Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Journal of Human Growth and Development

versão impressa ISSN 0104-1282

Rev. bras. crescimento desenvolv. hum. vol.22 no.1 São Paulo 2012

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Maternal mental disease, parental styles and social support: study of the conceptions of the mothers and adolescents in the countryside of São Paulo state

Andrea Ruzzi-Pereira; Jair Lício Ferreira Santos

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Saúde na Comunidade, do departamento de Medicina Social, da FMRP-USP. Departamento de Medicina Social, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo. Av. dos Bandeirantes, 3900. Ribeirão Preto - SP

ABSTRACT

An observation of the women in the mental health service motivated the interest in researching as such mothers take care of their children and how these ones perceive this care. This study objectified to identify associations between parental practices of mental diseased mothers, social support and social-economical conditions; verify possible differences between parental practices of diseased mothers and healthy mothers. It is a quantitative, case-control study. Participated in this study 41 mental diseased women and their teenager children and 41 healthy mother-child dyads. It was observed a bigger dissatisfaction with the received social support to the sick mothers, that in these families the fathers are less responsive than the fathers of the compared group; mothers of the comparison group are more demanding and responsive than of the study group; the familiar economical situation also influences the maternal care. It is concluded that mood disorders, specially the depressive and anxiety disorder, the received social support and financial conditions influences the maternal care.

Key words: mental health; social support; maternal care; the depressive disorder, anxiety disorder.

INTRODUCTION

With the movement of the psychiatric reform the families saw themselves stimulated and pressured to once again assume the responsibility for the care of the sick members. Even today the familiar group faces the biggest responsibility of taking care of the people with mental disorders and become then, an important part of the social network of patient support1.

Under the focus of the ecological approach of the development, it is observed that a problem in any member of the family has effect in all the other members and changes in any member of the system can affect all the others2. So, the mental disorder of any member of the family will entail in some change in the life of all members of this famlies3.

Still focusing on the familiar system, it is observed that the care dispensed to the people with health problem specially devolves upon one unique family member, who compromises him or her self to give emotional, physical assistance, among others3. In our society, this person still is mainly the mother and when she needs special attention; her child can have his or her care impaired and the development affected.

Although there are lots of other forms of occurrence of mental illness in a woman, the present article limits itself to the mood disorder, specially the depression, and to the neurotic disorders, where coexist the depression and anxiety, for being of an epidemiologic relevance and relate the subjects of this study. While the mood disorder, mainly the depression are recognized as a problem of public health by the high incidence and prevalence in women all around the world and by its impact in the everyday life of the patients and the involved family members4-6, studies that investigate the influence of the maternal mental disease in the care dispensed to the children and the impact of this disease in the development of these children are still few in Brazil.

Depressed mothers perceive themselves as less capable or competent to effectively manage situations related to them as responsible for their children and their social support system is perceived by them as being less adequate, what increases the levels of depressive symptoms7. Such symptoms also can lead to serious economical consequences, being observed that the poverty and the lack of social support frequently occur together with mental disease. But the social support can moderate the effects of poverty and mental disease, promoting maternal actions of care more adequate and positives, even when the mother suffers from a serious mental disease, acting as a protection factor. Besides of contributing to the maternal psycho functioning, the social support decreases the financial and social stress, while more pronounced symptoms of depression point to a lower social support4, 8, 10.

It is considered social support a series of significant and appropriate protective factors, that the environment is able to provide, habilitating them to deal with environment stressors4. The existence of social support and absence of serious conflicts seen to be protector agents to the depression, while more pronounced symptoms of depression also points to a lower social support4, 6.

The literature has demonstrated that the mental disease interfere in the social relations, either by the fact of the disease enables or limits the person in his or her everyday activities or by the fact that people with mental disorders tend to socially isolate themselves. Epidemiological studies show that low social support, factors such as lack of the husband, social isolation, and a shortage of a confidante person associate to a bigger occurrence of depression4. In other words, the mental disorder can lead the person to isolation, and this in turn can lead the person to a depression.

On the other hand, studies has demonstrated that the social support facilitates the maternal involvement in education of their children, improves the maternal psycho functioning and decrease the social and financial stress8,9. Less stressed mothers are able to obtain a more effective social support and mothers with more social support involve themselves more in education of their children8,10.

The most appropriate way parents educate and relate to their children has been researched in the last decades. Studies propose a model of classification of parents in regard to the kind of behavior in relation to the control they that exert on their children and education they provide, called parental styles11. The study of the parental styles investigates the group parent behaviors that creates an emotional atmosphere in which it expresses the interactions parents-children, having as a base the influence of the parents in comportamental, emotional, and intellectual aspects of the children11,12.

The parental styles can be authoritative, authoritarian and permissive11-13. The authoritative parents are those who try to direct the activities of their children in a rational and oriented manner; they incentivize reasoning and educated objections; they exert a firm control in diverging points, putting their adult perspective, without restraining the child. The authoritarian parents model, control and evaluate the behavior of the children according to the rules of an established and absolute conduct; demand obedience and use punitive measurements to deal with the aspects of the child who ends in conflict of what they think to be correct. The permissive parents, who can adopt indulgent or negligent postures, try to behave in a non punitive manner and be receptive to the desires and actions of the children; they present themselves as a resource to the accomplishments of their desires and not as responsible agent for directing their behavior12.

The parental styles influence the children and adolescent development, differently one to another. These styles associated to the maternal mental illness can even have negative consequences. A North American study conducted by Petterson and Albers (2001) showed that maternal depression and poverty risk the development of their children. They also verified that depressed mothers present difficulties in the care their children and also that these difficulties reflect the symptoms of their illness. Compared to non depressed mothers, the maternal behavior of depressed women is generally characterized as less responsible, more hostile, less demanding and less active, and generally less competent14.

The presence of maternal depression is known to be one of the strongest risk factors to psychopathologies in their children. The maternal depression also can lead to social insecurity feelings in the children8-9. Children belonging to depressed women also present a more aggressive behavior than the children of non depressed mothers15-17.

The study of Petterson and Albers (2001) also analyzed another risk factor; a low source of family income, and obtained that the mothers with a low source of family income who were with depression symptoms perceived their own capacity of mother care as more difficult, they were less care providers to their children than mothers who experienced less psychological anxiety. The study suggested that the economical difficulties increase problems in the parental care and in consequence, an inefficient behavior of attention to education that affects negatively the adolescent14.

It is important to observe that the risk factors to the depression here cited form a causal network, in which, each factor does not affect only directly the individual but also interact with the other members of the family and social network. A negative parental style in the initial phases in the development increases the risks of problems in the development. Besides that, the mental disorders are by nature episodic and the children of parents with mental disorders, commonly experience more than one episode of the mental illness from the parents, influencing more than one phase of the development8,18.

This study has as its objectives identify associations between the parental practices of mothers with of mood disorder, the social support and socio-economical conditions; and verify possible differences between parental practices in mothers with mood disorder.

METHODS

The study was accomplished in a small city of Sao Paulo, that has an specialized treatment in Mental Health; and serves the cities of the Regional Department of Health(DRS-XIII19).

Two groups were studied; one of them was denominated study group and the other one was denominated compared group. The study group was composed by the users of mental health ambulatory services who had adolescents and one de their children and the compared group was composed by women of the same city, that never received diagnosis of mental disorder and/or another serious illness or disablements who had adolescents and one of their children. Eighty two mother-child diads participated in the research.

The study utilized for data collecting: (a) the Questionnaire of Social Support (SSQ ) 20, that is composed by 27 questions in which the respondent must indicate first, the number of sources of perceived social support (SSQ-N), the satisfaction with this support (SSQ-S), through a scale of 6 points that varies from very satisfied to very dissatisfied. The instrument also supplies data related to the source of social support (SSQ-F); (b) the Scales of Demanding and Parental Responsiveness, translated and adapted to Brazilian Portuguese21. The scales are composed of two instruments of 24 items (12 items to demand and 12 items to responsiveness, respectively), in which the adolescents evaluate attitudes and practices of their parents toward them, related to the referred dimensions, through the five-point Likert system indicating (separately to the father and mother) the intensity or frequency of the attitudes and behaviors described in the sentences; and (c) The Criterion of Brazilian Economic Classification (CCEB)22 has as its function, estimate the purchasing power of the people and urban families, abandoning the pretension of classifying the population in terms of " social classes". The system of scores is obtained with basis in responses related to the possession of some items at home and also considers information about the degree of instruction of the householder. All the instruments had already been validated to Brazil by the respective authors.

A pre-test was accomplished using a Questionnaire of Social Support, the Scales of Demand and Parental Responsiveness and the Criterion of Brazilian Economical Classification - CCEB to calibrate the questions of the instruments and check the comprehensibility of the items of the document, not being necessary to accomplish any kind of alteration in it. After the approval of the research by the Committee of Ethic in Research of the School Health Center School of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo (protocol 0189/CEP/CSE-FMRP-USP), an authorization of a search field to the city and health services was requested and conducted a survey of subjects that responded to the criterion of inclusion of research, from the medical records of the care of mental health service in the city. The survey sought for homogeneity of the sample in relation to the maternal diagnosis, time spent together of the adolescent with the mental illness and age of the child. 91 women who were in treatment for at least four years were selected24, in which the medical records had an indication that they had children with an average of 12 to 18 years old. Also were selected women whose medical records did not specify the absence of the children or age of them.

Thirty five of the selected women were excluded for not meeting the criterion of inclusion and five people refused to participate in the research.

The recruitment of the study group participants was done by telephone invitations, and then scheduling the date, time and place for applying the questionnaires used both by the mothers and their adolescent child. In the scheduled day, the informed and free consent term was read and after checking the comprehension and acceptance of the participants, the questionnaires and scales were given to them to be responded. There was no withholding of the consent in any case.

From the data collected from subjects of the study group, the schools where the adolescents of this group belong were then identified. A field authorization was requested to the principals of these schools for surveying the students demographic data, to localize families that could fit in the criteria of inclusion to the compared group, these criteria are: age of the students, years of study, gender and similar residential area to the study group; and at last that mother did not have a diagnosis of mental illness or disabling disease.

The private school did not agree to collaborate with the research, even being the adolescents chosen to build the compared group localized through indications of other teenagers of the target neighborhoods. All the families of the compared group accepted to participate in the research.

Each participant received information in regarding to the objectives of the study, being free their participation. When there is an agreement, the participants signed the informed consent.

The mothers of the two groups responded the Questionnaire of Social Support (SSQ) and the Criterion of Brazilian Economic Clasification( CCEB). The adolescents of both groups responded the Demand Scale and Parental Responsiveness. The questionnaires were self-evaluated and self-explanatory, which were applied in a single day interview. Each participant responded to questionnaire individually requesting the help of the researcher when necessary.

The data collecting took place within the months of April and July 2006, being accomplished by the researcher, who received orientation from the authors of the collecting instruments.

There was not any form of financing to this research. This study followed all of the Brazilian current norms of research with human beings, which is according to the Resolution 196/1996 CNS.

RESULTS

Sample Characterization

The group of study was composed by:

1. Forty one women, with ages ranging from 29 to 54 years old, of which 34,15% were up to 39 years old, 51,22% were ranging from 40 and 49 years old and 14,63% seemed to be 50 years old or more. These women were in treatment and presented psychiatric diagnosis for at least four years, identified in the categories "Mood Disorders", framed in the classification F30 to F39 from the Classification of Mental Disorder and Behavior of International Classification of Illness ( Classificação de Transtornos Mentais e de Comportamento da Classificação Internacional de Doenças )- CID-1023, of which 32 subjects with diagnosis between F31 to F33 from CID-10 e " Neurotic Disorder, related to stress and somatoforms", found nine women with the diagnoses F41.2 e F43.2. This number of participants represented all the women that were being treated in the period of June to July 2006 that responded to the criteria of inclusion to the research. All the women had at least one child with ages ranging from 12 to 18 years old.

In this group, 63, 41% of the women were married. There were 12,2% women who lived with a partner, 14,63% who were separated or divorced, 4,88% who were single and 4,88% widows.

2. Forty one adolescents, with ranging from 12 to 18 years old, of which 36,59% with ages ranging from 12 to 14 years old and 63,41% ranging from 15 to 18 years old, 53,66% male and 46,34% female, children of users of mental health service. The choosing criterion of the participant child was lower age and disposal to participate in the study.

The composition of the compared group was:

1. Forty one women, with ages ranging from 26 to 54 years, of which 26, 83% were up to 39 years old, 56, 10% were ranging from 40 and 49 years old and 17, 07% presented to be 50 years old or more; who never received psychiatric diagnosis and/or another serious or disabling illnesses, and that possessed older teenagers, with ages ranging from 12 to 18years old.

From this group 68, 29% of the women were married, 19, 51% lived together with a partner, 7, 32% were separated or divorced and 4, 88% were widows.

2. Forty one adolescents, with ages ranging from 12 to 18 years old, of which 39,02% with ages ranging from 12 to 14 years and 60,98% raging from 15 to 18 years old, 48,78% male and 51,22% female, children of women from the compared group , matched with the adolescents of the study group in relation to gender, age, and neighborhood.

In both groups, study and compared, 53,66% of the adolescents had completed their studies up to 8 years and 46,34% of the adolescents had completed 9 years of study. This number is identical due to the form of search of the compared group that happened taking in consideration the classroom of the adolescents of the study group.

The groups were classified according to the Criterion of Brazilian Economical Classification (CCEB), of wich 51,22% belonged to the study group and 53,66% of the compared group classified as Class C. One family (2, 44%) was classified as A2 in the study group and two (4, 88%)in the compared group. It was identified in the class B1 two (4, 88%) and five (12, 20%) families in the study and compared group respectively. It was indentified in the class B2 19, 51% of the families from the first group and 17, 07% of the families of the second, of which 21, 95% of the families belonged to the study group and 12, 20% of the compared group identified as Class D.

Statistical Analysis of the Results

In order to synthesize the results, the preference was given to the median as a measure of central tendency, since the dependent variables (scores of SSQ, SSN, Responsiveness and Demand) are all of from the ordinal kind. For the same reason the tests and measures are from the non parametric kind.

In order to verify the relevance of the eventual differences between the groups and /or among the categories of the variables, it was applied the Fisher Exact Test, the U Test of Mann - Whitney, The Kruskal Test - Wallis and the Significance Test of the Coefficient of Correlation of Spearman.

It was admitted as probability of error of first alpha specie < 5%.

The obtained results in relation to the number of perceived social support (SSQ-N) and the satisfaction of the women in relation to this social support (SSQ-S) showed that the medians of the number of perceived social support varied from 1.4 to 2.6, in both groups, even when compared to any social-demographic variables. The results showed that although the number of sources of social support found to be small, the mothers presented to be very satisfied with the quality of the perceived social support (SSQ-S).

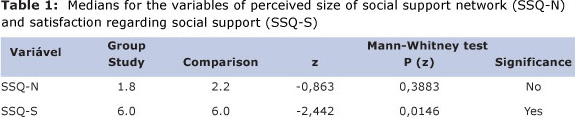

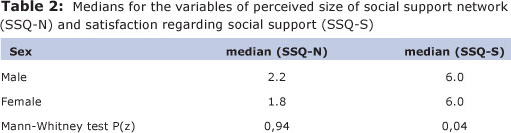

The results showed a higher satisfaction in relation to the perceived social support by mothers from the compared group than by the mothers from the study group (Test of Mann-Whitney, p = 0, 01). It was observed that mothers of boys refer a increased degree of satisfaction than the mothers of girls (p = 0, 04). (Table 1) and (table 2).

In what is related to styles of parental practices, the data obtained with the adolescents showed that, generally, sons and daughters consider their mothers more demanding than responsive, but when considered the groups of adolescents by gender, on average, the girls feel their mothers more responsive and demanding than the boys in both groups.

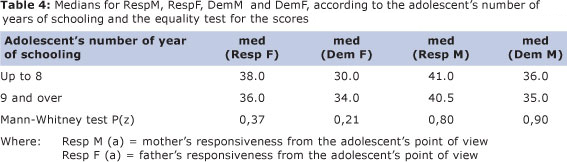

The burden of the maternal responsiveness perceived by the boys and girls was higher in the age group from 12 to 14 years of the adolescents with up to 8years of study than the group of adolescents ranging from ages 15to 18 years old with 9 years of study or more. On average, the compared group attributed a higher burden of maternal demand than the study group when compared to the variables age and years of study, but the adolescents of the study group with up to 8 years of educational level attributed a higher burden of demand to their mothers, when compared to adolescents of the compared group with the same amount of years studied.

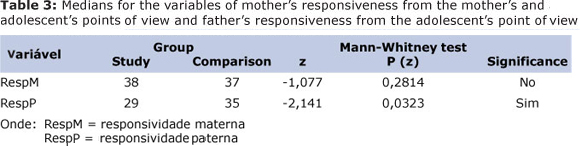

Generally, higher burdens of demand were attributed to mothers than responsiveness, but when compared to the burdens attributed to the fathers, the mothers were even more responsive (table 3). The study group, when compared the parental style by age, and years of study of the adolescents, attributed lower burden in both parental styles than the compared group. It was observed that girls at the age of 12 to 14 years old attributed a lower burden of responsiveness to parents than the boys at the same age. This was inverted in age group from 15 to 18 years, in both groups. (Table 4)

At the end, the averages of maternal and paternal responsiveness and demand were analyzed according to the purchasing power of the families and the gender of the children. As in the previous comparisons, the adolescents perceived their mothers and fathers more demanding than responsiveness and the averages of the burden of demand and responsiveness attributed to mothers were higher than those attributed to the fathers. The boys of the classes with a higher purchasing power considered their parents more responsive than the girls of these classes in both groups. The boys of the study group of these classes also considered their parents more demanding than the girls. The girls of the class C, in both groups, considered the parents more responsiveness than the boys, as well as the girls of the class D of the compared group.

DISCUSSION

The results obtained through the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ) evidenced that families whose mother has mood disorder were less satisfied with the degree of social support they receive than the families of the compared group. Similar results were obtained in another study25, which showed that depressed mothers perceive their social support less positively than their non depressed pairs. The maternal depression was related with a poor sense of competence in the parental practices and a inadequate perception of social support.

Also it was possible to observe an influence of gender in relation to the satisfaction with the perceived social support. The data showed that the mothers of girls were even more dissatisfied with the received social supported. This can be related to problems of behavior that manifest itself in a different way in boys and girls children of women with mental disorder. Also can be related to the fact that boys born from depressed women present more problems of externalization of behavior, girls on the contrary present as a response to the maternal illness behaviors of internalization6,11 what makes a great number of person, such as familiar members, teachers or health professionals, get involved to help in the solution of a such problem, the mother may perceive a great number of sources of social support, yet involved, as first reason, as a problem of the boy and not of the mother´s. However it wasn't found in the researched literature data about the difference in the social support perception to women with mental disorder, mother of boys or girls.

Another hypothesis surveyed would be the cultural factor. In our society, mothers expect their daughters be more companions and closer to them than the sons. If in one hand depressed mothers perceive themselves less satisfied with the social support they receive, on the other hand, the mothers of girls, in general, have a higher expectancy about the support and companionship that they should establish with their children. In this case, however, the girls keep a internalization behavior that makes them less supportive and allow them to give less help to their mothers in their social networks.

In what refers to the styles of parental practices, the results obtained with the adolescents showed that sons and daughters consider their mothers more demanding than responsiveness, but when considering the group of adolescents by gender, in average, the girls feel their mothers more responsive and more demanding than the boys, in both groups. Similar data were obtained in previous researches 11, 21. These researches suggest that the girl recognize more the parental influences than the boys, what ends by reflecting it in the results of the studies. These researches also suggest that these results can be a cultural reflex, where the girls are more protected by their parents and tend to be charged by the responsibilities sooner than the boys.

The results of this study also evidenced that the husbands of women with mental disorder are less responsiveness than the husbands of healthy husbands. The burden of responsibility attributed by the adolescents to their parents was significant in the comparison group (p=0, 03). This data went against another discoveries16, in which the authors found that in families where the mothers were depressed, the fathers provided higher levels of care to children than the fathers of families whose mothers weren't depressed. However, this study16 was done with parents of younger children. It is worth to remember that that the relationship between parents and children tend to be established in a different way in the adolescence. Thus, the parents of smaller children can supply the necessity of their children when the spouse has mental disorder, but fathers of adolescents can act differently with their children, who tend to present a behavior of confrontation, which makes the mothers even sick have more responsiveness than the fathers.

In relation to the women, this study found that the women of the compared group are more demanding and more responsiveness than the mothers of the study group and generally, the mothers are more responsiveness and more demanding with the younger children and thus, with less level of study. This study agrees with the other studies7,8,12,21, that points to an decreased maternal responsiveness and demands in families whose mother has mental disorder and, independent of the occurrence of mental disorder, the mothers are more responsive and demanding with younger children and, therefore, with less level of study.

The results also showed that the economical situation influences the maternal parenting practices, in which the mothers with less purchasing power present lower scores to responsiveness. These data agree with another studies9, 14, where the authors showed a correlation between the maternal mental disorder and poverty condition and miserability, suggesting that they frequently occur together.

In accordance with another studies made in the area, this study concludes that the inadequacy of the familiar environment26, the low social support and precarious financial conditions also influence in a negative way, but also concludes that appropriate social support can act as a protective factor, influencing positively in the maternal care.

We believe such conclusions alert health professionals of the necessity of intervention with families that has one or more family members with mental disorder in order to help in the formation of a social network support to sustain these families, decreasing the influence of the mental illness in the social relation of these people, enabling them to have a better life quality.

It is important to highlight that the discussions and studies related to maternal mental illness and the interaction of these mothers with their children are fundamental since an adequate intervention and prevention to the damage can contribute to the improvement of life quality of these families, as well as avoiding the adolescents also develop some mental disease and/or behavior disorder.

REFERENCES

1. Melman J. Família e doença mental: repensando a relação entre profissionais de saúde e familiares. São Paulo: Escrituras; 1998. p. 55-92 [ Links ]

2. Bronfenbrener U. A ecologia do desenvolvimento humano: experimentos naturais e planejados. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas; 1996. p. 161-182 [ Links ]

3. Matsukura TS, Marturano EM, Oishi J, Borasche, G. Estresse e suporte social em mães de crianças com necessidades especiais. Rev. bras. educ. espec. 2007; 13(3):415-428. [ Links ]

4. Lima MS. Epidemiologia e impacto social. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. [Internet]. 1999 maio [cited 2006 nov 27]; 21 Suppl 1:S1-5. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php [ Links ]

5. Andrade LHSG, Viana MC, Silveira CM. Epidemiologia dos transtornos psiquiátricos na mulher. Rev Psiquiat Clin. 2006;33(2):43-54. [ Links ]

6. Fleck MPA, Silva Lima AFBS, Schestasky SLG, Henriques A, Borges VR, Camey S et al. Associação entre sintomas depressivos e funcionamento social em cuidados primários à saúde. Rev Saúde Pública. 2002;36(4):431-8. [ Links ]

7. Silver EJ, Heneghan AM, Bauman LJ, Stein R. The relationship of depressive symptoms to parenting competence and social support in inner-city mothers of young children. Maternal Child Health J. 2006;10(1) 105-11. [ Links ]

8. Hammen C, Brennan PA, Shih JH. Family discord and stress predictors of depression and other disorders in adolescent children of depressed and non-depressed women. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):994:1002. [ Links ]

9. Oyserman D, Mowbray CT, Meares PA, Firminger KBBA. Parenting among mothers with a serious mental illness. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000; 70(3): 296-315. [ Links ]

10. Oyserman D, Bybee D, Mowbray CT, Macfarlane P. Positive parenting among African American mothers with a serious mental illness. J Marriage Family. 2002;64(1):65-77. [ Links ]

11. Oliveira EA, Marin AH, Pires FB, Frizzo GB, Ravanello T, Rossato C. Estilos parentais autoritário e democrático recíproco intergeracionais, conflito conjugal e comportamentos de externalização e internalização. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2002;15(1):1-11. [ Links ]

12. Weber LND, Prado PM, Viezzer AP, Brandenburg OJ. Identificação de estilos parentais: o ponto de vista dos pais e dos filhos. Psicol Reflex Crit [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2007 fev 28];17(3):323-31. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo [ Links ]

13. Costa FT, Teixeira MAP, Gomes WB. Responsividade e exigência: duas escalas para avaliar estilos parentais. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2000;13(3):465-73. [ Links ]

14. Petterson MS, Albers AB. Effects of poverty and maternal depression on early child development. Child Dev. 2001;72(6):1794-813. [ Links ]

15. Halpern R, Figueiras ACM. Influências ambientais na saúde mental da criança. J Pediatr. 2004;80 Supl 2:S104-10. [ Links ]

16. Hops H, Biglan A, Sherman L, Arthur J, Friedman L, Osteen V. Home observations of family interactions of depressed women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(3):341-6. [ Links ]

17. Santos, PL, GRAMINHA, SSV. Estudo comparativo das características do ambiente familiar de crianças com alto e baixo rendimento acadêmico. Paidéia. 2005; 15(31):217-226 [ Links ]

18. Bowlby J. Cuidados maternos e saúde mental. São Paulo: Martins Fontes; 1995. p. 27-50 [ Links ]

19. Brasil. Ministério do Planejamento. Orçamento e gestão [Internet]. Brasília, DF; 2005. [cited 2007/07/15]. Available from: www.ibge.gov.br/cidadesat/default.php [ Links ]

20 Matsukura TS, Marturano EM, Oishi J. O questionário de suporte social (SSQ): estudos da adaptação para o português. Rev Lat-Am Enfermagem. 2002;10(5):675-81. [ Links ]

21. Teixeira MAP, Bardagi MP, Gomes WB. Refinamento de um instrumento para avaliar responsividade e exigência parental percebidas na adolescência. Rev Avaliação Psicol. 2004;3(1):1-12. [ Links ]

22. Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil [Internet]. [cited 2005 nov 24]. Available from: http://www.abep.org/codigosguias/ABEPCCEB.pdf. p.1-4. [ Links ]

23. Organização Mundial da Saúde. Classificação de Transtornos Mentais e de Comportamento da CID-10: Descrições Clínicas e Diretrizes Diagnósticas. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas; 1993.p.108-170. [ Links ]

24. Brennan PA, Hammen C, Katz AR, Le Brocque RM. Maternal depression, paternal psychopathology, and adolescent diagnostic outcomes. |J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002; 70(5): 1075-85. [ Links ]

25. Silver EJ, Heneghan AM, Bauman LJ, Stein REK. The relationship of depressive symptoms to parenting competence and social support in inner-city mothers of young children. Matern Child Health J. 2006; 10(1): 105-11. [ Links ]

26. Fuller GB, Rankin RE. Differences in levels of parental stress among mothers of learning disabled, emotionally impaired, and regular school children. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;78:583-92. [ Links ]

Corresponding author:

Corresponding author:

andrea@to.uftm.edu.br

Manuscript submitted Apr 26 2011

Accepted for publication Nov 10 2011.