Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Universitas Psychologica

versão impressa ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.9 no.2 Bogotá ago. 2009

Paz y guerra como representaciones sociales: una exploración con adolescentes italianos*

Peace and war as social representations: a structural exploration with Italian adolescents

Mauro Sarrica**; Joao Wachelke

University of Padua, Italy

ABSTRACT

The present paper illustrates the potentialities offered by the Social Representations approach to the exploration of peace and war concepts. Free associations tasks to the stimuli War and Peace were given to 112 students in order to assess contents and structures. Differences related to gender, age and school grade were investigated. Attention was devoted to the role of peace education activities. Results indicate a dramatic representation of war, based on death and destruction. The representation of peace is based on intimate and positive emotional experiences. It appears weaker and polyphasic, with cues of change. Respondents involved in peace education show greater complexity of contents and more features related to positive approaches to peace, thus underlining the relevance of these activities.

Keywords authors: Peace psychology, Social representations, Peace education.

Keywords plus: Social Representations, Peace education, War and society.

RESUMEN

Este artículo ilustra las potencialidades ofrecidas por la aproximación de las representaciones sociales, para la exploración de los conceptos de paz y guerra. Se administraron tareas de asociación libre con los estímulos guerra y paz a 112 estudiantes, para evaluar sus contenidos y estructuras. Se investigaron diferencias relacionadas con el sexo, la edad y la escolaridad. Se prestó atención al papel de las actividades de educación para la paz. Los resultados indican una representación dramática de la guerra, basada en la muerte y la destrucción. La representación de la paz está basada en experiencias emocionales íntimas y positivas; parece más débil y polifásica, con claves de cambio. Los respondientes involucrados en Educación para la Paz, mostraron más complejidad conceptual y más características relacionadas con aproximaciones positivas a la paz, enfatizando la relevancia de estas actividades.

Palabras clave autores: Psicología de la paz, Representaciones sociales, Educación para la paz.

Palabras clave descriptores: Representaciones sociales, Educación para la paz, Guerra y sociedad.

I just want you to know that,

when we talk about war,

were really talking about peace.

George W. Bush, June, 18 20021

Peace and war are multifaceted and elusive concepts, and their definition animates discussions in social sciences (cf., Anderson, 2004). The present work is placed within the wider perspective of peace psychology, a field that is cross-sectional to psychology, which proposes a critical approach directed towards the development of research and interventions aiming at facing both direct and structural violence (Christie, Wagner & Winter, 2001). This framework is rooted in the distinction made by Galtung between a negative and positive conception of peace (Galtung, 1996; Galtung & Tschudi, 2001): the former sees peace as an absence of war and accounts for a passive and static view of it, while the latter conceives peace as a set of activities directed towards the construction of civil cohabitation that structurally excludes violence, but not the emergence of conflicts. Adopting a bottom-up perspective, the current work presents an exploratory study aimed at characterizing the social representations of peace and war shared by secondary school students from Venice, Italy. Special attention has been given to the differences between students who had taken part in peace education activities and those who had not. Here we refer to peace education following the broad definition by Harris: “ teachers teaching about peace: what it is, why it does not exist and how to achieve it. This includes teaching about the challenges of achieving peace, developing non-violent skills and promoting peaceful attitudes” (Harris, 2004, p. 6).

Before addressing the presentation of the study, we will review briefly the main results obtained on the development of peace and war concepts and about the heuristic possibilities provided by the social representations approach to this investigation context.

Peace and War according to Developmental Perspectives

Within peace psychology, the education to peace and the promotion of a peace culture in children and adolescents have received special attention both for purely applied interests and theoretical and research purposes (cf., Harris, 2004¸ Vriens, 1999). The capacities to understand and form peace and war concepts have been studied from the 60s (cf., Hakvoort & Oppenheimer, 1998); until the 70s, research was carried out mostly in Western Europe and in the United States (e.g., Ålvic, 1968; Cooper, 1965); from the 80s on, studies have been extended to Eastern European countries, Israel and Australia (Hakvoort & Oppenheimer, 1993; Raviv, Oppenheimer & Bar-Tal, 1999).

Research lines often relate to themes linked to the political agenda. In the 80s, special attention has been dedicated to the fear of nuclear war (Mack & Snow, 1986; Ponzo & Tanucci, 1992), the 90s were distinguished by a relative lack of interest, and more recently attention is turned to the topic of terrorism (e.g. Burnham, 2007).

Concerning the cognitive representations of peace and war, two perspectives have characterized the research field. The first one is linked to genetic epistemology and underlines the relationship between individual development and conceptual complexity; the second focuses on the contents acquired from the context in the course of primary and secondary socialization.

Studies on cognitive and socio-cognitive development (cf., Hakvoort & Oppenheimer, 1998) agree at the existence of a fairly elaborate understanding of the concept of war in children as young as six years of age. This is initially linked to concrete objects and actions (weapons, shooting) and is gradually integrated to the consciousness of reciprocal damage and related suffering. The concept of peace appears to come later and in a more complex way: until the age of twelve it is possible to observe a growing use of the concept of negative peace, that is, the absence of war at a macro level and of conflicts at an interpersonal level, accompanied by the presence of positive social feelings (e. g., being kind). In the years before adolescence, a positive conception of peace based on cooperation and reciprocal understanding is formed. However, “the understanding of peace becomes more varied and complex as children are older, but simultaneously refers to (early childhood) issues such as disarmament, attention to nature and pollution, and sharing” (Hakvoort & Oppenheimer, 1998, p. 382). Some studies (cf., Hakvoort & Oppenheimer, 1999) demonstrate gender differences: girls are more prone to conceive peace at an interpersonal level –micro level– and to focus on the consequences of war; boys, on the other hand, describe peace in terms of disarming of nations (macro level) and concentrate mostly on war objects-guns, airplanes.

Studies directed towards socialization and changes in social enviroment (e.g. Spielman, 1986) are less frequent. Even though they agree at stressing the roles performed by the cultural context (often operationalized as national belonging) and by social institutions and groups (family and school), such studies do not seem to be comparable. As a consequence, it is difficult to outline precisely the role taken by the various studied components (such as norms, culture, values). As an example of the long term effects of World War II, Dinklage and Ziller (1989) showed differences on the representations of war shared by German and American children: the former referred to destructive aspects and the perception of personal threat more than did the latter. In contrast, Hakvoort & Hägglund (2001), next to shared themes such as absence of war, absence of conflicts and social activities, stressed differences between the concepts of peace elaborated by Swedish and Danish children and adolescents. Danish participants, brought up in a country that was directly involved in World War II, tended to make references to interpersonal attitudes (tolerance, equality, solidarity) whereas the Swedish participants adopted more distant perspective, linking peace to international collaboration. Concerning more recent contextual changes, research carried out by McLernon and Cairns (2006) demonstrated that political changes that took place in North Ireland between 1994 and 2002 –following the 1994 cease fire– influenced the ideas that adolescents have on peace and war.

Regarding Italy, results are compatible with the ones that were presented in international literature (Sbandi, 1988; Bombi, Cristante & Talevi, 1983). Sbandi (1988) underlined the increase that comes with age in the capacity of taking more general aspects of war into account – from war as confrontation of powerful leaders to an image that includes the conflict between nations and peoples. Gender differences were also shown: boys tended to refer to an international level, while girls focused at an intrapersonal one. It is important to notice that, like German youngsters, Italian youth associated war with destruction. In a similar way, Pagnin (1992) identified four main phases marked by a different capacity of coordinating the relationships among intentions, means and ends in a complex way. According to this model, the concept of war reaches bigger strength and evocative capacity at a younger age. Peace, instead, remains weaker and undefined, described through “stereotypy –drawings of ring-a-ring-a-roses and flowers–, or with aspects of a negative nature- ending war, doing peace –and still as a feeling– to be well together, to like each other“ (Pagnin, 1992, p. 216). Again, higher complexity is observed only with the coming of adolescence.

Peace and War as Social Representations

A smaller number of studies on peace and war were directed towards young people and adults (Pecjak, 2003; Rodríguez, 2005) and even less have followed a socio-constructivist approach. In that direction, the theoretical perspective of Social Representations (Moscovici, 1961/1976) looks particularly interesting because it aims at “collecting that which we know from the context of our experience and contemporary culture” (Moscovici, 1992, p. 140), allowing to switch the focus of study from cognitive capacities to the representations of peace and war as a “socially elaborated and shared form of knowledge that has a practical goal and builds a reality that is common to a social set” (Jodelet, 1989, p. 48).

According to a structural perspective, a representation is a structured set of base-ideas, the cognems, which refers to a social object, i.e. to a theme of social life that is relevant to the group (Abric, 1994a); both the elements and their relationships find their legitimacy within the same social group (Flament & Rouquette, 2003).

Empirical studies demonstrate that a few elements organize the representation, define its identity and evaluate the main situations related to it. Those elements are more stable and consensual than others, and they form a structural subset that is called central core (Abric, 1984; Lheureux, Rateau & Guimelli, 2008; Moliner, 1989). The remaining objects are less widely shared and more flexible. They are related to practical aspects, forming a peripheral system that aims at adapting the representation to specific contexts. By acting this way, peripheral elements preserve the central core when it is faced with conflicting information, and at the same time makes it possible to integrate new information to the structure (Flament, 1989, 1994; Rouquette & Guimelli, 1995).

A few studies have been conducted on the structures of social representations of peace and war, stressing the role of context in favoring the emergence of different representations. For example, Wagner, Valencia and Elejabarrieta (1996) compared Nicaraguan and Spanish participants, finding out that peace has scarce salience in the European country, in contrast with the Latin American one. In the former, the context did not stimulate discussions on the topic, disallowing the formation a stable representation of peace. In Nicaragua, conversely, the end of civil war urged people to consider it in a more pressing way, favoring the elaboration of more stable meaning structures for both peace and war. It is important to point out that the meanings in both nations gather some elements of knowledge that had already been brought to light by evolutionary research, but their relationship changes, creating different representations.

Israeli, Palestinian and European adolescents have been compared in a similar way (Orr, Sagi & Bar-On, 2000). Among Middle-eastern youth it was possible to observe a representational field in which individual and ethno-national values –e.g. Palestinian independence– were linked. Both Palestinian and Israeli participants shared a representation that tends to justify war and that excludes peace from the relevant values. Just as a kind of dysfunctional collective coping strategy, adolescents adapted to an unsolvable conflict convincing themselves that their reality was the only possible one.

Particularly, for activist adolescents, war was less legitimate and peace less weak. Moreover, while non-activists tended to converge toward more elementary representational aspects –loyalty, general rejection of war–, the activists presented a more complex representation, able to include abstract components but also references to normative dimensions and behavior linked to the individual sphere.

More recently, in 2001, adults involved with peacemaking organizations showed a better structured and more active representation of peace than a more changing and unrealistic one shared by non-activists (Sarrica & Contarello, 2004). During 2004 and 2005, a few transformations of the representations were identified. Even on the representations of people not directly involved in movements for peace, there was an emergence of references related to positive peace –cooperation, solidarity-next to aspects that are symbolic– white doves, blue skies –and introspective– silence of the senses (Sarrica, 2007). The social representation of war remained stable and structured around the concept of death.

At a theoretical level, the research about social representations of peace and war are linked to two key theoretical aspects: the relationship between representations and practices and the relationships among different social representations. As we have seen, social representation and practices are mutually inter-related. Some authors state that determination can occur in both directions (Rouquette, 1998), while others defend that behaviors are one representation component, and that it is not possible to distinguish them (Wagner, 1994). Theoretical and empirical advances suggest that in case of practices that contradict or challenge established knowledge, practices can transform representations (Flament & Moliner, 1989; Guimelli, 1989) or bring to light the existence of implicit patterns –not necessarily mutually compatible (Wagner, Duveen, Verma & Themel, 2000).

The link among social representations is a more recent issue, and a few types of coordination relationships have been identified by research. Concerning peace and war, we may hypothesize that such objects are in a relationship of opposition. The antinomy relationship occurs when there is a coincidence of elements on the core of two social representations, and those elements take opposite characteristics (Guimelli & Rouquette, 2004). An example may be the negative conception of peace – absence of war, as observed on the representations shared by non-activists. However, such relationship does not seem to hold true always: war and peace proved to have different strength and different capacity to influence each other structures according to the context (Wagner et al., 1996); moreover, if we take into account practices, activists often seem to share representations that are not directly linked to war contents (Pagnin, 1992; Sarrica & Contarello, 2004).

Aims and expectations

The general aim of the present paper is to explore the issues of Peace and War as social constructions and to understand how practices related to peace education may reverberate on them. We will refer to the social representations framework to investigate: a) the shared contents elaborated by young people; b) differences related with gender, age and school year; c) the role that peace education activities play in fostering specific representations of Peace and War. Following the examined literature, it is suggested that:

• a highly shared and concrete social representation of War should emerge; we expect it to be structured around the themes of destruction and death;

• the social representation of Peace may include more symbolic contents but, as shown in recent Italian studies, other contents related to positive peace conceptions are also expected to be present;

• regarding gender differences, we expect boys to refer more often to politics and internationally related contents, while girls representations may include more intrapersonal elements;

• assuming that the development of peace and war concepts should be completed within preadolescence, we do not expect to find significant differences related to age, yet a few differences related to school year might emerge;

• finally, we expect that peace education activities play a relevant role: we expect the social representation of peace evoked by students involved in trainings to be more complex and to include more elements related to positive peace conceptions than the representation evoked by other students.

Method

Participants

One hundred and twelve students took part of the study (mean age: 15 years and 8 months, 90.1% of the sample between 14 and 17 of age). There were 39 boys (34.8%) and 72 girls (64.3%), of which 55 attended the first (49.1%), 27 the second (24.1%), and 29 the third grade (25.9%) of the same two high secondary schools2 located in the city of Venice.

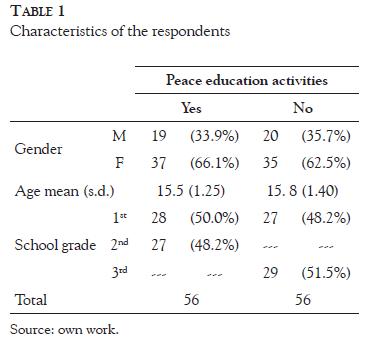

This convenience sample was extracted from a wider database, in order to be balanced according to our main variable of interest: participation in peace education activities. These were organized by teachers involved in a local network coordinated by the city of Venice, specifically aimed at promoting a peace culture. Activities included indepth coursework and lessons about contemporary topics or within the school curriculum. The two groups are similar in terms of gender and age, with a few differences in terms of school grade (Table 1).

Instrument

A questionnaire with different sections was employed for data collection3. Social representations were explored via free associations tasks to the stimuli War and Peace. Stimuli were proposed separately, and randomly. Respondents were asked to report the first five associations that came to their minds related to each stimulus. Data were gathered in May, 2006.

Procedure

After the necessary permissions had been obtained, students were reached in their classrooms. They were invited to complete the instrument individually. The text corpus was first processed to reduce ambiguities and data dispersion. This phase followed conservative criteria: synonyms and different grammar forms- gender, singular/plural- were grouped together. The resulting corpora (War–578 total occurrences, 166 different forms; Peace–490 occurrences, 154 forms) were submitted to two different analyses.

The overall structures of the representations of peace and war were explored via prototypical analysis (Vergès, 1992), with the aid of Evocation software (Vergès, Scano & Junique, 2002). It is a procedure that is directed towards the assessment of salience that is relative to representation contents. It is based on free association tasks, through the evaluation of two criteria: the frequency of evoked words and their elicitation order, which is also referred to as evocation rank. The crossing of those dimensions allows for a definition of four quadrants: contents more often and in average as the first ones in discourse –high frequency and low rank– are those that compose the central core of the representation. Highly frequent but late-recalled words form the high peripheral zone –high frequency and rank– and those that come around less often and also late constitute the low peripheral zone, which is more subject to variation. There is then a fourth quadrant, the contrast zone, in which it is possible to find a few elements that express contents of subgroups or that signal a possible change of the representation. That zone comprises the contents that are mentioned early, but only by a restricted number of people – low frequency, low rank. Finally, words with extremely low frequencies are considered as idiosyncratic expressions that are not part of the social representation. Operationally, the current investigation adopted a split based on the mean rank of all associations to define the cut-off point for the evocation rank criterion. Regarding frequency, cut-off points to distinguish among high, low and idiosyncratic contents were determined through a qualitative comparison of the frequency distribution pattern relative to associations with the expected distribution (Zipfs law).

A second type of analysis-specificities analysis (Vospec procedure, SPAD software)- was conducted to investigate which terms were particularly associated to War and Peace by different groups of respondents. This procedure is based on the comparison between the frequency observed in a class of responses and the one observed in the overall corpus. Comparisons between groups were carried out separately for the associations to each stimulus.

Results are presented in this order: overall structures for the representations of Peace and War shared by the global set of participants are presented first; specificities analyses contrasting participants by gender, by age and by school grade are then presented; finally, separate structures of participants who had and had not taken part in peace training activities are deepened.

Results

War, contents and structure of the representation

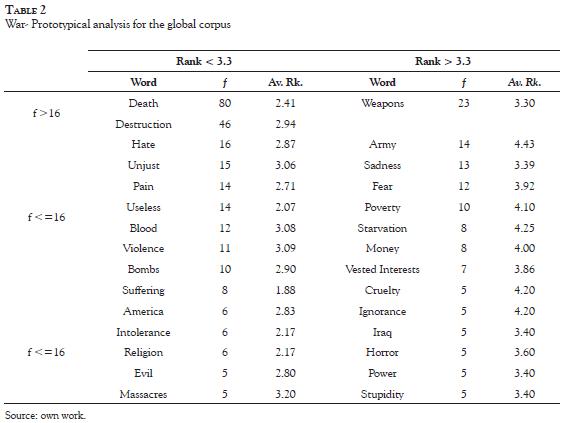

Coherently with data reported in literature, the social representation of war appears to be highly structured around an evocative core (Table 2).

War first and foremost evokes images of death and destruction4. Death is among the first terms evoked by almost all participants, and is likely to be a central element. The first peripheral zone includes only weapons, an element that goes back to the earlier development of the concept of war. Elements included in the contrast zone are very far from the core and do not seem to challenge the stability of the representation. Taken together, the contrast and the peripheral zones refer to three main areas: experience, objects and causes of wars. Experiences are strictly linked to the core; they include lively images such as blood, violence, and massacres, or also poverty and starvation, but also emotional elements related to perpetrators- hate, evil, cruelty- and victims- pain, suffering, sadness, fear and horror. Objects included material aspects- bombs, army. Finally, the last area collects elements that are useful to understand the outbreak of wars. Causes are linked with religion, money and power, however, war is difficult to understand, as it is characterized by a lack of sense: it is unjust and useless, guided by ignorance and stupidity. Concluding, it is worth noting some absences. War seems to take place in an unidentified “elsewhere”, as there are no geographical references apart from America and Iraq. Moreover, elements related to Italian history, politics, or to the Italian armed forces, that were involved in several missions at the time the research was conducted, are missing in the representation of war.

Peace, contents and structure of the representation

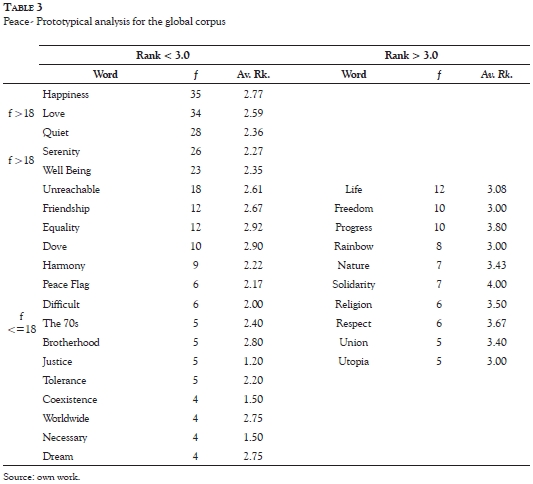

The social representation of peace expressed by the participants is also in line with the literature (Table 3). Peace does not elicit vivid images as the one induced by War; it is somehow bounded to abstract reasoning. The core is based on intimate and positive emotional experiences such as happiness and love (Hakvoort & Oppenheimer, 1998). Three elements included in the contrast zone are near to the core, and thus indicate the possibility of structural changes or the existence of subgroups characterized by different representations. They refer to the issue of utopia –unreachable-, to interpersonal attitudes– friendship- (Hakvoort & Hägglund, 2001) and to positive peace conceptions- equality. Also in this case, however, the link between the contrast zone and the peripheral elements appear to be more relevant. It is possible to distinguish three main themes: inner peace, utopia, and peace-building elements. First, intimate experiences and emotions are crucial for the representation of peace and constitute its central core. A second group gathers associations related to the sphere of utopia and symbolism. Peace is described as unreachable, it is a dream or a utopia, and it is described through symbols such as dove, peace flag and rainbow, and through bucolic images summarized by the category nature. A third facet gathers elements that are necessary to get to- or that following Mahatma Gandhis famous stance define the ways of- peace (equality, justice, tolerance, solidarity, respect, coexistence), i.e. elements that refer to a positive approach to peace.

It can also be noticed that some themes are excluded from the representation of Peace. First, a political dimension is missing; the absence of international organizations (e.g. U.N.) is particularly relevant as it is at the base of juridical pacifism (Bobbio, 1983/1990). Secondly, places, structures, association or groups where equality, justice and tolerance can be enacted are not defined, thus leaving these themes at a conceptual dimension.

Differences by gender, age and school grade

Differences between participants have been investigated by mean of specificities analysis (Table 4). Gender differences support expectations only marginally, especially regarding the representation of War: boys refer more to political actors. It can be noticed that specific associations evoked by girls refer to the dimension of social justice (i.e. poverty vs. equality).

Age, unexpectedly, is also linked to specific contents. As regards peace, 14-year-old participants refer to symbols (i.e. rainbow, dove) and to a personal level (calm, smile). Respondents from 15 to 19 years old include also other levels (e.g. worldwide, non-violence, Third-world). It is possible to notice some antinomies between peculiar associations to war and peace such as indifference-understanding (15 years olds) and violence-non violence (16 years olds). Finally, as expected, school grade accounts for differences in the explored representations. Moreover, specificities refer to different dimensions across school year. First-year students refer to justice (e.g. innocents vs. justice). Second-year students focus on experiences (e.g. destruction vs. quiet), and third- year students adopt the dimension of power (e.g. power vs. utopia).

Comparison between groups involved or not involved in peace related activities

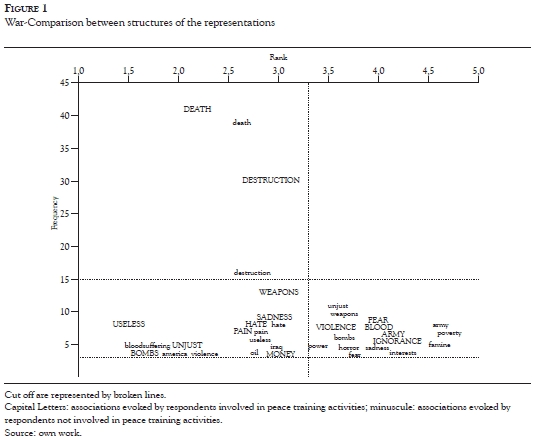

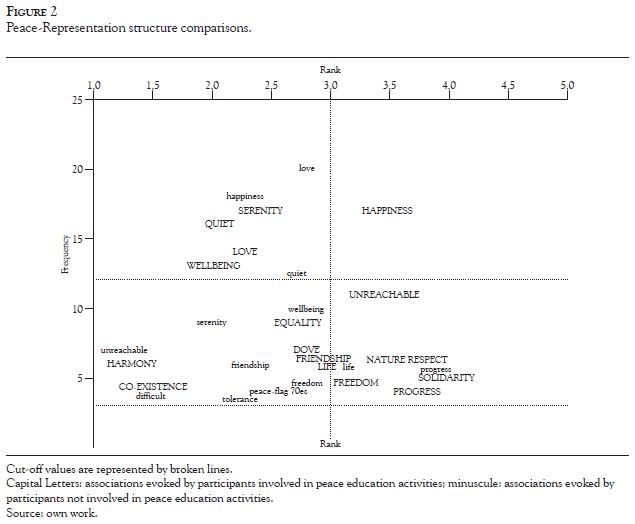

As expected, the structures of the social representations of peace shared by those who took part or who did not participate in peace education activities show relevant differences. The representations of war appear to be more stable across groups.

Regarding war (Figure 1), the central core of the representation is coherently defined by death and destruction in both groups. The remaining associations constitute large contrast and second peripheral zones that are almost overlapped across groups, replicating the contents already described in the overall representations: experience, objects and causes of wars.

Also in the case of peace (Figure 2) the kernel is stable, thus confirming the uniqueness of the representation, structured around intimate and positive emotional experiences. More relevant are the differences in the peripheral areas. Those who took part on peace trainings include in the representations several elements related to positive approaches to peace. Coexistence and equality are in the contrast area, and the latter appear on the border with the central core; moreover, respect and solidarity are present in the peripheral zone of the representation. These four terms do not appear in the representation shared by respondents who did not participate in peace related activities. On the contrary, the link between peace and unreachable is stronger in this second group (the average evocation rank is much lower) and only that group includes utopia and religion among the peripheral elements.

Discussion

Overall, results provide evidence that peace and war have structured representations, both of them with organized central cores. In agreement with studies conducted in different times and contexts (Cooper, 1965; Hakvoort & Oppenheimer, 1998) the representation of war is particularly stable, it reproduces lively images and is rooted in earlier development conceptions: the object –actions– consequences triad. In contrast, the causes and historical and political implications seem to have less space. It is interesting to stress the emergence also in our respondents of a strong association between war and destruction, both at the material and moral levels. This is in line with the results of previous studies conducted with adolescents from Italy and Germany (Sbandi, 1988; Dinklage & Ziller, 1989), the two European countries that were defeated in World War II.

The representation of peace that has been brought to light presents both continuity aspects with what has been described by the literature as well as some elements that indicate the evolution that has been taking place for a few years. Positive emotional experiences and links with utopia remain the central themes of the representation of peace (Hakvoort & Oppenheimer, 1998; Pagnin, 1992). In addition, it is possible to stress the difficulty on part of the teenagers to include causes and spaces for personal action on the evoked representations. The idea that war is due to economic reasons shows in fact a generic motivation and does not emphasize the single responsible actors –e.g. governments, ministers, parliament, dictators, generals– who consequently disappear in the background. As counterproof, the social representation of peace does not take into account “juridical”, “economic” and “social” approaches, which foster peaceful relations among States (Bobbio, 1983/1990). Nevertheless, there is evidence of features related to a complex and positive conception of peace (Galtung, 1996; Hakvoort & Hägglund, 2001). The simultaneous reference to contents that connect peace with utopia and to the positive peace shows the polyphasic nature of representations that “is itself linked to a dynamic of change within the community” (Wagner et al., 2000, p. 312). This seems to agree with a progressive inclusion of themes that are related to a positive conception towards more central zones of the representation of peace: a process that has been identified in Italy since 2004 (Sarrica, 2007).

The influences of design variables such as gender and grade on representation structures were also observed. However, their effects were small, limited to minor peripheral modulations.

Special attention has been directed towards the comparison of classes that had been involved or not in peace education activities. In structural terms, the difference between taking part in activities or not relates to the first meaning of practices mentioned by Flament and Rouquette (2003): the passing to action, i.e. the difference between having done something or taken part in some kind of experience, and not having done it that can be seen from differences on the systems of the representations. An alternative interpretation, following Wagner (1994), would be that some students had the opportunity of enhancing their own representational repertoire, which includes behaviors along with cognitions. The social representations expressed by participants involved in the activities is actually characterized by higher level of complexity, and the resulting broader range of available interpretations is found among the peripheral elements that manage situational variability. Therefore, rather than developing different representations, the active participation of teenagers seems to have promoted a widening of experiences and a tendency to provide alternative interpretations of peace. Conversely, as expected, there were no differences regarding the representation of war, confirming that it is a more structured representation with more strongly shared contents and that it is more difficult to generate debates and sidings on such a deeply objectified construction.

A last issue is linked to the relationships maintained by both representations. The study did not have the specific aim of investigating that type of connection, but its results allow for some brief comments on the topic. As Peace and War are commonly taken as opposite notions, one might be tempted to think that they are found in a relationship of antinomy, the coordination type identified by Guimelli and Rouquette (2004). If representation contents are assessed independently from structure, that might hold true; there is death in war and life in peace, just as there is love in peace and hate in war. However, if representation structure is taken into account, then the antinomy relationship must concern elements within representations cores, which define their identities (Abric, 1994a, 1994b). A close examination of our results reveals that the antonyms to central core elements can only be found on the peripheral system of the other representation. That is the case of the mentioned examples: love is a central element linked to peace, but hate is only in the contrast zone of the representation of war, with a low frequency. Likewise, death is central for war, but life is on the low peripheral zone related to peace, with both low frequency and rank. The same pattern is repeated for all the possible antonyms to central core elements. Therefore, our results do not support the identification of an antinomy relationship involving the representations of peace and war. They are conceptions based on different themes. They appear to be constructs that take their foundations from different symbolic families or ideologies; i.e., war refers to death, to a concrete catastrophe and to how it can be experienced directly, while peace relates to a subjective emotional state of calm, happiness. This result may also explain why it is possible to contemporary be at war and in peace, as in the few lines quoted in our starting excerpt.

Finally, it is necessary to point out some methodological limits of the current study. First, it is important to make it clear that the investigation is not able to assess representational dynamics, as it does not have a longitudinal design. Consequently, it is not possible to conclude about the permanence, decrease or strengthening of its contents. A second limit is related to the free association task, technique that has been employed for data collection. Evocation material reduces the possibilities of a full exploration of the complexity of the studied concepts in discourse, especially concerning the representation of peace (Hakvoort & Hägglund, 2001). Moreover, in a strict sense, free associations and prototypical analyses allow only for the formulation of centrality hypothesis. Other procedures, such as the ones based on the questioning –miseen-cause– principle (Moliner, 1994, 2001), or on the activation of basic cognitive schemes (Guimelli & Rouquette, 1992), among others, aim at a more precise identification of the central core and of relevant structural dimensions. However, those techniques demand previous knowledge of representation contents. For that reason, it is a logical next step to plan further investigations with those techniques, based on the results provided by the current study.

Concerning the relevance of the presented results for applied efforts, the data are not to be understood as evaluations of peace training activities, but it is still possible to stress that the adolescents who had taken part in activities expressed richer representations of peace. This result provides support to the choice of promoting moments for peace education at schools. An empirical analysis shows that the capacity of promoting free and open discussion does not favor a simple gain of notions and concepts; rather, it is associated with the emergence of rich social representations that allow for a more articulate and flexible understanding of the social reality that adolescents have to face in everyday life, and that is even more relevant.

References

Abric, J. C. (1984). L artisan et lartisanat: analyse du contenu et de la structure dune représentation sociale. Bulletin de Psychologie, 37(366), 861-875. [ Links ]

Abric, J. C. (1994a). L organisation interne des représentations sociales: système central et système périphérique. In C. Guimelli (Ed.), Structures et transformations des représentations sociales (pp. 73- 84). Lausanne: Delachaux et Niestlé. [ Links ]

Abric, J. C. (1994b). Les représentations sociales: aspects théoriques. In J. C. Abric (Ed.), Pratiques sociales et représentations (pp. 11-36). Paris: PUF. [ Links ]

Ålvic, T. (1968). The development of views on conflict, war, and peace among school children: A Norvegian case study. Journal of Peace Research, 5(2), 171-195. [ Links ]

Anderson, R. (2004). A definition of Peace. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 10(2), 101- 116. [ Links ]

Bobbio, N. (1983/1990). Pacifismo. In N. Bobbio, N. Matteucci & G. Pasquino (Eds.), Dizionario di politica (pp. 745-747). Torino: TEA. [ Links ]

Bombi, A. S., Cristante, F. & Talevi, A. (1983). The representation of peace and war in Italian children. Paper presented at the 7th Biennial Meeting ISSBD, Munchen, Germany. [ Links ]

Burnham, J. J. (2007). Childrens fears: A pre-9/11 and post-9/11 comparison using the American Fear Survey Schedule for children. Journal of Counseling and Development, 85(4), 461-466. [ Links ]

Christie, D. J., Wagner, R. V. & Winter, D. A. (Eds.). (2001). Peace, conflict, and violence: Peace Psychology for the 21st century. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Cooper, P. (1965). The development of the concept of war. Journal of Peace Research, 2(1), 1-17. [ Links ]

Dinklage, R. I. & Ziller, R. C. (1989). Explicating cognitive conflict through photo-communication. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 33(2), 309-317. [ Links ]

Flament, C. & Moliner, P. (1989). Contribution expérimentale à la Théorie du Noyau Central dune Représentation. In J. L. Beauvois, R. V. Youle & J. M. Monteil (Eds.), Perspectives cognitives et conduites sociales (Vol. 2, pp. 139-142). Cousset: Del Val. [ Links ]

Flament, C. & Rouquette, M. L. (2003). Anatomie des idées ordinaires. Paris: Armand Colin. [ Links ]

Flament, C. (1989). Structure et dynamique des représentations sociales. In D. Jodelet (Ed.), Les représentations sociales (pp. 204-219). Paris: PUF. [ Links ]

Flament, C. (1994). Aspects périphériques des représentations sociales. In C. Guimelli (Ed.), Structures et transformations des représentations sociales (pp. 85-118). Lausanne: Delachaux et Niestlé.

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by peaceful means: Peace and conflict, development and civilization. Oslo: Sage. [ Links ]

Galtung, J. & Tschudi, F. (2001). Crafting Peace: On the Psychology of the TRANSCEND Approach. In D. J. Christie, R. V. Wagner & D. A. Winter (Eds.), Peace, conflict and violence: Peace Psychology for the 21st Century (pp. 210-222). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Guimelli, C. (1989). Pratiques nouvelles et transformation sans rupture dune représentation sociale: la représentation de la chasse et de la nature. In J. L. Beauvois, R. V. Joulé & J. M. Monteil (Eds.), Perspectives cognitives et conduites sociales (Vol. 2, pp. 117-138). Cousset: Del Val. [ Links ]

Guimelli, C. & Rouquette, M. L. (1992). Contribution du modèle associatif des schèmes cognitifs de base à lanalyse structurale des représentations sociales. Bulletin de Psychologie, 45(405), 196-202. [ Links ]

Guimelli, C. & Rouquette, M. L. (2004). Étude de la relation dantonymie entre deux objets de représentation sociale: la sécurité vs. linsécurité des biens et des personnes. Psychologie & Société, 4,1(7), 71-87. [ Links ]

Hakvoort, I. & Hägglund, S. (2001). Concepts of peace and war as described by Dutch and Swedish girls and boys. Journal of Peace Psychology, 7(1), 29-44. [ Links ]

Hakvoort, I. & Oppenheimer, L. (1993). Children and adolescents conceptions of peace, war and strategies to attain peace: A Dutch case study. Journal of Peace Research, 30, 65-77. [ Links ]

Hakvoort, I. & Oppenheimer, L. (1998). Understanding peace and war: A review of Developmental Psychology research. Developmental Review, 18, 353-389. [ Links ]

Hakvoort, I. & Oppenheimer, L. (1999). I know what you are thinking: The role-taking ability and understanding peace and war. In A. Raviv, L. Oppenheimer & D. Bar-Tal (Eds.), How children understand war and peace: A call for international peace education (pp. 59-77). San Francisco: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Harris, I. M. (2004). Peace Education Theory. Journal of Peace Education, 1(1), 5-20. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (Ed.). (1989). Les représentations sociales. Paris: PUF. [ Links ]

Lheureux, F., Rateau, P. & Guimelli, C. (2008). Hiérarchie structurale, conditionnalité et normativité des représentations sociales. Cahiers Internationaux de Psychologie Sociale, 77, 41-55. [ Links ]

Mack, J. E. & Snow, R. (1986). Psychological Effects on Children and Adolescents. In R. K. White (Ed.), Psychology and the prevention of nuclear war (pp. 16-33). New York: NYU. [ Links ]

McLernon, F. & Cairns, E. (2006). Childrens attitudes to war and peace: When a peace agreement means war. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 272-279. [ Links ]

Moliner, P. (1989). Validation expérimentale de l hypothèse du noyau central des représentations sociales. Bulletin de Psychologie, 42(387), 759-762. [ Links ]

Moliner, P. (1994). Les méthodes de repérage et didentification du noyau des représentations sociales. In C. Guimelli (Ed.), Structures et transformations des représentations sociales (pp. 199-232). Lausanne: Delachaux et Niestlé. [ Links ]

Moliner, P. (2001). Une approche chronologique des représentations sociales. In P. Moliner (Ed.), La dynamique des représentations sociales (pp. 245- 268). Grenoble: PUG. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (1961/1976). La Psychanalyse, son image, son public. Paris: PUF. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (1992). Présentation. Bulletin de Psychologie, 45(405), 137-143. [ Links ]

Orr, E., Sagi, S. & Bar-On, D. (2000). Representations as collective coping and defense. Papers on Social Representations, 9, 1-20. [ Links ]

Pagnin, A. (1992). Rappresentazione della guerra e giudizio morale in adolescenti. In E. Ponzo & G. Tanucci (Eds.), La Guerra Nucleare. Rappresentazioni Sociali di un Rischio (pp. 215-229). Milano: Angeli. [ Links ]

Pecjak, V. (2003). Verbal associations with sociopolitical concepts in three historical periods. Studia Psychologica, 35, 4-5. [ Links ]

Ponzo, E. & Tanucci G. (Eds.). (1992). La Guerra Nucleare. Rappresentazioni Sociali di un Rischio. Milano: Angeli. [ Links ]

Raviv, A., Oppenheimer, L. & Bar-Tal, D. (Eds.). (1999). How children understand war and peace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, S. (2005). Las y los ciudadanos de Bogotá significan la paz. Universitas Psychologica, 4(1), 97-106. [ Links ]

Rouquette, M. L. (1998). Representações e práticas sociais. In A. S. P. Moreira & D. C. de Oliveira (Eds.), Estudos interdisciplinares de representação social (pp. 39-46). Goiânia: AB. [ Links ]

Rouquette, M. L. & Guimelli, C. (1995). Les “canevas de raisonnement” consécutifs à la mise en cause dune représentation sociale: essai de formalisation et étude expérimentale. Cahiers Internationaux de Psychologie Sociale, 28, 32-43. [ Links ]

Sarrica, M. (2007). War and peace as social representations. Cues of structural stability. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 13(3), 251-272. [ Links ]

Sarrica, M. & Contarello, A. (2004). Peace, war and conflict. Social representations shared by peace activists and non activists. Journal of Peace Research, 41(5), 549-568. [ Links ]

Sbandi, M. (1988). LImmagine della Guerra in Età Evolutiva. Età Evolutiva, 31, 41-47. [ Links ]

Spielmann, M. (1986). If peace comes future expectations of Israeli children and youth. Journal of Peace Research, 23(1), 51-67. [ Links ]

Vergès, P. (1992). Évocation de largent: une méthode pour la définition du noyau central dune représentation. Bulletin de Psychologie, 45(2), 203-209. [ Links ]

Vergès, P., Scano, S. & Junique, C. (2002). Ensembles de programmes permettant lanalyse des évocations (Manual). Aix en Provence: Université Aix en Provence. [ Links ]

Vriens, L. (1999). Children, war and peace: A review of fifty years of research from the perspective of a balanced concept of peace education. In A. Raviv, L. Oppenheimer & D. Bar-Tal (Eds.), How children understand war and peace: A call for international peace education (pp. 27-58). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Wagner, W. (1994). The fallacy of misplaced intentionality in social representation research. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 24, 243-266. [ Links ]

Wagner, W., Duveen, G., Verma, J. & Themel, M. (2000). I have some faith and at the same time I dont believe. Cognitive polyphasia and cultural change in India. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 10, 301-314. [ Links ]

Wagner, W., Valencia, J. & Elejabarrieta, F. (1996). Relevance, discourse and the “hot” stable core of social representations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 331-351. [ Links ]

Recibido: junio 29 de 2009

Revisado: septiembre 12 de 2009

Aceptado: septiembre 14 de 2009

Para citar este artículo. Sarrica, M. & Wachelke, J. (2010). Peace and War as Social Representations: A Structural Exploration with Italian Adolescents. Universitas Psychologica, 9 (2), 315-330.

* Research article.

** Dipartimento di Psicologia Applicata, Via Venezia, 8-35131-Padova, Italia. E-mails: mauro.sarrica@unipd.it; wachelke@yahoo.com

1 http://politicalhumor.about.com/library/blbushisms2002.htm retrieved March, 4, 2008.

2 58 respondents attended a social science school, 54 were enrolled at a scientific school. Differences in results related to the typology of school are extremely limited. Thus, this variable will not be discussed.

3 The questionnaire is part of a wider research. Other sections investigated the representations on citizenship and participation, perceived social well being, media use and information sources.

4 The lexical forms evoked by respondents are presented in Italics.