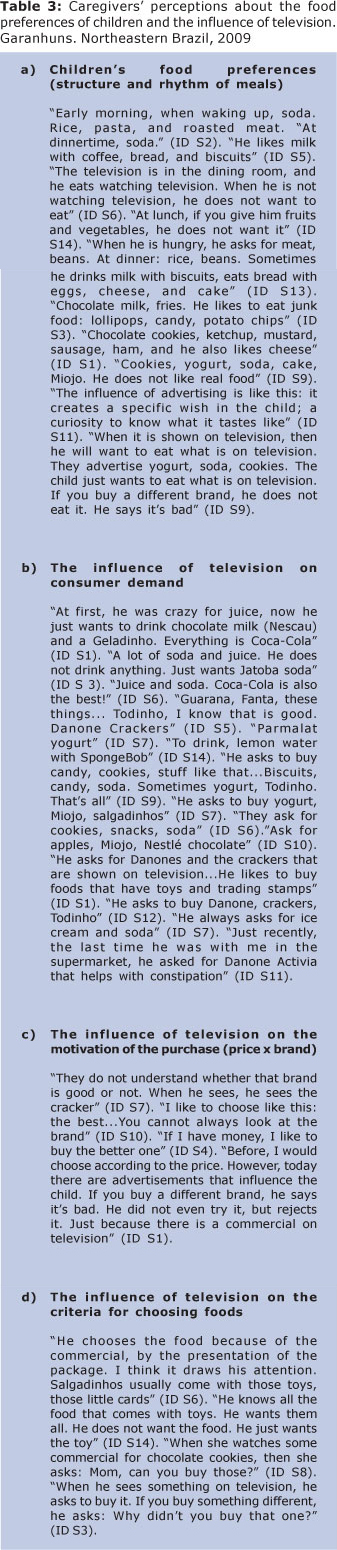

As shown in table 3, children are encouraged by advertisements "(...) that are shown on television" (ID S1), although family income is a stronger influence, given the socioeconomic profile of the families in this study. (Strikingly, family income in this region is less than twice the legal minimum wage, i.e.U$$ 391.77 - 2009).

Thus, children stop creating their own toys and start to request toys that are associated with food. "He knows all the food with toys (...) He does not want the food. He just wants the toy "(ID S14).

The purchasing decisions of caregivers are regulated by advertisements. "When he sees something on television, he asks to buy it" (ID S3). The preferences and eating habits of children are influenced by what is shown on television. "He chooses food because of the commercial (...)" (ID S6).

In this context, the caregiver's choice of food no longer depends on knowledge about nutritional information, food traditions, or home economics (and family income in this region is less than twice legal minimum wage).

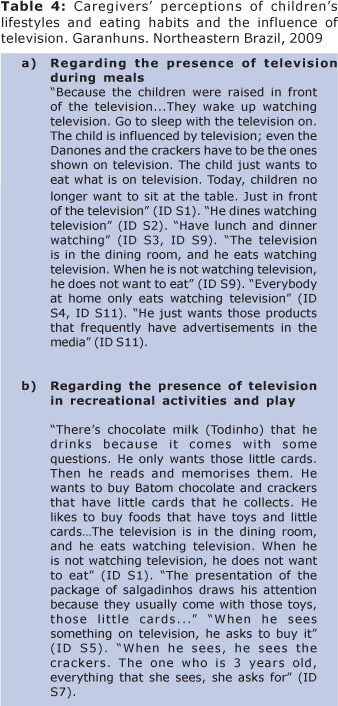

A new order begins to take over the caregiver-child relationship. Family relationships change in relation to food consumption, as do the relationships between children and food, food and nutrition, and bodies and health. The order of desire is influenced by the media, and television supports these narratives, as shown in Table 4.

International studies of children show that television increases food intake and obesity. These studies have shown that body fat percentage increases as television exposure increases19 and that childhood diabetes is strongly associated with prolonged exposure to television20.

In the United States, a review found that children watch approximately 20 hours of television per week, and approximately 3 hours are food advertisements. In total, 91% of the advertisements are for foods with high fat, sugar, and salt content21.

According to Castro et al, 47,4% of Brazilian Children spend a total of least six hours a day in front of the television, playing video games, and on the computers, and these activities together lead the children to exercise some influence on 80% of their families' buying decisions22. This behaviour was also identified by the IBOPE1, which showed that Brazilian children spend an average of five hours per day watching television and that it takes approximately 10 seconds for a child to change his/her mind. The amount of time Brazilian children spend watching television is among the highest in the world. Even recreational games and other recreational activities traditionally associated with running and jumping are now performed with a remote control from the comfort of the couch and in the safety of the living room. Thus, new generations have been rapidly learning the unhealthy habits that stem from the behavioural changes associated with television. Moreover, feeding practices are grounded in culture23.

In Northeastern Brazil, where child malnutrition was once highly significant, studies on obesity and overweight have been limited to specific segments and different age groups, and use different nutrition indicators. In Campina Grande a high prevalence of overweight and obesity was found among schoolchildren. This can be explained by their unhealthy eating habits 24.

Systemic droughts are one of the primary topographic features of this urban-rural region that is marked by extreme poverty. Poverty is the cause of a number of health problems not observed elsewhere. This influence can be observed in the caregivers' responses; however, the caregivers cannot understand the magnitude of the influence of television on the lives of the children for whom they care. Understanding this magnitude is a challenge raised by this study.

Therefore, this study showed that child caregivers perceive that television influences the lifestyles and daily eating habits of Brazilian children, who, in turn, influence their families.

There has not only been a change in language and culture. There has been a transformation of the understanding of the relationships between bodies and health, food and nutrition, and individuals and society in a generation in which eating has left the table and eating behaviours extend beyond the dimensions of food and tradition.

