Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia Clínica

versão impressa ISSN 0103-5665versão On-line ISSN 1980-5438

Psicol. clin. vol.33 no.2 Rio de Janeiro maio/ago. 2021

https://doi.org/10.33208/PC1980-5438v0033n02A09

FREE SECTION

Depressive symptoms associated with the expectation of social support in the elderly: Data from the FIBRA-RJ study

Sintomas depressivos associados à expectativa de apoio social em idosos: Dados do estudo FIBRA-RJ

Síntomas depresivos asociados con la expectativa de apoyo social en los ancianos: Datos del estudio FIBRA-RJ

Pricila Cristina Correa RibeiroI; Felipe Cordeiro AlvesII; Roberto Alves LourençoIII

IDoutora em Saúde Coletiva. Professora Adjunta do Departamento de Psicologia, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. pricilaribeiro@ufmg.br

IIPsicólogo. Mestrando em Psicologia pela Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. felipepsi@live.com

IIIDoutor em Saúde Coletiva. Professor Titular do Departamento de Medicina Interna da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas e Coordenador do Laboratório de Pesquisa em Envelhecimento Humano (GeronLab) da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. roberto.lourenco@globo.com

ABSTRACT

The progressive aging of the population and the social transformations resulting from this phenomenon have fostered studies that include social support as a relevant variable for understanding the determinants of mental health in old age. This study evaluated the association between the expectancy of social support and clinically significant depressive symptoms (CSDS) in community-dwelling older adults, controlling the clinical and sociodemographic variables involved in this interaction. A cross-sectional study using the database of the FIBRA-RJ Study that includes elderly (over 65 years old) clients of a private health care plan who resided in northern districts of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro. Of the 776 participants, 66% were women; the mean age was 76.8 (σ=6.77) years, and the mean schooling was 10 (σ=5.077) years of studies. The prevalence of CSDS was 22%. People who expect assistance in the case of functional dependency showed lower rates of prevalence of CSDS than the group without such expectation (OR=1.976). The expectation of receiving support only from the formal caregiver was associated with CSDS (p<0.001). The findings reinforce the importance of psychosocial variables as a factor associated with mood disorders in the elderly.

Keywords: depression; social support; aging.

RESUMO

O envelhecimento progressivo da população e as transformações sociais decorrentes desse fenômeno fomentam estudos que incluem o apoio social como uma variável relevante para a compreensão dos determinantes da saúde mental na velhice. Este estudo avaliou a associação entre a expectativa de apoio social e os sintomas depressivos clinicamente significativos (CSDS) em idosos da comunidade, controlando as variáveis clínicas e sociodemográficas envolvidas nessa interação. Estudo transversal, utilizando dados do Estudo FIBRA-RJ, que incluiu clientes idosos (maiores de 65 anos) de um plano privado de saúde que residiam nos bairros da zona norte do município do Rio de Janeiro. Dos 776 participantes, 66% eram mulheres; a média de idade foi de 76,8 (σ=6,77) anos e a escolaridade média foi de 10 (σ=5,077) anos de estudo. A prevalência de CSDS foi de 22%. As pessoas que acreditavam ter com quem contar no caso de dependência funcional apresentaram menores chances de CSDS em comparação ao grupo que não tinha esta expectativa (OR=1,976). A expectativa de receber apoio apenas do cuidador formal foi associada à CSDS (p<0,001). Os achados reforçam a importância das variáveis psicossociais como fator associado aos transtornos de humor em idosos.

Palavras-chave: depressão; suporte social; envelhecimento.

RESUMEN

El envejecimiento progresivo de la población y las transformaciones sociales resultantes de este fenómeno han fomentado estudios que incluyen el apoyo social como una variable relevante para comprender los determinantes de la salud mental en la vejez. Este estudio evaluó la asociación entre la expectativa de apoyo social y los síntomas depresivos clínicamente significativos (CSDS) en adultos mayores que viven en la comunidad, controlando las variables clínicas y sociodemográficas involucradas en esta interacción. Un estudio transversal, que utiliza la base de datos del Estudio FIBRA-RJ, que incluye clientes de edad avanzada (mayores de 65 años) de un plan privado de atención médica que residían en distritos del norte del municipio de Río de Janeiro. De los 776 participantes, el 66% eran mujeres; la edad promedio fue de 76,8 (σ=6,77) años y la escolaridad promedio fue de 10 (σ=5,077) años de estudios. La prevalencia de CSDS fue del 22%. Las personas que esperan asistencia en el caso de dependencia funcional tienen tasas más bajas de presentar CSDS en comparación con el grupo que no tiene esta expectativa (OR=1,976). La expectativa de recibir apoyo solo del cuidador formal se asoció con CSDS (p<0,001). Los hallazgos refuerzan la importancia de las variables psicosociales como un factor asociado con los trastornos del estado de ánimo en los ancianos.

Palabras clave: depresión; apoyo social; envejecimiento.

Introduction

Depression is one of the most frequent mental disorders in the elderly population (Santos et al., 2015; Polyakova et al., 2014). It negatively impacts the tools that the elderly possess to respond and adapt to pathologies and functional declines present in this stage of life. Its incidence is associated with increased costs in health services (Aziz & Steffens, 2013), worse outcomes of pathological evolutions and increased risk of death (Eurelings et al., 2018).

To investigate depression in the elderly population, it is necessary to consider depressive symptoms, regardless of a diagnosis of major depression. The term Clinically Significant Depressive Symptoms (CSDS) refers to the presence of mood-altering symptoms that may characterize a clear picture of depression (diagnosable) or subsyndromal depression (Sousa-Muñoz et al., 2013). According to a study by Ramos et al. (2015), the prevalence of depression in the elderly population ranged from 3% to 15% and CSDS from 13% to 39%. These authors pointed out that, among the elderly, for outcomes such as cumulative morbidity, CSDS are more significant indicators than depressive syndromes.

Several psychosocial factors have been studied in an attempt to broaden the understanding of the risks and protection of mental health in old age (Weissman & Russel, 2018; Kim et al., 2018). Among these factors, we highlight the social support construct (SS) that emerged in areas related to psychology since the 1970s. In the studies of Cobb (1976), its first formulation included the individual's beliefs about being loved, appreciated, and an object of concern by loved ones (Cardoso & Baptista, 2015). Social support is currently defined as the product of social interaction acts and classified from emotional, material, and informational dimensions (Neri & Vieira, 2013).

According to Maia et al. (2016), the relevance of one's network and social support increases in the course of aging due to increased chances of disease and functional dependence. Thus, the progressively aging population and the social transformations resulting from this phenomenon have fostered perspectives that include social support as a relevant variable in health care for the elderly (Harada et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2016). The present study investigated the association between clinically significant depressive symptoms and the expectation of social support in the elderly, controlling for the clinical and psychosocial variables that may modify this relationship.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study that used data from the Frailty in Elderly Brazilians Study - Rio de Janeiro section (FIBRA-RJ), performed between 2009 and 2011, by the Research Laboratory on Human Aging (GeronLab) of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the State University of Rio de Janeiro. Fibra-RJ is part of the FIBRA Brasil Network, a multicentric study whose objective was to identify the prevalence and conditions associated with frailty in Brazilian older people, including their relationship with demographic and psychosocial variables (Neri et al., 2013). The network was organized in different poles of research linked to partner institutions, and each pole was selected out of convenience in the cities where the data was collected. FIBRA-RJ interviewed 847 individuals aged 65 and older, clients of a health care provider and who reside in the northern zone of the city of Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, selected by inverse random sampling, stratified by age and sex. For the present study, those who did not answer questions about support expectation and/or the scale for depressive symptoms were not considered. In total, 776 individuals were analyzed.

The participation of the elderly was voluntary, and the rules of the National Commission for Research Ethics of the Ministry of Health (CONEPE) were respected. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, at the State University of Rio de Janeiro. The data collection was carried out in interviews conducted by trained interviewers and performed at the participants' homes. The individuals provided data on their sociodemographic, psychosocial, and health conditions by self-report. The data was obtained following a standardized questionnaire1.

The CSDS were measured using the Geriatric Depression Scale, version 15 (GDS-15) (Almeida & Almeida, 1999) and using the cut-off point 5 (Paradela et al., 2005) to divide the sample into two groups, "without depressive symptoms" and "with depressive symptoms". The cut-off point 5 proposed by Paradela et al. (2005), with a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 71%, is indicated to identify older adults suspected of depression, even in non-specialized contexts. Thus, this instrument was considered useful for evaluating CSDS in the present study, which investigated a community sample of the elderly. The functional capacity for instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with the functional scale of Lawton and Brody (1969) and the ability to perform basic activities of daily living (BADL), measured with the Katz Index (1963), were evaluated. The total sum of the number of BADL and IADL that the respondent did not perform or for which they needed help was used as a continuous variable in the data analysis. Also, the clinical variables of self-perceived health and the number of chronic diseases were analyzed. The self-perceived health was analyzed as dichotomous, and was considered positive when the respondents reported their general health as very good or good, and negative when they evaluated it as regular, poor or very poor. The number of chronic diseases was analyzed with the following categories: no diseases; one disease; two diseases; three or more diseases.

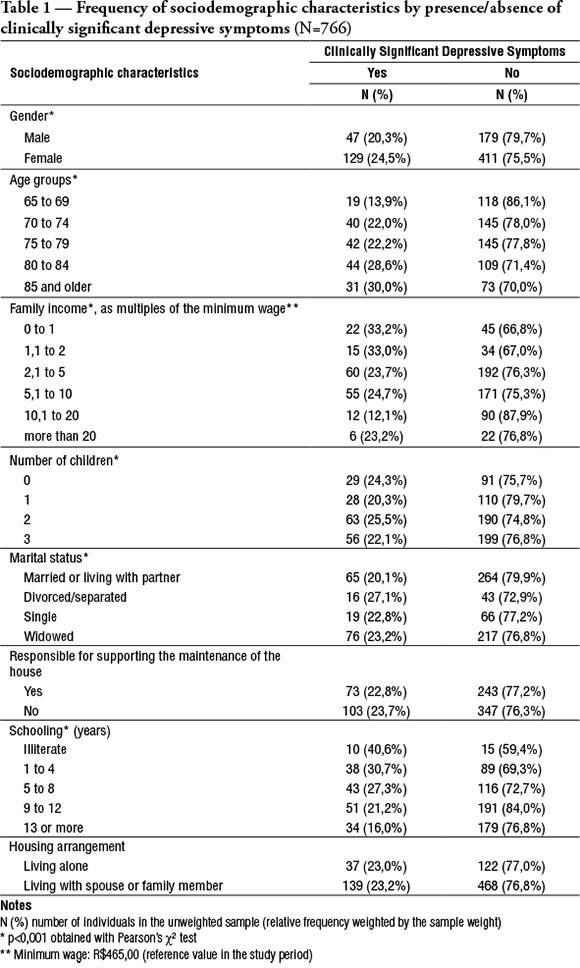

The following sociodemographic and psychosocial variables were acquired by self-report, through a questionnaire structured by the Fibra-RJ interview protocol. From this protocol, the following sociodemographic and psychosocial variables were analyzed: gender, age, income, number of children, marital status, housing arrangement (with whom they were living), responsibility for the maintenance of the house, schooling, satisfaction with the people close to them, and expectation of support. These variables were treated as categorical in the data analysis and their categories are described in Table 1.

The expectation of support was obtained by self-report on whether they could count on someone if help was needed to perform the activities of daily living (ADL) and, if so, who would be that supporting agent. The question about "expectation of support" was applied after the participant answered the FIBRA protocol instruments that assessed the ability for ADL. Thus, it was possible to clarify in the interview that the answer to "expectation of support" referred to support for ADL. To identify the primary support provider, the following predefined categories were presented to the participant: spouse or partner; daughter or daughter-in-law; son or son-in-law; another relative; friend or neighbor; paid professional.

To verify the association between the presence of CSDS and the independent demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables, association analyses were performed with Pearson's χ2 test for the categorical variables, and the Student's t-test, for comparison of the average functional capacity variable that was treated as continuous, with a significance level of 5%. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the odds ratios (and their respective 95% confidence intervals) of the association between CSDS and the independent variables. The analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 18.0. All results of relative frequencies and association measures were analyzed by their sample weight, defined through the sampling process used in the FIBRA-RJ Study.

Results

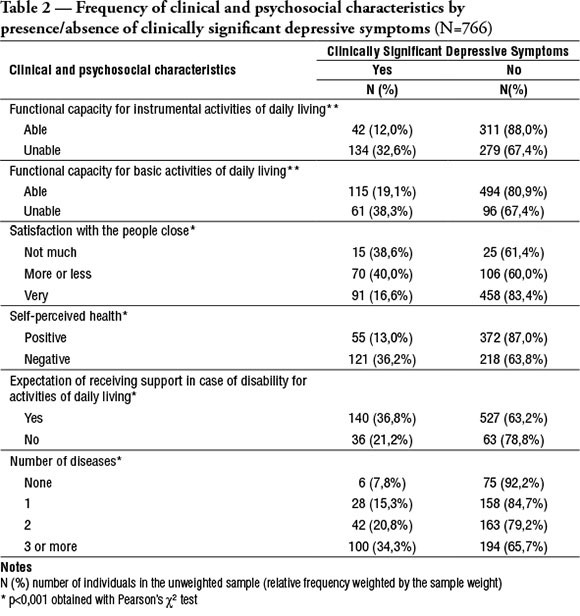

Among the 776 participants, 66% were women; the mean age was 76.8 (σ=6.77) years and the mean schooling was 10 (σ=5.077) years of studies. The prevalence of CSDS was 22%. The mean loss in ADL was 1.19 (σ=1.76) and 3.14 (σ=3.05) activities among the elderly without CSDS and with CSDS, respectively (p<0.001). According to the presence or absence of CSDS, other characteristics of the sample are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Among the sociodemographic variables analyzed, housing arrangement (living alone or living with relatives) and primary responsibility for household support did not present a statistically significant association with the presence of CSDS, with p-values of 0.45 and 0.17, respectively. Therefore, these two variables were excluded from the multiple logistic regression analysis.

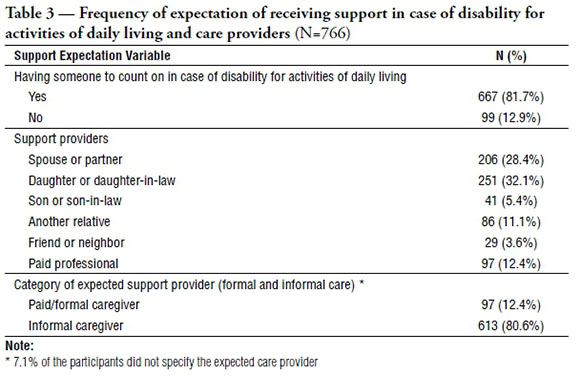

Regarding the expectation of receiving social support, it was observed that 87.1% of the elderly answered that they would have someone to count on in case of disability for ADL, and the expectation of receiving support from informal caregivers was significantly more frequent (80.6%), that is, receiving support from family and friends. Table 3 describes the frequency of this expectation of support and possible providers. It should be noted that there was an association between the presence of CSDS and the expectation of a formal or informal support agent (χ2 (1)=19.68, p<0.001), with a CSDS prevalence of 27.7% among participants who counted on paid professionals to receive support and 22.3% among participants who counted on informal support.

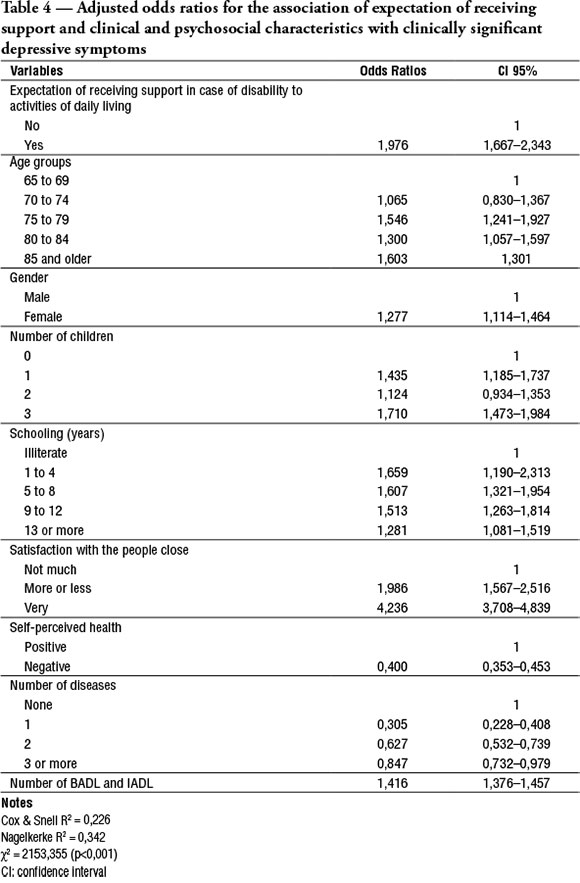

The results of the odds ratios obtained with the multiple logistic regression are described in Table 4. Among the factors associated with CSDS, the increase in age is noteworthy, with the presence of symptoms most frequent among the elderly aged 75 to 79, and 80 years and older compared to the group of younger elderly. It was found that the greater odds of these symptoms for the females were not maintained in the multiple regression model when the variables of clinical and psychosocial conditions were controlled. Regarding the expectation of support, participants who thought they had no one to count on in case of ADL disability were approximately twice as likely (CR=1.976) to present depressive symptoms. The variables of income and of marital status were not maintained in the model since their withdrawal did not alter the explanatory power of the model, although they presented a statistically significant association in the bivariate analyses.

Discussion

This study investigated the perceived social support construct, specifically regarding the expectation of receiving support in case of functional dependence, as a variable associated with the presence of clinically significant depressive symptoms in the elderly. The findings showed a significantly lower chance of finding these symptoms among the elderly with the expectation of receiving social support when compared to those with the expectation of absence of support. Therefore, the hypothesis that the expectation of support appears as a factor associated with depressive symptomatology is confirmed, predominating over other psychosocial conditions, such as the concrete circumstances of housing arrangement. In agreement with these findings, Brazilian (Silva et al., 2016; Rabelo & Neri, 2015) and international (Hu et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2016) studies have established social support as a variable associated with depression in the elderly population. Reviewing the Brazilian production about this issue, Macedo et al. (2018) reaffirmed the expansion of studies in recent years, acknowledging the participation of research on social support (11%) and common mental disorders, among them depression, in Brazil. Among elderly Brazilians, an association of social support, together with the depression variable, with the frailty syndrome was found, confirming the explanatory potential of this variable for depression in the elderly (Souza et al., 2017). However, the relationship between depressive and frailty symptoms is still unclear and challenges researchers and clinicians who seek to understand the relationship and the factors associated with these adversities (Buigues et al., 2015). From the results of this study, it is recommended that more complex models, including factors associated with physical and mental health such as social support, be tested to advance the knowledge about the relationship between these adversities and how to face them in old age.

In the study by Hu et al. (2018), 25 to 28% of the disparities in relation to depressive symptomatology were explained by social support, evaluated as less adequate among elderly living in rural areas, with this association controlled for sociodemographic and clinical variables. Li et al. (2018) found an association between greater social support and greater social participation with the best prognosis of depressive symptomatology.

In this study, satisfaction with the people close to them was another psychosocial variable that presented a negative association with depressive symptoms, which reinforces the importance of self-perception for the elderly regarding their social support and its impact on mental health. Furthermore, it was shown that positive expectations about receiving support in the face of disability were highly prevalent among the elderly, similar to what was found in other Brazilian studies (Guedea et al., 2006; Rodrigues & Neri, 2012). An association between the mode of support expected by the elderly, whether formal or informal, and the depressive symptomatology was also found. These results indicate that older people who do not expect family support were more likely to have depressive symptoms than those who have close relatives to take care of them. The importance of informal and voluntary care, recognized by the elderly while dealing with losses, may indicate that this is a protective factor in relation to depressive symptomatology in old age. In previous studies (Paúl, 2017), it stands out that informal support represents an important indicator of quality of life for the elderly.

There was a predominance of expectation by the elderly of receiving support from the spouse or partner, and from daughters or daughters-in-law. This result may be related to affectivity in these relationships and the provision of support in previous situations by these loved ones (Silva & Rabelo, 2017). The expectation of support provided by a female relative, other than a spouse, maybe the result of the socially-shared assumption about the role of women as caregivers (Isaac et al., 2018).

As for other factors associated with depressive symptoms, the findings in which the presence of depressive symptoms was associated with advanced age (Sengupta and Benjamin, 2015; Ventura et al., 2016), low schooling (Mendes-Chiloff et al., 2019; Lima et al., 2016), the greater number of diseases (Nascimento et al., 2016; Amaral et al., 2018), and the presence of disability (Mendes-Chiloff et al., 2019; Nóbrega et al., 2015) were corroborated. However, contrary to other findings (Gero et al., 2017; He et al., 2016; Ventura et al., 2016), in this study, the variables of income, marital status, and living alone had no influence on the explanatory power of the multi-factor model associated with depressive symptoms.

It has been discussed in the literature that the effects of housing arrangement variables - used as a proxy for social vulnerability - on depression in the elderly should be reviewed, as they may not capture the level of social interaction. Older adults living alone can have a diverse social network and even better well-being than older adults who live with other people (Djundeva et al., 2019). In addition, the mediating factors should be further studied. For example, the effect of gender differences and the level of social cohesion in the neighborhood can mitigate the effect of home arrangement (Honjo et al., 2018), and the level of reciprocity can mediate the association between income level and depressive symptoms (Han et al., 2018).

Another controversy was with the literature pointing to a greater presence of depressive symptoms among women (Defrancesco et al., 2018; Laborde-Lahoz et al., 2015). It was verified that the association of these depressive symptoms with women occurred only in the bivariate analyzes, that is, when the other sociodemographic and clinical variables were not considered, which may indicate that other factors that lead to physical and psychosocial changes represent the main determinants of depression among the elderly. Loss of ability to perform daily tasks independently is recognized as a risk factor for depressive symptoms in the elderly (Heser et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2016), as well as an increase in the number of diseases (Nascimento et al., 2016; Amaral et al., 2018). Women, due to their greater longevity, are more likely to be affected by functional declines and comorbidities associated with depression. Thus, the contradiction with the results of other studies (such as Defrancesco et al., 2018; Laborde-Lahoz et al., 2015; Lampert & Ferreira, 2018) may be due to the fact that physical determinants, such as capacity losses, have not been controlled in these studies. In this sense, we can also justify the contradictions in relation to the literature for the variables living alone, income, and marital status.

Population-based studies on depression, its prevalence and associated aspects are still scarce in Brazil (Ramos et al., 2015). Thus, this study sought to further knowledge about the aspects associated with the mental health of the elderly population. By focusing on a sample of older adults served by a private health care plan, the sociodemographic profile of the sample in this study differs from the elderly population in general and from older adults who rely solely on coverage by the public health care system, presenting, for example, higher levels of income and schooling (Malta et al., 2011). Hence, it is necessary to reproduce studies of this type in different population scenarios in order to understand how sociocultural conditions can impact mental health outcomes of the older demographic.

In order to confirm and amplify the inferences gathered from the cross-sectional design, it is suggested that future studies investigate the effect of the expectation of social support on changes of physical and mental health experienced during aging. In addition, we recommend the expansion of ways to measure social support that in this investigation were limited to the expectation of support. Nevertheless, it is recognized that the findings obtained reinforce the importance of psychosocial variables as a factor associated with mood disorders in the elderly, allowing us to conclude that these indicators, which are generally quick and inexpensive to obtain, should be included among the measures for identifying risk groups in the elderly. Thus, mental health efforts must also focus on the specificities of aging, including the expectation of support in the face of the loss of functional capacity, as a way of identifying and assisting the elderly at greater risk of depression. The present study also leads to reflection on the need to structure public policies aimed at supporting informal care for the elderly, such as the provision of technical assistance to family caregivers, and the need to expand community and institutional networks of social and emotional support to the elderly, as these represent care alternatives for the elderly who cannot count on family members and would demand even more support from public policies to mitigate losses in old age.

References

Almeida, O. P.; Almeida, S. A. (1999). Short versions of the geriatric depression scale: A study of their validity for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 858-865. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199910)14:10<858::AID-GPS35>3.0.CO;2-8 [ Links ]

Amaral, T. L. M.; Amaral, C. D. A.; Lima, N. S. D.; Herculano, P. V.; Prado, P. R. D.; Monteiro, G. T. R. (2018). Multimorbidity, depression, and quality of life among older adults assisted in the Family Health Strategy in Senador Guiomard, Acre, Brazil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 23(9), 3077-3084. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018239.22532016 [ Links ]

Aziz, R.; Steffens, D. C. (2013). What are the causes of late-life depression? The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 36(4), 497-516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2013.08.001 [ Links ]

Buigues, C.; Padilla-Sánchez, C.; Garrido, J. F.; Navarro-Martínez, R.; Ruiz-Ros, V.; Cauli, O. (2015). The relationship between depression and frailty syndrome: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 19(9), 762-772. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.967174 [ Links ]

Cardoso, H. F.; Baptista, M. N. (2015). Evidence regarding the validity of the scale of perceived social support (adult version): A correlational study. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 35(3), 946-958. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703001352013 [ Links ]

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatics, 38(5), 300-314. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003 [ Links ]

Defrancesco, M.; Pechlaner, R.; Kiechl, S.; Willeit, J.; Deisenhammer, E. A.; Hinterhuber, H.; Rungger, G.; Gasperi, A.; Marksteiner, J. (2018). What characterizes depression in old age? Results from the Bruneck study. Pharmacopsychiatry, 51(04), 153-160. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-119417 [ Links ]

Djundeva, M.; Dykstra, P. A.; Fokkema, T. (2019). Is living alone "aging alone"? Solitary living, network types, and well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(8), 1406-1415. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby119 [ Links ]

Eurelings, L. S.; van Dalen, J. W.; ter Riet, G.; van Charante, E. P. M.; Richard, E.; van Gool, W. A. (2018). Apathy and depressive symptoms in older people and incident myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Clinical Epidemiology, 10, 363-379. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S150915 [ Links ]

Gero, K.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N.; Shirai, K.; Kawachi, I. (2017). Associations of relative deprivation and income rank with depressive symptoms among older adults in Japan. Social Science & Medicine, 189, 138-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.028 [ Links ]

Guedea, M. T. D.; Albuquerque, F. D.; Tróccoli, B. T.; Noriega, J. A. V.; Seabra, M. A. B.; Guedea, R. L. D. (2006). Relationships of subjective well-being, coping strategies and perceived social support in the elderly. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 19(2), 301-308. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722006000200017 [ Links ]

Han, K.-M.; Han, C.; Shin, C.; Jee, H.-J.; An, H.; Yoon, H.-K.; Ko, Y.-H.; Kim, S.-H. (2018). Social capital, socioeconomic status, and depression in community-living elderly. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 98, 133-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.01.002 [ Links ]

Harada, K.; Sugisawa, H.; Sugihara, Y.; Yanagisawa, S.; Shimmei, M. (2018). Social support, negative interactions, and mental health: Evidence of cross-domain buffering effects among older adults in Japan. Research on Aging, 40(4), 388-405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517701446 [ Links ]

He, G.; Xie, J. F.; Zhou, J. D.; Zhong, Z. Q.; Qin, C. X.; Ding, S. Q. (2016). Depression in left-behind elderly in rural China: Prevalence and associated factors. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 16, 638-643. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12518 [ Links ]

Heser, K.; Stein, J.; Luppa, M.; Wiese, B.; Mamone, S.; Weyerer, S.; … Stark, A. (2020). Late-life depressive symptoms are associated with functional impairment cross-sectionally and over time: Results of the AgeMooDe study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(4), 811-820. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby083 [ Links ]

Honjo, K.; Tani, Y.; Saito, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Kondo, K.; Kawachi, I.; Kondo, N. (2018). Living alone or with others and depressive symptoms, and effect modification by residential social cohesion among older adults in Japan: The JAGES longitudinal study. Journal of Epidemiology, 28(7), 315-322. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20170065 [ Links ]

Hu, H.; Cao, Q.; Shi, Z.; Lin, W.; Jiang, H.; Hou, Y. (2018). Social support and depressive symptom disparity between urban and rural older adults in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 237, 104-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.076 [ Links ]

Isaac, L.; Ferreira, C. R.; Ximenes, V. S. (2018). Cuidar de idosos: Um assunto de mulher? Estudos Interdisciplinares em Psicologia, 9(1), 108-125. https://doi.org/10.5433/2236-6407.2016v9n1p108 [ Links ]

Kim, G.; Allen, R. S.; Wang, S. Y.; Park, S.; Perkins, E. A.; Parmelee, P. (2018). The relation between multiple informal caregiving roles and subjective physical and mental health status among older adults: Do racial/ethnic differences exist? The Gerontologist, 59(3), 499-508. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx196 [ Links ]

Laborde-Lahoz, P.; El-Gabalawy, R.; Kinley, J.; Kirwin, P. D.; Sareen, J.; Pietrzak, R. H. (2015). Subsyndromal depression among older adults in the USA: Prevalence, comorbidity, and risk for new-onset psychiatric disorders in late life. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(7), 677-685. [ Links ]

Lampert, C. D. T.; Ferreira, V. R. T. (2018). Factors associated with depressive symptomatology in the elderly. Avaliação Psicológica, 17(2), 205-212. https://doi.org/10.15689/ap.2018.1702.14022.06 [ Links ]

Lawton, M. P.; Brody, E. M. (1969). Assesment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist, 9, 179-85. [ Links ]

Li, C.; Jiang, S.; Li, N.; Zhang, Q. (2018). Influence of social participation on life satisfaction and depression among Chinese elderly: Social support as a mediator. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(3), 345-355. [ Links ]

Lima, A. M. P.; Ramos, J. L. S.; Bezerra, I. M. P.; Rocha, R. P. B.; Batista, H. M. T.; Pinheiro, W. R. (2016). Depression in the elderly: A systematic review of the literature. Revista de Epidemiologia e Controle de Infecção, 6(2), 96-103. https://doi.org/10.17058/reci.v6i2.6427 [ Links ]

Liu, L.; Gou, Z.; Zuo, J. (2016). Social support mediates loneliness and depression in elderly people. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(5), 750-758. [ Links ]

Macedo, J. P.; Dimenstein, M.; Sousa, H. R. D.; Costa, A. P. A. D.; Silva, B. I. D. B. D. (2018). Brazilian scientific production about social support: Trends and invisibilities. Gerais: Revista Interinstitucional de Psicologia, 11(2), 258-278. https://doi.org/10.36298/gerais2019110206 [ Links ]

Maia, C. M. L.; Castro, F. V.; Fonseca, A. M. G.; Fernández, M. I. R. (2016). Redes de apoio social e de suporte social e envelhecimento ativo. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology. Revista INFAD de Psicología, 1(1), 293-306. https://doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2016.n1.v1.279 [ Links ]

Malta, D. C.; Moura, E. C.; Oliveira, M.; Santos, F. P. (2011). Health insurance users: Self-reported morbidity and access to preventive tests according to a telephone survey, Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 27(1), 57-66. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2011000100006 [ Links ]

Mendes-Chiloff, C. L.; Lima, M. C. P.; Torres, A. R.; Santos, J. L. F.; Duarte, Y. O.; Lebrão, M. L.; Cerqueira, A. T. D. A. R. (2019). Depressive symptoms among the elderly in São Paulo city, Brazil: Prevalence and associated factors (SABE Study). Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 21, e180014. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720180014.supl.2 [ Links ]

Nascimento, P. P. P.; Batistoni, S. S. T.; Neri, A. L. (2016). Frailty and depressive symptoms in older adults: Data from the FIBRA study - UNICAMP. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 29, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0033-9 [ Links ]

Neri, A. L.; Vieira, L. A. M. (2013). Social involvement and perceived social support in old age. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia, 16(3), 419-432. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1809-98232013000300002 [ Links ]

Neri, A. L.; Yassuda, M. S.; Araújo, L. F.; Eulálio, M. C.; Cabral, B. E.; Siqueira, M. E. C.; Santos, G. A.; Moura, J. G. A. (2013). Methodology and social, demographic, cognitive, and frailty profiles of community-dwelling elderly from seven Brazilian cities: The FIBRA Study. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 29(4), 778-792. https://www.scielo.br/j/csp/a/xQ65bzxRxMRZ9FpddG344dt/ [ Links ]

Nóbrega, I. R. A. P. D.; Leal, M. C. C.; Marques, A. P. D. O.; Vieira, J. D. C. M. (2015). Fatores associados à depressão em idosos institucionalizados: Revisão integrativa. Saúde em Debate, 39, 536-550. [ Links ]

Paradela, E. M. P.; Lourenço, R. A.; Veras, R. P. (2005). Validation of geriatric depression scale in a general outpatient clinic. Revista de Saúde Pública, 39(6), 918-923. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102005000600008 [ Links ]

Paúl, C. (2017). Envelhecimento activo e redes de suporte social. Sociologia: Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, 15, 275-287. [ Links ]

Polyakova, M.; Sonnabend, N.; Sander, C.; Mergl, R.; Schroeter, M. L.; Schroeder, J.; Schönknecht, P. (2014). Prevalence of minor depression in elderly persons with and without mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152, 28-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.016 [ Links ]

Rabelo, D. F.; Neri, A. L. (2015). Tipos de configuração familiar e condições de saúde física e psicológica em idosos. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 31, 874-884. [ Links ]

Ramos, G. C. F.; Carneiro, J. A.; Barbosa, A. T. F.; Mendonça, J. M. G.; Caldeira, A. P. (2015). Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors among elderly in northern Minas Gerais: A population-based study. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 64(2), 122-131. https://doi.org/10.1590/0047-2085000000067 [ Links ]

Rodrigues, N. O.; Neri, A. L. (2012). Social, individual and programmatic vulnerability among the elderly in the community: Data from the FIBRA study conducted in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 17, 2129-2139. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232012000800023 [ Links ]

Santos, C. A. D.; Ribeiro, A. Q.; Rosa, C. D. O. B.; Ribeiro, R. D. C. L. (2015). Depression, cognitive deficit and factors associated with malnutrition in elderly people with cancer. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 20(3), 751-760. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015203.06252014 [ Links ]

Sengupta, P.; Benjamin, A. I. (2015). Prevalence of depression and associated risk factors among the elderly in urban and rural field practice areas of a tertiary care institution in Ludhiana. Indian Journal of Public Health, 59(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-557X.152845 [ Links ]

Silva, L. L. N. B. D.; Rabelo, D. F. (2017). Affection and conflict in the family, functional capacity and expectation of care of the elderly. Pensando familias, 21, 80-91. [ Links ]

Silva, S. M.; Braido, N. F.; Ottaviani, A. C.; Gesualdo, G. D.; Zazzetta, M. S.; Orlandi, F. S. (2016). Social support of adults and elderly with chronic kidney disease on dialysis. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 24, e2752. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.0411.2752 [ Links ]

Sousa-Muñoz, R. L.; Fernandes Junior, E. D.; Brito, N. D.; Garcia, B. B.; Moreira, I. F. (2013). Association between depressive symptomatology and hospital death in elderly. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 62(3), 177-82. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0047-20852013000300001 [ Links ]

Souza, D. D. S.; Berlese, D. B.; Cunha, G. L. D.; Cabral, S. M.; Santos, G. A. D. (2017). Analysis of the relationship of social support and fragility in elderly syndrome. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 18(2), 420-433. https://doi.org/10.15309/17psd180211 [ Links ]

Ventura, J.; Semedo, D. C.; Paula, S. F.; Silva, M. R. S.; Pelzer, M. T. (2016). Fatores associados a depressão e os cuidados de enfermagem no idoso. Revista de Enfermagem, 12(12), 100-113. [ Links ]

Weissman, J. D.; Russell, D. (2018). Relationships between living arrangements and health status among older adults in the United States, 2009-2014: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(1), 7-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464816655439 [ Links ]

Recebido em 16 de janeiro de 2020

Aceito para publicação em 02 de abril de 2021

Esta pesquisa foi financiada pelo CNPq - Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (processo 555087/2006-9) e pela FAPEMIG - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (processo APQ-01145-14).

This work was supported by CNPq - National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (grant 555087/2006-9), and by FAPEMIG - Foundation for Research of the State of Minas Gerais (grant APQ-01145-14).

Pricila Cristina Correa Ribeiro worked on the conception, design and supervision of data collection of the study; in the analysis and interpretation of the data and in the writing of the article. Felipe Cordeiro Alves worked on the analysis and interpretation of the data and the writing of the article. Roberto Alves Lourenço worked on the conception and delineation of the study and on the critical revision of the final essay of the article.

1 Available in https://www.geronlab.com/projetos-de-pesquisa.html