Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

versión impresa ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. v.43 n.1 Porto Alegre abr. 2009

Narrative production of older adults: investigating a possible pragmatic change

Producción narrativa de adultos mayores: investigando un posible cambio pragmático

Lenisa BrandãoI; Maria Alice de Mattos Pimenta ParenteII,1

IUniversidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

IIUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brasil

ABSTRACT

This study investigated the possible pragmatic change concerning the narrative production of older adults. Brazilian young and older adults residing in Porto Alegre/BR were instructed to tell personal and fictitious stories. Propositions of their discourse were analyzed in terms of relevance, subjectivity and repetition. Older adults presented a greater proportion of indirectly relevant propositions, expressed more subjective content and repeated more propositions than younger adults. Older adults also demonstrated preference for personal narratives. Evidence supported the pragmatic change hypotheses concerning the discourse production of older adults.

Keywords: Older adults; Pragmatic change; Discourse production; Narrative, Language.

RESUMEN

Este estudio ha investigado el posible cambio pragmático en la producción narrativa de adultos mayores. Se instruyó a adultos jóvenes y mayores residentes de Porto Alegre/BR a que contasen historias personales y ficticias. Las proposiciones de sus discursos fueron analizadas en términos de relevancia, subjetividad y repetición. Adultos mayores presentaron una proporción mayor de proposiciones indirectamente relevantes, expresaron más proposiciones subjetivas y repitieron más ideas que adultos jóvenes. Adultos mayores también demostraron preferencia por narraciones personales. Las evidencias apoyaron la hipótesis de cambio pragmático en la producción narrativa de adultos mayores.

Palabras clave: Adultos mayores; Cambio pragmático; Producción discursiva; Narración; Lenguaje.

Literature of the last decades demonstrates the controversy between research on language production of older adults, particularly in studies that investigate the presence of "off-topic verbosity" (OTV). OTV studies represent a considerable contribution to the investigation of older adults' discourse. This characteristic of speech production is defined by Arbuckle and Gold (1993) as extended speech that lacks coherence. The studies have been divided in two different paradigms, one that defends the idea of an age-related decline in language production, associated to an inhibitory deficit, and the other which argues that age-related changes in narrative production reflect communicative intentions in discourse. These propositions have been studied by investigations that examine discourse production from different theoretical and methodological bases. Non of these paradigms is explicitly related to a discourse processing theory of coherence.

The prevailing explanation for OTV in older adults' discourse is the Inhibition Deficit Hypothesis, which posits that the lack of coherence in the speech of a number of older adults is related to a general problem for inhibiting irrelevant stimuli (Arbuckle & Gold, 1993; Gold, Andres, Arbuckle, & Zieren, 1993; Gold & Arbuckle, 1995). These authors have concentrated in selected samples with OTV, showing a correlation between high OTV levels and low performance on inhibition related measures such as the Trail Making Test (Reitan & Davison, 1974), the Stroop test (Stroop, 1935; Trenerry, Crosson, DeBoe, & Leber, 1989) and the Verbal Fluency task (Benton & Hamsher, 1976). Authors who support the inhibition hypothesis state that OTV is present in a small number of older adults. However, these studies seem to disregard discourse changes which may be present in the majority of the older adult population. Some authors, such as Juncos-Rabadan, Pereiro, and Rodriguez (2005) have not taken a position of explicit support to the inhibition hypothesis. These authors recognize that changes in social situation experienced by older adults may create a greater need for communication that, in turn, drives pragmatic differences consisting in greater talkativeness. However, their findings on a reduction of relevance in narratives are interpreted as resulting from the cognitive decline of executive functions, along with the finding that verbal capacity improves content and cohesion. Although vocabulary is mentioned as having a protective roll, the idea that discourse declines in older age is implicit in the arguments.

An alternative account about the discourse production of older adults has been provided by the Pragmatic Change Hypothesis, which considers the impact of the speaker's intentions on communication. Following this point of view, the speech style considered off-topic does not relate to the cognitive competence of the speaker, but to his or her social context and identity. Older adults value their narratives as social interaction opportunities for reminiscence and establishment of identity (Boden & Bielby, 1983; Burke, 1997). Relying on the pragmatic approach, James, Burke, Austin and Hulme (1998) compared the performance of older and younger adults in the production of personal narrative and picture description. Their results demonstrated age-related increase in OTV levels in personal narrative, which is a discourse gender that emphasizes the exposition of life events. In turn, picture descriptions, which provided more objective communication situations, presented lower OTV scores. In addition, older adults' narratives were rated by younger and older adults as more interesting, informative, and simply as better stories. Although older adults produced more OTV, their narratives appeared to have greater communicative value than that of younger adults, suggesting that there is not a decrement in the quality of older adults' discourse.

The Pragmatic Change Hypothesis related to OTV, has also been held by authors such as Burke (1997), who has expressed a critical stance towards the Inhibition Deficit Hypothesis, pointing out that communicative intention is determinant in discourse style. Many authors that maintain this position have shown that differences between older and younger adults' narratives can be explained by differences in terms of what is represented as relevant by the speaker and his or her social identity.

In a study that did not focus on OTV, Korolija (2000) found that conversations amongst older adults present different coherence-inducing strategies. Repetition was pointed by this author as a principle of organization. Unconventional topical flow, was explained as a strive of the older adult speaker for aspects of themes that seem to be considered more interesting.

According with the ideas exposed by Bruner (1999), in a theoretical article about older adults' narratives, older adults do not decline in narrative production. In contrary, according to Bruner, they might even evolve in narrative ability. Bruner (1999) considers that the climax of stories is related to the attention given to the "mental scenery", which includes emotional states, moral statements, perspectives and motives of the characters. These aspects seem to play an important role in the narrative of older subjects. The "mental scenery", which is considered conventionally as non-objective, indirectly related information, is responsible for painting the protagonists as heroes or clowns. In the case of stories intended to tell funny episodes, generally it is the "mental scenery" that will make the narrative seem funny. In the same way, suspense stories will only provoke expectation and excitement in the presence of the "mental scenery".

Randall (1999) suggests that the "internal narrative" seems to continue expanding in older age, and that there is no reduction of the interpretative capacity of one's life story. In fact, older adults appear to be interested in making sense of life experiences, expressing a subjective appreciation of events and describing emotional states, more than younger adults seem to do. This may be due to the greater amount of personal experience and to the way that older adults may represent themselves as communicative actors in context.

In this study, we consider the Pragmatic Change Hypothesis in the light of the discussions about coherence and context raised by van Dijk (1980/1996a, 1998) in his discourse processing model. This psycholinguistic basis will orient our approach to mental models of the communication context and the nature of what is considered irrelevant speech.

Mental models are constructed based on personal experience stored in episodic memory. They contain not only relevant knowledge about the setting and acts that take place in a narrative, but also the personal opinion and beliefs of the speaker in relation to the particular event being told. Differences in thematic organization may be due to differences in mental models. Participants of the same event will have different representations of the event, and may even disagree about what should be considered relevant. Opinions about events vary largely and can influence the expression of relevance in narrative discourse (van Dijk, 2001). The selection of a certain message implicates mental operations such as the elaboration of pragmatic goals or communicative intentions that consider the context and the knowledge of the other participants. These processes rely on the existence of the context mental model. According to van Dijk (2003), context models are mental representations of what language users consider relevant in the communication situation, including the assumed mental model of the other participants and social rules of the particular context.

According to van Dijk (1980/1996a, 1998), a coherent discourse contains relations of differences and changes. The speaker provides new information linked to given information. Thus, new information needs to be linked to previous information and also to the global macroproposition in direct and indirect manners (van Dijk, 1998). Therefore, it can be inferred that a coherent narrative is constituted by relevant and indirectly rele-vant propositions. Consequently, the presence of indirectly relevant propositions should not be considered off-topic signs of decrement in coherence. Normal discourse can contain off-topic propositions and still maintain coherence through the use of particular strategies, such as topic change indicators and parenthetic explanations. These production strategies demonstrate the intention of maintaining coherence in narrative. Thus, in the case of the presence of irrelevant speech, van Dijk (1983/1996b) clarifies that the expression of information considered irrelevant, cannot be explained exclusively by a cognitive deficit. When irrelevant ideas are expressed, it is important to consider that relevance rules can be broken due to contextual reasons. The speaker expresses his or her ideas not as a function of the real world, but rather as a function of his or her own mental model of the situation and of the context of communication (van Dijk, 1983/1996b).

The main goal of this study was to investigate coherence production in older adults' narrative discourse. The Pragmatic Change Hypothesis was verified through a pragmatic theory of discourse processing, which takes into account the propositional organization of discourse, and the use of coherence strategies. The specific goals of the study consisted in: (a) verifying the possible differences between age groups and narrative types in terms of discourse relevance; and (b) comparing the groups concerning the total number of propositions, subjective remarks and repeated propositions.

Hypotheses concerning older adults' narrative production proposed that it would be less focused to the topic and more subjective. A greater number of total propositions was also expected. These expected findings could be explained by either of the two alternative hypotheses (inhibition vs. pragmatic change). The presence of a greater proportion of subjective remarks would agree with this hypothesis, except if a greater number of these subjective remarks were to be off-topic, signaling a deficit in coherence related to the expression of irrelevant subjective thoughts. Preference for personal reports in the fictitious stories, i.e., if the elderly were to demonstrate a preference for creating stories in which they were protagonists, this would support the pragmatic change hypothesis. In opposition, if no difference in this aspect was to be observed, the idea that older adults have different communication goals than younger adults would not be confirmed.

Method

Participants

The participants of this study were volunteer young and older adults residing in Porto Alegre/BR. The sample of young adults ranged from 20 to 30 years old, and the sample of older adults ranged from 65 to 75 years old. The age of the participants in the older adult sample is justified by standards of the World Health Organization, which considers that the older adult population in developing countries is composed by those above 60 years old. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics ([IBGE], 2002) also adopts this starting age for statistic measures of the older adult population. All the participants received information about the study and signed a letter of consent that explained the purpose of the study and that assured identity preservation.

A social and cultural interview was used to describe each group. This subjective interview was not only related to cultural and social habits, but also contained questions related to health, in order to exclude individuals with psychiatric and neurological disorders. Reported social characteristics of each group of participants showed that the majority of both younger and older adults did not live alone (only 10% of younger adults and 20% of older adults lived alone), a great number of individuals received visitors in a regular basis (65% of younger adults in a range from everyday to once a week, and 70% of older adults in a range of more than once a week to once a week), a considerable number of subjects participated in social activities related to sports or religion with some regularity (50% of younger adults participated in social activities related to sports, and 75% of older adults participated in religious groups), and the majority of both groups reported that their non-domestic activities involved socialization (90% of the younger adults and 80% of the older adults). Concerning cultural aspects, younger and older adults had studied at least 13 years, and presented reading habits such as reading magazines (85% of young adults and 80% of the old adults read from once a week to everyday), and news papers (90% of young adults and 100% of old adults).

Older adults were screened using the Mini Mental State Exam ([MMSE], Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975; Chaves & Izquierdo, 1992) and the Yesavage Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (Yesavage, Brink, Rose, & Lurn, 1983) to exclude individuals with cognitive impairment and depression. Two groups of 20 young and 20 older adults with the equivalent of complete high school education were designated to participate in the investigation. All subjects were reported being in good health, with no history of speech, language or hearing problems.

Procedures

Both groups underwent a one hour session of topic-directed interview with one of the authors in a quiet room. Participants were assessed individually. All interviews were audio taped, and all interviewees knew that they were being taped. After a small conversation to facilitate interaction, the participants were asked to tell a personal story about a funny episode that happened in their life. After the personal story, they were instructed to create and tell a fictitious story. In this second discourse task, two suspense topics were given as options: "hearing the noise of foot steps at night" or "the appearance of a strange light". Comedy and suspense themes were chosen due to evidence of subject motivation and narrative generation suggested by literature (Jose & Brewer, 1984; Murray, 1988). In both narratives, the subjects were encouraged to express the story freely, without interruptions of the examiner, who provided only contextual communication responses (i.e. "umhum", "yes"...) and repeated instructions when necessary. Each interview was transcribed in its entirety, both orthographically and verbatim. Contextual notes, such as important gestures and other nonverbal behaviors that affected story comprehension were reported. Unintelligible utterances were excluded from the analysis.

Reliability of Discourse Analysis

Three judges consisting in two Psychology students and one Speech Therapist were trained to segment discourse into propositions (one predicate plus to or more arguments) and to judge the semantic content of propositions in terms of relevance, subjectivity and repetition. To assure reliability of the analysis, inter-judge agreement was verified in the entire corpus. Agreement between judges was calculated using correlation coefficient test Tau de Kendall. The lowest agreement found was 77% (indirectly relevant propositions) and the highest agreement found was 92% for total of propositions.

Discourse Analysis

Propositions were classified into the following categories:

Relevant Propositions. Propositions that present direct relation to the topic. For example, propositions informing about the scenario, characters and their actions, important characteristics of the scenario and its protagonists; and subjective comments essential for story comprehension.

Indirectly Relevant Propositions. Propositions that are not essential for story comprehension, related to relevant propositions; for example, propositions that inform about unnecessary features of the scenario and its characters, feelings of the narrator towards the facts and characters, facts that happened as a cause or a consequence of the story, non relevant subjective comments about protagonists, the scenario and relevant facts.

Irrelevant Propositions. Propositions that presen no cause, comparison, specification or meaning relations to the suggested topic; for example, propositions that inform about the present state of mind of the narrator, personal activities of the narrator, religion, opinions related to other themes, reflections about life, reference of people that do not participate in the story.

Subjective Remarks. Propositions expressing personal opinions and feelings of the narrator; for example, "I think this is a wonderful story", "I am always playing tricks on people, that's why I have this story". The total number of subjective remarks was counted, as well as classified in terms of relevance (relevant, indirectly relevant, and irrelevant).

Repetition of Propositions. Propositions that appeared more than once in the same discourse. The total number of repetitions was counted.

Results

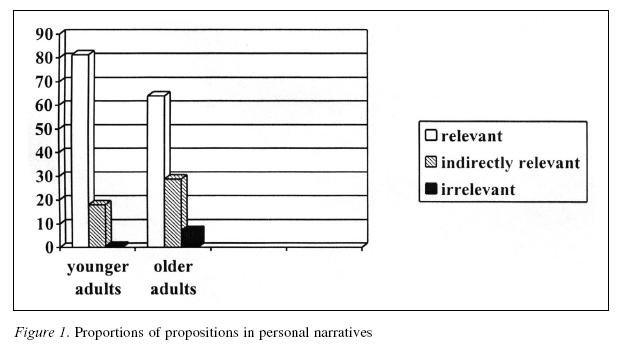

As shown in Figure 1, the Mann-Whitney test used for comparison between proportions showed that young adults expressed a greater proportion of relevant propositions, presenting in their discourse 81,3 of relevant propositions, while older adults, presented a proportion of 63,9 of relevant propositions in personal narratives (U=2,64; p< .007). In turn, older adults presented a greater proportion of indirectly relevant propositions, presenting 28,8 of these propositions in their discourse, while young adults presented a proportion of 18 (U=-2,04; p< .04). Although older adults appeared to have a tendency to express more irrelevant information in personal stories, the difference between young and older adults concerning the emission of these propositions was not significant.

The same tendencies were observed in the fictitious stories produced, but the differences in relation to the proportion of propositions according to their relevance were not significant. Although the theoretical position adopted disagrees with the idea that irrelevant and indirectly relevant propositions have the same role in discourse coherence, a non-relevant proportion was created, summing irrelevant and indirectly relevant propositions together to enable comparisons with findings of other studies. The results showed that older adults expressed 36,1 non-relevant propositions, which is significantly more than did younger adults (18,7) in personal narratives (U=102,5; p< .01).

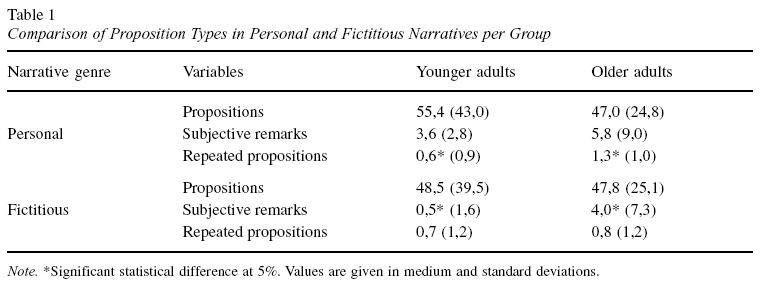

Comparing personal narratives, again differences between the young and the older adult groups appeared concerning the presence of repeated propositions, as shown in Table 1. This variable was measured in the form of absolute numbers of total repeated propositions, also using the Mann-Whitney test. Older adults repeated more propositions then young adults, presenting a medium of 1,3 repeated propositions, while young adults presented a medium of 0,6 repetitions in personal narratives (U=-2,27, p< .01). Table 1 also demonstrates that the same test with absolute numbers showed that the two samples also presented significant differences in fictitious narratives. Older adults expressed a greater amount of subjective remarks, emitting a medium of 4,0 subjective remarks, while young adults presented a medium of only 0,5 subjective remarks in fictitious narratives (U=-2,41, p< .05).

In both types of narratives, no difference was observed in the total number of propositions produced by the two groups. However, when the samples were summed together, the Wilcoxon test showed that personal narratives presented more subjective remarks than fictitious narratives. Personal narratives presented a medium of 4,7 subjective remarks, while fictitious narratives presented a medium of only 2,3 subjective remarks (z=-3,45; p< .001).

Differently than young adults, older adults pre-ferred to produce fictitious stories in which they were protagonists. The chisquare test showed that 80% of the fictitious stories produced by older adults were personal reports, while 45% of the young adults' fictitious stories were personal reports, showing that young adults did not express preference for this narrative style.

Discussion

In personal narratives, the finding that young adults expressed a greater proportion of relevant propositions than older adults and that older adults presented a greater proportion of indirectly relevant propositions seems to indicate that, compared to younger adults, older adults were less focused on the proposed theme. This finding confirmed the initial hypothesis of the study. Irrelevant speech did not differ significantly between the groups. This data shows that older adults' discourse was not less coherent than young adults' discourse.

When summed, indirectly relevant and irrelevant propositions (non-relevant proportion) were in greater number in older adults' discourse. These results could be interpreted as an agreement with studies about off-topic verbosity that suggest that older adults tend to produce less coherent discourses than younger adults (Arbuckle & Gold, 1993; Arbuckle, Nohara-Le Clair, & Pushkar, 2000; Gold, Andres, Arbuckle, & Schwartzman, 1988; Gold et al., 1993; Gold & Arbuckle, 1995). However, caution in the interpretation of this data is necessary. According to the analysis adopted in the present study, indirectly relevant propositions do not alone promote incoherence in discourse (van Dijk, 1998). In fact, the expression of indirectly relevant information is consi-dered essential for the construction of a well-formed narrative, providing tension, and presenting the "mental scenery" of the story (Bruner, 1997). It was the number of irrelevant propositions that represented the "off-topic" score related to incoherence in this study. In this mea-sure, older and younger adults' discourse did not differ significantly.

The absence of differences concerning the expression of irrelevant propositions contrasts with findings of the studies done by Gold and colleagues (Arbuckle & Gold, 1993; Arbuckle et al., 2000; Gold et al., 1988; Gold et al., 1993; Gold & Arbuckle, 1995) about OTV. This finding is due to differences in the classification analysis adopted for distinguishing indirect topic related propositions and irrelevant topic propositions. Because of the theoretical basis adopted, the present study did not primarily add up irrelevant and indirectly relevant elements to form the off-topic score, as done in those studies.

Concerning the amount of repetitions expressed by each group, repetitions produced by older adults were not irrelevant propositions. Therefore, these repetitions may indicate the use of a strategy to provide time for the access of new information in memory. Repetitions may also represent emphasis to certain elements that have a greater appeal to the narrator. The presence of repetitions in older adults' discourse agrees with the results of Korolija (2000), which investigated coherence strategies among an aged group. This author reported that older adults did not express off-topic information, but their narratives seemed not to progress in actions. Korolija (2000) argued that repetitions can demonstrate a strive for aspects of themes that seem more interesting to older adults, because the expression of actions is not their main communicative goal. Additionally, repetitions may appear as forms of self-correction in discourse production, which may demonstrate the use of on-line meta-discursive strategies (Mansur, 1991).

In fictitious narratives, no differences were observed in the proportion of propositions according to relevance. This result suggests that personal narratives appear to evoke more indirectly relevant propositions in general, but mostly in older adults' narratives. This finding agrees with James et al. (1998), who compared the production of personal stories and the descriptive discourse of young and older adults. A greater number of indirectly relevant information appeared in personal narratives than in descriptions, suggesting that subjects access more indirectly relevant information from episodic memory when they produce a personal story than in other discourse genres.

A tendency of both groups to produce more indirect and subjective content in personal narratives was observed. Consequently, only in fictitious stories the amount of subjective information in older adults' productions exceeded that of young adults' stories. The greater amount of subjective content in older adults' stories again suggested that they intended to create stories guided by their emotions and opinions. They also preferred to create stories which were personal, i.e., the narrator performed the role of the main character. As Randall (1999) pointed out, it seems that there is no reduction of the interpretative capacity of one's life story in older age. In fact, older adults appear to be more interested in making a subjective sense of personal experiences. The differences between groups appeared again to be a difference in communicative intention and identity, as a sign that older adults indeed have different pragmatic goals. This data agrees with the finding of Parente, Capuano and Nespoulous (1999) that older adults tend to activate their mental models to a greater extent in the production of stories than do young adults.

In both types of narratives, no significant difference was observed in the total number of propositions produced by the two groups. This result indicates that the older adults participating in this study did not present talkativeness compared to young adults. Considering these results, it becomes evident that the older adults of this study did not present off-topic verbosity (OTV). This finding was not a surprise, as even OTV studies which support the inhibition hypothesis (Arbuckle et al., 2000; Gold et al., 1988; Gold et al., 1993; Gold & Arbuckle, 1995) show evidence that this discourse feature appears only in a small portion of the older adult population and it can be influenced by variables such as anxiety and low satisfaction to social support, which were not features of the older adult sample of this study. The semi-structured interview used in order to access social and cultural information about the older adults' sample showed that the majority of older adults described themselves as having an active social and cultural life. Although this study did not use psychosocial validated instruments, the subjective information given by the interviewees indicates that this particular group does not have the social and cultural features which might be associated with OTV. Personality styles of older adults (for a review, see Krzemien, 2007) were also not accounted for in this study. Additionally, the small number of participants in our sample does not allow any generalized conclusions about the existence of OTV. Therefore, it is suggested that other studies investigate the same variables with participants that have possible risk for OTV.

The evidence provided by this study supports the pragmatic change hypotheses for the narrative production of older adults without psychosocial characteristics related to OTV. It was concluded that older participants showed more interest in personal reminiscence than younger participants. This result can be interpreted as a sign of greater mental model activation and a way of establishing identity through discourse. Rather than objective descriptions of actions, older adults presented significant descriptions of the past. Their discourse had more subjective remarks, but there was no significant difference between the number of irrelevant subjective remarks expressed by older and younger adults. It can be understood that instead of violating relevance rules, older adults have different discourse goals that require more subjective and indirectly relevant information than younger adults. These different communicative goals reflect the role that identity plays in oral narrative and raise light on the discussion of what can be considered relevant information in the perspective of the theory of context models (van Dijk, 2003).

We provide evidence that young and older adults' narratives differ in the expression of indirectly related ideas, preference for personal narratives, repeated ideas and subjective remarks. These might represent an increase in the expression of the mental scenery of stories, which suggests a possible age-related change in pragmatic aspects of narrative production. This view opposes from discourse decline perspectives on aging, which posit a decrease in coherence. However, it is important to consider educational and social features of samples when studying cognitive aging (Finley, Ardila, & Roselli, 1991). Our discourse tasks were conducted with small groups of younger and older adults that share certain educational and social particularities, such as higher level of education and considerable social activity, which are not common features for the majority of the Brazilian population. The results of this study must be replicated with larger samples, examining educational and social effects on pragmatic characteristics of narrative across a range of older and younger adult groups differing on education and social activity. Prior research has essentially focused on the relevance of utterances produced in discourse tasks. However, our framework suggests that pragmatic features such as subjectivity and preference for personal narratives can be informative domains in the study of older adults' discourse.

The literature suggests that older adults use compensation strategies when experiencing difficulties for recalling information (Finley & Rothberg, 1990). It is possible that a greater amount of indirectly relevant ideas are expressed by older adults as a strategy for compensating problems in the retrieval of progressive actions. That is, older adults would compensate for these difficulties by modifying the expression of information in a less focused and subjective manner, activating preserved components of their mental models. This hypothesis illustrates a current perspective in cognitive aging, a trend that considers the effects of brain plasticity in older age. This intriguing possibility of compensation may occur because personal narratives are subject to personal reinterpretation. We suggest this as an area for future research. A possible question for future studies is whether ease- and difficulty-of-retrieval will have effects on subjectivity and relevance of narrative production. The focus of this paper was on narrative situations in which the experience may come to mind in an easier manner. Instructions favored an easily recalled narrative by asking for the story telling of events that must have been important, interesting or unusual. However, when recalling a historical event, or an infrequent experience, the expectation may be that specific features of the episode would be harder for older participants to access. In such contexts, the difficulty-of-retrieval of information may be particularly informative in testing the amount of subjective and indirectly relevant content expressed.

References

Arbuckle, T., & Gold, D. (1993). Aging, inhibition, and verbosity. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 48(5), 225-232. [ Links ]

Arbuckle, T., Nohara-Le Clair, M., & Pushkar, D. (2000). Effect of off-target verbosity on communication efficiency in a referential communication task. Psychology and Aging, 15(1), 65-77. [ Links ]

Benton, A. L., & Hamsher, K. (1976). Multilingual Aphasia Examination. Iowa City, IA: AJA. [ Links ]

Boden, D., & Bielby, D. (1983). The past as resource: A conversational analysis of elderly talk. Human Development, 26, 308-319. [ Links ]

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. (2002). Perfil dos idosos responsáveis pelos domicílios no Brasil 2000: Vol. 9. Estudos e pesquisas: Informação demográfica e socioeconômica. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Autor. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (1997). Atos de significação (S. Costa, Trad.). Porto Alegre, RS: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (1999). Narratives of aging. Journal of Aging Studies, 13(1), 1-7. [ Links ]

Burke, D. (1997). Language, aging, and inhibitory deficits: Evaluation of a theory. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 52B(6), 254-264. [ Links ]

Chaves, M. L., & Izquierdo, I. (1992). Differential diagnosis beetween dementia and depression: A study of efficiency increment. Acta Neurologica Scandinavia, 85, 378-382. [ Links ]

Finley, G. E., Ardila, A., & Roselli, M. (1991). Cognitive aging in illiterate Colombian adults: A reversal of the classical aging pattern? Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 25(1), 103-105. [ Links ]

Finley, G. E., & Rothberg, S. (1990). Retrieval strategies of older and younger adults for recalling names and misplaced objects. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 24(1), 99-100. [ Links ]

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-Mental State. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189-198. [ Links ]

Gold, D., Andres, D., Arbuckle, T., & Schwartzman, A. (1988). Measurement and correlates of verbosity in elderly people. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 43(2), 27-33. [ Links ]

Gold, D., Andres, D., Arbuckle, T., & Zieren, C. (1993). Off-target verbosity and talkativeness in elderly people. Canadian Journal on Aging, 12(1), 67-77. [ Links ]

Gold, D., & Arbuckle, T. (1995). A longitudinal study of off-target verbosity. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 50B(6), 307-315. [ Links ]

James, L., Burke, D., Austin, A., & Hulme, E. (1998). Production and perception of "verbosity" in younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 13(3), 355-367. [ Links ]

Jose, P. E., & Brewer, W. F. (1984). Development of story linking: Character identification, suspense, and outcome resolution. Developmental Psychology, 20(5), 911-924. [ Links ]

Juncos-Rabadan, O., Pereiro, A., & Rodriguez, M. S. (2005). Narrative speech in aging: Quantity, information content, and cohesion. Brain and Language, 95(3), 423-434. [ Links ]

Korolija, N. (2000). Coherence-inducing strategies in conversations amongst the aged. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 425-462. [ Links ]

Krzemien, D. (2007). Estilos de personalidad y afrontamiento situacional frente al envejecimiento en la mujer. Revista Interamericana de Psicologia, 41(2), 139-150. [ Links ]

Mansur, L. L. (1991). As correções no discurso de idosos. Revista Distúrbios da Comunicação, 4(1), 94-94. [ Links ]

Murray, K. (1988). The construction of identity in the narratives of romance and comedy. In J. Shotter & K. Gergen (Eds.), Texts of identity (pp. 176-205). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Parente, M. A., Capuano, A., & Nespoulous, J. (1999). Ativação de modelos mentais no recontar de histórias por idosos. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 12(1), 157-172. [ Links ]

Randall, L. (1999). Narrative inteligence and the novelty of our lives. Journal of Aging Studies, 13(1), 8-18. [ Links ]

Reitan, R., & Davison, L. (1974). Clinical neuropsychology: Current state and applications. Washington, DC: Winston. [ Links ]

Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reaction. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18, 643-662. [ Links ]

Trenerry, M. R., Crosson, B., DeBoe, J., & Leber, W. R. (1989). The Stroop neuropsychological screening test. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assesment Resources. [ Links ]

van Dijk, T. (1996a). Estruturas y funciones del discurso (M. Gann & M. Mur, Trans.). Madrid, España: Siglo Veintiuno. (Original work published 1980) [ Links ]

van Dijk, T. (1996b). La ciencia del texto (S. Hunzinger, Trans.). Barcelona, España: Paidós Comunicación. (Original work published 1983) [ Links ]

van Dijk, T. (1998). Texto y contexto: semántica y pragmática del discurso (J. D. Moyano, Trans.). Madrid, España: Catedra. [ Links ]

van Dijk, T. (2001). Algunos principios de la teoría del contexto. ALED. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios del Discurso, 1(1), 69-82. [ Links ]

van Dijk, T. (2003). Contextual knowledge management in discourse production. Paper presented at the Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Society for Text and Discourse, Madrid, España. [ Links ]

Yesavage, J. A., Brink, T. L., Rose, T. L., & Lurn, O. (1983). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatry Resources, 17, 37-49. [ Links ]

Received 03/12/2007

Accepted 04/09/2008

Lenisa Brandão. Speech-Language Pathologist. Masters and Doctoral degree in Psychology at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), with a one year PhD internship (doutorado-sanduíche, funded by CAPES) in Neuropsychology at Hospital del Mar (Barcelona, Spain). Was, in 2005-2006, a Post-doc in Eye-tracking at Lund University (Sweden) funded by IFUW and, since 2007, is a Post-doc in Psycholinguistics at Universidade Nova de Lisboa (Portugal) funded by FCT.

Maria Alice de Mattos Pimenta Parente. Speech-Language Pathologist. Doctoral degree in Psychology at Universidade de São Paulo (USP). Adjunct Professor at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). Has been a Post-doc at the Universities of Montreal (1990-1992), Tolouse III (2001-2002) and Beijing (2006-2007) in the area of Neuropsychology.

1 Address: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Instituto de Psicologia, Rua Ramiro Barcelos, 2600, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil, CEP 90035-003. Tel.: (51) 3308 5246; Fax: (51) 3308 5473.

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI