Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Actualidades en psicología

versão On-line ISSN 0258-6444

Actual. psicol. vol.27 no.115 San José 2013

ARTICLES

High point narrative structure in mother-child conversations about the past and children's emergent literacy skills in Costa Rica

Alison Sparks1,I; Ana M. Carmiol2,II; Marcela Ríos3,II

IAmherst College, U.S.A.

IIUniversidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica

ABSTRACT

The relationship between narrative coherence in mother-child conversations about past events and children's concurrent emergent literacy was examined in a sample of 32 Spanish-speaking, middle-class, Costa Rican mothers and their preschoolers. Coherence, as expressed in the constituents of high point narrative structure, was measured in reminiscing conversations about everyday events. Our purposes were twofold: 1) to see whether their co-constructed narratives in talk about the past could be meaningfully examined for the constituents of high point narrative structure and 2) to explore the links between coherence in these narratives and children's language and literacy skills. We found a full range of the constituents of high point structure in these conversations, with more advanced forms of narrative structure produced in conversations about the child's misbehavior. Conversations about misbehavior events were most frequently in the form of classic, high point narratives. In addition, a rich set of relationships between coherence in reminiscing conversations and children's language and literacy skills were observed. The results revealed similarities in the narrative practices found in this middle-class sample in Costa Rica to both middle-class families in other parts of the world and to conversation and cultural practices unique to Latino communities.

Keywords: Parent-child conversations, reminiscing, autobiographical memory, narrative, culture, elaborations.

RESUMEN

Este estudio examina la relación entre el nivel de coherencia narrativa observado en conversaciones madrehijo sobre eventos pasados y el desarrollo de la alfabetización emergente de niños y niñas en una muestra constituida por 32 díadas costarricenses, de clase media, que utilizan el español como su lengua materna. Se determinó el nivel de coherencia presente en estas conversaciones sobre eventos pasados para lograr dos propósitos: 1) identificar si los elementos que caracterizan las narraciones con estructura de punto álgido estaban o no presentes en dichas conversaciones, y 2) explorar la relación entre el nivel de coherencia en dichas narraciones co-construidas y el desarrollo del lenguaje y la alfabetización de los niños y las niñas de la muestra. Nuestros resultados señalan la presencia de un rango importante de elementos de la narración con estructura de punto álgido en las conversaciones analizadas, encontrándose las formas más avanzadas en las conversaciones sobre eventos pasados en las cuales el niño o la niña presentó un mal comportamiento. La mayor parte de las conversaciones sobre mal comportamiento presentaron la estructura narrativa de punto álgido. Además, se encontraron múltiples correlaciones entre los niveles de coherencia narrativa de las reminiscencias y el nivel de desarrollo del lenguaje y la alfabetización de los niños y las niñas. Como tal, los resultados apuntan tanto a similitudes entre las prácticas narrativas encontradas en la muestra participante y las prácticas de familias de clase media en otras latitudes, así como también particularidades en las prácticas narrativas de las comunidades Latinas.

Palabras clave: reminiscencia, desarrollo narrativo, coherencia, alfabetización emergente, Costa Rica, Latinos.

Introduction

As caregivers and children reminisce, they participate in a social context that enriches children's abilities across developmental domains. Parent-child discussions about meaningful past events have a significant impact on children's cognitive-linguistic development, including children's early literacy skills (Leyva, Sparks, & Reese, 2012; Reese, 1995; Sparks & Reese, 2013) and their socio-emotional understanding (Laible, 2004; Leyva, Berrocal, & Nolivos, 2013; Van Bergen & Salmon, 2010). Some of the earliest research focusing on family reminiscing between middle-class, European-American mothers and children examined the emergence of highpoint narrative structure (Peterson & McCabe, 1983) in the development of children's narrative skill. During conversations with parents about significant past events, children between the ages of 3-6 from these families learn to tell high-point narratives, i.e., stories that introduce a complicating event that leads to a high point, and then provide a resolution. Moreover, ethnographic studies have documented the significance of learning to tell these kinds of stories for successful communication and learning at school (Heath, 1983; Michaels, 1981).

Findings from research on the ways Latino children are socialized to tell personal stories highlight the impact of the child's home culture on their narrative development, suggesting that their stories are structured differently from those told by children from mainstream, middleclass families (Carmiol & Sparks, in press; Melzi, 2000). Very little research has focused on the role of high-point narrative structure in reminiscing conversations and associated outcomes for children from Latino families. Nevertheless, some studies indicate that Latino children's personal narratives display elements of highpoint narrative structure (Wishard, 2008; Uccelli, 2008), which is typically associated with school discourse in children from non-mainstream backgrounds. In the work presented here, we will explore family reminiscing conversations in middle-class Costa Rican mother-child dyads to see whether 1) the constituents of high-point narrative structure emerge in their discussions about past events and 2) to explore the links between narrative coherence (as expressed in the constituents of high-point narrative structure within dyadic reminiscing conversations) and children's emergent literacy skills.

High Point Structure in Personal Narratives

A personal narrative is a recount of past events experienced by the narrator or by someone the narrator knows (Labov, 1972, Peterson & McCabe, 1983). In Labov and Waletsky's narrative framework, the minimal requirements for a narrative are two events that are linked by a temporal marker; though, a true narrative is not only a string of events, but it must also contain orientations such as the who, what, where, and when of the story, as well as evaluative information that reveals the narrator's perspective on the story plot. Labov (1972) proposed a prototypical scheme for narrative structure that all stories draw upon and can be used to understand any oral account of lived personal experience: personal narratives are organized to contain orienting information, a complicating event, which leads to a high point, and then some kind of resolution, and a coda. The coda wraps the story up, with a sense of a lesson learned, but is not as essential as the other constituents of high-point structure. Labov and Waletsky noticed that not all narratives contain the complete structure, but are constructed from pieces of the model.

Drawing upon the Labovian scheme for narrative structure, Peterson and McCabe (1983) observed the emergence of storytelling in parent-child discourse over time. Their focus was on the socialization of children's narrative skills: How do children learn to recount meaningful past events? They looked to reminiscing as a conversation context that was ripe for observing how children learned to become skilled personal storytellers and how parents contributed to that process. As they examined conversations between mothers and children in samples of middle-class, European-American children, the stories revealed a clear developmental progression in which a mature narrative, one that orients the listener to the who, what, where, and when of the event, builds to a high point and then resolves in some way, was mastered by middle-class children at about 6 years of age.

Moreover, Peterson and McCabe (1983) found that before children developed the skills for telling a classic narrative, they told stories that were simpler in form and included some features of high-point structure, but not all. On the way to telling classic, high point narratives, three patterns of narrative were observed: leapfrog, chronological, and ending-at-highpoint narratives. All together, these four styles accounted for the personal stories told by the children in their sample, whose ages ranged from 3-and-a half to 9-and-a half years of age.

Peterson and McCabe (1983) classifi ed some of the earliest stories children told as leapfrog narratives because the narrator jumps from event to event with no sense of what may be an essential story element or sequence of the events. This kind of narrative was typically observed in children at very early stages of narration and usually disappeared by four-and-a-half-years of age. Chronological narratives are stories that consist of a proper sequence of events, but with no high point or perspective included; these stories have no evaluative markers and serve only to recapitulate a series of events (e.g., a story about a vacation trip). Chronological narratives were typical of four-year-old children, but were observed at all ages. The narrator reports events that are chronologically sequenced and build to a high point. Ending-at-high-point narratives include all of the components of a classic narrative, only the resolution is missing. McCabe and Peterson found this to be most frequently observed in 5-year-old children. One aim of this study is to see whether high-point narrative structure typically observed in stories told by children from middle-class, European-American families can be found in the narratives produced in reminiscing conversations in Costa Rican families from middle-class backgrounds.

Links Between High Point Narrative and School Experience

High point narrative is a canonical form of storytelling for middle-class children from European-American backgrounds. Narrative development within this cultural group tends to nurture the ability to tell independent stories that are tightly organized and centered on a single and clearly identifi able topic (Melzi, 2000; Michaels & Cook-Gumperz, 1979). A pervasive finding in studies of reminiscing in middle-class families is that the narrative contributions of adults are aimed at stimulating the child's ability to tell highpoint stories that focus on and extend a single event. The use of high-point narrative structure is believed to facilitate communication and success from the earliest school experiences in which children acquire the language and literacy they will need to succeed in later academic work. This style has important implications for school success, where topic-centered narratives are the preferred discourse genre, and knowledge and acquaintance with this privileged style facilitates communication and learning (Feagans & Ferran, 1982; Heath, 1983; Michaels, 1981).

Reminiscing and Emergent Literacy

Emergent literacy, the skills, knowledge, and attitudes that are developmental precursors to reading and writing (Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998), is initially acquired at home in social interactions between caregivers and children. Reminiscing is an everyday home activity practiced in cultures throughout the world in which parents scoffold their children's ability to narrate personal stories (Miller, Potts, Fung, Hoogstra, & Mintz, 1990). Reminiscing provides a conversation context for children to learn decontextualized language skills, the ability to represent and convey experience purely through linguistic means without resort to surrounding context to support the narration. Snow (1983) suggested that as children learn to use language to construct the world without the support of the present environment, they develop knowledge that will help them to understand the world of print.

Several studies have demonstrated strong links between parent-child participation in elaborative conversations about past events and children's language and literacy skills, specifically between mother's elaborative comments and questions while reminiscing with their preschoolers and children's emerging vocabulary, story comprehension, narrative quality, and early literacy skills. These relationships have been observed longitudinally in a middle-class sample of families in the U.S. (Reese, 1995) and concurrently (Sparks & Reese, 2013) and longitudinally (Leyva, Sparks, & Reese, 2012) in low-income and linguistically diverse families in a U.S. sample as well. In Reese's (1995) longitudinal study of European-American mothers and their children (3-5 years of age), mother-child reminiscing over the preschool years was a more powerful predictor of children's language and literacy skills at 70 months than talk during book reading. In a study that examined relationships between reminiscing conversations in linguistically and ethnically diverse families from low-income backgrounds, Sparks and Reese (2013) found that mothers' elaborative questions and comments while reminiscing about behavior-related events were uniquely related to children's concurrent story comprehension and print concepts. In a longitudinal study from the same diverse sample of families, mother's elaborations while reminiscing, but not during book-reading practices, predicted preschoolers' phonological awareness skills at the end of preschool, even after controlling for beginningof- preschool phonological and vocabulary skills, and demographic variables (Leyva, Sparks, & Reese, 2012). The present study is the fi rst to examine the relationship between mother-child reminiscing and children's language and literacy skills in middle-class, Spanish-speaking families from Costa Rica.

Prior studies linking reminiscing and early literacy learning, suggest that mother's elaborations are a significant force behind children's emerging language and print-based skills. Mother's elaborations are also closely related to developing high-point narrative structure. Elaborative questions (interrogatives that anticipate the who, what, where, and when of the story) and comments (that add information to extend the child's contributions) can be viewed as the mechanism for learning to include the narrative components of high-point structure. Thus, mothers support children in the construction of high-point narratives through the use of elaborative questions and comments.

