Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.24 no.1 São Paulo jan./abr. 2022

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPPA13675.en

PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

Construction and evidence of validity of the Positive Discipline parenting skills scale

Construção e evidências de validade da escala de habilidades parentais em Disciplina Positiva

Construcción y evidencias de validez de la escala de habilidades parentales en Disciplina Positiva

Laura C. M. Soares ; José Augusto E. Hernandez

; José Augusto E. Hernandez

Department of Cognitive Psychology and Development, Postgraduate Degree in Social Psychology, Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ)

ABSTRACT

This article presents the construction and evidence of validity of an instrument for measuring parenting skills based on Positive Discipline, an approach that helps parents and caregivers teach life skills to their children. The items were constructed based on a theoretical review of Parenting Styles, Schema Therapy, and Positive Discipline and were subsequently evaluated by five expert judges and five individuals from the target audience. Following these evaluations, eight items were excluded and the others were changed, leading to the pilot version of the Positive Discipline Parenting Skills Scale (Escala de Habilidades Parentais em Disciplina Positiva - EHPDP), represented by 28 items. Data were collected from a sample of 281 mothers with children aged 4-12 years. Exploratory Factor Analysis revealed a structure of 16 items divided into three factors. Cronbach's Alpha and Composite Reliability indicated adequate internal consistency for the instrument. Pearson's correlation revealed evidence of convergent and discriminant validity with the validated Brazilian versions of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale. The results indicate that the EHPDP is a valid and reliable instrument to measure Positive Discipline parenting skills.

Keywords: positive discipline, parenting skills, parenting styles, validity, psychometrics

RESUMO

Este artigo apresenta a construção e evidências de validade de um instrumento para mensurar habilidades parentais baseado na Disciplina Positiva, abordagem que auxilia pais e cuidadores a ensinar habilidades de vida para suas crianças. Os itens foram formulados a partir de revisão teórica sobre estilos parentais, Terapia do Esquema e Disciplina Positiva e posteriormente avaliados por cinco juízas experts e cinco indivíduos do público-alvo. Após as avaliações, oito itens foram excluídos e outros sofreram alterações, chegando-se a uma versão-piloto da Escala de Habilidades Parentais em Disciplina Positiva (EHPDP) com 28 itens. Os dados foram coletados de uma amostra de 281 mães com filhos de 4-12 anos. A análise fatorial exploratória revelou uma estrutura de 16 itens divididos em três fatores. O Alfa de Cronbach e a confiabilidade composta indicaram adequada consistência interna para o instrumento. A correlação de Pearson revelou evidências de validades convergente e discriminante com as versões brasileiras validadas do Questionário de Estilos e Dimensões Parentais e da Escala de Depressão, Ansiedade e Estresse. Os resultados indicam que a EHPDP é um instrumento válido e confiável para mensurar habilidades parentais em Disciplina Positiva.

Palavras-chave: Disciplina Positiva, habilidades parentais, estilos parentais, validade, psicometria

RESUMEN

Este artículo presenta la construcción y evidencias de validez de un instrumento para medir habilidades parentales basado en la Disciplina Positiva, un enfoque que ayuda a los padres y cuidadores a enseñar habilidades para la vida a sus hijos. Los ítems de la escala se formularon en base a una revisión teórica sobre estilos parentales, Terapia de Esquemas y Disciplina Positiva, siendo posteriormente evaluados por cinco jueces expertos y cinco individuos del público destinatario. Después de las evaluaciones, ocho ítems fueron excluidos y otros sufrieron cambios, llegando a la versión piloto de la Escala de Habilidades Parentales en Disciplina Positiva (EHPDP), con 28 ítems. Los datos se obtuvieron de una muestra de 281 madres con niños de 4-12 años. El análisis factorial exploratorio reveló una estructura de 16 ítems divididos en tres factores. El Alfa de Cronbach y la fiabilidad compuesta indicaron una consistencia interna adecuada para el instrumento. La correlación de Pearson reveló evidencia de validez convergente y discriminante con las versiones brasileñas validadas del Cuestionario de Estilos y Dimensiones Parentales y la Escala de Depresión, Ansiedad y Estrés. Los resultados indican que la EHPDP es un instrumento válido y confiable para medir las habilidades parentales en Disciplina Positiva.

Palabras clave: Disciplina Positiva, habilidades parentales, estilos parentales, validez, psicometría

Parent-child relationships and their influence on children's emotional, social, and cognitive development have been the subject of many studies in recent decades (Baumrind, 1966, 1967, 1971; Lamborn et al., 1991; Paiva & Ronzani, 2009; Granja & Mota, 2018). Considering this, Baumrind (1966, 1967) created a theoretical model proposing the existence of three parenting styles, which would be categorized by parental control and affection towards the child. The degree to which parents demonstrate behaviors in these dimensions defines their parenting style as authoritarian, permissive, or authoritative (Baumrind, 1967). The authoritarian style provides little affection and a lot of control, valuing obedience and using punishments; the permissive style is affectionate but avoids setting limits and restrictions; and the authoritative style gives affection while exercising firm control, recognizing the child's interests, and encouraging dialogue (Granja & Mota, 2018; Oliveira et al., 2018).

National and international studies relate the authoritative style to positive aspects of children's development, such as: greater emotional regulation; appropriate social skills and more happiness (Baumrind, 1971); greater social competence and fewer behavior problems (Lamborn et al., 1991); better mental health (Lamborn et al., 1991; Hutz & Bardagi, 2006; Uji et al., 2014); higher levels of optimism (Weber et al., 2003) and well-being (Boeckel & Sarriera, 2006); and lower consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs (Paiva & Ronzani, 2009). Conversely, relationships were found between the other styles and negative aspects of children, such as: poor emotional control; low levels of persistence faced with challenges and confrontation when their desires were not fulfilled (Baumrind, 1971); lower psychosocial competence and less engagement in the school environment (Lamborn et al., 1991); greater psychological dysfunction (Lamborn et al., 1991; Hutz & Bardagi, 2006; Uji et al., 2014); lower levels of optimism (Weber et al., 2003) and well-being (Boeckel & Sarriera, 2006); higher frequency of substance abuse (Lamborn et al., 1991; Paiva & Ronzani, 2009); and higher levels of behavior problems (Lamborn et al., 1991; Tavassolie et al., 2016).

The theoretical advance provided by research investigating the relationship between parenting styles and psychosocial aspects has highlighted the study of correlations between family styles and psychopathologies in the literature. Accordingly, in the 1990s, Jeffrey Young's Schema Therapy emerged, the first clinical model for comprehending parenting styles. This model proposes the existence of 18 maladaptive initial schemas that would develop in childhood and adolescence, based on interactions with punitive, cold, permissive, hypercritical, overprotective, or invalidating family nuclei, leading to the manifestation of psychological disorders in the future (Wainer et al., 2016).

Positive Discipline (PD) was developed by Nelsen (2015) in the 1980s based on Alfred Adler and Rudolf Dreikurs' teachings. Its main purpose is to help parents and caregivers teach their children important life skills by reading books on the subject and participating in training and workshops. Therefore, it can be used as a tool to promote the skills of parents, who could contribute more effectively to the healthy development of their children, which could, in turn, prevent the manifestation of psychological disorders in the future. PD teaches concepts that are quite representative of Baumrind's authoritative style (Carroll & Hamilton, 2016). Both recognize the importance of providing affection and support, respectfully setting boundaries, and helping the child become autonomous. However, PD goes beyond what is proposed by the authoritative style, also proposing interactions that promote the development of important life skills, such as self-awareness, self-regulation, responsibility, problem-solving, and resilience (Glenn & Nelsen, 2010; Nelsen, 2015). Therefore, as this is an approach with a broader repertoire than that predicted by the authoritative style, it can promote the development of other equally important aspects of children, such as socio-emotional skills.

Over the past few decades, many books on PD have been published, and an organization was created, the Positive Discipline Association. The association today has a global presence and is responsible for certifying PD Parent Educators worldwide, who offer the community training and workshops to promote the development of the parenting skills suggested by this approach. However, due to the lack of studies on the subject, very little is known about the effectiveness of the proposed programs, which are taught over a series of meetings, or self-taught from reading books, and other educational materials. Therefore, research must be carried out to investigate whether these training programs for parents are effective, whether parenting style changes are sustained, and for how long. An instrument that measures these practices is needed for this analysis to be possible.

Parenting Styles embrace different forms of parent-child interaction, both favorable for the child's development, such as the authoritative style, and harmful, such as the authoritarian and permissive (Baumrind, 1971). PD is a proposal similar to the authoritative style; that is, it is also beneficial for the development of children (Carroll & Hamilton, 2016). Schema Therapy is a clinical model based on maladaptive schemas that would be developed from harmful interactions between the child and their family/caregivers (Wainer et al., 2016).

Regarding the similarities between the authoritative style and PD, it can be said that both recognize the importance of providing affection/support, of respectfully establishing limits, and of helping the child become autonomous, which are behaviors contrary to characteristics of the authoritarian style, such as the use of physical coercion, punishments, and verbal hostility; and the permissive one, such as indulgence (Nelsen, 2015; Oliveira et al., 2018). The conceptual model of Schema Therapy is divided into five schema domains. These consist of time intervals from early childhood to early adolescence, in which caregivers and the environment are expected to fulfill some psychological demands, also called "fundamental needs", so that the child develops healthy initial schemas (Wainer et al., 2016).

It is important to highlight that both Schema Therapy and PD recognize the existence of children's "fundamental needs", as the first says, or "basic needs", as the second defines them. For Schema Therapy, there are five needs: acceptance and secure attachments; autonomy and competence; realistic limits; respect for aspirations, desires, and individuality; and legitimate expression of emotions (Wainer et al., 2016). Concerning PD, there are four basic needs: a sense of acceptance, connection, and belonging; a sense of autonomy and capability; social and life skills; and firm, gentle discipline (Nelsen, 2018). Therefore, the approaches suggest three common needs: acceptance/connection, autonomy and perceived capability, and the definition of reasonable and respectful limits. Furthermore, although PD does not include in its list of needs the respect for the aspirations, desires, and individuality of the child, nor the legitimate expression of their emotions, it addresses the importance of these two aspects in its books. Therefore, in theoretical terms, PD is fully aligned with what Schema Therapy suggests: children's needs to be fulfilled by their caregivers.

Considering the differences, PD predicts the need for the development of social and life skills, such as self-regulation, self-control, self-discipline, empathy, respect, problem-solving, cooperation, flexibility, among others; and Schema Therapy only foresees self-control and self-discipline, which would be within the domain of impaired autonomy and performance (Glenn & Nelsen, 2010; Nelsen, 2015; Wainer, 2016). Something similar occurs in the authoritative parenting style, which, as mentioned, does not predict the development of these important skills either.

A literature review was carried out in April 2019 in the CAPES journals portal and Google Scholar, aiming to verify the existence of a valid and reliable instrument to assess the parenting skills proposed by PD. The search included the term "Positive Discipline" associated with the term "instrument" or "scale" or "measure" and the term "Nelsen", as well as their equivalents in Portuguese and Spanish. The keywords could be contained anywhere in the article, which could have been published in any year. The literature search resulted in two studies that used the following instruments to measure PD parenting skills: the DISPO questionnaires (Positive Discipline: Evaluation of family responsibility and co-responsibility), by Sánchez et al. (2010), and the Positive Discipline Parenting Scale, by Carroll and Hamilton (2016). However, both presented problems concerning their psychometric properties.

The only statistical analysis performed in the DISPO questionnaires study (Sánchez et al., 2010) was the calculation of Cronbach's Alpha in order to verify the reliability. This calculation was performed based on a sample of six fathers/mothers and another sample of 15 children, in which the results were .68 and .51, respectively, which are considered less than adequate. Furthermore, as the size of these two samples was very small, it was concluded that the evidence generated was not sufficient to attribute reliability to the measure (Hair et al., 2018).

Regarding the Positive Discipline Parenting Scale (Carroll & Hamilton, 2016), its seven items were adapted from an 18-item questionnaire developed in a study by McVittie and Best (2009) to assess the effect of an Adlerian training program for parents. The authors recognize that the items are not able to represent the extension of the construct proposed by PD, which demonstrates the need for a more comprehensive measure. In addition, concerning data analysis, Principal Component Analysis was performed instead of the Exploratory Factor Analysis, which would be the recommended method when there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate how the items of an instrument should be grouped and evaluated (Damásio, 2012), as is the case with PD. Accordingly, a literature review on Parenting Styles, Schema Therapy, and PD was carried out, as well as a review of the psychometric instruments that measure these constructs. Although coming from different areas of psychology, these approaches are similar since they deal with how different forms of child-parent interaction impact the development of children. The literature review made it clear that, although it was not developed with the purpose of being a theoretical approach, but rather as support material for parents concerning bringing up their children, PD has a robust theoretical basis, being consistent with what other approaches to Psychology propose, such as Parental Styles and Schema Therapy.

A review of the psychometric instruments based on parenting styles and Schema Therapy was also carried out, as instruments based on PD had already been reviewed. This review produced the short version of the Parent Perception Questionnaire (Pasquali et al., 2012); and the Brazilian adapted versions of the Parental Demand and Responsiveness Scales (Costa et al., 2000), the Parental Styles Questionnaire (Boeckel & Sarriera, 2005), and the Parental Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire - PSDQ (Oliveira et al., 2018), among others. With regard to the parenting styles proposed by Schema Therapy, the Brazilian version of the Young Parenting Styles Inventory was found (Valentini, 2009).

In order to fill this gap in valid, reliable measures that represent the scope of what is proposed by PD, this article presents the construction of the Positive Discipline Parenting Skills Scale (Escala de Habilidades Parentais em Disciplina Positiva - EHPDP) and the investigation of evidence of validity and reliability. This self-report instrument is for mothers with children aged from 4 to 12 years old, and aims to measure the frequency of certain interactions that have the potential to fulfill their children's basic needs.

Method

Ethical procedures

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (CAAE 16426019.9.0000.5259).

Content Construction and Validity of the EHPDP

Definition of the dimensions and elaboration of the EHPDP items

This review intends to serve as a basis for defining the dimensions of the EHPDP and the elaboration of their respective items. First, it is important to emphasize that PD was not developed to be a theoretical approach, but a set of practices proposed through books and workshops to help parents and caregivers teach their children life skills. Therefore, it was necessary to structure a theory based on what is proposed by this approach to define the instrument's dimensions and elaborate its respective items. A clinical psychologist with experience in parental guidance and a parent educator certified by the Positive Discipline Association carried out this step - the educator was pursuing a Master's degree in a postgraduate course at the time.

Although two foreign instruments constructed with the aim of measuring parental skills in PD were found, neither of them defined dimensions for the instruments. In the Positive Discipline Parenting Scale study (Carroll & Hamilton, 2016), the Principal Component Analysis indicated a three-factor solution; however, the Scree Plot test suggested that a single-factor solution would be more appropriate. The evaluation of factor loadings also indicated that all items loaded heavily in a single factor, except for two, which were excluded, achieving a one-dimensional seven-item version. In the study of the DISPO Questionnaires (Sánchez et al., 2010),28 items were presented; however, the elaboration process of these items is not explained, nor are dimensions mentioned. Furthermore, the factorial validity of the instrument was not evaluated, so there is no information in this regard.

As there is no prior knowledge in relation to the possible dimensions of PD, these were defined based on the information collected in the review of the literature and instruments, as well as on the knowledge and experience of the aforementioned researcher. Accordingly, four dimensions were defined based on the basic needs of children to be fulfilled by their caregivers (Nelsen, 2018): Firm and Gentle Discipline, Acceptance/Importance, Capability/Autonomy, and Social and Life Skills.

Firm and Gentle Discipline is the ability to regulate a child's behavior through a respectful and encouraging attitude (Nelsen, 2015). Acceptance/Importance refers to the ability to make it noticeable to the child that they are accepted, important, and loved (Nelsen, 2015; Wainer et al., 2016). Capability/Autonomy demonstrates the ability to provide children with opportunities to perceive that they are capable and to learn to perform tasks appropriate for their age without the help of adults (Nelsen, 2015; Wainer et al., 2016). Social and Life Skills consist of the ability to assist the child in the development of emotional self-awareness and self-regulation, communication, assessment, responsibility, problem solving, and motivation (Glenn & Nelsen, 2010; Nelsen, 2015).

The items were constructed based on the aforementioned approaches, some of them being inspired by instrument items that measure correlated constructs, such as the questionnaire used in the study by McVittie and Best (2009), the Parental Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (Oliveira et al., 2018) and the DISPO Questionnaires (Sánchez et al., 2010). The first version of the scale had 36 items, nine for each of the four dimensions. Table 1 shows the items from the first version of the EHPDP followed by an indication of the dimension for which they were constructed.

Item analysis by expert judges

Five judges participated in this stage, not including the researcher that created the items, four psychologists with Ph.D. degrees (one of them also a PD parental educator) and a PD trainer certified by the Positive Discipline Association, with a Master's degree, all with in-depth knowledge of the area of parental educational practices and also two with knowledge of Schema Therapy. The evaluators were recruited from a convenience sample, through an invitation letter sent by e-mail. They received a file containing an explanatory text on the PD dimensions and a spreadsheet with the items of the scale, in which they needed to indicate which dimension each item referred to and evaluate them for clarity of language, practical relevance, and theoretical relevance according to a Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (very little) to 5 (very much). In addition, they were asked to make observations for each item in relation to criticisms, opinions, and suggestions for changes that could contribute to the construction of the instrument.

