Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia Clínica

versão impressa ISSN 0103-5665versão On-line ISSN 1980-5438

Psicol. clin. vol.32 no.3 Rio de Janeiro set./dez. 2020

https://doi.org/10.33208/pc1980-5438v0032n03a06

FREE SECTION

Suicide and social media: Dialogue with clinical psychologists

Suicídio e mídias sociais: Diálogos com psicólogos clínicos

Suicidio y medios sociales: Diálogos con psicólogos clínicos

Tales Vilela SanteiroI; Rafael Franco Dutra LeiteII; Glaucia Mitsuko Ataka da RochaIII

ICoordenador Substituto e Professor Permanente do Programa de Pós-Graduação e Professor Associado do Departamento de Psicologia da Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM), Uberaba, MG, Brasil. email: talesanteiro@hotmail.com

IIGraduando em Psicologia pela Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM), Uberaba, MG, Brasil. email: rafa.francodutra@gmail.com

IIIProfessora do Curso de Psicologia da Universidade Federal do Tocantins (UFT), Miracema, TO, Brasil. email: gmarocha@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

New tools originating from the internet, such as Social Media (SM), offer psychologists complementary methods for psychological treatment and counseling. This study aimed: (a) to comprehend the views of clinical psychologists regarding online professional counseling, especially when the patient is diagnosed with Suicidal Behavior (SB); and (b) to find out what these professionals think about the ways SM and the internet can contribute to the treatment of patients with SB. This was a descriptive, cross-sectional, qualitative study. The participants were ten psychologists that work in a town in the state of Minas Gerais (Brazil). Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. The sample was defined using the snowball technique, which was terminated when theoretical saturation was detected. The results were analyzed using the thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke, and debated in the light of the contemporary literature focusing on SM and SB. Three thematic axes were formed: Positive and negative aspects of the use of SM in general clinical situations; Positive and negatives perspectives regarding the use of SM when SB is present; and the use of SM in academic and professional environments. The limits and scope of the study are highlighted.

Keywords: suicide prevention; psychologist education; online therapy; qualitative research.

RESUMO

Novas ferramentas advindas da internet, como as mídias sociais (MS), oferecem ao profissional psicólogo métodos complementares de tratamento e acompanhamento psicológico. Este estudo objetivou: (a) compreender a visão de psicólogos clínicos a respeito da atuação profissional on-line, em especial na atenção psicológica a pessoas que apresentam Comportamento Suicida (CS); e (b) averiguar como esses profissionais têm pensado sobre como MS e a internet podem contribuir no tratamento dessas pessoas. O estudo é descritivo, de corte transversal e amparado em enfoque qualitativo. Dez psicólogos clínicos, atuantes numa cidade no interior mineiro, participaram. Entrevistas semiestruturadas foram instrumentos utilizados para coletar dados. A amostra foi definida por meio da técnica de bola de neve e a coleta de dados foi encerrada por saturação teórica. Os resultados foram analisados por meio da análise temática de Braun e Clarke e debatidos à luz de literatura contemporânea que dialoga sobre MS e CS. Três eixos temáticos foram ordenados: Aspectos positivos e negativos no uso de MS em situações clínicas gerais; Perspectivas positivas e negativas frente ao uso de MS quando o CS se presencia; e Uso de MS no meio acadêmico e profissional. Limites e alcance da pesquisa são apontados.

Palavras-chave: prevenção ao suicídio; formação do psicólogo; terapia on-line; pesquisa qualitativa.

RESUMEN

Nuevas herramientas provenientes de internet, como los medios sociales (MS), ofrecen al profesional psicólogo métodos complementarios de tratamiento y acompañamiento psicológico. Este estudio tuvo como objetivos: (a) comprender la visión de psicólogos clínicos acerca de la actuación profesional en línea, en especial en la atención psicológica a personas que presentan Comportamiento Suicida (CS); y (b) averiguar cómo estos profesionales han pensado sobre cómo MS e internet pueden contribuir en el tratamiento de personas que presentan CS. El estudio es descriptivo, de corte transversal y amparado en enfoque cualitativo. Diez psicólogos clínicos, actuando en una ciudad en el interior de Minas Gerais (un estado de Brasil), participaron. Entrevistas semiestructuradas fueron instrumentos utilizados para recoger datos. La muestra fue definida por medio de la técnica de bola de nieve y la recolección de datos fue cerrada por saturación teórica. Los resultados se analizaron por medio del análisis temático de Braun y Clarke y debatidos a la luz de la literatura contemporánea que dialoga sobre MS y CS. Se ordenaron tres ejes temáticos: Aspectos positivos y negativos en el uso de MS en situaciones clínicas generales; Perspectivas positivas y negativas frente al uso de MS cuando el CS se presenta; y el uso de MS en el medio académico y profesional. Los límites y el alcance de la investigación son señalados.

Palabras clave: prevención del suicidio; formación del psicólogo; terapia en línea; investigación cualitativa.

Introduction

Suicidal behavior (SB) can be defined as the intentional act of harming oneself with the aim of ending one's own life, encompassing suicidal ideas and desires, suicidal behavior without death and actual suicides (Schlösser et al., 2014). It results from the complex interaction of biological, psychological, social and cultural factors (Beurs et al., 2015; Botega, 2015; WHO, 2014). Suicidal ideation (SI), included within SB, is about the creation and personal development of the idea of dying, as well as the mental representation of what it would be like to end one's own life. The variability and intensity of the SI have been associated with SB; however, little is known about its consequences (Madsen et al., 2016).

On one hand, issues involving implications related to SI are unclear - after all, not everyone who imagines killing themselves will perform the act -; on the other hand, the number of people who have committed suicide annually is higher than those killed in all conflicts worldwide combined. Reports have indicated over 800,000 annual notifications (one person every 40 seconds) (WHO, 2006, 2014).

Suicide also has continuous and lasting effects on the lives of those close to the person that died (the survivors). It impacts the lives of families, friends and also the community as a whole (WHO, 2014). Despite the fact that this kind of repercussion can be talked about and rationalized academically, truly estimating it is a task that goes beyond the scope of the present, in that when a suicide occurs there is the implication that future generations will have to cope with it (inter- and transgenerational transmission). Self-extermination is a worldwide public health problem (Botega, 2007; WHO, 2014). It is the second leading cause of death between the ages of 15 and 29 in the world. The numbers differ among countries; however, the global suicidal burden is concentrated in the low- and middle-income countries. It is estimated that 75% of all suicides occur in these countries, which includes Brazil (Ministério da Saúde, 2017; WHO, 2014).

Suicide prevention strategies have also been debated and are becoming increasingly prominent worldwide. The WHO considers that world statistics need to be reduced by 10% by 2020 (WHO, 2014). In this scenario, professional care is arguably an important protective factor because, among other reasons, the number of people affected by SB and its consequences is multiplied with each self-inflicted death (Ministério da Saúde, 2017; WHO, 2014). It is believed that the lives of around five or six people close to the deceased are deeply affected emotionally, socially and economically (Botega, 2007; Nunes et al., 2016).

Training professionals to deal with demands arising from situations that permeate SB has therefore a transformative potential in the lives of people and communities. Beyond compliance with public policy, survivors' mental health requires care. In this sense, it is understood that the psychologist has a crucial role to play. These particularities frame the SB phenomenon as highly complex. Creating conditions and space for dialogue seeking strategies for coping with it needs to occur in all social instances. This also includes the various health professions and different levels of healthcare, from primary to tertiary (Maia et al., 2017).

The issue of SB has become imperative today, as the number of reported suicides has increased and is characterized as a worldwide public health problem. Internet-based tools, such as social media (SM) and other information and communication technologies (ICTs), offer professionals dealing with people's mental health, including psychologists, different methods of monitoring and treating those that see suicide as an alternative to deal with their life problems. The arrival of new ICTs is an inexorable and irreversible fact, instigating rapid sociocultural, economic and psychological changes. Despite generations of digital non-native (digital immigrants) mental health professionals possibly "reluctant" to use the resources the internet provides, addressing the underlying transformations has required new theories and ways of thinking about the world, man and human relationships (Lévy, 1995/2011, 1997/2010).

In this text, we emphasize that SM and ICTs are understood as synonymous terminologies, because they designate communication resources that rely on the internet. Through them, patients and psychologists write and/or exchange images and/or audios. Communication between them can thus occur "at different times" (asynchronous communication via email, WhatsApp, Messenger, and such) or "at the same time" (synchronous communication via WhatsApp, Skype, FaceTime, and such). The use of these technologies in the clinic therefore presupposes that their users can interact and dialogue without necessarily being close or synchronized in time (Santeiro & Rocha, 2015). For this reason, the range and limits embedded in the nature of the chosen technology will likely impact the professional relationship in different ways.

All this technological and communicational movement encompasses new ways of designing psychological treatment and prevention processes (Crestana, 2015; Donnamaria & Terzis, 2015; Fortim & Cosentino, 2007; Lemma & Caparotta, 2014; Pimentel, 2017; Pinto, 2002; Pires, 2015; Siegmund & Lisboa, 2015). Furthermore, the processes of university training of psychologists, clinical psychologists and psychotherapists are not unaffected (Machado & Barletta, 2015; Mandelbaum, 2015; Rodrigues & Tavares, 2016; Santeiro et al., 2016; Santeiro & Rocha, 2015). In this sphere of debate, however, situations involving SB have not been object of specific attention.

Regarding the profession of psychologist and its legal framework in Brazil, despite the fact that the situation under consideration is an unstoppable process (Rodrigues & Tavares, 2016), the Federal Psychology Council (CFP) only very recently, in 2018, regulated the provision of psychological services through ICTs, after repealing the first resolution about it, published in 2012 (CFP, 2012, 2018). Within the scope of these documents, the CFP includes all informational and communication mediations using internet access. Therefore, provided that the professional practice does not violate the provisions of the Psychologist's Code of Professional Ethics, psychologists are allowed to provide psychological services performed through ICTs. The services may be considered psychological consultations of different types; the technical supervision of the services are provided by psychologists in the most diverse contexts of activity; and staff selection processes and such may happen synchronously or asynchronously.

Psychologists that use ICTs must register in advance with the Regional Council of Psychology and have formal authorization for it. In the absence of that, they would be committing a disciplinary offence. Among the main points of the latest Resolution that drew attention at this moment is that the care of people and groups in urgency and emergency situations through this technological route is inadequate, therefore providing this service in these circumstances must be done in person (CFP, 2018)1.

Whenever comparisons are made between face-to-face and internet-based monitoring and treatment, advantages and disadvantages will inevitably be noted. Among the advantages of internet-enabled resources, some that have been highlighted are accessibility 24 hours a day, every day of the week and low cost. In addition, privacy and anonymity can be ensured by the professionals, provided that technical and ethical parameters are properly followed (CFP, 2018; Donnamaria & Terzis, 2015; Santeiro & Rocha, 2015). Issues that may also be emphasized include where the subjects live and their difficulties in traveling to the physical place where the monitoring is performed, which impact on the chances of continuing the monitoring or treatment, especially when SB is under discussion (Kramer et al., 2015).

The use of SM in psychological counseling is essential in various situations in which mental suffering is present, when the person needs specialized attention and does not necessarily have it available because the health apparatus that could be used does not always have vacancies available. This kind of mismatch is particularly worrisome when it is known that seeking professional help has the potential to reduce SB, as those that seek help are 50% less likely to attempt suicide than those that do not (King et al., 2015). Similarly, Cox and Hetrick (2017) found evidence regarding the effectiveness of individual psychosocial interventions for the treatment of self-harm, SI, and suicide attempts in children and young adults, with an emphasis on the emerging use of electronic methods.

The use of the internet, SM and electronic devices, in turn, may favor innovations in suicide prevention. Performing interventions with young people, which can take place in real time, and using electronic devices to support parents in conjunction with individual psychotherapy can be helpful resources. In a study that monitored these types of online support, there was a significant increase in the tendency to seek help, talk with family and friends, and seek a mental health professional (King et al., 2015). This type of result was also reported by Kramer et al. (2015), when studying online monitoring in an internet forum where suicide risk levels were high for 5.9% of those investigated. After one year of monitoring, there were small and average changes in the participants' lifestyles, as well as a decrease in depressive symptoms. Madsen et al. (2016), when studying how the internet and SM could help in treating people with SB, concluded that having received online support helped to reduce SI levels.

Monitoring and treatments using online mechanisms can lead to an amplification of clinical methods that seek to reduce IS, suicide attempts and deaths (Beurs et al., 2015). Through this avenue of debate, Mewton and Andrews (2015) demonstrated that levels of SI and depression declined in parallel over time through online cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The prevalence of SI in the study population was reduced from 50% to 27% after treatment, while that of depression decreased from 70% to 30%. It should be noted that these estimates decreased significantly after the treatment, regardless of the geographic location of the patients included in the study.

Christensen et al. (2013) followed 155 users of a national telephone service focused on suicide prevention, who showed high levels of SI. Participants were randomly recruited and agreed to receive six weeks of online counseling, along with weekly telephone monitoring. They aimed to determine whether online CBT with and without telephone support was effective in reducing SI in those who called the service compared to the usual treatment. The results indicated a decrease in the SI over the six-week period. However, even for the groups that had only telephone follow-up, a considerable decrease in SB could be observed one year after the study.

Regarding the tools commonly used in these online interventions, by reviewing previously available data on online treatments and prevention programs for depression, anxiety, and suicide prevention in children, adolescents, and youths, Reyes-Portillo et al. (2014) found that of the 14,001 citations initially found in the PsycINFO, PubMed, MEDLINE, and Web of Science databases, 25 articles included the criteria for internet-based interventions. Among these, they identified nine remote programs, eight of which were internet-based and one a mobile application.

These considerations demonstrate the scarcity of studies regarding the online approach to psychological intervention, which seems to occur more markedly in cases of SB. This finding considers that in Brazil the use of ICTs by psychologists has been in the process of "acceptance" and "incorporation" and also that these resources are professionally limited concerning their use in complex or urgency and emergency situations (according to the wording of Resolution nº 11, of May 11, 2018) (CFP, 2018), as cases of SB can be understood. The scarcity of literature, therefore, may reflect both this recent movement around ICTs, and may indicate that, as in the country in general terms, what is carried out "in the practice" does not achieve the corresponding "academic" divulgation.

Accordingly, the following general study questions were developed and investigated: Are SM and other online resources aspects being considered in the work of clinical psychologists? What do they think about this issue and how have they experienced it in their professional practices? When SB is in focus, have these ICTs been incorporated into the care provided to their patients?

In the outlined scenario, the aims of this study were: (a) to comprehend the view of clinical psychologists regarding online professional practice, especially in the treatment and/or psychological counseling for people who manifest SB; and (b) to find out what these professionals think about how SM and the internet can contribute to treating these people.

Method

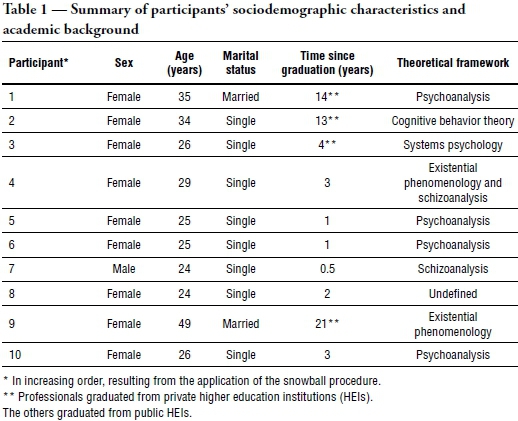

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional, qualitative study (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Yin, 2016). Participants were 10 clinical psychologists, aged 24 to 49 years, mostly single (8) and female (9), having from 6 months to 21 years since graduation, from public higher education institutions (6), working in private practice (9), all in a medium-sized city in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil (Table 1).

Individual semi-structured interviews were used for data collection. This occurred after a pilot study was conducted with two professionals, intentionally chosen due to both of them being university professors and conversant with clinical processes and training of clinical psychologists, working for 30 and 39 years. From the indication of one of these, the snowball procedure was followed, which characterizes the sample of this study as non-probabilistic (Vinuto, 2014; Yin, 2016).

