Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.24 no.1 São Paulo jan./abr. 2022

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPHD13325.en

HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

Self-injury in adolescence from the bioecological perspective of human development

Autolesão na adolescência sob a perspectiva bioecológica de desenvolvimento humano

La autolesión en la adolescencia desde una perspectiva bioecológica del desarrollo humano

Manuela A. da S. SantoI ; Débora Dalbosco Dell'AglioI,II

; Débora Dalbosco Dell'AglioI,II

IDepartment of Psychology, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS)

IIPostgraduate Program in Education, La Salle University (Unilasalle)

ABSTRACT

This exploratory qualitative study analyzed the characteristics of the self-injury behavior and the support network of four adolescents, between 13 and 17 years sold, attended by a Center for Psychosocial Attention. Data were collected from the care center records, a semi-structured interview and the application of the Map of the Five Fields. From a bioecological perspective, distal risk factors were identified: family mental illness, history of intrafamily violence, and invalidating family environment; intrapersonal risk factors: feelings of guilt, shame, hopelessness, and emptiness; interpersonal vulnerability factors: social isolation and difficulty of emotional expression; and stressful factors: victimization by peers, conflicts with the family, gender transition, and death of family members. The protection factors identified were school, health service, and extended family contexts, in addition to the internet and friendships. Future studies can analyze the mediating and moderating role of protective factors in self-injury, subsidizing preventive actions.

Keywords: self-injury, adolescence, bioecological development, support networks, mental health

RESUMO

Este estudo qualitativo exploratório analisou as características do comportamento autolesivo e da rede de apoio de quatro adolescentes, entre 13 e 17 anos, atendidos em um Centro de Atenção Psicossocial. Os dados foram coletados do prontuário, de uma entrevista semiestruturada e aplicação do Mapa dos Cinco Campos. A partir de uma perspectiva bioecológica, identificaram-se fatores de risco distais: doença mental familiar, histórico de violência intrafamiliar pregressa e ambiente familiar invalidante; fatores de risco intrapessoais: sentimentos de culpa, vergonha, desesperança e vazio; fatores de vulnerabilidade interpessoais: isolamento social e dificuldade de expressão emocional; e fatores estressores: vitimização por pares, conflitos familiares, transição de gênero e morte de familiares. Os fatores de proteção identificados foram os contextos escolar, serviço de saúde e família extensa, além da internet e amizades. Sugere-se que estudos futuros analisem o papel mediador e moderador dos fatores de proteção na autolesão, subsidiando ações de prevenção.

Palavras-chave: autolesão, adolescência, desenvolvimento bioecológico, redes de apoio, saúde mental

RESUMEN

Este estudio cualitativo exploratorio analizó las características del comportamiento de autolesión y de redes de apoyo de cuatro adolescentes, entre 13 y 17 años, atendidos en un Centro de Atención Psicosocial. Los datos se recogieron de los registros del centro de atención, una entrevista semiestructurada y aplicación del Mapa de los Cinco Campos. Desde una perspectiva bioecológica, se identificaron factores de riesgo distales: enfermedades mentales familiares, violencia intrafamiliar y entorno familiar invalidante; factores de riesgo intrapersonal: sentimientos de culpa, vergüenza, desesperanza y vacío; factores de vulnerabilidad interpersonal: aislamiento social y dificultad de expresión emocional; y factores de estrés: bullying, conflictos familiares, transición de género y muerte de parientes. Los factores de protección identificados fueron los contextos escolar, servicio de salud y familia extendida, así como la internet y las amistades. Futuros estudios pueden analizar el papel mediador y moderador de los factores de protección en la autolesión, subvencionando acciones preventivas.

Palabras clave: autolesión, adolescencia, desarrollo bioecológico, redes de apoyo, salud mental

Adolescence is a specific stage of the life cycle, with typical characteristics and unique experiences, during which biological, cognitive, and social changes can make adolescents a priority audience for interventions in the healthcare area (Tomé et al., 2015). Insofar, this is justified as the need for adaptation towards these biopsychosocial transformations allows adolescents to exhibit risky behaviors, that is, to experience situations and resources potentially harmful to their health (Zappe & Dell'Aglio, 2016).

Among the risk behaviors, self-injurious behavior in adolescents can be highlighted, which is defined as a way to harm and/or attack their own body, with objects or substances, with or without the intention of death (Turecki & Brent, 2016). One of the biggest challenges found in the literature regarding self-injury is to differentiate it from suicide attempts. While some authors only consider self-injury without the presence of a suicidal intention, others approach these phenomena as part of the same continuum (ranging from self-injurious ideation to consummated suicide), so that, by differentiating them completely, one can underestimate the risks and invest insufficient resources for treatment and prevention (Turecki & Brent, 2016). In addition, studies in the area show that, in practice, suicide attempts and self-harm are overlapping behavioral characteristics since they can be presented at different times or at the same time; therefore, self-harm can be considered a consistent risk factor for future suicide attempts (Giletta et al., 2015; Turecki & Brent, 2016).

Still, many efforts made by the science community aim to understand the main motivations of this phenomenon (Fonseca et al., 2018). Some hypotheses about the role that self-harm plays in adolescents' lives were explored and described by Nock (2009), such as emotional regulation, social communication/signaling, emotional pain analgesia, self-punishment, social learning, and pragmatism.

