Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.23 no.2 São Paulo maio/ago. 2021

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPPE13553

ARTICLES

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION

Effects of social skills training on school climate

Efectos de la capacitación en habilidades sociales sobre el clima escolar

Giselle Glória Balbino dos SantosI ; Adriana Benevides SoaresI,II

; Adriana Benevides SoaresI,II ; Rafael V. S. BastosII

; Rafael V. S. BastosII

ISalgado de Oliveira University (Universo), Niterói, RJ, Brazil

IISão Francisco University (USF), São Paulo, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Studies point out that the development of social skills can interfere in the students' behavior and consequently in the environment, favoring the school climate and the acquisition of knowledge. Thus, this research aimed to identify the effects of a Social Skills Training (SST) on the school climate. 21 students from the 9th grade of Elementary School participated (11 from the Experimental group and 10 from the Control group) aged between 14 and 16 years old (MD = 14.38; SD = 1.07). The instruments used were: Inventory of Social Skills for Adolescents and the Climate Scale of the Delaware Student School. Ten sessions were held, with weekly meetings of 50 minutes. For data analysis, the following tests were used: Spearman's rô, Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney for independent samples. There were positive correlations, from moderate to strong, between the factors of social skills and the dimensions of the climate for all participants in the intervention group. In the control group, negative and positive correlations were identified.

Keywords: social skills; school climate; SST; students; elementary school.

RESUMEN

Los estúdios señalan que el desarrollo de habilidades sociales puede interferir em el comportamiento de los estudiantes y consecuentemente em el entorno, favoreciendo el clima escolar y la adquisición de conocimientos. Por lo tanto, esta investigación tuvo como objetivo identificar los efectos de un Entrenamiento de habilidades sociales (EHS) en el clima escolar. Participaron 21 alumnos de 9º de primaria (11 del grupo experimental y diez del grupo control) con edades comprendidas entre 14 y 16 años (DM = 14,38; DT = 1,07). Los instrumentos utilizados fueron: Inventario de Habilidades Sociales para Adolescentes y Escala de Clima de la Escuela de Delaware-Estudiantes. Se realizaron diez sesiones, con reuniones semanales de 50 minutos. Para el análisis de los datos se utilizaron las pruebas: rô de Spearman, Wilcoxon y Mann-Whitney para muestras independientes. Hubo correlaciones positivas de moderadas a fuertes entre los factores de habilidades sociales y las dimensiones del clima para todos los participantes en el grupo de intervención. Em el grupo de control se identificaron correlaciones negativas y positivas.

Palabras clave: habilidades sociales; clima escolar; EHS; estudiantes; enseñanza fundamental.

1. Introduction

Various authors have carried out studies focused on comprehending and developing the school climate (Bear et al., 2016; Cornejo & Redondo, 2001; Yang, Chang, & Ma, 2020), as its quality can be improved through interventions (Vinha et al., 2016). According to Vinha et al. (2016), to perform a consistent analysis of the climate it is initially necessary to identify a shared need in the school. The members of the school community have to adhere to the process and be willing to get involved in the projects in the short, medium and long term. School improvement requires coordinated, sustained action and intentional efforts to promote learning climates that provide for the socio-moral, emotional and intellectual development of the students. Therefore, the reform of the school climate is based on four overlapping central objectives that promote respect in the school: the creation of democratic communities, the promotion of support for students and teachers, the guarantee of a safe school and the encouragement of student participation. According to Treviño (2010), the school climate can be improved when you have good relationships among colleagues and teachers, a sense of belonging, similarity and peace of mind in the relationships with peers. There is no consensus in the literature on the definition of school climate. The school climate concept used here was defined as "the perception of individuals (students, parents, teachers/employees) regarding the quality and consistency of personal interactions that involve the school community" (Haynes, Emmons, & Ben-Avie, 1997, p. 322). This concept covers different dimensions, such as: learning, social relationships, safety, justice, participation, infrastructure and belonging. It is emphasized that, in order to obtain knowledge about the school climate, it is necessary to investigate the set of perceptions of the members in relation to the institution, which can provide the school with an opportunity to expand its knowledge in order to develop intervention proposals (Colombo, 2018). Furthermore, the quality of school life and the well-being of students are related to the school climate, this being a central concept for planning and implementing strategies that can promote the improvement of the school environment (Vinha et al., 2016).

The students' perception of the school climate was investigated by Vinha et al. (2018). They sought to identify differences between the institutions studied and the dimensions of the climate that were perceived as positive, negative or neutral. To carry out the study, a questionnaire with the ability to assess the school climate was prepared and applied to 566 students from the 7th to the 9th grade of four public schools, with additional observations carried out in two of these schools. The main results identified were that, in general, the students' perceptions about the school climate were divided between neutral (47.6%) and positive (48.1%) positions, with only 4.3% considered negative. The dimensions observed as the most positive were associated with intimidation among students, with rules, with social relations and with conflicts. The dimensions considered less positive were: the school's relations with the family and the infrastructure.