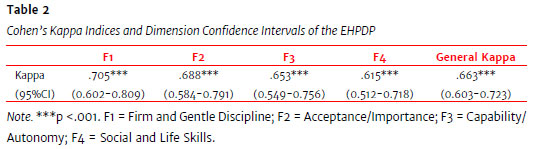

The collected data were analyzed by calculating the Content Validity Coefficient (CVC) (Hernández-Nieto, 2002) to assess the agreement of the judges regarding the level of clarity, practical relevance, and theoretical relevance of the items; and Cohen's Kappa Coefficient to measure the agreement regarding the dimension to which the items belonged. According to Hernández-Nieto (2002), acceptable CVCs must indicate an agreement of 80% among the evaluators. Each of the EHPDP items had CVCs between .8 and 1.0 for the dimensions' clarity of language, practical relevance, and theoretical relevance, and the CVCTotal was .95, .98, and .99, respectively, indicating high agreement among the judges (Table 1).

The data regarding the classification of the items in one of the four dimensions presented were submitted to Cohen's Kappa Coefficient calculation. The overall result (Table 2) indicated substantial agreement (Ranganathan et al., 2017).

Some items generated doubts in the evaluators regarding the dimension to which they belonged, which revealed that they could be related to more than one dimension. This hypothesis was considered during the construction of the items based on the observation that some of the behaviors proposed by PD could fulfill more than one basic need of the children. As the factor analysis to be carried out later could provide more information in this regard, it was decided that the items that aroused these doubts in the judges would remain in the instrument.

The comments led to the removal of six items and the alteration of others. For example, one of the judges pointed out that the item "My child knows that I take them seriously, that is, I not only understand them, I accept, love and respect them" would contain many actions, which could generate doubt in respondents, who would not necessarily agree with all points. Furthermore, it was noticed that, as the item was about the child's perception of their parents, this could generate a conflict regarding the response scale and the instrument as a whole, which would measure the frequency of certain interactions between parents and their children. Therefore, it was decided to exclude the item.

The reversed items "I make threats or promises to my child that I cannot or will not carry out" and "I use physical violence, determine punishments and/or withdraw privileges when my child makes a mistake, misbehaves or does not do well at school" were excluded after comments about the possibility of generating defensiveness in respondents, as these actions are seen as negative/violent by society. In addition, the last item would have many actions, which could impair the respondent's comprehension of it.

The language of some items was also reformulated, such as changing the expression "home work" to "household chores", to avoid the perception that the item referred to schoolwork that a student is required to do at home In addition, the item "When I notice that my child is feeling a negative emotion" was changed to "When I notice that my child is upset..." to avoid difficulty in the target audience comprehending the item.

Item analysis by target audience

A 30-item version of the EHPDP was reviewed by individuals belonging to the target audience to verify whether it was clear, well written, and in accordance with the reality of this population. Three women and two men participated in this stage, aged between 30 and 38 years old, with children aged from 4 to 12 years old, with levels of education from incomplete elementary school to higher education, residing in the city of Rio de Janeiro, with the sample composed by convenience.

In this stage, the respondents were asked to explain what they understood by each item in their own words. When they did not understand an idea or expression, it was explained in other words. In these cases, after understanding the meaning of the idea or expression, they were asked to suggest more adequate synonyms or changes in the item's structure in order to ensure its comprehension by the participant.

The results led to changes in the wording of several items, such as changing the expression "if frustrated" to "when upset" and from "I offer rewards" to "I do what she/he wants". Furthermore, the items "I encourage my child to express him/herself even when they disagree with me" and "I comfort my child when he or she is sad" were excluded due to the difficulty of comprehension by the public with less schooling, culminating in the pilot version of the EHPDP, with 28 items.

Evidence of validity and reliability for the EHPDP

Participants

The participants of this study were 281 Brazilian mothers, aged between 21 and 54 (M = 38.5; SD = 5.2), with at least one child between 4 and 12 years of age, who completed a virtual form after being recruited through social media posts. All participants consented to have their data used in this study, with 76.5% being from the Southeast; 7.1% from the Central-West; 6.4% from the Northeast; 5.0% from the South; 2.1% from the North; and 2.8% living abroad. Among the participants, 87.2% were in a stable relationship, cohabiting with their partner; 2.8% were in a stable relationship, not living with their partner; and 10.0% were not in a relationship at the time of data collection. The number of children ranged from one to nine (M = 1.8; SD = 0.83) and the duration of the relationship from 2 to 360 months (M = 167.5; SD = 64.60). With regard to education, 2.1% had completed high school, 6.0% had incomplete higher education, 30.6% had completed higher education, 8.5% had incomplete postgraduate studies, and 52.7% had completed postgraduate studies.

Instruments

Data were collected through a self-administered form consisting of three psychometric instruments and a sociodemographic questionnaire. After content validation, the EHPDP pilot version contained 28 items distributed in four dimensions: Firm and Gentle Discipline, Acceptance/Importance, Capability/Autonomy, and Social and Life Skills. Respondents used a five-point Likert-type scale to assess items from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

A Brazilian adaptation by Oliveira et al. (2018) of the Parental Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire was also used. This instrument is based on the Baumrind model and has 32 items divided into seven dimensions and three parenting styles, evaluated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The Authoritative style includes 15 items divided into three dimensions (Support and Affection, Regulation, and Autonomy), the Authoritarian, 12 items divided into three dimensions (Physical Coercion, Verbal Hostility, and Punishment) and the Permissive, five items in a single dimension (Indulgence).

Oliveira et al. (2018) found relatively good validity and reliability results for the short version of the PSDQ with a sample of mothers with a mean age of 38.44 (SD = ±6.51), with children aged between three and 18 years old. Confirmatory Factor Analysis indicated a model with three second-order factors. Cronbach's alpha was .75 for the complete questionnaire; however, the reliability indices ranged from .59 to .85 between the first and second-order factors. Furthermore, the PSDQ showed convergent validity with the Parental Styles Inventory (Gomide, 2006). Oliveira et al. (2018) considered the PSDQ effective and reliable to assess the different parenting styles in the Brazilian population.

Although some factors of the PSDQ did not present acceptable internal consistency indices, this instrument was chosen to analyze the convergent validity of the EHPDP as it is the most appropriate in the Brazilian context to measure Baumrind's authoritative style. As PD teaches concepts that are quite representative of this style (Carroll & Hamilton, 2016), strong positive correlations were expected between the EHPDP and the Authoritative dimension of the PSDQ. Furthermore, a negative correlation was expected between the dimensions of the EHPDP and the dimensions of the authoritarian and permissive styles of the PSDQ, as PD opposes the practice of parental interactions characteristic of these styles (Nelsen, 2015).

A Brazilian adaptation of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21) by Martins et al. (2019) was also used. The DASS-21 measures Negative Affectivity, consisting of 21 items, equally divided into three subscales: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Respondents have to indicate how much each item applied to their reality in the previous week using a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 ("It did not apply at all") to 3 ("It applied a lot or most of the time"). For this study, some changes were made to this version. The wording of two items was changed, the period considered to assess the symptoms described was the previous month, and a five-point Likert-type scale was used, ranging from 1 ("Never") to 5 ("Always").

In the study by Martins et al. (2019), the scores of university students aged 18 to 35 years old (M = 21.13; SD = ±2.81), using Confirmatory Factor Analysis, showed a good general fit to the theoretical model of three oblique factors of the DASS-21. However, the high correlation between them indicated insufficient discriminative validity. A hierarchical model with one overall factor (Negative Affectivity) was tested, revealing a good general fit to the data and invariance between men and women. For all models tested, the internal consistencies, measured by Cronbach's Alpha and Composite Reliability, were higher than .87 for all dimensions of the DASS-21. Zanon et al. (2020) tested a bifactor model for the DASS-21, and the results indicated the predominance of one overall factor for the measure. This instrument was used to generate evidence of discriminant validity for the EHPDP because negative affectivity and PD parenting skills are very different constructs; therefore, they should not be associated. Furthermore, based on studies that found relationships between parenting styles and practices and psychological aspects of parents (Mateus, 2016; Rodrigues & Nogueira, 2016; Borre & Kliewer, 2014), it was expected that the dimensions of the EHPDP would present negative correlations with the Negative Affectivity measured by the DASS-21.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using the Factor Analysis version 10.10.03 software. The Hull method was used to support the decision regarding the number of factors to extract (Auerswald & Moshagen, 2019). The extraction method used was Minimum Rank Factor Analysis (MRFA) (Shapiro & ten Berge, 2002) in a polychoric correlation matrix with Promax rotation. Reliability was verified using Cronbach's Alpha and Composite Reliability. Furthermore, to generate evidence of convergent and discriminant validity for the EHPDP, the relationships between its dimensions and those of the PSDQ and DASS-21 were evaluated, using Pearson's Correlation Coefficient.

Results

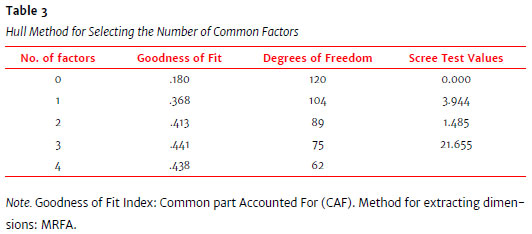

In the preliminary analyses, two items presented extremely high asymmetry and kurtosis indices, leading to them being excluded from the EFA. Even with this, the multivariate distribution of the scores of the remaining 26 items was not normal (Mardia's index = 392.56; CR = 22.94; p <.001). However, observation of the univariate distribution of the scores revealed that asymmetry and kurtosis ranged between <±2 and <±7, respectively, which does not represent an extreme violation of normality (Finney & DeStefano, 2013). Next, an EFA sequence was performed from a polychoric correlation matrix. The factor retention method based on eigenvalues >1 indicated the presence of four factors. However, Hull's method (Auerswald & Moshagen, 2019) recommended extracting three factors for the EHPDP (Table 3).

After fulfilling the three-factor recommendation, five items were excluded due to having factor loadings <.32, three items for simultaneously loading in more than one factor, and two items for loading in factors not previously designated or not proper, as indicated by Hair et al. (2018). The Bartlett Test showed χ2 (120) = 2.445.50, p <.001, and the KMO Test = .82, results that revealed the adequacy of the correlation matrix of this sample for factorization.

The three-factor solution of the EFA for the EHPDP, identified as Social and Life Skills, Acceptance/Importance, and Capability/Autonomy, revealed a total common variance of 12.23, with a common explained variance of 8.94 (73.08%) of the total common variance. The common unexplained variance was 3.29. The 16 items of the EHPDP saturated stronger in theoretically coherent factors. The reliability of the dimensions of the EHPDP, represented by internal consistency and measured by Cronbach's Alpha and Composite Reliability, presented adequate values (Table 4).

The EFA revealed that the Firm and Gentle Discipline dimension was not included in the solution found. Of the six items constructed for this dimension present in the version used in the data collection, four were excluded for presenting insufficient factor loadings and one for loading in more than one factor. In addition, although the item "I let my child participate in the creation of house/family rules when appropriate" was also initially constructed to represent it, it presented a factor loading in the Capability/Autonomy dimension, becoming part of this dimension. After further analysis of the item, it was realized that, although it dealt with rules, which would be a theme relevant to the Firm and Gentle Discipline dimension, it could be related to the development of capability and autonomy by allowing the child to practice the act of defining rules.

Two other items loaded in factors different from those for which they were initially constructed. The items "When my child does poorly at school, I try to show that with commitment and dedication it is possible to achieve better results" and "I let my child choose things like clothes, toys and/or leisure activities, offering limited options that I consider adequate" were constructed for the Capability/Autonomy dimension; however, the first loaded in the Social and Life Skills dimension and the second in the Acceptance/Importance dimension.

As mentioned, one or more items were expected to load in factors different from those for which they were constructed since, in the content validation stage, some judges reported that they were in doubt when classifying the dimension of certain items. For example, the item "I let my child choose things such as clothes, toys and/or leisure activities, offering limited options that I consider appropriate" could help develop autonomy and capability by allowing the child to make choices. However, it could also strengthen the sense of Acceptance/Importance by showing that parents take their interests into account, which was confirmed by the EFA since the item loaded in this factor.

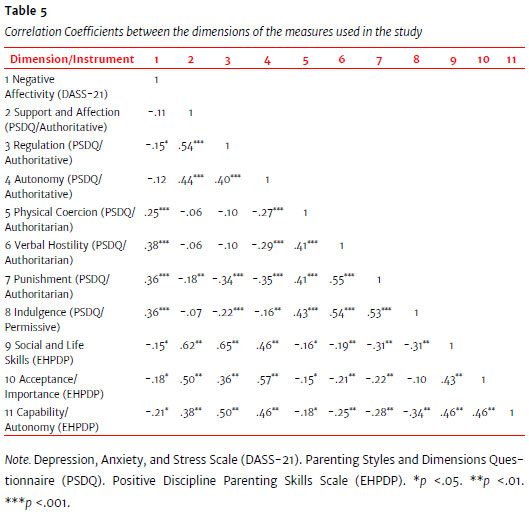

The correlations between the dimensions of the EHPDP and the dimensions of the PSDQ and DASS-21, analyzed using Pearson's Correlation Coefficient, are presented in Table 5.

As expected, statistically significant positive correlations of strong and moderate magnitude were found between the EHPDP dimensions and the dimensions of the authoritative style of the PSDQ, demonstrating evidence of convergent validity for the constructed scale. Negative correlations of moderate and weak magnitudes were also found between the dimensions of the EHPDP and the dimensions of the Authoritarian and Permissive styles of the PSDQ, some of which were significant. Regarding the correlations between the dimensions of the EHPDP and Negative Affectivity, non-significant, negative and weak relationships were found between them, which indicates discriminant validity for the EHPDP in relation to the DASS-21.

Although it was not the objective of this study to analyze the correlations between the dimensions of the PSDQ and the DASS-21, it should be highlighted that non-significant, negative, and weak relationships were found between the Authoritative (PSDQ) and Negative Affectivity (DASS-21) dimensions; and highly significant positive relationships were found between Negative Affectivity and the Authoritarian and Permissive styles of the PSDQ, with one correlation being weak and three being moderate.

Discussion

The present study aimed to construct a measure of PD parenting skills and to investigate its evidence of validity and reliability since similar scales constructed in Brazil or adapted from other languages were not found in the national literature, while the instruments that were found in the international literature used methodologies that raised questions regarding their validity. The process of preparing the items was based on the knowledge of a researcher about PD, Parenting Styles and Schema Therapy and on her experience in individual or group parenting guidance, as well as on a review of the literature and psychometric instruments referring to the aforementioned approaches. This review also provided theoretical support for PD, which was elaborated in the form of manuals for mothers and fathers and not as a theoretical-technical framework, particularly considering the similarities in relation to the authoritative style and the fundamental needs foreseen by Schema Therapy (Carroll & Hamilton, 2016; Wainer et al., 2016).

Validity refers to the degree to which an instrument accurately represents the construct it aims to measure (Hair et al., 2018). The analysis of the judges, the calculation of the CVC and Cohen's Kappa Coefficient, and the target audience analysis provided evidence of content validity for the EHPDP. The EFA indicated evidence of factor validity and the correlation tests of the EHPDP with the PSDQ and the DASS-21 indicated evidence of convergent and discriminant validity. These validities demonstrate that the EHPDP represents the PD parenting skills construct.

Reliability is the ability of an instrument to consistently reproduce a result in time and space (Souza et al., 2017). Internal consistency, measured by Cronbach's Alpha, is generally considered acceptable when above .70 (Hair et al., 2018). In this study, this criterion was fulfilled by the Social and Life Skills (.79) and Capability/Autonomy (.81) dimensions, but not by the Acceptance/Importance dimension (.67). However, some researchers consider coefficients from .60 to .70 the lowest limit of acceptability (Hair et al., 2018). Therefore, it can be said that the EHPDP fulfilled this criterion, providing evidence of the instrument's reliability.

The results found led to a final version of the EHPDP with 16 items divided into three dimensions, with six items in the Social and Life Skills dimension, four in the Acceptance/Importance dimension and six in the Capability/Autonomy dimension. The dimensions reflect the children's basic needs that need to be fulfilled by their caregivers.

Interactions that stimulate the naming and acceptance of emotions, problem-solving, motivation, and evaluation are found in the Social and Life Skills dimension (Glenn & Nelsen, 2010; Nelsen, 2015). The Acceptance/Importance dimension, on the other hand, contemplates interactions that promote the perception that the child's preferences and interests are respected and that their caregivers seek to be with them and do pleasurable things together, strengthening the belief that they are accepted and important (Glenn & Nelsen; Nelsen, 2015; Wainer et al., 2016). In turn, the Capability/Autonomy dimension includes interactions in which the child has the opportunity to develop their autonomy and the belief that they are capable, such as through the practice of activities alone and/or with clear monitoring/guidance of the parents (Glenn & Nelsen, 2010; Nelsen, 2015; Wainer et al., 2016).

The negative correlations of moderate and weak magnitudes found between the dimensions of the EHPDP and the dimensions of the Authoritarian and Permissive styles of the PSDQ, some of them significant, demonstrate consistency with the PD proposal. According to Nelsen (2015), PD moves away from rigidity and permissiveness, which are characteristics of the authoritarian and permissive styles, respectively. Non-significant, negative, and weak relationships were also found between the Authoritative (PSDQ) and Negative Affectivity (DASS-21) dimensions; and very significant positive relationships between the Negative Affectivity and the Authoritarian and Permissive styles of the PSDQ. Similar results were found by Mateus (2016), between the Firm Style (authoritative) and the Anxiety and Insomnia dimension, the Authoritarian Style and the Anxiety and Insomnia and Severe Depression dimensions, and the Permissive Style and the Anxiety and Insomnia dimension. These results suggest that there are relationships between the way parenting is exercised and the psychological aspects of parents.

Impacts on caregivers' mental health could compromise their ability to exercise the parental role (Borre & Kliewer, 2014), leading to the use of authoritarian and permissive practices. On the other hand, negative parenting styles and practices could represent a risk factor for parents' mental health. As children of authoritarian and permissive parents tend to have more behavior problems (Lamborn et al., 1991; Tavassolie et al., 2016), parent-child interactions based on this approach tend to be more stressful for parents, which could harm their mental health. Future studies will be needed to investigate the dynamics between the variables "parenting styles" and "mental health", allowing for a better understanding of the importance of psychological support and training in parenting skills in the lives of the individuals who practice parenting.

Although evidence of validity and reliability was found for the constructed measure, it is also important to highlight the limitations of this study. First, it should be noted that the theoretical proposal of PD suggests the existence of four dimensions (Nelsen, 2018) and that the results of this study found only three dimensions adequate for the theory. The operationalization of the Firm and Gentle Discipline dimension proved to be more challenging than the others, which may have led to the construction of items that did not represent it. PD proposes that mothers and fathers should be firm and gentle simultaneously, making the operationalization of behavioral categories into items more complex. Therefore, it is recommended that new scientific endeavors produce and test new items for the Firm and Gentle Discipline dimension, contemplating interactions in which caregivers seek to regulate the child's behavior through the firm and gentle establishment of limits. Accordingly, it is expected that a version of the EHPDP will be constructed that can represent even more extensively what is proposed by PD.

Regarding the sample, although the data collection included mothers and fathers, the current sample consisted of mothers, as the percentage of male participants was very low (11%). A systematic analysis by Ruiz-Zaldibar et al. (2018) on parental competence and intervention strategies found 15 studies conducted in North America, Europe, and Asia, of which four included only mothers in their samples, one excluded the fathers in the analysis because they represented 6% of the participants and, in the others, with samples of fathers and mothers, the representation of the female sex was 90% in all. This demonstrates that the difficulty of finding male participants is a recurrent issue in research related to parenting. Furthermore, the participants' level of education was not representative of the Brazilian population.

It is recommended that future studies also include fathers and other types of caregivers, with different levels of education, in order to ensure samples that are more representative of Brazilian family structures. It is also suggested that new studies address samples that include more respondents and have a wider coverage of the national territory.

The construction and analysis of the evidence of validity of the EHPDP represents an important contribution in the evaluation of the interactions of mothers with their children. The scale may fill a gap in the national and international literature regarding measures of PD parenting skills. Furthermore, the usefulness of measures of parenting skills is not restricted to research. They can also be used in the clinical context of parenting guidance and parenting skills training for groups, allowing a quick assessment of the occurrence and frequency of positive parent-child interactions. With this, psychologists will be able to provide more accurate parental guidance, facilitating the increase in the repertoire of skills that promote the children's social, emotional, and cognitive development.

Finally, it should be highlighted that the existence of a valid and reliable instrument to measure PD parenting skills will allow future studies to investigate whether the parenting training proposed by PD is capable of promoting the development of parenting skills in its participants. If so, it will also be possible to assess whether these skills can be maintained over time.

References

Auerswald, M., & Moshagen, M. (2019). How to determine the number of factors to retain in exploratory factor analysis: A comparison of extraction methods under realistic conditions. Psychological Methods, 24(4),468-491. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000200 [ Links ]

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of Authoritative Parental Control on Child Behavior. Child Development, 37(4),887-907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126611 [ Links ]

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75(1),43-88. [ Links ]

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4(1, Pt. 2),1-103. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0030372 [ Links ]

Boeckel, M. G., & Sarriera, J. C. (2005). Análise fatorial do Questionário de Estilos Parentais (PAQ) em uma amostra de adultos jovens universitários. Psico-USF, 10(1),1-9. [ Links ]

Boeckel, M. G., & Sarriera, J. C. (2006). Estilos parentais, estilos atribucionais e bem-estar psicológico em jovens universitários. Revista Brasileira Crescimento Desenvolvimento Humano, 16,53-65. [ Links ]

Carroll, P., & Hamilton, W. K. (2016). Positive Discipline Parenting Scale: Reliability and validity of a measure. Journal of Individual Psychology, 72(1),60-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jip.2016.0002 [ Links ]

Costa, F. T., Teixeira, M. A. P., & Gomes, W. B. (2000). Responsividade e exigência: Duas escalas para avaliar estilos parentais. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 13(3),465-473. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722000000300014 [ Links ]

Damásio, B. F. (2012). Uso da análise fatorial exploratória em psicologia. Avaliação Psicológica, 11(2),213- 228. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1677-04712012000200007 &lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Finney, S. J., & DeStefano, C. (2013). Non-normal and Categorical Data in Structural Equation Modeling. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural Equation Modeling: a second course (pp. 269-314). Greenwich, Connecticut: IAP. [ Links ]

Glenn, H. S., & Nelsen, J. (2010). Raising self-reliant children in a self-indulgent world: Seven building blocks for developing capable young people. Prima Publishing and Communications. [ Links ]

Gomide, P. I. C. (2006). Inventário de Estilos Parentais - IEP. Vozes. [ Links ]

Granja, M. B., & Mota, C. P. (2018). Estilos parentais, adaptação académica e bem-estar psicológico em jovens adultos. Análise Psicológica, 36(3),31-326. https://dx.doi.org/10.14417/ap.1415 [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. C. (2018). Multivariate Data Analysis. Cengage Learning EMEA. [ Links ]

Hernández-Nieto, R. A. (2002). Contribuciones al análisis estadístico. Universidad de Los Andes/IESINFO. [ Links ]

Hutz, C. S., & Bardagi, M. P. (2006). Indecisão profissional, ansiedade e depressão na adolescência: A influência dos estilos parentais. Psico-USF, 11(1),65-73. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712006000100008 [ Links ]

Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development, 62(5),1049-1065. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1131151 [ Links ]

Martins, B. G., Silva, W. R., Maroco, J., & Campos, J. A. D. B. (2019). Escala de Depressão, Ansiedade e Estresse: propriedades psicométricas e prevalência das afetividades. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 68(1),32-41. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0047-2085000000222 [ Links ]

Mateus, I. S. M. (2016). Relação entre os Estilos e práticas Parentais e Saúde mental. Um Estudo com a População Geral. [Unpublished Master's dissertation]. Universidade do Algarve. [ Links ]

McVittie, J., & Best, A. (2009). The impact of Adlerian-based parenting classes on self-reported parental behavior. Journal of Individual Psychology, 65(3),264. [ Links ]

Nelsen, J. (2015). Disciplina Positiva. Manole. [ Links ]

Nelsen, J., Erwin, C., & Duffy, R. A. (2018). Disciplina Positiva para crianças de 0 a 3 anos. Manole. [ Links ]

Oliveira, T. D., Costa, D. S., Albuquerque, M. R., Malloy-Diniz, L. F., Miranda, D. M., & de Paula, J. J. (2018). Cross-cultural adaptation, validity, and reliability of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire - Short Version (PSDQ) for use in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 40(4),410-419. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2314 [ Links ]

Paiva, F. & Ronzani, T. (2009). Estilos parentais e consumo de drogas entre adolescentes: Revisão sistemática. Psicologia em Estudo, 14(1),177-183. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722009000100021 [ Links ]

Pasquali, L., Gouveia, V. V., Santos, W. S., Fonsêca, P. N., Andrade, J. M., & Lima, T. J. S. (2012). Questionário de Percepção dos Pais: Evidências de uma medida de estilos. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 22(52),155-164. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X2012000200002 [ Links ]

Ranganathan, P., Pramesh, C. S., & Aggarwal, R. (2017). Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Measures of agreement. Perspectives in clinical research, 8(4),187-191. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.PICR_123_17 [ Links ]

Rodrigues, O. M. P. R., & Nogueira, S. C. (2016). Práticas Educativas e Indicadores de Ansiedade, Depressão e Estresse Maternos. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 32(1),35-44. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-37722016012293035044 [ Links ]

Ruiz-Zaldibar, Cayetana, Serrano-Monzó, Inmaculada, & Mujika, Agurtzane. (2018). Programas de competência dos pais para promover parentalidade positiva e estilos de vida saudáveis em crianças: Uma análise sistemática. Jornal de Pediatria, 94(3),238-250. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2017.07.019 [ Links ]

Sánchez, J. J. M, Martínez, M. E. de J., Martínez, M. C. R., & Correa, A. G. (2010). Análisis de las propriedades psicométricas de los cuestinarios D.I.S.P.O. (Disciplina Positiva: Evaluación de la responsabilidad y corresponsabilidad familiar). International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 3(1),591-600. [ Links ]

Shapiro, A., & ten Berge, J. M. F. (2002). Statistical Inference of Minimum Rank Factor Analysis. Psychometrika, 67(1),79-94. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02294710 [ Links ]

Souza, A. C. de, Alexandre, N. M. C., & Guirardello, E. de B. (2017). Propriedades psicométricas na avaliação de instrumentos: avaliação da confiabilidade e da validade. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 26(3),649-659. https://doi.org/10.5123/s1679-49742017000300022 [ Links ]

Tavassolie, T., Dudding, S., Madigan, A. L., Thorvardarson, E., & Winsler, A. (2016). Differences in Perceived Parenting Style between Mothers and Fathers: Implications for Child Outcomes and Marital Conflict. J Child Fam Stud, 25,2055-2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0376-y [ Links ]

Uji, M., Sakamoto, A., Adachi, K., & Kitamura, T. (2014) The impact of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting styles on children's later mental health in Japan: Focusing on parent and child gender. J Child Fam Stud, 23,293-302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9740-3 [ Links ]

Valentini, F. (2009). Estudo das propriedades psicométricas do Inventário de Estilos Parentais de Young no Brasil. [Unpublished Master's dissertation]. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. [ Links ]

Wainer, R., Paim, K., Erdos, R., & Andriola, R. (orgs.). (2016). Terapia cognitiva focada em esquemas: integração em psicoterapia. Artmed. [ Links ]

Weber, L., Brandenburg, O., & Viezzer, A. P. (2003). A relação entre o estilo parental e o otimismo da criança. Psico-USF, 8(1),71-79. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712003000100010 [ Links ]

Zanon, C., Brenner, R. E., Baptista, M. N., Vogel, D. L., Rubin, M., Al-Darmaki, F. R., Gonçalves, M., Heath, P. J., Liao, H. Y., Mackenzie, C. S., Topkaya, N., Wade, N. G., & Zlati, A. (2020). Examining the Dimensionality, Reliability, and Invariance of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) Across Eight Countries. Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191119887449 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

José Augusto Evangelho Hernandez

Rua São Francisco Xavier, 524, 10º andar, sala 10028D, Maracanã

Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. CEP 20050-900

E-mail: hernandez.uerj@gmail.com

Received: July 26th, 2020

Accepted: June 15th, 2021