Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.24 no.1 São Paulo jan./abr. 2022

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPCP13295.en

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

Group Interventions with Mothers and Children Exposed to IPV: a systematic literature review

Intervenções com grupos de mães e filhos expostos à VPI: uma revisão sistemática de literatura

Intervenciones con grupos de madres y niños expuestos a la violencia de género: una revisión sistemática de la literatura

Alliny T. M. OtaguiriI ; Aline C. SiqueiraII

; Aline C. SiqueiraII ; Sabrina M. D'AffonsecaI

; Sabrina M. D'AffonsecaI

IPostgraduate Program in Psychology, Laboratory for Analysis and Prevention of Violence, Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar)

IIPostgraduate Program in Health Sciences and Psychology, Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM)

ABSTRACT

This study had the objective to conduct a systematic literature review on interventions aimed at children and their mothers exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV). A search in the Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and Bireme databases was conducted using the terms "violência doméstica/domestic violence", "violência entre parceiros íntimos/ intimate partner violence/ violencia entre parejas íntimas", "crianças/ children/ niños", "expostas/ exposed/ expuestos", "intervenção/ intervention/ intervención", "tratamento/ treatment/ tratamiento", "grupo/ group". Through inclusion/ exclusion criteria, the studies were selected and analyzed. Thirteen studies were analyzed and it was observed a predominance in pre-post-test studies with parallel groups of mothers and children. The objectives focused on symptoms (trauma, anxiety, depression, behavior problems) and strengthening mother-child bonds. Conducting concomitant treatment was associated with positive results in reducing symptoms and negative consequences of IPV exposure. These findings shed an important light on violence prevention and intervention, suggesting that concomitant mother-child treatment favors the development of positive and healthy relationships between them.

Keywords: violence between intimate partners, exposure, intervention, mothers, kids

RESUMO

O presente estudo teve como objetivo realizar uma revisão sistemática da literatura de intervenções voltadas para crianças e suas mães expostas à violência por parceiro íntimo (VPI). Foi realizada uma busca às bases de dados Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science e Bireme utilizando os termos "violência doméstica/domestic violence", "violência entre parceiros íntimos/intimate partner violence/violencia entre parejas íntimas", "crianças/children/ niños", "expostas/exposed/expuestos","intervenção/intervention/intervención","tratamento/treatment/tratamiento", "grupo/group". A partir dos critérios de inclusão/exclusão, os estudos foram selecionados e analisados. Nos 13 estudos analisados, verificou-se predominância de estudos pré e pós-teste com grupos paralelos de mães e crianças, com objetivos voltados aos sintomas (trauma, ansiedade, depressão, problemas de comportamento) e fortalecimento de vínculo mãe-filho. A condução de tratamento concomitante associou-se a resultados positivos na redução de sintomas e consequências negativas da exposição à VPI. Tais achados lançam uma luz importante para a área de prevenção e intervenção sugerindo que o tratamento concomitante mães-filhos favorece o desenvolvimento de relações positivas e saudáveis entre eles.

Palavras-chave: violência por parceiro íntimo, exposição, intervenção, mães, crianças

RESUMEN

El presente estudio tuvo como objetivo conducir una revisión sistemática de la literatura de intervenciones dirigidas a los niños y sus madres expuestos a la violencia entre parejas íntimas (VPI). Fueran realizadas búsquedas en las bases de datos Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science y Bireme utilizando los términos "violência doméstica/domestic violence", "violência entre parceiros íntimos/intimate partner violence/violencia entre parejas íntimas", "crianças/ children/niños", "expostas/exposed/expuestos", "intervenção/intervention/intervención", "tratamento/ treatment/ tratamiento", "grupo/group". A partir de los criterios de inclusión/exclusión, los estudios fueron seleccionados y analizados. Em los trece estúdios analizados, hubo un predominio de los estudios con análisis pre-pos testes con grupos paralelos de madres y niños, con objetivos centrados en los síntomas (trauma, ansiedad, depresión, problemas de comportamiento) y en el fortalecimiento del vínculo madre-hijo. La realización de un tratamiento concomitante se asoció con resultados positivos en la reducción de los síntomas y las consecuencias negativas de la exposición a VPI. Estos resultados hallazgos arrojan una luz importante sobre el área de prevención e intervención, lo que sugiere que el tratamiento concomitante de madre e hijo favorece el desarrollo de relaciones positivas y saludables entre ellos.

Palabras clave: violencia entre parejas íntimas, exposición, intervención, madres, niños

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a reality in many households around the world and is not limited by boundaries of social class, race/ethnicity, religion, age, or education. It is one of the most frequent assaults in the world, and the data concerning its prevalence is alarming. The World Health Organization (WHO) reveals, from studies published between 2014 and 2016, regarding 79 countries, that one in three women has experienced intimate partner violence, and 42% of women who have been physically and/or sexually abused by their partner have suffered injuries because of the assaults (WHO, 2014, 2016).

Although not all women are mothers, a considerable number of women exposed to IPV have children, and a woman with children is three times more likely to experience IPV than women who do not have children (Humphreys, 2007). Kistin and Bair-Merritt (2017) estimate that at least 15 million children are exposed to IPV in their homes, and many of them also face violence in their communities and/or through the media. The authors point out that statistics regarding the number of children exposed to violence can vary when considering: 1. the type of violence (physical, psychological, sexual, economic, moral); 2. the measure used to determine exposure; and 3. the method of data collection.

There is no precise data related to the number of children exposed to IPV in Brazil, because, according to Pinto Junior et al. (2017), most research in the country uses indirect measures to assess exposure - commonly based on mothers' reports - and rough estimates, based on the number of women who claim to be in a relationship that includes IPV.

Exposure to IPV can lead to short and long-term damaging developmental consequences for both the woman who is a victim and her children. Women in a relationship in which there is IPV are more likely to experience physical, sexual, and reproductive health problems and chronic illnesses (Lutwak, 2018; WHO, 2014). In addition to the obvious injuries, wounds, or physical marks from IPV, many women experience mental health problems, and the most common are depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder - PTSD (Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graf, 2015; Lutwak, 2018; WHO, 2014, 2016). However, other symptoms experienced by these women are associated with IPV, such as suicidal thoughts/attempts, eating disorders, sleep disorders, alcohol, and drug abuse (Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graf, 2015; Lutwak, 2018; WHO, 2014, 2016). Besides, feelings of loneliness, social isolation and restricted access to support, medical care, and legal assistance are common (Lutwak, 2018; WHO, 2014, 2016).

Studies have shown that a child's exposure to IPV has an impact on his/her development, both directly (Graham-Bermann & Perkins, 2010; Harris, 2017; Holmes, 2013; Timmer et al., 2010) and indirectly. The psychological damage of the mother who suffers aggression can indirectly affect her children, due to the relationship established between them (Patias et al., 2014). The possible direct consequences of the child's exposure to violence are symptoms of anxiety, depression, or stress (Kistin & Bair-Merritt, 2017), behavioral problems, and/or learning problems (Moffitt, 2013). Chronic exposure can lead to extensive damage to the physical and psychosocial health of this population (Kistin & Bair-Merritt, 2017; Moffitt, 2013), which can lead to major problems in the long term.

Research highlights the damage to the mental health of the mother victim of IPV and how this interferes with her relationship with her children (Carlson et al., 2019; Graham-Bermann et al., 2011; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015; Levendosky et al., 2006; WHO, 2014; Silva et al., 2017; Visser et al., 2015). Such studies reveal that high rates of maternal depression, stress, and PTSD are important factors to be aware of in this context. The absence of positive parenting practices, inconsistent and coercive disciplinary practices, high rates of inappropriate discipline, inhibition of positive and nurturing interactions, emotional detachment, and neglect are reported more frequently in mothers with a history of IPV (Carlson et al., 2019; Graham-Bermann et al., 2011; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015; Levendosky et al., 2006; WHO, 2014; Silva et al., 2017; Visser et al., 2015).

Furthermore, a child's exposure to IPV constitutes a risk factor for child maltreatment (Harris, 2017; Howarth et al., 2016). Harris (2017) estimates that co-occurrence rates among IPV and child abuse are between 30% and 60%, which signals the correlation between these two phenomena.

Positive and healthy relationships between members of a family can become important protective factors, since they contribute to the development and strengthening of resilience and coping skills, as well as recovery from adversity (Walsh, 2016). In this context, the review developed by Carlson et al. (2019) highlights that the mothers' skills in the context of IPV are diverse. In some situations, mothering remains positive, and sensitivity and responsiveness toward their children are identified. Also, emotional support, consistency, acceptance, parental involvement, and appropriate disciplinary practices have been associated with successful outcomes in children exposed to IPV (D'Affonseca & Williams, 2011).

It is important to emphasize that the effective addressing of children's exposure to IPV cannot be solved with a single approach, because this phenomenon is very complex. Therefore, services are needed in the school, health, justice, and social assistance systems for this population, both for prevention and for treatment of those who are already exposed (Kistin & Bair-Merritt, 2017).

Positive mother-child relationships can become an important protective factor for individuals in the context of IPV, considering that these relationships can be sources of safety, affection, protection, and well-being. Katz (2015) highlights that mutual support in the mother-child dyad, more pleasant interactions, and strengthening of bonds can help minimize the effects of IPV. It is believed that intervention programs provided for both, mothers and their children, may be a viable alternative to minimize the potential impacts of IPV, since all those involved should be supported and not only the direct victims (D'Affonseca & Williams, 2011; Katz, 2014; Patias et al., 2014). In this context, the present study aimed to conduct a systematic review of the literature about interventions for children and their mothers exposed to IPV.

Method

A systematic literature review was conducted in the Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and Bireme databases, including studies published between 2009 and 2018, using the following keywords: 'domestic violence OR intimate partner violence' AND 'children' AND 'exposed' AND 'intervention OR treatment' and 'group'. Equivalent words in Portuguese (violência doméstica, violência entre parceiros íntimos, crianças, exposição, intervenção, tratamento e grupos), and in Spanish (violencia doméstica, violencia de pareja, niños, exposición, intervención, tratamiento and grupos) were also included, as well as possible different combinations among them.

The inclusion criteria adopted were: studies published in research journals in the last 10 years, including 1. reports of interventions with concomitant groups of children or adolescents and their mothers and/or caregivers, with a history of intimate partner violence; 2. data regarding the results achieved from the intervention; 3. articles available for download; and 4. articles written in Portuguese, English, or Spanish. Papers that did not meet these inclusion criteria, theses, dissertations, and book chapters were excluded from this review.

Procedure

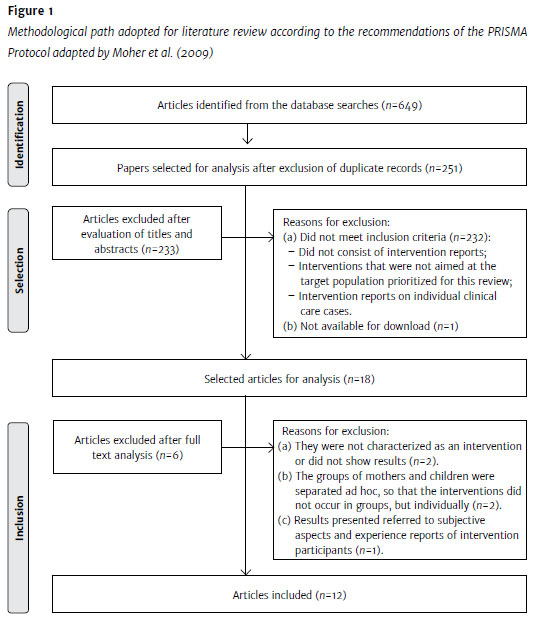

Around 649 registries were identified from the initial database search. After the exclusion of duplicate entries, analysis of the titles and abstracts of 251 articles was performed. A full reading of 18 articles was necessary because it was not possible to identify, from the title and abstract, whether the study met all the inclusion criteria. This procedure ensured that relevant studies were not excluded. At the end of the process, 12 articles were included. The study by Graham-Bermann et al. (2007) was not selected because it is a publication with methodological aspects and results described in two other publications included in the review (Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015). In the end, 13 studies were selected. Figure 1 summarizes the data collection process according to the PRISMA protocol guidelines (Moher et al., 2009).

Results

Table 1 contains a summary of the studies analyzed, sorted according to research group or authors, and by publication date.

After reviewing the articles, it was possible to verify the predominance of studies with groups of school-aged children: seven of the 13 selected studies (53.84%) presented samples of children aged between six and 12 years old. Furthermore, although other studies selected participants with a broader age range, including younger children and adolescents (Grip et al., 2011, 2012, 2013; Pernebo et al., 2018), the mean ages of participants were between 7.4 (SD=2.5) and 10.8 (SD=3) years old. This highlights that interventions conducted with school-aged children were prevalent. Only one of the studies (Graham-Bermann et al., 2015) had children aged between four and six as the target population for the intervention (M=4.93; SD=0.86).

The authors found that most of the studies investigated the forms of IPV and the frequency of its occurrence, since women's history of IPV victimization was an inclusion criterion for participation in all studies. Most studies (n=7; 53.84%) used the Conflicts Tactics Scale (CTS) (Straus, 1979), or the Revised Conflicts Tactics Scale (CTS2) (Straus et al., 1996), and three of them (Graham-Bermann et al., 2007; Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015) also used the Severity of Violence Against Women Scales (SVAWS) (Marshall, 1992). Only one study (Grip et al., 2013) collected data regarding exposure to violence using the Child Exposure to Domestic Violence (CEDV), applied to victims' children (Edleson et al., 2008). Some studies have also assessed the above variables using semi-structured interviews (Grip et al., 2011, 2012).

All selected articles described the use of pre- and post-test measures, and only two (McWhirter, 2011; Pernebo et al., 2018) did not report follow-up measures after treatment. Only three studies worked with an intervention group only, with no control group (Grip et al., 2011, 2012, 2013). Most studies also assessed sociodemographic data (age, income, ethnicity, and education) before the intervention, as well as variables to be analyzed after the intervention in order to identify whether there was a change in the mother-child relationship with the treatment offered to mothers and children.

Studies have also assessed women's health through measures of general mental health (Grip et al., 2013; Pernebo et al., 2018); symptoms of depression (Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015; Graham-Bermann et al., 2011; McWhirter, 2011), anxiety (Graham-Bermann et al., 2011), and trauma (Grip et al., 2011, 2012); physical and psychological symptoms (Grip et al., 2011); PTSD (Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015; Graham-Bermann et al., 2011; Pernebo et al., 2018); psychopathologies (Overbeek et al., 2014, 2017); and alcohol consumption (McWhirter, 2011). Besides, mothers' coping strategies and skills, self-efficacy, readiness for change, confidence, and social support were investigated (McWhirter, 2011).

Children were also assessed for: beliefs and attitudes regarding violence (Graham-Bermann et al., 2007); coping skills (Overbeek et al., 2017); interpersonal relationships, peer conflict (McWhirter, 2011), and family conflict (McWhirter, 2011); psychological well-being (McWhirter, 2011); emotional health and self-esteem (McWhirter, 2011); discrimination of emotions (Overbeek et al., 2017); emotion regulation (Pernebo et al., 2018); internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Graham-Bermann et al., 2007, 2011; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015; Grip et al., 2012, 2013; Overbeek et al., 2013, 2014, 2017; Pernebo et al., 2018); trauma symptoms (Grip et al., 2013); and PTSD (Overbeek et al., 2013, 2014, 2017; Pernebo et al., 2018).

Concerning the mother-child relationship, we collected measures of parental locus of control (Grip et al., 2011); family conflict (McWhirter, 2011); child maltreatment (Overbeek et al., 2013, 2014); attachment (Overbeek et al., 2014); parental stress (Overbeek et al., 2014); parenting practices (Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015, 2011); and parent-child interaction (Overbeek et al., 2014, 2017).

The effectiveness of the interventions was measured using statistical tests and analyses that compared effect measures assessed at the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up to verify the success of the program and the procedures conducted in the intervention. The researchers made use of different programs. The Moms' Empowerment Program (MEP) for mothers' groups, and the The Kids Club program for their children's groups were the most frequent among the studies selected for this review. The MEP, developed by Graham-Bermann and Levandosky (1994), aims to promote the social and emotional adjustment for women who have experienced IPV in the past two years and, consequently, to reduce the effects of IPV on their mental health (Stein et al., 2018).

Over the course of 10 weekly sessions of about two hours of duration each, women share their stories and difficulties in parenting in a safe environment. The focus of the MEP is on the mental health and safety of the participants and their children, as well as developing protective factors for the women, such as social support, community resources, and parenting practices (Stein et al., 2018). The Kids Club, on the other hand, consists of an intervention program designed for children aged from 6 to 12 years old, with a history of exposure to IPV, and aims to reduce behavioral adjustment problems (internalizing and externalizing), and the negative effects of exposure to IPV, encouraging the development of participants' coping skills. Both programs are applied in group sessions, and The Kids Club groups are divided by age groups (Graham-Bermann et al., 2007, 2011; Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015).

The randomized clinical trial by Graham-Bermann et al. (2015), which used MEP's group to treat mothers, was the only one to conduct an intervention with children aged from 4 to 6 years old. To do this, the research used The Pre-Kids Club (PKC) program, an adapted version of The Kids Club, for the age group in question. The PKC, like The Kids Club, consists of a 10-session intervention program that aims to reduce the impacts of IPV exposure on children. The PKC comprises activities regarding beliefs about violence, emotions, fears, and concerns, as well as non-violent conflict resolution (Graham-Bermann et al., 2015). Significant differences were identified between the outcomes of the group receiving the intervention and the control group - results reported a significant reduction in symptoms for children of both genders and a significant decrease in internalizing symptoms for children after the intervention with their mothers.

The studies by Grip et al. (2011, 2012, 2013) reported the use of an adapted version of the Children Are People Too (CAP) program. Originally, CAP targets children whose parents have a history of alcohol and/or drug abuse, and its focus is on parent-child communication, feelings, and beliefs related to violence, and safety planning. The program consists of 10 to 15 sessions, and the children - divided by age groups - participate in playful activities and discussions with psycho-educational content. Also, the program develops interventions for the children's mothers. The three selected publications reported improvements in the mothers' mental health, trauma symptoms, and sense of competence; and reduction of adjustment issues in the children. Despite the positive outcome, individual analyses showed wide variations in results, indicating that most participants did not show individual changes.

McWhirter's (2011) study compared the outcomes of two community-based intervention programs to mothers and children exposed to IPV. Both were structured in five weekly sessions, but one was emotion-focused and the other one was goal-focused. The goal-focused program was based on the cognitive behavioral therapy model, including motivational interviewing and goal-directed change promotion. The emotion-focused program, on the other hand, incorporated activities to improve emotional awareness and positive relationships among group members and used psychoeducational elements based on Gestalt and behavioral psychology concepts (McWhirter, 2011). Although both intervention modalities showed improvements for mothers and children, participants in the goal-focused group were successful in decreasing alcohol consumption and family conflicts. Participants in the emotion-focused group showed better quality social support, according to mothers' reports. In the end, the authors concluded that both intervention modalities are appropriate alternatives in the assistance to the target population.

The studies by Overbeek et al. (2013, 2014, 2017) used two different intervention programs - En nu ik! ("It's my turn now!") and Jijhoorterbij ("You belong"). The program En nu ik! ("It's my turn now!") was developed based on The Kids Club, applied in the studies by Graham-Bermann et al. The program was structured by including specific factors to IPV situations, such as a focus on identifying and expressing emotions, developing feelings of safety and coping skills, creating narratives of the trauma, improving parent-child interactions, and psychoeducational activities (Overbeek et al., 2012). The second program, Jijhoorterbij ("You belong"), was developed especially for these studies, from the analysis of non-specific factors of the original intervention (positive attention, social support, playful activities, positive relationships between group members, positive expectations regarding the program, among others). Both programs also offered intervention for parents of the participating children (Overbeek et al., 2012). The results showed that specific factors may not result in more positive or more significant effects, as the trauma-focused approach is not necessarily the most beneficial, and both intervention modalities can be effective in treating children exposed to IPV (Overbeek et al., 2013, 2014, 2017). Regarding the benefits of the interventions, improvements in internalizing and externalizing behavior problems were observed in children participating in both programs. Better recovery rates for these variables were associated with the absence of attachment disorders in children and with higher rates of psychopathology and parental stress (Overbeek et al., 2014).

Furthermore, in situations of increased exposure to non-specific intervention factors, the reduction of children's trauma symptoms was mediated by higher emotion differentiation skills. Enhanced parental health was identified as an important intervening factor in the children's improvement. Higher quality parent-child interaction was also observed, although it did not mediate a decrease in trauma symptoms. When there was greater exposure to specific factors, an association was found between decreased differentiation of emotions and trauma symptoms and increased coping skills in children (Overbeek et al., 2017). Final analyses concluded that benefits achieved by mothers and fathers assisted by intervention programs were associated with improvement in their children (Overbeek et al., 2014, 2017).

Finally, Pernebo et al.(2018) reported the use of one intervention program with a psychoeducational focus and one intervention program with a psychotherapeutic focus. The first one, with a psychoeducational focus, was based on the CAP program, also used in Grip et al. (2011, 2012, 2013). The program with a psychotherapeutic focus was drawn on psychodynamic and attachment theories and was originally developed for children exposed to IPV with psychiatric symptoms. Topics such as violence, family relationships and dynamics (separations, visitation, daily conflicts), and feelings of fear and guilt were all part of this program, which also targeted improving the relationship between parents and children, as well as reducing the negative effects of IPV exposure on mothers and children.

Data analysis allowed the identification of decreased maternal PTSD symptoms and reduced children's symptoms in both interventions, psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic. The children's symptom improvement was directly related to the mothers' improvement, and children whose mothers achieved less significant results also showed lower benefits from the intervention. Despite the positive results for both groups, greater effect sizes were seen for the psychotherapy program participants, with more reduced symptoms of depression, anger, and dissociation, as well as increased levels of emotion regulation and pro-social behavior (Pernebo et al., 2018).

One of the major difficulties identified in the literature regarding the conduct of interventions with families in situations of violence is related to the adherence and permanence of participants throughout the intervention. Among the studies included in this review, the reported loss or dropout rate was between 4.25% (McWhirter, 2011) and 32.5% (Grip et al., 2012). Graham-Bermann et al. (2007, 2011), Graham-Bermann and Miller (2013), and Graham-Bermann, and Miller-Graff (2015) recorded an 18% dropout/loss rate of participants during their research. McWhiter (2011), which had 94 participants, identified the lowest participant loss rate, with only four participants not completing the research study. The paper by Grip et al. (2012), on the other hand, had the highest rate of participant loss: 32.5% of them left the study between the pre-test and the post-intervention evaluation phases. Finally, the studies by Grip et al. (2011, and Overbeek et al. (2017) did not describe their study's sample loss.

Some authors have reported the reasons for sample loss in their studies. Graham-Bermann et al. (2007, 2011), Graham-Bermann and Miller (2013), and Graham-Bermann and Miller-Graff (2015) outlined instability regarding housing status (n=15), refusal to participate in a second interview (n=14), loss of child custody (n=7), high and unrepresentative income compared to the rest of the sample (n=2), and serious injury or illness (n=2). Overbeek et al. (2013, 2014, 2017) reported that two participants withdrew consent throughout the survey, but they did not provide information regarding the remaining losses. Graham-Bermann et al. (2011, 2015), Grip et al. (2012), McWhriter (2011) and Pernebo et al. (2018) did not report reasons or justifications for participant withdrawals.

Graham-Bermann et al. (2007) compared dropout and loss rates of participants between the control and experimental groups. The control group had lower participant adherence during the initial phase and follow-up (82% of participants remained in the study) when compared to the experimental group (94% remained in the study until the time of follow-up). According to the researchers, the perception of being helped can have an impact on the adherence and permanence of individuals in treatment programs.

Discussion

This systematic review provided a literature review of interventions for children and their mothers, exposed to IPV. All studies presented the interventions and also evaluated their effects, providing key elements for their application in the future. An intervention with evidence of effectiveness and efficacy represents a certified action to be implemented with greater certainty of its effects (Durgante & Dell'Aglio, 2018; Mohr et al., 2009). Also, most studies presented an experimental design, with scientific accuracy.

Overall, positive results were observed for both mother and children groups. Concomitant treatment of mothers and children has been associated with positive outcomes in reducing symptoms and negative consequences of IPV exposure; and improvements in mothers' mental health were related to repairs in children's mental health (Graham-Bermann et al., 2007, 2011, 2015; Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015; Grip et al., 2013; Pernebo et al., 2018; Overbeek et al., 2017). These results support the findings in the literature regarding the impact on the mental health and emotional condition of the mothers victims of IPV on their children (Carlson et al., 2019; Graham-Bermann et al., 2011; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015; Levendosky et al., 2006; WHO, 2014; Silva et al., 2017; Visser et al., 2015).

Moreover, the results of randomized clinical trials support the hypothesis that strengthening the involvement of mothers and caregivers provides more positive outcomes for mothers and children (Katz, 2015). Such findings reveal the relevance of prevention of and intervention in IPV, since concomitant treatment of mothers and children seems to promote the development of positive and healthy relationships between the two of them. This change can become an important protective factor because it contributes to the development and strengthening of resilience, coping skills, and recovery from adversity (Walsh, 2016).

Children exposed to IPV may perceive the parental pair as threatening authority figures or as caregivers who are unavailable or unable to meet their basic needs (Carlson et al., 2019). Strengthening these bonds may help the child to develop a different view, and the mother to react differently. This change could contribute to the prevention and treatment of emotional and behavioral problems in their children, as evidenced by the studies' results that assessed the children after the intervention.

Regarding the results presented after the intervention, it was possible to identify that much of the data was obtained from the mothers' reports - both about their own symptoms and those of their children. In this regard, Graham-Bermann and Miller (2013) pointed out that they found evidence that some of the participants in their study may have reported lower levels of negative symptoms due to social desirability. D'Affonseca and Williams (2011) found in their review of the literature that all articles chose the women's self-report on the effects of violence on themselves or their children as a source of information. While this is an important source of information, individuals tend to attribute attitudes or behaviors with socially desirable values to themselves and to reject the presence of attitudes or behaviors with socially undesirable values (Almiro, 2017). The effect of social desirability can be an important limitation to consider when analyzing the results. Thus, it is suggested that future research include measures that assess the effects of social desirability (Almiro, 2017) or incorporate a multi-method approach (Shaughnessy et al., 2012), using mothers, their children, and, if possible, other informants as a source of information.

Graham-Bermann and Miller-Graff (2015) and Grip et al. (2011) suggested the evaluation of mental health professionals and the observation of mother-child interaction - before and after the intervention - as a strategy to assess changes in the relationship, in order not to rely exclusively on the participants' self-report. Such data analysis was carried out in the Partnership Project (Williams et al., 2014); in the same direction, Graham-Bermann et al. (2007) and Graham-Bermann and Miller (2013) used specific instruments and other sources of information to check for reporting biases; and Overbeek et al. (2013, 2014, 2017) adopted other sorts of information to analyze their results.

The study by Grip et al. (2012) pointed out that mothers' psychological health may have influenced their perception and self-report regarding their parenting skills, their ability to cope with children's difficulties and problems, and concerning their children's behaviors. Visser et al. (2015) suggested that mothers who are victims of IPV might underestimate the degree of their children's exposure to violence as well as the consequences experienced by them. This bias may be related to avoidance behaviors, i.e., children's behavior evokes the trauma of victimization, and so mothers tend to avoid them. There is also the possibility of mothers becoming more focused on themselves due to the IPV victimization, compromising their ability to care for their children's needs (Visser et al., 2015).

Overbeek et al. (2013) question the generalizability of their findings, suggesting that the interventions were conducted in controlled situations and may not match the "real world". Situations of violence are complex and require broad intervention that includes a range of elements dependent on diverse contexts, such as health services, the justice system, social welfare, support network strengthening, and safety planning (Howarth et al., 2016). The findings of Overbeek et al. (2017) show that community programs generally perform under less controlled conditions, attend heterogeneous populations, and have fewer resources. Therefore, besides the implementation of an intervention program aimed at the population, it is necessary to train and educate professionals in the protection system. It is essential to make them aware of the complexity of these cases and the situations experienced by this population so that the gains obtained in any type of intervention can be maintained and generalized to other contexts.

Analyzing the conditions of the interventions with populations exposed to IPV, the authors of this review found that the instructors were mostly psychologists, social workers, or counselors, educated or in training, at undergraduate and graduate levels, with expertise in the field of intervention with victims of violence. Several studies have shown the importance of weekly meetings for clinical supervision, case discussion, and review of intervention activities (Graham-Bermann et al., 2007, 2015; Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015). Furthermore, the authors understood that an important factor that favors the success of interventions with populations exposed to violence is the relationship between the therapist/facilitator and the participant (Akin et al., 2016; Howarth et al., 2016). Therefore, the education and training of the professionals working with this population should be considered essential during the development of interventions.

The analysis of the papers revealed that most authors did not report possible reasons for participant dropout rates (Graham-Bermann et al., 2011, 2015; Grip et al., 2012; McWhriter, 2011; Pernebo et al., 2018). The data on dropouts indicate, in line with the current literature, that there are several barriers to be considered: housing situation, work, transportation conditions to the intervention sites, diseases, difficulty in developing bonds between teams and assisted families, among others (Howarth et al., 2016; Silva, 2014). Moreover, it is hypothesized that the dropout of participants is due to the difficult situations, conflicts, and uncertainties experienced by these families (Howarth et al., 2016). Payment to participants may also have interfered with adherence and retention rates in some groups (Graham-Bermann et al., 2007, 2011, 2015; Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013; Graham-Bermann & Miller-Graff, 2015; Overbeek et al., 2013, 2014, 2017). This fact should be discussed in the Brazilian context, where no kind of payment is allowed. Due to ethical issues, it is only permitted to refund possible expenses for travel and food (see Resolution no. 510 of the Brazilian National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde, CNS), which may hinder adherence to intervention programs with this population.

Another significant subject concerns the comparison between individual and group outcomes. For Grip et al. (2013), group and individual results can provide quite different overviews regarding the actual benefits of an intervention. In these authors' study, the results suggested significant gains and decreased negative consequences to IPV exposure for the groups of children. However, individual analysis of the participants showed that few children had benefited significantly. According to Graham-Bermann et al. (2011), one of the aspects responsible for the variations in outcomes among children was the degree of exposure to IPV. The literature indicates that children exposed more intensively to IPV tend to have higher risks of behavior problems (Graham-Bermann & Perkins, 2010; Graham-Bermann et al., 2011; Howarth et al., 2016; Menon et al., 2018). In such cases, the authors recommend that an individual analysis allows the identification of other demands for care and assistance beyond the intervention program.

Final Considerations

The literature review made it possible to verify the panorama of intervention studies with groups of mothers and children exposed to IPV, revealing the state of the art on the subject. The analysis showed the existence of research with well-designed interventions, aligned to an evaluation study. Most studies aimed to compare groups (experimental versus control), with randomization of participants. This research design is considered the most appropriate to produce evidence about the effectiveness and efficacy of the intervention (Mohr et al., 2009).

Regarding the objectives, most interventions aimed to promote the socioemotional adjustment of mothers and children exposed to IPV and also to promote psychological health and well-being. To that end, reduction of trauma, anxiety, and depression symptoms, a decrease of adjustment problems (internalizing and externalizing behaviors), and development and strengthening of coping skills were the contents most found in the studies. Considering the broad scope of the contents, different evaluation measures were used to verify the effects of the interventions, which may have compromised the analysis of the programs' effectiveness. This diversity also made it difficult to reach a consensus among researchers about the contents/aspects that should be addressed in interventions with this population, since each program assessed different domains.

This study allowed the identification of publications from the United States, Sweden, and the Netherlands; and no publications referring to interventions carried out in Latin America were found. Thus, it is essential to promote the adaptation of interventions with groups of mothers and their children for other countries, since violence is a universally present problem. It is also important to evaluate the effects of interventions in different cultures because violence is influenced by specific cultural and social factors.

Although there are limitations in this study, the authors hope that this review will contribute to the dissemination of intervention possibilities with women and children exposed to IPV, and the conduction of research in the field, given the lack of national systematic reviews on this topic.

References

Akin, B., Brook, J., Lloyd, M., Bhattarai, J., Johnson-Motoyama, M., & Moses, M. (2016). A study in contrasts: Supports and barriers to successful implementation of two evidence-based parenting interventions in child welfare. Child Abuse & Neglect, 57,30-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.06.002 [ Links ]

Almiro, P. A. (2017). Uma nota sobre a desejabilidade social e o enviesamento de respostas. Avaliação Psicológica, 16(3),253-386. https://dx.doi.org/10.15689/ap.2017.1603.ed [ Links ]

Carlson, J., Voith, L., Brown, J. C., & Holmes, M. (2019). Viewing children's exposure to intimate partner violence through a developmental, social-ecological, and survivor lens: The current state of the field, challenges, and future directions. Violence Against Women, 25(1),6-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218816187 [ Links ]

D'Affonseca, S. M., & Williams, L. C. A. (2011). Habilidades maternas de mulheres vítimas de violência doméstica: Revisão da literatura. Psicologia Ciência e Profissão, 31(2),236-251. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1414-98932011000200004 [ Links ]

Durgante, H., & Dell'Aglio, D. D. (2018). Critérios metodológicos para a avaliação de programas de intervenção em psicologia. Avaliação Psicológica, 17(1),155-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.15689/ap.2017.1701.15.13986 [ Links ]

Edleson, J. L., Shin, N., & Johnson Armendariz, K. K. (2008). Measuring children's exposure to domestic violence: The development and testing of the Child Exposure to Domestic Violence (Cedv) Scale. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(5),502-521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.11.006 [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann, S. A. (1994). The Moms' Empowerment Program (MEP): A training manual (revised 2011). Department of Psychology, University of Michigan. [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann, S. A., & Perkins, S. (2010). Effects of early exposure and lifetime exposure to intimate partner violence on child adjustment. Violence & Victims, 25(4),427-439. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.427 [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann, S. A., & Miller, L. E. (2013). Intervention to reduce traumatic stress following intimate partner violence: An efficacy trial of the Moms' Empowerment Program (MEP). Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 41(2)329-350. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2013.41.2.329 [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann, S. A., & Miller-Graf, L. (2015). Community-Based Intervention for Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A randomized control trial. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(4),537-547. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000091 [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Howell, K. H., Lilly, M., & DeVoe, E. (2011). Mediators and moderators of change in adjustment following intervention for children exposed to intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(9)1815-1833. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510372931 [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Lynch, S., Banyard, V., De Voe, E. R., & Halabu, H. (2007). Community-Based Intervention for Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: An efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(2),199-209. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.199 [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Miller-Graff, L. E., Howell, K. H., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2015). An Efficacy Trial of an Intervention Program for Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 152(6),1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0532-4 [ Links ]

Grip, K., Almqvist, Axberg, U., & Broberg, A.G. (2013). Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence and the Reported Effects of Psychosocial Interventions. Violence and Victims, 28(4),635-655. http://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00012 [ Links ]

Grip, K., Almqvist, K., & Broberg A. G. (2011). Effects of a Group-Based Intervention on Psychological Health and Perceived Parenting Capacity among Mothers Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence (IPV): A Preliminary Study. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 81(1),81-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377317.2011.543047 [ Links ]

Grip, K., Almqvist, K., & Broberg, A. G. (2012). Maternal report on child outcome after a community-based program following intimate partner violence. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 66,239-247. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2011.624632 [ Links ]

Harris, K. E. (2017). Helping children exposed to violence at home: An essentials guide. London Family Court Clinic. [ Links ]

Holmes, M. R. (2013). The sleeper effect of intimate partner violence exposure: Long-term consequences on young children's aggressive behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(9),986-995. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12071 [ Links ]

Howarth, E., Moore, T. H., Welton, N. J., Lewis, N., Stanley, N., MacMillan, H., Shaw, A., Hester, M., Bryden. P., & Feder, G. (2016). Improving Outcomes for children exposed to domestic violence (IMPROVE): An evidence synthesis. Public Health Research, 4(10). https://doi.org/10.3310/phr04100 [ Links ]

Humphreys, C. (2007). Domestic violence and child protection: Challenging directions for practice. Issues paper no. 13. Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse. http://www.austdvclearinghouse.unsw.edu.au/PDF%20files/IssuesPaper_13.pdf [ Links ]

Katz, E. (2014). Strengthening mother-child relationships as part of domestic violence eecovery. Centre for research on families and relationships. www.crfr.ac.uk [ Links ]

Katz, E. (2015). Domestic violence, children's agency and mother-child relationships: Towards a more advanced model. Children & Society, 29,69-79. [ Links ]

Kistin, C., & Bair-Merritt, M. H. (2017). Child witness to violence. In International Encyclopedia of Public Health (pp. 513-516). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803678-5.00064-3 [ Links ]

Levendosky, A. A., Leahy, K. L., Bogat, G. A., Davidson, W. S., & von Eye, A. (2006). Domestic violence, maternal parenting, maternal mental health, and infant externalizing behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(4),544-552. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.544 [ Links ]

Lutwak, N. (2018). The Psychology of Health and Illness: The Mental Health and Physiological Effects of Intimate Partner Violence on Women. The Journal of Psychology, 152(6),373-387. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1447435 [ Links ]

Marshall, L. L. (1992). Development of the Severity of Violence Against Women Scales. Journal of Family Violence, 7(2),103-121. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00978700 [ Links ]

McWhirter, P. T. (2011). Differential Therapeutic Outcomes of Community-Based Group Interventions for Women and Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(12)2457-2482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510383026 [ Links ]

Menon, S. V., Cohen, J. R., Shorey, R. C., & Temple, J. R. (2018). The Impact of Intimate Partner Violence Exposure in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: A Developmental Psychopathology Approach. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47,1- 12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1437736 [ Links ]

Miller, N. E. (2015). The actions and perceptions of mothers who have experienced domestic violence. [Unpublished Doctoral Thesis]. California State University. [ Links ]

Moffitt, T. E. (2013). Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: Clinical intervention science and stress-biology research join forces. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt2),1619-1634. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000801 [ Links ]

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Med, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [ Links ]

Mohr, D. C., Spring, B., Freedland, K. E., Beckner, V., Arean, P., Hollon, S. D., Ockene, J., & Kaplan, R. (2009). The Selection and Design of Control Conditions for Randomized Controlled Trials of Psychological Interventions. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(5),275-284. https://doi.org/10.1159/000228248 [ Links ]

Overbeek, M. M., Clasien de Schipper, J., Lamers-Winkelman, F., & Schuengel, C. (2012). The effectiveness of a trauma-focused psychoeducational secondary prevention program for children exposed to interparental violence: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 13(12). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-12 [ Links ]

Overbeek, M. M., Clasien de Schipper, J., Lamers-Winkelman, F., & Schuengel, C. (2013). Effectiveness of specific factors in community-based intervention for child-witnesses of interparental violence: A randomized trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37,1202-1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.007 [ Links ]

Overbeek, M. M., Clasien de Schipper, J., Lamers-Winkelman, F., & Schuengel, C. (2014). Risk Factors as Moderators of Recovery During and After Interventions for Children Exposed to Interparental Violence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(3),295-306. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000007 [ Links ]

Overbeek, M. M., Clasien de Schipper, J., Lamers-Winkelman, F., & Schuengel, C. (2017). Mediators and Treatment Factors in Intervention for Children Exposed to Interparental Violence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(3),411-427. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1012720 [ Links ]

Patias, N. D., Bossi, T. J., & Del'Aglio, D. D. (2014). Repercussões da exposição à violência conjugal nas características emocionais dos filhos: Revisão sistemática da literatura. Temas em Psicologia, 22(4),901-915. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2014.4-17 [ Links ]

Pernebo, K., Fridell, M., & Almqvist, K. (2018). Outcomes of psychotherapeutic and psychoeducative group interventions for children exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79,213-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.02.014 [ Links ]

Pinto-Junior, A. A., & Tardivo, L. S. P. C. (Orgs.). (2017). Escala de Exposição à violência doméstica- EEDV. Vetor. [ Links ]

Shaughnessy, J. J., Zechmeister, E. B., & Zechmeister, J. S. (2012). Metodologia de pesquisa em Psicologia. AMGH Editora. [ Links ]

Silva, J. A. (2014). ACT: Uma possibilidade de prevenção universal à violência contra a criança. [Unpublished Master's Dissertation]. Universidade Federal de São Carlos. [ Links ]

Silva, J. M. M., Lima, M. C., & Lurdemir, A. B. (2017). Intimate partner violence and maternal educational practice. Rev Saúde Pública, 51(34),1-11. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1518-8787.2017051006848 [ Links ]

Stein, S. F., Grogan-Kaylor, A. C., Galano, M. M., Clark, H. M., & Graham-Bermann, S. A. (2018). Contributions to Depressed Affect in Latina Women: Examining the Effectiveness of the Moms' Empowerment Program. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518760005 [ Links ]

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (Ct) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41(1),75. https://doi.org/10.2307/351733 [ Links ]

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (Cts2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3),283-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251396017003001 [ Links ]

Timmer, S. G., Ware, L. M., Urquiza, A. J., & Zebell, N.M. (2010). The Effectiveness of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Victims of Interparental Violence. Violence and Victims, 25(4),486-503. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.486 [ Links ]

Visser, M. M., Telman, M. D., Clasien de Schipper, J., Lamers-Winkelman, F., Schuengel, C., & Finkenauer, C. (2015). The effects of parental components in a trauma-focused cognitive behavioral based therapy for children exposed to interparental violence: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 15(131),1-18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0533-7 [ Links ]

Walsh, F. (2016). Processos normativos da família: Diversidade e complexidade. Artmed. [ Links ]

Williams, L. C. A., Santini, P. M., & D'Affonseca, S. M. (2014). The Parceria Project: A Brazilian parenting program to mothers with a history of intimate partner violence. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 4(3),101-107. [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Global status report on violence prevention. WHO. [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). Global plan of action: health systems address violence against women and girls. WHO. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Sabrina Mazo D'Affonseca

Rua Nicola Bibo, 47, Residencial Samambaia

São Carlos, SP, Brazil. CEP 13565-510

E-mail: samazo@ufscar.br

Received: April 16th, 2020

Accepted: May 18th, 2021