Another study developed by Vinha et al. (2016) aimed to construct and test instruments to assess the school climate in students, teachers and managers, as well as to design and develop an intervention project in two public elementary schools seeking to improve coexistence. After the diagnosis of the climate of these schools, the intervention was carried out in the following stages: inclusion of a weekly subject in the students' timetable; implementation of procedures for conflict mediation; proposals for youth protagonism and continued training of the school professionals. For the evaluation of the program, a qualitative analysis was performed through triangulation of the data collected using a semi-structured questionnaire applied with the professionals who were involved in this study. The results provided theoretical support and evidenced the validity of collectively studying and planning the coexistence at school, discussing the main challenges and the best intervention proposals.

Yang et al. (2020) conducted an investigation to verify the relationship between students' perceptions of four essential socio-emotional learning competencies (responsible decision-making, social awareness, self-management, and relationship skills), school climate and their experiences with bullying victimization. The multilevel moderating effects of students' perceptions of school climate, gender and school levels (elementary and high school) in the association between socio-emotional learning competencies and bullying victimization were also analyzed. Study participants were 23,532 students (4th to 12th grade) from 90 schools in Delaware, USA. The results showed that three of the four essential socio-emotional learning competences (i.e., social awareness, relationship skills and self-management) and perceptions of the school climate at the student level had significant associations with student's experiences of bullying victimization. Furthermore, a positive association was observed between social awareness and bullying victimization and a negative association between self-management and bullying victimization; both were mitigated in schools in which the students' perception of the school climate was more positive. The association between some of the socio-emotional learning competencies and bullying victimization varied according to the sex and the grades the students were in. The results highlight the unique and differentiated relationships between the four essential socio-emotional learning competencies and the students' experiences of bullying victimization. The study emphasized the importance of including the assessment of the school climate and specific actions organized by gender and school year for the development of bullying prevention programs, with a focus on essential socio-emotional learning competencies.

A study carried out by Cornejo and Redondo (2001) sought to verify the perception of young people regarding the school climate they experienced in their school and its relationship with other aspects of their experience in high school education. Participants were 770 students of both sexes of four high schools in the province of Santiago. Significant correlations were verified between the perception of the school climate and the establishment where the young people studied, except for the "disciplinary" climate, in which no significant differences were observed in the High School Education. The young people from the technical and professional high school in the district of San Joaquin presented a better perception of the school climate and of the "interpersonal/imaginative" and "instructional" contexts in relation to the other high schools.

Considering the results presented, it can be said that, for an individual to learn, it is necessary to interact with others, as the learning process needs to be planned with shared responsibility, taking into account the motivational factors and the interpersonal relationships that affect them (Osti & Matinelli, 2013). Therefore, it is necessary to view Elementary Education as a relevant step for the development of basic social skills so that, in the future, the student can achieve academic success and obtain more elaborate social skills (McCabe & Altamura, 2011).

Social skills are understood as "classes of social behaviors that can only be classified as such when they contribute to social competence" (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2017, p. 21), and social competence is understood as "an evaluative construct of the performance of a subject (thoughts, feelings and actions) in an interpersonal activity that fulfills the objectives of the individual and the demands of the situation and culture, generating positive results according to instrumental criteria and ethics" (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2017, p. 37). These authors highlighted six interdependent classes of social skills as being important for a satisfactory interpersonal relationship in adolescence, these being: empathy, self-control, civility, assertiveness, affective approach and social resourcefulness. In the educational environment, Social Skills Training (SST) is considered an important strategy for the development of social competencies, assertiveness and, in particular, civility, as this is a fundamental skill for any place that has rules (Cardoso, Coelho, Coelho, & Martins, 2017).

Relating in a positive and competent manner is not a trivial behavior. In order for relationships to be preserved and developed and for students to simultaneously achieve their interactional goals it is necessary to acquire social skills. Therefore, when practices that enable the acquisition of social skills are not developed, the impact of the deficit of this repertoire on the social interactions of the subject can be perceived, affecting in some way the quality of life of the individuals involved in these relationships and, consequently, in the environment.

In this context, studies that identified the acquisition of social skills through SST presented a reduction in problematic behaviors in students (Elias & Amaral, 2016; Faijão, Carneiro, Bruni, & Montiel, 2010). SST is understood as a

[...] set of planned activities that structure learning processes, mediated and conducted by a therapist or coordinator, aiming to: 1) increase the frequency and/or improve the proficiency of the SS already learned, but deficient; 2) teach new and meaningful SS; and 3) diminish or extinguish behaviors that compete with these abilities (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2010, p. 128).

In the international context, Rodríguez and Montanero (2017) evaluated the effects of a SST program on the competence and social cohesion of a 2nd year class. The study included 22 students with special educational needs in relation to the development of social competence (10 male and 12 female), aged between 13 and 14 years old, from the lower-middle socioeconomic level in the province of Badajoz, Spain. The aim was to evaluate the three dimensions involved in the development of the program: 1. the development of assertiveness and learning specific social skills; 2. the effects on the social integration of the group; and 3. the teachers' subjective assessment of the program's development within the Tutorial Action Plan at the center. According to the teachers' reports, several conflicts occurred and these hindered integration among the students. The results of the study showed a significant increase in assertive responses only in boys. In addition, the intervention did not significantly affect the group cohesion or the integration of the students considered to be undervalued by their peers, who showed a less aggressive style of interaction than the better integrated students.

Accordingly, it can be considered that relations with schoolmates portray the main context in which social competence develops, along with most of the fundamental skills for a pertinent adaptation to social competence (Díaz-Aguado, 1996). The importance of SST for the development of social skills, assertiveness and civility was the object of investigation for Cardoso et al. (2017). The study participants were 20 adolescents between 13 and 15 years of age, of both genders, students of elementary school II, of a private school in the city of Macapá. The study evaluated assertiveness and civility, as these were the points of greatest interest. The results showed that the skills of civility are correlated with those of assertiveness, that is, assertiveness (ability to deal with interpersonal situations) develops when there is good knowledge of the basic cultural norms of social coexistence. When correlating the subscales in relation to difficulty in assertiveness and civility, it was concluded that greater difficulty in assertiveness equated to greater difficulty in civility; this way, students presented a deficit in the social ability of civility.

Souza (2018) sought to identify the effects of SST on social skills, behavior problems and academic performance with a sample of 5th year elementary education students aged from 10 to 13 years of age (M = 10.3 and SD = 0.8), who lived and studied in an area of social vulnerability. An SST program was developed with 51 students divided into two groups, the intervention group with 25 students and the control group with 26 students, from a public school in Rio de Janeiro. A total of 10 sessions were carried out to develop the skills of: civility, self-control, assertiveness and academic skills. The results showed positive gains for most students participating in the intervention and higher scores in the intervention group compared to the control group in all variables.

Another study that evaluated the effects of a social skills program was performed by Pereira-Guizzo, Del Prette, Del Prette, & Leme (2018), seeking to evaluate the effects of an intervention with adolescents from unfavorable socio-economic contexts. The aim was to overcome interpersonal difficulties in different daily situations of adolescents looking for work opportunities. The participants were low-income young people aged between 14 and 16 years of age and were divided into two groups (intervention and control). The intervention was carried out in eight sessions, lasting approximately 90 minutes, distributed twice a week. The Social Skills Inventory for Adolescents (SSIA) and fieldnotes were used. The results showed a significant effect on overcoming interpersonal difficulties related to the social skills of self-control and social-sexual approach.

The study by Faijão et al. (2010) carried out with elementary education students was developed with the aim of performing an intervention in social skills to minimize undisciplined behavior in the class and improve social interactions. The training was developed with 23 students aged between 14 and 15 years of age, of both sexes, in an elementary education school in the city of São Paulo. Pre and post-tests were applied considering the skills of effective communication, critical thinking, self-knowledge and interpersonal relationships. Particularly for the girls, the results of the post-test were favorable for the acquisition of more skillful behaviors. The school is a potentially favorable environment for the development of a socially competent behavioral repertoire, as it provides the student with experiences of social integration with the environment, with the chance to develop and improve new skills (Pasche, Vidal, Schott, Barbosa, & Vasconcellos, 2019).

The school climate is especially affected by the social competence of those that interact in this environment: students, teachers, workers and managers. From the students' point of view, the school climate can be perceived as favorable to academic performance when there are behaviors that express cordiality, empathy and assertiveness, among other social skills. However, the students have not always acquired the necessary skills to deal with others, to interact and to solve their problems in the classroom. With regards to the school climate being perceived as favorable to learning, it is possible to assume that Social Skills Training may have effects on the students' behavior and, consequently, on the environment, making it more conducive to the acquisition of knowledge. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of a SST program on the school climate with students in the final year of elementary education. The investigation also sought to add to the few studies at the national level on SST and school climate, considering that studies on this topic can contribute to the identification of fundamental aspects of the school context.

From the contributions of the theoretical framework, the study aimed to verify four assumptions: 1. the existence of a positive association between social skills and school climate for all students; 2. the existence of a positive association in social skills and school climate before and after the intervention; 3. the existence of a significant difference in school climate and social skills after the intervention; 4. the existence of a significant difference in school climate and social skills for the experimental group.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

The participants were 21 students, 11 in the experimental group, aged between 14 and 16 years of age (MD = 14.31; SD = 0.75), with 6 female participants (54%) and five male participants (45%). There were 10 students in the control group, aged between 13 and 16 (MD = 14.58; SD = 1.16), with 3 female participants (30%) and 7 male participants (70%). All studied at a single public school, located in Niterói, in the state of Rio de Janeiro and were in the 9th grade of the elementary education. They were selected by convenience, from a sample of 90 students (three 9th grade classes). Those that volunteered were chosen at random for both groups (experimental and control). The intervention took place in the second semester of the 2019 academic year.

2.2 Instruments

The Social Skills Inventory for Adolescents - IHSA-Del-Prette (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2009): it is an instrument for adolescents (aged 12-17), consisting of 38 items, based on self-reports about everyday life situations. The frequency indicator shows how much the adolescent behaves in a certain way in a situation. The difficulty indicator shows how difficult it is to behave in the manner described in the item, referring to the subjective cost reported by the respondent. The IHSA produces a score for the six factors and a general score. The following internal consistency indices were found for the frequency indicators: total score (α = 0.89); 1. empathy (α = 0.82); 2. self-control (α = 0.72); 3. civility (α = 0.75); 4. assertiveness (α = 0.67); 5. affective approach (α = 0.69); and 6. social resourcefulness (α = 0.61). The values obtained for the difficulty indicator were: total score (α = 0.90); 1. empathy (α = 0.86); 2. self-control (α = 0.75); 3. civility (α = 0.83); 4. assertiveness (α = 0.72); 5. affective approach (α = 0.67); and 6. social resourcefulness (α = 0.51).

The Delaware School Climate Scale-Student - DSCS-S (Bear, Gaskins, Blank, & Chen, 2011, adapted to the Brazilian reality by Bear et al., 2016): it consists of 28 items that assess the school climate from the student's perspective, organized in the dimensions of social support and structure, in six factors: 1. teacher-student relations (α = 0.80); 2. student-student relations (α = 0.77); 3. school safety (α = 0.83); 4. fairness of rules (α = 0.74); 5. student engagement (α = 0.76); and 6. bullying (α = 0.79).

2.3 Intervention procedures

The DSCS-S and IHSA were applied after the orientation procedure in the first meeting and again in the last meeting. Ten sessions were held, once a week, lasting 50 minutes each, during the school day. The methodology used was a dialogical explanation, use of audiovisual resources with the presentation of short videos followed by a discussion of group and/or individual experiences, activities to systematize knowledge at home and oral assessment of the participant in each session. The themes developed were: in the first session, social skills and self-knowledge; in the second session, social skills for asking for help from classmates and for communication; in the third session, social skills for answering questions in class and clarifying doubts; in the fourth session, social skills for apologizing, knowing how to give compliments to colleagues, thanking colleagues for their compliments and for the student-teacher relationship; in the fifth session, social skills for asking to participate in activities and for the student-teacher relationship; in the sixth session, social skills for assertiveness, standards and rules of the school and clarity of the rules; in the seventh session, standards and rules, sense of belonging and engagement; in the eighth session, social skills to identify and recognize feelings, emotions, bullying and offering help; in the ninth session, social skills for knowing how to accept jokes, refusing abusive requests from colleagues and bullying; and in the final session, we sought to identify the subjects of the intervention that the students considered significant and reapplied the study instruments.

2.4 Ethical considerations

Contact was made with schools for the application of the instruments before and after the intervention in the 9th grade classes of elementary education. All the parents signed a consent form authorizing their children to participate in the study and the students also signed a consent form, in compliance with the ethical aspects proposed by the Regulatory Guidelines and Standards for Research involving human subjects, set out in Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council. This study was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the Salgado de Oliveira University, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro and was approved under number 10064319.2.0000.5289.

2.5 Data analysis

The analyses were performed using non-parametric tests due to the sample size. Initially, the relationships between the school climate dimensions and the social skills factors before and after the intervention were investigated, using Spearman's p, in the complete database. Then, Spearman's correlation was calculated in the database of the control group and of the experimental group with the same variables. In order to test the differences between the groups, Mann-Whitney tests for independent samples were conducted between the control and experimental groups before and after the intervention (time one and time two, respectively). In order to verify whether the intervention had any effect, another test of difference of groups of repeated measures was conducted, using the Wilcoxon test, in the control (before and after) and experimental (before and after) groups. The means of the participants were compared in terms of school climate and social skills. For data analysis, a minimum significance level of p < 0.05 was considered.

3. Results

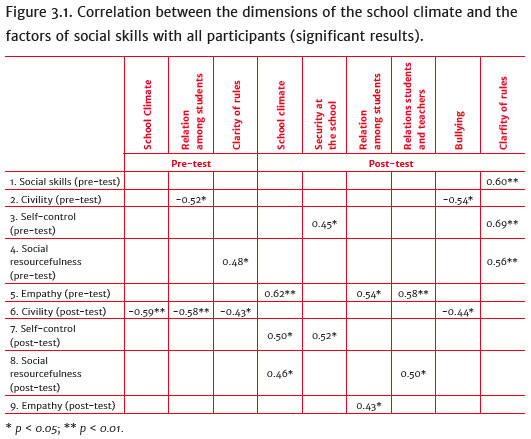

Figure 3.1 shows the significant results of Spearman's correlations between the school climate dimensions and the social skills factors with all participants, before (pre-test) and after (post-test) the intervention.

It was observed that a better general school climate in the pre-test equated to lower levels of civility in the post-test. Also, the better the school safety in the pre-test, the lower the levels of civility in the pre and post-test. Finally, higher levels of fairness of the rules in the pre-test equated to higher levels of social resourcefulness in the pre-test and lower levels of civility in the post-test. The post-test data showed that the higher the levels of school climate in the post-test, the greater the levels of empathy in the pre-test, and of self-control and social resourcefulness in the post-test. Furthermore, the greater the school safety in the post-test, the greater the self-control in the pre- and post-test. Better student-student relations in the post-test also equated to greater empathy in the pre and post-test, while better teacher-student relations in the post-test equated to better social resourcefulness in the pre and post-test. The higher the levels of bullying in the post-test, the lower the levels of civility in the pre and post-test. Finally, the higher the levels of fairness of rules in the post-test, the greater the social skills repertoire, self-control and social resourcefulness in the pre-test.

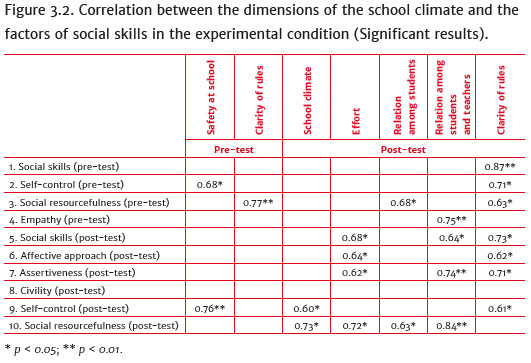

In the second analysis, Spearman's correlations with the participants of the intervention group were calculated for the social skills factors and the school climate dimensions, before and after the intervention. Figure 3.2 shows that school safety in the pre-test was positively correlated with self-control in the pre and post-test. In addition, the fairness of rules dimension in the pre-test was positively correlated with social resourcefulness in the pre-test. The school climate in the post-test presented a positive correlation with the self-control and social resourcefulness factors. Engagement in the post-test presented a positive correlation with social skills, affective approach, assertiveness and social resourcefulness in the post-test. The student-student relations in the post-test had a positive correlation with social resourcefulness in the pre and post-test. The teacher-student relations in the post-test was positively correlated with empathy in the pre-test, and social skills, assertiveness and social resourcefulness in the post-test. The fairness of rules in the post-test was positively correlated with social skills, self-control, social resourcefulness in the pre-test, and with social skills, affective approach, assertiveness and self-control in the post-test.

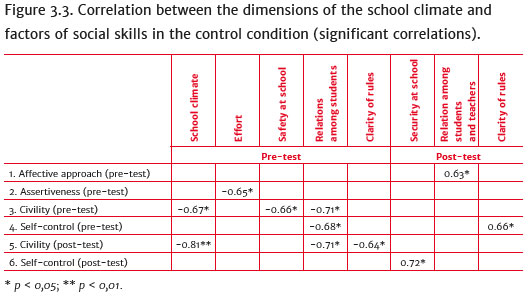

In the third analysis, the Spearman correlations of the participants of the control group were calculated for the social skills factors and school climate dimensions, before and after the intervention. The results of Spearman's correlations were different from the experimental group (Figure 3.3). There were negative correlations between school climate in the pre-test and civility in the pre and post-test. The engagement component in the pre-test was negatively correlated with assertiveness in the pre-test. School safety in the pre-test had a negative correlation with civility in the pre-test. The teacher-student relations in the pre-test was negatively correlated with civility and self-control in the pre-test, and with civility in the post-test. The fairness of rules component in the pre-test was negatively correlated with civility in the post-test. School safety in the post-test had a negative correlation with civility in the post-test. The teacher-student relations in the post-test was positively correlated with the affective approach in the pre-test. Finally, fairness of rules correlated positively with self-control in the pre-test.

In the fourth analysis, differences between the experimental and control groups were investigated. For this analysis, Mann-Whitney tests for independent samples between groups, before and after the intervention (time one and time two, respectively), were performed. Regarding the difference between the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention, the groups did not differ in any of the variables prior to the intervention. These being, before the intervention: school climate (U = 54.0; p = 0.94); engagement (U = 37.5; p = 0.21); school safety (U = 40.0; p = 0.21); student-student relations (U = 33.0; p = 0.12); teacher-student relations (U = 45.5; p = 0.50); bullying (U = 40.5; p = 0.30); fairness of rules (U = 40.0; p = 0.28); social skills (U = 47.0; p = 0.57); affective approach (U = 50.5; p = 0.75); assertiveness (U = 37.0; p = 0.20); civility (U = 53.0; p = 0.89); self-control (U = 46; p = 0.52); social resourcefulness (U = 54.5; p = 0.97); and empathy (U = 32.5; p = 0.11). The same pattern was found after the intervention. With the exception of the empathy factor (U = 26.5; p = 0.04), the other variables did not differ: school climate (U = 42.0; p = 0.36); engagement (U = 52.5; p = 0.86); school safety (U = 42.0; p = 0.34); student-student relations (U = 49.0; p = 0.22); teacher-student relations (U = 47.0; p = 0.57); bullying (U = 48.0; p = 0.62); fairness of rules (U = 49.0; p = 0.67); social skills (U = 40.0; p = 0.29); affective approach (U = 51.5; p = 0.80); assertiveness (U = 39.0; p = 0.26); civility (U = 47.0; p = 0.57); self-control (U = 35; p = 0.16); and social resourcefulness (U = 42.5; p = 0.38).

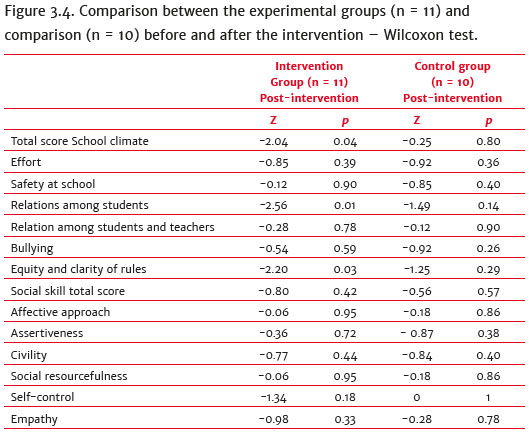

The last analysis sought to verify whether the intervention had any effect, using the Wilcoxon test, comparing the moments before and after the intervention. As shown in Figure 3.4, the result indicated that after the intervention the participants had different levels of: school climate (Z = -2.04; p = 0.04), student-student relations (Z = -2.56; p = -0.01) and fairness of rules (Z = -2.20; p = 0.03), with no significant differences in the intervention group in the social skills variable. The control group presented no significant differences in any of the variables.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the study showed positive associations between the social skills factors and the school climate dimensions for all participants. In the intervention group, positive correlations were found indicating that the safer the students felt at school, the better the level of self-control in the pre and post-test. The more they recognized the rules as fair, clear and equal in the pre-test, the better their social resourcefulness. Cornejo and Redondo (2001) identified from the correlations studied that students that were able to better understand the school climate were those who had better conditions for participation in school, in the context of the classroom and student representation; in addition, they emphasized the importance of the voice of young people, with them needing to be heard as much as those responsible for them.

In relation to the post-test, when the perception of the school climate improved, higher self-control and social resourcefulness scores were found. The more engaged students were at school, the more elaborate the repertoire of social skills in relation to the affective approach, assertiveness and social resourcefulness. Some studies, as well as the results found, associated students' perceptions of a positive school climate with school engagement, in the sense of greater academic achievement (Bear et al., 2011; Brand, Felner, Seitsinger, Burns, & Bolton, 2008). The better the student-student relations in the post-test, the better their social resourcefulness in the pre and post-test. The better the student-teacher relations (pre and post-test), the greater the levels of empathy in the pre-test, and the greater the repertoire of social skills, assertiveness and social resourcefulness in the post-test. In relation to this aspect, Cornejo and Redondo (2001) suggested that teachers that value their students' performance and learning abilities possibly demonstrate better interpersonal and instructional relationships with the students that have better school performance. Finally, in the post-test, the better the perception of the school climate, the higher the levels of self-control and social resourcefulness (post-test). Souza (2018) found positive gains for the majority of participants in an intervention with students of the 5th year of Elementary Education and higher scores in the intervention group in relation to the control group in the social skills, behavior problems and academic performance variables. These findings reveal the importance of SST as a fundamental tool for the socio-emotional development of students and for improving the school climate, since, by investing in the improvement of social skills, we are improving the perception of the school climate.

In relation to the associations made with the control group, negative correlations were identified indicating that the lower the perception of school climate in the pre-test, the lower the level of civility in the pre and post-test; and the lower the engagement in the pre-test, the lower the level of assertiveness in the pre-test. It was also found that a lower perception of school safety equated to lower levels of civility in the pre-test; and worse teacher-student relations in the pre-test was associated with lower levels of civility (pre and post-test) and self-control in the pre-test. Furthermore, the lower the comprehension of the fairness of rules in the pre-test, the lower the level of civility in the post-test. Positive correlations were found, indicating that higher school safety in the post-test resulted in higher levels of civility in the post-test; and better teacher-student relations in the post-test equated to a better level of affective approach in the pre-test. Finally, the greater the fairness of rules, the greater the self-control in the pre-test. The data reveal a significant improvement in the dimensions of the school climate, with these results being similar to the findings obtained by Vinha et al. (2016), who highlighted gains acquired through a structured project with conflict prevention actions, with the development of more respectful relationships, an increase in the feeling of general well-being and an improvement in the school climate.

In the comparison between the experimental and control groups in the pre and post-tests, there is no significant difference between the groups prior to the intervention; while in the post-test there was a significant difference only in the Empathy factor. Faijão et al. (2010), in a training program with Elementary Education students, evaluated the skills of effective communication, critical thinking, self-knowledge and interpersonal relationships (pre and post-test) and identified that the results of the post-test were positive for the acquisition of more skillful behavior, especially in girls. Other similar results were observed by Pereira-Guizzo et al. (2018) in the post-intervention. The study revealed that, with the intervention, the experimental group obtained a significant decrease in the scale of difficulties in the self-control factor. In the study by Elias and Amaral (2016), students that underwent a social skills intervention showed better resourcefulness in relation to behavioral problems and school performance, allowing to infer that the social skills interventions could constitute a concrete option for performing preventive work on social skills.

Regarding the difference between the experimental and control groups, it was observed that, for the participants in the experimental and control groups, there was no difference between the variables at the moment prior to the intervention. However, at the moment after the intervention, a difference was observed in the school climate, with a decrease in the perception of school climate in the student-student relations and in the fairness of rules in the post-test for the experimental group. It can be inferred that after the intervention, the participants became more critical when they learnt about aspects of the school climate, assessing the perception of the climate in a more negative way, as well as the relationships with their peers and the fairness of rules. Similar to this finding, Ttofi and Farrington (2011) found that preventive interventions focused on reducing bullying and aimed at changing the school climate showed a tendency to increase intolerance to the bullying phenomenon. In the study developed by Rodríguez and Montanero (2017) with students with special educational needs in terms of developing their social competence, no significant changes were observed after the intervention. Some improvements were identified in the specific social skills of "asking favors-thanking people" and in "talking" and a reduction in the ability to "anticipate and resolve problems", as well as "putting oneself in the place of others".

In general, it was observed that the proposed intervention satisfactorily contemplated the objective of identifying the effects of SST on the school climate of students in the 9th grade of Elementary Education in a public school. In general, the associations between some social skills factors and the school climate dimensions were confirmed. There was a development of social skills that were sometimes lacking or deficient in the elementary education students, as well as the strengthening of emotional bonds and the improvement of social competencies, considering the aim of the SST in the healthy development of students to foster autonomy in dealing with new challenges and problems in the future.

One of the weaknesses of this study is the application of the intervention with the students only, since the literature reveals that, for a school climate intervention proposal to be effective, it must include the participation of the different actors involved in the school environment (managers, teachers and workers). Future school climate intervention programs should be extended to the entire school team, including academic performance and sociodemographic aspects as variables to be investigated. It is suggested that empirical studies in the Brazilian context regarding the effects of SST on the school climate should be carried out, aiming to provide robust results. Another suggestion would be to carry out a follow-up at three and six months after the training, in order to identify whether the changes that occurred in the experimental group remain over time.

References

Bear, G. G., Gaskins, C., Blank, J., & Chen, F. F. (2011). Delaware School Climate Survey-Student: Its factor structure, concurrent validity, and reliability. Journal of School Psychology, 49,157-174. [ Links ]

Bear, G. G., Holst, B., Lisboa, C., Chen, D., Yang, C., & Chen, F. F. (2016). A Brazilian Portuguese survey of school climate: Evidence of validity and reliability. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 4(3),165-178. [ Links ]

Brand, S., Felner, R. D., Seitsinger, A., Burns, A., & Bolton, N. (2008). A large scale study of the assessment of the social environment of middle and secondary schools: The validity and utility of teachers' ratings of school climate, cultural pluralism, and safety problems for understanding school effects and school improvement. Journal of School Psychology, 46,507-535. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.12.001 [ Links ]

Cardoso, J. K. S., Coelho, L. B. Coelho, & Martins, M. G. T. (2017). Crescer para saber: O treinamento de habilidades sociais e assertividade com adolescentes em âmbito escolar. Revista Eletrônica Estácio Papirus, 4(2),215-231. [ Links ]

Colombo, T. F. S. (2018). A convivência na escola a partir da perspectiva de alunos e professores: Investigando o clima e a sua relação com o desempenho escolar em uma instituição de ensino fundamental II e médio (Tese de doutorado, Universidade Estadual Paulista "Júlio de Mesquita Filho", Marília, SP, Brasil). [ Links ]

Cornejo, R., & Redondo, J. M. (2001). El clima escolar percibido por los alumnos de enseñanza media: Una investigación en algunos liceos de la región metropolitana. Ultima Década, 9(15),11-52. doi: 10.4067/S0718-22362001000200002 [ Links ]

Del Prette, A., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2010). Programa vivencial de habilidades sociais: Características sob a perspectiva da análise do comportamento. In M. R. Garcia, P. Abreu, E. N. P., Cillo, P. B., Faleiros, & P. P. Queiroz (Orgs.), Comportamento e cognição: Terapia comportamental e cognitiva (pp. 127-139). Santo André: ESETec. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A., & Del Prette, A. (2017). Competência social e habilidades sociais: Manual teórico-prático. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2009). Avaliação de habilidades sociais: Bases conceituais, instrumentos e procedimentos. In A. Del Prette & Z. A. P. Del Prette (Orgs.), Psicologia das habilidades sociais: Diversidade teórica e suas implicações (pp. 187-229). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Díaz-Aguado, M. J. (1996). Escuela y tolerancia. Madrid: Pirámide. [ Links ]

Elias, L. C. S., & Amaral, V. M. (2016). Habilidades sociais, comportamentos e desempenho acadêmico em escolares antes e após a intervenção. Psico USF, 21(1),49-61. [ Links ]

Faijão, W., Carneiro, G. R. S., Bruni, A. R., & Montiel, J. M. (2010). Aplicação de um treinamento de habilidades sociais em crianças do ensino fundamental. Encontro: Revista de Psicologia, 13(19),69-89. [ Links ]

Haynes, N., Emmons, C., & Ben-Avie, M. (1997). School climate as a factor in student adjustment and achievement. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 83,321-329. [ Links ]

McCabe, P. C., & Altamura, M. (2011). Empirically valid strategies to improve social and emotional competence of preschool children. Psychology in the Schools, 48(5),513-540. [ Links ]

Osti, A., & Matinelli, S. C. (2013). Desempenho escolar: Análise comparativa em função do sexo e percepção dos estudantes. Educação e Pesquisa, ahead of print, 1-11. [ Links ]

Pasche, A. D, Vidal, J. L., Schott, F., Barbosa, T. P., & Vasconcellos, S. J. L. (2019). Treinamento de habilidades sociais no contexto escolar: Um relato de experiência. Revista de Psicologia da Imed, 11(2),166-179 [ Links ]

Pereira-Guizzo, C. S., Del Prette, A., Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Leme, V. B. R. (2018). Programa de habilidades sociais para adolescentes em preparação para o trabalho. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 22(3),573-581. doi: 10.1590/2175-35392018035449 [ Links ]

Rodríguez, S., & Montanero, M. (2017). Estudio del entrenamiento en habilidades sociales de un grupo de 2º de la E.S.O. Tarbiya, Revista de Investigación e Innovación Educativa, (33). Retrieved from https://revistas.uam.es/tarbiya/article/view/7256 [ Links ]

Souza, M. S. (2018). Treinamento de habilidades sociais para alunos do ensino fundamental I em situação de vulnerabilidade social (Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Salgado de Oliveira, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil). [ Links ]

Treviño, E. (2010). Factores asociados al logro cognitivo de los estudiantes de América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago: Llece, Unesco. [ Links ]

Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and metal-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7,27-56. [ Links ]

Vinha, T. P., Morais, A., Tognetta, L. R. P., Azzi, R. G., Aragão, A. M. F., Marques, C. A. E., Silva, L. M. F., Moro, A., Aragão, A. M. F., & Morais, A. (2018). O clima escolar na perspectiva dos alunos de escolas públicas. Educação e Cultura Contemporânea, 15(40),163-186. doi: 10.5935/2238-1279.20180052 [ Links ]

Vinha, T. P., Morais, A., Tognetta, L. R. P., Azzi, R. G., Aragão, A. M. F., Marques, C. A. E., Silva, L. M. F., Moro, A., Vivaldi, F. M. D C., Ramos, A. M., Oliveira, M. T. A., & Bozza, T. C. L. (2016). O clima escolar e a convivência respeitosa nas instituições educativas. Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, 27(4),96-127. doi: 10.18222/eae.v27i64.3747 [ Links ]

Yang, C., Chan, M., & Ma, T. (2020). School-wide social emotional learning (SEL) and bullying victimization: Moderating role of school climate in elementary, middle, and high schools. Journal of School Psychology, 82,49-69. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Giselle Glória B. dos Santos

Universidade Niterói, Rua Marechal Deodoro, 263, Centro

Niterói, RJ, Brazil. CEP 24030-060

E-mail: gbsantos25@gmail.com

Submission: 30/06/2020

Acceptance: 16/04/2021

Authors' notes: Giselle Glória B. Dos Santos, Departament of Psychology, Salgado de Oliveira University (Universo); Adriana B. Soares, Departament of Psychology, Salgado de Oliveira University (Universo); Rafael V. S. Bastos, Departament of Psychology, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio).