Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.22 no.2 São Paulo maio/ago. 2020

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/psicologia.v22n2p487-515

ARTICLES

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

Psychosomatic illness in the analytical approach: an integrative literature review

Enfermedad psicosomática en el enfoque analítico: una revisión integradora de la literatura

Iris M. Okumura ; Carlos Augusto Serbena

; Carlos Augusto Serbena ; Maribel P. Dóro

; Maribel P. Dóro

Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), RS, Brazil

ABSTRACT

It is known that studies about the dynamic mind-body aim at a better comprehension of the human being. According to the medical-scientific logic, some approaches dichotomize that interaction, relegating the term to cases of illnesses with no evident etiology. The psychosomatic approach proposes a holistic perspective on the individual, beyond the cure of physical symptoms. An integrative review on the comprehended psychosomatic was realized, in the paradigm of analytical psychology (AP). The search resulted in 44 articles that compounded theoretic-clinical discussion and/or empirical research about the object of study. Publications included philosophical and epistemological matters in psychosomatic, analysis of specific clinical cases, and possibilities of psychotherapeutic intervention. AP classic and developmental approaches are emphasized, and the main concepts found to comprehend the illness were psychic energy, teleology, synchronicity, and ego-self development. It was observed a higher concentration of articles with theoretical analysis illustrated with clinical vignettes and presentation of psychotherapeutic intervention proposals aiming to comprise the demands of the singular process in the dynamic between health and disease.

Keywords: psychosomatic; analytical psychology; individuation process; illness; mind-body.

RESUMEN

Los estudios sobre la dinámica mente-cuerpo visan mejor comprensión sobre el ser humano. Hay vertientes que dicotomizan tal interacción, relegando el término a los casos de enfermedades sin etiología evidente conforme a la lógica médico-científica. El abordaje psicosomático propone perspectiva holística, además de la cura del síntoma físico. Se realizó una revisión integrativa de la psicosomática en el paradigma de la Psicología Analítica (PA). La búsqueda resultó en 44 artículos que componían discusión teórico-clínica y/o investigación empírica. Las publicaciones abarcaban cuestiones filosóficas y epistemológicas en psicosomática, análisis sobre casos clínicos específicos y posibilidades de intervención psicoterapéutica. Se resaltan las vertientes clásica y desarrollista de la PA, y los principales conceptos encontrados para comprender la enfermedad fueron energía psíquica, teleología, sincronicidad y ego-Self desarrollo. Se observó una mayor concentración de artículos con análisis teórico ilustrados con viñetas clínicas y presentación de propuestas de intervención psicoterapéutica destinadas a comprender las demandas del proceso singular en la dinámica entre salud y enfermedad.

Palavras clave: psicosomática; Psicología Analítica; proceso de individuación; enfermedad; mente-cuerpo.

1. Introduction

The diagnosis of somatization disorders included hypochondria, pain, and other undifferentiated disorders, determined through persistent complaints of symptoms for at least six months (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). This conduct guided health professionals until 2013, proposing a new perspective of clinical practice with the publication of the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5.

The current version focuses on the persistence and severity of symptoms, as well as the framework of somatization when there is no medical-scientific evidence. Clinical practice begins to give importance to the intensity of the disturbance that symptoms exert in daily life. This is characterized by excessive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and it is the health professional's responsibility to identify these factors and refer the patient to the most appropriate specialty for the case (APA, 2013).

A somatic condition is recognized as a mental disorder. It comprises a set of signs that generates suffering and damage to personal, social, and professional activities by disturbing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes (APA, 2013).

Although the guiding conduct of the DSM-5 invites professionals to perceive the multiplicity of contexts that influence the patient, contemplative praxis about the physical symptom persists. The maintenance of reasoning to separate the physical from the emotional also occurs with the concept of psychosomatic. The term is associated with cases in which there are no defined explanations about the etiology of a disease.

From Greek etymology, psychosomatics (psyché = mind, soul; somatikós = body) is a triggering and resulting factor between emotional interactions and physical affections.

Each disease is psychosomatic since emotional factors influence all the processes of the body, through the humoral nerve pathways, and somatic and psychological phenomena occur in the same organism and are only two aspects of the same process (Alexander, 1989 as cited in Cerchiari, 2000, p. 65).

There is no precise chronological record on the debate of the mind-body relationship. The first use of the term psychosomatic is attributed to the psychiatrist Johan Cristian August Heinroth (1773-1843) in 1818 (Margets, 1950). For him, body and soul integrate a unity; mental health means the harmonic state between thought and desire; and the disease arises in the loss of this balance (Margets, 1950, p. 403). Studies were expanded and arose the psychosomatic medicine field, with the German physician Georg Walther Groddeck (1866-1934) as a pioneer in the field and a later highlight for Helen Flanders Dunbar (1902-1959), in the United States (Herrmann-Lingen, 2017b).

The theme health-disease has been present since mythology, with representatives such as Asclepius and Apollo, Greek characters who dedicated themselves to healing. It is also mythological the perception that the treatment of a disease is not limited to the physical body; subjective aspects integrate the whole person and cannot be dissociated from that context.

In Chiron's myth, the healer centaur had a wound that did not heal (Guggenbühl-Craig, 2004). The contradiction that one being half man and half god had an incurable injury shows that caring for the other implies self-care (of the soul) and that experiencing suffering can lead to transformation.

Psychosomatic analysis implies an understanding of the whole individual, applicable to the condition of health status, and also in the experience of a process of illness, including in pathologies in which the cause is well-grounded by medical science: "Health is a matter of multiple domains, and a myriad of perspectives is consistent with its complexity" (Avila, 2006, p. 164).

The physical affection with diagnostic-clinical denomination reflects emotional, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being. Also, subjective conflicts can find organic manifestations as a form of expression. The excess of specialties in the health area led to the study and focused treatment and, consequently, to distance from the perspective on the totality by professionals (Avila, 2006).

Psychological and psychosomatic sciences converge because of the unfolding of medicine since many scholars enabled the development of psychology, such as Freud and Jung. Authors of Psychology contributed to the construction of a holistic view of the individual. Psychosomatic theory becomes applicable to phenomena whose mind-body interaction act on biochemical processes (Leite, Katzer, & Ramos, 2017), in addition to hysterical, pain, allergic, and other clinical conditions frequently mentioned in the literature that dichotomize the term, given the lack of observable medical-clinical evidence (Mello, 2002). Psychosomatic diseases referred to:

[...] peptic ulcer, bronchial asthma, arterial hypertension, and ulcerative colitis, in which these psychophysical correlations were very clear and that such use still persists in certain medical media. However [...] such a conceptualization is equally valid for any disease, and the current dominant trend is unitary [...]". (Mello, 2002, p. 19-20).

Psychosomatics also aims at the holistic perspective of the human being (Herrmann-Lingen, 2017a). Thus, illness should not be diagnosed and treated exclusively in the physical sphere due to the inseparability of the psychic field. Psychic dynamics behave as an influencing factor and/or agent directly or indirectly influenced in this context.

This functioning approaches the analytical psychology (AP) by understanding the mutual influence between conscious and unconscious aspects. The data are both within the reach of ego (of consciousness) and beyond its domain possibilities (unconscious), and they are considered for the meaning (re)elaboration process from symbolic amplification. "The psyche is an equation that cannot be "solved" without the factor of the unconscious; it is a totality which includes both the empirical ego and its transconscious foundation" (Jung, 2011a, p.211, §175).

Amplification of a symbol can be contemplated through the symptom in the health-disease context. In addition to objective understanding, it can help in the (re)signification of an imbalance experienced. It is the process of "soul-making" (Clark, 1995), that is, connecting personal meaning to the event.

Some more comprehensive models compose an analysis of the patient's context, such as biopsychosocial care and holistic therapies, without refuting the importance of the cause. AP proposes a teleological perspective of illness.

Regarding psychosomatic dynamics, Jung (2011b, p. 127, §194) describes that:

Wrong functioning of the psyche can do much to injure the body, just as conversely a bodily illness can affect the psyche; for psyche and body are not separate entities but one and the same life. Thus there is seldom a bodily ailment that does not show psychic complications, even if it is not psychically caused.

Jung verified the relationship between mind and body through experiments in the Word Association Test, and the results allowed the development of the theory of complexes, initially studied for the conceptualization of affections. Life experiences generate positive and negative affects with varying levels of energy load that can constellate in the individual, manifesting itself according to the flow of the libido.

Jung's contributions to the psychological field are about the psychic structure and psychic development of the human being. More recent authors enrich the concepts based on analytical and therapeutic practice. Although there are no formally consolidated schools in AP, Samuels (1989) proposes the existence of three approaches: classical, developmental, and archetypal. They do not necessarily add new ideas to the theory but prioritize different orders. For example, classical school values the experience with Self; the developmental school values individual development; and the archetypal school focuses on working with the images. One does not cancel the other, only differ in the prioritization of clinical aspects.

Although a vast literature on psychosomatics and psychology is found, few publications are evidenced by the Jungian approach. According to Urban (2005), the idea of psychosomatic unity is not precisely found in Jung's writings. However, it is evident the understanding of mutual influence (mind-body), not being possible to discuss about the psychic without articulating it to the somatic, with the polarities (opposite and complementary pairs) as one of the key concepts of the Jungian theory. Thus, the main objective of this article was to raise the works related to Psychosomatics and AP in order to contribute to the integrative understanding of the health-disease process that encompasses the singularity of the patient, his/her disease, and the treatment itself.

2. Method

An integrative review of articles was carried out in the Capes Journal Portal for considering a vast database, as well as collecting specific journals in AP, such as the Journal of Analytical Psychology, The international journal of Jungian studies, Jung Journal, Journal of Jungian Scholarly Studies and Quaderni di Cultura Junghiana. The Biblioteca Virtual de Saúde (BVS / Virtual Health Library - VHL) was also consulted for bringing relevant articles to the area of Health Psychology. This method was chosen aiming at an overview of the object of study in question: scientific

publications with electronic access on psychosomatics from the AP's perspective.

The review in the Capes Journal Portal was carried out in two moments: the first with the fresearch resources "on the subject" and "is" (exact term), obtaining limited results; and in the second with the filters "any" and "is" (exact term) that expanded the number of related articles. The research was carried out in the languages Portuguese, English, and Spanish, with the following keywords: 1. 'Psicossomática' e 'Psicologia Analítica'; 'Psychosomatic' and 'Analytical Psychology'; 'Psicosomática' y 'Psicología Analítica'; 2. 'Psicossomática' e 'Jung'; 'Psychosomatic' and 'Jung'; 'Psicosomática' y'Jung'; 3. 'Psicossomática' e 'Representação Simbólica'; 'Psychosomatic' and 'Symbolic Representation'; 'Psicosomática' y 'Representación Simbólica.' The search in BVS database was filtered by "titles, abstract and keywords," with the same terms mentioned above.

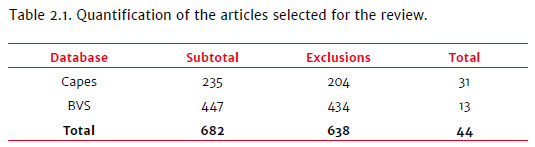

Between June and August 2018 and again in November 2019, the consultations were made after the first review of the journal's reviewers, totaling 682 papers. Table 2.1 shows the number listed in the searches, the excluded, and the selected articles.

Based on the subtotal obtained in the databases, the first author of this research read the abstracts, excluding monographs, dissertations and theses, incomplete articles, repeated and/or unavailable for online access and publications with strictly medical bias or with a different theoretical basis from the objective of this review. Those with considerations about AP were included. Finally, all selected publications (n = 44) were read to compose this article's discussion.

3. Results

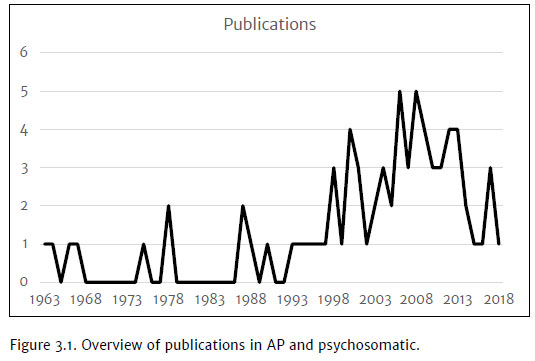

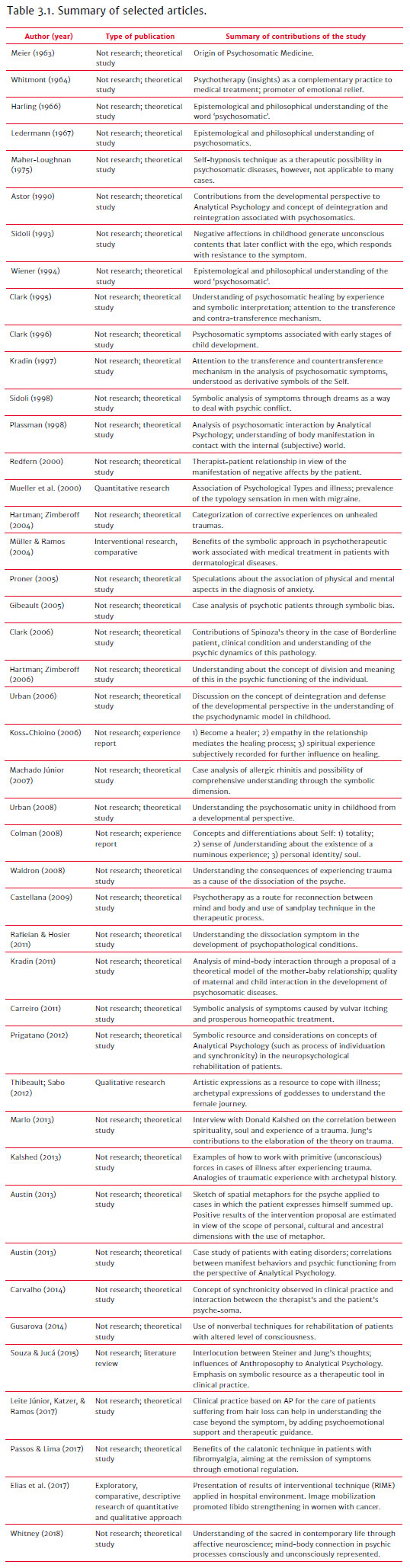

The resulting articles are predominantly in English (85%) and date from 1963 to 2018, with an increase in publications from the 1990s on. Figure 3.1 portrays the panorama of publications that relate AP and psychosomatic. A greater number of theoretical studies were observed, some elucidated with clinical vignettes (n = 25) and few researches (n = 5). Table 3.1 summarizes the selected studies.

Of the total, 50% were from journals with a theoretical framework of AP, most of which were published in the Journal of Analytical Psychology. The papers discussed the psychosomatic approach itself - philosophical and epistemological issues - and also the application of this science in the study of specific pathologies. The most published diagnostic conditions include mood, personality and eating disorders, neurological and respiratory symptoms, dermatological affections, and chronic pain. The articles were categorized according to the development of the central discussion, highlighting the items Causes of Illness and Proposals for Therapeutic Intervention, presented below.

Excluding articles that were not based on AP, the ones that were selected and contemplated Jungian theory rescued concepts and authors of psychoanalysis considering the historical background of dynamic psychiatry and Freud's direct influence on Jung's academic and personal trajectory.

The first texts that focus on the panorama of publications in AP date from the 1960s. The oldest is authored by Carl Alfred Meier (1963), a Jungian analyst, who presents an essay on Psychosomatic Medicine from the Jungian perspective. The following author, also a Jungian analyst Edward Whitmont (1964), exemplifies the adjuvant action of drug therapy with a psychological clinic in five case studies, arguing that insights from the therapeutic setting bring emotional relief from tensions that originally prevented the drug response.

This theoretical discussion model with case elucidation was found in recent studies, both with methodological support of research in academic-scientific format and in case studies presented in clinical-ensaistic language.

4. Discussion

Psychology had significant scientific impulses through empirical research supported by experimental and theoretical research (Ruckmick & Warren, 1926). Influenced by positivist science (in vogue) and aiming at the recognition of the scientific community, many authors, in an attempt to deepen the psyche-soma correlation, ended up falling on the mind-body dichotomy. Symptoms of hysterical conversion, asthma, and ulcer conditions were sometimes seen as resulting from emotional conflict or as a characteristic of the patient's personality structure (Wolff, 1971).

In its etymological sense, some articles found in this integrative review use the term psychosomatic, that is, focusing on the root of the words psyche and soma (Clark, 1996; Colman, 2008). Psychosomatic unity is understood as a totality, in view of our composition as emotional, thinking, and physical beings, that is, manifestations represented in a single substance (Clark, 2006).

The analysis of the symptom manifested by itself explains little about the etiology of the disease. This arises with the imbalance in the relationship between subject and object. Aspects such as personal life history, socio-cultural context, previous morbidity, and the psychic dynamics of the individual should be taken into account, including unconscious manifestations.

Between the conscious and the unconscious, there is a kind of "uncertainty relationship" because the observer is inseparable from the observed and always disturbs it by the act of observation. In other words, exact observation of the unconscious prejudices observation of the conscious and vice versa (Jung, 2012, p. 269, §351).

With the finding of limitations of strictly observational research, the growing interest in quantifying the subjective experience arose, being necessary to obtain the individual's narrative. "Only in this way can the observer or doctor arrive at a psychological understanding of what the patient is experiencing and what this experience means to him" (Wolff, 1971, p. 526).

While clinical practice in the Jungian approach promotes qualified listening on the patient's unique issues, it finds it difficult to contemplate the quantification of observed psychic data. Part of the Jungian field's contributions is outside the academy because they do not meet the scientific rigor. Moreover, some journals do not provide online access, publishing the material only in printed version (some with already sold out editions) and/or by paid association, which restricts the possibilities of searching the psychosomatic theme discussed in AP and support the number of works selected in this research.

Serbena (2013) published a study that reviewed academic productions between 2003 and 2008 and found that among 3722 studies, only 1% involved AP. This corroborates the perspective of contemporary authors (Tacey, 2011; Samuels, 2004 apud Tacey 2011, p. 14) that the university is not the most appropriate place to teach and discuss Jungian theory, because AP does not fit into any specific discipline due to the multiplicity that composes it - psychology, mythology, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, etc.

Samuels (1989, p. 222) reiterates the difficulty faced by deep psychologies in the scientific environment, given the impossibility of proving the phenomena observed in clinical practice.

Jung was particularly keen to assert that psychology was a natural science by arguing that its field of reference is not mental products but a natural phenomenon, the psyche. My own view is that for those who demand what they consider to be the highest scientific standards, Jungian psychology will always be wanting [...].

Among the selected articles with an analytical basis, there is a theoretical investment on the constellation of other complexes that overlap the ego. Something or an event that causes intense affective load affects the individual, who cannot resignify the experience; experience that goes beyond the possibilities of containment by the ego. It is said then, of an autonomous and personified complex that splits psychic harmony (Ramos, 2006).

The ego complex is, so to say, no longer the whole of the personality; side by side with it there exists another being, living its own life and hindering and disturbing the development of the ego-complex [...] So we can easily imagine how much the psyche is influenced when the complex gains in intensity (Jung, 2011c, p. 58, §102).

Psychosomatic is characterized by a psychoid substance in the metaphysical sense because it establishes dynamism in internal and interpersonal relations, that is, not only at the intrapsychic level but in symbolic experience with the world. The undifferentiated mind-body unity is understood within the concept of participation mystique, coined by Lévy-Bruhl and incorporated into the Jungian approach, in which subject and object remain together by a powerful unconscious identity (Clark, 1996).

The other perspective found has developmental bias with Michael Fordham [1905-1995] as the main representative. The author understands that, initially, the process of deintegration (equivalent to distancing, separation) is psychosomatic due to the child's inability to differentiate mental representations from bodily experiences (Proner, 2005 as cited in Fordham, 1985). This theoretical construction was influenced by Melanie Klein (1882-1960) and is convergent to the thought of Wilfred Bion (1897-1979).

Throughout life, some successive deintegrations and reintegrations promote the healthy development of the individual. Fordham observed that in the childhood period, the psychosomatic unit deintegrates into mind and body and reintegrates into mind-body, a process that helps to compose the sense of Self (Urban, 2005).

From the selected articles, two categories of analysis were formulated: causes of illness and intervention proposals. The Jungian approach's analysis of pathological conditions allows the symbolic perspective of the disease, that is, in addition to symptoms of the physical domain. It corroborates the decentralization of the criteria for diagnostic closure and aims at the promotion of holistic health. "The label here means less than the processes that caused the somatization [of the patient]" (Avila, 2006, p. 165).

There is an association with disorders in the psychoemotional sphere (Leite et al., 2017), either by the influence of external events or by an internal trigger that leads to and may promote the maintenance of the symptom. There is no single answer about falling ill. However, there is a consensus that this adversity may be accompanied by fragmentation in the energy flow between consciousness and unconscious or associated with a malformation of the egoic structure.

Regarding the establishment of a more balanced dynamic, Driver (2005) presents a clinical case whose analysis resulted in the difficulty in finding homeostasis between the psychological (internal) and somatic (external) environments. The author relates that this regulation depends on the development of the person and his/her egoic capacity for reflection, understanding, and nutrition of the Self. A disharmonious dynamic can lead to somatization (Driver, 2005).

Kradin (1999) comments that many etiologies of human psychopathology are derived from a super-ego rigidity. The author makes connections with Psychoanalysis and understands that as the stagnant libido is mobilized, the super-ego becomes more tolerant and reflects on a more stable personality.

In a more recent publication, Kradin (2011) raises the possibility that the Psychosomatic phenomenon is caused by a lack of maternal empathic response in the development of the child's autonomy. In line with the lack of maternal emotional connection, the etiology of Borderline Personality Disorder is inserted as an example. Clark (2006) adds the importance of mother-baby interaction since intrauterine life, as well as the role of the family (especially the father) in the relationship with the child for the ordination between psyche and soma.

This condition is characterized as a failure or lack in the development of the individual for the differentiation between fantasy and reality, subject and object; immersing him/her in a state of mind-body confusion. Clark (2006) points out that this inability to distinguish leads to the formation of a false Self or a narcissistic Self, which manifests in impulsive and (Self)destructive behaviors because they cannot endure the reality that threatens their omnipotent fantasy. The symptom is perceived as an external and strange element to the individual, and, towards the affection of a disease, the first movement is the search for answers and rational understanding of the etiology.

Kradin (2011) and Clark (2006) bring the developmental bias of AP. Initially fused, the mother-baby bond needs to be deintegrated, enabling the differentiation of the primary Self for subsequent reintegration and development of the Self as the central archetype of the individual's psychic dynamics. According to Fordham (1993, p. 9):

as the infant is brought into the relation with his environmental mother he gains experience which makes the formation of images inevitable, and it seems also inevitable that these give rise to a form of consciousness which gradually integrates to form a more and more coherent ego.

Otherwise, when this field is disturbed, the child is unable to develop psychically and does not perform the movements of deintegration and reintegration; that is, he/she has difficulty in apprehending and resignifying experiences. The mother who shelters and helps to give meaning to the emotional manifestations of the child, contributes to successful development, enabling a better-structured psyche and more fluid personality characteristics.

Still in the developmental line, Colman (2008) resumes the importance of the stage of childhood in which the notion of the individual (which characterizes the 'I' and the 'non-I') is formed. This phase is demarcated by the organization and differentiation between subject and object (Urban, 2005 as cited in Colman, 2008), leading to the construction of personal identity and, therefore, to the affirmation of having a Self. Subsequently, the division of the Self by the lack or failure in its formation can lead to the estrangement of the individual with himself/herself, that is, to face self-deprecating aspects, often unnamed (Colman, 2008), manifested in symptoms, whether diseases, behaviors, symbols in general.

Sidoli (1993) observed that many patients with somatic symptoms have a strong egoic defense. It associated the developmental theory in which Fordham postulates that the primary defense mechanism comes from the Self, activated when the mother fails to provide essential emotional care to the baby. The author attended some clinical cases in which the emergence of a primitive unconscious content was seen as something to be fought by the ego, resisting any kind of symbolic representation.

Through the classical analytical approach, there is the concept of synchronicity that converges with the psychosomatic conception. It outlines the existence of significant coincidences between internal and external events, apparently without connection or logical-causal explanation. Both happen concomitantly or temporally close to each other, being apprehended as a synchronous and significant phenomenon only if there is a personal sense linked. For Jung, synchronicity complements the factors established by traditional physics in the triad of space, time, and causality, as it includes the psychoid factor in the interaction with the world (Jung, 2018, p. 103, § 950).

Urban (2006) clarifies that synchronicity occurs in a fraction of a second in which the skills of recognition and perception connect; a meeting that results in the mapping of the subjective field. When the external event is perceived in association with the internal dynamics of the individual, a tuning occurs and, therefore, a projective identification process.

Thus, the affection of a disease can be resignified through synchronous events, when the patient notices a communication between experiences in the subject-object relationship. Concurrency implies falling on both, mind-body, internal-external; without necessarily having a cause-and-effect correlation. Events such as illness happen without the immediate control or perception of the individual. Understanding the synchronous phenomenon is beyond human rational capacity.

The Jungian paradigm understands that the confrontation between opposite pairs generates tension (therefore energy), whose resolution /attenuation occurs by the formation of a third element (Sidoli, 1993). In the health-disease context, the symptom causes a clash with the healthy condition and well-being of the individual, and the cure will happen with the attribution of meaning to the situation. Not every elaboration of meaning needs to be placed verbally, but it requires a symbol that identifies it.

Wiener (1994) points out about symptoms not manifested in diseases, those expressed by non-verbal communication, being differentiated between body language and body speech. The first is inherent to normal communication because it is integrated into the verbal expression and enables the process of symbolizing the symptom. Body speech is characterized by a primitive mode of communication present in the mother-baby relationship that, in the later development of the individual, leads to the difficulty of putting thoughts, feelings, and reflections into words.

Non-symbolization refers to alexithymia, a sign often observed in psychosomatic illness. Of Greek etymology, the term composes the absence of words for emotions; the individual cannot recognize, express, or represent what he feels or thinks, nor does he differentiate body sensations from emotional states (Cerchiari, 2000).

A more specific perspective of illness on migraine symptoms, proposed by Mueller, Gallagher, Steer, and Ciervo (2000), correlated Jungian typology with the diagnosis. The study found that there is a prevalence of migraine in men with sensing type, possibly due to high-stress reactivity. Because they perceive the world with the sense organs as a reference, sensing type people may be more susceptible to the intensity of pain or reactions that affect the physical body.

The second common category found in the articles of the integrative review was the presentation of proposals for therapeutic intervention. In addition to the theoretical discussion, the authors brought contributions from clinical practice or conducted researches.

Kradin (2011) reinforces the importance of Jung's theory of complexes as a driving force behind the change of perspective of physicians on the mind-body relationship; although most professionals maintain the conduct of prioritizing biological-scientific evidence. The author recognizes the gaps in psychosomatic science that open to challenges and, in defense of this, points out that it is necessary to explain beyond the emotional influence on the diagnosis. Only this data does not bring concrete benefits to clinical practice, nor to the patient.

Psychosomatics as an approach to patient care within the health-disease context means the application of an expanded method of perception about the interaction between biological, psychological, and social aspects (Wolff, 1971, p. 525). It is consistent with the role of the therapist guided by AP, who seeks to integrate the conscious and unconscious contents related to the patient's discourse, expanding the reported demand. If it was restricted to it, it would bring little benefit to the patient.

An analogy can be made between the components of the psychic structure and the psychotherapist's conduct. Conscious contents are considerations about the known facts, which can be approximated to the record of the patient's narrative and observable symptoms. Contents of the personal unconscious refer to the analysis of the unknown object that is directly linked to the individual's personal history, such as the clinical judgment by the affluence between demand and the context/situations that occurred outside the therapeutic setting. Finally, the collective unconscious (connection with archetypal universal issues) refers to the association of knowledge within a larger spectrum due to the common background, for example, the general behavioral characteristics of a patient with binge eating.

The first publication found that suggests a therapeutic resource as part of clinical psychological treatment brings hypnosis and self-hypnosis applied to psychosomatic disorders, aiming to enable the patient to recognize the triggers that lead to the symptoms (Maher-Loughnan, 1975). However, Maher-Loughnan (1975) does not conceive psychosomatics as a unit and recognizes some limitations of the suggestibility technique when conditioning resistant cases (greater severity by the organic classification of the disease) and by contraindicating it to patients with coexisting psychotic diseases and endogenous depression.

The symbolic interpretation by the Jungian perspective can be applied both on the data collected by the discourse and by images (mental or graphic) elaborated by the individual. The research by Elias et al. (2017) proposes a relaxation technique for 28 patients diagnosed with cancer. It was found that the exercise of guided imagination focused on the work of spirituality contributes to the increase of libido in the perception and strengthening of constructive personal resources and, therefore, to coping with the disease. Although the authors chose "psychosomatic medicin" as one of the keywords of the article, there is no exact mention of it. However, the conclusion of the study contemplates that activity in the psychic field is capable of promoting physical well-being, reinforcing the link between psyche and soma.

Gusarova (2014) presents the process-oriented approach applied to the rehabilitation of patients with neurological affection, based on the physician and Jungian analyst Arnold Mindell. The technique proposes the exit of the experience description and replaces it for the experience feeling, comprehending the teleological concept of AP, the theory of information about the human experience, and quantum physics to eliminate contradictions between experimental measure and direct experience.

According to Gusarova (2014), this technique includes the possibility of rehabilitating patients with different levels of consciousness, either in a vegetative state or with difficulties in verbal communication, unlike other methods that consider only those with verbal ability or lucidity. In addition, it comprises the observation of minimal signs of physical manifestation that serve as feedback, psychosomatic resonance, and empathy between patient and therapist. The results indicate that the relationship between psyche and body is not limited to consciousness as a field of knowledge or waking state. The interaction also occurs in unconscious flow and, therefore, treatment with unconscious patients becomes possible (unconscious in neurological terms). This approach proposes to obtain the resonance characterized by metacommunication beyond the transferential, and counter-transferential contact, usually established in traditional analytical setting (Gusarova, 2014).

Related to the importance of mobilizing the flow of energy in psychic dynamics, Kradin (1999) resumes the role played by the therapist as a psychopomp, the one that leads the soul, and considers generosity as a fundamental characteristic in the analytical process to provide greater adaptation to the egoic structure. The author points out that generosity should be understood as "an analytic position that aims at creating new psychological experiences for the patient that will mitigate the effects of harsh old introjects" (Kradin, 1999, p. 225).

It is emphasized that a healthy psychic condition is not synonymous with homeostasis, nor is it restricted to the balance of conscious and unconscious poles. Equivalent tensioning of forces tends to energy stagnation; therefore, the inertia of the individual and the possibility of manifestation of another pathological nature. The term used and goal of analytical, clinical work is fluidity, that is, it is aimed at hermeneutics. The reduction of tension serves to get out of the stiffened unilateral positioning, facilitating the transience of the dark experiences and elaboration of their meaning.

AP rescues the understanding that illness and cure make up pathways of the same process. That is, what led to the disease may be the answer to the most appropriate treatment for the individual. Therapists and patients should go in favor of the meaning of the disease because while it expresses itself, it also disguises itself in the symptom (Ávila, 2006).

Spiritual integration also permeates psychotherapy. Koss-Chioino (2006) affirms the importance of empathy, concluding that the experience of thinking and feeling as another leads to spiritual transformation and, consequently, in helping to heal the other. Investment in interpersonal relationships and empathic development raise the work of awakening the wounded healer, whether between therapist-patient or ego-Self (the healer who dwells in the patient himself).

The dichotomous mind-body perspective is outdated because every mental phenomenon implies physical processes. Psychosomatics goes from the old conception framed in disorders to the proposal of a psychosomatic approach, that is, the consideration of the biopsychosocial scope of the patient (Wolff, 1971, p. 525).

Even if the holistic conception meets the concepts of AP, articles were found in which the term psychosomatic was applied to certain types of illness without defined etiology, or in the direct association of physical symptoms with a traumatic event / psychic dysfunction. Contradictions were also observed in the understanding of psychosomatics, sometimes described as integrating parts, sometimes as an indivisible unity. However, it is noteworthy that more than 70% of the selected studies date from 1963 to 2012, prior to the publication of the DSM-5, which ends up influencing the analysis of clinical cases by health professionals, even indirectly.

This integrative review found few scientific publications on psychosomatics from the perspective of AP. The publications allowed two categories of analysis, one focusing on the causes of illness and the other with intervention proposals, valuing (psycho)therapeutic work. The results allowed the understanding of the process of illness in the classical and developmental approaches. In the first, the concepts of synchronicity and teleology were evidenced, while in the second, the process of deintegration and reintegration was highlighted.

With these findings, it is concluded that: 1) synchronicity defends the concurrency of events that culminates in the manifestation of a symptom that needs to be (re)signified; 2) the concept of teleology applies to the understanding of the purpose of illness; and 3) sense and meaning are obtained from the movement of deintegration and reintegration, necessary for the healthy psychic development of the individual.

The sickening was considered as a symbol whose origin stems from rigidity or fragmentation in the flow between conscious and unconscious contents. Towards an unstable or disturbed structure, dark elements (of negative personal experiences or archetypal motives) are taken to the field of consciousness (light); an energetic movement perceived as abrupt from the point of view of the ego. In addition to the patient's clinical condition, these elements manifest themselves outside the possibilities of control and knowledge of the individual, arising in the somatized form or overlapping the egoic complex.

The psychotherapeutic process of Jungian orientation proposes the symbolic work with the rework of the meaning of experiences and affective marks. The continence of the analytical setting promotes a sheltering environment to the patient and the possibility of propelling him/her to transformation. That is, it qualifies him/her to perceive himself/herself, his/her intrapsychic and interpersonal relationships promoting fluidity in metacommunication between conscious and unconscious elements.

The reading of psychosomatics comprises mind-body inseparability and reflects the concurrency between psychic and physical disorders. This perspective is convergent to AP, which considers the analysis of the whole human being, aiming at the interrelation of psychic dynamics to the external context of the individual.

Through the DSM-5 criteria, the APA expresses the importance of promoting comprehensive patient care, believing that the professional capable of identifying clinical demands can benefit the patient by providing a better treatment directed to demand or requesting the intervention of other expertise. This conduct with an incentive to the comprehensive evaluation and clinical judgment, that is, careful analysis of the narrative added to the patient's symptoms, will tend to eliminate the mind-body dichotomy present until the previous DSM edition (APA, 2013).

Therefore, the intervention by the symbolic approach, whether in a psychotherapeutic context or clinical research, contributes to the individual's understanding of his/her experience in relation to illness and its psychic derivations. This proposal considers the psyche-soma indissociability, therefore, the individual as a hermetic unit. Having said this, the process of (re)elaboration of meaning in the face of finding a diagnosis denotes the possibility of personal strengthening (egoic) for better management of the adverse situation, providing a more integrated experience of the patient with his new health-disease condition.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Somatic symptom disorder. Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/educational-resources/dsm-5-fact-sheets [ Links ]

Astor, J. (1990). The emergence of Fordham's model of development: a new integration in analytical psychology. The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 35(3),261-278. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1990.00261.x [ Links ]

Austin, S. (2013). Working with dissociative dynamics and the longing for excess in binge eating disorders. The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 58(3),309-326. doi:10.1111/1468-5922.12009 [ Links ]

Austin, S. (2013). Spatial metaphors and somatic communication: The embodiment of multigenerational experiences of helplessness and futility in an obese patient. The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 58(3),327-346. doi:10.1111/1468-5922.12017 [ Links ]

Avila, L. A. (2006). Somatization or psychosomatic symptoms? Psychosomatics, 47(2),163-166. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.47.2.163 [ Links ]

Carreiro, M. C. (2011). A fala do corpo: abordagem psicossomática na clínica homeopática integrada à psicologia analítica. Revista Homeopatia, 74(3),47. Retrieved from https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/hom-10612 [ Links ]

Carvalho, R. (2014). Synchronicity, the infinite unrepressed, dissociation and the interpersonal. The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 59(3),366-384. doi:10.1111/1468-5922.12085 [ Links ]

Castellana, F. (2009). Body, Matter, and Symbolic Integration: An Analysis with Sandplay in Two Parts. Jung Journal, 3(2),35-58. doi:10.1525/jung.2009.3.2.35 [ Links ]

Cerchiari, E. A. N. (2000). Psicossomática um estudo histórico e epistemológico. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 20(4),64-79. doi:10.1590/S1414-98932000000400008 [ Links ]

Clark, G. (1995). How much Jungian theory is there in my practice? Journal of Analytical Psychology, 40,343-352. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1995.00343.x [ Links ]

Clark, G. (1996). The animating body: Psychoid substance as a mutual experience of psychosomatic disorder. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 41,353-368. doi:10.1111/ j.1465-5922.1996.00353.x [ Links ]

Clark, G. (2006). A Spinozean lens onto the confusions of borderline relations. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 51,67-86. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8774.2006.00573.x [ Links ]

Colman, W. (2008). On being, knowing and having a self. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 53,351-366. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2008.00731.x [ Links ]

Driver, C. (2005). An under-active or over-active internal world? Journal of Analytical Psychology, 50,155-173. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8774.2005.00520.x [ Links ]

Elias, A. C. A., Ricci, M. D., Rodriguez, L. H. D., Pinto, S. D., Giglio, J. S., & Baracat, E. C. (2017). Development of a brief psychotherapy modality entitled RIME in a hospital setting using alchemical images. Estudos de Psicologia, 34(4),534-547. doi:10.1590/1982-02752017000400009 [ Links ]

Fordham, M. (1993). Notes for the formation of a model of infant development. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 38(1),5-12. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1993.00005.x [ Links ]

Gibeault, A. (2005). Symbols and symbolization in clinical practice and in Elisabeth Marton's film My Name was Sabina Spielrein. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 50(3),297-310. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8774.2005.00534.x [ Links ]

Guggenbühl-Craig, A. (2004). O abuso do poder na psicoterapia e na medicina, serviço social, sacerdócio e magistério. São Paulo: Paulus. [ Links ]

Gusarova, S. B. (2014). Recovery of consciousness: Process-oriented approach. Zhurnal voprosy neǐrokhirurgii imeni N. N. Burdenko, 78(1),69-76. Retrieved from https://www.mediasphera.ru/msph/en/neiro/artcl/VoprosyNeirokhirurgii_2014_01_063_EN.pdf [ Links ]

Harling, M. (1966). Homœopathy: The bridge between psychological and somatic medicine. British Homoeopathic Journal, 55(1),20-22. doi:10.1016/S00070785(66)80024-8

Hartman, D.; Zimberoff, D. (2004). Corrective emotional experience in the therapeutic process. Journal of Heart Centered Therapies, 7(2),3-84. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.467.8398&rep=rep1&type=pdf [ Links ]

Hartman, D.; Zimberoff, D. (2006). Soul migrations: traumatic and spiritual. Journal of Heart Centered Therapies, 9(1),3-96. Retrieved from http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/213128/file-2133485071-pdf/docs/Journal_9-1_Soul_Migrations.pd [ Links ]

Herrmann-Lingen, C. (2017a). Past, present, and future of psychosomatic movements in an ever-changing world: Presidential address. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79,960-970. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000521 [ Links ]

Herrmann-Lingen, C. (2017b). The American Psychosomatic Society - integrating mind, brain, body and social context in medicine since 1942. BioPsychoSocial Medicine, 11(11),1-7. doi:10.1186/s13030-017-0096-6 [ Links ]

Jung, C. G. (2011a). Mysterium Coniunctionis: Os componentes da coniunctio (Vol. 14/1). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Jung, C. G. (2011b). Psicologia do inconsciente (Vol. 7/1). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Jung, C. G. (2011c). Psicogênese das doenças mentais (4a ed.). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Jung, C. G. (2012). Aion: Estudos sobre o simbolismo do si-mesmo (Vol. 9/2). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Jung, C. G. (2018). Sincronicidade (Vol. 8/3). Petrópolis, Vozes. [ Links ]

Kalsched, D. E. (2013). Encounters with "dis" in the clinical situation and in Dante's Divine Comedy. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 33(5),479-495. doi:10.1080/07351690. 2013.815065 [ Links ]

Koss-Chioino, J. (2006). Spiritual transformation, relation and radical empathy: Core components of the Ritual Healing Process. Transcultural Psychiatry, 43(4),652-670. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9744.2006.00785.x [ Links ]

Kradin, R. L. (1999). Generosity: A psychological and interpersonal motivational factor of therapeutic relevance. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 44(2),221-236. doi:10.1111/1465-5922.00085 [ Links ]

Kradin, R. L. (2011). Psychosomatic disorders: The canalization of mind into matter. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 56,37-55. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2010.01889.x [ Links ]

Kradin, R. L. (1997). The psychosomatic symptom and the self: a sirens' song. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 42(3),405-423. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1997.00405.x [ Links ]

Ledermann, E. K. (1967). The patient's experience and the homœopathic drug picture. British Homoeopathic Journal, 56(2),75-80. doi:10.1016/S0007-0785(67)80055-3

Leite, A. C., Júnior, Katzer, T., & Ramos, D. G. (2017). Three cases of hair loss analyzed by the point of view of the Analytical Psychology. International Journal of Trichology, 9(4),177-180. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_106_16 [ Links ]

Machado Júnior, P. P. (2007). O baú dos sonhos adormecidos: a dimensão simbólica da rinite alérgica em um estudo de caso. Boletim de Psicologia, 57(126),89-106. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S000659432007000100010&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Maher-Loughnan, G. P. (1975). Intensive hypno-autohypnosis in resistant psychosomatic disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 19(5),361-365. doi:10.1016/00223999(75)90015-X [ Links ]

Margets, E. L. (1950). The early history of the word "psychosomatic". Canadian Medical Association Journal, 63,402-404. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1821745/pdf/canmedaj00649-0079.pdf [ Links ]

Marlo, H. (2013). Between the worlds-healing trauma, body, and soul: A conversation with Donald Kalsched. Jung Journal, 7(3),117-141. doi:10.1080/19342039.2013.813280 [ Links ]

Meier, C. A. (1963). Psychosomatic medicine from the Jungian point of view. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 8(2),103-122. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1963.00103.x [ Links ]

Mello, J., Filho (2002). Concepção psicossomática: Visão atual. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Mueller, L., Gallagher, R. M., Steer, R. A., & Ciervo, C. A. (2000). Increased prevalence of sensing types in men with cluster headaches. Psychological Reports, 87,555-558. doi:10.2466/pr0.2000.87.2.555 [ Links ]

Müller, M. C.; Ramos, D. G. (2004). Psicodermatologia: uma interface entre Psicologia e Dermatologia. Psicologia Ciência e Profissão, 24(3),76-81. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1414-98932004000300010&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Passos, C. H.; Lima, R. A. de. (2017). A contribuição da calatonia como técnica auxiliar no tratamento da fibromialgia: Possibilidades e reflexões. Boletim de Psicologia, 67(146),13-24. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0006-59432017000100003&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Plassman, R. (1998). Organ worlds: Outline of an analytical psychology of the body. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 18(3),344-367. doi.org/10.1080/07351699809534197 [ Links ]

Prigatano, G. P. (2012). Jungian contributions to successful neuropsychological rehabilitation. Neuropsychoanalysis, 14(2),175-185. doi:10.1080/15294145.2012.10773701 [ Links ]

Proner, B. D. (2005). Bodily states of anxiety: The movement from somatic states to thought. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 50,311-331. doi:10.1111/j.00218774.2005.00535.x [ Links ]

Rafieian, S.; Hosier, S. (2011). Dissociative experiences in health and disease Human Architecture. Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 9(1),89-109. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecture/vol9/iss1/9 [ Links ]

Ramos, D. G. (2006). A psique do corpo: Uma compreensão simbólica da doença. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Redfern, J. (2000). Possible psychosomatic hazards to the therapist: patients as selfobjects. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 45(2),177-194. doi:10.1111/1465-5922.00151 [ Links ]

Ruckmick, C. A., & Warren, H. C. (1926). A schematic classification of general psychology. Psychological Review, 33(5),397-406. doi:10.1037/h0076068 [ Links ]

Samuels, A. (1989). Escolas da Psicologia Analítica. In A. Samuels, Jung e os pós-junguianos. Rio de Janeiro: Imago. [ Links ]

Serbena, C. (2013). Interdisciplinariedade e produção acadêmica em psicologia analítica no Brasil de 2003 a 2008. V Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología XX Jornadas de Investigación Noveno Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del Mercosur, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Retrieved from https://www.aacademica.org/000-054/105 [ Links ]

Sidoli, M. (1998). Hearing the roar. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 43(1),23-33. doi:10.1111/1465-5922.00005 [ Links ]

Sidoli, M. (1993). When the meaning gets lost in the body: Psychosomatic disturbances as a failure of the transcendent function. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 38,175-190. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1993.00175.x [ Links ]

Souza, A. T. C. de; Jucá, A. C. B. (2015). Monomito, individuação e o Fausto: A simbolização como ferramenta psicoterápica transdisciplinar. Arte médica ampliada, 35(4),153-157. Retrieved from http://abmanacional.com.br/arquivo/c9f9d647298d97b5c3ff2bce3d8ebd1b16727c74-35-4-monomito-individuacao-e-fausto.pdf [ Links ]

Tacey, D. (2011). The challenge of teaching Jung in the university. In K. Bulkeley & C. Weldon (Eds.), Teaching Jung (pp. 13-27). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Thibeault, C.; Sabo, B. M. (2012). Art, archetypes and alchemy: Images of self following treatment for breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16(2),153-157. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2011.04.009 [ Links ]

Urban, E. (2005). Fordham, Jung and the self: A re-examination of Fordham's contribution to Jung's conceptualization of the self. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 50,571-594. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8774.2005.00559.x [ Links ]

Urban, E. (2008). The 'self' in analytical psychology: the function of the 'central archetype' within Fordham's model. The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 53(3),329-350. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2008.00730.x [ Links ]

Urban, E. (2006). Unintegration, disintegration and deintegration. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 32(2) 181-192. doi:10.1080/00754170600780356 [ Links ]

Waldron, S. (2008). The impact of trauma on the psyche of the individual using the film Belleville Rendez-vous as an illustrative vehicle. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 53(4):525-541. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2008.00744.x [ Links ]

Whitmont, E. C. (1964). Psychosomatics. British Homoeopathic Journal, 53(4),255-258. doi:10.1016/S0007-0785(64)80045-4 [ Links ]

Whitney, L. (2018). Jung, Yoga and affective Neuroscience: Towards a contemporary science of the sacred. Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, 14(1),306-320. Retrieved from https://cosmosandhistory.org/index.php/journal/article/viewFile/693/1177 [ Links ]

Wiener, J. (1994). Looking out and looking in: Some reflections on "body talk" in the consulting room. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 39,331-350. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1994.00331.x [ Links ]

Wolff, H. H. (1971). Basic psychosomatic concepts. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 47,525-532. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2467248/pdf/postmedj00344-0007.pdf [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Iris Miyake Okumura

Departamento de Psicologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná

Rua Alfredo Bufren, 50, sala 102, Praça Santos Andrade, Centro

Curitiba, PR, Brazil. CEP 80020-240

E-mail: iris.okumura@yahoo.com.br

Submission: 15/02/2019

Acceptance: 15/04/2020

Authors notes

Iris M. Okumura, Postgraduate Program in Psychology, Federal University of Paraná (UFPR); Carlos Augusto Serbena, Postgraduate Program in Psychology, Federal University of Paraná (UFPR); Maribel P. Dóro, Hospital Complex of Clinics, Federal University of Paraná (UFPR).