Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

versão impressa ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. vol.43 no.3 Porto Alegre dez. 2009

A capital sin: dispositional envy and its relations to wellbeing

Um pecado capital: inveja disposicional e suas relações com o bem-estar

Taciano L. Milfont1I-II; Valdiney V. GouveiaIII

ICentre for Applied Cross-Cultural Research, Wellington, New Zealand

IIVictoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

IIIFederal University of Paraiba, Joao Pessoa, Brasil

ABSTRACT

Envy is a pancultural emotion felt by most individuals during their lifetime. The Dispositional Envy Scale (DES) is a 8-item self-reported measure developed to assess people’s tendencies to feel envy. This study first examines the reliability and validity of the DES in measuring envy in a Brazilian sample, and then the relationship between envy and wellbeing. The DES had acceptable reliability (internal consistency and homogeneity) as well as factorial and criterion-related validity. As expected, envy was negatively related to wellbeing measures (life satisfaction, vitality, and happiness), indicating that an envy-prone person is more likely to have low feelings of aliveness and energy, and to express unhappiness with their lives. The findings support the psychometric properties of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the DES, and also highlight the potential impact of envy on people’s wellbeing.

Keywords: Envy; Wellbeing; Dispositional Envy Scale; Validity; Reliability.

RESUMO

Inveja é uma emoção pancultural vivenciada pela maioria das pessoas durante suas vidas. A Escala de Inveja Disposicional (Dispositional Envy Scale, DES) foi desenvolvida para avaliar a tendência de as pessoas sentirem inveja. O presente estudo primeiramente avalia a validade e a confiabilidade da DES para medir inveja em uma amostra brasileira, e depois examina as relações entre inveja e bem-estar. A DES apresentou confiabilidade aceitável (consistência interna e homogeneidade) bem como validade fatorial e de critério. Como esperado, inveja disposicional foi negativamente correlacionada com medidas de bem-estar (satisfação com a vida, vitalidade e felicidade), indicando que pessoas que tendem a sentir inveja são mais prováveis a apresentar menos vidalidade e energia, assim como expressar infelicidade em suas vidas. Os resultados suportam as propriedades psicométricas da versão brasileira da DES, além de destacar o impacto potencial da inveja no bem-estar das pessoas.

Palavras-chave: Inveja; Bem-estar; Escala de Inveja Disposicional; Validade, Confiabilidade.

“Envy is the ulcer of the soul”

(Socrates, 469-399 BC).

Research has shown that envy is found across cultures and felt by most individuals (Schoeck, 1969; Smith, Parrot, Diener, Hoyle, & Kim, 1999). Envy refers to the feelings aroused when one person desires what someone else has (Smith et al., 1999), and thus occurs when two individuals express mutual comparison (Schoeck, 1969). Although envy is sometimes confused with jealousy – and situations creating jealousy also tend to create envy – these two emotions can be theoretically and empirically distinguished (Epstein, 2006; Parrot & Smith, 1993). Differently from envy, jealously always involves three people and refers to the feelings aroused when one person is suspicious of rivals or fears losing a special relationship to another person (Parrot & Smith, 1993; Smith et al., 1999). The present study examines dispositional envy and its relations to wellbeing in a Brazilian sample.

Measuring Dispositional Envy

There are two principal affective components of envy: hostile and depressive components (Smith, Parrot, Ozer, & Moniz, 1994). The hostile component is associated with feelings of ill will and anger that result from subjective injustice beliefs. The depressive component is associated with feelings of inferiority that result from unfavourable social comparison. Therefore, hostile and depressive feelings in envy are respectively linked to the envying person’s subjective belief that the envied person’s advantage is unfair, and to the envying person’s sense of inferiority. Hence, people who are envy-prone (i.e., people with high dispositional envy) are likely to (a) be susceptible to frustration and subjective sense of injustice, and to (b) interpret upward social comparison as revealing inferiority (Smith et al., 1999; Smith et al., 1994). Independent research has also provide support for the link between envy and feelings of inferiority and ill will by showing that experienced familial injustice and relational imbalances enhances the development of envy (Luglio, 2002).

The Dispositional Envy Scale (DES) is a 8-item self-reported measure developed to assess tendencies to feel envy (Smith et al., 1999). The validity and reliability of the DES was assessed in several samples in the U.S. The item-total correlations ranged from .48 to .71; the alphas ranged from .83 to .86; the 2 weeks test-retest reliability was .80; and the DES showed a moderate correlation (r = –.32, p < .01) with social desirability. Although three different factor structure models (i.e., one-factor, two-factor, and bifactor models) were assessed by confirmatory factor analysis, results from both exploratory and confirmatory factors analysis indicate that the items of the DES represent a single construct.

Dispositional Envy and Wellbeing

The validity of the DES was supported by correlations with other individual differences measures. The DES was positively associated with measures linked to both inferiority (e.g., low self-esteem, depression, neuroticism, jealously) and ill will (e.g., hostility, resentment), and negatively associated with measures of wellbeing (e.g., life satisfaction, happiness) (Smith et al., 1999). Specifically, Smith et al. (1999) found that dispositional envy was strongly and negati-vely related to life satisfaction across three different samples (rmean = –.38). Similarly, dispositional envy was strongly and negatively related to an overall happiness index (r = –.35), and also to the percentage of time that participants feel unhappy (r = –.25). Dispositional envy has also been found to be positively associated with maternal grief (Barr & Cacciatore, 2007), masochism and covert narcissism (Luglio, 2002), and interpersonal counterproductive work behaviour - behaviours aimed at inflicting personal harm on another (Cohen-Charash & Mueller, 2007). Dispositional envy has also been observed to be negatively associated with gratitude (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002), and to be associated with higher levels of dispositional shame and lower levels of overall self-esteem (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007). These findings clearly indicate the link between dispositional envy and illbeing. Therefore, a negative association between the DES and wellbeing measures is expected.

The Present Study

The findings reviewed above support the reliability and validity of the DES, and also indicate that a dispositionally envious person is more likely to have low self-esteem, to feel depressed, and to express unhappiness with their lives. Although the psychometric property of the DES has been demonstrated, not many other studies have used this measure since its publication nearly ten years ago (Barr & Cacciatore, 2007; Luglio, 2002; McCullough et al., 2002; Parks, Rumble, & Posey, 2002; Sawada & Arai, 2002). This lack of empirical studies using the DES seems to be a result of resear-chers’ focus on theoretical considerations of envy (e.g., Smith & Kim, 2007) rather than a focus on empirical research. The present study addresses this lack of empirical studies by examining the validity and reliability of the DES for measuring dispositional envy in another cultural context. Specifically, this study examines the reliability, construct validity, and criterion- related validity of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the DES. Another aim of this study is to examine whether the relationship between dispositional envy and wellbeing holds in the Brazilian context.

Method

Participants and Instruments

A total of 102 undergraduate students participated in the study. Their ages ranged from 17 to 40 (M = 22, SD = 4.55), and 74% were female. In addition to the DES, participants completed the Satisfaction With Life Scale ([SWLS]; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985; Gouveia, Milfont, Fonseca, & Coelho, 2009), the subjective vitality scale (Ryan & Frederick, 1997), and a single self-report happiness item (on a 7-point scale anchored by extremely unhappy and extremely happy).

Procedure and Data Analyses

The questionnaire was administered during class. The students were informed about the objectives, anonymity and confidentiality of the study. The reliability of the measures was examined in relation to the instrument’s internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients) and homogeneity (mean inter-item correlations). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .70 or higher and mean inter-item correlations in the .20 to .40 range were deemed to indicate good reliability (Clark & Watson, 1995; Nunnally, 1978). Criterion-related validity was assessed by examining the correlations between DES and wellbeing measures.

Construct validity of the DES was assessed through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Exploratory factor analysis was performed using principal axis factoring, and confirmatory factor analysis was performed using LISREL and maximum-likelihood estimation procedures, taking the observed covariance matrix as the input. The degree to which the data fit the confirmatory models was assessed using the ratio of the Chi-square statistic to the degrees of freedom (χ2/df), the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Models with a χ2/df ratio in the range of 2 to 3, and CFI, RMSEA and SRMR with values respectively close to .95, .06 and .08 or better indicate acceptable fit (Carmines & McIver, 1981; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Reliability

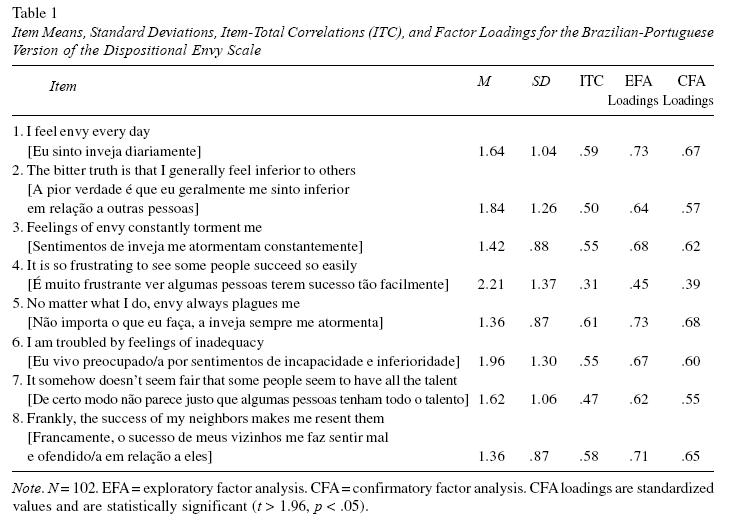

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and reliabilities for each of the DES items. The factor loadings ranged from .45 to .73, item means from 1.36 to 2.21, and item-total correlations from .31 to .59. The coefficient alpha in the present study was .79, which is not significantly lower (van de Vijver & Leung, 1997) than the lower coefficient (.83) reported in the original study. The results thus suggest that each item is reliably correlated with the whole scale, and that the DES has high internal consistency.

Construct Validity

Results from the exploratory factor analysis indicated that two eigenvalues were higher than one (3.48 and 1.22). However, the scree plot indicated a substantial drop after the first eigenvalue, and parallel analysis (Horn, 1965) also indicated that only the first eigenvalue was higher than those that would be obtained from 100 replications of random data with the same number of items and the same sample size (Fabrigar, MacCallum, Wegener, & Strahan, 1999; Watkins, 2000). This therefore suggests that only one factor should be extracted, which explained 43.5% of the total variance.

Taking into account Smith et al.’s (1999) findings as well as the results discussed above, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to evaluate the fit indices of the one-factor model of the DES. All loadings were statistically significant and ranged from .39 to .68 (see Table 1), but the indices indicated poor fit to the data: χ2 (20, N = 102) = 73.15, p < .001; χ2/df = 3.66; CFI = .85; RMSEA = .16 (90%CI = .12-.20); SRMR = .093. Inspection of the modification indices indicated that items 2 and 6, and items 7 and 8 share common error variance. Because items 7 and 8 were also found to share common variance in other samples (Smith et al., 1999), this provided empirical support for modifying the confirmatory model. Allowing the errors from this pair of items to correlate, the indices indicate a better fit to the data: χ2 (19, N = 102) = 53.97, p < .001; χ2/df = 2.84; CFI = .90; RMSEA = .13 (90%CI = .093-.18); SRMR = .080. These results suggest that the unidimensional factor structure of the DES is also adequate in this sample.

Criterion-Related Validity

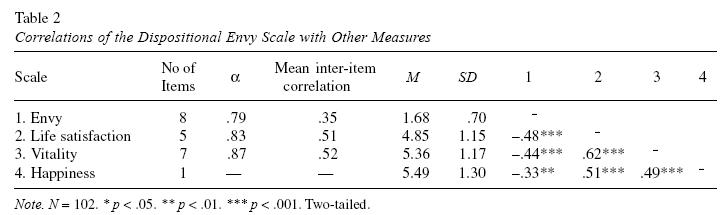

Correlations between the DES and wellbeing measures were performed and are shown in Table 2. In line with predictions, the DES was negatively correlated to all three wellbeing measures, and the correlations were moderate to high in terms of effect size (Hemphill, 2003). This indicates that tendencies to feel envy are negatively associated to life satisfaction, vitality, and happiness.

Discussion

Envy is a pancultural emotion and thus felt by most individuals (Epstein, 2006; Schoeck, 1969). Envy is a result of subjective injustice beliefs and unfavourable social comparisons. Injustice beliefs and social comparisons lead respectively to feelings of ill will and feelings of inferiority, which form the hostile and depressive affective components of envy (Parrot & Smith, 1993; Smith et al., 1999). Smith et al. (1999) developed the Dispositional Envy Scale (DES) to assess tendencies to feel envy, demonstrating the validity and reliability of this measure in U.S. samples.

The present study contributed to the effort of assessing tendencies to feel envy by testing the validity and reliability of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the DES. The results showed that the DES has high internal consistency and form a unidimensional factor structure. More importantly, the present study confirmed the negative relationship between envy and wellbeing. These results are in line with previous findings (Smith et al., 1999), indicating that the DES had acceptable internal reliability, criterion-related validity and construct validity in Brazil. Also in line with previous findings (Barr & Cacciatore, 2007; Luglio, 2002; Smith et al., 1999), the present results showed that a dispositionally envious person is more likely to be unhappy and dissatisfied with their lives, and to have low feelings of aliveness and energy. Thus, tendencies to fell envy should be reduced if one seeks wellbeing.

Future studies should further examine the shared variance between items 7 and 8; this might indicate that these items share content overlap because are related to subjective feelings of injustice formed by another person’s achievements (Smith et al., 1999). Future studies should also further validate the DES by assessing its reliability and validity across diverse samples. The sample considered here was small in size, the gender distribution was uneven (74% female), and was composed only by undergraduate students. Given that the DES is a short measure, it could be used to assess envy in diverse samples and in large cross-cultural projects. Using the DES in diverse and crosscultural samples would allow future studies to test the measurement invariance (e.g., Milfont, Duckitt, & Cameron, 2006) of the DES across age, gender, and cultural groups. Although research has indicated that envy is found across cultures and felt by most individuals, only a systematic cross-cultural project would provide strong empirical support for this pancultural quality of envy.

References

Barr, P., & Cacciatore, J. (2007). Problematic emotions and maternal grief. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 56, 331-348. [ Links ]

Carmines, E. G., & McIver, J. D. (1981). Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In G. W. Bohinstedt & E. F. Borgatta (Eds.), Social measurement: Current issues (pp. 65-115). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7, 309-319. [ Links ]

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Mueller, J. S. (2007). Does perceived unfairness exacerbate or mitigate interpersonal counterproductive work behaviors related to envy? Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 666-680. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. [ Links ]

Epstein, J. (2006). Envy: The seven deadly sins. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Fabrigar, L. R., MacCallum, R. C., Wegener, D. T., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4, 272-299. [ Links ]

Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., Fonseca, P. N., & Coelho, J. A. P. M. (2009). Life satisfaction in Brazil: Testing the psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) in five Brazilian samples. Social Indicators Research, 90, 267-277. [ Links ]

Hemphill, J. F. (2003). Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. American Psychologist, 58, 78-80. [ Links ]

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and technique for estimating the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179-185. [ Links ]

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. [ Links ]

Luglio, C. L. (2002). The mediating role of personality in the association between relational ethics and dispositional envy (Doctoral dissertation, Georgia State University, 2002). Dissertation Abstracts International, 63(6-B), 301. [ Links ]

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J.-A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112-127. [ Links ]

Milfont, T. L., Duckitt, J., & Cameron, L. D. (2006). A cross-cultural study of environmental motive concerns and their implications for proenvironmental behavior. Environment and Behavior, 38, 745-767. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Parks, C. D., Rumble, A. C., & Posey, D. C. (2002). The effects of envy on reciprocation in a social dilemma. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 509-520. [ Links ]

Parrot, W. G., & Smith, R. H. (1993). Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 906-920. [ Links ]

Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. (1997). On the energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65, 529-565. [ Links ]

Sawada, M., & Arai, K. (2002). Dispositional envy, domain importance, and obtainability of desired objects: Selection of strategies for coping with envy. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology, 50, 246-256. [ Links ]

Schoeck, H. (1969). Envy: A theory of social behavior. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World. [ Links ]

Smith, R. H., & Kim, S. H. (2007). Comprehending envy. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 46-64. [ Links ]

Smith, R. H., Parrot, W. G., Diener, E., Hoyle, R. H., & Kim, S. H. (1999). Dispositional envy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 1007-1020. [ Links ]

Smith, R. H., Parrot, W. G., Ozer, D., & Moniz, A. (1994). Subjective injustice and inferiority as predictors of hostile and depressive feelings in envy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 705-711. [ Links ]

van de Vijver, F., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Watkins, M. W. (2000). Monte Carlo PCA for parallel analysis [Computer software]. State College, PA: Ed & Psych. [ Links ]

Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 3-18. [ Links ]

Received 30/07/2008

Accepted 15/03/2009

Taciano L. Milfont. Centre for Applied Cross-Cultural Research and Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Valdiney V. Gouveia. Federal University of Paraiba, João Pessoa, Brazil.

1 Address: Victoria University of Wellington, School of Psychology, Centre for Applied Cross-Cultural Research, PO Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand 6140. Tel.: +64 4 463 6398. Fax: +64 4 463 5402. E-mail: milfont@gmail.com

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI