Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

versión impresa ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. v.42 n.1 Porto Alegre abr. 2008

Drug dependence, mental impairment and education

Dependencia de droga, debilitación mental y educación

Florindo StellaI, 1; Célia Regina RossiI; José Sílvio GovoneII

I UNESP - Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Biociências, Câmpus de Rio Claro, SP, Brasil

II UNESP - Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Geociências e Ciências Exatas, Câmpus de Rio Claro, SP, Brasil

ABSTRACT

This study aimed to evaluate the mental conditions of cocaine-dependent individuals and school commitment/attachment. We evaluated 50 patients referred to the psychiatry emergency room due to mental disorders from chemical dependence. After clinical diagnosis, clinical interview, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Hamilton Scale for Depression and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale were applied. The Spearman and Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests, as well as the t-Student test were utilized for statistical analysis.. The accepted significance value was 0.05. All subjects had used cocaine or crack and other substances. Only 13 (26%) did not drop out of school (group 1). Regarding the other 37 (74%), irregular class attendance , successive failures and definitive school drop out rates (group 2) were verified. These subjects presented an early substance use when compared with those which did not drop out of school (p=0.0001). Patients with an early substance use presented higher school dropout rates than those with a later initiation to substance use. Psychopathological phenomena were frequent in both groups.

Keywords: Mental distress, Psychoactive substance, Chemical dependence, School commitment/attachment.RESUMEN

El objetivo del estudio fue evaluar la relación entre las condiciones mentales de dependientes de sustancias psicoativas y el vínculo escolar. Fueron evaluados 50 participantes atendidos en emergencias psiquiátricas por trastornos mentales asociados a la dependencia química. Luego del diagnóstico clínico, fueron realizadas las siguientes estrategias metodológicas: Entrevista Clínica, Escala Hospitalaria de Ansiedad y Depresión, Escala de Depresión de Hamilton y Escala Psiquiátrica Breve. La análisis estadístico se expresó mediante testes no-paramétricos como correlación de Spearman, Mann-Whitney, y t-Student test, con nivel de significación de 0,05. Todos los participantes hacían uso de cocaína o crack con otras sustancias. Apenas 13 (26%) no interrumpen el vínculo escolar (grupo 1). Los demás, 37 participantes (74%), verificaron frecuencia irregular en aula, sucesivas reprobaciones y interrupción definitiva del vínculo escolar (grupo 2). Estos últimos participantes (con interrupción del vínculo escolar) habían iniciado el uso de sustancias psicoativas más precozmente cuando los comparamos con los primeros (sin interrupción del vínculo escolar) con diferencia significativa entre ambos (p=0,0001). En conclusión, los participantes que iniciaron tempranamente el uso de sustancias psicoativas presentaban tasas mayores de interrupción del vínculo escolar quando comparados con aquejes con inicio más tardío. Los fenómenos psicopatológicos eran frecuentes y graves en ambos grupos.

Palabras clave: Sufrimiento mental, Sustancias psicoactivas, Dependencia química, Vínculo escolar.

Drug addiction has become a serious public health and behavior problem among young people in the community (Flack et al., 2004). Alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, benzodiazepines, amphetamines, cocaine and crack, among other illegal substances, are frequently used by students. Cocaine dependence, in particular, represents a complex psychiatric disorder in this population. A study developed in ten Brazilian capitals with students from first to eight graders to high school students showed that cannabis is the most consumed illegal substance within the country, and that its use has increased throughout the last decades (Galduróz et al., 1997). From 1980 to 1990, there was an increasing use of psychoactive substances, including cocaine and crack, especially among students in school and in High School (Carlini et al., 1993; Napo et al., 1994; Galduróz et al., 1997). Abuse of these substances contributed significantly to a poor academic performance and school dropouts (Rimsza & Moses, 2005).

The chronic use of cocaine had been associated with the impairment of executive functions (Bolla et al., 2000; Hester & Garavan, 2004). In normal individuals, these mental processes are characterized by the ability to plan, goal setting and organizing behavior, for decision-making, working memory, attention span, as well as self-control. Cocaine-dependent individuals tend to present an impairment of their executive functions consequently, they present difficulties in controlling their own impulses. Neuropsychological tests in these individuals, in order to address executive functions, revealed poor performance especially in relation to tasks demanding planning, decision-making, working memory, attention span, and self-control (Fillmore & Rush, 2002; Verdejo-García et al. (in press) -García, 2006).

Cannabis, after a few years of use, causes cognitive impairment in organizing and integrating complex information, and in attention span and memory processes (Wert & Raulin, 1986). Cannabis abuse, even after shorter periods, may impair psychological functions, in addition to causing dependence (Ribeiro et al., 2005). Within the cognitive sphere, substance abuse may affect the learning process, concentration, attention span, and memory (Pope & Yurgelun, 1996). The magnitude of the cognitive impairment is associated with variables such as duration, frequency and the amount of cocaine and other substance abuse (Bolla et al., 2000; Di Sclafani et al., 2002).

In addition to the occurrence of cognitive impairment, students affected by chemical dependence report other symptoms such as depression, anxiety, personality disorders, circadian rhythm disturbance, aggressive behavior and psychosis (Hoff et al., 1996; Robinson et al., 1999; Bolla et al., 2000; Rosselli et al., 2001; Pace-Scott et al., 2005). The frequency of cocaine-dependent individuals among the occurrence of suicide in boys is four times more common and five times more common among suicide in girls than in the non-suicidal group (Voros et al., 2005). Psychosis is included among the more severe psychopathological conditions of cocaine dependence, and patients show subjective intense feelings of destructive behavior or fear of being harmed, despite knowing that it is irrational (Kalahari's et al., 2006). In consequence of chronic cocaine use, patients present structural and functional changes of several brain regions such as prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex - areas closely related to executive functions (Bolla et al., 2001; Kaufman et al., 2003; Hester & Garavan, 2004; Goldstein et al., 2004; Verdejo-García et al., in press). Neurotransmitter system changes in chronic cocaine-dependent individuals are frequent, and these alterations occur with lowered synaptic density of both serotonin and dopamine in the brain (Ghitza et al., 2007). According to these authors, decreased serotonin and dopamine transmission may contribute to psychopathological symptoms such as irritability, obsessive thoughts, loss of impulse control, and anhedonia. These changes in the brain probably contribute to the psychopathological status characterized by cognitive impairment, depression, anxiety, and psychotic symptoms. The aim of this study was to evaluate the mental condition of chemical-dependent individuals, especially cocaine, and to verify possible relationships between psychoactive substance abuse and school commitment.

Methods

In a consecutive series, fifty cocaine and crack-dependent individuals, who also frequently used other psychoactive substances, were studied. The subjects, who lived in Campinas and were being assisted at the State University of Campinas Teaching Hospital and the Tibiriçá Psychiatry Hospital, presented mental disorders related to chemical dependence, especially cocaine. The numerical difference between both genders is due to the prevalence of men in routine attendance. The participation of the subjects in the research occurred through informed consent of their relatives or people responsible for them or through the subjects themselves, when they were in condition to understand the nature and objectives of this work and agree to participate in this study.

Procedures

Subjects had used cocaine and other psychoactive substances in the last 24 hours before internment in the Psychiatric Emergency Service. Reports from patients or their relatives confirmed drug dependence. Due to the delay in performing laboratory exams in the Emergency Service, it was impossible to obtain blood or urinary data related to the drug use. The psychiatric interview and the scales were applied immediately after the acute phase management. There was no significant difference between sociodemographic characteristics and scale results in patients from both emergency services, as they were considered simultaneously. The methodological procedures consisted of the following steps:

1) A mental health expert performed a clinical interview in order to characterize the patient's history concerning the abuse of psychoactive substances, age at use onset, type of drug, mental comorbidities and psychiatric diagnosis. The diagnosis of chemical dependence followed the criteria established by the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; APA, 1994). Schooling period data and drug interference with school commitment were also included. Information regarding family relationships and regularity of professional activity completed the sociodemographic data. A detailed psychiatric examination identified the mental condition, and by means of interviews with relatives and professionals responsible for clinical attendance complete data was obtained.

2) In order to investigate the mental condition, the following scales were applied, considering the "cut-off point" between "case" and "non-case" that based on criteria established for our population:

a) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD - Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) was composed by two sub-scales, anxiety and depression respectively, to characterize these mental disorders. A score over 7 in each sub-scale suggests symptoms of anxiety or depression (Botega et al., 1995).

b) Hamilton Scale for Depression (Hamilton, 1960) includes 17 items. In clinical practice, the following "cut-off point" scores are largely accepted: below 7 for absence of symptoms; between 7 and 17 for mild depression; from 18 to 24 for moderate depression; and above 25 for severe depression (Del Porto, 1989; Moreno & Moreno, 2000).

c) The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS - Overall & Gorham, 1962) evaluated psychotic symptoms and thought disturbances. The clinical severity of BPRS symptoms was established in agreement with the arithmetic average of each domain of symptoms for all the subjects, by the following criteria: absence of symptoms (score: 0); mild symptoms (from 1 to 2); moderate symptoms (from 2 to 3); and severe symptoms (from 3 to 6). We adopted the four psychopathological domains recommended by several experts (Elkis et al., 2000; Romano & Elkis, 1996). There were: a) thought disturbance (conceptual disorganization, hallucinations and delusions, and alteration of the course of thoughts); b) withdrawal and psychomotor disturbances (emotional withdrawal, psychomotor slowness and blunted affective performance); c) hostility and suspicion (hostile behavior or suspicion and lack of cooperation in the interview); and d) anxiety and depression (anxious symptoms, guilty feelings and depressed mood). The sample was divided into two groups: Group 1 (psychoactive substance users with school commitment), and Group 2 (psychoactive substance school dropout users). School commitment included regular class attendance and regular participation in school activities, despite drug use. The lack of school commitment meant definitive interruption of class attendance due to psychoactive substances.

In order to calculate the correlation between results from scales or clinical features, we used the Spearman nonparametric correlation and by the t-Student test, we measured the significance of association among variables. We applied the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test to compare variables concerning demographic data, clinical features and scores from scales between both groups. A value of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

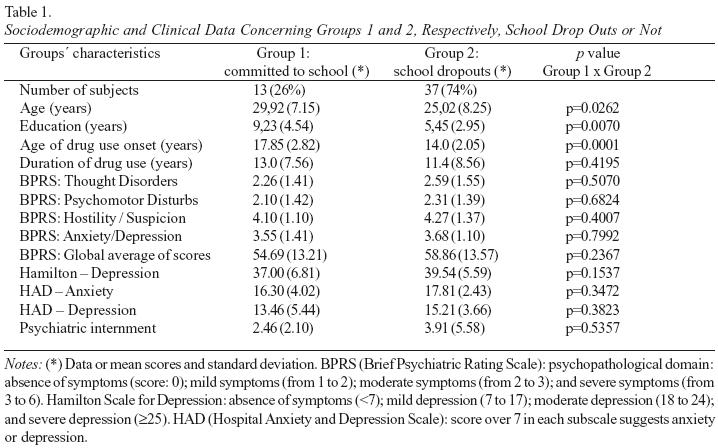

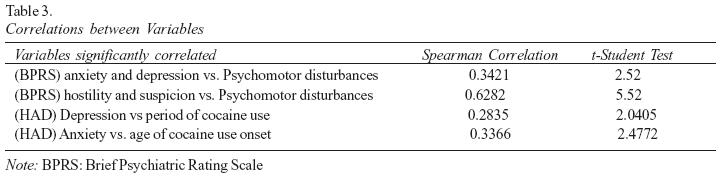

Fifty subjects (42 males and 8 females) with mean age 26.7 (SD=8.03) were studied. In addition to cocaine and crack, used by all subjects, 90% of them were regularly consuming cannabis, and 14% occasionally consumed other substances (benzodiazepines, amphetamines, lysergic acid diethylamidelysergic - LSD, heroin and ecstasy). From the sample, 68% frequently used illegal substances together with alcohol. The average age for the group 1 (29.92 years; SD=7.15) differed significantly in comparison to the group 2 (25.02 years; SD=8.25). (p=0.0262). Duration of drug use varied in all subjects, from one to 20 years (average of 11.8 years; SD=8.35 years). Most subjects (N=40; 80%) initiated drug use between 8 and 17 years of age, while the others (N=10; 20%) between the ages of 18 and 22. The mean period of cocaine use was about 2.2 years, even so it was sufficient to cause severe mental impairment. The Spearman correlation test and the t-Student test displayed a significant association (p<0.05) mainly among some variables. The longer duration of cocaine use was significantly related with severe depressive symptoms according to the Hamilton and HAD scales. Furthermore, severe symptoms of anxiety were significantly associated with early age of cocaine use onset. The statistical analysis also showed a positive significant correlation of psychomotor disturbances with depressive or anxious symptoms and with hostility or suspicion, variables which are from BPRS. The average level of education in the sample was 6.44 years (SD=3.78 years), and 38 subjects (76%) had at maximum of 8 years of education, 10 subjects (20%) had between 9 and 14 years and 2 subjects (4%) had 15 years or more of education.

Only 13 (26%) did not drop out of school due to the use of psychoactive substances (group 1). Regarding the other 37 subjects (74%), a decreased school commitment was verified due to drug abuse (group 2). This interference included important complaints of memory loss, learning difficulty, irregular class attendance, successive failures in school, and definitive dropping out of school. The subjects that dropped out of school presented a significant lower level of education (5.45 years; SD=2.95) compared with those that did not drop out (9.23 years; SD=4.54), (p=0.007).

The age of drug use onset was the variable with greater influence on school dropout rates loss. Thus, the subjects which dropped out of school had begun to use drugs at an early age (average: 14.0 years; SD=2.05), in comparison to the subjects that did not drop out of school and had started the use later on (average: 17.85 years; SD=2.82). There was a significant difference between both groups (p=0.0001). On the other hand, there was no significant difference (p>0.05), between the groups, in relation to the following variables: duration of drug use, scale results, and number of psychiatric internments.

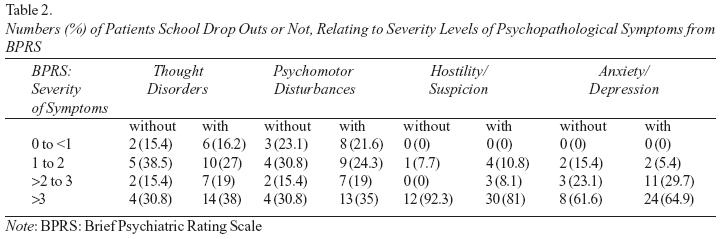

Depression, anxiety, psychotic symptoms, psychomotor agitation and bizarre behavior were the psychopathologic features with high prevalence within both groups. In the Hamilton Scale for Depression, the average score of the total sample was 38.94 (SD=5.88), suggesting severe depressive symptoms. These results were confirmed by HAD, with an average score of the total sample of respectively 17.46 (SD=2.98) for anxiety and 14.52 (SD=4.2) for depression. The scores of both scales were higher than the "cut-off point" for "case" and "non-case". The patients also showed high prevalence of psychotic symptoms by BPRS, such as persecutory auditory and visual hallucinations, paranoid delusions, episodes of psychomotor agitation and aggressiveness. Moreover, in both groups together the average score of this scale, per domain of symptoms, was 3.2 (SD=0.74), and the global average score was 57.78 (SD=13.47). These data suggest severe mental impairment, confirmed through the clinical interview with patients and their relatives or people responsible for them. There was no significant difference between them (p>0.005), since the respective averages of the scales showed very high scores in both groups, confirming the severity mental impairment.

The number of psychiatric internments, which certainly reveal severe mental impairment, showed superior scores in subjects which dropped out of school (group 1: average of 2.5 internments; group 2: average of 3.9 internments). It was impossible to recover the duration of each psychiatric internment as these data were not available in the great majority of patient's records. It is important to highlight, however, that drug abuse spared none of the subjects, committed or not to school, corroborating mental impairment.

Table 1 shows the results of both groups relating: age, education, duration of drug use, age of drug use onset, results from BPRS scales (thought disturbances or psychomotor disturbances, hostility or distrust, anxiety or depression), Hamilton Scale for Depression and HAD (anxiety and depression).

Both groups (committed or not to school) obtained high average scores, such as 2 or 3 concerning each domain of the BPRS, indicating an important clinical severity of the psychopathological symptoms, according to this scale (Table 2 and Table 3).

Discussion

Concerning the simultaneous use of cocaine, crack and other legal or illegal substances, the results of the present study corroborated data from previous studies developed in our country (Carlini et al., 2001; Galduróz et al., 1997; Scivoletto et al., 1996; Silva et al., 2003). An epidemiological investigation developed by Carlini et al. (1993) showed that, from the years 1987 to 1993, cocaine consumption increased significantly, overall among students and street children, mainly in the cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre. In another work, Carlini et al. (2001) verified that school and high school students, in addition to street children had frequently used anticholinergic substances without medical prescription, several of which added to cocaine, barbiturates and amphetamines. According to these authors, these isolated or associated drugs interfere with mental functioning, causing cognitive alterations, behavior disorders, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and psychotic episodes.

All subjects from the present study were using cocaine or crack, together with other psychoactive substances. However, a population study from several Brazilian cities showed a prevalence of cocaine of about 2.3% (Galduróz et al., 2005). Differently from these authors, our investigation was carried out at an Emergency Psychiatric Room, addressing patients with acute mental disorders, including cocaine-dependent individuals, which could partially explain the fact that all the subjects in our study were using this substance.

Subjects with a longer period using cocaine presented more severe depressive symptoms according to Hamilton and HAD scales. To that respect, individuals that had begun to use cocaine at early age presented severer symptoms of anxiety. Young people are probably particularly vulnerable to the deleterious effects of cocaine on mental function and on behavioral self-control. The immaturity of their emotional and cognitive skills may partially explain this vulnerability. The chronic use of cocaine, together with mental variables such as depression, anxiety, psychotic symptoms, and behavior disorders could interact increasing mental impairment.

The subjects who began to use the substance early on (average: 14 years old) showed a more accentuated school dropout rate when compared to those who began the use the substance late on (average: 17.85 years old), with a significant difference between both groups (p=0.0001). These results corroborate the observation of a lower degree of education among the subjects that dropped out of school (average: 5.45 years; SD=2.95) when compared to those who did not (average: 9.23 years; DP=4.54). Previous reports (Florenzano et al., 1993; Tavares et al., 2001) also associated school dropout rates with chemical dependence. On the other hand, university students staying for more time in the school could have more negative attitudes toward the drugs consumption (Bayona et al., 2005), suggesting the possible preventive role of education.

Although the mean level of education of the subjects in the present investigation was 6.4 years, the great majority of them interrupted schooling due to drug use, or presented an impairment of learning faculties during their schooling. Our study confirmed the previous findings from Silva et al. (2003), which demonstrated the interference of the use of multiple substances in school activities. These authors observed a school dropout rate of 44% of the adolescents, a much higher rate than the official data for the Brazilian population (Silva et al., 2003). A partial explanation for this problem could be the deficit caused by cocaine on executive functions (Haster & Garavan, 2004), damaging the ability to set goals and make decisions, in addition to damaging the cognitive processes responsible for staying in school. According to Haster and Garavan (2004) and Verdejo-García et al. (in press) , cocaine-dependent individuals present a significant vulnerability in controlling their impulses, and this phenomenon hampers their ability to set goals and continue their formal education for long period of time.

Furthermore, the act of dropping out of school among cocaine-dependent individuals suggests an interference of this substance with their intellectual development (Cunha et al., 2004). These authors found significant decline of memory, attention span, learning, verbal fluency, and executive functions in cocaine-dependent individuals. Probably, the early age of substance use onset, mainly cocaine, could predispose to higher brain vulnerability and mental disorders. This hypothesis has previously been investigated and suggests that cocaine-dependent individuals present reduction of cerebral blood flow according to the single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and this reduction is associated with cognitive decline (Nicari et al., 2000). Functional images have shown that inhibitory control impairment is associated with decrease activity in the anterior cingulated area during specific tasks in cocaine chronic users (Bolla et al., 2004; Kaufman et al., 2003). In addition, cocaine-dependent individuals tend to present structural abnormalities on the anterior cingulated area and on the prefrontal cortex regions (Matochik et al., 2003), and these disorders contribute to executive dysfunctions (Bolla et al., 2004). Furthermore, the chronic cocaine-dependent individuals present changes in the neurotransmitter system with a lowered synaptic density of both serotonin and dopamine in the brain (Ghitza et al., 2007). Certainly, decreased serotonin and dopamine transmission may precipitate affective disorders. In mental impairment, the decreased synaptic serotonin particularly contributes to irritability, obsessive thoughts, and loss of impulse control, while decreased synaptic dopamine leads to reward dysfunction such as anhedonia (Ghitza et al., 2007), and most probably to psychotic symptoms.

Other psychopathological disturbances identified by the present study are compatible with the data originating from other studies. Watkins et al. (2004) verified high rates of psychiatric comorbidities among drug addicts, such as depression and anxiety, including suicide attempts among students (Wilcox et al., 2004; Booth et al., 2005). According to Voros et al. (2005), cocaine-dependents, which had attempted suicide, usually, had higher scores in scales measuring anxiety, depression, and impulsivity in addition a significant low self-esteem. Our results confirmed the high scores on items of depression scales (Hamilton depression and HAD) and on BPRS items concerning self-destructive feelings, in both groups school dropouts or not.

The present study showed high severity of psychopathological symptoms identified by the BPRS, indicating mental impairment, confirmed by another work (Hervás et al., 2000). In cocaine-dependent individuals, these authors identified psychotic symptoms characterized by paranoid ideas and delusions, reaching a prevalence of 95% of patients, and hallucinations in 63% of them (Hervás et al., 2000). We also reinforced previous reports (Thirthalli & Benegal, 2006) asserting a substantial proportion of psychosis among drug-addicts. These authors displayed strong evidence that substance abuse, mainly cocaine, is associated with a greater risk for psychosis and for their causative role in the development of this psychopathological condition (Thirthalli & Benegal, 2006). Our study confirmed the results of these authors regarding the influence of severity, duration and early age of drug use onset on vulnerability to mental impairment. This psychopathological state in substance-dependent individuals is characterized by poor self-esteem, antisocial behavior, depressive mood, suicide thoughts, anxiety, psychosis, as well as cognitive impairment (Haster & Garavan, 2004; Kalayasiri et al., 2006; Thirthalli & Benegal, 2006; Ghitza et al., 2007; Kokkevi et al., 2007).

Within a student population, Moeller et al. (2002) also observed personality disorders associated with drug use, and Giancola (2002) suggested that psycho actives make depressive disorders and mental or behavioral disorganization more serious. Dissolution of family and social links and irregularity in professional activities constitute other ingredients detected in the lives of psychoactive substance users, according to the present study and according to previous investigations (Moeller et al., 2002). Finally, the school have an important role in general attitudes of students toward the prevention of drugs use, mainly organizing structured and systematic programs aiming to discuss the implications of chemical dependence (Bayona et al., 2005).

The present work has several limitations. The information regarding the use of cocaine or crack and other substances were obtained through the subjects, their relatives or people responsible for them. It was not possible to verify the laboratory dosages of the psychoactive substance due to operational difficulties encountered during the research. Furthermore, it was not possible to obtain information regarding the cognitive and academic performance of the subjects from their respective schools. New researches would be necessary in order to verify if chemical abuse, confirmed by laboratory investigation, interferes with the school commitment, as well as with mental and behavioral conditions.

In this study, chemical-dependent individuals who had started to use drugs at an early age presented significantly higher school dropout rates when compared with those who started the use drugs later on. Psychotic symptoms, thoughts and behavior disorganization, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and detriment of family or professional links were severe phenomena within both groups. The role of schools in recognizing and developing adequate and effective programs towards the prevention drug dependence is very urgent. We suggest an acute awareness on behalf of the education professionals when considering preventive actions regarding the use of illegal psychoactive substances; and that in addition, they should be particularly attentive to signs of risk factors and indications of vulnerable lifestyles in schools.

References

APA (American Psychiatric Association). (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Bayona JA, Hurtado C, Ruiz IR, Hoyos A, & Gantiva CA. (2005). Actitudes frente a la venta y el consumo de sustancias psicoactivas al interior de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 39(1): 159-168. [ Links ]

Bolla, K.I., Funderburk, F.R., & Cadet, J.L. (2000). Differential effects of cocaine and cocaine alcohol on neurocognitive performance. Neurology, 54, 2285-2292. [ Links ]

Bolla, K.I., Ernst, J, Mouratidis, M., Matochik, J.A., Contoreggi, C., Kurian, V., Cadet, J.L., Kimes, A.S., Eldreth, D., & London, E.D. (2001). Reduced cerebral blood flow in anterior cingulated cortex (ACC) during Stroop performance in chronic cocaine users. Human Brain Mapping, 13, 772. [ Links ]

Bolla, K., I., Ernst, M., Kiehl, K., Mouratidis, M., Eldreth, D., & Contoreggi, C. (2004). Prefrontal cortical dysfunction in abstinent cocaine abusers. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 16, 456-464. [ Links ]

Booth, B.M., Weber, J.E., Walton, M.A. Cunningham, R.M., Massey, L., Thrush, C.R., & Maio, R.F. (2005). Characteristics of cocaine users presenting to an emergency department chest pain observation unit. Academic and Emergency Medicine, 12, 329-337. [ Links ]

Botega, N.J., Bio, M.R., Zomignani, M.A., Garcia Jr, C., & Pereira, W.A. (1995). Mood disorders among medical in-patients: a validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HAD). Revista de Saúde Pública, 29,359-363. [ Links ]

Carlini, E.A., Nappo, S.A., & Galduroz, J.C.F. (1993). A cocaína no Brasil ao longo dos últimos anos. Revista da Associação Brasileira de Psiquiatria -Associação de Psiquiatria para a América Latina, 15:121-127. [ Links ]

Carlini, E.A., Goldeiróz, J.C.F., Noto, A.R., & Nappo, A.S. (2001). I Levantamento domiciliar sobre o uso de drogas psicotrópicas no Brasil. São Paulo: (CEBRID) Centro Brasileiro de Informações sobre Drogas Psicotrópicas. Departamento de Psicobiologia. Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Cunha, P.J., Nicastri, S., Gomes, L.P., Moino, R.M., & Peluso M.A. (2004). Alterações neuropsicológicas de cocaína / crack internados: dados preliminares. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 26, 103-106. [ Links ]

Del Porto, J.A. (1989). Aspectos gerais das escalas para avaliação de depressão. In Escalas de Avaliação para Monitorização de Tratamento com Psicofármacos (pp. 93-100). São Paulo: Centro de Pesquisa em Psicobiologia Clínica do Departamento de Psicobiologia da Escola Paulista de Medicina. [ Links ]

Di Sclafani, V., Tolou-Shams, M., Price, L.J., & Fein, G. (2002). Neuropsychological performance of individuals dependent on crack-cocaine, or crack-cocaine and alcohol, at 6 weeks and 6 months of abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 66, 161-171. [ Links ]

Elkis, H., Alves. T, Eizenman, I.B., Henna, N.J., Oliveira, J.R.C., & Melo, M.F. (2000). BPRS Ancorada (BPRS-A): diretrizes de uso, estrutura fatorial e confiabilidade da versão em português. In C. Gorenstein, L.H.S.G. Andrade, & A.W. Zuardi (Eds.), Escalas de Avaliação Clínica em Psiquiatria e Psicofarmacologia (pp. 199-206). São Paulo: Lemos. [ Links ]

Falck, R.S., Wang, J., Siegal, H.A., & Carlson, R.G. (2004). The prevalence of psychiatric disorder among a community sample of crack cocaine users: an exploratory study with practical implications. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 92, 503-507. [ Links ]

Fillmore, M.T., & Rush, C.R. (2002). Impaired inhibitory control of behavior in chronic cocaine users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 66, 265-273. [ Links ]

Florenzan, R., Pino, P., & Marchandon, A. (1993). Risk behavior in adolescent students in Santiago de Chile. Revista Medica Chilena., 121, 462-469. [ Links ]

Galduroz, J.C.F., Noto, A.R., & Carlini, E.A. (1997). IV Levantamento sobre o uso de drogas entre estudantes de 1º e 2º graus em 10 capitais brasileiras. São Paulo: [CEBRID] Centro Brasileiro de Informações sobre Drogas Psicotrópicas, Departamento de Psicobiologia, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal Paulista.

Galduroz, J.C., Noto, A.R., Nappo, S.A., & Carlini, E.A. (2005). Household survey on drug overuse in Brazil: study involving the 107 major cities of the country. Addict Behavior, 30, 545-556. [ Links ]

Ghitza, U.E., Rothman, R.B., Gorelick, D.A., Henningfield, J.E., & Braumann, M.H. (2007). Serotonergic responsiveness in human cocaine users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86, 207-213. [ Links ]

Giancola, P.R. (2002). Irritability, acute alcohol consumption and aggressive behavior in men and women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 68, 263-274. [ Links ]

Goldstein, R.Z., Leskovjan, A.C., Hoff, A.L., Hitzemann, R., Bashan, F., & Khalsa, S. (2004). Severity of neuropsychological impairment in cocaine and alcohol addiction: association with metabolism in the prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychologia, 42, 1447-1458. [ Links ]

Hamilton, M. (1960). Rating Scale for Depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23, 56-62. [ Links ]

Hester, R., & Garavan, H. (2004). Executive dysfunction in cocaine addiction: evidence for discordant frontal, cingulate, and cerebellar activity. Journal of Neurosicience, 24(49), 11017-11022. [ Links ]

Hervás, S.E., Gradoli, T.V., & Gallús, M.E. (2000). Evaluación psicopatológica de pacientes dependentes de cocaína. Atencion Primaria, 26, 319-322. [ Links ]

Hoff, A.I., Riordan, H., Morris, L., Cestaro, V., Weineke, M., Alpert, R., Wang, G.J., & Volkow, N.D. (1996). Effects of crack cocaine on neurocognitive function. Psychiatry Research, 60, 167-176. [ Links ]

Kalayasiri, R., Kranzler, H.R., Weiss, R., Brady, K., Gueorguiva, R., Panhauysen, C., Yang, B.Z., Ferrer, L., Gelenter, J., & Malison R.T. (2006). Risk factors for cocaine-induced paranoia in cocaine dependent sibling pairs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 84(1), 77-84. [ Links ]

Kaufman, J.N. Ross, T.J., Stein, E.A., & Garavan, H. (2003). Cingulate hypoactivity in cocaine users during a GO-NOGO task as revealed by event-related fMRI. Journal of Neurosciences, 23, 7839-7843. [ Links ]

Kokkevi, A., Richardson, C., Florescu, S., Kuzman, M., & Stergar, E. (2007). Psychosocial correlates of substance use in adolescence: a cross-national study in six European countries. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(1), 67-74. [ Links ]

Matochik, J.A., London, E.D., Eldreth, D.A., Cadet, J.L., & Bolla, K.I. (2003). Frontal cortical tissue composition in abstinent cocaine abusers: a magnetic resonance imaging study. NeuroImage, 19, 1095-1102. [ Links ]

Moeller, F.G., Dougherty, D.M., Barrat, E.S., Oderinde, V., Mathias, C.W., Harper, R.A., & Swann, A.C. (2002). Increased impulsivity in cocaine dependent subjects independent of antisocial personality disorder and aggression. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 68, 105-111. [ Links ]

Moreno, R.A., & Moreno, D.H. (2000). Escalas de avaliação para depressão de Hamilton (HAM-D) e Montgomery-Asberg (MADRS). In C. Gorenstein, L.H.S.G. Andrade, & A.W. Zuardi Escalas de Avaliação Clínica em Psiquiatria e Psicofarmacologia (pp.71-87). São Paulo: Lemos. [ Links ]

Nappo, S.A., Galduroz, J.C.F., & Noto, A.R. (1994), Uso de "crack" em São Paulo: um fenômeno emergente? Revista da Associação Brasileira de Psiquiatria - Associação de Psiquiatria para a América Latina, 16, 75-83. [ Links ]

Nicastri, S., Buchpiguel, C.A., & Andrade, A.G. (2000). Anormalidades de fluxo sanguíneo cerebral em indivíduos dependentes de cocaína. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 22, 42-50. [ Links ]

Overall, J.E., & Gorham, D.R. (1962). The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychology Report, 10, 799-812. [ Links ]

Pace-Schott, E.F., Stickgold, R., Muzur, A., Wigren, P.E., Ward, A.S., Hart, C.L., Walker, M., Edgar, C., & Hobson, J.A. (2005). Cognitive performance by humans during a smoked cocaine binge-abstinence cycle. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Overuse, 31, 571-591. [ Links ]

Pope, H.G., & Yurgelun-Todd, D. (1996). The residual cognitive effects of heavy marijuana use in college students. Journal of American Medical Association, 275, 521-527. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, M., Marques, A.C.P.R., Laranjeira, R., Alves, H.N.P., Araújo, M.R., Baltieri, D.A., et al. (2005). Abuso e dependência da maconha. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, 51, 78-88. [ Links ]

Rimsza, M.E., & Moses, K.S. (2005). Substance overuse on the college campus. Pediatric Clinic of North America, 52, 307-319. [ Links ]

Robinson, J.E., Heaton, R.K., & O'Malley, S.S. (1999). Neuropsychological functioning in cocaine overusers with and without alcohol dependence. International Neuropsychology Society, 5,10-19. [ Links ]

Romano, F., & Elkis, H. (1966). Tradução e adaptação de um instrumento de avaliação psicopatológica das psicoses: a escala breve de avaliação psiquiátrica - versão ancorada (BPRS-A). Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 45, 43-49. [ Links ]

Rosselli, M., Ardila, A., Lubomski, M., Murray, S., & King, K. (2001). Personality profile and neuropsychological test performance in chronic cocaine-overusers. International Journal of Neurosciences, 110, 55-72. [ Links ]

Scivoletto, S., Henriques, S.G., & Andrade, A.G. (1966). A progressão do consumo de drogas entre adolescentes que procuram tratamento. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 4, 201-207. [ Links ]

Silva, .VA., Aguiar, A.S., Felix, F., Rebello, G.P., Andrade, R.C., & Mattos, H.M. (2003). Brazilian study on substance misuse in adolescents: associated factors and adherence to treatment. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 25, 133-138. [ Links ]

Tavares, B.F., Béria, J.U., & Lima, M.S. (2001). Prevalência do uso de drogas e desempenho escolar entre adolescentes (Drug use prevalence and school performance among teenagers). Revista de Saúde Pública, 35, 150-158. [ Links ]

Thirthalli, J., & Benegal, V. (2006). Psychosis among substance users. Current Opinion Psychiatry, 19(3), 239-245. [ Links ]

Verdejo-García, A.J., Perales, J.C., & Pérez-García, M. (in press). Cognitive impulsivity in cocaine and heroin polysubstance abusers. Addictive Behaviors. [ Links ]

Voros, V., Fekete, S., Hewitt, A., & Osvath, P. (2005). Suicidal behavior in adolescents psychopathology and addictive commorbidity. Neuropsychopharmacology in Hungry, 7(2), 66-71. [ Links ]

Watkins, K.E., Hunter, S.B., Wenzel, S.L., Tu, W., Paddock, S.M., Griffin, A., et al. (2004). Prevalence and characteristics of clients with co-occurring disorders in outpatient substance overuse treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Overuse, 30, 749-764. [ Links ]

Wert, R.C., & Raulin, M.L. (1986). The chronic cerebral effects of cannabis use: psychological findings and conclusions. International Journal of Addiction, 21, 629-642. [ Links ]

Wilcox, H.C., Conner. K.R., & Caine, E.D. (1983). Association of alcohol and drug disorders and completed suicide: an empirical review of cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 76(Suppl), 11-19. [ Links ]

Zigmond, A.S., & Snaith, R.P. (1983).The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinava, 67, 361-370. [ Links ]

Received: 16/08/2006

Accepted: 08/05/2007

1 Endereço: Instituto de Biociências - Departamento de Educação. Caixa Postal: 199, 13.506-900, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil. E-mail: fstella@rc.unesp.br

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI