Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho

versión On-line ISSN 1984-6657

Rev. Psicol., Organ. Trab. vol.16 no.4 Brasília dic. 2016

https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2016.4.12575

The saying and the doing in research on WOP

O dizer e o fazer nas pesquisas em POT

El decir y el hacer en las investigaciones en POT

Luciana MourãoI; Antônio Virgílio Bittencourt BastosII; Roberval Passos de OliveiraIII

IUniversidade Salgado de Oliveira, Niterói, RJ, Brasil

IIUniversidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Bahia, Brasil

IIIUniversidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia, Santo Antônio de Jesus, BA, Brasil

ABSTRACT

Research on Work and Organizational Psychology - WOP - tends to investigate its phenomena based on what is said, either through surveys or interviews. To what extent do we perceive the complexity of the area's constructs exclusively based on Saying? What explains such predominance? Such questions guided this theoretical essay, which is based on an analysis of the characteristics of the scientific production on some classic themes in organizational behavior. We conclude that the predominance of the comprehension of phenomena based on the subjects' accounts is due to both the ontological characteristics of its object and to operational considerations in the conduct of research. It would be appropriate, however, to explore the operational permeability of the object more closely and consider epistemological changes that strengthen the results obtained from analyses based on different perspectives. As an example, case studies are mentioned, as well as studies combining interviews and observations.

Keywords: epistemology; ontology; Work and Organizational Psychology.

RESUMO

As pesquisas em Psicologia Organizacional e do Trabalho -POT tendem a apreender seus fenômenos a partir do que é dito, seja por meio de surveys ou de entrevistas. Até que ponto, exclusivamente a partir da fala damos conta da complexidade dos construtos da área? O que explica tal predomínio? Tais questões guiaram o presente ensaio teórico que se apoia na análise das características da produção científica de alguns temas clássicos em Comportamento Organizacional. Conclui-se que o predomínio da apreensão dos fenômenos a partir de relatos dos sujeitos deve-se tanto a características ontológicas do seu objeto de estudo, quanto a razões operacionais na condução das pesquisas. Contudo, seria oportuno explorar mais atentamente a permeabilidade operativa do objeto e considerar variações epistemológicas que fortaleçam os resultados obtidos com análises em diferentes perspectivas. Como exemplo são mencionados os estudos de casos, e estudos que reúnam entrevistas e observações.

Palavras-chave: epistemologia; ontologia; Psicologia das Organizações e do Trabalho.

RESUMEN

Las investigaciones en Psicología Organizacional y del Trabajo -POT, tienden a captar sus fenómenos a partir de lo que es dicho, sea por medio de surveys o de entrevistas. ¿Hasta qué punto, exclusivamente a partir del habla, podemos manejar la complejidad de los constructos del área? ¿Cómo se explica tal predominio? Tales preguntas guiaron este ensayo teórico, basado en un análisis de las características de la producción científica de algunos temas clásicos en comportamiento organizacional. Se concluye que el predominio de la comprensión de los fenómenos en POT, a partir de los relatos de los sujetos, se debe tanto a las características ontológicas del objeto de estudio de la Psicología, como a las razones operacionales en la conducción de las investigaciones. Sin embargo, sería conveniente explorar más de cerca la permeabilidad del funcionamiento del objeto y considerar los cambios epistemológicos que fortalecen los resultados obtenidos de los análisis desde diferentes perspectivas. Se mencionan, como ejemplos, los estudios de casos y los estudios que reúnen entrevistas y observaciones.

Palabras-clave: epistemología; ontología; Psicología de las Organizaciones y del Trabajo.

The broad domain of phenomena that shape the lives of individuals and groups at work and in organizational contexts offers a wide and diversified range of objects for research. These phenomena relate to distinct levels of analysis, ranging from the intraindividual to the sociocultural context (Puente-Palacios, Porto, & Martins, 2016), and involve complex processes, the determination of whose causality represents a challenge. Cropping these phenomena, naming them, conceptualizing them and particularly defining how they will be accessed, described, measured or assessed represents a basic step in any scientific research process. We depart from the premise that the methodological decisions involved in a study are subordinated to the research problem and, consequently, to the concepts used to define the phenomena.

The psychological phenomena are traditionally accessible by: (a) hearing people talk about (describe, report on, speak, narrate) aspects of their personal, private life, inaccessible but through their Saying, or aspects of the external world as perceived or signified by the person; and (b) observing people in their most spontaneous or automatic reactions (facial expressions for example) and in their Doing in response to the context (behaviors, interactions etc.). Accessing the phenomena in Work and Organizational Psychology -WOP through Saying or Doing would therefore be part of theoretical and methodological decisions in the design and development of a study.

The main question discussed in this theoretical essay can be formulated as follows: To what extent do studies that access the phenomena exclusively based on Saying cope with the complexity of the constructs by which we are challenged to understand and change? This question arouses ontological (nature of our object), epistemological (foundations of our scientific practice) and methodological (how to access our study objects) reflections.

The thesis we defend in this theoretical essay is that the nature of some phenomena in Psychology requires an approach that integrates Saying and Doing. Therefore, we depart from two premises, which are: (a) in scientific research, the methodological procedures represents ways of approaching and focusing on the problem or phenomenon defined as the study object (Cohen & Nagel, 1934); and (b) Saying and practice are aspects that do not necessarily overlap nor oppose one another; they are complementary to understand the reality (Magnani, 1986).

Thus, we do not propose a dichotomy in research on WOP in terms of Saying versus Doing. We assume the additional premise that the word is also a form of Doing (Austin, 1990/1962). Nevertheless, evidence exists that, for many phenomena in WOP, the fact that we restrict ourselves to investigating the Saying prevents us from incorporating fundamental elements for the appropriate apprehension of the phenomena, to the extent of ignoring their possible meanings in the daily work relations.

This characteristic is documented in the literature: scientific research in WOP almost always centers on the apprehension of what people say, whether through quantitative or qualitative approaches (Aguinis, Pierce, Bosco, & Muslin, 2009). Despite important methodological reflections in research in the area (Aguinis & Vandenberg, 2014; Hoon, 2013; King, Hebl, Morgan, & Ahmad, 2012), the hegemony of the report almost implies that we abandon Doing, and especially the relation between Saying and Doing when individual and/or collective phenomena are studied in the world of work. Hence, research in WOP seems to be exclusively focused on apprehending the phenomenon through communication, with limited emphasis on observation (Aguinis et al., 2009).

Some examples illustrate what we affirm. In studies on performance at work, this phenomenon is generally considered based on what the subject informs (self-assessment) or what another subject (colleague, superior or clients) says (hetero-assessment). In studies on organizational commitment, although managers mainly depart from behaviors to assess their collaborators, research largely centers on scales in which the worker "declares" his commitment. The same could be affirmed for behavioral studies of organizational citizenship. Despite the name "behavior", these are limited to what people say that they do.

Hence, although the phenomena in WOP cover not only what the person says he does, but also what he actually does, our research generally focuses only on what she says. At the first level, the person embraces beliefs that guide his Doing. At the second, he operates in the world and transforms himself and his surroundings. Reflecting on the articulation between the Saying and the operational Doing is a critical aspect for some central constructs of WOP.

Thus, the question should be raised what factors justify the hegemonic trend in our research area - in quantitative or qualitative approaches - of remaining limited to Saying as a strategy to access the phenomena of WOP? What explains the limited emphasis on the search for methodological strategies that integrate Saying and Doing? What implications does this entail for the nature of the knowledge produced? Is the Saying consistent with the Doing or not?

To present our reflections on the complex issues raises, the text was organized in three parts. The first discusses Saying and Doing in the field of the human and social sciences and the philosophical and epistemological perspectives on these forms of looking at the phenomena. The second part focuses on Saying and Doing in WOP research, showing how the main phenomena in the area have been studied, considering an ontological perspective on research in Psychology. In that part, we depart from an empirical survey of the characteristics of research in Organizational Behavior published in Brazil in recent years. The third and final part presents the epistemological challenges the area is confronted with and their relation with the way we access the phenomena in research in WOP.

Saying and Doing in the human and social sciences

Saying and Doing are a source of reflection in the human and social sciences in general and in Philosophy in particular. From different perspectives, philosophers of language like Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951), John Langshaw Austin (1911-1960) and John Rogers Searle (1932- ) present relevant contributions on the theme. It should be highlighted that, despite converging in many aspects, Wittgenstein and Austin developed their thinking independently and that Searle continued the studies by Austin. In view of the objective of this essay, we present some central ideas of these authors, as they deconstruct the idea of antagonism between Saying and Doing, considering that Saying is by itself an Doing.

Wittgenstein (1975/1953) introduces an important distinction between saying and showing. According to him, the logical propositions do not transmit descriptive contents and therefore cannot say anything about the world, despite showing something about it. The author argues that there are limits to language and that some themes, such as the mystical, ethics and esthetics can only be shown, but not said because they lie beyond the reach of our language. Wittgenstein considered that, even for what can be treated through language, the meanings are not homogeneous, as the meaning of the words is linked to what the speaker or listener does with that expression. Another important reflection Wittgenstein presents is that describing or representing the facts is not necessarily the primary function of language, as it incurs in the mistake of turning a particular language game into a paradigm for all others.

Austin (1990/1962), in turn, created the theory of speech acts, whose initial proposal distinguishes between constative (describe or report on a state of things) and performative utterances (when uttered, they perform an Doing and do not submit to the criterion of verifiability). The author focused on the performative utterances, which combine speech and Doing, and on the conditions for these utterances to happen (conditions of happiness). These utterances are generally expressed in the first person singular of the indicative, in the affirmative form and in the active voice, but Austin shows several possibilities of a performance utterance without complying with these grammatical conditions. The author later concluded that all utterances are performative.

Searle (1969) continues with Austin's theory of speech acts, considering that uttering a phrase involves a purposeful act, related to the content communicated, as well as an illocutionary act, related to the act performed in language. The separation between these acts permits the separation of the speech acts into direct/primary or indirect/secondary. The author creates five distinct categories of speech acts, which he calls: (a) representative, which evidences the speaker's belief on whether a proposal is true; (b) directive, which are intended to make someone do something; (c) commissive, which make a future Doing by the speaker explicit; (d) expressive, which express feelings; and (e) declarative, which produce a new and external situation.

The reflections philosophers of language present converge to the understanding that the word is by itself an act. And, in fact, in the different contexts of life, including work and organizations, when we speak, when we express what we think, when we use our voice, we are acting and transforming the reality. In a study, however, when we only listen to what people think or feel about a phenomenon, we are capturing that phenomenon in the complexity of its structure in the context of work?

Burrell and Morgan (1979), in a seminal work on sociological paradigms of organizational research, characterize four fundamental and mutually exclusive paradigms that are based on different sets of metatheoretical premises on the nature of the social sciences and of society itself. These paradigms are presented in an organized matrix based on two axes, which are: (a) a concept of society, which opposes a sociology of radical change to a sociology of regulation; and (b) the concept of social science, which opposes a subjective to an objective approach. The combination of these axes gives rise to four paradigms, which are: the functionalist (Regulation/Objective), the radical humanistic (Change/Subjective), the radical structuralist (Change/Subjective), and the interpretive (Regulation/Subjective). Each of these paradigms comes with its own arguments and consequently produces distinct and opposite analyses of social life.

This paradigmatic diversity is present not only in organizational studies, but in all social sciences, and is manifested in different strategies to measure its phenomena based on Saying and Doing. On the one hand, there exists a concept that science is a complex human process that involves a commitment to experience the world as it is, independently of preconceived notions or hypotheses on its nature (Ray, 2011). On the other hand, there is the concept that distinguishes two types of data: data from the world itself and from the represented world, constituted through communication processes (Bauer, Gaskell, & Allum, 2000; Berger & Luckmann, 1979).

Any method is associated with situations, research problems and contexts that contribute to indicate or counterindicate its use. The observations, for example, allow the researcher to describe existing situations, using the five senses to provide a written photograph of the situation under analysis (Erlandson, Harris, Skipper, & Allen, 1993). Therefore, this type of method also involves representation. On the one hand, observations with scientific rigor can permit a holistic understanding of the phenomena being studied. On the other, the limitations of the method recommend its use in combination with other data collection strategies, such as interviews, documentary analyses and surveys (DeWalt & DeWalt, 2011). In addition, the analysis of observation data without feedback to the subjects (using some communication method) for the sake of further understanding of what was observed, can produce results that are hardly meaningful or interpreted inappropriately.

Hence, observations offer the benefit of providing the researchers with ways to capture the non-verbal expression of feelings (Schmuck, 1997), without the same type of imprecisions as the verbal reports (Kawulich, 2005); at the same time, the observation is subject to a set of possible biases that can result from its use, particularly related to stereotypes and social prejudices, so frequently addressed in social cognition studies. In addition, the observation can reflect events from a specific moment (which can be considered frequent) and does not permit the verification of attitudes either, as it is focused on behavior. In that sense, the observation of behaviors without the individuals' report can lead to a research in which the motivations and meanings of Doing are ignored. In addition, as human beings make the observations, the researcher's personal characteristics (gender, ethnic origin, social class, theoretical approach etc.) can affect his perception, analysis and interpretation of the facts (Kawulich, 2005).

At the other end of the observation, data are collected by communication. The word is a form of representation that precedes drawing and writing (Queiroz, 1992). The representation consists of individual experiences and this concept puts emphasis on what is said (Magnani, 1986). On the one hand, the collection methods by means of communication permit a representation of the world and a construction of meaning. On the other, however, the report is also subject to self-censorship, self-promotion (Queiroz, 1992), social desirability (Suryani, Tair, & Villieux, 2015) and other sources of bias that limit the apprehension of the research phenomenon. Doing research in the social sciences obviously implies accepting the limitations of the represented world and considering that an experience cannot be fully transferred to anyone else: what is transmitted is not the experience as it is experienced, but its meaning (Ricoeur, 1976). The experience lived remains private, but its sense and meaning can become public through the mediation of language.

In the same sense, Geertz (1989) considers that the data are by themselves a construction by the researcher of the constructions by other people, therefore referring to something constructed/something modeled. The author does not consider that that makes the data false, but analyzes that they are as if it were a version, among many, of the reality observed, a version that should be cross-checked with other versions elaborated inside the scientific language.

Thus, both one type of method and the other are affected by subjective aspects, as there are no observations or reports that can be considered neutral. Therefore, the polarity between Saying and Doing is not directly associated with the subjectivist/objectivist polarity in science, when adopting that the apprehension of any phenomenon involves some level of construction by the researcher. This construction is revealed when delimiting and conceptualizing its study object and, consequently, when choosing the forms of accessing, describing, analyzing and explaining it. This methodological decision is the core of what will be discussed next.

Saying and Doing in Research in WOP

In research in WOP, an almost exclusive use of reports is observed, whether in the foreign or in the Brazilian literature. In the content analysis by Aguinis et al. (2009), based on the 193 articles published in the first ten volumes of the journal Organizational Research Methods (ORM), covering the period from 1998 till 2007, it was evidenced that surveys are predominant, mainly in the electronic version. Whether in quantitative or qualitative studies, the authors found a predominance of data collection based on reports, with few studies deriving from observations in the work environment.

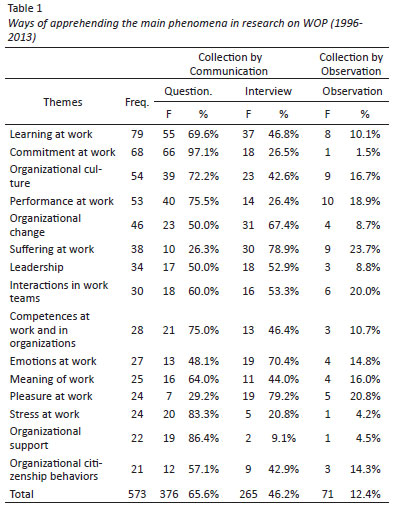

An analysis of 694 Brazilian studies on Organizational Behavior, published in 15 journals in Psychology and Administration between 1996 and 2013, appoints 47% of quantitative studies, 39% qualitative and 14% mixed-method studies, while only 12.4% included observation as a way to access the phenomena. This preponderance of Saying as a way to access the phenomena in research in WOP arouses reflections on the causes of this preference. This hegemony is probably due to different reasons, ranging from ontological aspects of Psychology to pragmatic issues of research in work organizations.

From the ontological viewpoint, it should be taken into account that an important part of Psychology is basically focused on dispositional phenomena (related to the singular universe of each person, involving thoughts, perceptions, ideas, beliefs, values, attitudes, emotions and feelings) or uses dispositional constructs to understand behaviors or Doing in a context. The etymology itself of the word refers to this, as Psychology derives from psique (soul) and logos (reason or knowledge), being characterized as the science of the internal meaning (Canguilhem, 1973). We obviously are not ignoring that Psychology is plural and has been understood as biological science, of the mind, of animal and human behavior. Nevertheless, the highlight on dispositional phenomena may contribute to explain the reason for emphasizing the Saying, considered as verbal behavior and as a way to understand the meanings people construct.

From the perspective of research praxis, there are also reasons that justify the primacy of data collection based on Saying. Three types of difficulties can be associated with the use of observation, some of which are specifically focused on the environment of the work organizations. The first difficulty is the access to the organizations. In some themes, in which observation would be possible and recommendable, this option is difficult for the researcher, due to the fact that many organizations do not authorize the entry of researchers for direct observation. In addition, the presence of an observer can affect the performance in the natural situation, which can be even more complex in a work situation with targets and expected products.

Another difficulty refers to the limitation of the observation methods in large-scale surveys. The time spent on observation tends to be much longer than that spent to apply questionnaires or hold interviews. In research through observation, the time shapes the sample size, which is generally insufficient (Berlin, Glasser, & Ellenberg, 2008). It is hard for researchers to be available as many hours as a large-scale observation sample requires, also because not only the observation period, but also the analysis of the observations demands time. The challenge in terms of the number of hours invested in observation is even greater in those cases in which the research design involves several organizations. Short observation periods are particularly concerning for phenomena that take time to manifest themselves or whose effects take place in the medium and long term. In those cases, these effects may be underestimated or even unnoticed.

Finally, a third difficulty refers to the reproducibility of the observational studies, due to the subjectivity of the process, and mainly to the specific conditions and environment (Berlin et al., 2008). The indication that observations be made by more than one observer for the sake of greater reliability of the observation process (Batista, 1977; Landis & Koch, 1977) further expands the investment required from researchers in this type of collection. In that sense, the choice of this method is more complex and difficult to implement.

Therefore, we conclude that the concept of Psychology as an area eminently focused on listening, associated with operational difficulties to develop research by observation, leads to this scenario of hegemony of reports to the detriment of operational Doing, and to an also small number of studies that combine Saying and Doing. Therefore, a discussion is needed on the themes studied in WOP: to what extent is research exclusively based on reports sufficient to understand the phenomena in the area?

To identify if the way to access the phenomena - whether through communication or observation - is somehow related to the research theme, an excerpt was made of the 15 most investigated themes (573 publications) in organizational behavior. The results show that the choice of the data collection method varies according to the research theme. The constructs suffering at work, pleasure at work and interactions in teams show the highest percentages of data collection through observation (23.7%, 20.8% and 20%, respectively). At the other end, research on commitment, occupational stress and organizational support show lower percentages of data collected through observation (1.3%, 4.2% and 4.5%, respectively), as shown in Table 1.

If the nature of each of these themes is analyzed and the possible coherence with the way the phenomenon is accessed - focused on Saying or Doing -no explanations are identified based on the ontology of the research object. Essentially intrinsic themes (such as pleasure and suffering at work) are more investigated through Doing than themes whose characteristic is based on behaviors (such as organizational citizenship or performance). As this mapping only took into account organizational behavior studies, themes like the activity clinic and ergonomics, more traditional in research involving Saying and Doing, were not addressed.

In research in ergonomics, the ways of accessing the phenomenon tend to be broader, with a view to methodologically moving from the appearance of the phenomenon to its essence (Ferreira, Almeida, & Guimarães, 2013). To respond to this premise, the ergonomic analysis of the activity considers different alternative tools, such as: documentary analysis, interviews, free and systematic observations, physical-environmental measuring (ergonomic inspection), body maps or diagrams, psychometric scales and content analyses (Ferreira et al., 2013). In that sense, the area of activity ergonomics can be considered an exception in research in WOP, as it accesses the phenomena through Saying and Doing, establishing observation as the main technique to apprehend the work reality (Ferreira, 2015).

Despite some exceptions like the field of ergonomics, however, the focus on Saying is predominant in most research in WOP, whether in the Brazilian or international literature. In a literature review on wellbeing at work, Sonnentag (2015) alerts to the fact that most studies had been constructed based on self-report measures. The author considers that the use of this method can inflate the empirical relations between the predicted measures and outcomes. Sonnentag argues that future studies would benefit from the use of other types of measures, including objective data and data from observation (both focused on Doing), as well as reports from other sources (using hetero-assessment, but in this case maintaining the Saying as a way to access the phenomenon). According to the author, the exclusive use of self-report measures darkens the mechanisms underlying the dynamics of wellbeing and needs to be reconsidered, especially with regard to performance measures.

In themes like performance and organizational citizenship behaviors, when the phenomenon is also accessed through reports, the studies end up being investigations of intended or perceived behaviors. Due to the nature of these themes, essentially focused on Doing, the question is raised to what extent actual behaviors can be captured. Perhaps it would even be advisable for the names of these scales to include the words perception/intention - depending on the case - to alert to the fact that the results refer to perceptions and/or intentions, which can strongly differ from the behaviors.

At the other end, there are themes whose nature indicates studies based on self-reporting. Job Embeddedness is one example, as the assessment of the intention to remain in the company is a construct for which observation does not seem to be the best way to apprehend the phenomenon. In that case, the assessment comprises the intended behavior instead of the actual behavior, being related to the link the person establishes with the organization and with that person's reading of his/her career possibilities inside and beyond the current work organization (Lee, Burch, & Mitchell, 2014). Studies about the commitment to the job and the organization also entail a demand for information that can hardly do without the Saying, considering that they involve affects and attitudes and that the behaviors resulting from the commitment already characterize their consequent behaviors of organizational citizenship or performance at work.

In several themes, the characteristics of activities in WOP demand that the studies consider Saying and Doing in combination as a way to access the phenomena. Studies about learning are one example. Learning is a psychological process that refers to changes in the individual's behavior, which do not only result from maturing, but also from interaction with the context (Abbad & Borges-Andrade, 2014). Therefore, learning foresees a change that should be reflected in the Doing. But observing the Doing without including people's report can also lead to mistaken interpretations of the learning, as the nature of this construct is cognitive. Paradoxically, only 10.1% of Brazilian studies include observation as a way to access the phenomenon. The same seems to be the case in foreign research, as a recent literature review on the theme does not report on observation-based studies (Noe, Clarke, & Klein, 2014).

In a study by Katz, McCarty-Gillespie and Magrane (2003), in the field of learning, the skills of resident physicians to teach students in an outpatient context were investigated. The study used a systematic direct observation script and the results showed that, although feedback was frequently mentioned as a concern, feedback was provided in only 41% of the meetings. This result evidences that what is said is not always coherent with what is done.

A set of implications therefore derives from this limited emphasis on Doing in the sense of the performance of actions. Research based on reports (interviews, questionnaires, focus groups, scales) also focus on "Doing" of course, when we consider the word as a form of Doing (Austin, 1990/1962; Searle, 1969, 1979; Wittgenstein, 1975/1953). In WOP, however, we focus more on Saying and less on Doing in operational terms. In that sense, we believe that the hegemony of the report in research in the area affects our knowledge about the phenomena and its historical construction process. Therefore, researchers in WOP are challenged to reconsider their data collection options in the light of the nature of their research objects, as discussed next.

Forms of accessing the phenomena in WOP and the challenges the area is confronted with

Studies in WOP have produced a wide range of concepts and theories, without guaranteeing uniformity in their use. This has resulted in the construction of microtheories (Borges-Andrade & Zanelli, 2014). This lack of unicity leads to multiple theoretical perspectives and adaptations by the researchers, distancing the concepts form their theoretical origin (Oswick, Fleming, & Hanlon, 2011), based on the use of a series of epistemological paradigms that culminate in a lack of ontological compliance in organizational studies (Coelho-Junior, Meneses, Almeida, & Bernardo, 2015).

Conceptual fragmentation, overlapping and confusion entail the need for further investments in discussing the concepts and ways of accessing the phenomena (see Corradi, Marcon, Loiola, Kanan, & Vieira, 2016 and Rodrigues & Carvalho-Freitas, 2016) . The apparent lack of theoretical reflection in the process of choosing the data collection procedures in the area -with the absolute primacy of research by means of communication) - can represent an obstacle for the improvement of our research. One set of issues we have not discussed here, such as the apprehension of phenomena as processes or as something static for example (see Gondim, Bendassolli, Coelho Jr., & Pereira, 2016), would result in a picture similar to what was drawn in this essay. These reflections are important as they can help us to better understand the phenomena we work with.

It is a fact that the concepts used in WOP often derive from daily language and entail meanings the researcher is not always alert to. "The practice of operationally defining the terms of daily language is still disseminated in Psychology, although it has failed to prevent conceptual mix-ups in the psychological discourse" (Harzem, 1986, p. 48, authors' translation). In a field that basically rests on verbal reports (Aguinis et al., 2009), this can strongly affect the results and validity of the scientific studies.

As mentioned earlier, the dilemma studies in WOP experience reflect more general problems in the use of attitudinal or other constructs that refer to internal events to explain individuals' behaviors. In that sense, it would be important not to include behavioral intentions into the concept of attitude, adopting the definition by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) for example, who conceive attitude as an affective orientation towards an object and put forward intentions as intermediary links between the attitude and the observable behavior.

Although, on the one hand, a considerable set of threats exist on the validity of observational studies; on the other, recent studies show how to enhance the design, execution and analysis of the observations, like in large-scale intervention studies for example (Madigan et al., 2014). The recommendations for this type of research can be useful for WOP when the measuring of Doing contributes to understand the phenomena.

The systematic observation of certain phenomena from the job world can also be useful to predict repetition over time. Many studies that focus on future intended behavior based on self-reporting could perhaps be replaced and/or complemented by studies focused on Doing. The Poisson distribution could be adopted in relation to systematically observed phenomena (probability of a discrete random variable that expresses the probability that a series of events will happen in a certain time period if these events happen independently of when the latest event took place - Mantell, 1966). This distribution could represent a suitable probabilistic model to study many observable phenomena in the organizational world, such as the probability of occupational accidents or absenteeism within a certain time unit. In addition, it should be taken into account that technological advances have allowed for improvements in the observation process, deepening the data collection through video recording (Belei, Gimeniz-Paschoal, Nascimento, & Matsumoto, 2008).

Therefore, one of the challenges the field of research in WOP is confronted with is to avoid automatism in choosing the way the phenomena will be accessed. Each researcher needs to incorporate reflections on the ontological and epistemological dimensions involved in this choice into his practices. Greater refinement of the variables will incite their epistemological strengthening, including the conceptual problematization (Coelho-Junior et al., 2015).

In WOP as well as in the social sciences in general, in the Brazilian and foreign literature, there is an unmistakable predominance of research that adopts Saying - mainly based on self-reports - as the way to access individual and even collective phenomena. Although, in some themes, the nature of the research problem should guide the studies that also include Doing, in practice, that is not verified, whether due to the researchers' limited attention to ontological and epistemological aspects or to the difficulties with methods and tools to access the phenomena in distinct and complementary manners.

The homogeneity of the forms of accessing the phenomena in WOP makes it difficult to identify the extent to which the results would differ if the studies more frequently addressed Doing as well. The researchers' greater attention to Doing in the context of work would probably lead to very different results in several research domains. The same can be expected from a more intensive use of approaches that simultaneously consider the Saying and Doing, elaborating more complex analyses and reflections that are more in line with the nature of the research phenomenon.

Studies in WOP do not demonstrate attention to the distinction Wittgenstein (1975/1953) made between saying and showing. The discussions presented in this theoretical essay give the impressions that the limits for language Wittgenstein appointed are disregarded in research in this area, which seems to consider that all phenomena lie within the reach of our language. Reflection is needed on the extent to which we, in certain cases, transgress the rules imposed on the significant proposals, producing contradictions in our findings and theories. We should also consider the extent to which we are able, in our content analyses, to consider the heterogeneous meanings of the words and the different paradigms of the stakeholders in the research process.

In view of the paradigmatic diversity described by Burrel and Morgan (1979), two possible routes can be highlighted: (a) functional research should intensify the designs that involve one or few cases, reducing the presence of cross-sectional studies with large samples: this change would lead to the apprehension of the case based on multiple strategies, including observations of organizational actors' Doing; and (b) interpretive research could go beyond the content, discursive or narrative analyses - in which Saying is considered in its 'constative' and not in its performative characteristic, in line with Austin (1990/1962); or Saying mainly as an expressive act, in accordance with Searle (1969). The enhancement of ethnographic perspectives involving interviews and observation might be a fruitful course.

When we appoint such courses, we do not assume that one type of method or form of accessing the constructs is better than the other. We mainly signal the need for researchers in WOP to gain awareness of the ontological issues involved in the definition of the concepts and implications for the way of accessing the phenomena under analysis. The debate on these issues can contribute to the maturing of the field, especially if themes are identified in WOP that more urgently demand the combination of Saying and Doing, possibly involving a triangulation of methods (Flick, 2009).

In this article, some reflections were presented on the debates in WOP, but many others still need to be considered when the choice of ways to access the phenomena in this research area is at stake. It should be taken into account that problems surround the dominant tradition of assuming Saying (subjective variables) as the antecedent of Doing (behavioral variables). What theory of "mind" underlies the dominant form in which these dimensions are analyzed in WOP? What are the implications of the decisions on the ways to access the phenomena and the sense of the relations sought and established among the constructs under analysis? Are Saying and Doing coherent in research in the area? Why do we not use more case studies in WOP with a view to better describing the phenomenon, better delimiting it and, in that sense, gaining better conditions to assess the most suitable form of access to phenomena in the area?

To the extent that further research is developed in which Doing is considered as the analysis unit, other reflections can be developed on the link between the concepts of WOP and the way to apprehend the phenomena. And despite the limitations and challenges the choice of Doing as the analysis unit involves, research in WOP is expected to find alternatives to the current forms of knowledge production, moving towards greater theoretical, ontological and epistemological consistency in the field.

Finally, it should be taken into account that "decision and Doing are ended, but not finite acts, that is, their accomplishment, although reversible, leaves a history" (Munck, Munck, & Borim-de-Souza, 2011, p. 150, authors' translation). In that sense, studies in WOP can investigate not only the combination of Saying and Doing itself, but also the consequences of the Doing in terms of other Doing and attitudes that originate in social Doing.

References

Abbad, G. S., & Borges-Andrade, J. E. (2014). Aprendizagem humana em organizações de trabalho. In J. C. Zanelli, J. E. Borges-Andrade & A. V. B. Bastos (Orgs.), Psicologia, organizações e trabalho no Brasil (pp. 237-275). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Aguinis, H., Pierce, C. A., Bosco, F. A., & Muslin, I. S. (2009). First decade of organizational research methods: Trends in design, measurement, and data-analysis topics. Organizational Research Methods, 12(1),69-112. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2008.33643777 [ Links ]

Aguinis, H., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2014). An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure: Improving research quality before data collection. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1),569-595. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091231 [ Links ]

Austin, J. L. (1990/1962). Quando dizer é fazer. Palavras e ação (D. M. Souza Filho, Trad.). Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Batista, C. G. (1977). Concordância e fidedignidade na observação. Psicologia, 3(2),39-49. [ Links ]

Bauer, M. W., Gaskell, G., & Allum, N. C. (2000). Quality, quantity and knowledge interests: Avoiding confusions. In M. W. Bauer & G. Gaskell (Eds.), . Qualitative researching with text, image and sound: A practical handbook (pp. 3-18). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Belei, R. A., Gimeniz-Paschoal, S. R., Nascimento, E. N., Matsumoto, P. H. V. R. (2008). O uso de entrevista, observação e videogravação em pesquisa qualitativa. Cadernos de Educação, 30(1),187-199. [ Links ]

Berger P., & Luckmann, T. (1979). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Berlin J. A., Glasser S. C., & Ellenberg S. S. (2008). Adverse event detection in drug development: Recommendations and obligations beyond phase 3. American Journal Public Health, 98(8),1366-1371. [ Links ]

Borges-Andrade, J. E., & Zanelli, J. C. (2014). Psicologia e produção do conhecimento em organizações e trabalho. In J. C. Zanelli, J. E. Borges-Andrade & A. V. B. Bastos (Ogs.), Psicologia, organizações e trabalho no Brasil (pp. 583-608). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Burrel, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis: Elements of the sociology of corporate life. London: Heinemann Educational Books. [ Links ]

Canguilhem, G. (1973). O que é a psicologia. Tempo brasileiro, 30(31),104-123. [ Links ]

Coelho-Junior, F. A., Meneses, P. P. M., Almeida, R. F., & Bernardo, A. J. (2015). How conceptual analysis can contribute to the theoretical refinement in organizational theories? Business and Management Review, 4(5),247-255. [ Links ]

Cohen, M., & Nagel, E. (1934). An introduction to logic and scientific method. New York: Harcourt. [ Links ]

Corradi, A. A., Marcon, S. R. A., Loiola, E., Kanan, L. A., & Vieira, L. R. (2016). Empirical studies in WOP in Brazil: A paradigmatic analysis. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 16(4),349-357. doi: 10.17652/rpot/2016.4.12638 [ Links ]

DeWalt, K., & DeWalt, B. R. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers (2nd ed.). Plymouth: AltaMira Press. [ Links ]

Erlandson, D. A., Harris, E. L., Skipper, B. L. & Allen, S. D. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: A guide to methods. Newbury Park: Sage. [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2009). Qualidade na pesquisa qualitativa. Porto Alegre: Bookman, Artmed. [ Links ]

Ferreira, L. L. (2015). Sobre a análise ergonômica do trabalho ou AET. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Ocupacional, 40(131),8-11. doi: 10.1590/0303-7657ED0213115 [ Links ]

Ferreira, M. C., Almeida, C. P., & Guimarães, M. C. (2013). Ergonomia da atividade: Uma alternativa teórico-metodológica no campo da psicologia aplicada aos contextos de trabalho. In L. O. Borges & L. Mourão (Orgs.), O trabalho e as organizações: Atuações a partir da psicologia (pp. 557-580). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Geertz, C. (1989). A interpretação das culturas. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar Editores. [ Links ]

Gondim, S., Bendassolli, P. F., Coelho Jr., F., & Pereira, M. E. (2016). Explanatory models to work and organizational phenomena: Epistemological, theoretical and methodological issues. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 16(4),316-323. doi: 10.17652/rpot/2016.4.12641 [ Links ]

Harzem, P. (1986). The language trap and the study of pattern in human Doing. In T. Thompsoon & M. D. Zeiler (Eds.), Analysis and integration of behavioral units (pp. 45-53). Hillsdade: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Hoon, C. (2013). Meta-synthesis of qualitative case studies: An approach to theory building. Organizational Research Methods, 16(4),522-556. doi: 10.1177/1094428113484969 [ Links ]

Katz, N. T., McCarty-Gillespie, L., & Magrane, D. M. (2003). Direct observation as a tool for needs assessment of resident teaching skills in the ambulatory setting. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 189(3),684-687. doi: 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00883-4 [ Links ]

Kawulich, B. B. (2005). Participant observation as a data collection method [81 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschun/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(2),1-28. [ Links ]

King, E. B., Hebl, M. R., Morgan, B. W., & Ahmad, A. S. (2012). Field experiments on sensitive organizational topics. Organizational Research Methods, 16(4),501-521. doi: 10.1177/1094428112462608 [ Links ]

Landis J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1),159-74. [ Links ]

Lee, T. W., Burch, T. C. & Mitchell, T. R. (2014). The story of why we stay: A review of job embeddedness. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1,199-216. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091244 [ Links ]

Madigan, D., Stang, P. E., Berlin, J. A., Schuemie, M., Overhage, M., Suchard, M. A.,...Ryan, P. B. (2014). A systematic statistical approach to evaluating evidence from observational studies. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application, 1,11-39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-statistics-022513-115645 [ Links ]

Magnani, J. G. C. (1986). Discurso e representação, ou de como os Baloma de Kiriwina podem reencarnar-se nas atuais pesquisas. In R. Cardoso (Org.), A aventura antropológica: Teoria e pesquisa (pp. 127-140). Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Mantell, L. H. (1966). On laws of special abilities and the production of scientific literature. American Documentation, 17(1),8-16. [ Links ]

Munck, L., Munck, M. G. M., & Borim-de-Souza, R. (2011). Sustentabilidade organizacional: A proposição de uma framework representativa do Fazer competente para seu acontecimento. Gerais - Revista Interinstitucional de Psicologia, 4(n.spe),147-158. [ Links ]

Noe, R. A., Clarke, A. D. M., & Klein, H. J. (2014). Learning in the twenty-first-century workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1),245-275. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091321 [ Links ]

Oswick, C., Fleming, P., & Hanlon, G. (2011). From borrowing to blending: Rethinking the processes of organizational theory building. Academy of Management Review, 36(2),318-337. [ Links ]

Puente-Palacios, K., Porto, J. B., & Martins, M. C. F. (2016). A emersão na articulação de níveis em Psicologia Organizacional e do Trabalho. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 16(4),358-366. doi: 10.17652/rpot/2016.4.12603 [ Links ]

Queiroz, M. I. P. (1992). O pesquisador, o problema da pesquisa, a escolha de técnicas: Algumas reflexões. In A. B. S. G. Lang (Org.), Reflexões sobre a pesquisa sociológica (pp. 13-29). São Paulo: Centro de Estudos Rurais e Urbanos. [ Links ]

Ray, W. J. (2011). Methods: Toward a science of behavior and experience (10th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P. (1976). Teoria da interpretação: O discurso e o excesso de significado. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, A. C. A., & Carvalho-Freitas, M. N. (2016). Theoretical fragmentation: Origins and repercussions in Work and Organizational Psychology. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 16(4),310-315. doi: 10.17652/rpot/2016.4.12630 [ Links ]

Schmuck, R. (1997). Practical doing research for change. Arlington Heights: IRI/Skylight Training and Publishing. [ Links ]

Searle, J. R. (1979). Expressions and meaning: Studies in the theory of speech acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sonnentag, S. (2015). Dynamics of well-being. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1),1-33. doi 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111347 [ Links ]

Suryani, A. O., Tair, E., & Villieux, A. (2015) Socially desirable responding: Enhancement and denial in 20 countries. Cross-Cultural Research, 49(3),227-249. doi: 10.1177/1069397114552781. [ Links ]

Wittgenstein, L. (1975/1953). Investigações filosóficas (J. C. Bruni, Trad.). In V. Civita (Ed.), Os pensadores (pp. 11-226). São Paulo: Abril Cultural. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Luciana Mourão

Universidade Salgado de Oliveira, Campus Niterói

Rua Marechal Deodoro, 217, Centro

Niterói, RJ, Brasil, 24030-060

Email: mourao.luciana@gmail.com

Recebido em: 04/07/2016

Primeira decisão editorial em: 08/08/2016

Versão final em: 12/09/2016

Aceito em: 12/09/2016