Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

versão impressa ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. v.43 n.1 Porto Alegre abr. 2009

Assessment of the volunteer process model in environmental volunteers

Análisis del modelo del proceso del voluntariado en voluntarios ambientales

María Celeste Dávila1

Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

ABSTRACT

Most of the explanatory models of volunteerism have focused on the study of assistantial volunteerism and have not verified whether their results could be generalized to other types of volunteerism. The purpose of this work is to verify the validity of the Volunteer Process Model in environmental volunteers. Therefore, a field study of 140 environmental volunteers is presented in which the antecedents and experiences of volunteerism are used to predict duration of service over one year. In general, the results obtained indicate that this model does not explain sustained environmental volunteerism adequately.

Keywords: Organizational behavior; Prosocial behavior; Sustained volunteerism.

RESUMEN

La mayoría de los modelos explicativos del voluntariado se han centrado en el estudio del voluntariado asistencial y no se ha comprobado si estos modelos podrían ser generalizados a otros tipos de voluntariado. El propósito de este trabajo es analizar la validez del Modelo del Proceso del Voluntariado en voluntarios ambientales. Con este objetivo se llevó a cabo un estudio de campo en el que se evaluaron los antecedentes y las experiencias de voluntariado de 140 voluntarios ambientales para predecir su permanencia en la organización voluntaria a lo largo de un año. En general, los resultados obtenidos muestran que el modelo estudiado no explica adecuadamente la permanencia del voluntariado ambiental.

Palabras clave: Conducta organizacional; Conducta prosocial; Permanencia del voluntariado.

Volunteerism is a social phenomenon that consists basically of devoting time and work to various causes. In the last few years, its expansion and social acceptance have increased to such an extent that governments of very diverse states have assimilated it as an indispensable pillar to provide various services.

This kind of behavior is so important that its specific study has awakened the interest of social scientists. Psychosocial research has studied this phenomenon from various viewpoints. Thus, some investigations focus on the identification of the variables that differentiate volunteers from nonvolunteers in an attempt to clarify the determinants that lead an individual to decide to become a volunteer, whereas others attempt to identify effective predictors of sustained volunteerism (Clary & Snyder, 1991).

Many different variables have been analyzed, although not all have received the same attention. Smith (1994) carried out a bibliographic review between 1975 and 1992 and identified five categories of variables: (a) contextual variables (size of residential community, nature of the volunteer organization or group, etc.); (b) social background variables (education, gender, etc.); (c) personality variables (disposition to be helpful, extraversion, etc.); (d) attitudinal variables (sympathy for the group receiving the service, etc.); (e) situational variables (relations with other people, etc.).

Vecina (2001) included a sixth category: volunteer motivations, to which Smith (1994) only referred indirectly when describing the attitudinal variables.

Omoto and Snyder (2002) proposed other more exhaustive categories based on level of analysis (agency, individual volunteers, social system) and stages of the volunteer process (antecedents, experiences, consequences), but these categories can be gathered under Smith's categories.

Smith's (1994) review and Omoto and Snyder's (2002) categories showed that volunteerism is a multidetermined phenomenon and, given its complexity, theoretical models should be designed to organize the importance and relative influence of the determinants of its explanation. Penner (2004) proposed that a full understanding of sustained volunteering requires a consideration of situational, dispositional and structural variables and must have a temporal and dynamic component as well.

