Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.22 no.2 São Paulo maio/ago. 2020

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/psicologia.v22n2p39-59

ARTICLES

PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

Translation, adaptation, and evidence of content validity of the Schema Mode Inventory

Traducción, adaptación y evidencia de validez de contenido del inventario de modo de esquema

Fabíola R. MatosI ; Joaquim Carlos RossiniII

; Joaquim Carlos RossiniII ; Renata F. F. LopesII

; Renata F. F. LopesII ; Jodi Dee H. F. do AmaralII

; Jodi Dee H. F. do AmaralII

IFederal University of Espírito Santo (UFES), Vitória, ES, Brazil

IIFederal University of Uberlândia (UFU), Uberlândia, MG, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Content validity indicates the extent to which each item of an instrument measures the phenomenon of interest and its dimension within what it proposes to investigate. This research aimed to perform the translation and to raise the validity evidence of the Schema Mode Inventory instrument, thus initiating its cultural adaptation. Eight specialists from the Schema Therapy area participated as evaluators, who answered two instruments: one investigating the Content Validity Coefficient (CVC) and another one the Kappa Concordance Analysis. From the semantic bias, results show that a large part of the instrument measures what it proposes to measure, demonstrating content validity evidence for the Brazilian context (CVC: 0.56 to 0.99; Mean Kappa overall: 0.74).

Keywords: measures; psychometry; Cognitive Therapy; Schema Therapy; Schema Mode Inventory.

RESUMEN

La validez de contenido representa la extensión con que cada elemento de un instrumento comprueba el fenómeno de interés y su dimensión dentro de lo que se propone investigar. El objetivo de esta investigación fue realizar la traducción y levantar las evidencias de validez de contenido del instrumento Schema Mode Inventory - versión reducida, iniciando así su adaptación cultural. Ocho especialistas del área de Terapia de esquema participaron como evaluadores, quienes respondieron dos instrumentos: uno investigando el Coeficiente de Validez del Contenido (CVC) y otro el Análisis de Concordancia Kappa. Los resultados indicaron que, por el sesgo semántico, gran parte del instrumento mide lo que sugiere medir, poseyendo entonces evidencias de validez de contenido para el contexto brasileño (CVC: 0,56 a 0,99; Kappa promedio general: 0,74).

Palabras clave: medidas; psicometría; Terapia Cognitiva; Terapia del Esquema; Schema Mode Inventory.

1. Introduction

Instruments that are theoretically subsidized and supported by empirical evidence are indispensable in the psychological evaluation process when it involves tests, scales, inventories, or questionnaires (Gonçalves, Oliveira, & Silva, 2018). Creating measuring instruments helps in the provision and operationalization of psychological domains and, consequently, in the testing of hypotheses and theories (Freires, Silva, Monteiro, Loureto, & Gouveia, 2017; Primi, 2010). In this same context, focusing on the psychometric parameters of psychological measures is hugely relevant, as these data make the instrument reliable, revealing its evidence of validity and accuracy (Hutz, Bandeira, & Trentini, 2015; Lerman & Haythornthwaite, 2018).

Scales and tests that come from other cultures are often based on concepts, standards, expectations, and formats present in the countries of origin (Cassepp-Borges, Balbinotti, & Teodoro, 2010; Coster & Mancini, 2015). Adapting psychological instruments from one culture to another requires specific translation procedure techniques and evidence of content validity (Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010).

Content validity indicates the extent to which each item of an instrument measures the phenomenon of interest and its dimension within what it proposes to investigate (Medeiros et al., 2015). This validation occurs in the adaptation of an instrument from another linguistic and cultural origin, and is composed of the steps of translation, back-translation, expert analysis (judges) and subsequent agreement analyses (Borsa, Damásio & Bandeira, 2012; Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010; Pernambuco, Espelt, Magalhães Junior, & Lima, 2017).

The translation should be performed by bilingual translators and the back-translation by native translators of the source language, with both versions needing to be synthesized and revised (Pernambuco et al., 2017). The analysis of judges aims to investigate the clarity, representativeness, and relevance of the items, and it is based on the judgment made by a group of experts experienced in the area, who will analyze whether the content is correct and appropriate to what is proposed (Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010; Medeiros et al., 2015).

One way to analyze the experts' agreement is through the Content Validity Coefficient (CVC) proposed by Hernández-Nieto (2002). This coefficient is calculated based on the evaluation of the judges regarding the categories: language clarity, which consists of the analysis of the language used in the items, considering the characteristics of the respondent population; practical relevance, which refers to the analysis of whether the item is essential for the instrument; and theoretical relevance, which is the analysis of the association between the item and the theory (Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010).

Regarding the evaluation of the theoretical dimension, which consists of the study of the adequacy of each item regarding the corresponding theory, and also to confirm whether the construct characterization is reliable or not, the Kappa Agreement Analysis is used (Siegel & Castellan, 1988). The objective in this step is to describe the intensity of interobserver agreement (between two or more judges) and measure the degree of agreement, beyond what would be expected merely by chance (Siegel & Castellan, 1988).

In general, obtaining evidence of content validity tends to significantly refine the instrument under analysis, as it allows for greater understanding, clarity of the terms used in the instrument, and identification of the strengths and weaknesses of a questionnaire (Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010). The present study aimed to perform the translation and to investigate the content validity evidence of the Schema Mode Inventory (SMI) instrument proposed by Lobbestael, Van Vreeswijk, Spinhoven, Schouten, and Arntz (2010). The SMI evaluates Schema Modes, which are characterized as states of self that the individual presents moment by moment, which reflect Adaptive or Maladaptive Initial Schema operations (Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2008).

Schema modes refer to the individual's overall style of functioning in specific emotional activation situations, including healthy or unhealthy feelings, thoughts, and forms of coping, which are experienced in a particular life situation (Wainer & Wainer, 2016). Often, these modes are activated by the environment in everyday situations and influence a person's way of thinking, feeling, and acting (Young et al., 2008).

Young et al. (2008) indicated the existence of ten Schema Modes: four child modes (happy, angry, impulsive, and vulnerable); three dysfunctional coping modes (detached protector, self-aggrandizer, and compliant surrenderer); two dysfunctional parent modes (demanding, punitive), and the healthy adult mode. In turn, to compose the SMI, Lobbestael et al. (2010) added to this list the Modes: undisciplined child; enraged child; detached self-soother; and bully and attack. In the clinical practice, the psychologist identifies and names the modes, explores the origins, relates them to the current problems, and demonstrates the advantages of modifying some Modes (Wainer & Wainer, 2016). The practitioner observes the dynamics of the schema modes specific to each patient. These modes need to be evaluated, and the patient needs to be psychoeducated regarding these dynamics, which emphasizes the importance of using an instrument to support this identification (Lopes, 2015; Wainer & Wainer, 2016). Therefore, this study aimed to perform the translation and investigate the evidence of content validity of the SMI in order to contribute to the adaptation of the instrument that will favor the clinical practice of the Schema Therapist.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

According to Borsa and Seize (2017), to indicate content validity evidence, experts must review the items of the instrument of interest. Accordingly, an invitation to participate in the study was sent to a non-probabilistic sample of 20 psychologists specializing in Schema Therapy. All worked in the clinical area using this theoretical approach and had Master's degrees. Participants were chosen according to the evaluation of the Lattes Curriculum and the snowball technique (experts indicating other experts).

According to Cassepp-Borges et al. (2010), for the analysis of judges, ideally, a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 5 experts would participate. The invitation was sent to 20 participants (half of them for each of the instruments) to favor the achievement of the suggested number. Regarding the first instrument, for the CVC verification, five participants responded to the form. Regarding the Kappa Concordance Analysis, three submitted their responses. Accordingly, a total of eight experts participated in this study.

2.2 Instrument

The SMI (Lobbestael et al., 2010) has 118 items that are judged on a Likert-type scale from 1 (never or almost never) to 6 (always), representing 14 schema modes (factors). It is considered as a valid measure for the evaluation of schema modes, presenting adequate internal consistency in all factors (a = from 0.79 to 0.96) (Lobbestael et al., 2010). Therefore, based on the items of the instrument, as mentioned earlier, two instruments were elaborated for the analysis of the judges: one for the CVC verification, and another one to evaluate the dimensionality according to the Kappa Agreement Analysis calculation. In the first instrument, the items were grouped according to the Schema Mode they represent in the original instrument, aiming for better organization and visualization for the analysis. There was a description of the Schema Mode and all the items related to it. The categories of language clarity, practical relevance, and theoretical relevance were evaluated on a Likert-type scale from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high), also having a space for observations and suggestions about each item of the questionnaire. Items are considered adequate when they present values above 0.8 in the CVC index (Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010). The second instrument, which aimed to calculate the Kappa coefficient, was composed of the presentation of the items as they appear in the original instrument, and the expert's task was to choose which mode each item represented. For the Kappa Agreement Analysis, only items that have scores above 0.40 present adequate agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977).

2.3 Procedures

Following approval from the Ethics Committee for Research with Human Subjects of the Federal University of Uberlandia, authorization number CAAE: 69612717.3.0000.5152, email contact was made with one of the authors of the version of interest of the SMI, Jill Lobbestael, obtaining the author's consent for the translation of the instrument into Portuguese.

The SMI was then translated from English to Portuguese by two bilingual translators to minimize possible linguistic, cultural, and comprehension biases (Borsa et al., 2012). At this stage of translation, only two items (28 and 92) needed to be reevaluated concerning the Portuguese version, as there was disagreement between the translators. Accordingly, a third bilingual translator joined the first two and agreed on specific items, the final version being: 28 - I can resolve problems in a rational way, without letting my emotions overwhelm me; 92 - I feel that I am heard, understood and valued. Finally, a synthesis of the versions was performed, and later a back-translation was performed by an English translator proficient in Portuguese.

After corrections, we obtained a single version that the judges reviewed and conducted through the Google Docs forms platform.

The following order of presentation was used for both instruments: 1) Description of the study, objectives, and instructions; 2) consent form (C.F.); 3) description of each schema mode and its respective items to be judged or the presentation of the item with the Schema Mode options to be chosen by the judge.

Experts were invited to participate in the study and, upon acceptance, the review form was made available. This could only be accessed after the participant agreed to participate in the consent form. All fields belonging to the instrument were mandatory, and the confidentiality of the participants was maintained.

3. Results

After collecting the judges' answers, the data were organized in spreadsheets, and the analysis was started by performing the CVC calculations. The CVC calculation is performed following five steps; the calculation of the means of the judges' grades; the division by the maximum value that the question could receive; the calculation of the error; dividing the value one (1) by the number of evaluating judges, increased by the same number of evaluators; and subtraction of the calculation mean obtained by the error mean (Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010). After the calculation is applied, items with a general CVC above 0.80 are considered acceptable (Cassepp-Borges et al., 2010).

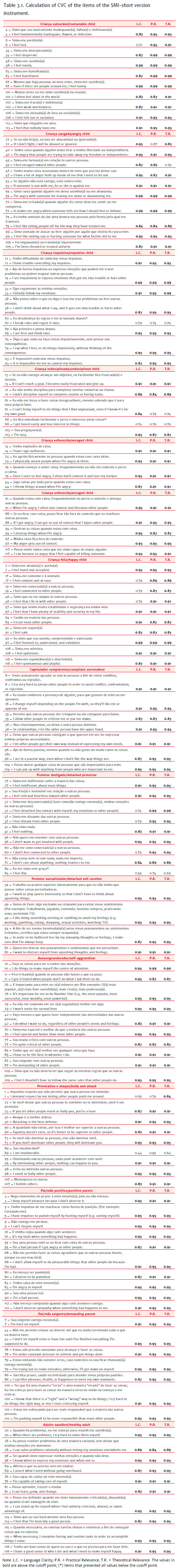

Table 3.1 presents the final CVC scores for each Schema Mode. The result of Table 3.1 refers to the evaluated characteristics of language clarity, practical relevance, and theoretical relevance for the set of items of each Schema Mode.

After analyzing the 118 items in isolation, results show only 6 presented values below 0.80, with the lowest value being obtained by the item "89- I am invulnerable" (0.56), pertaining to the bully and attack mode. Another item of this same mode also presented an insufficient value: "1 - I command respect for not allowing another person to intimidate me" (0.77). The other items that presented unsatisfactory CVC value belong to the impulsive child: "62 - I disobey the rules and later regret it" (0.77); detached protector: "84- I feel embarrassed" (0.67); and undisciplined child modes: "61- I don't force myself to do unpleasant things even though I know it's for my own good" (0.79) and "66- I get bored easily and lose interest in things" (0.77).

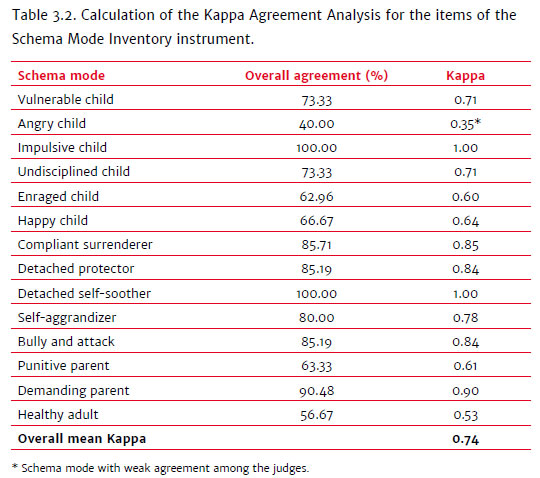

The results of the Kappa Agreement Analysis are presented in Table 3.2.

The analysis of this stage of the study was also based on the items grouped in their respective schema modes. The calculations were performed using the Online Kappa Calculator application, which checks the ratio of the number of times the experts agree about the item belonging to a construct with the maximum proportion of times they could agree, and performing the correction of the random agreement. (Siegel & Castellan, 1988). Landis and Koch (1977) present the following classification for the Kappa analysis: (<0) no agreement; (0.01-0.19) poor agreement; (0.20 to 0.39) weak agreement; (0.40 to 0.59) moderate agreement; (0.60 to 0.79) strong agreement; (0.80 to 1.00) almost perfect agreement. Scores closer to one (1) represent more satisfactory results. Therefore, only the results above 0.40 are considered (Landis & Koch, 1977).

The impulsive child and the detached self-soother modes showed full agreement among the judges, indicating that, for the experts, all the items are consistent regarding the content with each mode in question. It can also be seen that four other modes showed excellent results with a near-perfect agreement (0.80 to 1.00): Compliant Surrenderer (0.85), Detached protector (0.84), Bully and Attack (0.84) and Demanding Parent (0.90). The predominant categories were those that presented strong agreement (0.60 to 0.79), with 6 modes: vulnerable child (0.71), undisciplined child (0.71), enraged child (0.60), happy child (0.64), self-aggrandizer (0.78) and punitive parent (0.61). The healthy adult mode showed moderate agreement, as it obtained the value of 0.53 as a result of the analysis. Finally, the mode with the lowest agreement among the judges, being considered a weak agreement, was the angry child mode (0.35). Therefore, in terms of the instrument as a whole, the 0.74 Overall Mean Kappa score indicates strong agreement among the experts on the characterization of the instrument and what it aims to evaluate.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to perform the translation and investigate the content validity evidence of the SMI instrument of Lobbestael et al. (2010). We sought to evaluate the items regarding their language clarity, practical relevance, and theoretical relevance by analyzing the CVC.

The language clarity category presented the largest number of items with insufficient CVC values. Of these, three belong to the detached protector mode (32 - I feel detached (no contact with myself, my emotions or other people) 37 - I feel distant from other people; 60 - I don't feel connected to other people), two to the happy child mode (19- I feel connected to other people; 46 - I feel that I fit in with other people) and one to the vulnerable child mode (6 - I feel lost), according to the original instrument. According to the experts' evaluation and comments, the insufficient value may be associated with the lack of specificity of each item, having an expansive interpretation and generating confusion. The suggestion given by the judges was to replace the variations of the word "connection" with words such as "bond" or "contact" or to remove the items, since there are more satisfactory items for the representation of this dimension. Thus, we opted for the suppression of these items.

The practical relevance scored two items from the angry child mode as unsatisfactory (22 - If I don't fight, I will be abused or ignored; 75 - I feel like telling people off for the way they have treated me) and one from the detached protector mode (84 - I feel flat). In addition to not having satisfactory scores, these items led to questions from the experts, who indicated that their presence in the instrument was unnecessary since the angry child mode and the detached protector mode have enough items that are more relevant than these to represent them.

Also, according to the results obtained by calculating the final CVC of each item, it can be seen that three items (45, 75, and 84) obtained unsatisfactory coefficients in the category of theoretical relevance. Therefore, item 45- I feel enraged toward other people, which belongs to the angry child mode in the original instrument, did not present a relation of importance in the Brazilian version presented here, one of the reasons being, according to the experts' evaluation, the fact that it can easily be confused with the enraged child mode. Both modes are related to the irritation that the individual expresses through verbal and physical expressions of anger. However, the enraged child mode is composed of items that indicate more intense and aggressive behaviors (Wainer & Wainer, 2016). Another discrepant item was 75- I feel like telling people off for the way they have treated me, belonging to the angry child mode according to the original instrument. For the participants of this study, this item was more representative of the compliant surrenderer mode, which concerns submission to the other and obedience, passivity, and dependence (Wainer & Wainer, 2016). Finally, item 84 - I feel flat, which corresponds to the detached protector mode, according to the judges, is a short item with a wide interpretation, little specificity, and relevance.

Similarly, given the importance of verifying whether the SMI items, translated into Portuguese, are representative of schema modes according to the source study, the Kappa Agreement Analysis was performed. The results showed good overall agreement rates (Overall Mean Kappa = 0.74). The angry child mode was the only one with a poor agreement (0.35) among the judges. This may be due to the similarity this mode has to the enraged child and bully and attack modes, as they cover similar characteristics such as impatience, aggression, and feelings of anger (Wainer & Wainer, 2016).

The experts' evaluation was also in agreement with the analysis of items that differed regarding the results of the confirmatory factor analysis presented by the original instrument and the semantic analysis performed here. As in "50 - Equality doesn't exist, so it's better to be superior to other people," in which the experts identified this statement as representative of the self-aggrandizer mode, when the SMI indicates that it represents the bully and attack mode. Other examples include the items "77 - I am quite critical of other people" and "87 - I am demanding of other people", which were judged as demanding parent mode, however, according to the original results, belong to the self-aggrandizer mode. Judges might have taken the critical and demanding terms from the self-referenced form (I am), which led to the discrepancy of these items in relation to the original study. The self-aggrandizer mode implies taking others as a point of reference and understanding them as inferior, thus worthy of criticism and demands (Lobbestael et al., 2010).

It is necessary to emphasize that items 75 and 84 presented unsatisfactory scores in two categories simultaneously (practical relevance and theoretical relevance), indicating that their presence in the Brazilian instrument should be reevaluated. We emphasize the importance of exploring the need for the presence of these items in the instrument, especially those that did not achieve the minimum score in the language clarity category. In general, it was found that the SMI - reduced version presents good content validity for the Brazilian context. The results indicate that most of the instrument measures what it aims to measure, considering the content bias variable.

The use of the CVC for semantic analysis has also produced good results in other recent studies (Silveira et al., 2018), as has its use together with the Kappa Analysis (Almeida-Brasil et al., 2016). Accordingly, the results of this article provide support for the version adapted to the Brazilian context, as well as reaffirm the importance of performing content validity analyses when adapting an instrument to another country.

Despite the results cited, it is important to highlight limitations in this study that should be considered. The judges' analyses were performed through the internet. This context can provide advantages such as reaching a larger number of participants and allowing faster responses. However, it is not possible to control variables such as distraction and tiredness of the participants (considering that the instrument has many items, requiring more time for analysis). Despite this limitation, this work contributes to the cross-cultural adaptation of an instrument of great importance to the area of Schema Therapy. It is recommended that an agenda of research around the SMI continues, involving the performance of studies on exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, as well as verifying convergent and divergent evidence of the instrument. These efforts could make the SMI an instrument suitable for application in the clinical and research context, being appropriate for use in Schema Therapy, strengthening it as a theoretical and practical field.

References

Almeida-Brasil, C. C., Nascimento, E., Costa, J. O., Silveira, M. R., Bonolo, P. F., & Ceccato, M. G. B. (2016). Desenvolvimento e validação do conteúdo da escala de percepções de dificuldades com o tratamento antirretroviral. Revista Médica de Minas Gerais, 26(5),56-64. [ Links ]

Borsa, J. C., Damásio, B. F., & Bandeira, D. R. (2012). Adaptação e validação de instrumentos psicológicos entre culturas: Algumas considerações. Paidéia, 22(53),423-432. doi:10.1590/S0103-863X2012000300014 [ Links ]