Cultural Differences in Reminiscing and Narrative Structure

Variations in conversation practices provide a window into cultural values surrounding children's socialization (Heath, 2006). High-point narrative may be a preferred form of story-telling in middle-class, mainstream cultures; however, it is well established that caregivers from different cultural backgrounds engage children in talk about the past in different ways (Scheiffelin & Eisenberg, 1984), refl ecting cultural differences in parental values for child rearing and broader socialization goals for their children (Melzi, 2000; Wang 2004). Daily engagement in routines, like reminiscing, provides a pathway for learning expected behavioral norms (Zucker & Howes, 2009). Narrative practices such as reminiscing, constitute an arena in which children learn and practice the necessary linguistic skills for narrative development; at the same time, reminiscing is a context in which children acquire the necessary cultural knowledge to become competent members of their community (Carmiol & Sparks, in press).

In a study that compared Anglo and Peruvian working-class mothers in talk about the past with their 4-year-old children, Melzi (2000) found that Peruvian mothers asked questions that were focused on increasing children's participation in conversation, while their Anglo counterparts asked questions that were focused on helping children to tell stories that were topic centered and included the many features that are markers of canonical narrative structure. These mothers helped children to focus on a single past event and to shape a story into a sequentially ordered and tightly constructed narrative.

Silva and McCabe (1996) observed that the sequence of events was often less prominent in personal stories told by Spanish-speaking children in the United States. They noted that Latino narratives are often about family members and relationships within the family and that these recounts were more concerned with the details of a story than providing a sequential account of events. Silva and McCabe concluded that Latinos told stories with a preference for description and evaluation over linear structure.

In another study of personal narratives produced by children, Rodino, Gimbert, Pérez and McCabe (1991) found that the personal stories told by Latino children did not focus on a chronologically organized description of the actions involved in the event. This study compared personal narratives told by 6- and 7-year-old African-American, Anglo-American and Latino children and the results showed that Latino narratives included fewer temporally linked clauses describing the actions involved in the event than the African-American and the Anglo narratives. Instead, Latino narratives included descriptions of single actions, not sequences of actions, and those descriptions were preceded and followed by contextualizing utterances and evaluations.

Uccelli (2008) compared the personal narratives of Spanish-speaking Andean preschoolers and fi rst graders and their Englishspeaking Anglo-American counterparts and found further evidence for a lack of emphasis on the temporal and sequential aspect of Latino narratives, though she found that Andean schoolage children told narratives that contained highpoint structure as well. In fact, both groups were able to construct sequential narratives, organized according to the logical succession of events and both groups also told non-sequential narratives, where the line of the story departed from a linear succession of events. Uccelli found two patterns in the non-sequential narratives in both groups: in partial departures, children used reported speech and short abstracts that did not disrupt the logical succession of events in drastic ways; and they used non-sequential narratives, called full departures, where the logical sequence was drastically violated through the introduction of fl ashbacks and foreshadowing. Interestingly, this latter kind of non-sequential narrative was more common among the older children from the Andean sample. Her study suggests that after a few years in school, children display a repertoire of narrative skills, some the product of home culture and others that incorporate canonical forms of storytelling that may be learned at home or at school.

In a study that broadened the scope of conversational topics during past event talk, Sparks (2008) found that when Latino parents from low-income families reminisced with their preschool-age children in four contexts (a shared and unshared event; and a misbehavior and a good behavior event), talk about past misbehavior had the strongest associations with their children's independent personal stories told to an unfamiliar researcher. In initiating talk about past misbehavior, the mothers specifically oriented the event to time and place, modeling the importance of contextual information at the outset of the story and their children generalized these contextualizing markers to their independent storytelling. Sparks concluded that conversations about misbehavior may be a special context for Latino parent's expression of socialization goals for children. For Latino mothers, reminiscing about misbehavior may provide a context to instruct their child about appropriate behavior and proper demeanor in social relationships. Our study was designed to further examine whether reminiscing about behavior-related events, especially about misbehavior, is a significant context for children's development in middle-class Costa Rican families, particularly for children's language, narrative, and literacy learning. We wondered whether reminiscing about past misdeeds affords parents the opportunity to teach children expected behavioral norms.

All together, these studies support a cultural bias in which the sequential/temporal dimension is a less salient feature of narratives told by Latinos than in other cultural groups (Silva & McCabe, 1996). Much of this research suggests that children from Latino backgrounds learn some elements of high-point narrative in family conversation (particularly orientations and evaluations), though there appears to be less emphasis on the temporal organization of a story. Furthermore, talk about misbehavior may be a special context for learning to tell coherent stories that express family values for appropriate behavior and thus have a significant impact on Latino children's early language and literacy.

High Point Narrative Structure and Latino Family Reminiscing

Most of the studies on Latino children's narrative development reviewed here demonstrated unique cultural practices within family reminiscing conversations and children's narrative production. Only one study analyzed Latino family reminiscing conversations for the presence of high-point narrative structure. Wishard (2008) examined the co-construction of personal narratives in conversations between Mexican-American mothers and children (3-5 years of age) from low-income families for the inclusion of high-point structure. She placed an emphasis on reminiscing as a dyadic context for meaning-making, in which both parent and child play a role in constructing a story. She found a range of structures demonstrating that the children's narratives became increasingly coherent over time. The most common narrative form produced by 4-year-old children in her study was the chronological narrative (in which the story includes several events ordered with a linear sense of time, but no high point, evaluation, or conclusion are included) and to a lesser extent children produced leapfrog narratives and classic high-point narratives at this age. There have been no studies that explore high-point structure in reminiscing conversations in Spanish-speaking families from middle-class backgrounds. This study is meant to fi ll that gap.

In doing so, we use Wishard's dyadic coding scheme to examine reminiscing conversations between middle-class, Costa Rican mothers and their preschool-age children for the constituents of high point-narrative structure. One aim of this study is to see whether the narratives produced by middle-class, Costa Rican mothers and children could be meaningfully analyzed with the constituents of narrative originally set forth in the work of McCabe and Peterson. We expect to find similar links observed in prior research between mother's elaborative questions and comments, and children's language and literacy development. However, in this instance, we expect to find those relationships between the constituents of high-point structure and children's concurrent language and literacy skills. We made the following predictions:

H1. Following Wishard (2008), and Peterson and McCabe (1983), these four-year-old children will produce a range of narrative forms made of the constituents of high-point narrative structure.

H2. The predominant narrative form observed will be the chronological narrative (Wishard, 2008).

H3. Increasing coherence observed in narrative structure in conversation about past events will be positively related to children's language and literacy skills (similar to Leyva, Sparks, & Reese, 2012; Reese, 1995; Sparks & Reese, 2013).

H4. The strongest relationships between highpoint narrative structure and children's language and literacy will be observed in the context of talk about misbehavior (similar to Sparks, 2008).

Method

Design and Procedure

A female researcher met each dyad twice at their home or at the child's daycare center or preschool. Each meeting lasted an average of 40 minutes. In the fi rst session, mothers read and signed a consent form and completed a sociodemographic form. They also created a list of recently experienced events in their child's life. They were instructed to discuss 4 of these events with their child. In the second session, children completed a comprehensive assessment of language and literacy.

Participants

Thirty-two children (17 girls; 15 boys; mean age 4;4, range: 4;0-4;11) and their mothers participated in the study. They lived in urban neighborhoods and were from middle class homes. All mothers but one had completed college, (7%, incomplete college education). Most of the mothers in the sample (47%) had a licenciatura degree, with some mothers having bachelors (33%) and masters degrees (13%). All participants were native Spanish speakers. Ninety-three percent of the children were enrolled in some kind of preschool program at the time of the assessment.

Parent-child narratives

Mothers were asked to remember recent past events that were unique and salient in the child's life. A list was created that included: 1) a shared event (one that the parent and child had experienced); 2) an unshared event (one in which the child had recently participated without the parent); 3) a misbehavior event; and 4) a good behavior event. We expected these four events to represent a range of contexts for reminiscing that have been observed across class and culture in other studies (for further discussion, see Sparks & Reese, 2013). Mothers were told to interact with their child as they normally do while engaging in this kind of activity. Dyads were left alone in the room to complete this task and the conversations were audiotaped.

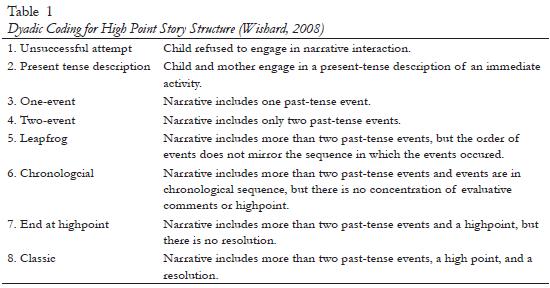

The reminiscing conversations were transcribed and coded for high point structure in each of the 4 contexts for talk for each dyad in the study. The narratives were coded for overall coherence using a coding scheme adapted by Wishard (2008) from Peterson and McCabe (1983) and based on Labov (1972). This coding system considers the participation of both the mother and child, with each narrative receiving a single code based on an 8-point scheme (See Table 1) that captured the variability of narrative structures produced by children in previous studies (see Table 3). Intercoder reliability was established with two Spanish-speaking independent judges on 25% of the transcripts. They obtained intraclass correlations of r = .77. Disagreements were resolved and the remaining narratives were coded by one of the judges.

Child language and literacy assessment. The Vocabulario sobre Dibujos Woodcock-Muñoz subtest (Woodcock & Muñoz, 1996) was used to assess receptive and express vocabulary skills for single words in Spanish. The Spanish version of Clay's Concepts about Print (Clay, 1979) was adapted to measure the child's conceptual knowledge about print. Questions 1-9 and 11 were used because those items did not require decoding skills (Sénéchal, LeFevre, Thomas, & Daley, 1998). Decoding of individual letters and single words were measured with the Identificación de Letras y Palabras subtest of the Woodcock-Muñoz battery (Woodcock & Muñoz, 1996).

Story retelling. As a measure of story comprehension (adapted from Reese, 1995), researchers read children an unfamiliar story, the Spanish edition of Peter's Chair (La Silla de Pedro, Keats, 1996) and then asked six comprehension questions. The questions were designed to measure recall of facts about the characters and setting, and the ability to make simple inferences about character motivation and story plot.

Narrative Quality. After the children answered the story comprehension questions, a puppet not previously visible was introduced. The child was then asked to retell the storybook to the puppet. The researcher assisted the children in retelling the story by turning the pages of the book and encouraging the child with generic questions or supportive comments (e.g., What's happening here? or "Tell me more."), but avoided elaborating on the child's retelling. The retelling was recorded and transcribed. The transcribed narratives were coded for memory units and narrative quality (adapted from Reese, 1995; Reese, Sparks, Suggate, 2012).

Initially, the text of the storybook was divided into 42 propositions. The text propositions were matched to units of information gleaned from the child's transcript of the retelling (which ranged from 1 to 40 propositions). One point was issued for each text proposition provided by the child. Each proposition was then coded for narrative quality, which included markers of evaluation, cohesion and literary language that were additional to those provided by the text. Children received one point for each example of narrative quality in each information unit. Coding of number of memory units and narrative quality, was completed by two independent judges for 25% of the story retelling task sample. Interrater agreements were calculated for memory units and narrative quality (Cohen's κ = .86 and .80 for memory units and narrative quality, respectively). Disagreements were resolved and the remaining narratives were coded by one of the judges. As a control for length of each story retelling on the overall narrative quality score, the total of the narrative quality points were divided by the number of propositions the child provided in order to create a narrative quality score for each participant. This score represents the average narrative quality score per proposition produced by the participant during the retelling. Only the narrative quality scores controlled for length were used in the analyses herein.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Asymmetry and kurtosis for all the variables were examined using protocols set out by Tabachnick and Fidell (2006). Children's scores in the decoding task presented a positive asymmetry. To reduce skewness decoding scores were then transformed using the square root.

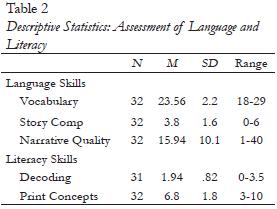

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics for the children's language and literacy measures and the high-point narrative structure for the entire sample. The mean standard score on vocabulary fell within the average for the normative sample, with a broad array of scores for individual children, some of them placing in the exceptionally high range. Children's scores on the measure of story comprehension produced quite a range, with most children able to name characters and recall story events, though answering the higher-order questions requiring predictions or inferences posed more of a challenge to this age group.

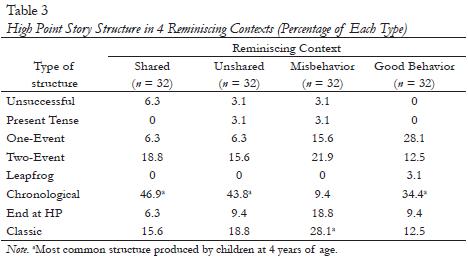

Table 3 presents the percentage of types of narrative structure found in the stories observed in the four contexts for reminiscing. The mothers and children produced the entire range of narrative structures, from presenttense description to classic narratives, within the four conversation contexts. Narrative structures within talk about good behavior, were a bit more constrained than talk in the other three contexts, with no unsuccessful attempts or present tense narrations observed. The most common narrative structure produced was the chronological narrative. In the shared, unshared, and misbehavior contexts, mothers and children told stories that recounted several events related to a single topic that contained some sense of sequence, but did not build to a high point with a resolution. In the misbehavior context, the classic narrative was the most common structure produced, as 28% of these narratives were in the form of a classic high-point narrative. With the addition of 18.8% of the stories classifi ed as end-at-high-point structure to the classic narratives, almost half of the stories told about misbehavior were constructed using narrative structures that are more typically observed in older children.

Correlational analyses

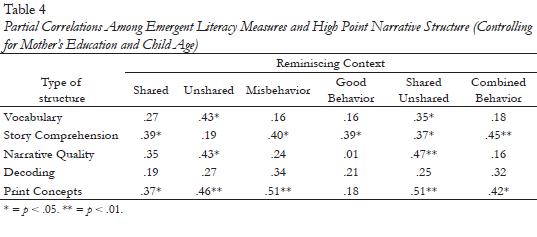

To further analyze the relationship between high-point narrative structure and children's language and literacy development, partial correlations between the high-point narrative structure coding for reminiscing conversations and child language and literacy measures were carried out (see Table 4), controlling for child age and mother's level of education (because these were correlated with several of the language and literacy measures). Given the close association between talk about shared and unshared events (r = .49, p < .01) and discussions of misbehavior and good behavior events (r = .56, p < .01), two additional variables were created: 1) combining shared and unshared events, which have been widely explored in samples of European-Amercian samples (for review see Fivush, Haden, & Reese, 2006); and 2) combining the misbehavior and good behavior contexts to represent talk about behavior-related events, which have been studied in other sociocultural contexts, from working-class children in Baltimore, United States (Miller et al., 1990) to middle-class families from Taiwan and China (Miller, Wiley, Fung, & Liang, 1997; Wang, 2001).

A rich set of relationships was observed between children's complex language and literacy skills, and narrative structure. Vocabulary stood out as the least related to narrative structure in the reminiscing conversations, with a moderate link to talk in the unshared context (r = .43, p < .05) and to a lesser extent in the combined shared and unshared context (r = .35, p < .05). Significant correlations were found between complex measures of child language in story comprehension and structure in the shared (r = .39, p <.05) and the combined variable, talk about shared/unshared events (r = .37, p < .05), and in all of the behavior-related contexts, including misbehavior, (r = .40, p < .05), good behavior (r = .39, p < .05), and combined behavior (r = .45, p < .01). Narrative quality was significantly related to talk in the unshared context (r = .43, p < .05) and in the combined variable, talk about shared and unshared events (r = .47, p < 01). Within yearprint- based skills, there were no significant relationships between children's decoding skills and high-point narrative structure. However, the strongest relationships were observed between children's conceptual knowledge about print and narrative structure in the shared (r = .37, p < .05); unshared (r = .46 , p < .01); misbehavior (r = .51, p < .01); in the combined shared and unshared context (r = .51, p < .01); and the combined behavior context (r = .42, p < .05). Overall, the strongest set of relationships was found in combined talk about shared and unshared events, where only decoding did not reach significance. Significant correlations were observed between high-point structure in narratives about shared and unshared events and vocabulary (r = .35, p = .05), story comprehension (r = .37, p < .05), narrative quality (r = .47, p < .01), and print concepts (r = .51, p < .01).

Discussion

The percentages for the types of narrative structure observed in the four reminiscing contexts confi rmed both our fi rst and second hypotheses. Similar to the work of Wishard (2008) and Peterson and McCabe (1983), these four-year-old children produced all of the constituent forms of high-point narrative structure, ranging from present-tense descriptions to the classic high-point narratives. This finding was somewhat surprising given that previous studies of reminiscing in Latino dyads have revealed significant differences in the structure and content of narrative of preschool-age children. During talk about good behavior, mothers and children produced a slightly more restricted range of structures, with no unsuccessful attempts or present-tense descriptions (scripted talk) observed. All of the mothers' bids to talk about good behavior events resulted in talk about specific memories of good deeds, suggesting that children find this topic of conversation highly engaging.

Our results reveal that high-point structure and its developmental precursors are embedded in past event conversations between middleclass mothers and children in Costa Rica. This is especially significant because these children are at the outset of preschool and so their stories do not yet refl ect the impact of formal schooling. The children observed here are learning to construct stories using high-point narrative structure in conversations with their mothers at home. Only Wishard's study (2008) examined high-point structure and included four-year-old Latinos from Spanish-English speaking bilingual families from low-income backgrounds. The mothers and children in Wishard's study produced a similar range of high-point narratives, as did middle-class, four-year-old children telling personal stories (Peterson & McCabe, 1983). Our findings also support Uccelli's view of a repertoire of learned narrative skills for Latino children, that include stories that focus more on evaluation and less on temporality in some cases, and in others, narratives that embrace high-point narrative structure.

As in Wishard's study of Latino dyads from low-income families in the South West of the U. S., the most common structure produced by four-year-olds while reminiscing about personal events, was the chronological narrative. Peterson and McCabe (1983) also found that chronological narratives were often told by four-year-old children (23%), though leapfrog narratives were the most commonly used structure (29%) at four years in their corpus of stories. Further research is needed to explore whether the chronological narrative is uniquely associated with four-year-old children from Spanish-speaking cultures or it is a universally preferred form of narration at four-years across cultural contexts.

It is particularly interesting that Costa Rican mothers and children attain such a high level of coherence in their past event conversations about misbehavior. The most common structure in stories told about misbehavior was the classic narrative, with 28% told in a classic structure that included a high-point and a resolution (See Appendix 2 for an example of a high point narrative in a mother-child conversation about misbehavior). This finding is all the more surprising given prior work in which classic narrative structure was not typically produced until 6-7 years (Peterson & McCabe, 1983; Wishard, 2008). The Costa Rican children in our sample appear to be quite precocious in their ability to formulate stories with high-point structure about events related to misbehavior. These advanced forms of story telling observed in conversations about transgressions add further support to previous work that singled out talk about children's behavior as a culturally salient topic of conversation for Latinos (Sparks, 2008). Research exploring parental attitudes and beliefs about child socialization has found that Latino parents (across social classes) place a high value on the importance of sustaining positive relationships with others and acceptance by the community (Harwood, Miller, Irizarry, 1995; Reese, Balzano, Gallimore, & Goldenberg, 1995). In our sample, these values are expressed in mother-child conversations about past misbehavior. While reminiscing, these Costa Rican mothers appear to impart values and beliefs about appropriate forms of behavior.

It seems important to acknowledge that family discussions about children's misconduct may provide the perfect content for expression in high-point structure. In other words, the core of high-point structure matches the content of a story about misbehavior, which always includes specific events that lead to a crisis that necessitate some kind of resolution. In this case, the content and structure of narrative are similar and probably mutually facilitative for children's narrative productions. Future research that focuses on reminiscing about misbehavior and behavior-related events is needed to see whether the prevalence of high-point narratives in talk about misbehavior is a unique expression of Latino family stories and cultural values, or if family discussion about misbehavior also facilitates high-point narrative structure at a relatively early age in other cultural groups.

Appendix 2 contains a sample of a motherchild conversation in the misbehavior context about a time that the child pinched a friend at school. As the two reminisce, the mother provides much of the orienting information and the evaluation and the child recounts many of the story events. At the high point, the child divulges that he not only pinched a friend, but he also broke the skin in doing so. The resolution, when the teacher asks him to leave the classroom and then allows him to return, is reported by the child as well. This story also includes a coda, in which the mother insists that the child recount a lesson learned - that it is better not to pinch your friend. This kind of dydadic coda has been observed in talk about past events in middleclass families from Taiwan (Miller, Wiley, Fung, & Liang, 1997) and is part of Labov's original narrative framework as well.

Our third hypothesis was borne out in the correlational analysis between the narrative structure coding and children's language and literacy measures. We found that increasing coherence observed in narrative structure in conversation about past events was positively related to children's language and literacy skills (similar to Leyva, Sparks, & Reese, 2012; Reese, 1995; Sparks & Reese, 2013), especially to children's complex language and their understanding of print concepts. Together, these findings suggest that engaging in talk about past events fasciliates specific kinds of linguistic skill, especially story comprehension and narrative quality. These skills draw upon receptive and expressive language abilities, challenging the child to understand lengthy dialogue across many turns and to formulate discourse so that the meaning of a story is conveyed clearly to the audience. In this way, reminiscing provides a bridge between children's early developing linguistic skills (like vocabulary) and their emerging complex language skills (story comprehension and narrative quality), that are crucial for learning to read.

Contrary to our final prediction, that the strongest relationships between high-point narrative structure and children's language and literacy would be observed in the context of talk about misbehavior, we found the most robust set of relationships between language and literacy in the combined shared and unshared context. More than any of the other conversational contexts, talk about shared and unshared events was associated with children's language and literacy. It was the only context in which all of the relationships to language were significant and the link to literacy, through print concepts, was the strongest correlation in the set. These associations provide further evidence for the many benefits of reminiscing about shared and unshared events for children's cognitive-linguistic development that have been demonstrated in studies of middle-class, European-American families (Fivush, Haden, & Reese, 2006). Middle-class children in Costa Rica, like their counterparts in other areas of the world, participate in this rich conversation format as they recount everyday events in talk with their mothers.

The moderate correlations between print concepts and high-point structure observed in the unshared, misbehavior, and in the two combined conversation contexts are noteworthy in that they replicate several studies that have found a link between mother-child reminiscing conversations and children's literacy related skills (Leyva, Sparks, & Reese, 2012; Reese, 1995; Sparks & Reese, 2013). Snow (1983) suggested that decontextualized language, the use of language to construct the world without the support of the on-going environment, is linked to the conceptual knowledge needed for early reading. She also observed that parentchild conversations about past events were a rich context for children to practice using decontextualized forms of language. Another explanation for this counterintuitive finding may be that parents' elaborative reminiscing promotes children's abstract thinking, which may then generalize beyond conversation to a variety of domains, including print skills (Leyva, Reese, & Wiser, 2011); or perhaps children who are more advanced in their abstract thinking, are able to capitalize on incidental learning to more readily acquire print skills (Sparks & Reese, 2013). It is also possible that future research will uncover other mediating factors in the relationship between reminiscing conversations and children's print knowledge that we have not included here.

The total lack of observed links between high-point narrative structure and decoding skills suggests that parents in this sample may not engage in teaching children to name letters, and that decoding is a skill that will be acquired soon enough at school, as these 4-year-olds are just embarking on their preschool experience. Parents in this study were not asked to report on teaching practices, so it was not possible to explore relationships between parent teaching and children's literacy skills. A longitudinal study is needed to explore the origins of Costa Rican children's decoding skills and to plot the integration of decoding with other literacy and narrative skills over time.

Finally, our study suggests that both talk about misbehavior and talk about shared and unshared events make an important contribution to middle-class children's developing language and literacy skills in Spanish-speaking, Costa Rican families. These children resemble their middle-class counterparts in other areas of the world in that they are learning to use high-point narrative structure in talk about everyday shared and unshared events as they reminisce with their mothers at home. Presumably, engaging in telling these kinds of stories, will bestow the same social and academic advantages that have been observed in samples of children from European-American families; though, more research is needed to examine the connections between remisnicing in Latino families and associated outcomes for children. At the same time, the advanced forms of story structure observed in reminiscing about misbehavior supports the view that talk about behavior, particularly misbehavior, appears to be an important context for communicating parental attitudes and values in Latino families. This too, deserves the attention of future research, to see whether talk about misbehavior fascilitates highpoint narratives in four-year-old children from other cultural backgrounds, or whether this is a narrative form that is a unique expression for Latino families and their preschool children.

Limitations

Given our small sample size, the analyses and interpretations herein are exploratory and deserve further attention in studies with a larger group of families. However, we visited homes to collect observational data, which affords a richer picture of parent-child interaction than questionaire data but is more difficult to collect. We are attempting to test our findings in other samples of children from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds and with larger sample sizes. We would also like to acknowledge that our study took a dyadic focus, which allowed us to place an emphasis on the co-constructed nature of narratives produced in parent-child past-event converations, but this approach did not allow us to isolate mothers' or children's independent contributions to the conversations or to children's developing language and literacy skills. Nevertheless, taking a dyadic approach to our data was consistent with a view of the developmental process as a spiral of mutual accommodation and infl uence (Fivush, et al., 2006), in which caregivers' and children's participation in conversation about past events embodies the process through which the child acquires essential cognitive and linguistic skills for learning to read.

The findings presented here were also constrained by a focus on concurrent measures of mother and child interactions and skills. In the future, we hope to conduct longitudinal studies that will further our understanding of the relationships among remininiscing, high point narrative structure and children's language and literacy outcomes in families from Latino backgrounds.

References

Carmiol, A.M., & Sparks, A. (In press). Narrative development across cultural contexts: Finding the pragmatic in parent-child reminiscing. In D. Matthews & N. Budwig (Eds.), TiLAR Series: Pragmatic Development. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Clay, M. (1979). Stones: Concepts about print. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Feagans, L.(1982). The development and importance of narratives for school adaptation. In L. Feagans and D. C. Farran (Eds.), The language of children reared in poverty: Implications for evaluation and intervention (pp.95-116). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Fivush, R., Haden, C. & Reese, E. (2006). Elaborating on elaboration. Child Development, 77, 1568-1588. [ Links ]

Harwood, R.L., Miller, J.G., & Irizarry, N.L. (1995). Culture and attachment: Perceptions of the child in context. New York: Guildford. [ Links ]

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Heath, S. B. (1986). What no bedtime story means. In B. Schieffelin & E. Ochs (Eds.), Language Socialization Across Cultures (pp. 97-125). NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Keats, E.J. (1996). La silla de Pedro (Trad, M. A. Fiol). Nueva York: Puffin Books. [ Links ]

Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner city. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [ Links ]

Laible, D. (2004). Mother-child discourse in two contexts: Links with child temperament, attachment security, and socioemotional competence. Developmental Psychology, 40, 979-992. [ Links ]

Leyva, D., Berrocal, M., & Nolivos, V. (in press). Spanish-Speaking Parent-Child Emotional Narratives and Children's Social Skills. Journal of Cognition and Development. [ Links ]

Leyva, D., Reese, E., & Wiser, M. (2011). Early understanding of the function of print: Parentchild interaction and preschoolers' notating skills, First Language, 1-23. [ Links ]

Leyva, D., Sparks, A., & Reese, E. (2012). The link between preschooler's phonological awareness and mother's book-reading and reminiscing practices in low-income families. Journal of Literacy Research, 44, 426-447. [ Links ]

Melzi, G. (2000). Cultural variations in the construction of personal narratives: Central American and European American mothers' elicitation styles. Discourse Processes, 30 (2), 153– 177.

Michaels, S. (1981). "Sharing time": Children's narrative styles and differential access to literacy. Language and Society, 10, 423-422. [ Links ]

Michaels, S., & Cook-Gumperz, J. (1979). A study of sharing time with fi rst-grade students: Discourse narratives in the classroom. Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Meetings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California. [ Links ]

Miller, J.M., Potts, R., Fung, H., Hoogstra, L. & Mintz, J. (1990). Narrative practices and the social construction of self in childhood. American Ethnologist, 17, 292-311. [ Links ]

Miller, P. J., Wiley, A. R., Fung, H., Liang, C. H. (1997). Personal storytelling as a medium of socialization in Chinese and American families. Child Development, 68, 3, 557-568. [ Links ]

Peterson, C., & McCabe, A. (1983). Developmental psycholinguistics: Three ways of looking at a child's narrative. New York: Plenum Press. [ Links ]

Reese, E. (1995). Predicting children's literacy from mother-child conversations. Cognitive Development, 10, 381-405. [ Links ]

Reese, E., Sparks, A., & Suggate, S. (2011). Assessment of narrative skills. In E. Hoff (Ed.) Blackwell Guide to Research Methods in Child Language (pp. 133-148). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell. [ Links ]

Rodino, A. M., Gimbert, C., Pérez, C., & McCabe, A. (1991). Getting your point across: Contrastive sequencing in low-income African-American and Latino children's personal narratives. Paper presented at the 16th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, Boston. [ Links ]

Scheiffelin, B. B., & Eisenberg, A. (1984). Cultural variation in children's conversations. In R.I. Schiefelbusch & J. Pickar (Eds.), Communicative competence: Acquisition and intervention (pp. 377-422). Baltimore: University Park Press. [ Links ]

Reese, L., Balzano, B., Gallimore, R., & Goldenberg, C. (1995). The concept of Education: Latino family values and American schooling. International Journal of Educational Research, 23, 57-81. [ Links ]

Sénéchal, M., LeFevre, J.-A., Thomas, E., & Daley, K. (1998). Differential effects of home literacy experiences on the development of oral and written language. Reading Research Quarterly, 32, 96–116.

Silva, M., & McCabe, A. (1996). Vignettes of the continuous and family ties: Some Latino American traditions. In A. McCabe (Ed.), Chameleon readers: Teaching children to appreciate all kinds of good stories (pp. 116-136). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Snow, C. (1983). Literacy and language: Relationships during the preschool years. Harvard Educational Review, 55, 165-189. [ Links ]

Sparks, A. (2008). Latino mothers and their preschool children talk about the past: Implications for language and literacy. In A. McCabe, A. L. Bailey, & G. Melzi (Eds.), Spanish language narration and literacy: Culture, cognition, and emotion (pp. 273-295). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sparks, A. & Reese, E. (2013). From reminiscing to reading: Home contributions to children's developing language and literacy in low-income families. First Language, 33, 89-110. [ Links ]

Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. (2006). Using multivariate statistics. Fifth Edition. New York: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Uccelli, P. (2008). Beyond chronicity: Evaluation and temporality in Spanish-speaking children's personal narratives. In A. McCabe, A. L. Bailey, & G. Melzi (Eds.), Spanish-language narration and literacy: Culture, cognition and emotion (pp. 175–212). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Van Bergen, P., & Salmon, K. (2010). The association between parent-child reminiscing and children's emotion knowledge. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 39, 51-56. [ Links ]

Wang, Q. (2001). "Did we have fun?": American and Chinese mother-child conversations about shared emotional experiences. Cognitive Development, 16, 693-715. [ Links ]

Wang, Q. (2004). The emergence of cultural selfconstructs: Autobiographical memory and selfdescription in European American and Chinese children. Developmental Psychology, 40 (1), 3-15. [ Links ]

Whitehurst, G. J. & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69, 848-872. [ Links ]

Wishard, A. (2008). The intersection of language and culture among Mexican-heritage children three to seven years old. In A. McCabe, A. L. Bailey, & G. Melzi (Eds.) Research on the development of Spanishlanguage narratives. (pp. 143-174) New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Woodcok, R., & Muñoz, A.F. (1996). Pruebas de habilidad cognitiva y pruebas de aprovechamiento revisadas. Itaka, NY: Riverside Publishing. [ Links ]

Zucker, E. & Howes, C. (2009). Respectful relationships: Socialization goals and pactices among Mexican mothers. Infant Mental Health Journal, 30, 501-522. [ Links ]

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

Postal address: Amherst College, Psychology Department, Box 2236, Amherst, Massachusetts, 01002, U.S.A.

Recibido: 15 de mayo de 2013

Aceptado: 21 de agosto de 2013

Acknowledgments: Portions of this paper were presented at the 2013 Biennal Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Seattle, United States. We would like to thank the participating families. Thanks to Javier Tapia, Mariano Rosabal and Renata Villers for their valuable comments and suggestions throughout the development of the study, and to Meliza Quirós for her help with data coding.

Funding: This research was supported by Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Universidad de Costa Rica.

1 Alison Sparks, Amherst College. E-mail: asparks@amherst.edu

2 Ana M. Carmiol, Universidad de Costa Rica. E-mail: ana.carmiol@ucr.ac.cr

3 Marcela Ríos, Universidad de Costa Rica. E-mail: marcela.rios@ucr.ac.cr