Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Compartir

Temas em Psicologia

versión impresa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.27 no.4 Ribeirão Preto oct./dic. 2019

https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2019.4-04

ARTICLE

Empirical evidence on the relationship between coparenting and temperament: a systematic review of the literature

Evidências empíricas sobre a relação entre coparentalidade e temperamento: uma revisão sistemática da literatura

Evidencias empíricas sobre la relación entre coparentalidad y temperamento: una revisión sistemática de la literatura

Monica Barreto ; João Paulo Koltermann

; João Paulo Koltermann ; Maria Aparecida Crepaldi

; Maria Aparecida Crepaldi ; Mauro Luís Vieira

; Mauro Luís Vieira

Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, SC, Brasil

ABSTRACT

The aim of this review was to analyze the empirical studies that have measured temperament and coparenting. Accordingly, we sought to answer the question: "What is the relationship between the variables of coparenting and temperament in empirical studies, considering the different theoretical approaches, the different instruments used and families with children between zero and 11 years of age?" The databases chosen for this review were VHL-Psi, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. The VHL-Psi database was searched, however, no articles were found. A total of 28 articles were selected, which were analyzed in their entirety and described regarding the number of participants, method, instruments used and other variables measured. The results regarding the relationship between coparenting and temperament were organized into six categories. Only two articles indicated a lack of significant relationships between the two variables. Temperament as a predictor of coparenting and the moderating role of coparenting as a risk and protection factor were highlighted. Bidirectional relationships between variables were addressed in only three articles and the lack of studies in this direction was evident. Differences in the coparenting of fathers and mothers highlight the importance of gender discussions.

Keywords: Coparenting, temperament, systematic review.

RESUMO

O objetivo desta revisão foi analisar os estudos empíricos que mediram temperamento e coparentalidade. Para tanto, buscou-se responder à pergunta: "qual a relação entre as variáveis coparentalidade e temperamento em estudos empíricos, considerando as diferentes abordagens teóricas, os diferentes instrumentos utilizados em famílias com crianças entre zero e 11 anos?". As bases de dados escolhidas para a revisão foram BVS-PSI, Psycinfo, Pubmed, Scopus e Web of Science. Na base de dados nacional BVS-PSI nenhum artigo foi encontrado. Foram selecionados 28 artigos, os quais foram analisados na íntegra e descritos quanto ao número de participantes, o método, os instrumentos utilizados e outras variáveis mensuradas. Os resultados a respeito da relação entre coparentalidade e temperamento foram organizados em seis categorias. Apenas dois artigos apontaram a não existência de relações significativas entre as duas variáveis. Destaca-se que a maioria dos artigos indicou o temperamento como preditor da coparentalidade, bem como o papel moderador da coparentalidade enquanto fator de risco e proteção. As relações bidirecionais entre as variáveis foram abordadas em apenas três artigos e questiona-se a escassez de estudos nessa direção. As diferenças na coparentalidade de pais e mães apontam para a importância das discussões sobre gênero.

Palavras-chave: Coparentalidade, temperamento, revisão sistemática.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de esta revisión fue analizar los estudios empíricos que midieron temperamento y coparentalidad. Para ello, se buscó responder a la pregunta "¿cuál es la relación entre las variables coparentalidad y temperamento en estudios empíricos, considerando los diferentes enfoques teóricos, los diferentes instrumentos utilizados y familias con niños entre cero y 11 años?". Las bases de datos elegidas para esta revisión fueron BVS-PSI, Psycinfo, Pubmed, Scopus e Web of Science. La base de datos BVS-PSI fue investigada, pero no se encontró ningún artículo. Se seleccionaron 28 artículos, los cuales fueron analizados en la integración y descritos en cuanto al número de participantes, el método, los instrumentos utilizados y otras variables mensuradas. Los resultados sobre la relación entre coparentalidad y temperamento se organizaron en seis categorías. Sólo dos artículos apuntaron a la no existencia de relaciones siginificativas entre las dos variables. Se destaca el mayor número de artículos que apuntan al temperamento como predictor de la coparentalidad y el papel moderador de la coparentalidad como factor de riesgo y protección. Las relaciones bidireccionales entre las variables se abordaron en sólo tres artículos y se cuestiona la escasez de estudios en esa dirección. Las diferencias en la coparentalidad de padres y madres apuntan a importancia de las discusiones sobre género.

Palabras clave: Coparentalidad, temperamento, revisión sistemática.

The family context, a space in which the child's first experiences of socialization and learning take place, plays a fundamental role in childhood development (Dessen & Braz, 2005; Linhares, 2015). In this initial process of socialization, the family, regardless of its con-figuration, contributes to the construction of the child's identity, helping to develop both the sense of belonging to the family group and the sense of individuation/differentiation (Minuchin, 1982).

The child, with its individual characteristics, including temperament, responds to the surrounding family environment and provokes some reaction in it. Thus, part of the systemic premise is that family relationships are based on recursive causalities (Vasconcellos, 2005). Minuchin (1982), in turn, portrayed the interrelationship and interdependence between the family subsystems.