Food and the act of eating have broken boundaries, requiring new languages, other places, and other foundations that are no longer real (the table), but virtual (the television). The food has become virtualised.

Knowledge and flavours have become globalised, broken geographic and cultural barriers, and integrated new cultures and paradigms. Children have embarked on this media trip, taking their caregivers along with them.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There were no potential conflicts of interest, including political and/or financial interests associated with patents or property, provision of materials, and/or supplies and equipment used in the study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for granting the Ph.D fellowship, which allowed us to conduct this study in another state of the federation.

FUNDING SOURCES

This study was developed with a fellowship [Ph.D.] from the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES).

REFERENCES

1. Nishida C, Uauy R, Kumanyika S, Shetty P. The Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: process, product and policy implications. Public Health Nutrition 7(1A), 245 - 250. [ Links ]

2. Jelliffe DI, Jelliffe EF. The incidence of protein-calorie malnutrition of early childhood. Am J Public Health 1963; 53(6): 905-912. [ Links ]

3. Giddens A. The consequences of modernity (As consequências da modernidade) 2nd ed, Ed Unesp: São Paulo, 1991, p.45-51. [ Links ]

4. Castells M. The rise of network society, Blackwell: Oxford and Malden, Mass, 1996, p.17, 199. [ Links ]

5. Lévy P. Collective intelligence. For an anthropology of cyberspace (A inteligência coletiva. Por uma antropologia do ciberespaço), Loyola: São Paulo, 1998, p.17 -29. [ Links ]

6. Santaella L, Lemos R. Digital social networks: the cognitive connections of Twitter (Redes sociais digitais: a cognição conectiva do twitter), Paulus: São Paulo, 2010, p.13-26. [ Links ]

7. Marques de Melo J. Panorama da comunicação e das telecomunicações no Brasil 2011/2012 - Indicadores. In. Ipea: Brasília, 2012, p.29-37. [ Links ]

8. Castro J. Hunger: a forbidden subject, the last writings of Josue de Castro (Fome: um tema proibido, últimos escritos de Josué de Castro), Edited byAna Maria de Castro, Civilização Brasileira: Rio de Janeiro, 2003, p.79 -149. [ Links ]

9. Batista Filho M. Forum. Centenary of Josue de Castro: lessons from the past, reflections for the future. (Fórum. Centenário de Josué de Castro: lições do passado, reflexões para o futuro). Introdução. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008; 24(11): 2695-97. [ Links ]

10. Estatística IIBdGe. Household Budget Survey (Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares), 2008-2009, IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, 2010, p.62-85. [ Links ]

11. Blisset J, Meyer C, Haycraft E. Maternal and paternal controlling feeding practices with male and female children. Appetite 2006; 47: 212-219. [ Links ]

12. Webber L, Cooke L, Wardle J. Maternal perception of the causes and consequences of sibling differences in eating behaviour. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010; 64: 1316-1322. [ Links ]

13. Bakhtin MM. Problems with Dostoevsky's poetry (Problemas da poética de Dostoievski), Forense Universitária: Rio de Janeiro, 1981, p.17-35; 106. [ Links ]

14. Bauman Z. Liquid times (Tempos líquidos), Translation by Carlos Alberto Medeiros, Jorge Zahar Ed: Rio de Janeiro, 2007, p. 86-7. [ Links ]

15. Bauman Z. Life for consumption: the transformation of people into commodities (Vida para consumo: a transformação das pessoas em mercadorias), Translation by José Gradel, Jorge Zahar Ed: Rio de Janeiro, 2008, p. 8-17; 137. [ Links ]

16. Beck U. Risky society: toward another modernity (Sociedade de risco: rumo a uma outra modernidade), Translation by Sebastião Nascimento, Ed 34: São Paulo, 2010, p.189-196. [ Links ]

17. Vygotsky LS. The social formation of mind (A formação social da mente), Martins Fontes: São Paulo, 1984, p. 95-134. [ Links ]

18. Bakhtin MM. Freudianism: a critical sketch (O freudismo: um esboço crítico), Ed Perspectiva: São Paulo, 2001, p.85-91. [ Links ]

19. Molina MC, López PM, Faria CP, Cadê NV, Zandonada E. Socioeconomic predictors of the quality of food for children (Preditores socioeconômicos da qualidade de alimentação de crianças). Rev Saúde Pública 2010; 44(5): 785-92. [ Links ]

20. Kameswararao AA, Bachu A. Survey of child diabetes and the impact of school level educational interventions in rural schools in Karimnagar district. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries 2009; 29(2): 69-73. [ Links ]

21. Taras H, Gage M. Advertised foods on children's television. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995; 149(6): 29-37. [ Links ]

22. Castro TG, Novaes JF, Silva MR, Costa NM, Franceschini SC, Tinoco AL et al. Characterization of dietary intake, socio-economic status and nutritional status of preschool children in municipal day care centers (Caracterização do consumo alimentar, ambiente sócio-econômico e estado nutricional de pré-escolares de creches municipais). Rev Nutr 2005; 18(3): 321-30. [ Links ]

23. Dalla Nora NC. Who comes, who goes: the politics of land distribution in Rio Grande do Sul - the case of Jeboticaba (Quem chega, quem sai: a política de distribuição de terras no Rio Grande do Sul - o caso de Jeboticaba), Ed UPF: Passo Fundo, 2006. [ Links ]

24. Medeiros CCM, Cardoso MAA, Pereira RAR, Alves GTA, Franca ISX et al. Nutritional status and habits of life in school children. Journal of Human Growth and Development 2011; 21(3):789-797. [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

Sophia Motta-Gallo

Manuscript submitted Nov 11 2012

Accepted for publication Dez 30 2012.