Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho

ISSN 1984-6657

https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2017.4.13877

The occupational stress in International Business Travellers of a multinational of the automotive sector

O stress ocupacional em Viajantes de Negócios Internacionais de uma multinacional do setor automóvel

El estrés ocupacional en Viajeros de Negocios Internacionales en una multinacional del sector automotriz

Ana Rita Cardoso; Filomena Jordão

Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

ABSTRACT

International business travelers constitute an emerging type of international mobility, and there is a gap in terms of studies that address well-being. Based on the Holistic Model of Stress, we intend to explore the occupational stress associated with business travel through a qualitative case study using document analysis and semi-structured interviews. We verified a predominance of distress sources in the trip stage and the adoption of coping strategies focused on the problem. Personal and professional factors are assumed to be the main moderators of the stress experienced. We conclude that travel brings mostly negative personal consequences that are accentuated during the traveler's career, and confirm that the trips are a source of stress with impact on the personal and professional life of the traveler. The paper includes a discussion on the theoretical and practical implications of the findings for both the company and the travelers.

Keywords: International Business Travelers; Occupational Stress; Holistic Model of Stress.

RESUMO

Os Viajantes de Negócios Internacionais constituem uma modalidade de mobilidade internacional emergente, existindo uma lacuna ao nível de estudos que abordem o seu bem-estar. Com base no Modelo Holístico de Stress pretendemos explorar o stress ocupacional associado às viagens de negócios através de um estudo de caso qualitativo com recurso à análise documental e à entrevista semiestruturada. Foram predominantes as fontes de distress na fase da viagem e da adoção de estratégias de coping focadas no problema. Fatores pessoais e profissionais assumem-se como principais moderadores do stress percecionado. Concluímos que a viagem tem maioritariamente consequências pessoais e negativas que se acentuam ao longo da carreira do viajante e confirmamos que as viagens são uma fonte de stress com impacto na sua vida pessoal e profissional do viajante. O artigo incluí a discussão acerca das implicações teóricas e práticas dos resultados para a organização e para os viajantes.

Palavras-chave: Viajantes de Negócios Internacionais; Stress Ocupacional; Modelo Holístico do Stress.

RESUMEN

Los Viajeros de Negocios Internacionales constituyen una modalidad de movilidad internacional emergente, existiendo una laguna en el nivel de estudios que abordan su bienestar. Con base en el Modelo Holístico de Estrés pretendemos explorar el estrés ocupacional asociado a los viajes de negocios a través de un estudio de caso cualitativo, utilizando el análisis documental y la entrevista semiestructurada. Se verificó un predominio de fuentes de distress y la adopción de estrategias de coping enfocadas en el problema. Los factores personales y profesionales se asumen como principales moderadores del estrés percibido. Concluimos que el viaje tiene mayormente consecuencias personales y negativas, que se acentúan al través de la carrera de viajero. Confirmamos así que los viajes son una fuente de estrés con impacto en la vida personal y profesional. El artículo incluye la discusión sobre las implicaciones teóricas y prácticas de los resultados para la organización y para los viajeros.

Palabras clave: Viajeros de Negocios Internacionales; Modelo Holístico de Estrés; Estrés Ocupacional.

In an era characterized by globalization, the amount of companies involved in international markets has increased exponentially in order to act globally (Dobrai, Farkas, Karoliny, & Poór, 2012). The International Business Travellers (IBTs), characterized by frequent business travels of short-term to multiple countries are, precisely, a result of this climate of competition and continuous change (Welch, Welch, & Worm, 2007).

Nevertheless, the travels can imply costs to the travellers, either at the physical level and/or psychological (e.g., occupational stress) (DeFrank, Konopaske, & Ivancevich, 2000; Ivancevich, Konopaske, & DeFrank, 2003), given that there is still a gap in terms of studies that address the impact of the mobility requirements in the IBT well-being (Ivancevich, et al. 2003; Shaffer, Kraimer, Chen, & Bolino, 2012). Furthermore, some studies about international mobility suggest the analysis of the positive and negative impact of it on traveller's health (e.g., DeFrank et al., 2000; Mayerhofer, Hartmann, & Herbert, 2004; Westman, Etzion, & Chen, 2009). Per Ivancevich et al. (2003), "understanding the short and long-term effects of business travel can be very beneficial to managers and organizations as they attempt to maximize the positive outcomes of the travel" (p.139).

Then, we intend to explore the occupational stress associated with the business travels in the case of IBTs of a multinational company, based on the Holistic Model of Stress -HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007). Specifically, our research questions are: RQ1: What are the sources of occupational stress inherent to the business travels considering the phases of the travel; RQ2: How the IBT reacts to the sources of occupational stress; RQ3: What are the moderators of the occupational stress experienced for the IBT; RQ4: What are the professional and personal consequences of the travel; RQ5: How is the evolution of the occupational stress during the professional career.

Occupational stress

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, occupational stress has increased considerably (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a). Per Hart and Cooper (2001), this is a worldwide phenomenon, that results from the environment of constant change that we are living, which has high costs for the employees, the companies and, subsequently, the country's economy (Newton & Teo, 2014). The interest for this phenomenon is not recent. In the last decades, different authors attempted to understand stress from different perspectives (Beehr, 1995), generating several definitions and theories (Dewe, O' Driscoll, & Cooper, 2012).

Per Selye (1976), the stress is a non-specific response of the body to any demand of the context. There are two types of stress: the healthy one (eustress) and the pathogenic one (distress). Distress is a negative psychological response to a source of stress revealed by the presence of negative psychological states, while the eustress is a positive psychological response shown by the presence of positive psychological states (Simmons & Nelson, 2001).

Referring to the theories of stress, we can distinguish between explanatory and procedural models (Frese & Sonnentag, 2005), highlighting the HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007), a procedural model. This theory is based on the Transactional Model of Stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) that defines stress as arising from the cognitive evaluation that the subject makes of the situations and the resources that own to deal with them.

The majority of the studies focused on the causes of distress and the identification of coping strategies to deal with the stressors. Consequently, there is a gap in terms of studies that address the eustress causes and the identification of strategies to deal with those (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a). We considered that this gap is filled by the HMS that includes both, the positive and negative psychological responses, to the sources of stress.

Holistic model of stress

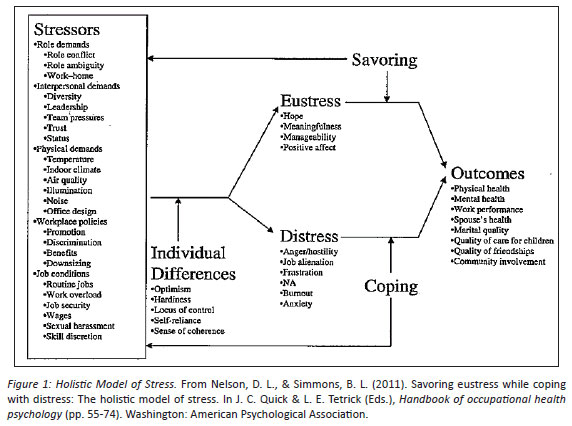

The HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007), presented in Figure 1, incorporates: several stressors; the positive (eustress) and the negative (distress) psychological responses to them; the management strategies of stress, savoring and coping; the personal characteristics as moderators of the responses; and, at last, the consequences of the stress management process at the personal and professional levels.

Sources of stress

The stressors are physical and psychological stimulus that produce a response from the subject (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a) and, per Cunha, Rego, Cunha, Cabral-Cardoso and Neves (2016) can be grouped in two categories: organizational and extra-organizational sources.

HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007) considers, primarily, organizational sources being that the extra-organizational factors are integrated, especially, through the role demands. Note that the authors expected that the majority of situations could lead to either eustress or distress responses, so we cannot simply assume the presence of eustress by the absence of distress, or the reverse.

Moderators of stress

Referring to the moderators of occupational stress we distinguished between contextual and individual characteristics (Cunha et al., 2016), being that in HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007) only this last were considered, namely: interdependence, self-esteem, optimism and pessimism, locus of control and hardiness.

Coping and savoring

The concept of coping appeared in the early 1970's Schaufeli (2015), distinguished three approaches to this concept: firstly, coping was studied from a psychodynamic approach, in analogy to the ego; secondly, coping was conceived as personality traits; and, currently, the dominant approach is the transactional originated from the works of Lazarus and Folkman (1987) that defined coping as "an effort that is independent from its success and includes proactive and defensive strategies" (Schaufeli, 2015, p. 7984). Here, we distinguish between two types of coping: one type focused on the problem and in its resolution; and another type focused on emotions, originated by the problem (Cooper, Dewe, & O'Driscoll, 2001).

As referred, HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007) introduced savoring, similar to coping, but for eustress. Bryant, Chadwick and Kluwe (2011) distinguished between four components of this construct: savoring experiences; processes, strategies and beliefs. According Nelson and Simmons (2003b) savoring means "enjoying something with appreciation or dwelling on it with great delight" (p. 313).

Consequences of the stress process

The consequences of the occupational stress are generally approached from the negative point of view (Cunha, Rego, Cunha, & Cabral-Cardoso, 2007). Quick and Henderson (2016), distinguished between three forms of distress: medical (e.g., heart disease, cancers); psychological (e.g., anxiety, depression); and behavioral (e.g., tobacco abuse, alcohol and drug abuse, violence). For the company, stress involves direct costs (e.g., increase of absenteeism, decrease in the work performance), and indirect costs (e.g., poor interpersonal relationships established in the work context, errors in decision-making) (Ramos, 2001).

Therefore, HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007) considered that the stress management process can have consequences at the following dimensions: physical and mental health, work performance, spouse's health, marital quality, quality of care for children, quality of relationships and community involvement. Note that the study of occupational stress has focused mainly on distress, so there is still a gap in terms of studies that address the consequences of eustress (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a).

International mobility

Globalization and international growth are now becoming central to all the competitive companies (Jensen, 2014), accentuating the need to establish relationships that allow them to work at a global level which requires, unavoidably, the mobility of employees.

It's well known within organizations that global mobility brings several benefits, namely: facilitates global business initiatives; drives expansion and growth; and, at last, develops high potential employees (Brookfield Global Relocation Services, 2016). Consequently, researchers have paid increasing attention to the effect of globalization on the management of employees across national boundaries (De Cieri, Fenwick, & Hutchings, 2005).

The study of global forms of employment is still recent and is increased in line with globalization (Mäkelä, Bergbom, Saarenpää, & Suutari, 2015). Therefore, it is not easy to describe and comprehend the various global work experiences that have recently emerged (Shaffer et al., 2012). Here, we opted for the taxonomy of global work experiences of Shaffer et al., (2012) that includes the traditional expatriate assignments and nontraditional corporate global alternatives of short-term, including IBTs.

The majority of studies about international mobility, including in the Portuguese context (Pinto, Cabral-Cardoso, & Werther, 2012), have focused on understanding the experiences of employees who are sent in long-term assignments and later their returning (Shaffer et al., 2012). Per Thomas and Lazarova (2006), the expatriate performance will depend on his adaptation to the new context, overlying his technical expertise. According to Pinto et al., (2012) the travel is, indeed, a personal investment. Consequently, it is a big challenge to deal with all the variables that influence the success of the expatriation (Shaffer et al., 2012) which lead companies to use alternative forms of global mobility. Note that although the research indicates an increase in the use of alternative forms of mobility, it does not indicate a decrease in the use of the expatriation (Mayerhofer, Hartmann, Michelitsch-Riedl, & Kollinger, 2004).

Alternative forms of international assignments

The IBTs is one of those alternative forms of global mobility next to short-term assignments and flexpatriates (Shaffer et al., 2012). Short-term assignments are no longer than three months and shorter than a year, including or not the relocation of the family (Collings, Scullion, & Morley, 2007; Mayerhofer et al., 2004; Shaffer et al., 2012); and flexpatriates travel for brief assignments, usually one or two months, not including the relocation of the family (Shaffer et al., 2012). Some authors consider also the virtual missions cause the work team is geographically dispersed and the several elements work for a common goal using technology (Collings et al., 2007; Erez et al., 2013).

International Business Travellers

According to PORDATA (2016), in 2015, 24% of the travels from Portugal to other countries had a business purpose. In fact, a survey carried out by Ernst and Young (2012) reveals that almost 60% of the companies expect an increase of business travels in the next years, rather than still opt for short or long-term assignments.

Per Welch et al. (2007), IBTs are employees for whom a huge part of their role involves international travels; in order to perform their job they travel frequently for short periods of time to multiple countries, without the necessity to move definitively to other country (Mayerhofer et al., 2004; Welch et al., 2007) or relocate their family (Meyskens, Von Glinow, Werther, Jr, & Clarke, 2009; Shaffer et al., 2012). The travel can lasts several days or weeks (Welch et al., 2007).

According to the taxonomy of global work experiences of Shaffer et al. (2012), international business travels have several purposes, without losing the contact with the home country: knowledge transfer, negotiation, discussion, participation in meeting or conferences (Shaffer et al., 2012), visits to foreign markets, units and projects (Welch et al., 2007). Consequently, the IBTs are employees that know deeply his organization and the way it works, having the power to inhibit or increase the national unit performance through the contact with the outside (Ramsey, Leonel, Gomes, & Monteiro, 2011). Nevertheless, DeFrank et al. (2000) recognize that the business travels can have several costs for the employee at the physical and psychological level of his health.

The perception of occupational stress in International Business Travellers

Through the traveller's exposure to new places, cultures and business practices and products the travel becomes very educational (DeFrank et al., 2000; Ivancevich et al., 2003). The learning opportunities produce positive emotions in the traveller (Westman & Etzion, 2002), which will have impact at the personal and professional level. At the personal level, the travel can lead to individual growth, making the IBT more aware about domestic and global issues (DeFrank et al., 2000).

Per DeFrank et al. (2000), despite all of the benefits, business travels can be challenging for the IBT too, involving psychical (e.g., fatigue and gastrointestinal problems) and/or psychological problems produced by the travel, the family separation, among other factors that can cause irritability and anxiety. Per Mäkelä, Saarenpää and McNulty (2017), the degree of travel-related stress depends on several factors (e.g., traveler's marital status).

DeFrank et al. (2000) defines the travel stress as "the perceptual, emotional, behavioral, and physical responses made by an individual to the various problems faced during one or more of the phases of travel" (p. 59). According to DeFrank et al. (2000), the pre-trip factors that can induce stress are the travel planning, the task delegation to be performed during the absence of the employee, and family-related activities. Travels seems to be harder for married employees and with children. In a study with Portuguese IBTs, some participants felt uncomfortable for being absent and/or suspending decisions to get married or have children due to their job (Pinto & Maia, 2015).

Regarding the stage of the travel, DeFrank et al. (2000) have highlighted factors such as the characteristics of the travel (e.g., duration, cancellation of flights), the travel logistics, the host country culture, the maintenance of a healthy lifestyle, and the importance and complexity of the task that led to mobility. Finally, at the post-trip, are highlighted factors as doubts concerning what happened in the national unit while IBT was absent and the return to the professional routine and to the family. That is especially evident in the case of women IBTs that combine their job with the motherhood responsibilities (Fischlmayr & Puchmüller, 2016).

Method

Qualitative investigation, based on the experience of the subject, as referred by Miles and Huberman (1994), has a huge potential to identify, firstly, the meanings that he attributes to the events, processes and structures of his life and, secondly, the association of that meanings to his social context. Therefore, we opted for an exploratory research: an embedded case study (Yin, 2011). Our context of analysis was a multinational company of the automotive sector specialized in electric components and our case of study concerns the IBTs. The units of the analysis were the participants that constitute our sample.

The reason we chose this multinational as the context of analysis was its strong international activity: it currently counts with approximately 135 IBTs residing in Portugal. At this company, business travels are defined as movements for successive days that require the departure of the employee from Portugal to another country and that does not exceed a three-month period. According the internal guidelines of the company, all travels must be planned with 15 days in advance and all the expenses are covered by the employer. In this multinational, all IBTs belong to transnational teams, distributed worldwide, and report to one of the company three central offices, located in Europe, North America and Asia.

Participants

Our sample was selected by the Human Resources (HR) through three criteria: (a) being Portuguese; (b) performs a minimum of 12 business travels per year; and (c) the destiny of the travels varies between two or more countries. We had 12 IBT's whose characteristics (gender and family unit) are representative of this population in our context of study. We consider 11 IBTs for analysis, excluding the one that was aim for the exploratory interview. To assure the confidentiality and the anonymity, guaranteed in advance to the participants, we opted for a description segmented by categories, namely: biographical and professional data and the characterization of the business travels.

The age of participants varies between 29 and 50 years old (M = 39.45; SD = 6.56; Md = 40), being that 73% is men and 27% is women; 55% of the subjects is married, 27% is single, 9% is common law married, and 9% is divorced; and, still, 55% has at last a minor under his responsibility. Their areas of study are, predominantly, Engineering and Applied Computer Science and are assigned to jobs in manufacturing and/or strategy. Referring to the seniority in the organization (M = 14.45; SD = 10.30; Md = 12) and as an IBT (M = 11.55; SD = 7.63; Md = 12) it varies between two and 29 years. The goals of the travels differ considering the job and the actuation area of the participant, varying between: visits to the client factories for inspections and recoveries; visits to factories belonging to the organization to support their activity; and, finally, in the case of participants with strategic jobs, visits to central structures. The medium frequency of the travels is two times a month, and the medium duration is five days. Between 2015 and 2016, all the participants travelled to Europe; 82% travelled, also, to North Africa; 18% to Asia and 9 % to North America.

Data collection procedures and ethical considerations

Per Yin (2009), a case study shall contain data triangulation. Therefore, we selected two methods of data collection: document analysis and semi-structured interviews. The document analysis presents several characteristics that make this method effective: it refers to several periods of time, events and locations, and can be used to both clarify terms said in the interviews and to corroborate the information that comes from other data sources (Yin, 2009). Therefore, first we consulted several documents related to the norms that define how the international mobility of employees happens in that specific context, and the job descriptions of the several participants, allowing us to better apprehend their functional context. We also held a meeting with the HR and visited the organizational context.

Regarding the semi-structured interview, it is a technique frequently used in the qualitative research because is expected that the subjects are more susceptible to share their point of view in a flexible context (Flick, 1998). Prior to the interviews, we performed an exploratory interview and the resulting data gave rise to a semi-structured guide: (a) biographic data; (b) professional situation; (c) characteristics of the travels; and (d) perception and sources of stress related to the travels. Our guide, similarly to the DeFrank et al. (2000) study, was structured in accordance with the travel stages allowing us to access the particularities of each phase, namely: the moderators of the travel stress; the professional and personal consequences of the travels, and cross-travel issues - the projection of the professional future and the evolution of the occupational stress experience throughout the professional career. The last one refers to the transactional construct of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987).

We started by holding a meeting with HR to better understand the context in structural, functional and cultural terms; we visited the office and the production area; and consulted several institutional documents. Concluded this phase, we conducted an unstructured interview with an IBT from the same context. The data gave rise to a semi-structured guide, tested later in a pilot interview and analyzed with the QSR International's NVivo 11 Software. After this analyze, we conducted the remaining interviews using the same script - now validated - until we reached the theoretical saturation (Bachiochi & Weiner, 2004). The interviews took place during working hours and at the workplace of the employee, with HR authorization. The audio was fully registered and the average length of the interviews was of 60'32''.

Data analysis procedures

We chose the content analysis, defined by Bardin (1977), as a set of communication analysis techniques that use systematic and objective procedures to describe the message's content. We started by transcribing the interviews, proceeding to its analysis using QSR International's NVivo 11 Software. In order to minimize the data collected, the information was categorized according to the semantic criteria using a code system (Bardin, 1977). After the categorization, it was asked to an external researcher to codify 10% of the text corpus, obtaining 96% of concordance which indicates a good consistency of the code system and the codification (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Results and Discussion

Sources of occupational stress

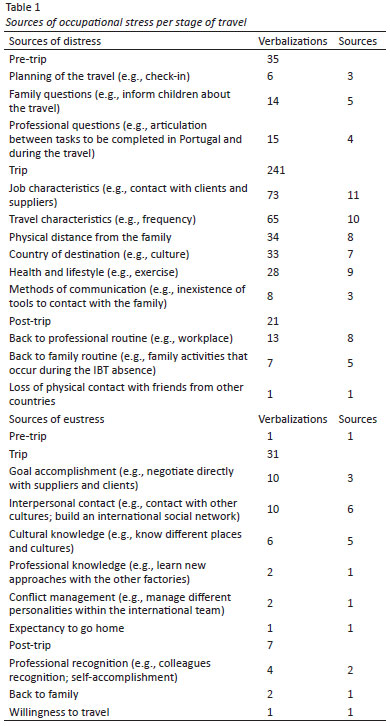

Our study identifies sources of distress and eustress from the various stages of travel - pre-trip, trip and post-trip - which indicates us that each stage encompasses specific aspects capable of induce stress in the traveller. Table 1 displays more information concerning the identified sources.

As seen on Table 1, distress was predominant (88%) when comparing to eustress, which corroborates the necessity to explore the demands of the travels to the employees. Secondly, we identify specific sources of eustress that could help to increase traveller's well-being.

Regarding the sources of distress, sources of the trip stage were prevalent (81%). In a study with executive IBTs, DeFrank et al. (2000) found that, although there are several sources of stress in the stages that precedes and proceeds the travel, it is far more frequent the occurrence of stress in the trip stage.

In the trip stage, we identified more specific sources of stress, underlining the job characteristics - "It is not the travels for themselves that provoke the stress, it is the job that is inherent, it is the inherent stress of dealing with the problems" (P1) - and the travel characteristics - "When it is more frequent it is more stressful, given the fact that we are always travelling to go a place, come back for the weekend, go to another place next week, come back. It becomes tiring" (P2). Both categories refer to professional aspects that can be modified to reduce the sources of distress to which travellers are exposed.

We also identified other sources of distress, presented in Table 1. The family is presented in every stage of the travel as a source of distress, and it seems to be a bidirectional relation: the separation of the family is a source of distress to the traveller and for his family -"The most difficult part is with my son; I must explain to him that I am going to travel for several days. Now he is bigger, it is worse. It is harder for him to accept that I am going out for several days" (P11). Mayerhofer et al. (2004) indicated that the distance from the family has effects on every single member of the family and that it is frequent for the IBTs to feel worried about the consequences of their absence, especially for their children.

Referring to the eustress sources we detected that it is more frequent the occurrence of eustress on the trip stage too (80%), with emphasis on the interpersonal contact and the accomplishment of goals - "On a personal level I feel a positive pressure to accomplish the goals in that space of time and that, for me, is positive because it really makes me work harder to accomplish all the goals" (P2). Per Westman and Etzion (2002), this last source induces positive emotions. We verified that even if the complexity of the tasks constitutes a source of distress, the accomplishment of the goals is gratifying to the travellers.

Managing the occupational stress

In our study, coping was predominant (99%) when comparing with savoring. This was expected, regarding the number of sources of distress identified. According to Folkman and Moskowitz (2000), the strategies of coping are not meant just to reduce distress, although their goal is to reduce discomfort in the face of an adverse situation by promoting the individual's adaptation (Antoniazzi, Dell'Aglio, & Bandeira, 1998). In the same way, the strategies of savoring identified seems to constitute an extension of the eustress sources.

Regarding the coping strategies, we identified strategies focused on emotions and on problems, verifying a predominance of this last (73%). The application of this type of strategies indicates that our IBTs feel that they can do something constructive facing the distress sources (Ribeiro & Rodrigues, 2004): "Before the trips I try to dispatch everything that I have pending to be as comfortable as possible during the trip" (P3).

Moderators of the occupational stress

Our research identified more factors viewed as moderators that those presented in the HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007). We verify a predominance of the professional factors (46%), followed by the personal moderators (24%), which include the individual characteristics referred in the HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007), and the family factors (19%).

Firstly, the prominent professional factors were the travel characteristics (e.g., duration, frequency), the job characteristics (e.g., goals of the travels, salary), and the organizational support. The IBTs spend a lot of hours travelling and working out of the comfort zone of the organization, so that per Welch et al. (2007), the organizational support is essential to make them feel safe, especially when facing unforeseen events during the travel.

Secondly, referring to the personal moderators, the travellers emphasize several individual characteristics: have a good capacity of adaptation, be a good communicator and enjoy the interpersonal contact, manage the conflicts easily, have a good capacity of negotiation, act calmly, be patient, mature and assertive, be an active and healthy person, be willing to learn, enjoy travelling and, at last, have the technical know-how regarding the purpose of the travels.

DeFrank et al. (2000) claims that the personality can influence the type and severity of the experienced stress during the travels. A deep knowledge about these characteristics can also allows the elaboration of a traveller's profile that helps organizations to improve the functional descriptions of those whose activity includes international mobility. These functional descriptions shall be the base of all HR-related processes.

Thirdly, we verify that the family is not only a source of distress and eustress but also a moderator, as the household assumes different roles according to the context. Aspects like the marital status, and the family unit and support are important moderators. Therefore, we calculated the distribution of the distress sources by employees with children and without children and we observed that 55% of the distress verbalizations were prevenient of travellers with children. Regarding to the marital status we verify that 82% of the distress verbalizations were from married employees or in common law marriage.

At last, we identify another two factors that seems to moderate the perceived stress, specifically: the accessibility of the technologies of information and communication that allow the traveller to talk with his family, and the characteristics of the country of destination (e.g., language, time zone, security, culture and food habits).

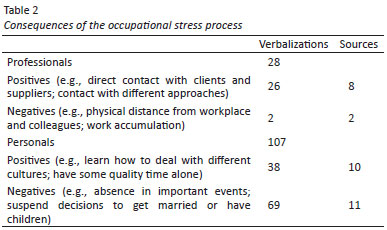

Consequences of the occupational stress process

In our study, we verify that the consequences of the travels are mostly personal and negative. The travels seem to accomplish their professional purpose, adding value to the IBT career and to the organization, but with prejudice to the personal dimension of the traveller, alerting the companies for the necessity to respect the personal and family dimensions in their international mobility policies (DeFrank et al., 2000). For more information, see Table 2.

At the personal level, Gustafson (2014) emphasizes the negative impact of the travels on the IBT family. Even though in this type of international mobility is not necessary the dislocation of the family - which avoids issues related to their relocation (Shaffer et al., 2012) -the travel has consequences to the traveller and his family: IBTs with family feel, recurrently, that the travel affects the family routine considering that in some important moments they are far from home. The travel implies planning, preparation and coordination at home, and sometimes negotiation with the spouse (Gustafson, 2014). A study developed with Portuguese IBTs indicates that's although the IBT has some control upon the work-family balance, the companies are determinants in the maintenance of this balance (Pinto & Maia, 2015).

Experience of occupational stress throughout the professional career

Finally, it would be expected that occupational stress decreases with professional experience, given that through the years IBTs acquire strategies to manage the common sources of stress (e.g., planning of the travel, culture of destination, return to family and professional routines). Nevertheless, we verify that although there's a stage of adaptation to the travels and, consequently, a decrease of the perceived stress, as the years pass by the travel is no longer a novelty, becoming only a professional obligation with costs at the physical and psychological health of the professional (DeFrank et al., 2000) and his family (Baker & Ciuk, 2015):

When I started it would be an adventure, I was just out of the college, with no personal commitments at the family level, I was not married, I had no children, so for me turned out to be an interesting adventure. Discover and learn as well. Today this phase is past, I am in a phase of commitment and professional responsibility (P11, IBT for more than ten years).

To complement the information here presented we calculated the distribution of the distress sources by employees that travel for a period of 10 years or less and employees who have been traveling for more than 10 years, verifying that 57% of the distress verbalizations were made by senior employees. This makes us conclude that, in fact, considering our participants, stress increases during the IBT career.

In this study we adopted the HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007), a model that implies a large number of dimensions. This allowed us to collect a huge variety of information about the occupational stress in this population without neglecting the complexity of business travels. This is a cross-sectional study; nevertheless, the HMS ( Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007) enabled us to observe how the occupational stress process happens during the travels and over time.

We conclude, firstly, that the travels are a source of distress, which confirms the need to explore the impact of the travel and its challenges to the physical and psychological health of the traveller. The several stages of the travel, especially the travel itself, encompasses professional and extra-professional factors inductors of distress.

On one hand, the sources of distress identified suggest the active role that the companies must have in the maintenance of international mobility policies accurate to this type of mobility and considering the travel stage (DeFrank et al., 2000); one the other hand, the family sources of distress emphasize the need of negotiation and adaptation of the family to the reality of the IBT (Gustafson, 2014; Nicholas & McDowall, 2012). As Jensen (2014) considered, decreasing emotional exhaustion implies more than simply reducing the number of travels. The companies need to be committed with this purpose and give the employees the opportunity to control their own travel schedule.

Secondly, we verify that travelling contains mostly personal consequences of negative matter, especially to the family. We conclude that IBTs tend to opt for coping strategies focused on the problem instead of focusing on the emotions to deal with the stressors, presenting a constructive and active attitude towards them (Ribeiro & Rodrigues, 2004).

At last, regarding the moderators, we identified more factors than those considered in the HMS (Nelson & Simmons, 2003a; Nelson & Simmons, 2011; Simmons & Nelson, 2007), specifically professional, personal and family factors, concluding that for the traveller it is important to feel supported both by colleagues and by their family. Nevertheless, it is relevant to reflect about the personal moderators identified, since the several verbalizations highlight characteristics that are recognized by all the IBTs as factors to the success of the mobility and that act as a context filter, influencing the perception of context. DeFrank et al. (2000) studied the individual characteristics deliberating that a deep knowledge about those traits can help companies in definining an accurate profile of IBTs. The addition of behavioral skills, required by a traveler, in a job description shall facilitate the implementation of several HR related processes (Dessler, 2013), including the recruitment and selection of the global travellers (Phillips, Gully, Mccarthy, Castellano, & Kim, 2014). Thus, this will impact on the traveller's well-being and on the achievement of the travel goals, especially long-term.

Further investigation

Per Bryman (2000), although the results of the case studies are not generalizable, these still make possible the establishment of patterns and relations with theoretical relevance and, subsequently, are important for the development of theories. For the company where this study took place, the identification of stressors and moderators of stress shall help in improving the interventions at several levels (e.g., recruitment and selection; training and development) and in designing stress prevention strategies for its IBTs that allow them to recognize and control occupational stress.

Considering the exploratory nature of this study, the aspects covered in it and its conclusions, we put forward the following ideas: the study of IBTs from other professional contexts in order to explore the similarities and differences between them based in the HMS; the design of an IBT profile using personality tests; the deepening of the coping and savoring strategies in order to evaluate their short-term and long-term effectiveness; and, at last, the study of the relation between the distress level and the moderators.

References

Antoniazzi, A. S., Dell'Aglio, D. D., & Bandeira, D. R. (1998). O conceito de coping: Uma revisão téorica. Estudos de Psicologia, 3(2),273-294. [ Links ]

Bachiochi, P. D., & Weiner, S. P. (2004). Qualitative data collection and analysis. In S. G. Rogelberg (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 161-183). London: Blackwell Publishing. doi: 10.1111/b.9781405127004.2004 [ Links ]

Baker, C., & Ciuk, S. (2015). "Keeping the family side ticking along": An exploratory study of the work-family interface in the experiences of rotational assignees and frequent business travellers. Journal of Global Mobility, 3(2),137-154. doi: 10.1108/JGM-06-2014-0027 [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (1977). Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ] Beehr, T. A. (1995). Psychological Stress in the workplace. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brookfield Global Relocation Services. (2016). Breakthrough to the future of global talent mobility: 2016 Global Mobility Trends Survey. Illinois: Brookfield Global Relocation Services. [ Links ]

Bryant, F. B., Chadwick, E. D., & Kluwe, K. (2011). Understanding the processes that regulate positive emotional experience: Unsolved problems and future directions for theory and research on savoring. International Journal of Wellbeing, 1(1),107-126. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v1i1.18 [ Links ]

Bryman, A. (2000). Research methods and organization studies. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Collings, D. G., Scullion, H., & Morley, M. J. (2007). Changing patterns of global staffing in the multinational enterprise: Challenges to the conventional expatriate assignment and emerging alternatives. Journal of World Business, 42(2),198-213. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2007.02.005 [ Links ]

Cooper, C. L., Dewe, P. J., & O'Driscoll, M. P. (2001). Organizational stress: A review and critique of theory, research, and applications. Foundations for organizational science. London: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Cunha, M. P., Rego, A., Cunha, R. C., & Cabral-Cardoso, C. (2007). Manual de comportamento organizacional e gestão (7º Edição). Lisboa: Editora RH. [ Links ]

Cunha, M. P., Rego, A., Cunha, R. C., Cabral-Cardoso, C., & Neves, P. (2016). Manual de comportamento organizacional e gestão (8ª Edição). Lisboa: Editora RH. [ Links ]

De Cieri, H., Fenwick, M., & Hutchings, K. (2005). The challenge of international human resource management: Balancing the duality of strategy and practice. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(4),584-598. doi: 10.1080/09585190500051688 [ Links ]

DeFrank, R. S., Konopaske, R., & Ivancevich, J. M. (2000). Executive travel stress: Perils of the road warrior. Academy of Management Perspectives, 14(2),58-71. doi: 10.5465/AME.2000.3819306 [ Links ]

Dessler, G. (2013). Human resource management (13th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson. [ Links ]

Dewe, P. J., O' Driscoll, M. P., & Cooper, C. L. (2012). Theories of psychological stress at work. In Robert J. Gatchel & Izabela Z. Schultz (Eds.), Handbook of Occupational health and wellness. Handbooks in health, work, and disability (pp. 23-38). New York: Springer Science+Business Media. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4839-6_2 [ Links ]

Dobrai, K., Farkas, F., Karoliny, Z., & Poór, J. (2012). Knowledge transfer in multinational companies -Evidence from Hungary. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica, 9(3),149-161. [ Links ]

Erez, M., Lisak, A., Harush, R., Glikson, E., Nouri, R., & Shokef, E. (2013). Going global: Developing management students'cultural intelligence and global identity in culturally diverse virtual teams. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 12(3),330-355. doi: 10.5465/amle.2012.0200 [ Links ]

Ernst & Young (2012). Frequent business traveller survey report. London: EY. [ Links ]

Fischlmayr, I. C., & Puchmüller, K. M. (2016). Married, mom and manager -How can this be combined with an international career? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(7),744-765. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2015.1111250 [ Links ]

Flick, U. (1998). An introduction to qualitative research. London: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. The American Psychologist, 55(6),647-654. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.647 [ Links ]

Frese, M., & Sonnentag, S. (2005). Stress. In N. Nicholson, P. G. Audia & M. M. Pillutla, (Eds.), Blackwell encyclopedic dictionary of organizational behavior (pp. 378-380). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing/Books. [ Links ]

Gustafson, P. (2014). Business travel from the traveller's perspective: Stress, stimulation and mormalization. Mobilities, 9(1),63-83. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2013.784539 [ Links ]

Hart, P. M., & Cooper, C. L. (2001). Occupational stress: toward a more integrated framework. In N. Anderson, D. S. Ones, S. H. Kepir, & C. Viswesvaran (Eds.), Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 93-114). SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Ivancevich, J. M., Konopaske, R., & DeFrank, R. S., (2003). Business travel stress: A model, propositions and managerial implications. Work & Stress, 17(2),138-157. doi: 10.1080/0267837031000153572 [ Links ]

Jensen, M. T. (2014). Exploring business travel with work-family conflict and the emotional exhaustion component of burnout as outcome variables: The job demands-resources perspective. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(4),497-510. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.787183 [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of personality, 1(3),141-169. [ Links ]

Mäkelä, L., Bergbom, B., Saarenpää, K., & Suutari, V. (2015). Work-family conflict faced by international business travellers: Do gender and parental status make a difference? Journal of Global Mobility, 3(2),155-168. doi: 10.1108/JGM-07-2014-0030 [ Links ]

Mäkelä, L., Saarenpää, K., & McNulty, Y. (2017). International business travelers, short-term assignees and international commuters. In Y. McNulty & J. Selmer (Eds.), Research handbook of expatriates (pp. 276-294). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Mayerhofer, H., Hartmann, L. C., & Herbert, A. (2004). Career management issues for flexpatriate international staff. Thunderbird International Business Review, 46(6),647-666. doi: 10.1002/tie.20029 [ Links ]

Mayerhofer, H., Hartmann, L. C., Michelitsch-Riedl, G., & Kollinger, I. (2004). Flexpatriate assignments: a neglected issue in global staffing. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(8),1371-1389. doi: 10.1080/0958519042000257986 [ Links ]

Meyskens, M., Von Glinow, M. A., Werther, Jr, W. B., & Clarke, L. (2009). The paradox of international talent: Alternative forms of international assignments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(6),1439-1450. doi: 10.1080/09585190902909988 [ Links ]

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. London: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Nelson, D. L., & Simmons, B. L. (2003a). Health psychology and work stress: A more positive approach. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 97-119). Washington: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/10474-005 [ Links ]

Nelson, D. L., & Simmons, B. L. (2003b). Eustress: An elusive construct, an engaging pursuit. In P. L. Perrewe & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Emotional and physiological processes and positive intervention strategies (research in occupational stress and well-being, volume 3) (pp. 265-322). United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. doi: 10.1016/S1479-3555(03)03007-5 [ Links ]

Nelson D. L., & Simmons B. L. (2011). Savoring eustress while coping with distress: The holistic model of stress. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 55-74). Washington: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1007/s10926-011-9328-y [ Links ]

Newton, C., & Teo, S. (2014). Identification and occupational stress: a stress-buffering perspective. Human Resource Management, 53(1),89-113. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21598 [ Links ]

Nicholas, H., & McDowall, A. (2012). When work keeps us apart: A thematic analysis of the experience of business travellers. Community, Work & Family, 15(3),335-355. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2012.668346 [ Links ]

Phillips, J. M., Gully, S. M., Mccarthy, J. E., Castellano, W. G., & Kim, M. S. (2014). Recruiting global travelers: The role of global travel recruitment messages and individual differences in perceived fit, attraction, and job pursuit intentions. Personnel Psychology, 67(1),153-201. doi: 10.1111/peps.12043 [ Links ]

Pinto, L. H., Cabral-Cardoso, C., & Werther, W. B. (2012). Adjustment elusiveness: An empirical investigation of the effects of cross-cultural adjustment on general assignment satisfaction and withdrawal intentions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36,188-199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.06.002 [ Links ]

Pinto, L. H., & Maia, H. S. (2015). Work-life interface of Portuguese international business travelers. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 28(2),195-212. doi: 10.1108/ARLA-05-2014-0066 [ Links ]

PORDATA. (2016, May). Viagens: Total, por destino e motivo principal -Portugal. Retrieved from http://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Viagens+total++por+destino+e+motivo+principal+-2549 [ Links ]

Quick, J., & Henderson, D. (2016). Occupational stress: Preventing Suffering, enhancing wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(5),459. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13050459 [ Links ]

Ramos, M. (2001). Desafiar o desafio: Prevenção do stress no trabalho. Lisboa: Editora RH. [ Links ]

Ramsey, J. R., Leonel, J. N., Gomes, G. Z., & Monteiro, P. R. R. (2011). Cultural intelligence's influence on international business travelers' stress. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 18(1),21-37. doi: 10.1108/13527601111104278 [ Links ]

Ribeiro, J. L., & Rodrigues, A. P. (2004). Questões acerca do coping: A propósito do estudo de adaptação do Brief Cope. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 5(1),3-15. [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Coping with job stress. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Vol. 4, pp. 902-904). Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Selye, H. (1976). Forty years of stress research: Principal remaining problems and misconceptions. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 115(1),53-56. [ Links ]

Shaffer, M. A., Kraimer, M. L., Chen, Y. P., & Bolino, M. C. (2012). Choices, challenges, and career consequences of global work experiences: A review and future agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4),1282-1327. doi: 10.1177/0149206312441834 [ Links ]

Simmons, B. L., & Nelson, D. L. (2001). Eustress at work: The relationship between hope and health in hospital nurses. Health Care Management Review, 26(4),7-18. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200110000-00002 [ Links ]

Simmons, B., & Nelson, D. (2007). Eustress at work: Extending the holistic stress model. In D. L. Nelson & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Positive organizational behavior (pp. 40-54). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781446212752.n4 [ Links ]

Thomas, D. C., & Lazarova, M. B. (2006). Expatriate adjustment and performance: A critical review. In G. K. Stahl & I. Björkman (Eds.), Handbook of research in international human resource management (pp. 247-264). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. doi: 10.4337/9781845428235 [ Links ]

Welch, D. E., Welch, L. S., & Worm, V. (2007). The international business traveller: A neglected but strategic human resource. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(2),173-183. doi: 10.1080/09585190601102299 [ Links ]

Westman, M., & Etzion, D. (2002). The impact of short overseas business trips on job stress and burnout. Applied Psychology, 51(4),582-592. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00109 [ Links ]

Westman, M., Etzion, D., & Chen, S. (2009). Crossover of positive experiences from business travelers to their spouses. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(3),269-284. doi: 10.1108/02683940910939340 [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. London: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ] Yin, R. K. (2011). Applications of case study research. London: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Ana Rita Cardoso

Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação da Universidade do Porto, A/C Filomena Jordão

Rua Alfredo Allen

4200-135 Porto, Portugal

E-mail: aritacardoso@outlook.com

Recebido em: 30/05/2017

Primeira decisão editorial em: 04/07/2017

Versão final em: 02/08/2017

Aceito em: 23/09/2017