The division of the family system into subsystems (fraternal, marital, parental/executive), as Minuchin (1982) proposes, is interesting not only from a didactic point of view, but also to differentiate the functions and roles within the family. Although the marital and parental/executive subsystems are interrelated, they have clear differences (Gadoni-Costa, Frizzo, & Lopes, 2015). The definition of parental/executive subsystem introduces what we now call coparenting, since both refer to the interaction of two adults in the guidance, upbringing, and fulfillment of the needs of the children (Lamela, Nunes-Costa, & Figueiredo, 2010). The theoretical origin of coparenting comes not only from Minuchin's (1982) structural theory, but also from Weissman and Cohen's (1985) theory of object relationships, which, through the concept of parental alliance, addresses how parents are involved and work together to raise children (Souza et al., 2017).

The contemporary concept of coparenting, in turn, has its main exponents in the theoretical models of Feinberg (2003), Margolin, Gordis, and John (2001) and McHale (1997). The authors differ in aspects of concept definition, in the dimensions and in the measurement of the construct through means of different instruments. Coparenting for McHale (1997) is understood from four factors: family integrity, disparagement, conflict, and reprimand. For Margolin et al. (2001), the construct is understood through the analysis of three dimensions: conflict, cooperation and triangulation. The Model of the Internal Structure and Ecological Context of Coparenting of Feinberg, in turn, was constructed based on pre-existing models (Feinberg, 2003). This author defines the internal structure of coparenting with four-dimensional: agreement/disagreement between the parental pair, division of labor, support/undermining of the parental role of the partner, and joint management of the family interactions. The Ecological Context of Coparenting is formed by all the aspects that mediate, influence and are influenced by the coparenting, that is, the individual characteristics of the children (such as temperament) and parents, the parenting, and the extra-family relationships.

Research on coparenting is more recent, especially when compared to studies of conjugality and parenting. Even so, studies have already demonstrated that the quality of coparenting may more consistently explain the developmental trajectory of the children than the marital and parental quality studied individually (Lamela et al., 2010).

The temperament of the child is among the aspects of child development that have been related to coparenting (Feinberg, 2002, 2003; Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, 2008; Lamela et al., 2010; Teubert & Pinquart, 2010). Some studies suggest the influence of coparenting on temperament, while the majority indicate the impact of temperament on coparenting. For example, a child with a difficult temperament may collaborate to increase stress and conflict within the coparental relationship because of the difficulties encountered in the routine with the child (Feinberg, 2003).

Temperament is conceived as the individual differences of constitutional basis related to reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart, 1981; Rothbart, Ellis, & Posner, 2004). According to a systematic review by Klein and Linhares (2010), four approaches to the study of temperament have been highlighted: Buss and Plomin (1984), Kagan (1998), Rothbart (1981) and Thomas and Chess (1977). Results of this review indicated that the psychobiological approach of Rothbart (1981 is the most used in the study of child temperament. It stands out due to evaluating temperament throughout development and due to understanding the influence of heredity, maturation, and experience. In this approach, temperament includes three major factors: (1) extroversion: defined by impulsivity, activity level, high intensity pleasure and shyness; (2) negative affect: characterized by fear, anger/frustration, sadness, discomfort, ability to calm down; and (3) effortful control: inhibitory control, attention focus, low intensity pleasure and perceptual sensitivity (Rothbart et al., 2004).

In relation to coparenting and temperament, the studies present distinct designs, based on one of the theoretical approaches and, consequently, the instruments used to measure the constructs vary from one study to another. The dimensions analyzed for both also change, leading to different analyses and results. Other variables, such as marital satisfaction (Favez, Frascarolo, Lavanchy Scaiola, & Corboz-Warnery, 2013), parenting (Karreman et al., 2008) and the child's behavior (Schoppe-Sullivan, Weldon, Cook, Davis, & Buckley, 2009) are measured in studies, being related to coparenting and temperament or appearing as mediators or moderators.

This variability of studies, theoretical approaches, instruments and results, coupled with the importance of the themes of coparenting and temperament for research on child development, justifies a systematic review with the aim of verifying which empirical studies have measured temperament and coparenting in the period from the birth of the child to school age. In addition, the intention was to describe how the variables were analyzed in the articles selected, the point of the life cycle of the research participants, the methods were used and the main results presented.

To achieve the proposed objective, the guiding question for this review was: What is the relationship between the variables coparenting and temperament in empirical studies, considering the different theoretical approaches and the different instruments used in families with children between zero and 11 years of age? Accordingly, the study proposes to systematize:

1. What methods and instruments are used to measure or characterize temperament?

2. What methods and instruments are used to measure or characterize coparenting?

3. What are the main variables that moderate or interfere in the relationship between coparenting and temperament?

4. What is the reported relationship between these two estimated variables?

Method

For this systematic review, the PRISMA recommendations were adopted (Liberati et al., 2009). For the inclusion of articles, the following criteria were delineated: empirical articles that used any instrument (questionnaire, scale, observation protocol) to measure temperament and coparenting; with samples of two-parent families; with children from zero to 11 years of age. The exclusion criteria were: theoretical studies; qualitative approach; sample of binuclear and single-parent families; adolescent children; studies that evaluated only one of the constructs and those that measured, but did not relate the two constructs. These criteria were chosen because it is understood that there are particularities in two-parent, binuclear and single-parent families, which can influence the results and generate other discussions.

The databases chosen for the review were: VHL-Psi, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. The search was conducted in April 2017 and there was no time delimitation. All articles that dealt with the variables temperament and coparenting were selected. The descriptors used were: coparenting AND temperament OR parenting alliance AND temperament OR interparental relationship AND temperament OR interparental conflict AND temperament.

Results

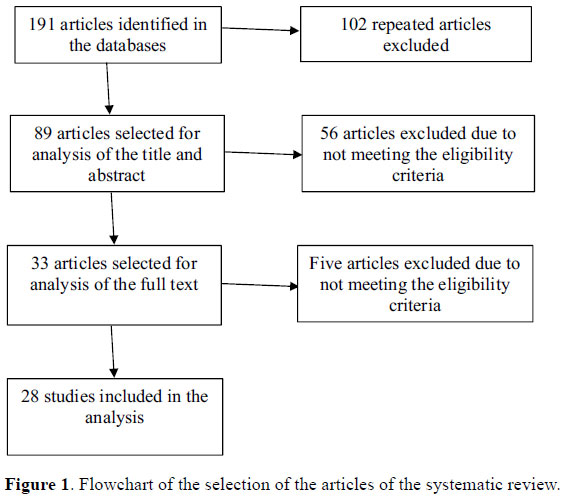

A total of 191 articles were initially retrieved: 61 in PsycINFO, 33 in PubMed, 43 in Scopus and 54 in the Web of Science. No articles were found in the Brazilian VHL-Psi database. Excluding duplicate articles, 89 remained. Of these, 61 were excluded because they did not fulfill the criteria described above. Of the excluded articles: eight were theoretical; one had a qualitative approach; seven articles only dealt with coparenting; 29 only focused on temperament; three addressed binuclear families and two had samples of families with adolescents; eight did not include the themes studied; and in three coparenting and temperament were measured, however, the analyses did not include the relationship between the two. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the search and selection performed.

In order to give greater reliability to the data of this review, a second researcher followed the same steps for the search and after the collation, agreement was verified regarding the articles selected. Information was extracted from the 28 articles related to the participants, methods, instruments used and other variables measured in the studies. This data is described in the characterization section. The results of the searches that highlight the relationship between coparenting and temperament were systematized with the organization into categories and presented in the thematic analysis section.

Characterization

Participants (families and age of the children). The participants in the majority of the studies were fathers and mothers. In two of the studies the participants were exclusively mothers. The sample of the studies performed exclusively with mothers ranged from 100 to 200 mothers. Of the other studies, 12 had a sample ranging from 50 to 100 fathers and mothers; seven studies had between 100 and 150 fathers and mothers; one study had between 150 and 200; and in another two the sample was 25 to 50 fathers and mothers. In four studies the sample was over 200 with a maximum of 359 fathers and mothers.

Regarding the age of the children, all the studies worked with families with children between zero and five years of age. In 13 studies the children were aged between zero and three years. The nine longitudinal studies that worked with families from the prenatal care formed another relevant group. Four studies were also highlight that dealt with the transition to siblinghood, with the first collection when the first child was between one and five years of age and the mother was in the third trimester of pregnancy with the second child, and the final collection at 12 months of age of the second child.

Methods. In 21 studies, the phenomena were accessed through direct (in the laboratory or natural setting) and indirect (questionnaires and scales) observation. The most expressive group was composed of 16 articles with longitudinal cohorts and direct and indirect observation. Among the others, seven were longitudinal and used only indirect observation, while five had a cross-sectional cohort with direct and indirect observation.

Instruments for measuring coparenting. Among the self-report questionnaires and observation measures, 19 different coparenting instruments were used, four of which were constructed or adapted for the studies. Some studies used more than one instrument to measure the construct, seven of which used a questionnaire and observation of the coparenting. For the observation of the coparenting behavior, the most used instrument was the Coparenting Behavior Coding Scales by Cowan and Cowan (1996), used in five studies. In addition, three studies used the Coparenting and Family Rating System, CFRS, by McHale (1997). The most used self-report questionnaire was the Coparenting Relationship Scale, CRS (Feinberg, Brown, & Kan, 2012), used in four studies.

Instruments for measuring temperament. To measure temperament, 10 different instruments were used, with three standing out as the most frequent. The Infant Characteristics Questionnaire, ICQ (Bates, Freeland, & Lounsburry, 1979), appeared in 10 studies; The Infant Behavior Questionnaire, IBQ (Garstein & Rothbart, 2003; Rothbart & Gartstein, 2000), for children between 3 and 12 months of age, in seven studies; and the Child Behavior Questionnaire, CBQ (Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001) for children aged 3 to 7 years, was used in seven studies. The IBQ and CBQ are based on the psychobiological approach of Rothbart, differ in the specificity of the age groups and are parental reports regarding the temperament of their children.

Other variables measured. In addition to coparenting and child temperament, 29 other variables were measured in the studies selected. Some of these variables were present in several articles, such as parenting, which appeared in 14 studies, marital satisfaction in five, and child behavior in four.

Thematic Analysis of the Relationship between Child Temperament and Coparenting

With the characterization of the studies selected, the variability of method, instruments, participants and other variables used in the 28 articles was evident. This variability, together with the different aims of the studies, resulted in very different findings. To better comprehend these findings, six thematic groups were created based on the similarity of the results. The groups are presented and defined in table 1 and the main results are reported in sequence.

Temperament as a predictor of copa-renting. A total of nine articles indicated temperament as a predictor of coparenting. The study of Burney (2010) examined two dimensions of child temperament, negative affect, and effortful control. The results demonstrated that both negative affect and effortful control were significant predictors of the maternal perception of the coparenting. Mothers that perceived their children as having more negative affect reported less positive coparenting, while the mothers that evaluated their children with more effortful control reported more positive coparenting relationships.

The study by Laxman et al. (2013) analyzed the personalities of the parents and temperament of the child, which were associated with stability of the coparenting in the first three years of the child's life. The findings indicated moderate coparenting stability and the child's difficult temperament were associated with less supportive coparenting. The results of the study by Favez et al. (2013) indicated that prenatal interactions and temperament were the main predictors of the coparenting relationships.

The study by Lindsey et al. (2005) examined social support, child temperament, parental self-esteem, care beliefs, and coparenting behavior. The results of regression analyses indicated that social support, parental self-esteem and the child's temperament were significantly related to coparenting behavior. Specifically, parents of children with a difficult temperament demonstrated more intrusive coparenting behavior.

It is important to highlight that, in some studies, the relationship between temperament and coparenting of the fathers presented differences from the relationship between temperament and coparenting of the mothers (Gordon & Feldman, 2008; Kuo et al., 2017; Van Egeren, 2004). In the study by Gordon and Feldman (2008) the temperament of the child, marital satisfaction and the relational behavior of the mother were predictors of the paternal coparenting behavior, while for the maternal coparenting only the father's relational behavior appeared to be a predictor.

The study by Kuo et al. (2017) explored coparenting after the birth of the second child. The results indicated that the difficult temperament of the first child was positively related to conflictive coparenting of the fathers and mothers and negatively with cooperative coparenting in the prenatal period and at 4 months. In addition, the mothers, but not the fathers, engaged in more conflictive coparenting when both the first and second child had difficult temperaments.

In the study by Van Egeren (2004), in turn, the child's temperament was only a predictor of the paternal coparenting behavior. Fathers reported a better experience of coparenting when their infants had easy temperaments, and fathers who perceived their babies as more difficult had worse coparenting relationships (Van Egeren, 2004).

The moderating role of coparenting, temperament, and other variables. The study by Kolak and Volling (2013) examined the contribution of temperament (negative reac-tivity) and coparenting to the internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems of the child after the birth of a sibling. The results indicated that negative reactivity in children is associated with an increase in externalizing behavior during the transition to siblinghood when parents showed high levels of undermining coparenting and low levels of supportive coparenting. Negative reactivity in children was also associated with increased internalizing behaviors when their parents had high undermining coparenting in the prenatal period. There was no association between negative reactivity and internalizing problems when undermining coparenting was low. It is considered, therefore, that the coparenting acted as a moderator of the relationship between negative reactivity and internalizing problems, affecting the outcome.

In the study by Schoppe-Sullivan et al. (2009), coparenting also had a moderating role. The results showed that supportive coparenting behavior moderated longitudinal relationships between the effortful control dimension of the children and the reports of externalizing behavior reported by both mothers and teachers. That is, when the parents showed high levels of supportive coparenting behavior, the relationship between low effortful control and externalizing behavior was not observed.

Supportive coparenting moderated relation-ships between the temperament of the child and depressive symptoms of the parents in the study by Solmeyer and Feinberg (2011). In parents reporting low supportive coparenting, there was a positive association between difficult temperament and depressive symptoms. In parents that reported more supportive coparenting, the temperament of the child was not shown to be associated with depressive symptoms of the parents. Thus, supportive coparenting had a buffer effect on the child's negative temperament and depressive symptoms of the parents.

The study by Szabó et al. (2012) analyzed the stability of the coparenting and its relationship with the temperament of the child in the transition to siblinghood. The findings suggested stability of the coparenting with child 1, however, this stability was moderated by the difficult temperament of child 2. That is, the coparenting remained stable after the arrival of the second child only when child 2 had an easy temperament. When child 2 had a difficult temperament, the quality of the coparenting varied. These results were obtained by relating the measures of the coparenting questionnaire to the temperament of the child. The measures of observation of the coparenting did not present significant relationships with the temperament of children 1 and 2.

In the study by Schoppe-Sullivan et al. (2007), the variable quality of the marital relationship moderated the relationship between temperament and coparenting. Specifically, challenging infants were associated with low levels of undermining coparenting when the couples presented high marital quality prior to the birth of the infant. The difficulty of adaptation in infants was associated with high levels of undermining coparenting, when the couples presented low marital quality prior to the birth of the infant.

The results of the study by Burney and Leerkes (2010) indicated that the reactivity dimension of the temperament was associated with a reduction in the quality of the coparenting only when other "stressors" were present. Mothers that perceived their infants as more reactive reported more negative coparenting only when their infants were not easily calmed or when the mothers were dissatisfied with the division of the parenting tasks. The fathers reported more negative coparenting when their infants were more reactive and they had reported low quality in the marital relationship.

Bidirectional relationships between coparenting and temperament. Two-way relationships between temperament and copa-renting were found in two studies that speci-fically addressed the relationship between child temperament and coparenting behavior in the first year of life of infants (Davis et al., 2009; LeRoy, 2013). The results of the study by Davis et al. (2009) showed that infants with difficult temperaments were associated with less supportive coparenting behavior. Likewise, supportive coparenting was associated with a decrease in the difficult temperament of the infants. The study by LeRoy (2013) measured temperament with the dullness, unadaptability, unpredictability and fussiness dimensions and revealed the existence of a bidirectional relationships between the dimensions of the child's temperament and the coparenting throughout the child's first year of life. These results emerged specifically from analyses of coparenting questionnaires answered by the parents. No significant results emerged from the predictive models of maternal coparenting, with there being no association between the temperament variables and the observational measures of the coparenting.

Another study that highlighted the bidirec-tional relationships between these variables was that of Song and Volling (2015), who examined how the coparenting and temperament of the first child influenced the cooperative behavior after the birth of a sibling. The results demonstrated the significant bidirectional interaction between the sensitivity dimension of the temperament and cooperative coparenting, as well as interactions between sensitivity, cooperative coparenting and undermining coparenting.

Coparenting as a predictor of tempe-rament and its greater influence than that of parenting. The first study that related the coparenting variables and temperament was that of Belsky et al. (1996). The authors specifically addressed the unsupportive coparenting behavior and the inhibition dimension of the child's temperament. As a result it was found that unsupportive coparenting was related to less inhibition. Another important aspect in the article was that the coparenting predicted inhibition in children more than the measures of parenting alone, that is, coparenting influences inhibition more than parenting.

The study by Karreman et al. (2008) dealt with the relationships between parenting, coparenting and the effortful control dimension in preschool children. The results indicated coparenting as a predictor of effortful control, over and above maternal and paternal parenting. In addition, coparenting was significantly related to effortful control, both through observation and through the questionnaire.

Coparenting and temperament did not present relationships. In only two articles the variables coparenting and temperament did not present any significant relationship. The study by Stright and Bales (2003) related the characteristics of the children and parents and the quality of the coparenting during observation of family interactions. The temperament of the child was not related to support or to the lack of support in the coparenting. In the study by Favez et al. (2016) the evaluations that parents made of the child's temperament were not related to the coparenting interactions.

Temperament and coparenting were related. Some studies indicated the correlation between temperament and coparenting. The study by Metz et al. (2016) examined the rela-tionships between the dimensions of supportive and undermining coparenting and the fearful temperament dimension in predictive and concurrent analyses. A concurrent association was found, that is, when the fearful temperament and undermining coparenting were measured at the same time. However, no predictive relationships were found, when the fearful temperament was measured previously and undermining coparenting behavior subsequently.

When investigating the role of coparenting in the stability of the childhood temperament in the first 15 months of the infants' lives (0-3, 8, and 15 months), Rogowicz's (2016) study indicated a significant relationship between negative coparenting and children with difficult temperaments in the early months postpartum. However, this relationship between negative coparenting and the difficult temperament of the child was not identified when the child was eight months of age.

Discussion

This systematic review sought to analyze the results found in empirical articles that inves-tigated the relationship between the variables coparenting and childhood temperament. By means of the categorical analysis that was carried out, the existence was evident of significant relationships between the temperament and coparenting variables, since only two articles did not present the expected relationships. It should be highlighted that the samples of these two articles, of 40 (Stright & Bales, 2003) and 69 families (Favez et al., 2016), were smaller than the majority of the other studies selected.

The majority of the studies indicated tem-perament as a predictor of coparenting. Feinberg (2003), in his model of Internal Structure and Ecological Context, also suggested the influence of temperament, as an individual characteristic of the child, on coparenting. Likewise, the moderating role of coparenting as a risk and protection factor was problematized by Feinberg (2003) and appears in three articles in this review. The findings corroborate the theory by highlighting, for example, that supportive coparenting moderated relationships between the temperament of the child and depressive symptoms of the parents (Solmeyer & Feinberg, 2011).

It was noted, however, that only three articles presented a design in which it was possible to observe the bidirectional relationship between coparenting and the child's temperament. Although the majority of the studies mentioned the systemic theory, as well as Minuchin's (1982) structural theory, which understands subsystems as interdependent and interrelated, the data were analyzed in a single direction. According to the systemic theory, a possible comprehension would be of a recursive causal relation that is not exactly bidirectional. However, in the quantitative study, bidirectionality is what most resembles this understanding.

Another aspect evidenced was how temperament influences the coparenting of fathers and mothers differently. While in the studies of Gordon and Feldman (2008), LeRoy (2013) and Van Egeren (2004), paternal coparenting behavior was more sensitive to influences of the child's temperament, in the study of Kuo et al. (2017), it was the maternal coparenting that was influenced by the temperament. The discrepancy in the results may be related to the fact that the studies addressed different aspects of coparenting and temperament. In addition, fathers and mothers engage in different ways in caring for their children according to the characteristics of each child and also the social and cultural transformations (Bossardi, 2011). Although fathers are increasingly involved in caring for children, mothers generally spend more time with their children and have more responsibility for the daily care (Bossardi & Vieira, 2015), which can help to make them more or less sensitive to the temperament characteristics of the children.

Regarding the methods used by the authors, it should be highlighted that in seven studies, both direct observation and questionnaire measures were used to evaluate the coparenting. The combination of more than one form of obtaining data, such as direct observation, whether in the laboratory or in the natural setting, and indirect observation with the application of questionnaires, is understood to be an important strategy due to the complexity of the psychological phenomenon in question, which is coparenting. With the diversity of methodologies used in the study of coparenting and temperament, it was possible to verify congruent results and others that differed in highlighting or amplifying different aspects of the relationship of these variables.

The majority of the studies presented a longitudinal cohort, and consequently family monitoring over a period of time, which made it possible to predict whether there were changes in the coparenting due to the child's temperament and changes in the temperament due to the coparenting. The transition to coparenting was the period chosen in several articles. This is a phase of intense changes in the family routine, which was previously formed by the couple alone and needs to be renegotiated to include the child in the relationship (Carter & McGoldrick, 1995). The age range in the majority of the studies was of children between the ages of zero and five years, an initial period of development, in which the evaluation of the dispositional and constitutional traits (Linhares, Dualibe, & Cassiano, 2013) is interesting and in which the parents are also adapting to the new phase.

Finally, the findings of this review allow a reflection on the clinical practice with families. The coparenting relationship is an important point to be observed and worked on by psychologists and family therapists, since the quality of this relationship contributes to various aspects of the child's development, among them, the temperament. Similarly, working with parents regarding the individual differences of each child and how to deal with them, is presented as a perspective of the quality of the family relationship.

Limitations of the Study

Although it is understood that the database search by means of the general constructs, temperament and coparenting, allows more precise access to the articles, it is considered that not including the dimensions (e.g. undermining coparenting, supportive coparenting, negative affect, effortful control) as descriptors may have been a limitation of this systematic review. It should be emphasized that the fact that there are no national publications on the relationship between the two variables highlights the importance of carrying out studies that relate them, given the relevance of the themes for research in the area of child development and family relationships.

Future Studies

The performance of future studies in Brazil and Latin America is recommended to investi-gate whether there are idiosyncrasies for these samples, to explore new variables associated with temperament and coparenting, and to elaborate studies that address gender differences and that include older children, since in the majority of studies the children ranged from zero to three years. In addition, a meta-analysis is suggested, since a quantitative analysis of the results of the studies could provide more precise answers regarding the relationships between coparenting and temperament.

References

Bates, J. E., Freeland, C. A. B., & Lounsbury, M. L. (1979). Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Development, 794-803. [ Links ]

*Belsky, J., Putnam, S., & Crnic, K. (1996). Coparenting, parenting, and early emotional development.New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1996(74),45-55. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219967405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219967405 [ Links ]

Bossardi, C. N. (2011). Relação do engajamento parental e relacionamento conjugal no investimento com os filhos (Master's thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil). [ Links ]

Bossardi, C. N., & Vieira, M. L. (2015). Ser mãe e ser pai: Integração de fatores biológicos e culturais. In E. Goetz & M. L. Vieira (Eds.), Novo pai: Percursos, desafios e possibilidades (pp. 15-30). Curitiba, PR: Juruá [ Links ].

*Burney, R. V. (2010). Links between temperament and coparenting: The moderating role of family characteristics (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis. (UMI Number: 3434127) [ Links ]

*Burney, R. V., & Leerkes, E. M. (2010). Links between mothers' and fathers' perceptions of infant temperament and coparenting. Infant Behavior & Development, 33(2),125-135. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.12.002 [ Links ]

Buss, A. H., & Plomin, R. (1984). Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Carter, B., & McGoldrick, M. (1995). As mudanças no ciclo de vida familiar: Uma estrutura para a terapia familiar. In B. Carter & M. McGoldrick (Eds.), As mudanças no ciclo de vida familiar: Uma estrutura para a terapia familiar (pp. 7-29). Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. [ Links ]

*Cook, J. C., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Buckley, C. K., & Davis, E. F. (2009). Are some children harder to coparent than others? Children's negative emotionality and coparenting relationship quality. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(4),606-610. doi: 10.1037/a0015992 [ Links ]

Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (1996). Schoolchildren and their families project: Description of co-parenting style ratings. Unpublished coding scales, University of California, Berkeley. [ Links ]

*Davis, E. F., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Brown, G. L. (2009). The role of infant temperament in stability and change in coparenting across the first year of life. Parenting: Science and Practice, 9(1-2),143-159. doi: 10.1080/15295190802656836. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15295190802656836 [ Links ]

Dessen, M. A., & Braz, M. P. (2005). A família e suas inter-relações com o desenvolvimento humano. In M. A. Dessen & A. L. Costa Junior (Eds.), A ciência do desenvolvimento humano: Tendências atuais e perspectivas futuras (pp. 113-131). Porto Alegre, RS: Artes Médicas. [ Links ]

*Favez, N., Frascarolo, F., Lavanchy Scaiola, C., & Corboz-Warnery, A. (2013). Prenatal representations of family in parents and coparental interactions as predictors of triadic interactions during infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34(1),25-36. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21372 [ Links ]

*Favez, N., Tissot, H., & Frascarolo, F. (2016). Parents representations of mother's child and father's child relationships as predictors of early coparenting interactions. Journal of Family Studies, 1-15. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2016.1230511. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2016.1230511 [ Links ]

Feinberg, M. E. (2002). Coparenting and the transition to parenthood : A framework for prevention. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(3),173-195. doi: 10.1023/A:1019695015110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1019695015110 [ Links ]

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2),1-30. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327922PAR0302 [ Links ]

Feinberg, M. E., Brown, L. D., & Kan, M. L. (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting.Parenting, 12(1),1-21. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.638870.A. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2012.638870.A [ Links ]

Gadoni-Costa, L. M., Frizzo, G. B., & Lopes, R. C. S. (2015). A guarda compartilhada na prática: Estudo de casos múltiplos.Temas em Psicologia, 23(4),901-912. doi: 10.9788/TP2015.4-08. http://dx.doi.org/doi: 10.9788/TP2015.4-08 [ Links ]

*Galdiolo, S., & Roskam, I. (2016). From me to us: The construction of family alliance. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(1),29-44. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21543 [ Links ]

Gartstein, M. A., & Rothbart, M. K. (2003). Studying infant temperament via the revised infant behavior questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development, 26(1),64-86. [ Links ]

*Gordon, I., & Feldman, R. (2008). Synchrony in the triad: A microlevel process model of coparenting and parent‐child interactions.Family Process, 47(4),465-479. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00266.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00266.x

Kagan, J. (1998). Biology and the child. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol. 3, pp. 177- 235). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

*Karreman, A., van Tuijl, C., van Aken, M. A. G., & Deković, M. (2008). Parenting, coparenting, and effortful control in preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1),30-40. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.30

*Kim, B. R., & Teti, D. M. (2014). Maternal emotional availability during infant bedtime: An ecological framework. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(1),1-11. doi: 10.1037/a0035157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0035157 [ Links ]

Klein, V., & Linhares, M. (2010). Temperament and child development: Systematic review of the literature. Psicologia em Estudo, 15(4),821-829. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1413-73722010000400018&script=sci_arttext&tlng=es [ Links ]

*Kolak, A. M., & Volling, B. L. (2013). Coparenting moderates the association between firstborn children's temperament and problem behavior across the transition to siblinghood. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(3),355-364. doi: 10.1037/a0032864. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0032864 [ Links ]

*Kuo, P. X., Volling, B. L., & Gonzalez, R. (2017). His, hers, or theirs? Coparenting after the birth of a second child. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(6),710-720. doi: 10.1037/fam0000321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fam0000321 [ Links ]

Lamela, D., Nunes-Costa, R., & Figueiredo, B. (2010). Theoretical models of coparenting relations: Critical review. Psicologia em Estudo, 15(1),205-216. doi: 10.1590/S1413-73722010000100022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722010000100022 [ Links ]

*Laxman, D. J., Jessee, A., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Rossmiller-Giesing, W., Brown, G. L., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2013). Stability and antecedents of coparenting quality: The role of parent personality and child temperament. Infant Behavior & Development, 36(2),210-222. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.01.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.01.001 [ Links ]

*LeRoy, M. (2013). Predictors of coparenting: Infant temperament, infant gender, and hostile-reactive parenting (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis. (UMI Number: 3671438) [ Links ]

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., ...Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Expla-nation and elaboration.PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [ Links ]

*Lindsey, E. W., Caldera, Y., & Colwell, M. (2005). Correlates of coparenting during infancy. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 54(3),346-359. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00322.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00322.x [ Links ]

Linhares, M. B. M. (2015). Família e desenvolvimento na primeira infância: Processos de autorregulação, resiliência e socialização de crianças pequenas. In G. A. Pluciennik, M. C. Lazzari, & M. F. Chicaro (Eds.), Fundamentos da família como promotora do desenvolvimento infantil: Parentalidade em foco (pp. 70-83). São Paulo, SP: Fundação Maria Cecília Souto Vidigal. [ Links ]

Linhares, M. B. M., Dualibe, A. L., & Cassiano, R. G. M. (2013). Temperamento de crianças na abordagem de Rothbart: Estudo de revisão sistemática. Psicologia em Estudo, 18(4),633-645. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pe/v18n4/06.pdf [ Links ]

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & John, R. S. (2001). Coparenting : A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1),3-21. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.3 [ Links ]

*McDaniel, B. T., & Teti, D. M. (2012). Coparenting quality during the first three months after birth: The role of infant sleep quality. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(6),886-895. doi: 10.1037/a0030707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0030707 [ Links ]

McHale, J. P. (1997). Overt and covert coparenting processes in the family. Family Process, 36(2),183-201. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00183.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00183.x [ Links ]

*Merrifield, K. A., Lucero-Liu, A. A., & Gamble, W. C. (2014). Coparenting in families of Mexican descent: Exploring stability, antecedents, and typologies. Marriage & Family Review, 50(6),505-532. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2014.909915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2014.909915 [ Links ]

*Metz, M., Majdandžić, M., & Bögels, S. (2016). Concurrent and predictive associations between infants' and toddlers' fearful temperament, coparenting, and parental anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 1-12. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1121823. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1121823

Minuchin, S. (1982). Famílias: Funcionamento e tratamento. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. [ Links ]

*Rogowicz, S. (2016). The impact of the coparenting relationship in heterosexual couples on the stability of infant difficult temperament (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis. (UMI Number: 366254) [ Links ]

Rothbart, M. K. (1981). Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child Development, 52,569-578. doi: 10.2307/1129176. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1129176 [ Links ]

Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., & Hershey, K. L. (1994). Temperament and social behavior in childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, (1982-),21-39. [ Links ]

Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., Hershey, K. L., & Fisher, P. (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72(5),1394-1408. [ Links ]

Rothbart, M. K., Ellis, L., & Posner, M. (2004). Temperament and self regulation. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 357-370). New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Rothbart, M. K., & Gartstein, M. A. (2000). Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised: Items by Scale. University of Oregon. [ Links ]

*Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Weldon, A. H., Cook, J. C., Davis, E. F., & Buckley, C. K. (2009). Coparenting behavior moderates longitudinal relations between effortful control and preschool children's externalizing behavior. Journal Child Psychology Psychiatry, 50(6),698-706. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02009.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02009.x [ Links ]

*Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Brown, G. L., & Szewczyk Sokolowski, M. (2007). Goodness-of-fit in family context: Infant temperament, marital quality, and early coparenting behavior. Infant Behavior and Development, 30(1),82-96. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.008 [ Links ]

*Smith-Simon, K. E. (2008). Coparenting across early childhood: Influences on the development of internalizing symptoms (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis. (UMI Number: 3285001) [ Links ]

*Solmeyer, A. R., & Feinberg, M. E. (2011). Mother and father adjustment during early parenthood: The roles of infant temperament and coparenting relationship quality. Infant Behavior & Development. 34(4),504-514. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.006 [ Links ]

*Song, J.-H., & Volling, B. L. (2015). Coparenting and children's temperament predict firstborns' cooperation in the care of an infant sibling. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(1),130-135. doi: 10.1037/fam0000052. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fam0000052 [ Links ]

Souza, C. D. de, Sabbag, G., Portes, J. R. M., Barreto, M., Cruz, R. M., & Vieira M. L. (2017) Coparentalidade: Análise de propriedades psicométricas de escalas e questionários. In L. Moreira & E. Rabinovich, Pais, avós e relacionamentos intergeracionais na família contemporânea. Curitiba, PR: CRV. [ Links ]

*Stright, A. D., & Bales, S. S. (2003). Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Family Relations, 52(3),232-240. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00232.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00232.x [ Links ]

*Szabó, N., Dubas, J. S., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2012). And baby makes four: The stability of coparenting and the effects of child temperament after the arrival of a second child. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(4),554-564. doi: 10.1037/a0028805. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0028805 [ Links ]

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(4),286-307. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2010.492040. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2010.492040 [ Links ]

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. New York: Brunner/Mazel. [ Links ]

*Van Egeren, L. A. (2004). The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal, 25(5),453-477. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20019 [ Links ]

Vasconcellos, M. L. E. de (2005). Pensamento sistêmico: O novo paradigma da ciência (4th Ed.). Campinas, SP: Papirus. [ Links ]

Weissman, S., & Cohen, R. (1985). The parenting alliance and adolescence. Adolescent Psychiatry, 12,24-45. [ Links ]

Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Monica Barreto

Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Departamento de Psicologia

Campus Reitor João David Ferreira Lima, s/n - Trindade

Florianópolis, SC, Brasil 88040-900

Phone: (48) 3721-4989

E-mail: mobarreto.psi@gmail.com and maurolvieira@gmail.com

Received: 12/12/2017

1st revision: 19/04/2018

2nd revision: 15/08/2018

3rt revision: 08/01/2019

Accepted: 14/03/2019

Authors' Contributions:

Substantial contribution in the concept and design of the study: Monica Barreto

Contribution to data collection: Monica Barreto; João Paulo Koltermann.

Contribution to data analysis and interpretation: Monica Barreto; João Paulo Koltermann.

Contribution to manuscript preparation: Monica Barreto; João Paulo Koltermann; Mauro Luís Vieira.

Contribution to critical revision, adding intelectual content: Mauro Luís Vieira; Maria Aparecida Crepaldi.

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the publication of this manuscript.