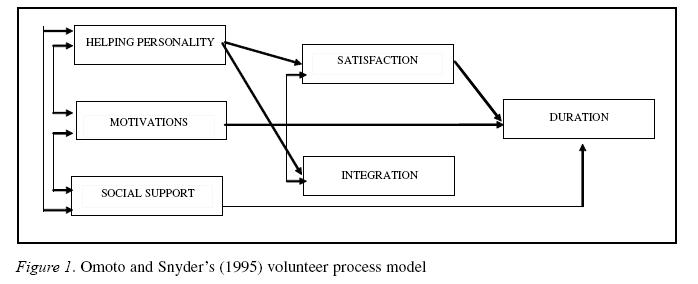

Towards the mid nineties, new explanatory models of initiation and development of volunteer activity began to be published. Despite the fact that there are other explanatory models, Omoto and Snyder's (1995) model is perhaps the most well known. This model covers the phases through which volunteers working with AIDS go and predicts the duration of their sustained volunteerism and the attitude change that comes about as a result of their activity. The authors distinguished three points in this process, and in each one, they identified a series of variables as determinants: (a) The antecedents of volunteer behavior provide information about the factors that lead people to become volunteers: disposition to be helpful (personality attributes), motivations and social support. The dispositional variables play a more important role because there are few situational restrictions in the initial decision to become a volunteer. In this sense, the model places special emphasis on motives and needs (Penner & Finkelstein, 1998). (b) Volunteerism experience refers to the experiences that may promote or deter continuing involvement. Omoto and Snyder (1995) focused on two factors: satisfaction with volunteer activity and organizational integration. (c) The consequences for the volunteers, the receivers, the organization and society in general were also taken into account by Omoto and Snyder (1995), although, in fact, they were only interested in predicting the following ones: Length of service as a volunteer and attitude change towards the target population of the intervention.

Upon testing their model (see Figure 1), they found that: motivation had a direct and positive influence on length of service, satisfaction was related to longer length of service, social support had a direct and negative relationship with longevity of service, and the helping disposition construct had a direct and positive influence on satisfaction and on organizational integration.

Subsequently, other theoretical models derived from Omoto and Snyder's model have been developed: The main contribution of Davis, Hall, and Meyer (2003) is the introduction of subjective experiences while volunteering; and the main contribution of Vecina (2001) is the integration of more psychosocial variables (organizational conflict and support, for example).

From another theoretic perspective, Piliavin and associates (Callero, Howard, & Piliavin, 1987; Grube & Piliavin, 1996; Piliavin & Callero, 1991) developed the Role Identity Model of Volunteerism. In this model, the concept of role identity is important to explain the continuity of volunteerism. Wilson and Musick (1997) presented a model in which both volunteering and informal helping are predicted from demographic variables and various types of capital (human capital, social capital and cultural capital).

Among the most recent models, we highlight the conceptual model of Penner (2004) of the initial decision to volunteer, or his conceptual model of sustained volunteerism (Penner, 2002), the innovative model of Hart, Atkins and Donnelly (2004, see Penner, Dovidio, Piliavin, & Schroeder, 2005), which attempts to integrate both sociological and psychological approaches to volunteering, and three-stage model of volunteer's duration of service (Chacón, Vecina, & Dávila, 2007) to explain the different factors that predict the duration of service over short or long periods of time.

In contrast, despite the differences there may be among the models developed up to the present, most of them were designed to explain sustained volunteerism in the socio-health area. In the research on volunteerism, very few studies have been carried out with other types of volunteerism, such as, for example, environmental volunteerism. From volunteerism's research in Spain, we highlight the basic model (Dávila & Chacón, 2004, 2007) to explain sustained volunteerism in any type of volunteerism.

Recent research has shown that socio-assistantial volunteers and environmental volunteers present statistically significant differences in very diverse variables that are relevant to sustained volunteerism (Dávila, 2003): motivations, organizational variables (activity characteristics, relationship with other volunteers and staff, organizational support, organizational conflict, economic costs derived from volunteer activity, supervision, training and incentives received), and organizational attitudes (satisfaction and job involvement). In addition, according to the cognitive typology developed by Chacón and Dávila (2001), people clearly differentiate environmental volunteerism and socio-assistantial volunteerism.

A review of studies of environmental volunteerism can be found in Martínez and McMullin (2004), and Rayan, Kaplan and Grese (2001).

According to these important differences observed, we wondered whether the models developed so far, models designed chiefly to account for socio-assistantial volunteerism, are useful to explain environmental volunteerism. The aim of the current study is to determine if Omoto and Snyder's (1995) model can be generalized to environmental volunteerism. The analysis will focus on the causal relationships.

Method

Participants

In this study, 140 volunteers belonging to 6 Spaniards nongovernmental environmental organizations participated.

The volunteers carried out various activities: project management, clerical jobs, document classification, medical treatment, bird census, territory observation, care of animals in shelters, restoration of shelters, reforestation jobs, and environmental education.

The sample was composed by 73.6% men and 26.4% women. Their ages ranged between 17 and 67 years, with a mean age of 33 years and a standard deviation of 8.5 years. Regarding educational level, 7.1% had elementary studies, 35% secondary studies, and 57.9% university studies.

Instruments

The following instruments were used to assess the constructs included in each of the explanatory models:

Disposition to be Helpful. To measure this construct, we used the Emotional Empathy Questionnaire (Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972), comprised of 33 items with a 9-point Likert-type response scale. The internal consistency reliability was 0.73.

Motivations. To study motivations that lead people to become volunteers, we used the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI) of Clary et al. (1998), adapted to the Spanish population and to environmental volunteerism by Dávila and Chacón (2003a, 2003b). This instrument consists of 30 items, to which participants respond on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 7 (extremely important). It includes 6 subscales: Protective, values, career, social, understanding, and enhancement. The total reliability of the scale was .92, and the reliability interval for the subscales was .61 - .90.

Organizational Commitment. Organizational commitment was assessed by the following measures: (a) Some questions and responses format used by Omoto and Snyder (1995) to measure the construct they called organizational integration: their acceptance of the philosophy, goals, and purposes of organization; their willingness to recruit new volunteers for the organization; and the extent to which they would like to take on additional assignments at the organization. (b) The reduced version of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) by Mowday, Steers, and Porter (1979), adapted to the Spanish population and volunteerism by Dávila and Chacón (2003a, 2003b). This questionnaire has 9 items with a 7-point Likert-type response format, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). The internal consistency reliability was 0.88.

The following variables were assessed by means of similar measurement instruments as those used in the original study by Omoto and Snyder (1995).

Social Support. The measures included were about perceived availability of support: (a) the degree of emotional support that he/she receives from people who know about his/her volunteer activity: family, friends, a partner, or fellow workers (evaluated on a 7-point scale); (b) the degree of general support for the development of the volunteer activity that he/she receives from signi-ficant others (evaluated on a 7-point scale)

Satisfaction. The volunteer's job satisfaction was evaluated by: (a) the respondents rated (1 = not at all, 7 = extremely) their experiences as volunteers on the following nine dimensions: Satisfying, rewarding, exci-ting, interesting, disappointing, enjoyable, challenging, important, boring; (b) volunteers also used a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to rate their agreement with a general satisfaction item ("Overall, I am satisfied with my experience as a volunteer").

Total Duration of Service. Omoto and Snyder (1995) assessed sustained volunteerism in the organization by adding the previous sustained service and the length of service during the follow-up periods.

Whenever possible, we used the same instruments as those originally employed, but in some cases, we decided that other instruments were better adapted to the requirements of the present study or that they would improve the prediction of the theoretical constructs.

Procedure

The conditions of the questionnaire administration were agreed upon with each organization to cause the least possible interference in its habitual functioning.

In some cases, a representative of the organization distributed the questionnaires and collected them later on. In other cases, the representative provided a list of the volunteers' addresses, so we could send them the questionnaire along with a prepaid envelope for its return. Lastly, in other cases, the representative took charge of sending the questionnaire by e-mail to the volunteers, to be returned either by normal mail, e-mail, or fax to the organization representative or to the research representative.

Although these different data collection procedures could have potentially affected the volunteers' responses, we sought to keep collaboration rates as high as possible by adjusting to the requirements of the organizations.

After collecting the measurements, two telephone follow-ups were carried out to determine whether volunteers remained in the NGO: at 6 months and at 12 months.

Thus, out of the 140 volunteers who constituted the sample: (a) at the first follow-up, 22 volunteers had dropped out of the organization; (b) at the second follow-up, 4 volunteers had dropped out.

Data Analysis

To verify the predictive power of Omoto and Snyder's (1995) model in environmental volunteers, structural equation models were employed (AMOS 4.0 computer program).

Results

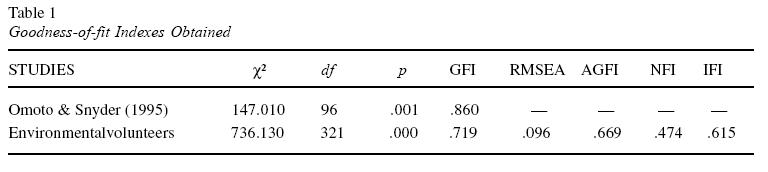

The goodness-of-fit indexes obtained for the model of Omoto and Snyder (1995) in the sample of environmental volunteers are shown in Table 1.