The interviews lasted an average of 30 minutes each and took place in the participants' work environments between March and June 2018. They were audio-recorded and fully transcribed, and were terminated when theoretical saturation was observed (Fontanella et al., 2011). Theoretical saturation was found after the eighth interview had been completed and analyzed. However, according to the snowball procedure, the time since graduation from the third interview reached a maximum of four years (Table 1), indicating a profile of young professionals that "experienced" the process of arrival of ICTs since childhood (digital natives). For these reasons, it was decided to reconfigure the referral process and access a new key informant who had a longer time since graduating and was also a digital immigrant (Participant 9). This measure sought to minimize bias in the constitution of the sample. After this occurrence, it was noted that the theoretical saturation had been reached after the 10th interview had been performed and analyzed.

The data set was evaluated, seeking to apprehend the multidimensional character of the focused phenomena through the thematic analysis method of Braun and Clarke (2006). This method allows patterns within the data to be identified, analyzed and reported, organizing and describing them in detail.

In short, the thematic analysis consisted of six phases: (1) familiarization with the data (immersion in the data through active and repeated reading); (2) generation of initial codes (search for outstanding data characteristics, or semantic or latent content, which is achieved through systematic work with the data set, giving full and equal attention to each item, identifying interesting aspects that may form the basis of repeated patterns); (3) search for themes (analysis of codes considering how different codes can combine to form a comprehensive theme); (4) review of the themes (refinement - review of the data and validation of individual themes in relation to the set - and selection of themes to be used, thus obtaining the main themes around which the research results revolve); (5) definition and naming of the themes (identification of the "essence" of the subject of each theme and determination of what aspects of the data each theme captures); and finally (6) production of the report (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

The establishment of the thematic axes was done by consensus among the researchers. The data, after thematic ordering, were analyzed in the light of debates that the specialized literature has been presenting about SM and SB (CFP, 2012, 2018; Christensen et al., 2013; Cox & Hetrick, 2017; King et al., 2015; Kramer et al., 2015; Madsen et al., 2016; WHO, 2006, 2014, among others).

The main project that led to this study is entitled "Social media and formation of psychologists in clinical and health processes". It was approved under Authorization nº 706.786 (CAAE 26870314.8.0000.5083) by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Goiás. Therefore, all ethical procedures were duly considered.

Results and discussion

The results will be presented in accordance with the aims of the study, listing first how, from the statements, the professionals have been dealing and thinking about SM in their practice, in general. Next, after this contextualization of the work mediated by ICTs has been contemplated, the findings will focus on issues involving phenomena orbiting SB. As will be seen in this article, this thematic "separation" between "SM in general and focused on SB" will not always be possible (especially in Thematic Axis 3), because the participants' narratives migrated from the general experiences they had in the field of ICTs to the specifics containing the SB in a "continuous" way. This choice was made following what Braun and Clarke (2006) envisage as identification, codification and analysis that reports on a particular aspect of the data set (theoretical thematic analysis, deductive in nature and focused on the semantic level - aligned with essentialist/realistic epistemology).

Thematic Axis 1: Positive and negative aspects in the use of SM in general clinical situations

Eight professionals described the possibility of using SM as tools in their clinical practice as positive, not for the treatment itself, but particularly appropriate when face-to-face care would not be possible. The other two participants reported choosing to avoid including SM in their work because they were not comfortable with it and they indicated that, if they did make use of it, they needed to establish stricter psychologist/patient boundaries. Crestana (2015), when discussing the possibility of online therapies, observed something similar in his study. Of 21 respondents, 19 had a positive feeling about these technologies and the remaining reported not having formed an opinion and did not highlight inherently negative aspects.

The question about the use of SM in the work of the psychologist showed that eight out of ten professionals use SM as a means of dissemination and contact with patients. These participants demonstrated sympathy and comfort when using ICTs with regard to questions related to the first contact with patients, about how they do their "advertising" in certain spaces, aiming to reach the target audience of their work. One of them reported that "[…] The use of social media has been positive for me as a newly graduated psychologist, as most of my patients today find me because they've seen a post related to my work on Facebook or Instagram" (Participant 7). This narrative illustrates how SM can go beyond the entertainment dimension, the usual function in non-professional situations, while optimizing possibilities of inclusion in the labor market and the visibility of the professional for potential patients.

Three of the eight psychologists who had investigated the possibility of adopting SM in their practices indicated that this helps to overcome geographical distances between them and those that seek them. In other words, it facilitates the continuity of psychological monitoring in cases in which the person has to relocate, is traveling, or even when they are in a situation where care is needed and a face-to-face meeting is impossible. This aspect was also contemplated in the study by Kramer et al. (2015) and in the CFP Resolutions (CFP, 2012, 2018). In four statements, experiences of continuity in the psychotherapeutic monitoring of patients were emphasized, precisely through the support provided by SM. This occurred mainly when patients moved out of the city or would have to spend a long time away, in situations such as vacations. In addition, one respondent even reported continuing his personal monitoring with another psychology professional through SM, when the person began working in a city other than the one where the work began.

Concerns were mentioned by four interviewees when, in their narratives, they highlighted difficulties that may be generated when using SM: failures in internet connection, unforeseen interventions in the environments in which the transmissions occur, and limitation in the observation of nonverbal behavior of the patient, visible through "crops" of the head and shoulders and/or close-ups of the face. One of the participants said:

[…] as human beings we still need face-to-face care before using the online tool. […] In my line, which is CBT [Cognitive Behavioral Theory] this presence is still important. Not seeing the person, as he or she positions him/herself, may interfere with the care. Maybe [SM] is something to use occasionally. (Participant 2)

Associated with results such as those presented by Mewton and Andrews (2015) and Christensen et al. (2013), the type of statement of Participant 2 raises some questions. Does his narrative contemplate his professional idiosyncrasies and predilections more? And/or does it reflect any difficulties in thinking about or incorporating resources offered by ICTs into his professional daily life, rather than a certain theoretical positioning?

In contrast and complement, another participant commented on counseling experiences that needed to be performed online for consecutive times (because the therapist needed to move from the city), moments in which the patient said: "when we met last week…" and immediately the patient laughed at the situation she herself has generated. In sequence, there were dialogues with his therapist about the way the relationship had been understood as a meeting, "forgetting" the particularity of not being "presential", with this fact becoming a theme to be worked on (Participant 9).

Thematic Axis 2: Positive and negative perspectives regarding the use of SM when SB is present

The accessibility provided by SM was indicated by eight professionals as a facilitator for psychological monitoring. In addition to being able to assist in the client's initial contact with the professional, it favors psychological counseling in critical situations and may allow emergency care. This care, however, particularly in the case of people with SB, was described by four participants from the perspective of an initiative, the purpose of which should be to help the patient in crisis to stabilize and, therefore, indicates the need to have a face-to-face session as soon as possible. This was reported by one of the respondents:

[…] I think this approach is essential at the most immediate moment when the person is in crisis and sends you an audio, a message through WhatsApp. […] define the contact well. When I feel that I should work in session, I tell the person to continue in person at a determined time. (Participant 1)

Regarding perceived ranges and limits in the use of SM in cases involving SB, another respondent said:

I think it goes a little in the direction of what I said about enabling greater contact with this patient, greater professional availability to be with this person. I believe there are challenges in this regard, as face-to-face care allows some resources that are not possible over the internet, but I believe it is an instrument that should be considered. (Participant 5)

Participant 1 pointed out:

One thing is the use of the media, but I also think it's very important to set boundaries, also for the person not to be so dependent on the relationship. Because one of the aspects of the media is ease of access, certain limits need to be established. In one case I had [involving SB], I gave the person my number, even though she didn't call me, because I saw a certain risk.

The previous reports are in line with what was presented in the study by Cox and Hetrick (2017). These authors concluded that the use of the internet, SM and electronic devices allows innovation in relation to suicide prevention, especially when these ICTs are used with young people, many of whom were born after the popularization of the internet, these being digital natives. Following this line of reasoning, Participant 2 said:

I find it extremely positive, as long as it's not just this form. In a patient that is having a crisis, using a resource like this, from what I've read and researched, can be extremely valid. We may not see this need in [name of city] because it is a small town near other urban centers. We get easier access. In larger centers where there is a great distance between the professional and the patient, this could be extremely interesting and used effectively. Also, in a private clinic like here, if the patient goes into crisis at worst he arrives in half an hour. For a social class, it's more accessible. Maybe it's harder in large cities like BH or Ribeirão Preto.

The interviewees' reports concern the use of ICTs in crisis-focused interventions for people who are face-to-face patients. If we consider SB and SI as urgency and emergency situations and the most recent CFP Resolution (2018), counterpoints to the type of care under discussion may be noticed, considering that it is recommended, in Brazil, that psychologists do not treat patients in these situations through ICTs. Because of these subtleties that may exist in the everyday professional practice, which could cause a crisis between the professional that attends to a particular case and what a professional council regulates generically, there are distances that need to be properly weighed, especially regarding the benefit for the patient in a vulnerable situation. Therefore, the questions that seem to arise in cases such as this are: In people that manifest SB and SI, should the care through complements offered by ICTs occur with patients that the professional has or does not have any previous relationship with? What about in situations where the professional and the patient have or do not have a minimally established and/or solid therapeutic alliance?

What are the limits of SM, considering the severity of SB? What harm could be caused by not using SM, considering the severity and high rates of suicide reported today? Following this line of debate, we return to the document produced by the WHO (2014), which states that suicide is the second leading cause of death among people aged 15-29 years. When we consider that this age group is known to use SM in their daily lives, and that they do so "naturally", what harm can be caused by not using these ICT resources with them?

Returning to the reporting of data, for respondents the use of SM seems to make their work easier, with it being up to them to determine limits and analyze intrinsic risks. One of the participants, on the other hand, articulated the issue of differentiated care for patients with specific conditions, such as psychiatric and SB patients, in which the use of SM may not be considered the best choice.

One psychologist emphasized a negative and inconstant aspect of the data set, which, however, constitutes a theme of significant relevance in clinical processes, related to the particularities involving the patient-therapist dyad:

I think it [the use of SM in cases of SB] puts you with the patient very quickly and directly, which allows you to offer care very quickly, although it depends on a sensitive position of the psychologist regarding how to provide it so that the patient does not use it as a means of manipulation. (Participant 6)

A question presented by a participant that adds to what has been exposed refers to cases of crisis of patients who display SB: would the psychologist miss "being there" (in person) at a time when the person needed it? In addition, the same interviewee pointed out that such a change of contact from "personal" to "online" could inhibit the contact of the psychologist with the patient's family and thus reduce the quality of the treatment. As the participant said, "[…] I don't see myself counseling anyone via Skype, for example, not at all. Because you will not really be available to the person at a time of crisis, when they need you." (Participant 7)

These types of professional reports are in line with debates that focus on the limits and disadvantages of using ICTs in SB cases. For example, Pinto (2002) highlighted difficulties related to online counseling, such as the screening for nonverbal cues, changes in voice intonation (low, high, among others), the perception of silences and pauses (prolonged or brief), as well as possible structural difficulties related to internet connection problems or even unfamiliarity with the tools used by the psychologist. However, with the advancement of ICTs since the time Pinto published his study, it seems productive to question whether there have been improvements in the approximately 17 years to the present day that overcome at least part of those concerns. Naturally, the answer to this kind of questioning would be positive, although, in this situation one must consider differences in the quality of online transmission depending on where they take place. Disparities in the quality of the infrastructure for the use of ICTs, paradoxically, would hinder access of people who demonstrate SB and live far away from large urban centers and lack medical and psychological care.

One of the professionals, when talking about methods of intervention with people who display SB, stated that there would be no generalist approach to dealing with this issue. The main point to be considered by him would revolve around the way the professional would deal with the suffering of the subject. Another professional stressed the need to increase the number of sessions and to have greater availability in the way the psychologist would use SM with a patient with differentiated conditions such as SB. In the latter case, the professional could agree to receive messages if something critical was reported by the patient and the need for immediate dialogue arose, characterizing through these more punctual and timely care. This availability was described as positive, as the client may start to show satisfaction for the immediate support available through SM, such as WhatsApp, whereas the professional would have the chance to perceive what the patient felt at the time of making contact online, while favoring the session, working face-to-face on issues brought up by the patient in the digital environment. Fortim and Cosentino (2007) came to similar conclusions. They stated that the online orientation could only be characterized as a gateway, the purpose of which is to evaluate and refer the person to face-to-face care.

Thematic Axis 3: Use of SM in the academic and professional environment

All the participants reported the existence of few discussions in academic circles about the use of SM in psychological monitoring. This was also noted in cases where SB is present. One of the points that would characterize the exception is the use of SM in limited psychotherapeutic interventions (different from those that occur in the medium- and long-term), which has been contemplated in some scientific events, albeit incipiently. On the other hand, debates about SM in non-academic training and professional environments, such as study groups and/or supervisory situations, have been presented. The discussion about the use of these resources in the monitoring of people with SB has been, by contrast, less visible. This seems to occur because this is a more specific topic, referring to a theme still little explored in its ethical implications, limits and potentialities, as the literature review presented at this time showed.

The use of SM in psychological treatments and also with people that manifest SB has been little discussed, which, in part, also seems to be supported by the fact that this topic is seldom explored in academic-professional training environments, as mentioned by the participants. Social Media resources are seen as common in their private lives; however, SM has been included in their professional practices without the existence of corresponding training and/or clarification of the guidelines emanating from their own professional category. The concern involved in the use of SM in the work as a clinical psychologist, as discussed earlier, may be linked to the lack of preparation provided by the educational institutions from which they graduated. Nine professionals stated that they had no training on how to use SM in their professional practice, not even in questions related to first contact with the patient. One of the participants said:

I have already used the media, the social networks, as a way of disseminating my work, as a way of promoting debates on topics that I consider important. […] I don't think my training built anything along those lines. I think the topic was not addressed. Even in our practice it is something that engenders a certain distress when we start, because these are things we do not cover in our training. For example, today it is very common for patients to contact us through WhatsApp. Today the professional psychologist is a little more accessible, because of all these networks, Facebook, WhatsApp; in a certain way we are more exposed. So how do we deal with these networks? I think it was not a theme addressed in my training, so these are things that we have to build later, in the practice, searching, getting supervision. (Participant 5)

Participant 6 complemented:

[…] I think the way the [undergraduate] course takes us to a sensitive place, always evaluating things, leads us to use technology wisely. I am in favor of using these technologies for specific situations, not for their own sake. More as an option and a tool in emergency situations, such as when something serious happens to the person and she urgently needs a session and there is no way she can be with me there at that time, or she is in another city or another country. Or even in danger of suicide, as the research suggests.

This deficit in education does not seem to be due exclusively to when the interviewees got their degrees, given that seven of them graduated within the previous five years (at the time of data collection). This seems to create "uncertainty" when the professional is faced with a need for this type of contact or monitoring, which tends to be achieved through supervision groups and complementary training pursued by the psychologists themselves. Thus, the problem would not be SB in itself, but the very fact of using or not using SM, a phenomenon that is going through a process of gradual and possible assimilation as a tool, along with other techniques already assimilated into the work routines.

In the 2012 resolution, fully in force in the period in which the interviews were conducted (CFP, 2012), psychological services performed by technological means of remote communication were recognized. They should be timely, informative, focused on the proposed theme and should not go against the provisions of the Code of Professional Ethics. The following activities are allowed: developing psychological orientation of different types (limited to up to 20, synchronous or asynchronous, meetings or virtual contacts); performing staff selection previews; applying properly regulated tests; supervising the work of psychologists; and attending clients who are momentarily unable to be attended in face-to-face mode. This indicates that the participants' comprehension of ICT use came from a 2012 resolution that restricted the possibility of online psychological monitoring primarily to focal situations and/or for research purposes. In the updated 2018 version of this document, the idea of long-term care taking place, in addition to research activities, has been better assimilated.

One of the participants said: "[…] I know that CFP's code of ethics has some indications that not all cases can be addressed via Skype, but I don't think it receives the attention it should, precisely because it's such a hot topic" (Participant 5). However, as much as psychologists may acquire new skills related to working with the support of ICTs, their subjective view of them and the way they are dealt with in their formal and informal working environments, for example, through their professional advice and their peers, remain fundamental for us to understand the associated subtleties.

The presence and incorporation of the use of ICTs is a historically recent phenomenon and seeking to understand it in its reach and limits is a process that requires continuous efforts by society, professionals, researchers and institutions. In the process of training and professional practice of the clinical psychologist this is no different. Assessing the possibilities and impacts of these tools on people's mental health care is a necessary and equally imperative measure. As stated in one of the interviews,

[…] It is essential to work on and research this kind of approach, these new tools, precisely because we do not know the impact they can have on the life of someone who has suicidal ideations or who is depressed. […] We must adapt to the media space to identify where the subject is in this whole plot. (Participant 10)

Final considerations

The participants' opinions about the professional performance involving SM in treatment and/or clinical counseling for people, including those who display SB, highlighted inseparable potentialities and limits. In general, we found positions linked to the context of their particular and subjective performance. Accordingly, policies and guidelines of proper conduct for the professional category of psychologists were not covered in the narratives, illustrating two aspects that are not exclusive of each other and that may be in progress: (1) the data collection was performed at a time when professional resolutions covering ICTs were under review, and also the publication of resolution nº 11 of 11 May 2018 overlapped the period in which the data collection took place; and (2) the interviewees' understanding of the role that SM can play in the professional practice and, perhaps more particularly, in the monitoring of cases involving SB is still at an embryonic stage.

In cases of SB, new studies would allow a better understanding of when and how to use SM, so that they remain under evaluation and eventually may be useful in clinical practices that ponder and preserve ethical guidelines, not just those emanating from professional advice. In addition, these initiatives would allow for a deeper comprehension of the repercussions of the use of SM, indications and guidance on when it may be adopted in psychological monitoring in Brazil, with SB being on the agenda. Studies with different methodological designs and samples from those adopted here seem to be promising in this regard.

As questioned by Rodrigues and Tavares (2016), would it be within the scope of a professional council to curb "infringement" to the restrictions it regulates, to the detriment of the integrity of the physical and mental health of patients in vulnerable situations such as SB? If within its scope, what benefits and harm would be in focus, and who would they fall back on? On the professional, the patient? On both? On family members, society? These are some of the questions instigated by the research process and which now occupy a space for reflection and encourage new studies to be developed to clarify them.

Finally, we emphasize that the study aimed to investigate the use of SM in clinical processes involving psychologists and the counseling they can provide by these means when a user of their services manifests SB. Although this approach is being followed at this time, it should be emphasized that coping with suicide and its reverberations requires multidisciplinary collaboration and crosses different levels of healthcare.

References

Beurs, D.; Kirtley, O.; Kerkhof, A.; Portzky, G.; O'Connor, R. C. (2015). The role of mobile phone technology in understanding and preventing suicidal behavior. Crisis, 36(2), 79-82. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000316 [ Links ]

Botega, N. J. (2007). Suicídio: Saindo da sombra em direção a um Plano Nacional de Prevenção. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 29(1), 7-8. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1516-44462007000100004 [ Links ]

Botega, N. J. (2015). Crise suicida: Avaliação e manejo. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Braun, V.; Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

CFP - Conselho Federal de Psicologia (2012). Resolução CFP nº 11/2012. Brasília: CFP. https://site.cfp.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Resoluxo_CFP_nx_011-12.pdf [ Links ]

CFP - Conselho Federal de Psicologia (2018). Resolução CFP nº 11/2018. Brasília: CFP. https://site.cfp.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/RESOLU%C3%87%C3%83O-N%C2%BA-11-DE-11-DE-MAIO-DE-2018.pdf [ Links ]

Christensen, H.; Farrer, L.; Batterham, P. J.; Mackinnon, A.; Griffiths, K. M.; Donker, T. (2013). The effect of a web-based depression intervention on suicide ideation: Secondary outcome from a randomised controlled trial in a helpline. BMJ Open, 3(6), e002886. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002886 [ Links ]

Cox, G.; Hetrick, S. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for self-harm, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in children and young people: What? How? Who? and Where? Evidence Based Mental Health, 20(2), 35-40. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102667 [ Links ]

Crestana, T. (2015). Novas abordagens terapêuticas: Terapias on-line. Revista Brasileira de Psicoterapia, 17(2), 35-43. http://rbp.celg.org.br/detalhe_artigo.asp?id=176 (acessado em 05/03/2019). [ Links ]

Donnamaria, C. P.; Terzis, A. (2015). Atendimento psicológico via internet: Uma experiência com grupos. In: Santeiro, T. V.; Rocha, G. M. A. (Orgs.). Clínica de orientação psicanalítica: Compromissos, sonhos e inspirações no processo de formação, p. 153-174. São Paulo: Vetor. [ Links ]

Fontanella, B. J. B.; Luchesi, B. M.; Saidel, M. G. B.; Ricas, J.; Turato, E. R.; Melo, D. G. (2011). Amostragem em pesquisas qualitativas: Proposta de procedimentos para constatar saturação teórica. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 27(2), 388-394. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2011000200020 [ Links ]

Fortim, I.; Cosentino, L. A. M. (2007). Serviço de orientação via e-mail: Novas considerações. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 27(1), 164-175. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1414-98932007000100014 [ Links ]

King, C. A.; Eisenberg, D.; Zheng, K.; Czyz, E.; Kramer, A.; Horwitz, A.; Chermack, S. (2015). Online suicide risk screening and intervention with college students: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 630-636. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038805 [ Links ]

Kramer, J.; Boon, B.; Schotanus-Dijkstra, M.; van Ballegooijen, W.; Kerkhof, A.; van der Poel, A. (2015). The mental health of visitors of web-based support forums for bereaved by suicide. Crisis, 36(1), 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000281 [ Links ]

Lemma, A.; Caparotta, L. (Orgs.). (2014). Psychoanalysis in the technoculture era. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Lévy, P. (1995/2011). O que é o virtual?, 2ª ed. São Paulo: Editora 34. [ Links ]

Lévy, P. (1997/2010). Cibercultura, 3ª ed. São Paulo: Editora 34. [ Links ]

Machado, G. I. M. S.; Barletta, J. B. (2015). Supervisão clínica presencial e online: Percepção de estudantes de especialização. Revista Brasileira de Terapias Cognitivas, 11(2), 77-85. https://doi.org/10.5935/1808-5687.20150012 [ Links ]

Madsen, T.; van Spijker, B.; Karstoft, K.-I.; Nordentoft, M.; Kerkhof, A. J. (2016). Trajectories of suicidal ideation in people seeking web-based help for suicidality: Secondary analysis of a dutch randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e178. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5904 [ Links ]

Maia, R. S.; Rocha, M. M. O.; Araújo, T. C. S.; Maia, E. M. C. (2017). Comportamento suicida: Reflexões para profissionais de saúde. Revista Brasileira de Psicoterapia, 19(3), 33-42. https://doi.org/10.5935/2318-0404.20170003 [ Links ]

Mandelbaum, E. (2015). Notas sobre a Psicanálise em tempos de algoritmos. Ide (São Paulo), 38(60), 145-159. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-31062015000200012 [ Links ]

Mewton, L.; Andrews, G. (2015). Cognitive behavior therapy via the internet for depression: A useful strategy to reduce suicidal ideation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 170, 78-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.038 [ Links ]

Ministério da Saúde (2017). Suicídio: Saber, agir e prevenir - Boletim epidemiológico. Brasília: Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2017/setembro/21/2017-025-Perfil-epidemiologico-das-tentativas-e-obitos-por-suicidio-no-Brasil-e-a-rede-de-atencao-a-saude.pdf (acessado em 26/03/2018). [ Links ]

Nunes, F. D. D.; Pinto, J. A. F.; Lopes, M.; Enes, C. L.; Botti, N. C. L. (2016). O fenômeno do suicídio entre os familiares sobreviventes: Revisão integrativa. Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem e Saúde Mental, 15, 17-22. https://doi.org/10.19131/rpesm.0127 [ Links ]

Pimentel, A. S. G. (2017). Reflexões sobre a clínica gestáltica virtual. IGT rede, 14(27), 218-232. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1807-25262017000200006 [ Links ]

Pinto, E. R. (2002). As modalidades do atendimento psicológico on-line. Temas em Psicologia da SBP, 10(2), 167-178. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-389X2002000200007 [ Links ]

Pires, A. C. J. (2015). Sobre os "tratamentos à distância" em psicoterapia de orientação analítica. Revista Brasileira de Psicoterapia, 17(2), 11-21. http://rbp.celg.org.br/default.asp?ed=34 (acessado em 05/03/2019). [ Links ]

Reyes-Portillo, J. A.; Mufson, L.; Greenhill, L. L.; Gould, M. S.; Fisher, P. W.; Tarlow, N.; Rynn, M. A. (2014). Web-based interventions for youth internalizing problems: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(12), 1254-1270.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.09.005 [ Links ]

Rodrigues, C. G.; Tavares, M. D. A. (2016). Psicoterapia online: Demanda crescente e sugestões para regulamentação. Psicologia em Estudo, 21(4), 735-744. https://doi.org/10.4025/psicolestud.v21i4.29658 [ Links ]

Santeiro, T. V.; Guimarães, J. C.; Rocha, G. M. A.; Bravin, A. A. (2016). O uso do Facebook por estagiários de psicologia clínica: Estudo exploratório. Revista da SPAGESP, 17(1), 51-64. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1677-29702016000100006 [ Links ]

Santeiro T. V.; Rocha, G. M. A. (2015). Uso de mídias sociais por psicoterapeutas: Problematizando fronteiras profissionais e esboçando diretrizes. In: Santeiro, T. V.; Rocha, G. M. A. (Orgs.). Clínica de orientação psicanalítica: Compromissos, sonhos e inspirações no processo de formação, p. 175-191. São Paulo: Vetor. [ Links ]

Schlösser, A.; Rosa, G. F. C.; More, C. L. O. O. (2014). Revisão: Comportamento suicida ao longo do ciclo vital. Temas em Psicologia, 22(1), 133-145. https://doi.org/10.9788/tp2014.1-11 [ Links ]

Siegmund, G.; Lisboa, C. (2015). Orientação psicológica on-line: Percepção dos profissionais sobre a relação com os clientes. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 35(1), 168-181. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703001312012 [ Links ]

Vinuto, J. (2014). A amostragem em bola de neve na pesquisa qualitativa: Um debate em aberto. Temáticas, 22(44), 203-220. https://www.ifch.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/tematicas/article/view/2144 (acessado em 05/03/2019). [ Links ]

WHO - Organização Mundial da Saúde (2006). Prevenção do suicídio, um recurso para conselheiros. Genebra: OMS. http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/counsellors_portuguese.pdf (acessado em 25/03/2018). [ Links ]

WHO - World Health Organization (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. Geneva: WHO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564878_eng.pdf (acessado em 13/05/2017). [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2016). Pesquisa qualitativa: Do início ao fim. Porto Alegre: Penso. [ Links ]

Recebido em 26 de abril de 2019

Aceito para publicação em 18 de fevereiro de 2020

Este estudo teve como fonte de financiamento o Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação Científica (PIBIC) do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). O relatório final do processo de Iniciação Científica que gerou o artigo foi indicado pela UFTM para participar do 16º Prêmio Destaque na Iniciação Científica e Tecnológica, edição 2018, do CNPq.

1 This caveat is included to clarify that it must be understood that this article is not "defending" the use of ICTs by psychologists in an uncritical or irresponsible manner.