Borsa, J. C., & Seize, M. M. (2017). Construção e adaptação de instrumentos psicológicos: Dois caminhos possíveis. In J. C. Borsa & B. F. Damásio, Manual de desenvolvimento de instrumentos psicológicos (pp.15-38). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Cassepp-Borges, V., Balbinotti, M. A. A., & Teodoro, M. L. M. (2010). Tradução e validação de conteúdo: Uma proposta para a adaptação de instrumentos. In L. Pasquali (Org.), Instrumentação psicológica: Fundamentos e práticas (pp. 506-520). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Coster, W. J., & Mancini, M.C. (2015). Recomendações para a tradução e adaptação. Revista de Terapia Ocupacional Universidade de São Paulo, 26(1),50-57. doi:10.11606/issn.2238-6149.v26i1p50-57 [ Links ]

Freires, L. A., Silva, J. H., Filho, Monteiro, R. P., Loureto, G. D. L., & Gouveia, V. V. (2017). Ensino da avaliação psicológica no Norte brasileiro: Analisando as ementas das disciplinas. Avaliação Psicológica, 16(2),205-214. doi:10.15689/AP.2017.1602.11 [ Links ]

Gonçalves, J., Oliveira, A., & Silva, J. (2018). Psicologia cognitivo-comportamental e experiência de estágio em psicologia clínica: Avaliação psicológica da ansiedade. Humanas Sociais & Aplicadas, 8(21). doi:10.25242/887682120181344 [ Links ]

Hernández-Nieto, R. A. (2002). Contribuciones al análisis estatístico. Mérida: Universidad de Los Andes. [ Links ]

Hutz, C. S., Bandeira, D. R., & Trentini, C. M. (2015). Psicometria. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1),159-174. [ Links ]

Lerman, S. F., & Haythornthwaite, J. (2018). Psychological evaluation and testing. In H. T. Benzon, S. N. Raja, S. M. Fishman, S.S. Liu, & S. P. Cohen (Orgs.), Essentials of pain medicine (pp. 47-52). Ontario: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Lobbestael, J., Van Vreeswijk, F. V., Spinhoven, P., Schouten, E., & Arntz, A. (2010). Reliability and Validity of the Short Schema Mode Inventory (SMI). Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 38,437-458. doi:10.1017/S1352465810000226 [ Links ]

Lopes, R. F. F. (2015). Terapia do Esquema em grupo com crianças e adolescentes. In C. B. Neufeld (Org.), Terapia cognitivo-comportamental em grupo para crianças e adolescentes (pp. 102-128). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Medeiros, R. K. S., Ferreira, M. A., Júnior, Pinto, D. P. S. R., Vitor, A. F., Santos, V. E. P., & Barichello, E. (2015). Modelo de validación de contenido de Pasquali en las investigaciones en Enfermería. Revista de Enfermagem Referência, (4),127-135. doi:10.12707/RIV14009 [ Links ]

Pernambuco, L., Espelt, A., Magalhães, H. V., Junior, & Lima, K. C. (2017). Recomendações para elaboração, tradução, adaptação transcultural e processo de validação de testes em Fonoaudiologia. CoDAS, 29(3),e20160217. doi:10.1590/2317-1782/20172016217 [ Links ]

Primi, R. (2010). Avaliação psicológica no Brasil: Fundamentos, situação atual e direções para o futuro. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 26,25-35. doi:10.1590/S0102-37722010000500003 [ Links ]

Siegel, S., & Castellan, N. (1988). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Silveira, M. B., Saldanha, R. P., Leite, J. C. C., Silva, T. O. F., Silva, T., & Filippin, L. I. (2018). Construção e validade de conteúdo de um instrumento para avaliação de quedas em idosos. Einstein, 16(2),eAO4154. doi:10.1590/s1679-45082018ao4154 [ Links ]

Wainer, R. G., & Wainer, G. (2016). O trabalho com os modos esquemáticos. In R. Wainer, K. Paim, R. Erdos, & R. Andriola (Orgs.), Terapia cognitiva focada em esquemas (pp. 145-165). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2008). Terapia do Esquema. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Fabíola Rodrigues Matos

Avenida Fernando Ferrari, 514, Bairro Goiabeiras

Vitória, ES, Brazil. CEP 29060-970

E-mail: fabiolarmatos@yahoo.com.br

Submission: 30/09/2018

Acceptance: 23/10/2019

Authors notes

Fabíola R. Matos, Postgraduate program in Psychology, Federal University of Espírito Santo (Ufes); Joaquim Carlos Rossini, Postgraduate program in Psychology, Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU); Renata F. F. Lopes, Postgraduate program in Psychology, Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU); Jodi Dee H. F. do Amaral, Multiprofessional Health Residency Program, Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU).