Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia Clínica

versão impressa ISSN 0103-5665versão On-line ISSN 1980-5438

Psicol. clin. vol.34 no.2 Rio de Janeiro maio/ago. 2022

https://doi.org/10.33208/PC1980-5438v0034n02A08

THEMATIC SECTION – REVIEW, ASSESSMENT AND DEVELOPMENT, THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL, IN CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

'So, let me see if I understood': Narratives of couples about their therapeutic process

'Então, deixa eu ver se eu entendi': Narrativas de casais sobre seu processo terapêutico

'Entonces, déjame aclarar esto': Narrativas de parejas sobre su proceso terapéutico

Gabriela Maldonado FarnochiI; Carla Guanaes-LorenziII

IPsicóloga pela Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM) e Mestre em Psicologia pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, da Universidade de São Paulo (FFCLRP-USP). Psicóloga Clínica. Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brasil. email: gabi_maldo94@hotmail.com

IIPsicóloga e terapeuta familiar. Livre-docente pelo Departamento de Psicologia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, da Universidade de São Paulo (FFCLRP-USP). Professora Associada do Departamento de Psicologia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FFCLRP-USP). Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brasil. email: carlaguanaes@usp.br

ABSTRACT

Couple therapy is an important clinical resource and it can progress along different theoretical approaches. Recently, constructionist proposals have been used, focusing on a dialogical understanding of the therapeutic process. This study outlines the understanding of how couples who have undergone couple therapy under a social constructionist orientation narrate their therapeutic process. Six heterosexual couples were part of this study. Twelve open individual interviews were conducted, focusing on significant moments. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed using reflective thematic analysis procedures. Three axes were built, promoting a procedural view of couple therapy: initial motivation; experiences during therapy; and changes achieved. The birth of children, conflicts and the need of dialogue were the reason couple therapy was sought. During therapy, the couples found a safe environment to talk about different points of view. As a result, they were able to develop empathy and build dialogic spaces at home. We conclude that the therapists' participation in the construction of a safe space for dialogue was essential for the good outcomes attained, functioning as a conversational model to be adopted by the couples in their daily life. Therefore, this research showcases the potential of constructionist couple therapy as a resource in contemporary clinic.

Keywords: couple therapy; therapeutic process; social constructionism.

RESUMO

A terapia de casal é um importante recurso clínico e pode ser desenvolvida segundo diferentes linhas teóricas. Mais recentemente, propostas construcionistas têm sido utilizadas, com foco numa compreensão dialógica do processo terapêutico. O objetivo deste estudo é compreender como casais que passaram por terapia de casal sob uma orientação construcionista social narram seu processo terapêutico. Participaram desta pesquisa seis casais heterossexuais. Foram realizadas doze entrevistas abertas individuais, com foco em momentos marcantes. As entrevistas foram transcritas e analisadas por procedimentos de análise temática reflexiva. Três eixos foram construídos, promovendo uma visão processual da terapia de casal: motivação inicial; vivências durante a terapia; e mudanças alcançadas. Nascimento dos filhos, conflitos e necessidade de diálogo motivaram a busca pela terapia de casal. Durante a terapia, os casais vivenciaram um ambiente seguro para dialogar sobre diferentes pontos de vista. Como consequência, puderam desenvolver empatia e construir espaços de conversa no contexto do lar. Concluímos que a participação dos terapeutas na construção de um espaço seguro para o diálogo foi central para os bons resultados alcançados, servindo como um modelo de conversa a ser adotado pelos casais em sua vida cotidiana. Assim, a pesquisa dá visibilidade para o potencial da terapia de casal construcionista como recurso na clínica contemporânea.

Palavras-chave: terapia de casal; processo terapêutico; construcionismo social.

RESUMEN

La terapia de pareja es un recurso clínico importante y puede desarrollarse por medio de diferentes líneas teóricas. En la actualidad, se han utilizado propuestas construccionistas, centradas en una comprensión dialógica del proceso terapéutico. El objetivo de este estudio es comprender de qué manera las parejas que han pasado por la terapia de pareja bajo una orientación social construccionista narran su proceso terapéutico. Seis parejas heterosexuales han participado en esta investigación. Se realizaron doce entrevistas abiertas individuales, centrándose en momentos significativos. Las entrevistas fueron transcritas y analizadas mediante procedimientos de análisis temático reflexivo. Se construyeron tres ejes temáticos, promoviendo una visión de la terapia de pareja como proceso: motivación inicial; experiencias durante la terapia; y cambios logrados. El nacimiento de los hijos, los conflictos y la necesidad de diálogo apoyaron sus búsquedas por la terapia de pareja. Durante la terapia, ellos vivieron un contexto para hablar de sus diferentes puntos de vista. Por consiguiente, pudieron desarrollar una mayor empatía y construir espacios dialógicos en el contexto de sus hogares. Concluimos que la participación de los terapeutas en la construcción de un espacio seguro fue central para los buenos resultados obtenidos, sirviendo como modelo de conversación a ser adoptado en su vida diaria. Así, esta investigación ha proporcionado visibilidad al potencial de la terapia de pareja construccionista como recurso en la clínica contemporánea.

Palabras clave: terapia de pareja; proceso terapéutico; construccionismo social.

Introduction

The interest in producing knowledge about therapeutic processes and their results follows the development of different therapeutic modalities, along different theoretical lines. This concern has also been present in the specific field of family and couple therapy. In addition to recognizing that factors common to other therapeutic approaches influence the production of clinical change, specific characteristics of this type of therapy have also been investigated in the literature (Diniz Neto & Féres-Carneiro, 2005; Davis et al., 2012).

In this article, we focus on couple therapy, a modality of clinical care originating from the 1950s. As shown by Satir (1995), couple care was at first carried out from an individual perspective, with therapy being offered by two different therapists. Changes in the definition of a couple (in addition to an "I" and a "you", there is a "we") allowed important theoretical and technical advances, based on the contribution of different theoretical frameworks, such as psychoanalytical, cognitive-behavioral, systemic (in its different schools of thought) and social constructionist (Féres-Carneiro, 1994; Costa, 2010). Due to our theoretical-methodological approach, we prioritized the description of constructionism, but we were based on the understanding that this framework was nourished by the developments of second-order systemic concepts, which had already been introducing several problematizations in the field of family therapy, such as the vision of the therapist as part of the observant system and the questioning of diagnosis and power and control in the therapeutic relationship (Hoffman, 1985; Anderson & Goolishian, 2018).

The social constructionist discourse entered the clinical field in the 1980s, proposing greater emphasis on language, on the social and historical context, and on the process of reconstructing meanings. Based on the idea of social construction, authors state that what we know as reality is produced relationally, through language (McNamee & Gergen, 1995/2020). Based on this idea, they argue that there are a variety of ways of describing the world, including what means to be a couple, for example. However, the criteria that people adopt in their definitions are constrained by the social and historical context in which they live in. Thus, it is important for a therapist who is sensitive to constructionist assumptions, to focus on how different meanings are produced and relationally sustained, considering the particularities of each context (Gergen & Ness, 2016; Martins et al., 2014).

In the clinical context, the idea of social construction has promoted questions about essentialist and structuralist views about the person (Gergen, 2009), family and couple (Martins et al., 2014), and therapy (McNamee & Gergen, 1995/2020). Human systems are now conceived as linguistic systems, and therapy is now conceived in conversational or dialogic terms (Anderson & Goolishian, 2018). In this way, the therapist's action seeks to promote dialogically structured contexts, favorable to the relational transformation of meaning (Shotter, 2017).

The influence of constructionist ideas in the clinic does not rest on a single clinical method (Gergen & Ness, 2016). Different forms of practice present themselves (collaborative, narrative, discursive, constructionist, relational, solution-focused, among others). Despite their specificities, such practices share common values: the centrality of the client's narratives; the emphasis on the plurality of voices and views of the person and the world; the recognition that people participate in contexts and networks of mutual influence; and the emphasis on generativity (potentials, resources) at the expense of the focus on deficit supported by essentialist frameworks (Gergen & Ness, 2016; Gosnell et al., 2017).

Specifically in relation to couple therapy, Grandesso (2006) explains that it is sought by people aiming to find ways to harmoniously interact with their partner, so that spaces for dialogue are built together and can be taken beyond the clinical practice. According to her, in contemporary times, love relationships are marked by free choice and revolve around discovering what the world of a new love partner is like and the feeling of wanting to experience new emotions. Couple therapy can provide a safe dialogic space where differences can be respectfully examined, allowing for greater insight into each spouse's relationship and needs.

Brazilian and international inquiries have been developed that seek to provide visibility to the way conversations happen in couple therapy under a constructionist or dialogic orientation, and to the factors that seem to contribute to the construction of change. Case studies on couples' therapeutic processes seek to describe how the dialogue promoted in the therapeutic encounter enables changes in the manner of communicating and getting on (Olson et al., 2012), with emphasis on how the quality of the therapeutic alliance contributes to results such as improved communication, increased mutual trust, reduced discussions and joint learning about managing conflict situations (Rober & Borcsa, 2016).

Barbosa and Guanaes-Lorenzi (2015) conducted interviews with couples who underwent social constructionist therapy about their therapeutic process. Among other aspects, the couples valued the open way in which the therapists mediated the dialogue and pointed out that the conceptions about problems went through changes during couple therapy, as each spouse stopped holding only the other accountable for the problem. Changes in daily behavior, established forms of dialogue and interaction were also reported.

Studying her own clinical practice, Grandesso (2011) proposed that her clients lead her in understanding how the reconstruction of meaning happened for each of them in couple therapy. Her clients reported that therapy made a lot of difference in their lives, as they changed their conception of the problem and built new narratives about themselves. For the author, listening to the clients was crucial for her to better understand the therapeutic processes she conducted.

The studies mentioned have in common the appreciation for clients' perspectives and the search for understanding qualitatively the therapeutic processes in couple therapy. This article adds to these studies, starting from a few questions: What motivates couples to seek therapy? How do they experience the therapeutic process? What changes are achieved? How do their experiences relate to the propositions of a constructionist orientation for the couple therapy clinic?

Along these lines, this research aimed to understand how couples narrate their therapeutic process in couple therapy. Specifically, we seek to describe how couples ascribe meaning to the search for couple therapy, the conversations developed in this context and the main changes they attribute to the therapeutic process experienced in a social constructionist orientation.

Methodology

The development of this research was approved by the Ethics Committee (CAAE no. 96711218.5.0000.5407) and the participants voluntarily agreed to participate, documenting their agreement by signing an Informed Consent Form.

Participants were invited to the study through the "snowball" sampling technique, as described by Vinuto (2014). First, we selected a couple with a profile fit for the research within our professional network; then, we followed with the selection of the others from the contact network of this initial couple. In moments when the participants themselves were unable to refer others, we resumed the selection from our own network. Considering this mode of access to the participants, we set up a group of interviewees in which everyone had taken part in couple therapy with therapists who considered themselves sensitive to social constructionist proposals.

Six heterosexual couples took part in the study, five of them legally married and one in a stable union. All names adopted are fictitious, to avoid identification. Participants were over 18 years of age and had undergone couple therapy in the last three years, with the exception of one of them (Couple 6), who was still in therapy at the time of the interview. This couple was referred by a therapist who, upon learning about the research when communicating with the researchers, figured that it could be useful for the couple, favoring reflection on the process they were experiencing in couple therapy, which was offered in the social clinic of a training institute.

Additional information about Couple 5 is also relevant. As indicated in Table 1, Ricardo and Laura had been in a stable relationship for eight years, having experienced a brief separation during that time. Ricardo was divorced and had a daughter from another marriage. Laura was living in a stable union for the first time (i.e., she was legally single). The couple was referred to take part in the research by a therapist from our professional network and, when invited by us, promptly accepted to be interviewed. However, only at the time of the interview did Ricardo mention that he and Laura were getting separated again. They had decided to break up, but chose to continue living together until they could settle down emotionally and financially. Thus, due to this recent change in their relationship status, and because they were still cohabiting at the time of the interviews, we chose to keep their reports as part of the data.

The interviews were open and conducted by the first author of this article, under the guidance of the second. They were designed to provide understanding of how the couples viewed their therapeutic process. To achieve that, we started the interviews by asking them to recall an arresting moment they had experienced (Shotter & Katz, 1996), considering that such moments can happen when there is a dialogic interaction, favorable to the production of new meanings (Shotter, 2017). From these moments, we talked freely about the initial motivations for couple therapy and the changes achieved through it. The interviews were carried out separately with each spouse and were audio-recorded, with an average duration of 40 minutes.

For the analysis of the interviews' transcripts, we used thematic analysis procedures (Braun & Clarke, 2006) articulated with the social constructionist epistemology. We understand, therefore, that our actions in research produce the data, rather than revealing it (Gergen, 2015). That is, we produce themes based on our dialogic and reflective relationship with the material. Moreover, the reports were treated as situated in broader cultural and social contexts, marked by certain discourses and supporting specific narrative constructions (Braun & Clarke, 2020). In this way, we conducted our analysis based on a few steps: (1) we transcribed the interviews, preserving the colloquial language and highlighting emotional tones; (2) we repeatedly read the interviews and created records to highlight common discourses and repertoires that called our attention; (3) we sought to name specificities and similarities across the reports, focusing on the relevance of meanings, and not on their frequency of appearance; (4) we organized the information into themes, which we intentionally named as a way to produce a procedural narrative of the therapy (before, during and after); (5) we built sub-themes and selected, from the set of interviews, some fragments of dialogue to illustrate them; and (6) we produced a narrative text, in which our voice as researchers could appear intertwined with the voices of research participants, in a manner consistent with our epistemological vision.

Results

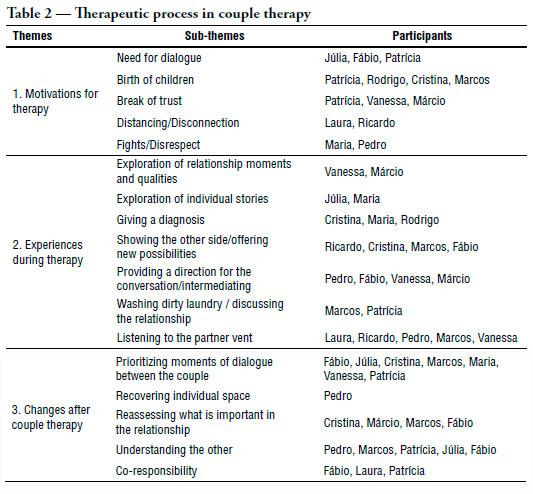

We present, in Table 2, the themes and sub-themes produced through our analysis.

Motivations for therapy

There were many justifications from the participants for seeking couple therapy. Some pointed to the "need for dialogue" as the main motivation for therapy. They hoped to find a space for speaking and listening different from what they experienced at home. Often, they would not find proper moments to have conversations as a couple, to look carefully at aspects of the relationship that need more attention, whether due to work overload, care for the children or other social obligations. The lack of dialogue would end up culminating in conflicts:

Patricia: (…) with a child it's practically impossible, so much so that the last time we went to therapy I had to wake up at 5 a.m., because that's the time we can talk at home, you know? There is no other space for dialogue. (…) I think that this second therapy was more along this aspect of "we need our own space for conversation", it's unsustainable, having no space for conversation, so much so that the time I called him, it was 5 o'clock in the morning, I woke up and said, "can we talk?".

Other participants reported that the "birth of children" and the changes and conflicts that followed were the main reason for seeking help. In Rodrigo's and Patricia's case, for example, the children arrived after being married for a long time. Thus, the birth of children was both a reason for conflicts and the desire to invest in and maintain the relationship:

Researcher: Well, what was your initial demand? Why did you seek therapy?

Rodrigo: We sought it twice, right, once in 2000 and, I don't remember now, 2016 I think (…). Oh, we were, well, almost breaking up. So, like, let's try something instead of actually separating. We got married very early, right, and we were just the two of us for a long time, no children, by choice, you know? And then life without a child is one thing, right, and when the child was born was when, not the differences, but things get tougher.

Researcher: The family dynamics changes a lot, right?!

Rodrigo: We were, well, going through a very rough patch, fighting all the time and talking about separating. We even split up for a moment, like, I was away for a week, you know? And then I said "oh, let's go to therapy, before actually breaking up, you know?" And then the son weighed in a lot. The son for me was the two things: it was what changed the dynamics of our life, but he was also the reason for us to try to go on.

Another reason for the search for couple therapy was the "break of trust" that resulted from infidelity in marriage, and which Vanessa named as being a "betrayal". The discovery of sexual or affective relationships outside marriage generated a feeling of distrust, generating doubts about the possibility of keeping the marriage. However, as Vanessa tells it, other factors were affecting the couple when the infidelity happened, pointing out the need to review their motivations for marriage:

Researcher: And why did you seek therapy? What was your initial demand?

Vanessa: We've been together for 13 years, right, (…) and like, our last year was very difficult. We were working a lot, too much, him with the two companies there, me with the two here, and we ended up getting distant. Our routine started to get very heavy at home and in an accumulation of n factors, this crisis culminated in an infidelity. I traveled for a consulting job and that happened in the meantime. And, we were always very true to each other, we always talked a lot, and he told me.

"Distancing and disconnection" were the reasons that led Laura and Ricardo to seek couple therapy. They started to realize that they were living their lives more individually, not sharing plans and decisions. The distance created space for discussions and conflicts.

Researcher: Yeah, but was there any reason you two were not okay?

Ricardo: We weren't okay for a long time, but then it got to a point and we… when we started out and would come to [name of the city], we would travel a lot, we were always moving, and here we settled, you get what I mean? And then we started to pay attention to our relationship, you know? It wasn't good, but I can't explain it to you specifically, but it wasn't working out, things weren't fitting anymore, it wasn't pleasant. The day was over, and I didn't want to go home anymore, get it?

The emergence of "fights and disrespect" in the relationship also signaled the need to seek help. Maria and Pedro, for example, realized that they yelled and said things that hurt each other. Because of that, they began to question the possibility of staying married:

Researcher: And if I asked you, why did you two come to therapy? What was your initial demand?

Pedro: Hmm… it's just that we weren't putting up with each other anymore, Maria was yelling a lot, she was very upset, very irritated with everything and we weren't respecting each other, you know? So it wasn't cool.

Experiences during therapy

Many moments were significant for the couples during therapy, contributing to the joint construction of new understandings and to the transformation of the problems experienced. For many, therapy enabled the "exploration of relationship moments and qualities". Márcio and Vanessa, for example, recalled a dynamic proposed by the therapist in one of the sessions, in which he asked them to talk about good times they lived together. From the dialogue shared around the recalled moments, they recovered mutual values and thoughts, reasserting the reasons why they decided to be a couple.

Vanessa: After this dynamic, I had a meeting with some friends and (…) I had a click just like that, I said: My God, we are very cool together! I got to look at the relationship in a way that I couldn't look at it for months, you know?

The conversations in couple therapy also enabled the "exploration of individual stories". In the case of two participants, Julia and Maria, issues experienced in childhood and with the family of origin were present in the way they acted in the relationship with their spouses and children. For both, being able to understand that their attitudes towards their partner or children were related to personal experiences created more spaces for dialogue with them.

Researcher: And during this process, can you tell me about a significant moment that you experienced during therapy?

Julia: So, for me, what was very significant was that… they were asking things and we were answering, they led the conversation a little, right, and then at the end, at the end of a session, she said: "wouldn't all this that Julia is talking about be a fear of being alone, or a fear of the two of you distancing from each other?" And that made a big impression on me, because I had never thought about it, that all of this comes from fear, and then it reminded me a lot of my life story, my childhood, like this process of feeling abandoned, alone.

Participants also valued the therapists' action of "Giving a diagnosis" about the couple's situation or helping them build a better perception of the situations experienced. Maria, for example, had a perception that the therapist would say what was right or wrong in the situations that they would present as conflicting, or even say whether or not they should remain married, which did not happen. Rodrigo, in turn, said that it was important to receive a diagnosis from the therapist about the situation he and his wife were experiencing. The therapist's voice helped him to reflect about possible paths for the relationship.

Rodrigo: A moment I think was in the first (therapy), when she gave the diagnosis. (…) she said, "you are already separated, you need to decide now if you want to go back, because you already split up, after all that you're talking about, you're just living together, you are already split up, so you need to decide if you want to go back to being a couple, right, or separate and move, because in my opinion there is no couple here."

Therapy was also valued for "Showing the other side / offering new possibilities", allowing couples to see alternatives to an issue and realize that there may be different versions of events.

Ricardo: Look, for me, what stuck the most with me was the fact that I was able to make room in my head so that things could have a different view, you know? And then when you say that, I immediately think about (the therapist), his image came into my head just now, you know? (…) and it helped me a lot to see things in a different way, to put aside a certain point and see Laura's point, regardless of whether it's right or wrong, but, like, give a chance to another version of the story, see other possibilities (…).

For other participants, the therapy had the function of "providing a direction for the conversation / intermediating". Therapists made statements during the conversation that aided in mutual understanding. With that, therapy provided an "environment" different from other spaces, favoring dialogue and allowing the learning of ways of talking that, little by little, could be transposed into the home.

Márcio: I think the main gain there is that we would say things to each other during therapy with someone advising us. And it was very good, because he would say "so, let me see if I understood?" And he would talk to Vanessa and then ask me if I understood the same thing. And, then we would say "no, we understand the same thing". Often, in a discussion, the person says one thing and you understand another and then sometimes there was a fight or there was a misunderstanding. So, it was very good because there we had the opportunity to be guided towards a solution.

Addressing conflicts and problems was also valued by some participants, who understood that the therapy allowed for "washing dirty laundry". Marcos and Patricia mentioned that they would talk about many issues that bothered each other in therapy, bringing up aspects that they would like their partner to improve or do differently.

Marcos: I think we weren't even expecting it, but we learned to understand each other a little bit more, we have a lot of difficulty in discussing the relationship on a daily basis. I'm very introverted, and so is she, we end up avoiding it. So, the therapy was the time for us to bring up what bothers us in the other, the time to wash our dirty laundry, that was kind of the proposition and… That was exactly it and it was tense too, the 6-8 months, because we washed a lot of dirty laundry, there were times when I washed more than her, there were times when it was her, you know?!

"Listening to the partner vent" during therapy was also something valued by the participants. When listening, they perceived themselves to be more connected and sensitive to the feelings of the other, even though they were experiencing intense emotions or listening to things that were difficult to elaborate.

Marcos: This happened a few times, venting and saying what bothers us in the other. This happened more than once, I went there just to vent. Each of us has our own way of speaking (…) but then she would speak, and I would speak, so that sensitized us, made us understand each other's distress a little more, not necessarily agree, but at least respect each other's opinion. So, I think there were these matters of "wait, I don't agree with you", but at least I respect the way she interprets it or she values it or she sees it, you know? The component of understanding, of respecting, I think comes up a lot there, that was cool.

Changes after couple therapy

The experiences described were related to the changes achieved through the therapeutic process. We call it changes, as the gains are narrated as new meanings and, thus, new ways of life produced in the relationships based on couple therapy.

Some participants started "Prioritizing moments of dialogue between the couple". They recognized the need to take care of their conjugality, seeking to find times or create contexts so that conversations about the relationship could take place. When they felt strengthened as a couple, they were able to transfer the experiences of dialogue from therapy to their homes.

Vanessa: I believe that the paths paved there are powerful, right, for us to talk individually later and continue, so much so that this was something that happened after several sessions like. Sometimes not right after, but when we lay down at night, we still had some conversation there, which was an extension of what we had talked about that day and which was very important, because therapy ends up opening a path for conversation for you. After it ends, you leave, but that stays in your mind, so it echoes in other conversations that are valuable at home, more guided already.

One of the participants, Pedro, valued the possibility of "recovering individual space" through conversations in couple therapy. He realized that he stopped doing things he liked due to the relationship being in a rough spot, thus neglecting his own well-being.

Pedro: I like to get up, I like to watch movies and listen to music, music is my fuel, so I think I'm back to being me, I'm back to listening to music again, I'm back to doing those things I like that I wasn't doing anymore to avoid drawing attention. (…) I used to run, to compete in events, marathons, full-day races, and I suddenly stopped everything, now I'm getting back because we need to move our body, right, and the mind as well. And when the relationship isn't good, it seems that everything goes down the drain, right?

Couple therapy also enabled "reassessing what is important in the relationship". Participants began to realize which values mattered and made a difference in their lives, which moments they valued, what was good about the relationship and what they would like to recover.

Fabio: In the couple's daily routine, we leave so much on autopilot that we start letting go of that essence that united us, the love, the complicity, the companionship, you know? (…) Therapy helped us to always look for this, for what is our essence, right, our values. We like to go to mass together, we like to go out to eat, we like to share moments together, so we are always going to rescue that, right, not set it aside (…).

The possibility of "understanding the other" was also a change achieved. Participants reported developing empathy for the partner, respecting the values brought by the family of origin, understanding the other's moment and exercising tolerance towards the conflicts that arise in the relationship. Couple therapy allowed them to exercise the posture of putting themselves in the partner's place, starting to respect their values and beliefs. As a result, they realized that more frequent and open dialogue became part of the couple's relationship.

Researcher: Yeah, ok. And what can you see of change in the relationship that was brought about by the couple therapy process?

Pedro: Tolerance, right? Understanding, putting yourself in the person's shoes, for example, knowing how to listen more and trying to understand why the person asked you that, what caused that question, right? Or why the person is angry with you, what caused that irritation, you trying to understand the person's side.

Lastly, the therapy helped couples in "co-responsibility", that is, in developing a sense of shared responsibility for the paths followed. For them, the effect of the therapist's assertions and attitudes of inviting a relational look onto the issues described contributed to the reduction of a feeling of individual guilt.

Patrícia: I think that in the first time (therapy) there was a big change in rearranging the speech rights, both mine and his, right? Because I felt that in our conflicts back in the past, before our son was born, it was very he pointing his finger at me, blaming me a lot for the crisis, right?! And the first therapy was excellent to rebuild this, for us to understand the process in a more shared way, sharing the responsibility.

Discussion

The interviews carried out constituted rich spaces for dialogue. By recalling significant moments experienced in couple therapy, the participants, together with the researcher, produced new meanings about their relationships, reflecting on the motivations for the therapy and the changes achieved. In general, they were grateful for the opportunity for dialogue offered by the research, understanding it as another moment for them to reflect on their lives, which is compatible with Gergen's (2015) suggestion that the research, in a constructionist orientation, brings in its own event the possibility of transforming meanings and ways of life.

The interviews produced detailed reports on the therapeutic process, organized in a chronology that goes from seeking help to evaluating the gains achieved through couple therapy. The analysis carried out sought to give visibility to this procedural view and describe important dimensions of the therapeutic process according to the voices of the clients, which can be useful both for professionals and for the community. This is because the practice of couple therapy is still little known compared to other therapeutic modalities and is marked by stigma, sometimes reinforced by the media, which generally represents it as a stage for exacerbating conflicts. Reading about how other couples have experienced the therapeutic process can be helpful for people in the community to understand when to seek out this therapeutic resource, and what they can expect to achieve as a result of the conversations developed in this context.

The motivations reported by couples to seek therapy were diverse and are related to widely discussed points in academic literature, as they involve transitions in the family life cycle (Wagner et al., 2011). The birth of children, work overload and the adaptation to marital life itself - considering both the union of two people with different live experiences and the influence of their birth families in their lives - were discourses brought to support the narrative of emergence of conflict.

On this point, we believe it is important to reflect on the overload that seemed to cut across the lives of the men and women interviewed in our study. Among countless demands related to work and childcare, the relationship was relegated to the background. Finding time to talk, in the midst of so many responsibilities, was a challenge. On the one hand, they did not delegate the care of their children to others, as their bond with them seemed to be a relevant value in their lives. On the other hand, they saw themselves exhausted by modern society's logic of productivism, always demanding from them greater achievements and success in all spheres of life - including marriage.

To Vasconcellos (2002), the construction of a "we" does not depend solely on the sum of individualities, but on a process built and shared by the spouses, creating a third reality, which is the marital relationship. In this way, individuality and relationship are influenced by each other, that is, if the relationship is going through a difficult phase, it is likely that some individual areas can be negatively affected as well.

Madigan (2018), working with couples in conflict through a narrative perspective, sought to externalize the problem, inviting couples to reflect about aspects that contribute to marital conflict. Of particular importance is the author's reflection on the extent to which couples in conflict seem to be involved in caring for many other relationships (work, children, families of origin), neglecting their own. The author's question is: how many other relations does a relationship take care of? This is a useful reflection that often helps couples to realize that the conflict does not involve a difficulty that is internal to them, or a personal incompetence for the relationship, but is related to other demands for which they are also required on a daily basis and to broader social discourses that also guide expectations for relationships in a hegemonic way. In our research, hegemonic social discourses (such as patriarchal or gender discourse) permeate couples' narratives about the problem (Dickerson, 2013).

In a similar direction, Costa and Cenci (2014) reflect that the difficulty in finding moments of dialogue, the focus on professional life and the effort to balance life as a couple without losing individuality are factors causing attrition in relationships, causing the appearance of destructive feelings towards the partner and opening way to facilitate the breach of marital fidelity. Such meanings also appeared in the narratives of the couples taking part in the research, who suffered from the disconnection and, eventually, experienced situations of infidelity that undermined their trust in their relationship.

At the same time, for the couples, the crises that motivated the search for therapy also constituted possibilities to establish, with the help of their couple therapists, generative dialogues, which created openings to reflect on their demands and their ways of life, and, thus, jointly create new possibilities for the future. The participation of the couple therapist in creating of good conversational contexts was valued by all participants, who recalled significant moments in which conversational dynamics, questions or remarks were made in a way to broaden understanding of the situations experienced and reduce judgment or individual recrimination.

According to Shotter (2017), a dialogically structured interaction is a two-way street, in which people experience a responsive and caring relationship with each other, bringing to the conversation different modes of communication, such as gazes, body movements, facial expressions, rhythm and pauses in speech, in addition to verbal language. Adopting a dialogic-collaborative orientation, Anderson and Goolishian (2018) describe therapy as a conversation with dialogue, that is, the construction of a space for communication in which it is possible to jointly craft new narratives and stories.

Participants in our research evaluated that couple therapy provided "another environment", a different context, which favored dialogue and provided security so that difficult conversations could take place. Reflecting on the construction of good conversational contexts, Anderson (2017) talks about the importance of creating "hospitality", with attitudes on the part of the therapist that elicit listening and create a comfortable context for participation and mutual investigation. For the author, the therapist's ability to create a conversational space in which people can talk with each other (and not at or to each other) paves the way for the emergence of something "new", for the construction of new narratives and, therefore, for relationship change.

According to Grandesso (2011), the context provided by couple therapy is protected, it proposes rules for sincere conversations to occur. This way, conflicts are transformed into dialogue through the conversational arrangements proposed by the therapist. In a study by Bradford et al. (2016), the authors analyzed processes and outcomes achieved by couples who participated in a brief intervention. The couples they interviewed reported that therapists provide a safe environment so that they felt comfortable talking about feelings and difficult situations experienced in marriage. They also described therapy as an opportunity to listen to their partner's wishes, learn about things not said before, and identify areas of the relationship that could be improved.

In our research, we did not have access to the therapists' clinical management, due to our methodological design (interviews with couples, after therapy). However, the role of the therapist in the construction of this "environment" or context of dialogue proved to be important in the narrative of the couples interviewed, especially in terms of the ways in which the conversations were handled, an aspect also highlighted in other studies (Olson et al., 2012; Rober & Borcsa, 2016).

Through these narratives, we noticed the influence of constructionist assumptions and the values that permeate this theoretical orientation. The therapists' actions seemed to be informed: through investigation/explanation of the social construction, to the detriment of more essentialist orientations, that is, they sought to investigate the relationship stories that supported certain understandings; through the exploration of polysemy and polyphony, through the valorization and legitimization of different senses and voices; by seeking co-responsibility, to the detriment of individual blame (Gergen & Ness, 2016; Gosnell et al., 2017). However, we did not observe the valorization, in the participants' narratives, of the therapist's actions of problematizing how social discourses support the problem narratives, in a more political orientation, or even a view of the couple as inserted in other contexts - aspects commonly present in social constructionist proposals, especially in narrative proposals (Dickerson, 2013; Madigan, 2018). As we are not evaluating the professional practice, we cannot say that such emphases were not present in the clinic, only that they were not mentioned by clients.

The couples narrated many benefits or changes achieved through the therapeutic process. Among these, we highlight the learning of dialogue. Several couples reported that they were able to transpose the forms of dialogue that they had developed in therapy into the home. In this sense, the quote we chose for the title of this study is exemplary: "So, let me see if I understood".

As such, the way the therapists acted, which involved checking understandings and valuing different perspectives, began to guide the ways in which the couples started to talk outside of therapy. This type of learning was also observed by Grandesso (2011). In her research, she concluded that what couples take with them at the end of therapy is precisely the learning that meaning is a relational achievement. In this sense, "therapy" will always be an unfinished project. Life always presents new challenges to be overcome together through dialogue.

We agree with Blow et al. (2009) that couples who are committed to the therapeutic process and are willing to resolve the difficulties in the relationship bring an important component to the therapeutic process, which is the hope and motivation to keep striving to improve the relationship. Our research allowed us to meet valuable couples, committed to reflecting on their stories and concerned with thinking about how their actions affected their partners' lives.

Final considerations

The motivations that led our research participants to seek couple therapy were diverse, commonly associated with challenging moments of the life cycle and also with typical contemporary social pressures, especially related to work overload and raising children. Faced with so many demands and external pressures, couples had difficulties in taking care of their own relationship, starting to experience other challenges, such as fights, disconnection, disrespect and infidelity. The therapy offered couples opportunities to reflect, to better understand their points of view, to qualify their listening skills, to talk about individual issues, to vent and to develop a sense of shared responsibility for the challenges experienced, reducing practices of mutual blame. The therapists' action was described as significant, offering a model of conversation to be transposed to other contexts. As a result of the therapeutic process, dialogue was re-established in daily life, both concretely (through the creation of moments of conversation, a spot in the "schedule") and in the broader sense, of dialogical communication, as discussed in our analysis.

This article offers important resources for professional practice, making it clearer for couple therapists how clients ascribe meaning to their experiences in the clinical context and social discourses present in their reports. As a relevant point, the influence of the therapist in conducting the dialogue is explicit - which reinforces the importance of reflecting on how their actions take part in the construction of meaning. In addition to the scientific contributions to the literature on therapeutic processes, this research contributes to the dissemination of knowledge about couple therapy, considering that this practice is still not very well known or affordable. On this point, we stress that all but one of the couples participating in our study were heterosexual and had high income, the exception being a couple who attended the social clinic of a training institute.

Finally, we reiterate that this study approaches couple therapy from a social constructionist orientation. Although some points may be common to other therapeutic modalities and theoretical models, we make specific analyses based on this orientation. Conducting studies from other perspectives can contribute to the discussion of similarities and differences between clinical models. Likewise, research conducted on real practice scenarios and with an assessment of the therapeutic process as it happens may contribute to further discussions on the forms of clinical management of couple therapists.

References

Anderson, H. (2017). A postura filosófica: O coração e a alma da prática colaborativa. In: M. Grandesso (Org.), Práticas colaborativas e dialógicas em distintos contextos e populações: Um diálogo entre teoria e práticas, p. 21-34. Curitiba: CRV. [ Links ]

Anderson, H.; Goolishian, H. (2018). Sistemas humanos como sistemas linguísticos: Implicações para a terapia clínica e a terapia familiar. In: M. A. Grandesso (Org.), Colaboração e diálogo: Aportes teóricos e possibilidades práticas, p. 23-58. Curitiba: CRV. [ Links ]

Barbosa, M. B.; Guanaes-Lorenzi, C. (2015). Sentidos construídos por familiares acerca de seu processo terapêutico em terapia familiar. Psicologia Clínica, 27(2), 15-38. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-56652015000200002 [ Links ]

Blow, A. J.; Morrison, N. C.; Tamaren, K.; Wright, K.; Schaafsma, M.; Nadaud, A. (2009). Change process in couple therapy: An intensive case analysis of one couple using a common factors lens. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 35(3), 350-368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00122.x [ Links ]

Bradford, K.; Mock, D. J.; Stewart, J. W. (2016). It takes two? An exploration of processes and outcomes in a two-session couple intervention. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 42(3), 423-437. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12144 [ Links ]

Braun, V.; Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Braun, V.; Clarke, V. (2020). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360 [ Links ]

Costa, C. B.; Cenci, C. M. B. (2014). A relação conjugal diante da infidelidade: A perspectiva do homem infiel. Pensando Famílias, 18(1), 19-34. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1679-494X2014000100003 [ Links ]

Costa, L. F. (2010). A perspectiva sistêmica para a clínica da família. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 26(especial), 95-104. https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/revistaptp/article/view/17508 [ Links ]

Davis, S. D.; Lebow, J. L.; Sprenkle, D. H. (2012). Common factors of change in couple therapy. Behavior Therapy, 43(1), 36-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.009 [ Links ]

Dickerson, V. (2013). Patriarchy, power, and privilege: Narrative/poststructural view of work with couples. Family Process, 52(1), 102-114. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12018 [ Links ]

Diniz Neto, O.; Féres-Carneiro, T. (2005). Eficácia psicoterapêutica: Terapia de família e o efeito 'Dodô'. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 10(3), 355-361. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2005000300003 [ Links ]

Féres-Carneiro, T. (1994). Diferentes abordagens em terapia de casal: Uma articulação possível?. Temas em Psicologia, 2(2), 53-63. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-389X1994000200006 [ Links ]

Gergen, K. J. (2009). Relational being: Beyond self and community. Oxford: O.U.P. [ Links ]

Gergen, K. J. (2015). From mirroring to world-making: Research as future forming. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 45(3), 287-310. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12075 [ Links ]

Gergen, K. J.; Ness, O. (2016). Therapeutic practice as social construction. In: M. O'Reilly; J. N. Lester (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of adult mental health, p. 502-519. Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan. [ Links ]

Gosnell, F.; McKergow, M.; Moore, B.; Mudry, T.; Tomm, K. (2017). A Gavelston declaration. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 36(3), 20-26. https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.2017.36.3.20 [ Links ]

Grandesso, M. A. (2006). Diálogos contidos e monólogos compartilhados: Encontros e desencontros na construção de sentido nas relações amorosas. In: S. F. Colombo (Ed.), Gritos e sussurros, vol. 2, p. 33-50. São Paulo: Vetor. [ Links ]

Grandesso, M. A. (2011). Sobre a reconstrução do significado: Uma análise epistemológica e hermenêutica da prática clínica (3ª ed.). São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Hoffman, L. (1985). Beyond power and control: Toward a 'second order' family systems therapy. Family Systems Medicine, 3(4), 381-396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0089674 [ Links ]

Madigan, S. (2018). Entrevista relacional fundamentada na terapia narrativa: Preparando emocionalmente os relacionamentos conjugais conflituosos para uma possível reunião, separação, mediação e tribunais de família. In: M. Grandesso (Org.), Colaboração e diálogo: Aportes teóricos e possibilidades práticas, p. 201-224. Curitiba: CRV. [ Links ]

Martins, P. P. S.; McNamee, S.; Guanaes-Lorenzi, C. (2014). Family as a discursive achievement: A relational account. Marriage & Family Review, 50(7), 621-637. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2014.938290 [ Links ]

McNamee, S.; Gergen, K. J. (1995/2020). Introdução. In: S. McNamee; K. J. Gergen, A terapia como construção social (2ª ed.), p. 19-26. São Paulo: Instituto Noos. [ Links ]

Olson, M. E.; Laitila, A.; Rober, P.; Seikkula, J. (2012). The shift from monologue to dialogue in a couple therapy session: Dialogical investigation of change from the therapists' point of view. Family Process, 51(3), 420-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01406.x [ Links ]

Rober, P.; Borcsa, M. (2016). The couple therapy of Victoria and Alfonso. In: M. Borcsa; P. Rober (Eds.), Research perspectives in couple therapy: Discursive qualitative methods, p. 11-16. Switzerland: Springer International. [ Links ]

Satir, V. (1995). A mudança no casal. In: M. Andolfi; C. Angelo; C. Saccu (Eds.), O casal em crise, vol. 3, p. 29-37. São Paulo: Summus. [ Links ]

Shotter, J. (2017). Momentos de referência comum na comunicação dialógica: Uma base para colaboração clara em contextos únicos. Nova Perspectiva Sistêmica, 26(57), 9-20. https://www.revistanps.com.br/nps/article/view/274 [ Links ]

Shotter, J.; Katz, A. M. (1996). Articulating a practice from within the practice itself: Establishing formative dialogues by the use of a 'social poetics'. Concepts and Transformation, 1(2-3), 213-237. https://doi.org/10.1075/cat.1.2-3.07sho [ Links ]

Vasconcellos, M. J. E. (2002). Pensando o pensamento sistêmico como o novo paradigma da ciência: O cientista novo-paradigmático. In: Pensamento sistêmico: O novo paradigma da ciência, p. 147-184. Campinas: Papirus. [ Links ]

Vinuto, J. (2014). A amostragem em bola de neve na pesquisa qualitativa: Um debate em aberto. Temáticas, 22(44), 203-220. https://doi.org/10.20396/tematicas.v22i44.10977 [ Links ]

Wagner, A.; Tronco, C.; Armani, A. B. (2011). Os desafios da família contemporânea: revisitando conceitos. In: A. Wagner e colaboradores (Eds.), Desafios psicossociais da família contemporânea: Pesquisas e Reflexões, p. 19-35. Porto Alegre: ArtMed. [ Links ]

Recebido em 28 de outubro de 2021

Aceito para publicação em 14 de março de 2022

Este estudo teve financiamento da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) - código 001.