Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.23 no.2 São Paulo maio/ago. 2021

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPCP12606

ARTICLES

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

Social skills and social anxiety in childhood and adolescence: a literature review

Habilidades sociales y ansiedad social en la infancia y la adolescencia: revisión de la literatura

Mirella R. NobreI ; Lucas C. FreitasII

; Lucas C. FreitasII

IFederal University of Alagoas (UFAL), Maceió, AL, Brazil

IIFederal University of São João del-Rei, São João del-Rei, MG, Brazil

ABSTRACT

This study aimed to conduct a literature review of 20 years of empirical research (1997 to 2017) that studied the relationship between social skills and social anxiety in childhood and adolescence. Searches were carried out in the BVS, Scielo, Eric, PsycINFO, PsycNet, PubMed and Science Direct databases, using the keywords: social skills, social competence, social anxiety, social phobia, children and adolescents. A previous selection, based on titles and abstracts, recovered 40 potentially eligible articles. After the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two judges, 16 articles were selected to be fully read and analyzed based on general categories. In addition, studies were grouped into three sets based on the results presented. Overall, the results pointed to a negative correlation between some specific classes of social skills and social anxiety. The results of this review have implications for conducting future studies, as well as for planning interventions focused on social skills deficits in children and adolescents with social anxiety.

Keywords: social skills; social competence; social anxiety; childhood; adolescence.

RESUMEN

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo realizar una revisión de la literatura de 20 años de investigación empírica (1997 a 2017) que estudió la relación entre las habilidades sociales y la ansiedad social en la infancia y la adolescencia. Las búsquedas se realizaron en las bases de datos BVS, SciELO, Eric, PsycInfo, PsycNet, PubMed y ScienceDirect, utilizando las palabras clave: habilidades sociales, competencia social, ansiedad social, fobia social, niños y adolescentes. Una selección previa, basada en títulos y resúmenes, recuperó 40 artículos potencialmente elegibles. Tras la aplicación de los criterios de inclusión y exclusión por parte de dos jueces, se seleccionaron 16 artículos para ser leídos en su totalidad y analizados en base a categorías generales. Además, los estudios se agruparon en tres conjuntos según los resultados presentados. En general, los resultados apuntaron a una correlación negativa entre algunas clases específicas de habilidades sociales y la ansiedad social. Los resultados de esta revisión tienen implicaciones para la realización de estudios futuros, así como para la planificación de intervenciones centradas en los déficits de habilidades sociales en niños y adolescentes con ansiedad social.

Palabras clave: habilidades sociales; competencia social; ansiedad social; infancia; adolescencia.

1. Introduction

Social skills are understood by Del Prette and Del Prette (2017) as different classes of social behaviors in an individual's repertoire that contribute to social competence, favoring a healthy and productive relationship with other interlocutors. These skills can generate high expectations that will maximize reinforcers and minimize aversive stimulation for the individual (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2009, 2017).

Expressing attitudes, feelings, desires, opinions, or rights in an adaptive and assertive manner are behaviors related to the concept of social skills, which may reduce the probability of a problem occurring in social situations. Social skills are considered as a factor favoring child development, as they play an important role in children's performance in school, in learning, and in socio-cognitive development (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2005; Del Prette, Del Prette, Oliveira, Gresham, & Vance, 2012).

Social skills are learned during childhood through formal or informal processes of social interaction. However, in an environment that does not favor learning, deficits in the acquisition and development of these skills may occur (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2017). Such deficits are considered risk factors for psychosocial functioning, since they are associated with behavioral problems and psychological disorders, such as anxiety disorders (Caballo, 2003; Del Prette & Del Prette, 2011).

Among anxiety disorders, Angélico, Crippa, and Loureiro (2006) highlighted the involvement of the repertoire of social skills in the diagnosis of social anxiety disorder. The authors emphasize that the difficulties related to the repertoire of social skills impair an individual's social functioning and adaptability.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2014), states that anxiety disorders are characterized by excessive fear and anxiety, as well as behavior problems that are related to the diagnosis. These disorders differ in the types of objects or situations that generate fear, anxiety, or avoidance behavior. Although these can be comorbidities, they are characterized according to the types of situations that are feared or avoided and by the content of the cognitions related to each situation.

Among the anxiety disorders, there is the Social Anxiety Disorder, or Social Phobia, presented in the DSM-5 as excessive fear and anxiety that persist in the face of social situations, in which the individual is exposed to strangers and may be observed or assessed, or even go through performance situations (American Psychiatric Association, 2014). Social anxiety disorder is usually associated with social skills because it is directly related to the difficulties of social interaction. It is common to find deficits in the repertoire of these skills together with symptoms or correlates of psychological disorders commonly constituted by interpersonal difficulties experienced in childhood (Souza, 2017).

In childhood, social anxiety can be expected in the face of certain experiences. However, the presentation of intense levels of social anxiety can cause negative impacts on social functioning in some children and adolescents, which can result in emotional well-being issues, difficulties in dealing with fears, academic difficulties, and a greater degree of subjective discomfort (Albano & Detweiler, 2001).

Two Brazilian literature review studies associated social skills and social anxiety in adults (Angélico et al., 2006; Levitan, Rangé, & Nardi, 2008), but no reviews were found regarding the population of children and adolescents. In the first review, the authors sought to identify in the literature, between 2000 and 2005, empirical research on the topic in order to carry out a critical analysis of the methodologies used in the studies (Angélico et al., 2006). This review presented 16 articles divided into two categories: therapeutic modalities - application and comparison of clinical interventions (N = 6), and characterization of the social skills repertoire (N = 10). Based on the results, the authors suggest the realization of new studies with more precise methodologies to support the generalization found in the literature regarding the association between social skills and social anxiety.

In the literature review carried out by Levitan et al. (2008), the association of social skills with agoraphobia and social anxiety was investigated. In this study, social skills deficits were found in surveys that assessed the performance of individuals with social anxiety in unstructured tasks. The authors indicated that longitudinal studies may assist in the possible identification of factors that precede social anxiety, in addition to pointing out that more conclusive results on the relationships between the studied variables may be important for the elaboration of treatment protocols.

According to Isolan, Pheula, & Manfro (2007), the onset of social anxiety disorder was between eight and 15 years of age in 75% of the individuals who present this issue. This disorder usually starts in the children's history of difficulties in social interactions with peers and/or adults, manifesting itself as social inhibition and shyness (Souza, 2017). In this context, the importance of conducting literature review studies that link social skills and social anxiety in childhood and adolescence is emphasized.

Considering the existing correlation between social skills and social anxiety and the possible negative consequences of this relationship throughout human development, this article aimed to perform a literature review of 20 years of empirical research (from 1997 to 2017) that studied these two variables in populations of children and adolescents. It was sought to identify and describe the research characteristics in terms of the following categories of analysis: year of publication, types and size of sample, assessment procedures, instruments used, and results found. Specifically regarding the results of the studies, the objective was to identify and describe the main components and classes of social skills assessed as deficient in children and adolescents with social anxiety, grouped into three sets of results: 1. skills deficits; 2. negative cognitions; and 3. social skills deficits and negative cognition.

2. Methods

A survey of empirical studies published between 1997 and June 2017 on social skills and social anxiety in childhood and adolescence was carried out in virtual databases. The descriptors used in the research were: social skills, social competence, social anxiety, social phobia, children, and adolescents, in the Portuguese language in the VHL, and SciELO databases, and their English-language equivalents (social skills, social competence, social anxiety, social phobia, children, and adolescents) in the Eric, PsycINFO, PsycNet, PubMed, and Science Direct platforms. Initially, a total of 5,048 articles were found, using the Boolean operator AND between keywords. From the initial reading of only the titles and abstracts, studies that were potentially relevant to the research were identified, with 40 articles previously selected in that first moment. The inclusion criterion in this pre-selection of articles was based on whether these studies mentioned social skills, social competence, social anxiety, and/or social phobia variables in their titles or abstracts.

After this stage, a new selection was made from reading the abstracts of the 40 previously selected articles, applying the following inclusion criteria: 1. studies published in article format; 2. studies with children and adolescents; 3. studies published in the last 20 years (1997 to June 2017); 4. empirical research reporting studies; 5. studies published in the English, Portuguese, and/or Spanish languages. The exclusion criteria were: 1. studies with identification of another psychological disorder or medical condition; 2. studies on the effectiveness or efficacy of interventions; 3. psychometric studies for instrument validation; 4. drug studies; 5. studies that involved social skills training (SST). After applying these criteria to the 40 articles surveyed in the previous selection, the 16 articles were definitively selected for full reading and consideration in this study. At the time of final selection of the articles, two independent assessors agreed that the studies met the adopted criteria. The following categories were created from the information found in the studies: Authors (year), sample, assessment procedures, instruments, and results.

After reading the selected articles, three sets of results were created, based on the analysis of the results presented in these studies. These three sets of results were identified and organized in consensus by the two authors. The first set presents the studies in which social skills deficits were found in the participating children. The second set consisted of studies that concluded in their analyzes that the participating children had negative cognitions. Finally, in the third set, there were the studies that presented social skills deficits as well as negative cognitions in their participants.

3. Results

The results are described according to the information contained in the studies that comprised this research. The year of publication, the sample of each study, the assessment procedures, the instruments used, and the results presented in the articles were taken into account.

Figure 3.1 shows the flowchart of the article selection process, considering all the databases used. A total of 5,048 articles were initially found and, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 16 studies were analyzed.

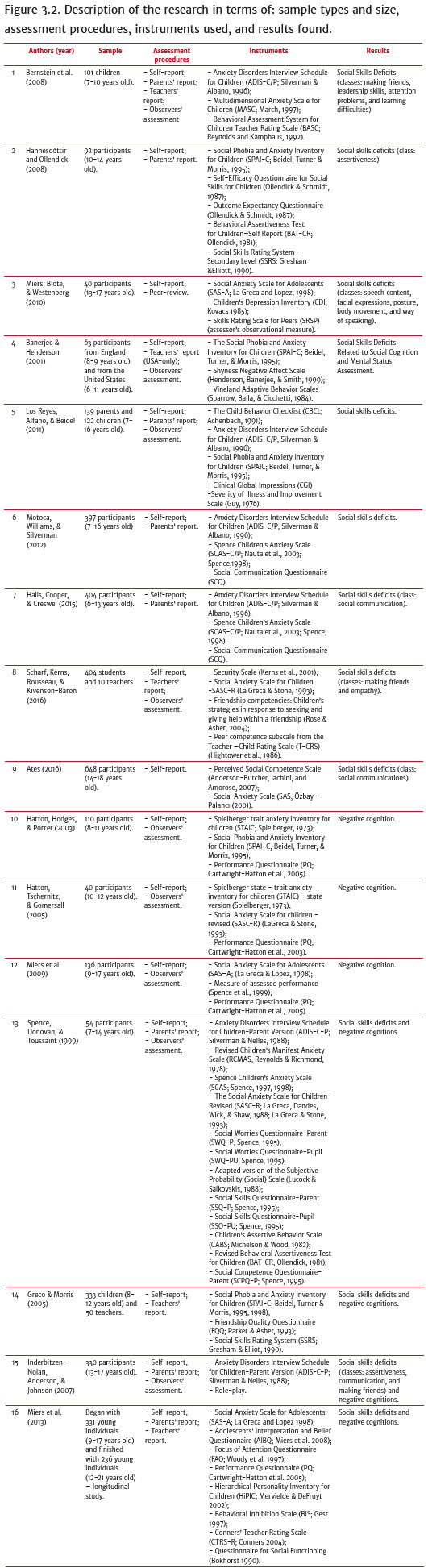

Figure 3.2 describes the articles that make up the corpus of this research in relation to the types and size of the samples, the assessment procedures, the instruments used, and the results presented.

All studies described in Figure 3.2 were carried out with children and adolescents and the minimum age of the participants was six and the maximum age was 21 years old. The oldest study found in this research was the one performed by Spence, Donovan, and Toussaint (1999) and the most recent ones were those by Scharf, Kerns, Rousseau, & Kivenson-Baron (2016) and Ates (2016). Regarding the design of the studies, only the study by Miers, Blöte, Rooij, Bokhorst, & Westenberg (2013) can be characterized as longitudinal, while the other 15 studies presented cross-sectional designs. The study that used the largest number of participants was the one by Ates (2016) with a sample of 648 adolescents and the smallest sample, of 40 participants, was found in two studies: the one by Hatton, Tschernitz, & Gomersall (2005) and the one by Miers, Blöte, & Westenberg (2010).

Regarding the assessment procedures, all 16 studies were self-reported, in the assessment process of the participating children and adolescents. In addition to the self-report, nine articles also made use of observer assessment, eight articles assessed the parents' reports, and only five used the teachers' report concurrently. Only in the study by Miers et al. (2010) peer observation was used, in which young people of the same age group as the participants were the assessors.

Thirty-eight different instruments were used to carry out the assessments of different variables of the participants. Among the instruments used to assess anxiety, the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule (ADIS-C-P) stands out, which was used in six studies to aid in the diagnosis of Social Anxiety Disorder - developed by Silverman and Albano (1996), it consists of a structured diagnostic interview, based on the DSM-IV.

Another instrument used to assess anxiety, found in five articles, was the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children (SPAI-C), developed by Beidel, Turner, & Morris (1998). It is a self-report measure containing 26 items developed to assess the frequency and extent of social anxiety experienced by children and adolescents. It is also worth mentioning the recurrent use of the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A; La Greca & Lopez, 1998), used in four studies and the Social Anxiety Scale for Children, (SASC-R; La Greca & Stone, 1993), used in three studies.

To assess the repertoire of social skills in research, the use of the Performance Questionnaire (PQ; Cartwright-Hatton et al., 2003; Cartwright-Hatton, Tschernitz, & Gomersall, 2005) was used in four studies (Hatton et al., 2003; Hatton et al., 2005; Miers, et al., 2009; Miers, Blöte, Bokhorst, & Westenberg, 2013). The original PQ is a rating scale of nine items, three items refer to the micro-behaviors displayed during the speech task (for example, how loud and clear the speaker's voice was), three items refer to the overall impression made by the child (for example, how friendly did you look?) and three items are related to how nervous the child looked during the task (for example, how did you look?) (Hatton et al., 2005).

It is also highlighted the use of the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS), an inventory developed by Gresham and Elliot (1990) and validated in Brazil by Freitas and Del Prette (2015), in three studies: the ones by Greco and Morris (2005), Hannesdóttir and Ollendick (2008), and Motoca, Williams, & Silverman (2012). It is an instrument that assesses the social skills of children and adolescents and can be applied to the students themselves, as well as their teachers and parents.

With regard to the results obtained by the studies, these were grouped according to three different sets of results, namely:

1) Social skills deficits (nine articles): studies that addressed in their results the classes of social skills that were considered as deficits in children with social anxiety;

2) Negative cognitions (three articles): studies that demonstrated that the participants had negative cognitions in the situations assessed and, in these studies, there was a differentiation between cognition and behavior; and

3) Social skills deficits and negative cognition (four articles): studies that presented both behavioral difficulties in social skills and negative cognitions related to the performance of activities in their results.

In this last set of studies, behaviors and cognitions were understood as distinct processes, preserving the authors' definitions for each component (social skills and cognition).

About the first set of studies, it was noted that eight studies specified the social skills classes assessed as deficient in the participating individuals: communication, assertiveness, empathy, making friends, speaking in public, leadership skills, social skills related to social cognition, and assessment of mental status. This last class is considered by Caballo (2003) as a cognitive assessment carried out by an individual in the face of situations or stimuli, being determined by the conceptions that he or she has about the world and about him or herself. This author also considers that cognition is a component of social skills.

It is noteworthy that the most presented classes were: communication - three studies (Ates, 2016; Halls, Cooper, & Creswell, 2015; Inderbitzen-Nolan, Anderson, & Johnson, 2007); Making friends - three studies (Bernstein, Bernat, Davis, & Layne, 2008; Inderbitzen-Nolan et al., 2007; Scharf et al., 2016); and Assertiveness - two studies (Hannesdóttir & Ollendick, 2008; Inderbitzen-Nolan et al., 2007).

In the second set generated from the results, three studies (Hatton et al., 2003; Hatton et al., 2005; Miers, et al., 2009) presenting negative cognition as a factor associated with social anxiety were found. In the study by Hatton et al. (2003), social skills were indistinguishable between groups of children with and without social anxiety. The authors concluded that socially anxious children do not necessarily have social skills deficits, but that their own assessment would be influenced by their degree of nervousness (negative cognition). Hatton et al. (2005) suggested that the nervousness of socially anxious children significantly influenced their self-assessment and that they may not necessarily have social skills deficits, but only believe that they have this deficit due to the nervousness in which they find themselves in social situations. In the third study of this set Miers et al. (2009) concluded that the participants with social anxiety rated their performance more negatively than young people with lower levels of social anxiety, with the first group having negative cognitions arising from their perceptions of nervousness.

Given this second set of studies, it is valid to conceptualize what the authors define as negative cognition. The cognitive model for anxiety disorders proposes that the content of thoughts has an important role in the development and maintenance of anxiety. However, the model points out that individuals may present flaws in information processing, with a tendency to distort reality by assessing their interpersonal experiences in a dysfunctional way and interpreting situations of social interactions as more threatening than they really are (Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 1985; D'El Rey & Pacini, 2006; Knapp & Beck, 2008).

According to this model, individuals with social phobia experience anxiety in advance or during social situations, since they have excessive expectations regarding negative results in social contexts, assessing their own performance in a very critical way, with negative cognitions, thus, increasing their anxiety experience (Spence et al., 1999).

The third set of studies refers to studies that reported social skills deficits and negative cognition in their results, comprising four studies: the one by Spence et al. (1999); the study by Greco and Morris (2005); by Inderbitzen-Nolan et al., (2007); and by Miers et al. (2013). The results of the study by Spence et al. (1999) showed that children diagnosed with social phobia had a lower performance during social tasks and also rated themselves more negatively. The study by Greco and Morris (2005) examined the mediating and moderating role of social skills and close friendships in the relationship between peer acceptance and social anxiety. Among the several results obtained, it was highlighted that social anxiety was associated with low levels of peer acceptance, and that this relationship was mediated, in part, by general social skills deficits. In addition, girls who rated their best friendships with negative attributes (e.g., conflicts and betrayals) had lower social preference ratings by their peers and high levels of social anxiety.

Among the studies of the third set, only the one by Inderbitzen-Nolan et al. (2007) specified the classes of social skills assessed as deficient, namely: assertiveness, communication, and making friends. In the longitudinal survey by Miers et al. (2013), it was found that the trajectory of social anxiety during adolescence was influenced by variables related to both cognition (self-reported negative interpretations and self-centered attention) and social competence (worse social skills assessed by observers during a speech task and greater social problems) at school, assessed by the teacher. Still with regard to this set of studies, it is worth noting that not all studies specified the types of negative cognition homogeneously.

4. Discussion

This study carried out a literature review of 20 years of empirical research (from 1997 to 2017) that studied social skills and social anxiety in populations of children and adolescents. Most of the studies found pointed to the negative correlation between social skills and social anxiety for clinical groups and for the population in general. However, the literature still has gaps regarding the causal relationship between these two factors, that is, are social skills deficits the cause of social anxiety or is the presence of symptoms of social anxiety that impairs the development of social skills? (Stravynski, Kyparissis, & Amado, 2010). The results of the literature review by Levitan et al. (2008), carried out based on studies published in electronic databases and on the references of the selected papers, corroborate the data found in this review, and it is possible to state that there is still no consensus as to the aspects and conditions that are involved in the development of social anxiety. However, it should be noted that, in the study by Levitan et al. (2008), there was no restriction in relation to the age range of the participants and that the reviewed research included patients with social phobia or agoraphobia.

As reported in the results, of the thirteen studies that pointed to social skills deficits in participants with social anxiety - Set 1, eight studies addressed the specific classes that can trigger symptoms of social anxiety, namely: communication, assertiveness, empathy, making friends, public speaking, leadership skills and social skills related to social cognition and mental status assessment. However, no research has shown the degree of prediction of these specific classes, that is, how much each class of skills contributes to the development of social anxiety symptoms. The three deficit classes most frequently found in the studies were: communication, making friends, and assertiveness.

Communication is a class of social skills that is related to initiating and maintaining a conversation, asking, and answering questions, asking and giving feedback, praising and thanking, and giving an opinion. The behavior of communicating can occur directly (face to face) or indirectly (using electronic means of communication). In the former, verbal communication is always associated with non-verbal communication, which can complement, illustrate, replace, and sometimes contradict verbal messages (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2017).

The making and keeping friendships class is geared towards starting conversations, hearing/making confidences, showing kindness, keeping in touch, asking personal questions without being invasive, offering free information (self-disclosure), expressing feelings, praising, suggesting activities, and expressing solidarity in the face of problems (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2017). The assertiveness class, in turn, focuses on defending their own rights and the rights of others, expressing negative feelings and asking for behavior changes, talking about their own qualities and defects, refusing requests, apologizing and admitting failures, negotiating conflicting interests and handling criticism (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2017). Deficits in these three classes of social skills can impair the individual's behavioral performance, increasing their level of anxiety in situations of exposure, assessment, judgment, or momentary events that require social interaction.

In view of this panorama, it is suggested that further studies be carried out in order to present the prediction levels of specific social skills classes in social anxiety, considering that the identification of these classes may help in the assessment of this anxiety in childhood and adolescence and contribute to the literature. In addition, based on studies of this nature, it would be possible to offer empirical data and important information for the social skills training used in the treatment of social anxiety disorder, which can be directed with greater emphasis to the most deficient social skills classes.

Some studies presented social skills deficits that influenced the performance of groups with social anxiety in the 2008 review (Levitan et al., 2008). However, there are studies highlighted in the review that did not indicate the relationship between social skills and social anxiety, identifying cognition as the only factor that influences the development of anxiety in the face of social situations. This same finding can be observed in the present review. Three studies included in Set 2 - Negative cognitions - (Hatton et al., 2003; Hatton et al., 2005; Miers et al., 2009) presented negative cognition as the main factor related to the development of social anxiety symptoms. In addition to these, in the four studies that composed Set 3 - Social skills deficits and negative cognition - (Greco & Morris, 2005; Inderbitzen-Nolan et al., 2007; Miers et al., 2013; Spence et al., 1999), negative cognition appeared concurrently with social skills deficits.

Vianna, Campos, & Fernandez (2009) and Levitan et al. (2008) reinforced the information raised by studies that found negative cognitions in their results. These authors state that children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder are more likely to have the following difficulties: negative interpretations in the face of everyday social situations; thoughts focused on the possibility of rejection or humiliation, based on their performance; and the environment is interpreted as threatening and their own beliefs and abilities are perceived as negative (Levitan et al., 2008; Vianna et al., 2009).

In addition, self-demandingness can be generated as a result of the dysfunctional belief that it is necessary to have a quality performance to be valued in social situations. However, the high level of demands increases the degree of anxiety when developing an interaction, leading to frustration when the individual loses control and something does not happen as expected (D'El Rey & Pacini, 2006).

Starting from a cognitive view, considering the population in general, the distortion that is most present in the cognitive model of Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is catastrophizing. This is a classic information processing error that occurs when a neutral stimulus is distorted and interpreted as negative, while a positive and safe stimulus is not considered by the individual (Souza, 2017). These distorted and negative cognitions can trigger physical symptoms of anxiety, as well as behaviors that generate discomfort and reinforce the idea of inadequacy, rejection, and humiliation, contributing to the individual's withdrawal and avoidance of interpersonal relationships (Ito, Roso, Tiwari, Kendall, & Asbahr, 2008; Souza, 2017).

For Caballo (2003), social skills have behavioral components (eye contact, speech latency, gestures, posture, voice tone, among others) and cognitive components (perceptions about communication environments), making it possible to observe that, according to some theoretical models, cognition can also be considered as a component of social skills. However, the studies that comprised Sets 2 and 3, whose results presented the negative cognition of young participants, did not consider cognition as a component of social skills in their research. This aspect possibly reflects the divergence of theoretical perspectives adopted in the different studies. It is also noteworthy that, even among researchers who work primarily in the field of Social Skills, there is no consensus on the specific cognitive components that can be considered classes of social skills, such as the portfolio of Del Prette and Del Prette (2017).

In view of the studies found, one can question the fact that there is no consensus in the research found in the literature on the main triggering factor of social anxiety disorder, namely, social skills deficits or negative cognition. Therefore, further studies must be carried out to answer this question more appropriately.

Considering the instruments used to assess social skills in the studies found, it is possible to verify that there was not a standardized instrument for the data collection stage in the studies. This inconsistency was also highlighted by Angélico et al. (2006) in a literature review on the same theme in adulthood, stating that the use of a standardized instrument could generate more validity and reliability to the research results.

No Brazilian empirical research conducted with children and adolescents was included in the present review, considering the search period, the descriptors and the databases used. However, two other recent studies, carried out with Brazilian children and adolescents, were recovered through other search sources, but which did not enter the corpus of this review due to their date of publication (2018) and/or the format of the document (book chapter) (Freitas, Porfírio, & Buarque, 2018; Magalhães, Angélico, & Oliveira, 2018). Even so, it is emphasized that the lack of studies in the country can imply difficulties in the identification and treatment of social anxiety disorder in the Brazilian context.

Generally speaking, regarding the social skills classes, there is no consensus regarding which of the studies found in this review can be better or worse predictors of social anxiety. Regarding negative cognitions, the types of distortions found in children and adolescents were not specified. These gaps suggest questions that can be answered by empirical studies using, for example, longitudinal designs. In addition, it is understood that new studies on the nature of the relationship between these variables can bring improvements in issues related to the prevention and treatment of social anxiety in childhood and adolescence.

As possible implications of the results obtained in the present review, Miers et al. (2013) highlight the importance of developing and improving social skills in the treatment of social anxiety in childhood, in order to increase the chances of a child seeking access to their peer groups and, later, receiving positive responses from their social interactions. One way to improve and develop such skills is the SST which is characterized as a set of activities planned and structured based on learning processes, which must be mediated and conducted by a facilitating therapist (Caballo, 2003). In addition to having the objective of acquiring, learning, and improving social skills, the SST also aims to acquire the other requirements for social competences, gradually providing social interaction practices (Del Prette & Del Prette, 2017). Individuals with social anxiety can benefit from the SST in the treatment of these symptoms (Caballo, 2003), especially regarding the classes of social skills found to be deficient in this literature review.

It is highlighted that only empirical studies published in journals were included in this study, which could be understood as a limitation. It is suggested, therefore, that further literature review studies on the same topic should be carried out with the inclusion of other types of publications, such as dissertations, theses, or books. Thus, the search may be broader and contribute to the explanation of gaps not yet satisfactorily answered by the articles in this study.

References

Albano, A. M., & Detweiler, M. F. (2001). The developmental and clinical impact of social anxiety and social phobia in children and adolescents. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. Dibartolo, From social anxiety to social phobia: Multiple perspectives (pp. 162-178). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association (2014). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington: APA. [ Links ]

Angélico, A. P., Crippa, J. A. S., & Loureiro, S. R. (2006). Fobia social e habilidades sociais: Uma revisão da literatura. Interação em Psicologia, 10(1),113-125. Retrieved from https://revistas.ufpr.br/psicologia/article/viewFile/5738/4175 [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., & Morris, T. L. (1998). Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [ Links ]

Caballo, V. E. (2003). Manual de avaliação e treinamento das habilidades sociais. São Paulo: Santos. [ Links ]

Cartwright-Hatton, S., Tschernitz, N., & Gomersall, H. (2005). Social anxiety in children: Social skills deficit, or cognitive distortion? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43,131-141. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.003 [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2005). Psicologia das habilidades sociais na infância: Teoria e prática. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2009). Avaliação de habilidades sociais: Bases conceituais, instrumentos e procedimentos. In Z. A. P. Del Prette & A. Del Prette (Eds.), Psicologia das habilidades sociais: Diversidade teórica e suas implicações (pp. 189-231). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2011). Habilidades sociais: Intervenções em grupo. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2017). Competência social e habilidades sociais: Manual teórico prático. Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Del Prette, Z. A. P., Del Prette, A., Oliveira, L. A., Gresham, F. M., & Vance, M. J. (2012). Role of social performance in predicting learning problems: Prediction of risk using logistic regression analysis. School Psychology International Journal, 2,1-16. doi: 10.1177/0020715211430373 [ Links ]

D'El Rey, G. J. F., & Pacini, C. A. (2006). Terapia cognitive-comportamental da fobia social: Modelos e técnicas. Psicologia em estudo, 11(2),269-275. [ Links ]

Freitas, L. C., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2015). Social Skills Rating System - Brazilian version: New exploratory and confirmatory factorial analyse. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 33(1),135-156. doi: 10.12804/apl33.01.2015.10 [ Links ]

Freitas, L. C.; Porfírio, J. C. C., & Buarque, C. N. L. (2018). Indicadores de ansiedade social infantil e suas relações com habilidades sociais e problemas de comportamento. Psicologia e Pesquisa, 12(2),1-10. doi: 10.24879/2018001200200207 [ Links ]

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services. [ Links ]

Isolan, L., Pheula, G., & Manfro, G.G. (2007). Tratamento do transtorno de ansiedade social em crianças e adolescentes. Revista de Psiquiatra Clínica, 34(3),32-125. doi: 10.1590/S0101-60832007000300004 [ Links ]

Ito, L. M., Roso, M. C., Tiwari, S., Kendall, P. C., & Asbahr, F. R. (2008). Terapia cognitivo-comportamental da fobia social. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 30(supl. II),96-101. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462008000600007 [ Links ]

Knapp, P., & Beck, A. T. (2008). Fundamentos, modelos conceituais, aplicações e pesquisa da terapia cognitiva. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 30(supl II),54-64. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462008000600002 [ Links ]

La Greca, A. M., & Lopez, N. (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26,83-94. doi: 10.1023/A:1022684520514 [ Links ]

La Greca, A. M., & Stone, W. L. (1993). Social Anxiety Scale for Children - Revised: Factor structure and concurrent validity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 22,17-27. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_2 [ Links ]

Levitan, M., Rangé, B., & Nardi, A. E. (2008). Habilidades sociais na agorafobia e fobia social. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 24(1),95-100. doi: 10.1590/S0102-37722008000100011 [ Links ]

Magalhães, L. A., Angélico, A. P., & Oliveira, M. S. (2018). Social skills and self-esteem in adolescents with social anxiety disorder. In F. L. Osório & M. F. Donadon (Orgs.), Social anxiety disorder: Recognition, diagnosis and management (pp. 65-94). New York: Nova Science Publishers. [ Links ]

Silverman, W. K., & Albano, A. M. (1996). Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child Version. Clinician manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation. [ Links ]

Souza, M. A. M. de (2017). Transtorno de ansiedade social e mutismo seletivo na infância. In R. M. Caminha, M. G. Caminha, & C. A. Dutra (Orgs.), A prática cognitiva na infância e adolescência (Vol. 1, pp. 329-365). Novo Haburgo: Sinopsys. [ Links ]

Stravynski, A., Kyparissis, A., & Amado, D. (2010). Social phobia as a deficit in social skills. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. Dibartolo (Orgs.), Social anxiety: Clinical, developmental, and social perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 147-176). London: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Vianna, R. R. A. B., Campos, A. A., & Fernandez, J. L. (2009). Transtorno de ansiedade na infância e adolescência: Uma revisão. Revista Brasileira de Terapias Cognitivas, 5(1),46-61. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext& pid=S1808-56872009000100005&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Apendix -References of the articles that made up the corpus of this research

Ates, B. (2016). Social phobia as a predictor of social competence perceived by teenagers. International Education Studies, 9(4),77-86. doi: 10.5539/ies.v9n4p77 [ Links ]

Banerjee, R., & Henderson, L. (2001). Social-cognitive factors in childhood social anxiety: A preliminary investigation. Social Development, 10(4),558-572. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00180 [ Links ]

Bernstein G. A., Bernat, D., Davis, A. A., & Layne, A. E. (2008). Symptom presentation and classroom functioning in a nonclinical sample of children with social phobia. Depression and Anxiety, 25,752-760. doi: 10.1002/da.20315 [ Links ]

Cartwright-Hatton, S., Hodges, L., & Porter, J. (2003). Social anxiety in childhood: The relationship with self and observer rated social skills. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 44(5),737-742. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00159 [ Links ]

Greco, L. A., & Morris, T. L. (2005). Factors influencing the link between social anxiety and peer acceptance: Contributions of social skills and close friendships during middle childhood. Behavior Therapy, 36,197-205. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80068-1 [ Links ]

Halls, G., Cooper, P. J., & Creswell, C. (2015). Social communication deficits: Specific associations with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172,38-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.040 [ Links ]

Hannesdóttir, D. K., & Ollendick, T. H. (2008). Social cognition and social anxiety among Icelandic schoolchildren. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 29(4),43-58. doi: 10.1300/J019v29n04_03 [ Links ]

Hatton, S. C., Hodges, L., & Porter, J. (2003). Social anxiety in childhood: The relationship with self and observer rated social skills. The Journal of Child Psychology Psychiatry, 44(5),737-742. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00159 [ Links ]

Hatton, S. C., Tschernitz, N., & Gomersall, H. (2005). Social anxiety in children: Social skills deficit, or cognitive distortion? Behavior Research and Therapy, 43(1),131-141. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.003 [ Links ]

Inderbitzen-Nolan, H. M, Anderson, E. R., & Johnson, H. S. (2007). Subjective versus objective behavioral ratings following two analogue tasks: A comparison of socially phobic and non-anxious adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21,76-90. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.013 [ Links ]

Los Reys, A. D., Alfano, C. A., & Beidel, D. C. (2011). Are clinicians' assessments of improvements in children's functioning ''global''? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(2),281-294. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546043 [ Links ]

Miers, A. C., Blöte, A. W., Bokhorst, C. L., & Westenberg, P. M. (2009). Negative self-evaluations and the relation to performance level in socially anxious children and adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47,1043-1049. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.017 [ Links ]

Miers, A. C., Blöte, A. W., Rooij, M., Bokhorst, C. L., & Westenberg, P. M. (2013). Trajectories of social anxiety during adolescence and relations with cognition, social competence and temperament. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41,97-110. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9651-6 [ Links ]

Miers, A. C., Blöte, A. W., & Westenberg, P. M. (2010). Peer perceptions of social skills in socially anxious and nonanxious adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38,33-41. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9345-x [ Links ]

Motoca, L. M., Williams, S., & Silverman, W. K. (2012). Social skills as a mediator between anxiety symptoms and peer interactions among children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(3),329-336. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.668843 [ Links ]

Scharf, M., Kerns, K. A., Rousseau, S., & Kivenson-Baron, I. (2016). Mother-child attachment and social anxiety: Associations with friendship skills and peer competence of Arab children. School Psychology International, 37(3),271-288. doi: 10.1177/0143034316631179 [ Links ]

Spence, S. H., Donovan, C., & Toussaint, M. B. (1999). Social skills, social outcomes, and cognitive features of childhood social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(2),211-221. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.2.211 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mirella Rodrigues Nobre

Rua José Soares Sobrinho, 119, Le Monde Empresarial, sala 207, Jatiúca

Maceió, AL, Brazil. CEP 57036-640

E-mail: mirellarodriguesnobre@hotmail.com

Submission: 25/06/2019

Acceptance: 24/02/2021

Author notes: Mirella Rodrigues Nobre, Institute of Psychology (IP), Federal University of Alagoas (Ufal); Lucas Cordeiro Freitas, Departament of Psychology (DPSIC), Federal University of de São João del-Rei (UFSJ).

During her master's degree, Mirella R. Nobre held academic mobility at the Federal University of São João del-Rei (UFSJ), São João del Rei, MG, Brazil.