Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

versión impresa ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. v.42 n.1 Porto Alegre abr. 2008

Testing zimbardo time perspective inventory in a brazilian sample

Testando lo inventario de la perspectiva temporal de zimbardo en una muestra brasileña

Taciano L. MilfontI, II, 1; Palloma R. AndradeIII; Viviany S. PessoaIV; Raquel P. BeloIV

I Universidade Federal de Alagoas, Brazil

II University of Auckland, New Zealand

III Institute of Renewed Teaching of Paraíba, Brazil

IV Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the construct and discriminant validity of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI) in a sample of 247 undergraduate Brazilian students. The ZTPI five-factor structure, comprised by Past-Negative, Present-Hedonistic, Future, Past-Positive and Present-Fatalistic, provided acceptable fit to the data, and was statistically better fitting than competing models. Present-Hedonistic correlated positively with alcohol consumption and negatively with religiosity, Future correlated positively with health concern, and negatively with alcohol consumption, and Past-Positive correlated positively with wristwatch use. Findings were in line with previous studies, indicating that both the five time perspective dimensions can be identified cognitively, and their pattern of relationships with other variables are comparable across cultures.

Keywords: Time perspective, Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory, ZTPI, Brazil, Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

RESUMEN

Éste artículo evalúa la validez de constructo y la validez discriminante del Inventario de Perspectiva Temporal de Zimbardo (Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory, ZTPI) de una muestra de 247 estudiantes brasileños. La estructura de cinco-factores de ZTPI, definidos por Pasado-Negativo, Presente-Hedonístico, Futuro, Pasado-Positivo y Presente-Fatalista, provee un ajuste aceptable de los datos, y pareció ser mejor estadísticamente que el ajuste de los modelos alternativos. El Presente-Hedonístico fue positivamente correlacionado con el consumo de alcohol y negativamente con la religiosidad, el Futuro fue correlacionado positivamente con la preocupación por la salud y negativamente con el consumo de alcohol, y el Pasado-Positivo fue positivamente correlacionado con el uso del reloj. Los resultados encontrados concuerdan con los estudios anteriores, indicando que las cinco dimensiones de perspectiva del tiempo pueden ser identificadas cognitivamente. Además los patrones de correlación con otras variables son comparables a través de otras culturas.

Palabras clave: Perspectiva Temporal, Inventario de Perspectiva Temporal de Zimbardo, ZTPI, Brasil, Análisis Factorial Confirmatório.

"Man measures time and time measures man"

Italian proverb

Any human activity is embodied in temporal aspects. In fact, the distinction between humans and other animals seems to rely on our ability to travel mentally in time (Suddendorf & Corballis, 1997), and this ability is even argued to constitute the forth dimension (Suddendorf, 1994). Fraisse (1963) argues, for instance, that "[h]uman equilibrium is too precarious to do without fixed positions in space and regular cues in time" (p. 290). A time orientation (i.e., long-term orientation) has even been proposed as a cultural value dimension (Hofstede, 2001).

Many time facets have been studied, such as pace of life, rhythm, time allocation, developmental cycles, time continuity and change, and temporal scales (McGrath, 1988a). This paper will focus on the pace of life, that, in turn, can be understood through the study of time perspective (TP) (see, e.g., Jones, 1988; Levine, 1988). It was mainly since Kurt Lewin's (1951) gestaltic life-space model, which stressed the weight of both the past and the future on present behaviour, that TP has been extensively studied (see, e.g., McGrath, 1988b; Strathman & Joireman, 2005). Lewin (1951) defined this construct as "the totality of the individual's views of his psychological future and psychological past existing at a given time" (p. 75). Hence, TP enables us to understand why individuals are influenced to behave by their view of the future, by their recollections of the past, or by present exigencies (Karniol & Ross, 1996), and it is argued to be a "fundamental and vital psychological construct" (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999, p. 1284).

Several measures have been developed to capture TP (see, e.g., Bond & Feather, 1988; Drakulic, Tenjovic, & Lecic-Tosevski, 2003; Nurmi, Seginer, & Poole, 1990; Rojas-Méndez, Davies, Omer, Chetthamrongchai, & Madran, 2002; Shirai, 1994). It has been argued, however, that many of these measures present psychometric and theoretical limitations (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Moreover, previous attempts to measure TP have mainly focused on just one dimension, with future as the principal dimension of interest (Gjesme, 1983; Strathman, Gleicher, Boninger, & Edwards, 1994; Zaleski, 1994).

The Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI, Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999) was therefore chosen as a TP measure for four main reasons: (1) it is a multi-item scale, and one of the few measures that is concerned with the multidimensional nature of human temporality; (2) it comprises more than 20 years of an intensive research program on TP; (3) it has been used in several studies, with demonstrated validity and reliability (see, e.g., Breier-Williford & Bramlett, 1995; MacKillop, Anderson, Castelda, Mattson, & Donovick, 2006); and (4) it has already been used in different countries (see Apostolidis & Fieulaine, 2004; D'Alession, Guarino, De Pascalis, & Zimbardo, 2003; Lennings, 2000).

Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI)

Following the Lewinian tradition, Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) defined TP as the "nonconscious process whereby the continual flows of personal and social experiences are assigned to temporal categories, or time frames, that help to give order, coherence, and meaning to those events" (p. 1271). They developed the ZTPI to measure five such time frames: Past-Negative, Present-Hedonistic, Future, Past-Positive, and Present-Fatalistic. (A further dimension, Transcendental-Future, was also proposed and measured by Boyd and Zimbardo (1997), but is not considered here.) The ZTPI five dimensions have been related to several constructs. A brief description of these dimensions and their correlations with other constructs are described below. Because of space constraints the correlations will not be discussed here, but the interested reader should refer to the original research.

Past-Negative. This TP dimension reflects a pessimistic, negative, or aversive attitude toward the past. Past-Negative was positively associated with depression, anxiety, and aggression (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999); physical activity (Hamilton, Kives, Micevski, & Grace, 2003); and the use of approaches that search for meaning in study (Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2004). Conversely, Past-Negative was negatively associated with students' satisfaction with their university experience. Moreover, both pathological gamblers and psychiatric patients presented higher scores in Past-Negative than social gamblers (Hodgins & Engel, 2002).

Present-Hedonistic. This dimension reflects a hedonistic orientation attitude toward time and life. It was positively associated with scales measuring ego undercontrol, novelty, and sensation seeking (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999); health responsibility and interpersonal relations (Hamilton et al., 2003); substance use (Keough, Zimbardo, & Boyd, 1999); and risky driving (Zimbardo, Keough, & Boyd, 1997). In contrast, Present-Hedonistic was negatively associated with a measure of preference for consistency, religiosity, and wristwatch use (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999); and environmental behaviour (Corral-Verdugo, Fraijo-Sing, & Pinheiro, 2006). Pathological gamblers presented higher scores in this dimension than both social gamblers and psychiatric patients (Hodgins & Engel, 2002), while male and younger individuals presented higher scores than female and older individuals (D'Alessio et al., 2003; Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2004; Keough et al., 1999; Zimbardo et al., 1997).

Future. This dimension reflects planning for, and achievement of, future goals, characterizing a general future orientation. Future was positively correlated with conscientiousness, preference for consistency, a consideration of future consequences measure, and self-report hours spent studying per week (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999); health responsibility (Hamilton et al., 2003); perceived control, positive well-being, adaptive (behavioural, cognitive, and distract) coping, positive affective symptomatology, and resistance efficacy (Wills, Sandy, & Yaeger, 2001); students' satisfaction with their university experience, and the use of approaches that search for both meaning and reproduction in study (Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2004); and environmental attitudes and behaviour (Corral-Verdugo et al., 2006; Milfont & Gouveia, 2006). Conversely, Future was negatively correlated with novelty and sensation seeking, anxiety, and depression (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999); age (Hamilton et al., 2003); substance use (Keough et al., 1999); and risky driving (Zimbardo et al., 1997). Female presented higher scores than male in this TP dimension (Keough et al., 1999; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999; Zimbardo et al., 1997).

Past-Positive. This dimension embodies a warm, sentimental, nostalgic, and positive construction of the past. It was positively correlated with self-esteem and wristwatch use (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999); health responsibility, nutrition, and spiritual growth (Hamilton et al., 2003); and the use of approaches that search for both meaning and reproduction in study (Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2004). In contrast, Past-Positive was negatively correlated with aggression, depression, and anxiety (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Both pathological gamblers and psychiatric patients presented higher scores in Past-Positive than social gamblers (Hodgins & Engel, 2002), while female presented higher scores than male (Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2004; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999).

Present-Fatalistic. This TP dimension reflects a fatalistic, helpless, and hopeless attitude toward the future and life. Present-Fatalistic was positively associated with aggression, anxiety, and depression (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999); and physical activity (Hamilton et al., 2003). Conversely, it was negatively associated with consideration of future consequences (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999); students' satisfaction with their university experience, and the use of approaches that search for meaning in study (Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2004); and environmental behaviour (Corral-Verdugo et al., 2006). Both pathological gamblers and psychiatric patients presented higher scores in this dimension than social gamblers (Hodgins & Engel, 2002), while female and older individuals presented higher scores than male and younger individuals (D'Alession et al., 2003).

TP are thus expressed through these five ZTPI dimensions, and individuals may differ from one another in the degree to which they assign more emphasis in one particular dimension. It is important to point out, however, that human behaviour is more a mixture of all TP dimensions rather than a pure expression of any dimension in particular (Jones, 1988; Zimbardo, 2004).

The Present Study

The present study aimed to examine the construct validity of the ZTPI in a Brazilian sample. Therefore, this study can be classified as a psychological difference study (van de Vijver & Leung, 2000), and it follows several studies attempting to validate psychological measures developed elsewhere into the interamerican context (see, e.g., Acuna, Brunner, & Avila, 1994; Alfaro-Garcia & Santiago-Negron, 2002; Bauermeister, Colon-Fumero, Villamil-Forastieri, & Spielberger, 1986; Manso-Pinto, 2006; Paine & Garcia, 1974). First, the cross-cultural stability of the factor structure of the ZTPI was tested. In line with previous findings (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999), it was expected that the five-factor structure of the ZTPI (i.e., Past-Negative, Present-Hedonistic, Future, Past-Positive, and Present-Fatalistic) would fit the Brazilian data well, and to be statistically better fitting than alternative models. Second, the discriminant validity was assessed by investigating the pattern of relationships between the ZTPI scales and other variables. Based on previous findings some predictions were made: (a) Present-Hedonistic was expected to be positively correlated to alcohol consumption (Keough et al., 1999), and negatively correlated to both religiosity and wristwatch use (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999), (b) Future was expected to be positively correlated to health concern (Strathman et al., 1994), and negatively correlated to both alcohol consumption (Keough et al., 1999) and self-perceived family economic status (Epel, Bandura, & Zimbardo, 1999), (c) Past-Positive was expected to be positively correlated to wristwatch use (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999), and (d) male and younger individuals were expected to score higher than female and older individuals in Present-Hedonistic (D'Alession et al., 2003; Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2004; Keough et al., 1999; Zimbardo et al., 1997), whereas female individuals were expected to score higher than male individuals in both Future and Past-Positive (Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2004; Keough et al., 1999; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999; Zimbardo et al., 1997).

Method

Sample

A questionnaire-based study was conducted with 247 undergraduate students (147 females and 100 males) from Joao Pessoa, Brazil. The students' average age was 22.47 years (SD = 4.19). Data was also colleted from 16 elderly (8 females; 8 males), with age ranging from 61 to 88 years (M = 69.31; SD = 1.50) from the same city. This latter sample was used to further investigate the age relation to TP.

Instruments

Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory. A Brazilian-Portuguese version of the ZTPI was used in this study. It contains 56 items that measure the five TP dimensions described above: Past-Negative ("I think about the bad things that have happened to me in the past"), Present-Hedonistic ("I take risks to put excitement in my life"), Future ("I complete projects on time by making steady progress"), Past-Positive ("It gives me pleasure to think about my past"), and Present-Fatalistic ("My life path is controlled by forces I cannot influence") (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Respondents rate each item on a 5-point scale from 1 (very untrue/uncharacteristic) to 5 (very true/characteristic).

Single Self-Report Items. Three sets of single self-report items were used to assess the pattern of relationships between the ZTPI scales and other variables: (1) Socio-demographic questions. Age, gender, religiosity (on a 8-point scale anchored by not religious at all and very religious), and self-perceived family economic status (on a 9-point scale anchored by lower income and upper income) were measured. (2) Health and time concerns. Participants rated how concerned they were, in general, about their health and to know the right time (both questions using a 5-point scale anchored by not at all concerned and extremely concerned). Participants also rated how often they wear a wristwatch (on a 5-point scale anchored by never and always). (3) Drink habits. Participants rated the most they had drunk on a single occasion in the last month and the average number of drinks consumed on a typical weekend (both questions using a 9-point scale anchored by 0 drinks and 15 or more drinks) (Keough et al., 1999). These items correlated substantially (r = .85, p < .001), which allowed us to create a single drink habit index by averaging the scores on these questions.

Producing a Brazilian-Portuguese version of the ZTPI

The ZTPI was adapted into Brazilian-Portuguese using a bilingual committee approach (van de Vijver & Leung, 1997). This first Brazilian-Portuguese version was then administered to two bilinguals Brazilians residents in New Zealand for their comments. After modifications, a revised version was administered in a pilot study in Brazil. Checks on translation accuracy were completed with subsequent correction when necessary. The ZTPI Brazilian-Portuguese version is shown in Appendix A.

Procedure

The questionnaires were completed by the students individually in a classroom setting, and by the elderly sample in their home. An average of 30 minutes was necessary for participants to complete the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and confidential. Multiple imputation using the EM algorithm (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996) was used to replace isolated missing values (0.81%) in the data set. Confirmatory factor analysis models were examined using LISREL version 8.54 and maximum likelihood estimation (Jöreskog, Sörbom, Du Toit, & Du Toit, 2000). Standard maximum likelihood LISREL fit indices with a c2/df (the ratio of chi-square to degree of freedom) in the range of 2 to 3 indicate acceptable fit (Carmines & McIver, 1981). GFI (goodness of fit index), CFI (comparative fit index), RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) and SRMR (standardized root mean square residual) having values respectively close to .95, .95, .06 and .08 indicate acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The c2 difference test, the ECVI (expected cross-validation index), and the CAIC (consistent Akaike information criterion) were also examined to calculate significant improvement over competing models. Significant results of the c2 difference test, and lower ECVI and CAIC values reflect the model with the better fit (Garson, 2003).

Results

Three sets of analyses were conducted to meet the present study's objectives. First, confirmatory factor analysis were performed to assess the factor structure of the ZTPI. Second, intercorrelations, internal consistency, and homogeneity were assessed to check the reliability of the ZTPI scales. Third, correlations were performed to assess the relationships between the ZTPI and other variables.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the ZTPI

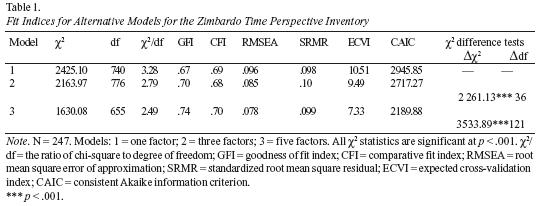

As substantial evidence exists regarding the factor structure of the ZTPI, confirmatory factor analysis were used (Fabrigar, MacCallum, Wegener, & Strahan, 1999). Three alternative models were evaluated. Model 1 tested a unidimensional model, where all 56 ZTPI items were specified to load on a single factor. In Model 2, a three-factor solution was tested, where the Past-Negative and Past-Positive items were specified to load together on one factor (i.e., a Past factor), the Present-Fatalistic and Present-Hedonistic items were specified to load together on the second factor (i.e., a Present factor), and Future items were specified to form the third factor (i.e., a Future factor). Finally, in Model 3 the items were specified to load o their theoretical factor, as specified by Zimbardo and Boyd (1999). Table 1 presents the fit statistics for each of these three competing models. For each model some items presented non-significant (t<1.96, p>0.05) loadings, and were excluded. So, Model 1 ended up with 40 significant-loading items, Model 2 with 41, and Model 3 with 38.1 As can be seen in Table 1, all three models tested had indicators of fit below the recommended values. In line with predictions, however, the five-factor model provided the best fit to the data, and was statistically better fitting than the other competing models. The five-factor model was therefore used in the further analyses. The 38 significant-loading items were then averaged to form the scale score for each ZTPI scale.

Intercorrelation, and Reliability of the ZTPI Scales

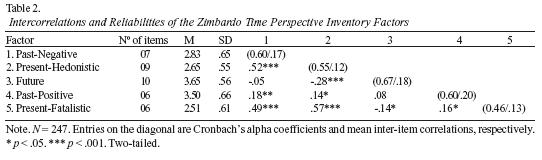

The sample means, standard deviation, intercorrelations between the ZTPI scales, and their reliabilities (both internal consistency and homogeneity) are reported in Table 2. Future was the scale with the higher mean rating, while Present-Fatalistic presented the lower mean rating for the Brazilian sample. More than half of the intercorrelations between the ZTPI scales presented the same pattern found previously (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). However, in the present study the correlations between Future and both Past-Negative and Past-Positive were in the expected direction but not significant. In addition, the correlations between Past-Negative and Past-Positive, and Past-Positive and Present-Fatalistic were positively correlated in the present study. Both the Cronbach's alpha coefficients and the mean inter-item correlations of the ZTPI scales were below the optimal level (Briggs & Cheek, 1986; Nunnally, 1978). However, Cronbach's alpha coefficients and mean inter-item correlations respectively of .60 and .15 or better have also been argued as acceptable for research purposes (Clark & Watson, 1995; Mueller, 1986), specially for broad constructs, such as the broad ZTPI dimensions. Thus, following these recommendations most of the scales had acceptable reliabilities.

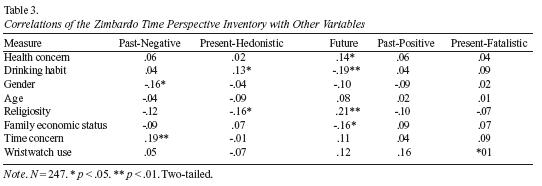

Relations of the ZTPI and Other Variables

Table 3 shows the correlations between the ZTPI scales and other measures. In line with predictions, Present-Hedonistic correlated positively with drinking habit, and negatively with religiosity and wristwatch use (but not reaching significance); Future correlated positively with health concern, and negatively with both alcohol consumption and self-perceived family economic status; and Past-Positive correlated positively to wristwatch use. Moreover, Past-Negative correlated positively to time concern, and Future correlated positively to religiosity. In contrast to previous studies and our own predictions, Past-Negative was the only factor associated with gender for the Brazilian sample, with female (M = 2.95, SD = 0.63) scoring higher than male (M = 2.76, SD = 0.71) participants, t (261) = 1.91, p < .05 (two-tailed), d = .28. Finally, even though none of the ZTPI scales showed associations with age, we decided to investigate age differences further. The mean scale scores from the youngest sixteen university students, with average age of 17.31 years (SD = 1.40), were compared to those scores from the elderly sample. There were mean score differences for two ZTPI dimensions. The elderly sample (M = 4.04, SD = 0.61) scored higher than the youngest sample (M = 3.42, SD = 0.77) in the Past-Positive factor, t(30) = 2.55, p < .05 (two-tailed), d = .89. The elderly sample (M = 3.20, SD = 0.72) also scored higher than the youngest sample (M = 2.39, SD = 0.53) in the Present-Fatalistic factor, t(30) = 3.65, p < .01 (two-tailed), d = 1.29.

Discussion

Time perspective seems a crucial psychological construct, as any human activity is embodied in temporal aspects. Although several measures have been developed to capture this construct, many present psychometric and theoretical limitations. The Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI, Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999), however, seems to overcome most of the limitations of the concurrent measures by utilizing multi-item scales, and being concerned with the multidimensional aspect of time perspective. Specifically, the ZTPI measures five time frames: Past-Negative, Present-Hedonistic, Future, Past-Positive, and Present-Fatalistic. The present paper sought to test the cross-cultural stability of the factor structure of the ZTPI, and to assess the pattern of relationships between the ZTPI scales and other variables.

In line with predictions, the ZTPI five-factor structure presented better fit indices, and was statistically better fitting than both a unidimensional and a three-factorial solution. This result supports Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) claim that the ZTPI items express five time frames. More importantly, it indicates that the five time perspective dimensions can be identified cognitively across cultures. It is important to note, however, some psychometric limitations of the ZTPI for the Brazilian sample. The ZTPI presented low fit indices, low reliabilities, and eighteen non-significant items were excluded. Although the elimination of items does not seem to affect the integrity of the entire scale, as there were still enough items for each of the five dimensions, it may express problems on the ZTPI items. Although the ZTPI items were conceived to express social attitudes and beliefs, an inspection of the ZTPI items indicates that some of them pertain to personality traits and behaviour (J. Duckitt, personal communication, May 17, 2004). Therefore, new studies may attempt to refine the ZTPI items, excluding the personality orientated ones, such as "Painful past experiences keep being replayed in my mind" and "I do things impulsively".

However, despite these psychometric limitations the relationships between the ZTPI scales with other variables where in line with previous studies. The results indicated that people who uphold a future orientation tend to present both more concern about their health and a reduced drinking habit, supporting previous findings (Keough et al., 1999; Strathman et al., 1994). In contrast, people who uphold present-hedonistic orientation tend to present a higher drinking habit. In addition, people who uphold past orientations tend to present a higher time concern, in a more abstract way (i.e., concern to know the right time) for past-negative orientated individuals, and in a more pragmatic way (i.e., using a wristwatch) for past-positive orientated individuals. Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) also found that past-positive oriented individuals were more likely to keep a clock on their desks.

Furthermore, supporting our prediction and previous findings (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999), Present-Hedonistic presented a negative correlation to religiosity, indicating that the "living for pleasure" orientation of this dimension do not mix to religious beliefs. Future was also correlated to religiosity. Although not predicted, this finding is comprehensible for two reasons. First, it follows the inverse pattern of correlations between both Present-Hedonistic and Future and other variables. Second, Future (a pre-death time frame) share similarities with Transcendental-Future (a pro-death time frame), and this latter dimension was found to positive correlate to religiosity (Boyd & Zimbardo, 1997). Thus, one would expect that future oriented individuals would also be religious oriented. Yet, Future was negatively correlated with self-perceived family economic status. Hence, those individuals who perceive their families as having a low economic status tend to be future oriented. Epel et al. (1999) found that future orientation presented a predictive power for proactive search behaviours (i.e., coping strategies related to obtaining housing and employment) in homeless adults. Hence, it seems that people's desire to change their low economic status may lead to a higher future orientation that, in turn, may lead to a more proactive behaviour to find alternatives to overcome their situation.

Nevertheless, the pattern of associations between the ZTPI scales and both gender and age found in previous studies (see, e.g., Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999; Zimbardo et al., 1997) were not found in this Brazilian sample. For this sample, only Past-Negative presented gender differences, with female scoring higher than male individuals. However, although there were no associations between the ZTPI scales with age for the student sample, when the scale scores of the youngest sixteen university students were compared to those scores of an elderly sample some interesting findings were obtained. The elderly sample scored higher than the youngest students in both Past-Positive and Present-Fatalistic. The past-positive orientation of the elderly individuals may reflect the reminiscence bump, that is, disproportionately higher recall of early-life memories (see Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). Thus, the tendency of older adults to recall early-life memories may lead then to be past-positive oriented. In contrast, the present-fatalistic orientation of the elderly individuals may reflect a hopeless attitude toward the future. Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) argue that this TP dimension "reveals a belief that the future is predestined and uninfluenced by individual actions" (p. 1278). Hence, for older adults a present-fatalistic orientation may be expected as their future is expectantly shorter. For instance, the elderly sample had mean age of 69 years and will probably have only few more years to live, as the life expectancy of men and women who were born in Brazil in 2000 were respectively 66.71 and 74.29 years, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, 2004). However, although these findings are theoretically sound, the elderly sample is underrepresented so that any conclusion may be biased. Hence, these findings should be taken with caution and will need to be replicated in future research.

It is important to highlight that the correlations between the measures showed small to medium effect sizes in terms of magnitude, according to Cohen's (1988) guidelines and recent empirical guidelines (Hemphill, 2003). However, small and medium effect sizes are not uncommon in psychology. For instance, analyzing the magnitude of meta-analytic effect sizes of 474 social psychology effects, Richard, Bond and Stokes-Zoota (2003) concluded that the effects typically yield a value of .21, and that 30.44% yielded an r of .10 or less. Thus, even small effect sizes can be practically important.

In conclusion, the findings present initial support for the construct validity of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the ZTPI. The overall findings were in line with previous studies, indicating that both the five time perspective dimensions can be identified cognitively, and their pattern of relationship with other variables are comparable across cultures. We believe these findings support the importance of time perspective, as temporal aspects are present in any human activity. As J. T. Frazer wrote, "tell me what to think of time, and I shall know what to think of you" (quoted by Levine, 1988, p. 50).

References

Acuna, L., Brunner, C. A., & Avila, R. (1994). Estructura factorial del inventario de roles sexuales de Bem en Mexico. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 28, 155-168. [ Links ]

Alfaro-Garcia, R. A., & Santiago-Negron, S. (2002). Estructura Factorial de la Escala de Autoconcepto Tennessee (Version en Espanol). Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 36, 167-189. [ Links ]

Apostolidis, T., & Fieulaine, N. (2004). Validation francaise de l'echelle de temporalite [The Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory]. Revue Europeenne de Psychologie Appliquee, 54, 207-217. [ Links ]

Bauermeister, J. J., Colon-Fumero, O., Villamil-Forastieri, B., & Spielberger, C. D. (1986). Confiabilidad y validez del inventario de ansiedad rasgo y estado para ninos puertorriquenos y panamenos. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 20, 1-19. [ Links ]

Bond, M. J., & Feather, N. T. (1988). Some correlates of structure and purpose in the use of time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 321-329. [ Links ]

Boyd, J. N., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1997). Constructing time after death: The transcendental-future time perspective. Time and Society, 6, 35-54. [ Links ]

Breier-Williford, S., & Bramlett, R. K. (1995). Time perspective of substance abuse patients: Comparison of the scales in Stanford Time Perspective Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, and Beck Hopelessness Scale. Psychological Reports, 77, 899-905. [ Links ]

Briggs, S. R., & Cheek, J. M. (1986). The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. Journal of Personality, 54, 106-148. [ Links ]

Carmines, E. G., & McIver, J. D. (1981). Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In G. W. Bohinstedt & E. F. Borgatta (Eds.), Social measurement: Current issues (pp. 65-115). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7, 309-319. [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Conway, M. A., & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107, 261-288. [ Links ]

Corral-Verdugo, V., Fraijo-Sing, B., & Pinheiro, J. d. Q. (2006). Sustainable behavior and time perspective: Present, past, and future orientations and their relationship with water conservation behavior. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 40, 139-147. [ Links ]

D'Alessio, M., Guarino, A., De Pascalis, V., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2003). Testing Zimbardo's Stanford Time Perspective Inventory (STPI) - short form: An Italian study. Time and Society, 12, 333-347. [ Links ]

Drakulic, B., Tenjovic, L., & Lecic-Tosevski, D. (2003). Time Integration Questionnaire. Construction and empirical validation of a new instrument for the assessment of subjective time experience. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19, 101-116. [ Links ]

Epel, E. S., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1999). Escaping homelessness: The influences of self-efficacy and time perspective on coping with homelessness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29, 575-596. [ Links ]

Fabrigar, L. R., MacCallum, R. C., Wegener, D. T., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4, 272-299. [ Links ]

Fraisse, P. (1963). The psychology of time. New York: Harper and Row. [ Links ]

Garson, G. D. (2003). PA 765 Statnotes: An online textbook. Retrieved February 07, 2004, from http://www2.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/pa765/statnote.htm. [ Links ]

Gjesme, T. (1983). Introduction: An inquiry into the concept of future orientation. International Journal of Psychology, 18, 347-350. [ Links ]

Hamilton, J. M., Kives, K. D., Micevski, V., & Grace, S. L. (2003). Time perspective and health-promoting behavior in a cardiac rehabilitation population. Behavioral Medicine, 28, 132-139. [ Links ]

Hemphill, J. F. (2003). Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. American Psychologist, 58, 78-80. [ Links ]

Hodgins, D. C., & Engel, A. (2002). Future time perspective in pathological gamblers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190, 775-780. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Horstmanshof, L., & Zimitat, C. (2004, July). Time for persistence. Paper presented at the 8th Pacific Rim First Year in Higher Education Conference, Melbourne, Australia. [ Links ]

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. [ Links ]

IBGE. (2004, August 30). Projeção da população do Brasil [Projection of the Brazilian population]. Retrieved December 15, 2005, from http://www.ibge.com.br/home/presidencia/noticias/30082004projecaopopulacao.shtm [ Links ]

Jones, J. M. (1988). Cultural differences in temporal perspectives: Instrumental and expressive behaviors in time. In J. E. McGrath (Ed.), The social psychology of time: New perspectives (pp. 21-38). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1996). PRELIS 2: User's reference guide. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International. [ Links ]

Jöreskog, K. G., Sörbom, D., Du Toit, S., & Du Toit, M. (2000). LISREL 8: New statistical features. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International. [ Links ]

Karniol, R., & Ross, M. (1996). The motivational impact of temporal focus: Thinking about the future and the past. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 593-620. [ Links ]

Keough, K. A., Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Who's smoking, drinking, and using drugs? Time perspective as a predictor of substance use. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 21, 149-164. [ Links ]

Lennings, C. J. (2000). The Stanford Time Perspective Inventory: An analysis of a test of temporal orientation for research in health psychology. Journal of Applied Health Behaviour, 2, 40-45. [ Links ]

Levine, R. V. (1988). The pace of life across cultures. In J. E. McGrath (Ed.), The social psychology of time: New perspectives (pp. 39-62). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in the social sciences: Selected theoretical papers. New York: Harper. [ Links ]

MacKillop, J., Anderson, E. J., Castelda, B. A., Mattson, R. E., & Donovick, P. J. (2006). Convergent validity of measures of cognitive distortions, impulsivity, and time perspective with pathological gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20, 75-79. [ Links ]

Manso-Pinto, J. F. (2006). Estructura factorial del Maslach Burnout Inventory—version Human Services Survey—en Chile. Revista Interamericana de Psicologia, 40, 111-114. [ Links ]

McGrath, J. E. (1988a). Introduction: The place of time in social psychology. In J. E. McGrath (Ed.), The social psychology of time: New perspectives (pp. 7-20). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

McGrath, J. E. (1988b). The social psychology of time: New perspectives. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Milfont, T. L., & Gouveia, V. V. (2006). Time perspective and values: An exploratory study of their relations to environmental attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 26, 72-82. [ Links ]

Mueller, D. J. (1986). Measuring social attitudes: A handbook for researchers and practitioners. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Nurmi, J., Seginer, R., & Poole, M. (1990). Future-orientation questionnaire. Helsinki, Finland: Department of Psychology, University of Helsinki. [ Links ]

Paine, P. A., & Garcia, V. L. (1974). A revision and standardization of the WISC verbal scale for use in Brasil. Revista Interamericana de Psicologia, 8, 225-231. [ Links ]

Richard, F. D., Bond, C. F., Jr., & Stokes-Zoota, J. J. (2003). One hundred years of social psychology quantitatively described. Review of General Psychology, 7, 331-363. [ Links ]

Rojas-Méndez, J. I., Davies, G., Omer, O., Chetthamrongchai, P., & Madran, C. (2002). A time attitude scale for cross cultural research. Journal of Global Marketing, 15, 117-147. [ Links ]

Shirai, T. (1994). A study on the construction of Experiential Time Perspective Scale. Japanese Journal of Psychology, 65, 54-60. [ Links ]

Strathman, A., Gleicher, F., Boninger, D. S., & Edwards, C. S. (1994). The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 742-752. [ Links ]

Strathman, A., & Joireman, J. A. (Eds.). (2005). Understanding behavior in the context of time: Theory, research, and application. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Suddendorf, T. (1994). Discovery of the fourth dimension: Mental time travel and human evolution. Unpublished Master's thesis, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand. [ Links ]

Suddendorf, T., & Corballis, M. C. (1997). Mental time travel and the evolution of the human mind. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs, 123, 133-168. [ Links ]

van de Vijver, F., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

van de Vijver, F., & Leung, K. (2000). Methodological issues in psychological research on culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 33-51. [ Links ]

Wills, T. A., Sandy, J. M., & Yaeger, A. M. (2001). Time perspective and early-onset substance use: A model based on stress-coping theory. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 15, 118-125. [ Links ]

Zaleski, Z. (1994). Psychology of future orientation. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL. [ Links ]

Zimbardo, P. G. (2004, August). Creating the optimally balanced time perspective in your life. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the New Zealand Psychological Society, Wellington, New Zealand. [ Links ]

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1271-1288. [ Links ]

Zimbardo, P. G., Keough, K. A., & Boyd, J. N. (1997). Present time perspective as a predictor of risky driving. Personality and Individual Differences, 23, 1007-1023. [ Links ]

Received: 28/03/2007

Accepted: 31/01/2008

1This research was made possible by scholarship BEX 2246/02-3 from the Ministry of Education of Brazil (CAPES Foundation) to the first author. Portions of this article were presented at the XXXV Annual Meeting of the Brazilian Psychological Society in Curitiba, Brazil.

1The items that had non-significant loadings were: 01, 02, 06, 07, 11, 15, 19, 20, 22, 24, 28, 31, 35, 36, 37, and 46 (Model 1); 01, 11, 17, 19, 22, 28, 31, 35, 36, 37, 45, 46, 51, 52, and 56 (Model 2); and 01, 17, 19, 22, 28, 31, 36, 45, 46, 50, 51, 56, 25, 29, 41, 35, 37, and 52 (Model 3).

Appendix A

Brazilian-Portuguese Version of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory

Past-Negative: Items 04, 05, 16, 22, 27, 33, 34, 36, 50 and 54.

Present-Hedonistic: Items 01, 08, 12, 17, 19, 23, 26, 28, 31, 32, 42, 44, 46, 48 and 55.

Future: Items 06, 09, 10, 13, 18, 21, 24, 30, 40, 43, 45, 51 and 56.

Past-Positive: Items 02, 07, 11, 15, 20, 25, 29, 41 and 49.

Present-Fatalistic: Items 03, 14, 35, 37, 38, 39, 47, 52 and 53.

1. Acredito que encontrar com amigos(as) para festejar é um dos prazeres mais importantes da vida.

2. Visões, sons e cheiros familiares da infância muitas vezes trazem de volta memórias maravilhosas.

3. O destino determina muita coisa em minha vida.

4. Eu freqüentemente penso no que deveria ter feito diferente em minha vida.

5. Minhas decisões são na maioria das vezes influenciadas pelas pessoas e coisas que estão ao meu redor.

6. Acredito que o dia da pessoa deva ser planejado no início de cada manhã.

7. Sinto prazer em pensar sobre o meu passado.

8. Faço as coisas impulsivamente.

9. Não me preocupo se as coisas não forem feitas dentro do prazo.

10. Quando quero alcançar algo, estabeleço objetivos e considero formas específicas para atingi-los.

11. Colocando em uma balança, existem mais coisas boas do que ruins para recordar do meu passado.

12. Quando escuto minhas músicas favoritas, perco toda a noção do tempo.

13. Cumprir os prazos para amanhã e fazer outros trabalhos necessários vêm antes da diversão noturna.

14. Já que as coisas serão do jeito que têm que ser, não importa o que eu faça.

15. Gosto de histórias sobre como as coisas costumavam ser nos "bons e velhos tempos".

16. Experiências dolorosas do passado permanecem sendo relembradas em minha mente.

17. Tento viver minha vida tão intensamente quanto possível, um dia de cada vez.

18. Fico chateado(a) quando me atraso para meus compromissos.

19. Idealmente, viveria cada dia da minha vida como se fosse o último.

20. Memórias felizes dos bons tempos aparecem facilmente na minha mente.

21. Cumpro minhas obrigações com amigos e autoridades no prazo.

22. Já recebi minha parte de crueldade e rejeição no passado.

23. Tomo decisões no impulso do momento.

24. Aceito cada dia como ele é, ao invés de tentar planejá-lo.

25. O passado tem tantas memórias desagradáveis que prefiro não pensar sobre ele.

26. É importante vivenciar experiências estimulantes em minha vida.

27. Cometi erros no passado que gostaria de poder desfazê-los.

28. Eu sinto que é mais importante aproveitar o que se está fazendo do que fazer as coisas no prazo.

29. Sinto-me nostálgico(a) com relação à minha infância.

30. Antes de tomar uma decisão eu peso os custos e benefícios.

31. Correr riscos evita que minha vida se torne chata.

32. Para mim é mais importante aproveitar a jornada da vida do que focalizar apenas o destino.

33. As coisas raramente funcionam como eu esperava.

34. Para mim é difícil esquecer imagens desagradáveis da minha infância.

35. Perde toda a alegria do processo e atrapalha o fluxo das minhas atividades, se eu tiver que pensar sobre seus objetivos, resultados e produtos.

36. Mesmo quando eu estou desfrutando o presente, sou levado(a) a fazer comparações com experiências similares do passado.

37. Não se pode fazer planos para o futuro porque as coisas mudam muito.

38. Meu caminho de vida é controlado por forças que não posso influenciar.

39. Não faz o menor sentido se preocupar sobre o futuro, uma vez que não existe nada que eu possa fazer.

40. Completo meus projetos na hora certa através de progressos contínuos.

41. Sinto-me "por fora" quando pessoas da minha família falam sobre como as coisas costumavam ser.

42. Corro riscos para tornar minha vida excitante.

43. Faço listas das coisas que tenho que fazer.

44. Freqüentemente sigo mais meu coração do que minha razão.

45. Sou capaz de resistir às tentações quando sei que existe trabalho a ser feito.

46. Pego-me sendo levado(a) pela excitação do momento.

47. A vida hoje em dia é muito complicada; eu preferiria a vida mais simples do passado.

48. Prefiro amigos(as) que são espontâneos àqueles(as) que são previsíveis.

49. Gosto das cerimônias e tradições familiares que são regularmente repetidas.

50. Penso nas coisas ruins que me aconteceram no passado.

51. Permaneço trabalhando em tarefas difíceis e desinteressantes se elas me ajudarem a seguir em frente.

52. Gastar o que eu ganho em prazeres hoje é melhor do que economizar para a segurança de amanhã.

53. Muitas vezes a sorte dá melhor resultados do que o trabalho duro.

54. Penso sobre as coisas boas que perdi em minha vida.

55. Gosto que minhas relações íntimas sejam apaixonadas.

56. Sempre existirá tempo para colocar meu trabalho em dia.