Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.23 no.3 São Paulo set./dez. 2021

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPCP13276

10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPCP13276 ARTICLES

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

Family, religion, and sex education among women with vaginismus: a qualitative study

Família, religião e educação sexual em mulheres com vaginismo: um estudo qualitativo

Familia, religión y educación sexual en mujeres con vaginismo: un estudio cualitativo

Ana Carolina de M. Silva ; Maíra B. Sei

; Maíra B. Sei ; Rebeca B. de A. P. Vieira

; Rebeca B. de A. P. Vieira

State University of Londrina (UEL), Londrina, PR, Brazil

ABSTRACT

The diagnosis and treatment of vaginismus are complex, involving biopsychological factors and insufficient etiological assessment. For this reason, we discuss the aspects implicated in vaginismus concerning religion, family, and sex education from the perspective of women affected by vaginismus. This qualitative, exploratory study addressed nine women who experienced vaginismus, accompanied by dyspareunia or not. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and analyzed using content analysis. The results are distributed into two categories: learned concepts about sex and searching for knowledge to fill in information gaps concerning sexuality and sexual dysfunctions. Inadequate sex education leads to ignorance, rigidity, and misconceptions, generating insecurity. Thus, it is relevant to instruct and sensitize families, workers, and those in religious contexts regarding a healthy and constructive way to address sexuality while respecting beliefs and values. There is also a need to improve the health care services provided to this population.

Keywords: vaginismus; sex education; religion; family relations; sexuality.

RESUMO

O diagnóstico e o tratamento do vaginismo são complexos porque envolvem fatores biopsicossociais e insuficiente avaliação etiológica. Por conta disso, buscou-se discutir aspectos do vaginismo referentes à religião, família e educação sexual, sob a perspectiva de mulheres que apresentam essa disfunção. Trata-se de um estudo qualitativo, de caráter exploratório, com nove mulheres que experienciaram vaginismo acompanhado ou não de dispareunia. Os dados foram coletados por meio de entrevistas semiestruturadas e analisados a partir da análise de conteúdo. Os resultados foram dispostos em duas categorias referentes às concepções apreendidas sobre sexo e a busca por conhecimento diante das lacunas de informações sobre sexualidade e disfunções sexuais. Percebe-se que uma educação sexual inadequada propicia desconhecimento, rigidez e equívocos, o que gera insegurança. Portanto, é necessário instruir e conscientizar as famílias, os profissionais e os contextos religiosos acerca de formas saudáveis e construtivas de abordar a sexualidade, respeitando crenças e valores. Aponta-se ademais para a necessidade aprimoramento na prestação de serviços em saúde para essa população.

Palavras-chave: vaginismo; educação sexual; religião; relações familiares; sexualidade.

RESUMEN

El diagnóstico y tratamiento del vaginismo son complejos, implican factores biopsicosociales y una evaluación etiológica insuficiente. Debido a esto, buscamos discutir aspectos del vaginismo relacionados con religión, familia y educación sexual, desde la perspectiva de las mujeres con vaginismo. Este es un estudio exploratorio cualitativo con nueve mujeres que experimentaron vaginismo, con o sin dispareunia. Los datos se recopilaron a través de entrevistas semiestructuradas y se analizaron en función del análisis de contenido. Los resultados fueron organizados en dos categorías con respecto a los conceptos aprendidos sobre sexo y la búsqueda de conocimiento frente a lagunas de información sobre sexualidad y disfunciones sexuales. Se percibe que una educación sexual inadecuada proporciona ignorancia, rigidez y malentendidos, generando inseguridad. Por lo tanto, es necesario instruir y crear conciencia entre familias, profesionales y contextos religiosos sobre formas saludables y constructivas de abordar la sexualidad, respetando creencias. También señala la necesidad de mejorar la provisión de servicios de salud para esta población.

Palabras clave: vaginismo; educación sexual; religión; relaciones familiares; sexualidad.

1. Introduction

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, sexual dysfunctions are disorders in the ability to respond sexually or experience sexual pleasure (American Psychiatric Association, 2014). Among these dysfunctions, the genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder stands out, which consists of a combination of vaginismus and dyspareunia, present in the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2002). Its nomenclature and diagnostic criteria were replaced in the most recent edition of the DSM due to the comorbidity and difficulty distinguishing between these two dysfunctions - there is still much discussion regarding the classification and denomination of vaginismus (Özen, Özdemir, & Bestepe, 2018).

Vaginismus is described as an involuntary spasm of the vaginal muscle that interferes with sexual intercourse and is currently understood as an inability to have sexual intercourse through vaginal penetration due to genital and pelvic pain, fear of vaginal penetration, and tension in the pelvic floor muscles (APA, 2002; 2014). In general, vaginismus is considered a penetration disorder, in which any type of vaginal penetration, such as vaginal dilators, tampons, gynecological examination, or sexual intercourse, are painful or impossible (Pacik, 2014). On the other hand, dyspareunia is recurrent or persistent genital pain that occurs before, during, or after sexual activity (APA, 2002).

According to the DSM-5 (2014, p. 482), there are subtypes: "lifelong/acquired" and "generalized/situational". "Lifelong" occurs when a woman becomes sexually active, and "acquired" is when it emerges after a relatively normal period of sexual activity. "Generalized" occurs in any context and "situational", only in specific situations. Additionally, the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2002, p. 557) also considered the etiology due to psychological or combined factors.

Note that the most recent manual indicates five factors that should be considered at the time of its diagnostic assessment, namely: 1. partner; 2. relationship; 3. individual vulnerability; 4. culture and religion; and 5. medical data that may be relevant in the treatment. These factors may impact symptoms differently and are essential for the etiology and treatment (APA, 2014). Considering the DSM-IV, note that there are uncertainties regarding its conception that culture-related diagnostic issues such as inadequate sex education or religion-related rigidity issues could predispose vaginismus (APA, 2014).

According to Batista (2017), the few empirical studies addressing vaginismus report difficulty reaching a diagnosis and determining treatments, not addressing the disorder's etiology. Criticisms to the DSM-5 refer to insufficient attention paid to the etiological assessment, focusing only on the phenomenology (Özen et al., 2018), which can lead to a neglectful diagnosis of vaginismus throughout life, based on one's specific cultural and religious factors (Alizadeh, Farnam, Raisi, & Parsaeian, 2019). Rahman (2018) states that recent criteria generalize some diseases in minor categories, restricting diagnostic and treatment possibilities. Therefore, understanding vaginismus and dyspareunia are subsets of the Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder. Because this terminology is still widely used in recent literature, it was adopted in this study.

Sexual health and functioning are known to be affected by both biological and psychological factors, including socio-cultural factors, reflected on beliefs and religious interpretations of various cultures (Rahman, 2018). Fadul et al. (2018) conducted a study in the Dominican Republic in which they identified psychosocial factors associated with vaginismus in two groups of women: 40 women affected by vaginismus and 80 women not affected, who composed the control group. The authors addressed sexual abuse, negative ideas regarding sexuality due to religious reasons, fear of sexual intercourse, sex education, and rigid/authoritative upbringing. The results found similarities regarding sexual behavior; women with vaginismus were more concerned with losing control over their bodies and situations.

The literature includes many studies addressing vaginismus in the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries, such as Iran (Alizadeh et al., 2019), Turkey (Özen et al., 2018), and India (Vaishnav, Saha, Mukherji, & Vaishnav, 2020), including issues such as unconsummated marriage (Alizadeh et al., 2019; Rahman, 2018), which is frequently related to sexual dysfunctions, especially vaginismus. Rahman (2018) investigated sexual dysfunctions among Muslim women and found that perceptions regarding sexuality and sexual intercourse affect the type of dysfunction these women experience. Painful sexual disorders were more prevalent due to specific concerns with sexuality arising from religious beliefs, such as virginity. It is relevant to understand conceptions regarding sexuality among Brazilian women with vaginismus, mainly because of the few studies conducted in Latin American countries (Fadul et al., 2018).

Brazil is a country whose vast religious plurality has increased in recent years. However, the Christian group, composed of Catholics and Protestants (traditional Evangelical and Pentecostal), still prevails (Alves, Cavenaghi, Barros, & Carvalho, 2017). Both Catholics and Protestants hold conceptions against non-marital sex. However, the Brazilian Catholic tradition has changed and assumed polysemic characteristics, while Protestants, especially Pentecostals, hold a more rigid and conservative stance (Ogland, Bartkowski, Sunil, & Xu, 2010).

Alves et al. (2017) studied the Brazilian religious transition, stating that this phenomenon influences various socio-cultural spheres. Hoga, Tibúrcio, Borges, and Reberte (2010) conducted a qualitative study to investigate the influence of family and religious orientations on the sexual behavior of Catholic women and identified different experiences organized into three categories that emphasize direct (i.e., sexual abstinence) and indirect instructions provided by the priests, especially regarding the behavior of women in daily life. They also highlight varied experiences within the family context, permeated by two extreme upbringing styles: individuals who did not receive any guidance and those who were able to talk openly about sexuality. Additionally, Hoga et al. (2010) addressed women's reactions toward guidance they received, classifying reactions into those who adhered to guidance and those who rejected teachings. Finally, this study highlights the need to provide adequate guidance regarding religiosity, sexual and reproductive health.

In addition to religion, sexuality and sex education permeate the family, school, and social contexts. Regarding the family context, Pereira (2014) states that the focus is on dating and the consequences of sex; while at school, priority is given to preventive and biological aspects. Hawkins (2016) found a relationship between women's sexual functioning and sex education, which shows that knowledge is related to sexual health, enabling improved performance in terms of desire, lubrication, satisfaction, and pain.

Note that studies addressing sexual health and dysfunctions contribute to improved approaches on how to disseminate knowledge, promote preventive measures, and implement treatments, as proposed by Pereira (2014, p. 13): "elucidating people's conceptions and which discourses are at the basis of their conceptions, is intended to think about possibilities of practice". Therefore, this study aimed to discuss the aspects implicated in vaginismus that refer to religion, family, and sex education from the perspective of women with vaginismus.

2. Method

Qualitative studies in the health field enable a deeper understanding of psychosocial aspects, which are not accessible in quantitative studies (Faria-Schutzer et al., 2019). For this reason, this study is characterized as an empirical, qualitative, exploratory study and seeks to deepen knowledge regarding a seldom-investigated subject (Fontanella, Ricas, & Turato, 2008).

2.1 Participants

Nine women currently with vaginismus or who had experienced vaginismus in the past, accompanied by dyspareunia or not, participated in this study. Inclusion criteria were: being 21 years old or older and presenting criteria provided by the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2002) for vaginismus.

The participants were reached through an invitation posted on social media and in the premises of the Psychology Service-School at the university hosting this study. Therefore, an intentional sample was used according to the saturation criterion, i.e., data collection ceases when data become redundant (Fontanella et al., 2008).

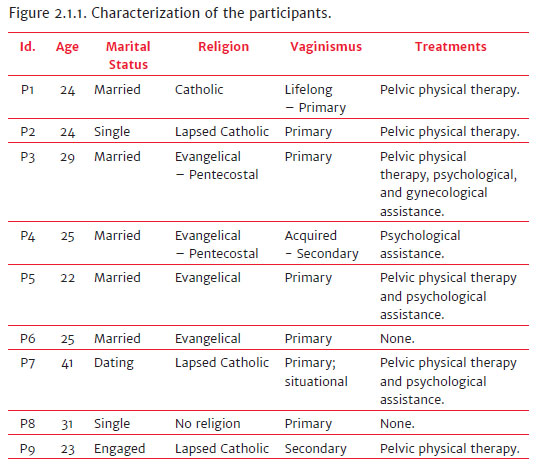

The sample was composed of Catholic, Evangelical, traditional Pentecostal women and women with no religion, most affected by lifelong vaginismus (primary) compared to acquired vaginismus (secondary), as shown in Figure 2.1.1. The participants are identified with the letter P, followed by a random number to ensure confidentiality of data.

2.2 Instruments

A semi-structured interview was developed, based on the main themes reported in studies addressing vaginismus such as religious, emotional, and socio-cultural aspects along with histories of loving relationships and rigid and authoritative upbringing, among others (Fadul et al., 2018; Pacik, 2014; Vaishnav et al., 2020). Semi-structured interviews are intended to explore a new subject using open-ended questions, encouraging the production of ideas and letting the participants talk, elaborate, and make connections freely (Fontanella, Campos, & Turato, 2006). Therefore, the script initially addressed general data such as age, occupation, religion, and marital status and later addressed aspects concerning vaginismus and sexuality. The objective was to understand the experiences of the participants regarding sexual initiation, how vaginismus was identified, their families' attitudes and beliefs concerning sex, and finally, what type of sex education they received, who addressed the subject, their expectations about sex, and how it was addressed at school.

2.3 Procedures

Invitations were posted on social media and in the premises of a Psychology Service-School, including the study objectives, the profile needed, and the contact of the researcher responsible for data collection. The interviews were held with those who manifested interest and met the inclusion criteria. Note that some participants nominated other women to participate in the study; thus, the selection also included an active search.

Individual interviews were held in the places chosen by the participants and lasted 50 minutes on average. Data were recorded and transcribed verbatim after all the participants voluntarily consented to participate and signed free and informed consent forms. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board regulating research addressing human subjects at the State University of Londrina (Opinion report No 2,102,053).

Data were analyzed using the content analysis technique (Bardin, 2011). The categories emerged from a global analysis of the participants' answers content performed by two independent evaluators. Note that there were no categories or precisely pre-determined objectives (Fontanella et al., 2008). Therefore, due to the regional context of this study setting, religious and socio-cultural issues concerning sex education emerged spontaneously in the participants' reports. Thus, these aspects constitute the study objective. Note that this study underwent a methodological assessment on the part of the research group of the Laboratório de Estudos e Pesquisa em Psicanálise [Laboratory of Studies and Research in Psychoanalysis] at the hosting university.

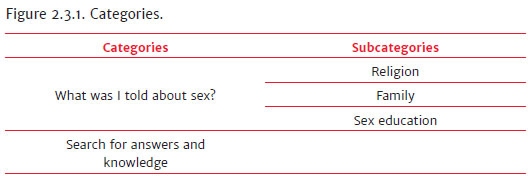

After repeated free-floating and careful readings (Pereira, 2014), the analyses performed by the evaluators were organized according to similarities (Meneses & Santos, 2013) into two categories: 1. What was I told about sex? and 2. Search for answers and knowledge. The first category was subdivided into three subcategories (religion, family, and sex education) to improve the systematization and presentation of results (Figure 2.3.1). The results and discussions are presented together to facilitate visualization of the categories' information and analysis, illustrated with excerpts of reports that corroborate the discussion.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 What was I told about sex?

3.1.1 Religion

Regarding religion, five participants (P1, P3, P4, P5, P6) reported that this aspect strongly influenced their conceptions of sexuality. The remaining reported they either did not have a religion, in the case of P8, or were non-practicing Catholics (P2, P7, and P9), i.e., these participants, as shown by P2's report, sought contact with their spirituality and faith, but did not attend services regularly, as neither did their parents.

The church provides a set of ethical and moral conducts to its members, which influence the development of conceptions and attitudes toward sex (Meneses & Santos, 2013; Rahman, 2018). In general, according to the participants' reports, the perspective and values through which Christianity see loving relationships and sexuality can be organized into the following: prayers to the potential new couple; asking parents permission for dating; relationships with people from the church is preferable; frequent contact with priests to address relationship issues, and chastity until marriage. These issues seem to vary according to the religion, as shown below:

[...] the view of a Pentecostal church is different, very different. I don't know whether you're aware that this is an issue that is much more restricted. It is more restricted, and they look at sins like everything is a sin. So, the very notion of sex, sex is sinful (P3).

Participant (P3) grew up within the Pentecostal religion; however, she decided to attend a traditional Evangelical church after marriage. For this reason, she ponders the different approaches to sex issues. Pentecostals consider sexual intercourse before marriage to be a deviant behavior, adopting approaches that guide devotees toward moral orientation so that devotees either follow piety and holiness or sinful ways (Ogland et al., 2010). Only P3 and P4 reported references to sexuality being sinful. Having this perspective of sex may result in negative feelings, repressing the individual and consequently leading to guilty feelings. In this sense, a participant (P4) reported that, because of her religious upbringing, she initially wanted to have sexual intercourse only after marriage; however, her partner started pushing her to do it when they started dating, and she consented to have sex before being baptized:

After I was baptized, we agreed to not having more sexual intercourse. However, we did it sometimes, and it was okay, but I felt really, really guilty. [...] So we got in a hurry to get married, you know. However, right after marriage, during my honeymoon, I was no longer able to have sexual intercourse. [...]. It was as if I was being raped, it'd hurt, bleed, and I'd cry a lot (P4).

This participant had an active sexual life before her baptism but then developed vaginismus due to the situation. This notion that sex before marriage is a mistake and a sin may be so deeply rooted "that even after sexual life is sanctioned by marriage, one finds it difficult to relax physically or mentally" (Vaishnav et al., 2020, p. 221). Sexual guilt was significantly related to religiosity, spirituality, and religious fundamentalism, like Woo, Morshedian, Brotto, and Gorzalka (2012) showed when addressing Eastern Asian and Canadian women. Therefore, condemning sexuality raised guilt feelings when expressing sexuality; the higher the levels of religiosity, the higher the levels of guilt (Woo et al., 2012).

Sexual guilt mainly arises from being tempted and desire something that cannot be consummated. Meneses and Santos (2013) interviewed Evangelical youths regarding sexuality and found a consensus that, according to the church, the only possible and correct sex activity is after marriage. Sex only after marriage was the aspect of the religious discourse most frequently emphasized by the Evangelic participants, who reported that they had had opportunities to have sex but "stopped" or "refrained" themselves from doing it. P3 considered that feeling tempted by itself was already a sin, causing "much suffering and regret", while others, such as P6, saw it as part of the process, which required constant reaffirmation of her choice. Hawkins (2016) found a relationship between dysfunctional beliefs concerning sex and the perspective of desire being a sin; sex conservative views are associated with these beliefs.

On the other hand, Catholicism has a more plural view, so that none of the participants waited until marriage, and, as mentioned by P1, the church's principles are adapted to one's personal values and context. Values are perceived to vary among individuals as much as among the different religions:

I thought that I had to have sex after marriage, like, that's what I thought a little before I started dating. Then, I opened up my mind and saw that it was nonsense, and I always researched this religious issue and realized that it wasn't like that (P1).

So I put that idea in my mind, but I wasn't really aware, "I won't do this, because..." No, it was a matter of principles, values, you know. It wasn't something I decided and it was okay for me, no, it was forced. So much that it happened what happened (P3).

P1 critically reflected upon the values imposed by religion, while P3 reported it was something she "was not aware of." These decisions "may result from a profound reflection on one's personal and family situation or be an unconscious subordination to values and patterns recommended by the church" (Hoga et al., 2010, p. 713). Thus, whenever providing care to religious women, health workers should verify whether they are aware of their choices and allow them to reflect about them within the health services (Hoga et al., 2010).

Therefore, there is a need to instruct rather than only imposing values and conducts. In this sense, P5 and P6 mentioned the marriage preparation course offered by the church, the only source of information regarding sex and marital life they had. However, even after the course, P5 stated that she had no idea how sex would be, which was a "surprise." This report is in line with the results reported by Meneses and Santos (2013), in which the participants reported that discussions within the church regarding sexuality were shallow and lacked clarifications, mainly because of the taboo surrounding this subject.

3.1.2 Family

When dealing with family upbringing, conservative and rigid values appear, often permeated by a religious context. Sexual education within families was mainly characterized by a lack of dialogue and the imposition of rules, as the following excerpts show:

My mother never talked about sex with me; it was very tense at home. It was a little embarrassing when we watched scenes of sex in soap operas; everyone would be embarrassed. Nobody ever talked to me about sex or any other issues involved in a relationship (P5).

They wouldn't let me go out, anywhere; they were always very rigid (P1).

In addition to the religious issue... my mother was terrified of me getting pregnant or that something would happen. I don't think it was so much about the religion itself. We would date like the way people dated in the old times [...] (P3).

[...] my parents would not let me play with boys, I could not wear skirts, and it wasn't about religion [...]. Nobody would talk about it at home. All my friends had already participated in slumber parties, but I couldn't [...]. It was always like that, but I didn't know why, and nobody ever explained that to me (P8).

Sex is a difficult topic to approach, usually surrounded by embarrassment, not only on the part of parents but on the part of children. Regarding these aspects concerning sexuality, the father figure was portrayed as "serious and strict", while the mother was the "spokesperson" transmitting the father's directives. The only father who addressed this issue was P4's father; talks addressing these topics were usually between mothers and daughters (Hoga et al., 2010). Dialogues were rare, and any reference to this subject was negative and had a punitive connotation, with families not providing any clarification or information. It appears that the families considered that not talking about sexuality would prevent it from becoming real. On the contrary, as stated by P8, lack of information leads to doubts regarding rules imposed without explanations.

In general, the participants' families were afraid of early pregnancy and reinforced that they needed to be careful to avoid a bad reputation. The more religious families were also concerned with "sin and fornication." Both incorporate the notion that if values are not complied with, a woman's image is degraded in social contexts (Hoga et al., 2010).

For Pereira (2014), families fear sexual expression because of potential consequences such as pregnancy, diseases and, in some cases, the loss of virginity. Sexuality is seen as an imminent danger of pregnancy. Hence, to avoid it, families imposed various restrictions such as not getting near boys, going to parties, going out frequently, coming back late at night, sleeping at friends' homes, staying alone with a boyfriend, or wearing revealing clothes.

As a result, the families with conservative values transmit a negative perception of sexuality. In Brazil, a predominantly Christian country (Alves et al., 2017), behaviors and perspectives from the religious sphere are also present in the upbringing of children, even in families that do not attend services regularly. Fadul et al. (2018) verified that an authoritative parental style is more frequent among women with vaginismus than in control groups. Lack of information and clarifications regarding impositions and sexuality result in insecurity, fear, and low self-esteem, leading to questions and uncertainties:

[...] only that it was no longer about my father, it was about me, I had already internalized it. I created a monster in my mind; my parents were so rigid that, like, they'd given me 1, and I'd turn it into ten (P1).

My mother always says that she should have been more relaxed with my upbringing because she thinks I am very uptight with things at home. I don't like to do certain things because I feel I might hurt my parents' feelings (P2).

Because I had this treatment at home, I ended up avoiding everything (P5).

The participants reported they felt "stuck, uptight, and repressed". Upbringing styles based on prohibitions and restrictions, without explanations, lead individuals to grow up afraid of what they can and cannot do, afraid of letting their parents down or not meeting their expectations. Based on consequences and responsibilities, this parenting model leads to the idea that sexuality is wrong, implying negative effects, while a correct behavior would be aligned with the parental and religious discourses (Pereira, 2014). Consequently, some of the participants reported they were not comfortable talking to their parents about sexuality and hid the treatment for vaginismus and the use of contraceptives.

3.1.3 Sex education

Many families expect that sex education is provided in other contexts, such as at the church, in schools, or by health workers (Hoga et al., 2010). Regarding schools, most participants (P1, P2, P3, P7, P8, and P9) reported that this was the only source of sex education they had, a fact illustrated by the following reports:

I only received this information at school. I recall that it was in the 7th grade about diseases and the male and female genitalia, that was it. In high school, they talked about diseases, and instead of showing the cool parts, they talked about the bad stuff, recommending caution and all (P7).

I guess that the school did not approach the subject appropriately. It was impactful, but perhaps negatively impactful somehow. We were 12 years old, and they showed us a video on childbirth. So, it was traumatic, you leave your childhood happy and thinking a stork delivered you, and suddenly you see a huge head coming out (P2).

Sex education provided in the school context focuses on biological aspects, addressing the reproductive system and contraceptives. There is no guidance regarding sexual health or pleasure, and content is provided in a way that may be considered aversive and "traumatic", as the reports show. There is a certain similarity with the parental and religious discourse, as the biological perspective is given and the responsibility with the adverse effects of sexuality is emphasized.

Only addressing the prophylactic aspect of the issue may reinforce several sexual beliefs. At the same time, the transmission of disconnected information regarding sexuality may harm sexual health as much as lack of sexual education (Hawkins, 2016). Most women with vaginismus addressed by Fadul et al. (2018) did not receive any sex education, while more than half were exposed to misconceptions of sexuality due to religious reasons.

Pereira (2014, p. 106) notes that schools use "the scientific discourse to instill concern and fear in the experience of sexuality when focusing only on the prophylactic and hygienic nature of it." The academic milieu can promote the dissemination of content and encourage reflection and critical thinking regarding sex education to reform personal conceptions. However, many deficiencies in the educational process and lack of technical-scientific knowledge impede this form of thinking, and educators end up reproducing popular values and behaviors (Pereira, 2014).

In addition to information received at school, some participants also reported that they obtained information from friends and the media. Each of these contexts exerts a type of influence, disseminating parameters of sexuality:

We did not receive sex education from family, but we watched soap operas, movies. I wasn't alienated from the world, but I thought that sex would be crazy, passionate, like sweeping love (P6).

My friends always warned me it'd hurt a lot and made me fear it (P2).

The reports show that friends provided information regarding sexual intercourse, both from personal experiences and socially constructed myths. On the other hand, entertainment channels disseminate an idealized, stereotyped, and possibly unreachable view of sex, especially in the first sexual attempts.

Generally, sexual problems accrue from cultural and religious beliefs, lack of sex education, or ignorance (Vaishnav et al., 2020). Hawkins (2016) notes that the contexts that most frequently influence sexual beliefs are the schools and friends; the school context reinforces beliefs, and friends prevent dysfunctional beliefs.

These influences - family, religion, friends, and the media - affect one's conceptions regarding sexual intercourse and sexuality, while the interpretation and attitudes toward sexual behavior seem to contribute more to dysfunctions than religiosity (Rahman, 2018). Therefore, sex becomes surrounded by expectations and uncertainties. The participants reported that they consider sex a taboo, something "ugly", "dirty", "forbidden", that causes pain; at the same time, they hold social stereotypes in which sexual intercourse is something simple, rapid, easy that everyone does.

The participants show an ambiguous view that is linked to several doubts. Inappropriate sex education reinforces unreal sexual expectations about how, when, and what should happen, and these are the main reasons these individuals experience sexual problems (Vaishnav et al., 2020). Regarding sexual dysfunctions, vaginismus has an unknown etiology (Pacik, 2014; Batista, 2017). However, studies report correlations between dysfunctional beliefs and negative attitudes toward sex, genital aversion, restricted family upbringing, religious education, cultural and family stigma, fear of the (first) penetration, chastity, fear of becoming pregnant, sex only after marriage, anxiety, fear of potential pain, of gynecological examination, and lack or inappropriate sex education (Alizadeh et al., 2019; Fadul et al., 2018; Özen et al., 2018; Pacik, 2014; Rahman, 2018; Vaishnav et al., 2020).

Most authors also considered trauma from childhood, such as sexual abuse (Özen et al., 2018; Pacik, 2014; Rahman, 2018; Vaishnav et al., 2020). However, Fadul et al. (2018) verified that most studies addressing this possibility do not provide statistically significant data correlated with vaginismus, as reported by the DSM-5 (APA, 2014). Only P3 reported sexual abuse in this study, which she partially attributed to her repressed attitude toward sexuality.

Hence, even though these feelings, such as aversion and anxiety related to sex, might be considered individual factors, the impact of cultural and social demands in the formation of these feelings should not be ignored (Alizadeh et al., 2019). Analysis of the reports showed similarities, especially between the family and religious discourses, in which sexuality is seen from a sacred perspective. While the school provides a biological view of sexuality, it sometimes indirectly reinforces the family and religious discourses through comments or "jokes" emerging from the educators' personal experiences (Pereira, 2014). All these expectations and information regarding sexuality contribute to a singular and personal image of sexuality full of aspirations and uncertainties.

3.2 Search for answers and knowledge

When faced with vaginismus, the participants experienced many doubts, questioning whether it was actually a problem or a result of inexperience and the natural difficulties of the sexual initiation process. Confusion was intensified when their expectations did not correspond to reality. So they talked to priests, relatives, and health workers, seeking information and counseling, as the following excerpts show:

You end up talking to people who say things like: "try to hold on", and you think to yourself, "I want to do it", so you hold on, breath deeply, try it, but it doesn't work (P6).

The gynecologist didn't pay much attention, like, not that he didn't pay attention, but he said, "keep trying, it's normal" (P2).

At this point, I had already talked to the priests, they knew other histories of vaginismus in the church, and there are a lot. [...] they thought that it could be some other problem, because it was the first sexual intercourse and we were not used to it [...], and I talked to my physician, and she said, "no, it is okay, it is just a matter of relaxing (P5).

I went to talk to my mother, and she also said that it took her a month to consummate it, so I said, "oh Gosh, one month", and she said that it was because of my inexperience [...] After one month, I hadn't been able to do it and went to a physician, and she said, "I won't even examine you because it's normal; I see many couples like you. I'll tell you, if you don't pull yourself together and stop acting like a baby, you'll lose your husband" (P3).

The preconception that sexual initiation is painful and difficult intensifies uncertainties and may influence fear of penetration (Pacik, 2014; Vaishnav et al., 2020). These women doubted to what extent the pain they experienced was expected, while close people and authorities said that what they felt was "normal", so in these cases, reaching a diagnosis and treatment may take some time or even never happen. Fadul et al. (2018) found that painful sexual intercourse (dyspareunia) was an experience that both the control group and the women with vaginismus experienced, even more frequently in the control group. Additionally, the participants reported that they had never mentioned it to their physicians because they believed pain was inherent in sexual intercourse. This piece of information shows how previous socially constructed conceptions may harm sexual health.

Regarding the performance of health workers, it became apparent there is a gap in the training of these professionals. According to the reports, instead of providing information, the physicians reproduced the same discourses of these women's families and friends, using a non-scientific, popular discourse. When health workers disqualify a patient's symptoms, they prevent this patient from getting proper treatment, confirming that vaginismus is a condition difficult to diagnose and treat (Batista, 2017). So these women "suffer in silence" (Rahman, 2018, p. 541), and there is no possibility to dimension the actual prevalence of this dysfunction (Alizadeh et al., 2019).

Pacik (2014) discusses the training of gynecologists, noting that there are gaps in higher education and medical residency, rendering these physicians unable to diagnose or treat vaginismus. The author developed a table named "what patients do not want to hear (condescending observations)" (Pacik, 2014, p. 1616), i.e., depreciating discourses, similar to those reported by most of this study's participants (except by P8). Humiliating comments harm the patients' self-esteem and make them avoid going to the gynecologist, considering they cannot undergo gynecological examination or have sexual intercourse, even after having "relaxed and stopped acting like a baby", as the professionals suggested.

Given this situation, doubts and search for answers remained, and most of the participants searched the Internet and found information on their own (P1, P3, P4, P5, P9). They also found recommendations from other patients regarding treatments with a dilator and pelvic physical therapy. The remaining were diagnosed by medical professionals, such as P2, who, after a while, returned to the same physician and was finally diagnosed; while P6 needed to find another gynecologist. P8 was the only participant diagnosed by a physician in the first consultation, who asked for exams and screened her history and symptoms. The moment in which they discovered their condition is illustrated by the following excerpts:

I went from one professional to another who did not know very well what vaginismus was. I've reached the diagnosis myself. I took the articles and said, "look, I guess I have this condition" (P3).

So like, we realize that the workers do not... there are some gynecologists who don't even know this condition exists (P1).

I'd never heard about it. [...] then, I saw a post on Facebook; when I saw it, I thought, "wow, this is my salvation" (P9).

Then, when I went to the gynecologist, I'd never had a Pap smear because I couldn't do it either. I started sweating cold, and the physician understood it right away and told me [...], he explained to me what it was (P8).

The Internet was the primary source of information for most participants, not only to find out about symptoms but also about sexuality, sex education, and possibilities of treatment. After making such discoveries, the participants experienced relief because they could better understand their situation and contact groups of women with vaginismus on Facebook. However, the safety of online information remains an issue, because the participants may end up considering online information more reliable than medical knowledge. In the case of the women interviewed here, much of the information they collected was coherent and led them to good professionals; however, online sources may lead to misleading information and terrify people more than provide information.

Nonetheless, these channels are an important source of information and offer the possibility of connecting individuals to professionals who actually provide reliable information, especially when the Internet is so linked to daily life, with so many online courses addressing female sexuality. However, should social media and the Internet be the primary source of safe information concerning sex education and dysfunctions among women? It seems disturbing that social media does a better job supporting women with vaginismus than health workers, friends, educators, or families, and women have to wait until adulthood to discover a dysfunction and finally receive appropriate answers.

Thus, opportunities to discuss sex education contribute to sexual health to the extent that these positively influence the development of appropriate and flexible conceptions, promoting "good and satisfactory sexual functioning, which are public health issues as much as risky sexual behavior" (Hawkins, 2016, p. 28). Fadul et al. (2018) highlight the importance of gynecologists to be attentive to the high incidence of pain during sexual intercourse, implement preventive measures, and decrease its impact on patients' health. Considering that vaginismus is a multidimensional condition (Batista, 2017), physicians, physical therapists, and psychologists play an essential role in this complex biopsychosocial process.

There are many effective treatments, such as the use of dilators, physical therapy, biofeedback therapy, sexual counseling, and psychotherapy (Pacik, 2014), in addition to couple therapy and psychoeducation (Vaishnav et al., 2020). In addition to their respective specificities, each treatment works toward improving self-esteem, self-confidence, and well-being (Batista, 2017). Batista (2017) notes that, in addition to physical therapists applying techniques, they need to collect detailed anamnesis, provide information and educate patients regarding anatomy, physiology, and body awareness, to improve their self-knowledge. Some of the participants (P1, P4, P6, P8) were or are still afraid of seeking treatment, while physical therapy is more frequently sought (P1, P2, P3, P5, P7, P9) than psychological assistance (P4, P3, P5, P7).

Therefore, understanding patients holistically is vital for workers to plan the most appropriate treatment to their particularities. Hoga et al. (2010) consider that guidance concerning sexual health should not be standardized; instead, it should consider and respect religious beliefs to promote ethical and quality care. For this to happen, one needs to address preconceptions and consider all the factors in the process, both physical and biological, and personal experiences.

Therefore, the way education is incorporated in an individual's history and how it will influence this individual is very particular. For this reason, treatments should include an investigation of the individuals' history and background in order to decrease negative attitudes toward sex, addressing myths and misconceptions, and clarifying conceptions regarding sexuality (Vaishnav et al., 2020). The conclusion is that patients are not supposed to fit in traditional sex education; instead, health programs should understand the particularities of each population to provide care that is relevant and significant (Hoga et al., 2010), rather than only reinforcing what has been established.

There are gaps in sex education in general, considering that even health workers and educators lack appropriate training to perform this task. Sex education in schools, within the family, and in religious contexts is based on popular knowledge and conservative values, taking a normative perspective, diverging from appropriate concepts of sexuality (Pereira, 2014). Studies such as this, seeking to characterize the cultural sphere and its influences, are relevant as they enable an approach focused on the particularities of a given population, improving the quality of health services, and sensitizing people regarding the topic (Rahman, 2018).

Even though both physical and emotional support is essential (Pacik, 2014), few studies focus on the role of psychologists in dealing with sexual dysfunctions such as vaginismus, in addition to a lack of data on sexual dysfunctions in general (Rahman, 2018). This current context shows a need for more studies, especially addressing the Brazilian population, to investigate the particularities of vaginismus, considering that most studies and references regarding it are from Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries.

This qualitative study presented family and religious aspects and sex education related to vaginismus, addressing an intentional sample of patients. Limitations include the fact that the results were not compared among women submitted to the same social, educational and religious standards but not affected by vaginismus. Therefore, this study was not intended to associate such aspects as the cause of vaginismus, because, as previously mentioned, the etiology of this sexual dysfunction remains unknown (Pacik, 2014; Batista, 2017). However, these findings enabled discussing some social and cultural factors that women with vaginismus may share, impacting how they experience such a disorder.

In this sense, this study has exploratory relevance, given a lack of Brazilian studies in the field and the presentation of a diverse sample in terms of religions, addressing Catholics, traditional Evangelicals, Pentecostals, and atheists. Additionally, the context experienced by women with vaginismus and their conceptions regarding sexuality were described, holding similarities with the results reported by the international literature. Future research is suggested to interview women without vaginismus and compare sex education experiences, also verifying common variables in the lives of these two groups of women as well as differences.

These findings show that inappropriate sex education leads to gaps and a lack of knowledge, generating insecurity and fear. Disseminating information is the best way to prevent and treat this condition; self-knowledge regarding one's sexuality enables demystifying misconceptions and strengthening patients' confidence in the face of fears and uncertainty. Considering sexuality as a taboo makes the whole development process more painful and challenging. For this reason, it is essential to instruct and sensitize families, health workers, as well as those in religious contexts, regarding healthy and constructive ways to address this subject, respecting the beliefs and values of each group in order to decrease the negative impacts on individuals' sexuality.

References

Alizadeh, A., Farnam, F., Raisi, F., & Parsaeian, M. (2019). Prevalence of and risk factors for genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder: A population-based study of iranian women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(7),1068-1077. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.04.019 [ Links ]

Alves, J. E., Cavenaghi, S., Barros, L. F., & Carvalho, A. A. (2017). Distribuição espacial da transição religiosa no Brasil. Tempo Social, 29(2),215-242. doi: 10.11606/0103-2070.ts.2017.112180 [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association (2002). Manual diagnóstico e estatístico de transtornos mentais: DSM-IV-TR. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association (2014). Manual diagnóstico e estatístico de transtornos mentais: DSM-5. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Batista, M. C. S. (2017). Fisioterapia como parte da equipe interdisciplinar no tratamento das disfunções sexuais femininas. Diagnóstico & Tratamento, 22(2),83-87. Retrieved from http://docs.bvsalud.org/biblioref/2017/05/833699/rdt_v22n2_83-87.pdf [ Links ]

Fadul, R., Garcia, R., Zapata-Boluda, R., Aranda-Pastor, C., Brotto, L., Parron-Carreño, T., & Alarcon-Rodriguez, R. (2018). Psychosocial correlates of vaginismus diagnosis: A case-control study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 45(1),73-83 doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2018.1484401 [ Links ]

Faria-Schutzer, D. B., Surita, F. G. C., Alves, V. L. P., Bastos, R. A., Campos, C. J. G., & Turato, E. R. (2019). Seven steps for qualitative treatment in health research: The clinical-qualitative content analysis. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, 26(1). Retrieved from http://www.cienciaesaudecoletiva.com.br/artigos/seven-steps-for-qualitative-treatment-in-health-research-the-clinicalqualitative-content-analysis/17198?id=17198 [ Links ]

Fontanella, B. J. B., Campos, C. J. G., & Turato, E. R. (2006). Coleta de dados na pesquisa clínico-qualitativa: Uso de entrevistas não-dirigidas de questões abertas por profissionais da saúde. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 14(5). Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=281421864025 [ Links ]

Fontanella, B. J. B., Ricas, J., & Turato, E. R. (2008). Amostragem por saturação em pesquisas qualitativas em saúde: Contribuições teóricas. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 24(1),17-27. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2008000100003 [ Links ]

Hawkins, S. G. (2016). O papel da educação sexual e da religiosidade no funcionamento sexual (Master's dissertation). Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal. [ Links ]

Hoga, L. A. K., Tibúrcio, C. A., Borges, A. L. V., & Reberte, L. M. (2010). Religiosity and sexuality: Experiences of Brazilian Catholic women. Health care for Women International, 31(8),700-717. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2010.486881 [ Links ]

Meneses, A. F. S., & Santos, E. C. (2013). Sexo e religião: Um estudo entre jovens evangélicos sobre o sexo antes do casamento. Clínica & Cultura, 2(1),82-94. Retrieved from https://seer.ufs.br/index.php/clinicaecultura/article/view/1541 [ Links ]

Ogland, C. P., Bartkowski, J. P., Sunil, T. S., & Xu, X. (2010). Religious influences on teenage childbearing among Brazilian female adolescents: A research note. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49(4),754-760. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2010.01544.x [ Links ]

Özen, B., Özdemir, Y. Ö., & Bestepe, E. E. (2018). Childhood trauma and dissociation among women with genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14,641-646. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S151920 [ Links ]

Pacik, P. T. (2014). Understanding and treating vaginismus: A multimodal approach. International Urogynecology Journal, 25,1613-1620. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2421-y [ Links ]

Pereira, P. C. (2014). Educação sexual familiar e religiosidade nas concepções sobre masturbação de jovens evangélicos (Master's dissertation). Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, SP, Brasil. [ Links ]

Rahman, S. (2018). Female sexual dysfunction among Muslim women: Increasing awareness to improve overall evaluation and treatment. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 6(4),535-547. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.02.006 [ Links ]

Vaishnav, M., Saha, G., Mukherji, A., & Vaishnav, P. (2020). Principles of marital therapies and behavior therapy of sexual dysfunction. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62Suppl. 2),S213-222. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_19_20 [ Links ]

Woo, J. S. T., Morshedian, N., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2012). Sex guilt mediates the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire in East Asian and Euro-Canadian college-aged women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(6),1485-1495. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9918-6 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ana Carolina de Moraes Silva

Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Departamento de Fundamentos de Psicologia e Psicanálise

Rodovia Celso Garcia Cid, PR-445 Km 380, Campus Universitário

Londrina, PR, Brazil. CEP 86057-970

E-mail: anacarolianams@gmail.com

Submission: April 8th, 2020

Acceptance: March 19th, 2021

Authors' notes: Ana Carolina de M. Silva, Department of Fundamentals of Psychology and Psychoanalysis, State University of Londrina (UEL); Maíra B. Sei, Department of Fundamentals of Psychology and Psychoanalysis, UEL; Rebeca B. de A. P. Vieira, Department of Fundamentals of Psychology and Psychoanalysis, UEL.