Omoto and Snyder's (1995) model is graphically represented in Figure 2, as well as the standardized regression weights of the most important relationships and the percentages of explained variance of each construct. In addition, the observed variables that were used for the configuration of the constructs can also be examined.

In Omoto and Snyder's (1995) model, c²(321, N = 140) = 736.130, p = .000, so it can be assumed that the differences between the effective and the foreseen matrixes were significant, and, therefore, the fit of the model is not acceptable (see Table 1).

When reviewing other absolute goodness-of-fit indexes (GFI, RMSEA), and indexes of incremental fit (AGFI, NFI, IFI) for Omoto and Snyder's (1995) model, we found that none of them presented values that could be considered acceptable (see Table 1). GFI, AGFI, NFI and IFI have a range of 0.0 to 1.0, with values closer to 1.0 indicating better fitting models. RMSEA with a value of 0.0 indicates that the model exactly fits the data, but values between 0.0-0.08 are considered acceptable (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1999).

The regression weights and explained variance shown in Figure 2 confirm the poor fit of the model in environmental volunteers. The only relationships hypothesized by the model that were significant were between empathy and satisfaction (CR = coefficient/SE= 3.797, p < .05), and between empathy and organizational integration (CR= 2.324, p < .05). None of the remaining hypothesized relationships was significant. Moreover, the percentages of explained variance of each construct were low, and not even 7% of the variance of the total duration of sustained volunteerism was accounted for.

Discussion

In general, the results obtained show that Omoto and Snyder's (1995) model does not explain sustained environmental volunteerism adequately. The fit to the empirical data cannot be considered acceptable, the percentages of explained variance of satisfaction, integration, and total duration of service are very low, and some relationships between constructs are not significant.

Motivations had a positive influence on service duration, but it was not significant; satisfaction was related to longer service duration, but it was neither positive nor significant; and social support had a direct and negative relationship with service duration, but it was not significant. Ultimately, the only significant relationships were between empathy (concerning the helping disposition construct) and satisfaction, and between empathy and organizational integration.

The lack of support for the model confirms that it cannot be generalized to another type of volunteerism. However, the results found do not question the validity of the model for AIDS volunteerism, as the model was developed for this type of volunteerism. In the study by Omoto and Snyder (1995), the volunteers carried out activities involving a high emotional demand, and, obviously, the environmental sample performed activities that differ enormously from those of the former study. Thus, the poor fit of the former model may be due to the fact that it was designed and adapted to volunteers with certain characteristics not shared by those who partici-pated in this present research.

The lack of support for the model may also be par-tially due to differences in the methodology employed to collect the data and to the specification of the variables observed in the model, as well as cultural diffe-rences. The most important differences are described more extensively in the following paragraphs.

Some of the variables observed included by Omoto and Snyder (1995) to determine latent constructs could not be included in the current study, either because it was impossible to find measurements with appropriate psychometric qualities or because, when using some of these measurements, unacceptable estimations were obtained that invalidated the analyses of the data. In the case of motivations, a more up-to-date instrument was used (Clary et al., 1998).

Moreover, we had to select instruments that were easily adaptable to environmental volunteerism, because practically all the instruments used in the study of volunteerism are designed to assess socio-assistantial volunteerism, and in some cases, we had to add other measures for the best prediction of the constructs, as in the case of organizational integration.

In addition, the procedure used to gather data was slightly different from those used in the original research. Omoto and Snyder (1995) combined information from volunteers' self-reports and from agency records to carry out the follow-ups. Also, in the current study, the total follow-up had a 1-year duration, whereas in the former study, it lasted 2½ years.

Lastly, it should be remembered that this study focused on the analysis of causal relationships, and this may have reduced the explanatory capacity of the model, because covariate relationships were not included. But we think that the general results would not be very different if theses relationships had been taken into account.

The results indicate the need for the study of volunteerism to be sufficiently sensitive to the peculiarities of each type of volunteerism and, hence, to the risk of overgeneralization of some findings. Specifically, not only the differences observed in the fit of the explanatory model, but also the lower percentages of explained variance reveal the idiosyncrasy of environmental volunteerism.

We also would like to emphasize the need to study environmental volunteerism and to design models that explain the permanence of this type of volunteers. The number of environmental volunteers and the number of environmental organizations have increased exponentially in the last years, and the psychosocial studies of environmental volunteerism are still relatively few.

References

Callero, P., Howard, J. A., & Piliavin, J. A. (1987). Helping behaviour as role behaviour: Disclosing social structure and history in the analysis of prosocial action. Social Psychology Quarterly, 50(3), 247-256. [ Links ]

Chacón, F., & Dávila, M. C. (2001). Construcción de una tipología cognitiva sobre actividades de voluntariado. Psicología Social Aplicada, 12(2), 35-59. [ Links ]

Chacón, F., Vecina, M. L., & Dávila, M. C. (2007). The three-stage model of volunteers' duration of service. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 35(5), 627-642. [ Links ]

Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1991). A functional analysis of altruism and prosocial behavior: The case of volunteerism. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 12, 119-148. [ Links ]

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516-1530. [ Links ]

Dávila, M. C. (2003). La incidencia diferencial de los factores psicosociales en distintos tipos de voluntariado. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain. [ Links ]

Dávila, M. C., & Chacón, F. (2003a). Adaptación de instrumentos para la evaluación de aspectos organizacionales en ONG´s. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 19(2), 159-179. [ Links ]

Dávila, M. C., & Chacón, F. (2003b). Adaptación del inventario de funciones del voluntariado a una muestra española. Encuentros en Psicología Social, 1(2), 22-26. [ Links ]

Dávila, M. C., & Chacón, F. (2004). Factores psicosociales y tipo de voluntariado. Psicothema, 16(4), 639-645. [ Links ]

Dávila, M. C., & Chacón, F. (2007). Prediction of longevity of volunteer service: A basic alternative proposal. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(1), 115-121. [ Links ]

Davis, M. H., Hall, J. A., & Meyer, M. (2003). The first year: Influences on the satisfaction, involvement and persistence of new community volunteers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(2), 248-260. [ Links ]

Grube, J., & Piliavin, J. A. (1996). Role-identity, organizational commitment, and volunteer performance. Paper presented at the annual meeting of Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, Miami, FL. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1999). Análisis multivariante. Madrid, Spain: Prentice Hall Iberia. [ Links ]

Martínez, T. A., & McMullin, S. L. (2004). Factors affecting decisions to volunteer in nongovernmental organizations. Environmental and Behavior, 36(1), 112-126. [ Links ]

Mehrabian, A., & Epstein, N. (1972). A measure of emotional empathy. Journal of Personality, 40(4), 525-543. [ Links ]

Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14, 224-247. [ Links ]

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 671-686. [ Links ]

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (2002). Considerations of community. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 846-867. [ Links ]

Penner, L. A. (2002). Dispositional and organizational influences on sustained volunteerism: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 447-467. [ Links ]

Penner, L. A. (2004). Volunteerism and social problems: Making things better or worse?. Journal of Social Issues, 60(3), 645-666. [ Links ]

Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., & Schroeder, D. A. (2005). Prosocial behaviour: Multilevel perspectives. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 365-392. [ Links ]

Penner, L. A., & Finkelstein, M. A. (1998). Dispositional and structural determinants of volunteerism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 525-537. [ Links ]

Piliavin, J. A., & Callero, P. L. (1991). Giving blood: The development of an altruistic identity. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Rayan, R. L., Kaplan, R., & Grese, R. E. (2001). Predicting volunteer commitment in environmental stewardship programmes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 44(5), 629-648. [ Links ]

Smith, D. H. (1994). Determinants of voluntary association participation and volunteering: A literature review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 23(3), 243-263. [ Links ]

Vecina, M. L. (2001). Factores psicosociales que influyen en la permanencia del voluntariado. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain. [ Links ]

Wilson, J., & Musick, M. (1997). Who cares? Toward an integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review, 62, 694-713. [ Links ]

Received 03/12/2007

Accepted 04/09/2008

Maria Celeste Dávila. Ph.D. in Psychology and lecturer in Complutense University of Madrid, Spain.

1 Address: Complutense University of Madrid, Social Psychology Department, Faculty of Political Science and Sociology, Campus de Somosaguas, s/n, Madrid, Spain, 28223. Phone: +34 91 394 27 66; Fax: +34 91 394 30 29. E-mail: mcdavila@cps.ucm.es.