At the same time, characteristics of the history of adolescents who exhibit this behavior and the contexts in which they interact must be observed. Self-injury in clinical and non-clinical samples, for example, can be manifested in different ways and take different courses. In the presence of mental disorders, self-injury can begin at an earlier age, occurring more frequently and presenting more severe injuries (Tschan et al., 2015). However, in general, most adolescents who commit self-harm have common risk factors, such as situations of abuse in their childhood, a weak supportive network, a history with psychopathologies, victimization by peers, genetic predisposition, and high emotional reactivity (Nock, 2009).

Thus, it is necessary to understand that the interaction between these multiple factors - and not each one isolated - can lead to self-injury. Therefore, risk behaviors should be assessed according to the context of each adolescent, considering their supportive networks, especially peer and family groups (Tomé et al., 2015).

In adolescence, relationships between peers become more significant, and these experiences of friendship and companionship can be considered protection mechanisms (Tomé et al., 2015; Briggs et al., 2017). Adolescents start to assume the behaviors and habits of others in order to feel integrated and well accepted in this new environment (Zappe & Dell'Aglio, 2016). However, Briggs et al. (2017) point out that the role of the peer group is often underestimated in the adolescents' suicidal behavior, as friends can either protect from or increase the risk of self-injurious behavior.

Although there is a natural tendency to get closer to peers in adolescence, as the first nucleus of socialization, the family group can provide key elements for development by establishing rules and limits, positive models, and instrumentalization of autonomy (Tomé et al., 2015). However, self-injurious behavior has been associated with more critical and hostile parenting approaches and higher levels of stress between parents (Tschan et al., 2015). In addition, an invalidating environment, that is, a family context marked by relationships that arbitrarily avoid, deny or reject an individual's emotions, can contribute to greater emotional reactivity and greater susceptibility to self-harm behaviors (Crowell et al., 2013).

Even though physical damage is more evident than emotional aspects of self-injury amongst adolescents, these also require attention. Some studies have already shown that self-injurious episodes are commonly associated with feelings of loneliness, shame, self-criticism, and guilt (Tschan et al., 2015), and hurting their own body could mean a way for teenagers to relieve the anguish and deal with aversive situations (Turecki & Brent, 2016). For this reason, it is important to understand not only the act itself or the physical damage caused but also the underlying feelings, the contextual and precipitating factors in the life of the self-harming adolescent (Nock, 2009). Thus, due to the complexity of the phenomenon and the multiple variables interacting in the act of self-injury, it is necessary to use theoretical approaches that cover the biopsychosocial dimension of adolescents with risky behavior.

The bioecological model of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 2011) allows understanding the constant and reciprocal interaction of the developing beings with the systems - both direct and indirect - to which they belong. For that, the process-person-context-time (PPCT) model was proposed. The process refers to the interrelationships established by the people with whom a person lives through the systems and throughout the life cycle, which create reciprocal interactions that are progressively more complex. The person is the dimension that includes the biopsychosocial characteristics of a human being, which affects and is affected by the relationships established with the environment at all levels of the systems. The context involves the multiplicity of environments in which a person is inserted and can be understood as microsystems (immediate environments), mesosystems (interaction between microsystems), exosystems (environments in which there is no direct contact, yet they influence the developing being), and macrosystem (cultural and moral values). Finally, we have time as a dimension with a continuum of transformations and constancies throughout the cycle of life (Bronfenbrenner, 2011).

Nock (2009) proposed an integrative theoretical model aligned with bioecological precepts, which includes a complexity of risk variables - both distal and proximal - that are part of the adolescent's self-injurious conduct. The author suggests that the relationship and the sum between distal risk factors result in intrapersonal (low tolerance to stress and aversive emotions and cognitions) and interpersonal (low ability to solve problems and lag in communication skills) vulnerability factors. Consequently, such factors result in a low tolerance to stress, leading to self-injury - a faster and more effective way to regulate affective experiences and aversive social situations (Nock, 2009).

Both the bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2011) and the integrative model of Nock (2009) demonstrate the importance of studying phenomena such as self-injury through a systemic, interactionist, and relational perspective. Although an individual's psychological and emotional factors are relevant to study self-injurious behaviors, it is also necessary to consider how the stage of development, the social and domestic context, and the supportive networks will impact their trajectory.

Thus, the objective of this study was to analyze the characteristics of the self-injurious behavior of four adolescents assisted by a Child and Adolescent Psychosocial Care Center (CAPS IJ), as well as the characteristics of their support networks. This cross-sectional qualitative exploratory study, with a multiple case study delimitation (Yin, 2005), also sought to understand adolescents' personal, domestic, and mesosystemic characteristics.

Method

Participants

The participants were composed of a group of four adolescents who were being assisted at a CAPS IJ in the metropolitan region of Porto Alegre (the capital of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in Brazil) aged 13 (Elisa and Julia), 15 (Paulo), and 17 (Mateus) years old, two of them with single-parent families (Elisa and Mateus), one with a reconstituted family (Julia), and one with a vast family (Paulo). They were under treatment at CAPS IJ for three months (Elisa), six months (Paulo), ten months (Julia), and 11 months (Mateus). It is noteworthy that, of the four participants, only Elisa was not attending school at the time the interviews were being conducted, and Paulo had already dropped out six months beforehand. The names used are fictitious to preserve the participants' identity.

The criteria for the selection of the participants were: being over 12 and under 18 years of age, according to the definition of adolescence by the Statute of the Child and Adolescent (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente, in Portuguese - ECA, 1990); having had at least one episode of intentional self-harm behavior, with or without suicidal intention; having been treated in CAPS IJ for at least a month. Were excluded from the research adolescents who had no indication from the technical team to participate in the study; as well as teenagers who did not accept to participate or did not have authorization from their legal guardian to participate in the research. After analyzing the indications of the technical team, four cases of different sexes, different ages, and different family configurations were selected by convenience, seeking diversification of characteristics in the sample.

Instruments

• Interviews with the adolescents: a semi-structured interview was used to investigate the following aspects: self-injurious behavior ("What do you use to self-injure? What do you normally feel before you start self-injuring?"), teenagers' perceptions of their families ("Who do you live with and how is your relationship with these people? Which person in your family do you feel the safest to talk to when you have a problem?"), internet access ("Have you ever used the internet to search for contents related to self-harm?"), peer influence ("Before hurting yourself for the first time, had you seen it being done by someone else in another occasion?"), the school's role in self-harm behavior ("Can you talk about positive and negative situations you have already experienced at school? Which people from school usually help you when you have a problem?"), perception about mental health treatment ("Do you notice any difference in how you were feeling when you first arrived at this service and now? What kind of help do you receive?"), and future perspectives ("What things would you like to change or keep in yourself or in your life? How do you imagine yourself in the future?").

• Medical Records: were used to collect socio-demographic data from the adolescents, such as age and education, and data on the original family (mental disorder, configuration, home residents), their behavior and the history of assistance at the institution (psychiatric evaluation, medications, previous hospitalizations, other service treatments).

• Five Field Map: ludic instrument adapted for Brazil by Hoppe (1998) to assess the structure and function of the social supportive network. The Five Field Map consists of a felt cloth with six concentric circles divided into areas and figures that can be affixed using velcro. The figures represent adults, adolescents and children and should be arranged by the participant according to the level of proximity and the category in which that person fits: family, CAPS IJ, friends and relatives, formal contacts, and school. In this study, the Five Field Map was used as a complement to the interview, seeking more data on the quality and quantity of the bonds of each participant's supportive network.

Procedures and ethical considerations

During the procedure, 139 medical records were identified. They belonged to active and inactive patients in the service with a history of self-injurious behavior and were analyzed in a previous quantitative study. With this sample, CAPS IJ professionals were asked to identify adolescents attending the service at the time of the research and who fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this study. The institution authorized the research, and the professionals identified seven adolescents. Five of them were contacted, and four accepted to participate in the research.

The study followed guidelines for research with human beings, according to the Resolution No. 510 of the National Health Council (Brasil, 2016) and to the articles set by Statute of the Child and Adolescent (ECA, 1990). To this end, the research project was submitted to the university's Research Ethics Committee, approved under opinion No. 3.202.582.

The guardians who agreed with the adolescent's participation in this study signed a Free and Informed Consent Form and the respective adolescent an Informed Consent Form. Two meetings were held with each participant; the first for the interview and the second for the application of the Five Field Map, with an average length of 40 and 35 minutes, respectively. The meetings were previously scheduled, according to the availability of adolescents and were held individually in a private room within the institution. The interviews were recorded, fully transcribed, and later analyzed.

Data Analysis

After being transcribed, the interviews were submitted to content analysis. As suggested by Bardin (2011), the analysis followed three main steps. In the first stage, the pre-analysis, the reading of the transcripts was carried out, as well as the organization of the interview data and the Five Field Map. After that, in the stage of material exploration, the coding, classification and categorization systems of the collected material were defined, according to the registration units. This definition was based on the four dimensions of the PPCT model - process, person, context, and time (Bronfenbrenner, 2011). Finally, in the stage of treatment of results, the data, which had been previously defined, were also discussed in three main axes that grouped the dimensions of the PPCT model: (1) Characteristics of self-injurious behavior (person); (2) Family characteristics and perceived supportive network (context and proximal processes); and (3) Prospects for the future (time), based on the available literature concerning self-injury, the Bioecological Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2011) and Nock's (2009) integrative theoretical model. The organization of the results in the PPCT model and the posterior discussion of these in the axes of analysis were carried out based on common consensus among the researchers, seeking to observe both protective and risky characteristics present in the cases.

The Five Field Map was applied to three of the participating adolescents because one of them did not attend the second meeting scheduled. For this study, the five fields were named: family, CAPS IJ, friends, formal contacts, and school. Written records of the application were made according to the instrument protocol, and there was also an audio record. The data of this instrument were analyzed qualitatively, observing the number of people in the fields and the level of proximity perceived by the adolescents. Such data were reported in the "process" and "context" dimensions in the results section and posteriorly discussed together with the rest of the data from interviews in the three axes of analysis. Finally, the data triangulation process was carried out (Yin, 2005) based on the participants' medical records, the interviews and the results of the Five Field Map, aiming at a greater validity of this research.

Results

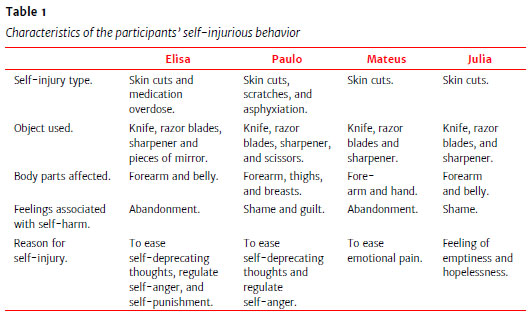

The results of the data analysis of the four participants in the study are presented together, describing the adolescents' personal and self-injurious characteristics in the Person category; characteristics of their relationships and proximal processes in the Processes category; characteristics of the contexts to which they belong, with emphasis on family, school, friends, and the internet, in the Contexts category; and aspects of their past, present, and future in the Time category. After the presentation of the main results, a table (Table 1) is presented and it exemplifies, with participants' lines, the categories of the PPCT model and the respective axes of analysis regarding the discussion.

Person

Elisa, Paulo, Mateus, and Julia are teenagers who arrived at the service due to self-injurious behaviors. All adolescents went through a psychiatric evaluation and were using medications, both of the girls had recently gone through a short period of psychiatric hospitalization. As stated in the individual medical records, only Elisa did not have a psychiatric diagnostic hypothesis, while the others had diagnostic hypotheses of Bipolar Mood Disorder and Major Depressive Episode. Mateus and Julia reported being heterosexual, while Elisa said she was bisexual, and Paulo presented himself as a transgender, homosexual boy. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants' self-injurious behavior.

The episodes of self-injuries started about two years ago for Elisa and Paulo and a year ago for Mateus and Julia. The time between the beginning of the self-harm behavior and the moment they arrived for mental health treatment was, on average, 9.5 months - the shortest time being from Julia (3 months) and the longest from Elisa (1 and a half years).

When asked about the criteria for choosing the body regions, they all affirmed having two basic criteria, being 1) the ease for hiding the injuries and 2) the sensitivity to pain in the region. The adolescents reported that self-harm started superficially and with long periods of separation between the episodes. They started as a "training" in Mateus' case, progressively increased their frequency (reaching twice a day) in Julia's case, and sometimes reached a severity point (requiring medical care). All adolescents performed self-harm behavior at home, preferably in the bedroom or bathroom.

There were disagreements about the beginning of the self-injury episodes since Paulo and Julia thought about self-harm for a few months before starting to perform this behavior, and Mateus and Elisa did it impulsively, without prior planning. The four adolescents also reported social isolation (not going to school, missing family meetings, staying in the bedroom for long periods), either because they intended to hide the injuries or because they thought they would not be understood.

Self-harm came from intense sadness and, later, generated psychological relief for all four adolescents. Regarding possible intentions to suicide, all adolescents answered that these types of thoughts varied over time, having appeared in some self-harm episodes but not in all of them. Even when these thoughts were there, feelings related to death were always ambivalent since the adolescents stated that, after having started the suicide attempts, they gave up in the middle of the process of injuring themselves and/or sought help afterward.

The suicide ideation also varied according to the type of method used. For Paulo, the time he tried to choke himself was when his intention to suicide was the clearest ever. Likewise, Elisa took a toxic amount of medication when she intended to commit suicide. These adolescents do not know how to point out the difference between the suicide ideation of these episodes and the others, in which they used sharp objects, as they admitted having already tried to die in both cases. Above all, they affirm that, when using alternative methods - and, apparently, more lethal - the desire to die seemed clearer.

Process

The proximal processes identified in the participants worked as precipitating factors for self-harm and as protective factors against mental illness. The relationships with people in the most diverse systems influenced the way these adolescents connected to self-harm.

Family relationships were sometimes marked by violent experiences in psychological (Julia and Paulo), physical (Paulo), and sexual (Elisa) terms. For the adolescents, family relationships were invalidating (Paulo and Julia) and distant (Mateus). Although Mateus considers having a good relationship with his father, the teenager says the man has always been "a private person", and he does not remember ever seeing him sad or crying. On the other hand, Elisa feels like she has always had her privacy "invaded" and was repeatedly involved in the marital fights of her now-divorced parents. Paulo, however, says that, when his self-injuries were discovered, this issue was exposed at a family dinner, causing him immense embarrassment and disappointment. All the participants especially emphasize a feeling of invisibility: they consider that, in different ways, their identity, privacy, and emotions were denied by their families.

In contrast, in times of greater emotional vulnerability, the adolescents were able to count on other family members who offered them comfort and a safe environment in difficult times. Julia and Elisa mention the maternal grandmothers as people of their trust and affection, while Paulo names his sister, being the only family member who supported him in his gender transition and encouraged him to search for his identity.

Risky and protective relationships were also highlighted in the school context. Julia and Elisa mention situations of bullying which they experienced in the past, while Paulo still has to deal with these situations. Regardless, it was also in this context that they found more support. Elisa reports, for example, that she felt supported by her Portuguese teacher when he surprised her by revealing personal difficulties that he had also gone through. On the other hand, Paulo reinforces that he distanced himself from everyone at school because he was convinced that no one would understand what he was experiencing.

The importance of friends was also present in the participants' reports. Many peers were the first people to know about their self-injuries, as in the case of Elisa and Mateus. For Elisa, even a friend, who had been undergoing psychological treatment, encouraged her to seek help at the CAPS IJ. She values this support and says it is a way to alleviate her loneliness. Furthermore, Mateus considers that only a few people his age can understand what a mental illness means: he realizes he has lost friendships because of his emotional difficulties.

On the other hand, friends were the main influences for engaging in this type of behavior since all participants had previously met a classmate or close friend who had practiced self-harm or committed suicide. Julia says she remembers a classmate who always showed up with many cut marks on her fists. Although she did not understand it at the time, when she began to consider self-harming, she remembered the girl and immediately thought that if it worked with her friend, it could work with her too. Mateus had a classmate who committed suicide, and he mourns, with great sadness, that the girl did not receive help in time.

The Five Field Map made it possible to observe the distribution, in different contexts, of the relationships mentioned by the adolescents and to qualify them according to their proximity or distance. The systems were named "family", "relatives", "friends", "school" and, the last one, "formal contacts", which included services such as CAPS IJ, church, music groups, and sports groups.

For Julia, people of her extended family were the only ones who occupied level 1 (closest proximity) in her map, while people of her nuclear family occupied the 3rd and 4th levels, being her father mentioned as a broken relationship. In the category of "formal contacts", Julia mentioned her CAPS IJ reference technician, who assists her systematically, and to whom she says she shares a relationship of trust and reciprocity. In the categories of school and friends, Julia represented close and numerous relationships. Her maternal aunt was identified as the person who helps her in critical moments.

For Mateus, level 1 was occupied by all contexts and the teenager reported a positive perception of the supportive network. In the context of friends, he included virtual and childhood ones. The conflictual relationships included his ex-girlfriend and a friend he had at the time he was ill, mentioned as "not good company". Although he had previously spoken about his father being a private person, he placed him at the first level of the family context and pointed him out as the person who helps him the most in times of need.

In Paulo's case, the "relatives" category was most represented in level 1, with five people. In contrast, the adolescent placed the "family" section in levels 4 and 5, mentioning his broken relationship with both mother and father. Friends were represented as close to Paulo on the map, but his sister was perceived as the main source of support.

Context

Although they consider the self-harm phenomenon to be solitary, the teenagers have always been included in contexts that seem to have directly or indirectly contributed to this conduct's functioning. Family, school, health services, and the internet were the main systems mentioned by the participants.

According to Paulo and Julia, even though the nuclear family was not protective in many moments, the extended family proved to be a satisfactory microsystem. They said they tend to feel more supported by relatives who do not live with them than by those with whom they share or have shared the same house. The four adolescents mentioned frequent disagreements in the family context that were often triggering episodes for self-injurious behavior. Although they consider it important to have a family, they do not always feel protected by them.

Regarding the school, except for Elisa, who was dropping out of school and perceived this place as hostile, and Paulo, who suffered situations of bullying, the other two participants spoke of this environment as a positive and "welcoming" place. In general, it is mentioned as an important space for socialization, for sharing experiences and stories, and for the supportive relationships that are established. Sometimes, however, the school reproduces competitive relationships with an imbalance of power, which directly affects students' mental health, as stated by the adolescents.

While family and friends represent the main microsystems in a teenager's life, the internet is probably one of the current protagonists of the mesosystem since it is in this space that many relationships are formed, as well as proximal processes. The participants named the internet a "parallel reality", where they can seek complementary information to their daily experiences, despite their opinion on the role of virtual reality being quite diverse. For Paulo, online information can worsen depressive symptoms and promote more self-destructive behaviors. On the other hand, Julia, Mateus and Elisa ponder the positive aspects of this method of communication: the possibility of expressing feelings that cannot be said on face-to-face situations, an expansion of the supportive network, guidance on where to seek help, information on self-care and on homemade care for self-injuries, and connection with similar stories.

In fact, it was through a virtual friend that Elisa learned about the existence of CAPS IJ in the municipality. For the other participants, the trajectory in the service occurred differently: Paulo had been transferred from a CAPS IJ in the municipality where he lived with his father, while Julia and Mateus were referred by the Municipal Emergency Service. Despite coming from different trajectories in the intersectoral service, the four adolescents agree on one aspect: CAPS IJ has become a space for personal restructuring. Paulo says that he found an outlet for all his emotions in the service. Likewise, Julia says that she found refuge at CAPS IJ at a time when her family did not even welcome her. Different from what she had imagined, she noticed that receiving a diagnosis of mental disorder was liberating and fundamental for validating her suffering. Because of that, Mateus and Elisa feel more secure and motivated to make new plans. They do not see CAPS IJ as a place of illness but a way to recover their health and potential. The health center of the participants' territory and the psychiatric hospitalization experienced by Elisa and Julia were also mentioned as spaces of care but with less proximity.

Time

The dimension of time can be assessed on various issues addressed by the adolescents during the interview. When referring to the past, the teenagers could not remember a previous moment when they felt emotionally healthy. Everyone spoke of their childhood as a period of intense difficulties, such as Paulo's episodes of psychological violence and parental disregard experienced by Julia. Julia even says that she could not register her father's name in her documentation because her mother did not want them to have any sort of contact. Thus, it was shown that emotional vulnerability has always accompanied these adolescents throughout their development and was only aggravated by stressful events. As for the macro-time, transgenerational aspects were also observed in the participants' stories, as in Elisa's case, who mentioned having witnessed an episode of self-injury by her older sister and the history of mental disorders in Mateus's nuclear family (mother and brother).

The participants noticed changes that had been occurring over the years, some gradually and others abruptly, such as the loss of close family members in Mateus' and Julia's cases. They also talked about skills they used to have but now are lost, as in Julia's case, who has recently been having school difficulties, but considered herself to be a great student in the past.

In the case of Paulo, however, these transformations were more intense: three years ago, he started a gender transition when he realized he no longer recognized himself, nor was he comfortable in a woman's body. It was a process that lasted for six months, as Paulo acknowledges that it took him a long time to accept there was nothing wrong with him. It was a change for himself and others: his family and classmates also found it difficult to adapt to his new name and appearance. Paulo stated that some of his self-injurious episodes were related to this transitioning process, but not because he rejected his new identity: his suffering was due to not being seen by others as he would like to.

When asked about what they would like to remain the same in their lives, adolescents responded that they would want to maintain their potential skills, such as sense of humor, mentioned by Mateus, and the dedication to school, mentioned by Paulo. In addition, they brought up the desire to continue seeking personal welfare and to keep intact some of their happy memories from their childhoods.

The four adolescents expressed a positive perspective for the future, with expectations of professional achievements, emotional maturity and a satisfactory mental health. They discussed about the wish to have a family of their own, through which they can establish healthier and stronger relationships. Above all, they want to have a future, and they know that even when they cannot see it, it does not mean that it does not exist, but that they just cannot perceive it at the moment.

Table 2 presents some of the participants' statements that were analyzed within the four categories of the PPCT model and the three axes of analysis used in the discussion. The verbalizations were selected to exemplify the characteristics of protection and risk observed in the categories.

Discussion

Characteristics of self-injurious behavior (person)

This study analyzed the characteristics of the supportive network and the self-injurious behavior of adolescents who were assisted by CAPS IJ service in the metropolitan region of Porto Alegre. Regarding the characteristics identified in the self-injury behavior, all four adolescents in this study used at least one and at most three methods of self-harm, with multiple episodes, and it took them, on average, nine and a half months to get to a health service. These data show behavior with severe clinical indicators due to the variability of methods used and the frequency with which they occurred (Ammerman et al., 2019).

Regarding the main functions assumed by self-injuries, the emotional regulation and self-punishment stand out, as reported by the participants. Emotional regulation can be observed when self-injurious behavior is used to alleviate intense and negative states of cognition and emotion and incite positive emotions, such as relief (Fonseca et al., 2018). On the other hand, self-punishment appears to be more connected to a self-deprecating and self-critical state (Nock, 2009). Although stressful environmental events have been identified and seem to have precipitated the beginning of this behavior, the participants also reported internal emotional states, such as loneliness, shame, guilt, and helplessness, that motivated the desire for self-harm.

In this scenario, the feeling of loneliness was an interpersonal vulnerability mentioned by all participants. The literature review executed by Calati et al. (2019) pointed out social isolation as one of the main factors associated with suicidal behavior in adolescence, being defined not only by the number of relationships, but by the frequency and quality they have. Consequently, loneliness was the feeling that accompanied the adolescents during the episodes, since they reported significant isolation and a sense of maladjustment to the environments around them.

The bioecological theory proposes that the biopsychosocial characteristics of an individual can assist in healthy development but also harmfully interfere in their full psychological growth (Bronfenbrenner, 2011). Likewise, in the model proposed by Nock (2009), individual variables seem to offer a greater risk for self-injurious behavior. Among the characteristics shown by the participants, the experience of highly aversive thoughts and emotions (self-hatred, guilt, shame, self-criticism, emptiness, hopelessness) stood out, as well as aspects of sexuality (in Paulo's case). However, for such personal characteristics to act in a significant way, it is necessary to consider the relational aspects of the person in context, over time, and to understand that these dimensions are not a summation but a complex interaction.

Family characteristics and perceived supportive network (context and proximal processes)

The participants frequently mentioned traumatic experiences in family relationships. Of all four participants, three of them reported physical, psychological, and sexual abuse suffered within the nuclear family, even though they did not link such experiences to their self-harm behavior. Regarding this, the literature points out that self-injury can possibly mean a maladaptive attempt to manage emotions, and it may be learned in violent contexts of childhood (Peh et al., 2017). In addition, the results also demonstrated the adolescents' dissatisfaction with the way their families handle their emotions, as they often felt invisible, discouraged, and invaded - which made evident the aspects of an invalidating environment.

Thus, if the characteristics of the developing person are the product and process of their social relationships, proximal processes will help determine the way the adolescent will be in the world (Bronfenbrenner, 2011). In this case, when the nuclear family is unable to establish reciprocal, constant, and regular interrelationships with the adolescents, the extended family, a constituent part of the mesosystem, can act in order to soften and reframe these relationships. The field "relatives" was the one with the greatest representation of people in the participants' supportive network and seemed to present a greater level of proximity compared to the family category, indicating that this is a microsystem with protective and encouraging relationships.

The peer group also proved to be a context marked by both positive and negative relationships. In the interviews with the participants of this study, peers were mentioned both as self-injury promoters and as a source of support and encouragement to seek help. Contagious behavior is reported in the study made by Giletta et al. (2015), which indicates the multiplier role played by the relationship among peers. This evidence was also identified in the data of this study, since all participants knew a close friend or relative who had previously self-harmed themselves or attempted suicide.

Since adolescence is a period in which the individual seeks a differentiation from the family group and, at the same time, a greater appreciation of the friends' network, there is evidence that conflicts with friends in addition to family abandonment can increase the chances of self-injurious behaviors (Giletta et al., 2015). Bullying is one of the phenomena that literature has pointed out as a precipitating factor of self-injurious episodes, increasing anxiety and depressive symptoms (Fisher et al., 2012). Still, friends can act to support and protect each other, preventing new episodes of self-harm and encouraging the search for help (Briggs et al., 2017). In this study, the "friends" field was the one that showed the greatest proximity factor in the Five Field Map among the participants. In addition, a positive sense was attributed to friendships regarding self-harm since adolescents sought support among peers and were given incentives from them to seek help.

In addition to friendships with face-to-face interaction, participants also mentioned the presence of friends in the virtual environment. Nevertheless, there were some disagreements regarding the support given by the network formed on the internet, insofar as some received support and accessed positive information for their self-care, and others reported an arousing of more negative emotions and self-destructive behaviors in this environment. Such ambivalence is also found in literature, as the internet can be seen not only as a tool to normalize self-injurious behavior and disseminate new forms of self-harm but also as an instrument for greater emotional expression, reduction of social isolation, and an incentive to the search for professional help (Briggs et al., 2017).

Finally, it can be assumed that the mental health service may have acted as a protective factor in the trajectory of the participants of this research since no negative aspects about this institution were identified in their reports (see Table 1). All of them saw the mental health service as a positive place and a promoter of care, even though the adolescents did not attribute a high degree of proximity to the professionals of this field in the Five Field Map. According to Bronfenbrenner (2011), the inclusion of the adolescent in a new context allows the movement of ecological transitions. These movements make it possible for the adolescent to expand their mesosystem, and this new environment also results in the modification of their social and affective supportive network, in addition to new experiences and new possibilities of roles they can perform. (Bronfenbrenner, 2011). In this sense, CAPS IJ appears as a new source of support, allowing the participants to have a moment of family and personal reorganization and offering them a new meaning to their experiences.

Prospects for the future (time)

The changes identified in the participants' histories were significant. The concept of chronosystem proposed by Bronfenbrenner (2011) highlights the temporal dimension in which an individual is inserted, considering the historical factors that either change or remain the same throughout their development. In terms of macro-time, mental illness in the family setting can be considered, as identified in the history of some participants, and indicates the transgenerationality of emotional problems throughout the family cycle. Other studies on self-injury have already considered that having family members with a previous mental disorder can constitute a relevant risk factor for the adolescent's susceptibility to self-injurious behavior (Simioni et al., 2018; Tschan et al., 2015). In addition, despite being an old behavior, self-injury has been taking the lead among young people over the last few years, being characterized as a current phenomenon with a socio-cultural aspect (Favazza, 2009). The author points out that this behavior is, above all, a contemporary form of risky behavior and externalization of emotional pain.

Stressful events were also identified in the history of adolescents, besides having a particular impact on their process of mental illness. Family conflicts, the loss of family members, and gender change were some of the issues mentioned by the participants. All these changes involve a cumulative meaning to the adolescents' experiences (Bronfenbrenner, 2011), culminating in dysfunctional regulatory strategies, such as self-injury.

As for the future, it was observed that the positive desire for the future was still preserved by the adolescents who participated in this research. Although emotional vulnerabilities have been observed in the personal dimension, time appears as a way to reconfigure the dynamics of established proximal processes. Plus, it enables a new repertoire of management skills to life events and to interactions in the environment (Leme et al., 2016).

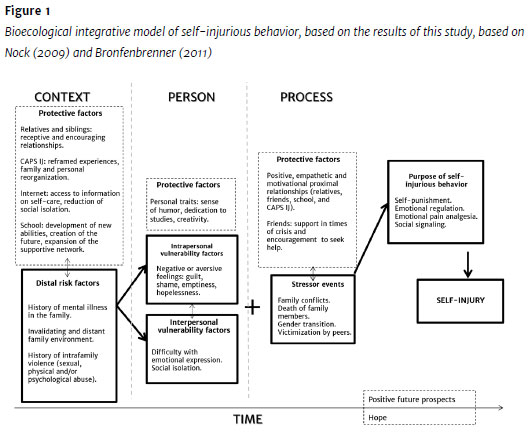

Based on the results of this study, a model was organized (Figure 1), taking into account aspects of the Bioecological Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2011) and the integrative model of Nock (2009). In this model, some protective factors identified in different contexts were highlighted, as well as the main risk factors found in the adolescents' histories, which seem to have contributed to their self-injurious processes.

Considering the relationship among all the identified factors, one begins to understand the regulation of affective experiences and the social situations experienced by adolescents and how these variables can be related to self-injurious behavior. The model organized from the information collected suggests the importance of a contextualized approach, considering the adolescents' characteristics, the contexts in which they are inserted, and the changes and processes that happened over time. These results can contribute to research and interventions with adolescents in the school and the family context.

The bioecological model allows the investigation of phenomena based on an interactionist and integral logic of human development. Thus, it was possible to assess the individual aspects of the interviewed adolescents concerning their supportive networks in the most different systems and over a continuum. The main distal risk factors for their development were the history of family mental illness, past intrafamily violence, and an invalidating family environment. Feelings of guilt, shame, hopelessness, and emptiness were observed as intrapersonal risk factors, while social isolation and difficulty with emotional expression were identified as factors of interpersonal vulnerability. The main stressors that precipitated self-harm were peer victimization, family conflicts, gender transition, and death of family members.

On the other hand, it was possible to observe protective factors in their individual stories, such as positive relationships with relatives and schoolmates, which provide them with support and encouragement; personal characteristics of creativity, sense of humor and dedication to studies; virtual friends, who contribute to reducing the feeling of isolation; the health service, which contributes to the adolescents' family and personal reorganization and offers a new meaning to their experiences; and also the positive plans for the future, which provide a feeling of hope. Thus, the combination of all protective factors identified helps developing a repertoire of management skills for life events and interactions with the environment, which, to some extent, can alleviate the negative effect of risk factors.

However, some limitations of this study can be highlighted. The design of this research did not allow a more in-depth analysis of the effect of protective factors on the self-harm process, nor an exploration of how it contributes to soften the risks that lead to self-injury. In addition, the lack of interviews with family members and the lack of information about school records prevented a more detailed assessment of proximal processes. Still, considering that the research was carried out in a CAPS context, with adolescents undergoing psychological counseling, there may be a sampling bias, considering the presence of more serious self-injurious behaviors in the service than in the general population. Consequently, these behaviors could be more associated with mental disorders. As for the model represented from the data of this study, it is understandable that it is necessary to validate quantitatively and qualitatively the interactions between risk and protective factors, seeking greater comprehension not only about the causal factors of this phenomenon, but also about the mediating and moderating ones.

It is suggested that further studies investigate the cultural aspects of self-injury since it is often characterized as a current phenomenon. New studies may contribute to reaching an explanatory model that assesses the mediating and moderating role of protective factors in self-injurious conduct, making it more integrative, besides subsidizing interventions for self-injurious prevention. These types of research must be in constant development so that structured public policies strengthen the national health service (SUS) and efforts to prevent suicide are increased. It is necessary to investigate how adolescents are seen and inserted in social contexts and how their role has been encouraged or mitigated. It is believed that the strengthening of bonds in adolescence between family members, community members, or peers can be a possible way to lessen emotional distress, reduce risky behaviors and increase the chances of coping with stress.

References

Ammerman, B. A., Jacobucci, R., Turner, B. J., Dixon-Gordon, K. L., & McCloskey, M. S. (2019). Quantifying the importance of lifetime frequency versus number of methods in conceptualizing nonsuicidal self-injury severity. Psychology of Violence, 10(4),442-451. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/vio0000263 [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de conteúdo. Edições 70. [ Links ]

Brasil. (1990, Julho 13). Lei nº 8.069. Dispõe sobre o Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente e dá outras providências. Presidência da República. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8069.htm [ Links ]

Brasil (2016, abril 07). Resolução n. 510. Ética na Pesquisa na área de Ciências Humanas e Sociais. CNS [ Links ]

Briggs, S., Slater, T., & Bowley, J. (2017). Practitioners' experiences of adolescent suicidal behaviour in peer groups. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(5),293-301. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12388 [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2011). Bioecologia do desenvolvimento humano: tornando os seres humanos mais humanos (Carvalho-Barreto, A., trad.). Artmed. [ Links ]

Calati, R., Ferrari, C., Brittner, M., Oasi, O., Olié, E., Carvalho, A. F., & Courtet, P. (2019). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245,653-667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.022 [ Links ]

Crowell, S. E., Baucom, B. R., McCauley, E., Potapova, N. V., Fitelson, M., Barth, H., Smith, C. J., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2013). Mechanisms of contextual risk for adolescent self-injury: Invalidation and conflict escalation in mother-child interactions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(4),467-480. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.785360 [ Links ]

Favazza, A. R. (2009). A cultural understanding of nonsuicidal self-injury. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 19-35). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11875-002 [ Links ]

Fisher, H. L., Moffitt, T. E., Houts, R. M., Belsky, D. W., Arseneault, L., & Caspi, A. (2012). Bullying victimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ, 344,e2683. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e2683 [ Links ]

Fonseca, P. H. N. D., Silva, A. C., Araújo, L. M. C. D., & Botti, N. C. L. (2018). Autolesão sem intenção suicida entre adolescentes. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 70(3),246-258. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1809-52672018000300017 [ Links ]

Giletta, M., Prinstein, M. J., Abela, J. R., Gibb, B. E., Barrocas, A. L., & Hankin, B. L. (2015). Trajectories of suicide ideation and nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents in mainland China: Peer predictors, joint development, and risk for suicide attempts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(2),265-279. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038652 [ Links ]

Hoppe, M. (1998). Redes de apoio social e afetivo de crianças em situação de risco. [Unpublished Master's dissertation]. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, RS. [ Links ]

Leme, V. B. R., Del Prette, Z. A. P., Koller S. H., & Del Prette, A. (2016). Habilidades sociais e o modelo bioecológico do desenvolvimento humano: Análise e perspectivas. Psicologia & Sociedade, 28(1),181-193. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-03102015aop001 [ Links ]

Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2),78-83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x [ Links ]

Peh, C. X., Shahwan, S., Fauziana, R., Mahesh, M. V., Sambasivam, R., Zhang, Y., Ong, S. H., Chong, S. A., & Subramaniam, M. (2017). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking child maltreatment exposure and self-harm behaviors in adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67,383-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.013 [ Links ]

Simioni, A. R., Pan, P. M., Gadelha, A., Manfro, G. G., Mari, J. J., Miguel, E. C., Rohde, L. A., & Salum, G. A. (2018). Prevalence, clinical correlates and maternal psychopathology of deliberate self-harm in children and early adolescents: Results from a large community study. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 40(1),48-55. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2016-2124 [ Links ]

Tomé, G., Camacho, I., Matos, M. G., & Simões, C. (2015). Influência da família e amigos no bem-estar e comportamentos de risco: Modelo explicativo. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 16 (1),23-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.15309/15psd160104 [ Links ]

Tschan, T., Schmid, M., & In-Albon, T. (2015). Parenting behavior in families of female adolescents with nonsuicidal self-injury in comparison to a clinical and a nonclinical control group. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1),17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0051-x [ Links ]

Turecki, G., & Brent, D. A. (2016). Suicide and suicidal behaviour. The Lancet, 387(10024),1227-1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2 [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2005). Estudo de caso: Planejamento e métodos. Bookman. [ Links ]

Zappe, J. G., & Dell'Aglio, D. D. (2016). Variáveis pessoais e contextuais associadas a comportamentos de risco em adolescentes. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 65(1),44-52. https://doi.org/10.1590/0047-2085000000102 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Manuela Almeida da Silva Santo

Rua Ramiro Barcelos, n. 2600, Santa Cecília

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. CEP 90035-003

E-mail: manuelassanto@gmail.com

Received: April 21st, 2020

Accepted: March 19th, 2021

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI