Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Temas em Psicologia

versão impressa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.27 no.1 Ribeirão Preto jan./mar. 2019

https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2019.1-12

ARTICLE

Retirement well-being: a systematic review of the literature

Bem-estar na aposentadoria: uma revisão sistemática da literatura

Bienestar en la jubilación: una revisión sistemática de la literatura

Silvia Miranda AmorimI; Lucia Helena de Freitas Pinho FrançaII

IOrcid.org/0000-0002-3066-0005. Universidade Salgado de Oliveira, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil

IIOrcid.org/0000-0001-6716-7217. Universidade Salgado de Oliveira, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil

ABSTRACT

The objective of this systematic literature review was to investigate the variables that would improve well-being in retirement by analyzing relevant empirical studies. In the literature search, six keywords (retirement, positive psychology, well-being, satisfaction, happiness and quality of life) were used in six international academic portals. This search identified 403 articles, and those meeting the pre-established inclusion criteria were extracted. The 55 articles selected were analyzed based on nine categories: language, year, journal, country, objective, dependent variable, instruments, independent variables and results. The studies had a longitudinal, transversal design or reported on instrument creation and validation. The literature review pointed out a large number of variables, confirming the multidimensionality of the constructs. Aspects highlighted include health, economic situation, gender, marital status, interpersonal relationships, whether retirement was voluntary, retirement duration and leisure activities. A compilation of variables and an agenda for future studies are proposed based on the results of this review.

Keywords: Retirement; well-being; systematic literature review

RESUMO

O objetivo desta revisão sistemática de literatura foi investigar as variáveis que provocariam bem-estar na aposentadoria, analisando estudos empíricos relacionados ao tema. Na busca, foram utilizadas seis palavras-chave (retirement, positive psychology, well-being, satisfaction, happiness e quality of life) em seis portais acadêmicos internacionais, emergindo 403 artigos, sendo extraídos os que atendiam aos critérios de inclusão pré-estabelecidos. Os 55 artigos selecionados foram analisados com base em nove categorias: idioma, ano, revista, país, objetivo, variável dependente, instrumentos, variáveis independentes e resultados. Os estudos tinham caráter longitudinal, transversal ou criação e validação de instrumentos. A revisão de literatura apontou um grande número de variáveis, confirmando a multidimensionalidade dos constructos. Os seguintes aspectos se destacaram: saúde, situação econômica, gênero, status conjugal, relacionamentos interpessoais, voluntariedade da aposentadoria, tempo de aposentadoria e atividades de lazer. Uma compilação de variáveis e uma agenda de estudos futuros foram propostas, baseando-se nos resultados desta revisão.

Palavras-chave: Aposentadoria; bem-estar; revisão sistemática de literatura

RESUMEN

El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática de la literatura fue investigar las variables que causan bienestar en la jubilación, analizando los estudios empíricos relacionados con el tema. En la búsqueda, se utilizaron seis palabras clave (jubilación, psicología positiva, bienestar, satisfacción y calidad de vida) en seis portales académicos internacionales, con 403 artículos emergentes, con los criterios de inclusión preestablecidos. Los 55 artículos seleccionados se analizaron en base a nueve categorías: idioma, año, revista, país, objetivo, variable dependiente, instrumentos, variables independientes y resultados. Los estudios fueron de carácter longitudinal, transversal o de creación y validación de instrumentos. La revisión bibliográfica señaló un gran número de variables, lo que confirma la multidimensionalidad de los constructos. Algunos aspectos fueron destacados: salud, situación económica, género, estado civil, relaciones interpersonales, voluntariado en la jubilación, tiempo de jubilación y actividades de ocio. Se propuso una compilación de variables y una agenda para estudios futuros sobre la base de los resultados de esta revisión.

Palabras clave: Jubilación; bienestar; revisión sistemática de la literatura

The trend of studying different phenomena by the positive look was inaugurated a little over a decade ago (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Since then, a number of studies have been developed to deviate from the focus on disease psychology and on harms, and special emphasis has been given to cognitive and emotional processes that allow promotion of each individual potentiality (Reppold, Gurgel, & Schiavon, 2015). During this period, study of positive psychology has contributed to construction of instruments that can be used to measure, identify, and enhance health of individuals and groups in their individual environments and institutions.

Among the main contributions of positive psychology is the development of theories and well-being. Among these is a study on the approach of subjective well-being (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffn, 1985). According to this approach, well-being includes global judgments and specific satisfaction with life and emotional experiences; this perspective considers theories on affect (positive or negative) and theories that support cognition and can be operationalized by satisfaction evaluations (Diener et al., 1985).

Positive concepts have overcome positive experiences in an individual perspective for social, cultural, community, collective and public policies. For example, studies have evaluated work engagement, positive aging, resiliency, and post-traumatic growth (Reppold et al., 2015). The same occurs with views of retirement; and the literature frequently used terminology that led to an optimistic vision of retirement consisting of well-being, satisfaction and resilience (Nalin & França, 2015).

The growth of the older population is a worldwide phenomenon. Although this situation is a positive one, it requires special attention regarding resources needed to assist this population. In Brazil, 1960 the life expectancy was 54 years; within only 57 years it increased by 22 years (i.e., in 2017 was 76 years; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], 2018). This rapid increase in the age of the elderly Brazilian population also agrees with the higher number of individuals who have retired without a guarantee of the sustainability of resources needed for well-being (França, 2012). There is a scarcity of studies and actions for retirees, and, because of the rapid growth in this age group, further studies on this topic are warranted, especially in Brazil (Boehs, Medina, Bardagi, Luna, & Silva, 2017).

Retirement can be seen as an advantageous or disadvantageous period for those who retire. On the other hand, the importance society places on work causes some to perceive retirement as a time of economic, emotional or psychosocial loss. On the other hand, cessation of work can be viewed as an opportunity to restart life, with additional freedom and more time for relationships and general activities (França, 2012).

Some researchers have demonstrated this more optimistic view of life during retirement - as a restart - but few scholarly studies have been done, especially in Brazilian (França, 2012). Previous reviews emphasized the scarcity of translated measures focusing on antecedents and consequences of this transition (Rafalski, Noone, O'Loughlin, & Andrade, 2017), behavioral measures (Barbosa, Monteiro, & Murta, 2016), and approaches to and diversity of methods of study and intervention (Boehs et al., 2017). In addition, the focus on positivity is still little approached in studies and education practices, orientation, or preparation for retirement (Siguaw, Sheng, & Simpson, 2016).

Despite existing gaps, there is consensus about the number of factors that determine the decision to retire and that can influence well-being (França, Bendassoli, Menezes, & Macedo, 2013). Among the most cited are financial and health conditions (Amorim, França, & Valentini, 2017; Hershey & Henkens, 2013; Van Solinge & Henkens, 2008), marital status, social and family relationships (Fouquereau, Fernández, & Mullet, 1999) and leisure activities (Earl, Gerrans, & Halim, 2015). In addition, longitudinal studies found positive effects of retirement, especially because of such circumstances such as voluntary retirement, advanced age and opportunity to engage in bridge employment, in which the individual continues to work but at a job with reduced time, with the aim to retire later (Dingemans & Henkens, 2015; França et al., 2013; Gall, Evans, & Howard, 1997; Latif, 2011).

Psychological perspectives related to retirement are generally focused on the adjustment process, on the decision for retirement, and career process evolution (Wang, 2007). Some authors, however, understand well-being in retirement as different from adjustment to retirement. They argue that an individual can adjust to retirement without being satisfied or finding it an advantage (Van Solinge & Henkens, 2008); interest about fluctuation in well-being in this phase of life was recently inaugurated.

Therefore, studying this topic with a focus on well-being is important, although recent studies have concentrated on predictors of adjustment during retirement (Barbosa et al., 2016; Boehs et al., 2017). The current study investigated and systematized information obtained in studies on well-being during retirement by using a systematic literature review of studies that evaluated well-being, happiness, satisfaction, and quality of life, by collection of differences among constructors and adjustment concepts for retirement.

Method

The study search was done electronically by using six online portals: Scielo, PsycInfo, BVS, PubMed, IngentaConnect and Elsevier. Keywords used were retirement (related to retirement) AND positive psychology OR well-being OR satisfaction OR happiness OR quality of life (related with positive psychology), without establishing years of publication. Initially, 403 articles were retrieved: 30 from Scielo, 27 from PsycInfo, 130 from BVS, 67 from PubMed, 84 from Ingenta, and 65 from Elsevier. Table 1 shows inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the analysis of articles.

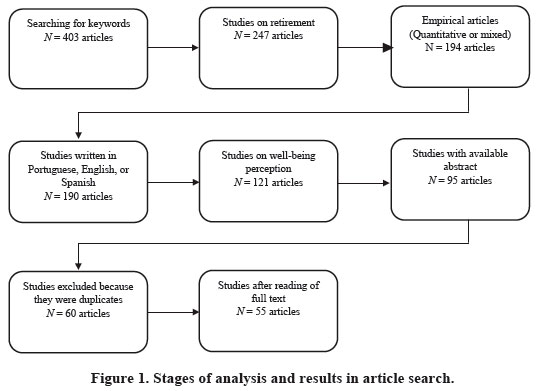

On the basis of inclusion criteria, we excluded 156 of the 403 articles found; this resulted in a sample of 247 articles on retired populations. Subsequently, we excluded articles that included no scientific assessment, those that were not empiric or quantitative, and those with a mixed approach, thereby reducing the sample to 194 articles. Only four articles were written in Portuguese; most were written in English or Spanish. We also excluded 69 articles that did not evaluate well-being, 26 other articles because they lacked a complete abstract, and 35 articles because they were duplicates.

The text of the remaining 60 articles was read to review the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After this review, five additional studies were excluded because they dealt with an elderly population; evaluated well-being using such variables as health, financial situation, and practice of physical activity; or reported on descriptive studies; after these exclusions, 55 articles remained. Figure 1 shows the analysis and selection process of the identified articles.

Results

The 55 articles selected were analyzed by language, year, journal, country where the study was done, objective of the study, dependent variable studied, instruments used and independent variables included in the model. Results were divided into five sessions: date of publication, objectives, dependent variables, independent variables, and results found.

Data of Publications (language, year of publication, location of the study, and types of journal)

All articles were published in English. Almost half of studies (43.7%) were published in 2010 and after, 29.1% were published between 2000 and 2009 and 14.4% were published in the 1990s. A small portion of the articles was published in 1980s (7.3%) or 1970s (5.5%). Approximately half were published in journals on aging or geriatrics and gerontology (47.3%).

Most articles (45.5%) were developed in the United States and Canada, followed in frequency by European countries (23.6%). Six studies were from Australia (10.9%) and five were from East Asia (9.1%). A small percentage of studies were developed in Southwestern Asia (5.4%), Brazil (3.7%) and Nigeria (1.8%).

Objective of Studies (cross-sectional, longitudinal, or validation and creation of instruments)

Articles were classified into three objectives: i) to verify difference between levels of dependent variables at different times, configured as longitudinal studies (34.5%), ii) to verify the influence of independent variables on dependent variables, with a cross-sectional format (56.4%), or iii) to develop, adapt or verify evidence of the validity of an instrument (9.1%). Such classification is presented in Table 2 and is used throughout our study.

Dependent Variables (well-being, satisfaction with life, satisfaction in retirement, happiness and its respective instruments)

In relation to dependent variables investigated, we observed that a greater proportion of articles used constructs: satisfaction with life (37.3%), satisfaction in retirement (29.1%) or psychological well-being (10.1%). A small number of authors worked on the construct of quality of life (7.3%), happiness (3.6%), subjective well-being (3.6%), well-being (3.6%), emotional well-being (1.8%), affect (1.8%) and emotional satisfaction (1.8%; Table 2).

Among the instruments used to measure such variables were questionnaires that consisted of 1 to 7 items and that were developed by the authors (21.8%), the Retirement Satisfactory Inventory (Floyd et al., 1992; 16.6%), and some or all items of the Life Satisfactory Inventory (Neugarten et al., 1961; 16.6%). Only 9% of data used some or all items of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) and the Retirement Descriptive Index (Smith et al., 1969). The Ryff's Psychological Well-Being Scale (1989) was used in 7.3% of papers.

A small percentage of studies used the WHOQOL (1998) scale (3.6%), Continuing Person Questionnaire - HILDA (Melbourne Institute, 2001; 3.6%), Positive and Negative Affect Scale (Watson et al., 1988; 3.6%), Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999; 1.8%), Subjective Well-Being Scale (Cardoso & Ferreira, 2009; 1.8%), CASP-19 Scale (Hyde et al., 2003; 1.8%) and 8 items based on CES-D Scale (Radloff, 1977; 1.8%).

Independent Variables

Among independent variables mentioned in the selected studies, the most cited were health (56.4% of articles), economic situation (50.9%), gender (23.6%), conjugal relationship (13.4%), interpersonal relationships (13.4%), voluntary retirement (12.7%), retirement duration (10.9%) and leisure activities (10.9%).

Few articles mentioned: conjugal relationships (9.1%), continuing to work (7.2%), age (7.2%), engagement in a number of activities (7.2%), places where respondents lived (5.5%), retirement time (5.5%), family relationships (5.5%), physical activities (3.6%), voluntary work (3.6%), feeling of loneliness (3.6%), retirement of a partner (3.6%), bridge employment (3.6%), satisfaction with previous work (3.6%) and type of previous work (3.6%).

Other variables, mentioned in only one article were: previous satisfaction with retirement, values attributed to work, health of partner, loss of partner, job loss before retirement, compulsory retirement, self-transcendence, openness to changes, conservation of values, cognitive resources, motivational resources, management of free time, body satisfaction, motivation to do activities, interference of work in family life, having children living at home, self-employment, self-efficacy, ageism, maintenance of objectives, self-esteem, emotional support, ethnicity, innovative characteristics, prestige in previous work, self-control, having children, sense of humor, living in assisted living residence, age of retirement, demographic density in place where respondent lives, optimism, and free time for activities and hobbies. Each variable corresponded to 1.8% of studies. These results are shown in Table 3.

The data found allowed us to compile independent variables, subdivided into five categories: personal resources, demographic characteristics, activities, previous job, and characteristics of retirement. This compilation is shown in Table 4. The intention was not to limit existing variables. On the contrary, for the number of variables that presented significant effects, it is important to develop studies that continue to explore and test models that include the largest number of possible variables.

Results Found (Cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies and creation and/or validation of instruments)

Cross-Sectional Studies. With regard to cross-sectional studies, in addition to independent variables investigated and mentioned in the previous section, we highlight results found in six studies that analyzed the relationship between variables. One of them showed that the relationship of satisfaction with one's body and satisfaction in retirement was partially measured by subjective health.

The relationships between social support and satisfaction with life of retirees and between social support and quality of leisure time were measured by continuity of goals. For retirees who had limited leisure activities before retirement, the experience of new activities was far more important than continuing the process of adapting to retirement.

Regarding retirement planning, regardless of whether the event was involuntary or voluntary, the preparation for retirement was associated with satisfaction with life. A study whose results should be highlighted was a transcultural study that included workers from South Korea, Germany, and Switzerland. In South Korea, only workers who definitely retired had higher levels of satisfaction with life compared with those who continued working, whereas in Germany and Switzerland those who continued to work had higher levels of satisfaction with life.

Longitudinal Studies. Three longitudinal studies reported positive impact of retirement, and one study found a negative impact. One finding that should be highlighted is that retirement can be more a relief than a stressor for individuals who had a very demanding job that interfered with family life. In the case of stressed families, that did not change with retirement.

In relation to personal resources, receipt of government pension influenced quality of life. For health, persistence in seeking for objectives and flexibility in adjusting to goals in adulthood was beneficial for well-being in retirement. Differences in age, gender, marital and socioeconomic status and resources before retirement influenced levels of well-being after that transition.

Regarding variables related to work, greater planning was associated with an increase in psychological well-being. The degree of occupancy in adult life and standard of participation in the work market influenced well-being in retirement, as did bridge employment, which seemed to be strategy for dealing with involuntary retirement because it can prevent negative changes during retirement. Voluntary retirement was shown as a positive influence on the level of satisfaction after retirement.

Creation Studies or Validation Instruments. In relation to the creation and validation of the instruments we highlighted five studies measured the satisfaction in retirement (Floyd et al., 1992), the retirement resources (Leung & Earl, 2012), satisfaction with life (Bigot, 1974) and the retiree's social identification (Michinov et al., 2008). It has also applied the satisfaction in retirement in a different sample than the original study (Fouquereau et al., 1999). In these studies, reasons to retire, sources of leisure time, and satisfaction with life during retirement were explained by predictors of satisfaction with health and resources, anticipated satisfaction, satisfaction with family and marriage, recovery of liberty and control. The same dimensions had differential functioning for differences in gender, socioeconomic status, time of retirement and bridge employment.

Physical, financial, social, emotional, cognitive and motivational resources added to satisfaction during retirement, in addition to what was explained by demographic variables. Acceptance and retirement had differential functioning to age and socioeconomic status. Social identity of retirees was composed of cognitive, evaluative, and affective components; only the affective component predicted satisfaction with retirement.

Discussion

To investigate and systematize information obtained so far about well-being during retirement, we analyzed 403 papers related to well-being. According to inclusion and exclusion criteria, we included 55 papers, national and international, quantitative or mixed.

Such publications were published in English and most of them were done in North America and Europe, thereby showing the need for studies in South America, Asia, and Africa. Although a substantial number of papers were published between 1970 and 1990, most were published after 2000, based on an increase in concern about the aging population that agreed with beginning of studies in positive psychology (Reppold et al., 2015; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

More than half of selected articles were cross-sectional, one third were longitudinal and only 10% created or validated instruments. We highlight that both longitudinal studies - which facilitate understanding of dynamics of changes in retirement (Dingemans & Henkens, 2015) - and validation instruments studies - which involve beliefs, behaviors, and specific needs (Diener et al., 1985) - were observed only in developed countries.

Still, instrument development seems to be in the validation phase to differentiate populations, most papers used instruments developed for the general population and only three instruments were specific for retirees (Floyd et al., 1992; Neugarten et al., 1961; Smith et al., 1969). In this review, we included only papers that used self-report instruments, according to recommendations for studies of positive psychology (Calvo et al., 2009; Diener et al. 1985).

Independent analysis of variables allowed to conclude that some variables were consolidated in the literature regarding effect on well-being (Amorim et al., 2017; Dingemans & Henkens, 2015; Hershey & Henkens, 2013; Latif, 2011). These variables are health, economic situations, gender, conjugal status, interpersonal relationships, voluntary retirement, time for retirement, and to do leisure activities. A large number of other variables, although investigated with less frequency, presented significant effects on well-being in retirement, which confirms the multidimensional of this construct as mentioned by a number of authors (Barbosa et al., 2016; Boehs et al., 2017; França, 2012; Nalin & França, 2015).

These compiled variables presented five dimensions: demographic variables, personal resources, previous work characteristics, ability to do activities, and characteristics of retirement. Previous work characteristics were included in fewer studies, whereas dimensions related to demographic variables and personal resources were mentioned more often. Regarding the latter, we observed a focus on health and financial conditions in compensation to personal, emotional, and motivational characteristics. The literature seems to progress, therefore, for consensus that health, finances, and social conditions influence how retirement can be assessed in terms of well-being. Continuing results in this sense using different delineations corroborate with the beliefs of many subgroups for retirement (Hershey & Henkens, 2013; Wang, 2007).

We understand that including all independent variables in a single model would be almost impossible because of the number of variables. However, it is fundamental to studies using little consolidation of variables in order to fulfill gaps pointed out in other studies, reinforcing the multi-dimension of well-being in retirement (França, 2012; França et al., 2013).

Analysis of work characteristics and retirement shows not only the impact of involuntary and voluntary retirement (negative and positive, respectively) but also the importance of preparation for retirement in any situation (Calvo et al., 2009; Dingemans & Henkens, 2015). Therefore, planning is confirmed as an important practice that must be stimulated as young people enter the job market (França, 2012; França et al., 2013).

Job standards developed throughout life must be considered to achieve well-being in retirement. Strategies for planning can include the increase of leisure activities (Earl et al., 2015), bridge employment, beginning a new career, or even remaining in the same job (Dingemans & Henkens, 2015; França et al., 2013). Because this job standard can be influenced by culture, it is relevant to perform transcultural studies that evaluate perception of retirement in different contexts (Cho & Lee, 2013; Kim & Moen, 2002).

França (2012) highlighted that retirement can be seen as a time of losses and gains in a positive and negative manner. This assessment, along with individual, demographic and cultural differences, seems to explain both positive and negative results concerning impact of well-being in retirement found in some of the studies selected in this review.

Conclusion

This study achieved its goal of exploring the literature on well-being during retirement and its influences. Gaps remain related to development in this area of study. Some variables related to demographic characteristics (gender, conjugal status), personal resources (health, economic situation, and interpersonal relationships), the characteristics of retirement (voluntary retirement, retirement time) and leisure activities are already consolidated as positively affecting well-being. However, further studies are warranted to approach the complexity of well-being in retirement of studies with longitudinal and transcultural design.

There are number of concepts used in retirement, some of them deal with the same construct. In Brazil, a number of studies are focused on decision process. Internationally, the adjustment process, regardless of satisfaction, seems to have gained more attention (Van Solinge & Henkens, 2008). Although we did not include all possibilities of transition in this review, it is necessary to consider the massive construction of these studies to amplify the knowledge about retirement and direct positive characteristics for this phase of life.

Of note, some limitations of this study do not allow generalizability of its results, such as the fact that the included studies were published in only three languages. In addition, we considered only empirical studies published as scientific articles. Book chapters on the subject were excluded. Such decisions were made with the aim of justifying the search, once free-access platforms were considered only for this type of publication.

Based on scarcity of national studies, we highlight the need of including well-being during retirement as a topic on the agenda of Brazilian researchers. The current lack can be corrected by studies that include the following points: analysis of well-being concepts, adjustment to retirement and decision to retire; development and adaptation of instruments directed for retirees; elaboration and testing of most robust models of investigations that cover different phases of retirement; development of longitudinal studies that may enhance the knowledge on the impact of well-being during retirement; construction of interventional models for pre-retirees and retirees to assess the impact on well-being of their life.

We believe that studies as mentioned above can improve integration sought by positive psychology, constructing knowledge in the urgent domain for society as well as well-being. For studies of retirement, to enhance the view that already exists, few studies have cited as a theory that possibly will contribute to harmonious departure from the job market and a positive perception of the possibilities and accomplishments during retirement.

References

Amorim, S. M., França, L. H. F. P., & Valentini, F. (2017). Predictors of happiness among retired from urban and rural areas in Brazil. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 30(2),1-8. doi: 10.1186/s41155-016-0055-3 [ Links ]

Austrom, M. G., Perkins, A. J., Damush, T. M., & Hendrie, H. C. (2003). Predictor of life satisfaction in retired physicians and spouses. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38,134-141. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0610-y [ Links ]

Barbosa, L. M., Monteiro, B., & Murta, S. G. (2016). Retirement adjustment predictors: A systematic review. Work, Aging and Retirement, 2(2), 262-280. doi: 10.1093/workar/waw008 [ Links ]

Barrett, G. F., & Kecmanovic, M. (2013). Changes in subjective well-being with retirement: Assessing savings adequacy. Applied Economics, 45(35),4883-4893. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2013.806786 [ Links ]

Bell, B. D. (1978). Life satisfaction and occupational retirement: Beyond the impact year. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 9(1),31-50. doi: 10.2190/WK6A-6WXQ-6EWF-TWEG [ Links ]

Bigot, A. (1974). The relevance of American life satisfaction indices for research on British subjects before and after retirement. Age and Ageing, 3(2), 113-121. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4855052 [ Links ]

Boehs, S. T. M., Medina, P. F., Bardagi, M. P., Luna, I. N., & Silva, N. (2017). Revisão da literatura latino-americana sobre aposentadoria e trabalho: Perspectivas psicológicas [Latin-American literature review on retirement and working: Psychological perspectives]. Revista Psicologia, Organizações e Trabalho, 17(1),54-61. doi: 10.17652/rpot/2017.1.11598 [ Links ]

Brajkovic, L., Gregurek, R., Kuevi, Z., Ratkovi, A. S., Bras, M., & Dordevie, V. (2011). Life Satisfaction in Persons of the Third Age after Retirement. Collegium Antropologicum, 35(3),665-671. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22053539 [ Links ]

Burr, A., Santo, J. B., & Pushkar, D. (2009). Affective well-being in retirement: The influence of values, money, and health across three years. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(1),17-40. doi: 10.1007/s10902-009-9173-2 [ Links ]

Calvo, E., Haverstick, K., & Sass, S. A. (2009). Gradual retirement, sense of control, and retirees' happiness. Research on Aging, 31(1),112-135. doi: 10.1177/0164027508324704 [ Links ]

Cardoso, M. C. S., & Ferreira, M. C. (2009). Envolvimento religioso e bem-estar subjetivo em idosos [Religion involvment and subjective well-being in old invididuals]. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 29(2),380-393. doi: 10.1590/S1414-98932009000200013 [ Links ]

Chiang, H., Chien, L., Lin, J., Yeh, Y., & Lee, T. (2012). Modeling psychological well-being and family relationships among retired older people in Taiwan. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(1),93-101. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00840.x [ Links ]

Cho, J., & Lee, A. (2013). Life satisfaction of the aged in the retirement process: A comparative study of South Korea with Germany and Switzerland. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9(2),179-195. doi: 10.1007/s11482-013-9237-7 [ Links ]

Coursolle, K. M., Sweeney, M. M., Raymo, J. M., & Ho, J.-H. (2010). The association between retirement and emotional well-being: Does prior work-family conflict matter? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 65B(5),609-620d doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp116 [ Links ]

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffn, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1),71-4. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [ Links ]

Dijkers, M. P. (2003). Individualization in quality of life measurement: Instruments and approaches. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 84(4, Suppl. 2),3-14. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50241 [ Links ]

Dingemans, E., & Henkens, K. (2015). How do retirement dynamics influence mental well-being in later life? A 10-year panel study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 41(1),16-23. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3464 [ Links ]

Dorfman, L. T. (1995). Health conditions and perceived quality of life in retirement. Health & Social Work, 20(9),192-199. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7557723 [ Links ]

Dorfman, L. T., & Moffet, M. M. (1987). Retirement satisfaction in married and widowed rural women. The Gerontologist, 27(2),215-221. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3583014 [ Links ]

Earl, J. K., Gerrans, P., & Halim, V. A. (2015). Active and adjusted: Investigating the contribution of leisure, health and psychosocial factors to retirement adjustment. Leisure Sciences, 37,354-372. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2015.1021881 [ Links ]

Ejechi, E. O. (2012). The quality of life of retired reengaged academics in Nigeria. Educational Gerontology, 38,328-337. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2010.544601 [ Links ]

Floyd, F. J., Haynes, S. N., Doll, E. R., Winemiller, D., Lemsky, C., Burgy, T. M., Werle, M., & Heilman, N. (1992). Assessing retirement satisfaction and perceptions of retirement experiences. Psychology and Aging, 4(2),609-621. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.4.609 [ Links ]

Fouquereau, E., Fernández, A., & Mullet, E. (1999). The Retirement Satisfactory Inventory: Factor structure in a French sample. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 15(1),49-56. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.15.1.49 [ Links ]

Fouquereau, E., Fernández, A., Paul, M. C., Fonseca, A. M., & Uotinen, V. (2005). Perceptions of and satisfaction with retirement: A comparison of six European Union countries. Psychology and Aging, 20(3),524-528. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.524 [ Links ]

França, L. H. F. P. (2012). Envelhecimento dos trabalhadores nas organizações [Aging of company's workers]. In L. H. F. P. França & D. Stepansky (Eds.), Propostas Multidisplinares para o Bem-estar na Aposentadoria (pp. 25-52). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Quartet. [ Links ]

França, L. H. F. P., Bendassoli, P., Menezes, G. S., & Macedo, L. (2013). Aposentar-se ou continuar trabalhando? O que influencia essa decisão? [Should I retire or continue to work?]. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 33(3),548-563. doi: 10.1590/S1414-98932013000300004 [ Links ]

Gall, T. L., & Evans, D. (2000). Preretirement expectations and the quality of life of male retirees in later retirement. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 32(3),187-197. doi: 10.1037/h0087115 [ Links ]

Gall, T. L., Evans, D. R., & Howard, J. (1997). The retirement adjustment process: Changes in the well-being of male retirees across time. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 52(3),110-117. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52B.3.P110 [ Links ]

Hershey, D. A., & Henkens, K. (2013). Impact of different types of retirement transitions of perceived satisfaction with life. The Gerontologist, 1,1-13. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt006 [ Links ]

Herzog, A. R., House, J. S., & Morgan, J. N. (1991). Relation of work and retirement to health and well-being in older age. Psychology and Aging, 6(2),202-211. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1863389 [ Links ]

Hooker, K., & Ventis, D. G. (1984). Work ethic, daily activities, and retirement satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 39(4),478-484. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.4.478 [ Links ]

Hyde, M., Wiggins, R. D., Higgs, P. F. D., & Blane, D. (2003). A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging & Mental Health, 7(3),186-194. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000101157 [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2018). Tábuas Completas de Mortalidade para o Brasil - 2017 [Complete Mortality Table in Brazil]. Retrieved from https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas-novoportal/sociais/populacao/9126-tabuas-completas-de-mortalidade.html [ Links ]

Iwatsubo, Y., Derriennic, F., Cassou, B., & Poitrenaud, J. (1996). Predictors of life satisfaction amongst retired people in Paris. International Journal of Epidemiology, 25(1),160-170. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8666486 [ Links ]

Ju, Y., Han, K., Lee, H., Lee, J. E., Choi, J. W., Hyun, I. S., & Park, E. (2016). Quality of life and national pension receipt after retirement among older adults. Geriatrics and gerontology, 17(8),1205-1213. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12846 [ Links ]

Kim, J. E., & Moen, P. (2002). Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-Being: A life-course, ecological model. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 57B(3),P212-P222. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.P212 [ Links ]

Kubicek, B., Korunka, C., Raymo, J. M., & Hoonakker, P. (2011). Psychological well-being in retirement: The effects of personal and gendered contextual resources. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2),230-246. doi: 10.1037/a0022334 [ Links ]

Latif, E. (2011). The impact of retirement on psychological well-being in Canada. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40,373-380. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2010.12.011 [ Links ]

Lawton, M. P. (1975). The Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale: A revision. Journal of Gerontology, 30,85-89. doi: 10.1093/geronj/30.1.85 [ Links ]

Leung, C. S. Y., & Earl, J. K. (2012). Retirement Resources Inventory: Construction, factor structure and psychometric properties. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81,171-182. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.06.005 [ Links ]

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46,137-155. doi: 10.1023/A:1006824100041 [ Links ]

Martin, L. A., Fogarty, G. J., & Albion, M. J. (2013). Changes in athletic identity and life satisfaction of elite athletes as a function of retirement status. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 26(1),96-110. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2013.798371 [ Links ]

Melbourne Institute. (2001). The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. Retrieved from http://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/hilda [ Links ]

Michinov, E., Fouquerau, E., & Fernandez, A. (2008). Retirees' social identity and satisfaction with retirement. International Journal in Aging and Human Development, 66(3),175-194. doi: 10.2190/AG.66.3.a [ Links ]

Nalin, C. P., & França, L. H. F. P. (2015). The importance of resilience for well-being in retirement. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 25(61),191-199. doi: 10.1590/1982-43272561201507 [ Links ]

Neugarten, B. L., Havighurst, R. J., & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 16(2),134-143. doi: 10.1093/geronj/16.2.134 [ Links ]

Nguyen, S., Tirrito, T. S., & Barkley, W. M. (2014). Fear as a predictor of life satisfaction in retirement in Canada. Educational Gerontology, 40(2),102-122. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2013.802180 [ Links ]

Nimrod, G. (2007). Expanding, reducing, concentrating and diffusing: Post retirement leisure behavior and life satisfaction. Leisure Sciences: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 29(1),91-111. doi: 10.1080/01490400600983446 [ Links ]

Nimrod, G. (2008). In support of innovation theory: Innovation in activity patterns and life satisfaction among recently retired individuals. Ageing and Society, 28(6),831-846. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X0800706X [ Links ]

Noone, J., O'Loughlin, K., & Kendig, H. (2013). Australian baby boomers retiring 'early': Understanding the benefits of retirement preparation for involuntary and voluntary retirees. Journal of Ageing Studies, 27(1),207-217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.02.003 [ Links ]

O'Brien, G. O. (1981). Leisure attributes and retirement satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66(3),371-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.66.3.371 [ Links ]

Peretti, P. O., & Wilson, C. (1975). Voluntary and involuntary retirement of aged males and their effect on emotional satisfaction, usefulness, self-image, emotional stability, and interpersonal relationships. International of Ageing and Human Development, 6(2),131-138. doi: 10.2190/T70F-XVNW-A0UG-6YMC [ Links ]

Pinquart, M., & Schindler, I. (2007). Changes of life satisfaction in the transition to retirement: A latent-class approach. Psychology and aging, 22(3),442-455. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.442 [ Links ]

Platts, L. G., Webb, E., Zins, M., Goldberg, M., & Netuveli, G. (2015). Mid-life occupational grade and quality of life following retirement: A 16-year follow-up of the French study. Aging & Mental Health, 19(7),634-646. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.955458 [ Links ]

Price, C. A., & Balaswamy, S. (2009). Beyond health and wealth: Predictors of women's retirement satisfaction. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 68(3),195-214. doi: 10.2190/AG.68.3.b [ Links ]

Price, C. A., & Joo, E. (2005). Exploring the relationship between marital status and women's retirement satisfaction. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 61(1),37-55. doi: 10.2190/AG.68.3.b [ Links ]

Quick, H. E., & Moen, P. (1998). Gender, employment, and retirement quality: A life course approach to the differential experiences of men and women. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(1),44-64. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9552271 [ Links ]

Radloff, L. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [ Links ]

Rafalski, J. C., Noone, J. H., O'Loughlin, K., & Andrade, A. L. (2017). Assessing the Process of Retirement: A Cross-Cultural Review of Available Measures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 32(3). doi: 10.1007/s10823-017-9316-6 [ Links ]

Reppold, C. T., Gurgel, L. G., & Schiavon, C. C. (2015). Research in Positive Psychology: A Systematic Literature Review. Psico-USF, 20(2),275-285. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200208 [ Links ]

Robbins, S. B., Lee, R. M., & Wan, T. T. H. (1994). Goal continuity as a mediator of early retirement adjustment: Testing a multidimensional model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41(1),18-26. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.41.1.18 [ Links ]

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57,1069-1081. [ Links ]

Seccombe, K., & Lee, G. R. (1986). Gender differences in retirement satisfaction and its antecedents. Research on Aging, 8(3),426-440. doi: 10.1177/0164027586008003005 [ Links ]

Seligman, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55,5-14. [ Links ]

Sener, A. Terzioglu, R. G., & Karabulut, E. (2007). Life satisfaction and leisure activities during men's retirement: A Turkish sample. Aging & Mental Health, 11(1),30-36. doi: 10.1080/13607860600736349 [ Links ]

Siguaw, J. A., Sheng, X., & Simpson, P. M. (2016). Biopsychosocial and retirement factors influencing satisfaction with life: New perspectives. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 1-22. doi: 10.1177/0091415016685833 [ Links ]

Smith, D. B., & Moen, P. (2004). Retirement satisfaction for retirees and their spouses: Do gender and the retirement decision-making process matter? Journal of Family Issues, 25(2),262-285. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03257366 [ Links ]

Smith, P. C., Kendall, L. M., & Hulin, C. L. (1969). The Measurement of Satisfaction in Work and Retirement: A Strategy for the Study of Attitudes. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. [ Links ]

Stephan, Y., Fouquereau, E., & Fernandez, A. (2008a). Body satisfaction and retirement satisfaction: The mediational role of subjective health. Aging & Mental Health, 12(3),374-381. doi: 10.1080/13607860802120839 [ Links ]

Stephan, Y., Fouquereau, E., & Fernandez, A. (2008b). The relation between self-determination and retirement satisfaction among active retirement individuals. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 66(4),329-345. doi: 10.2190/AG.66.4.d [ Links ]

Van Solinge, H., & Henkens, K. (2008). Adjustment to and satisfaction with retirement: Two of a kind? Psychology and Aging, 23(2),422-434. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.422 [ Links ]

Wang, M. (2007). Profiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: Examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees' psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2),455-474. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.455 [ Links ]

Wang, W., Wu, C., & Wu, C. (2013). Free time management makes better retirement: A case study of retirees' quality of life in Taiwan. Applied Research Quality Life, 9,591-604. doi: 10.1007/s11482-013-9256-4 [ Links ]

Watson, D., Clark, L., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54,1063-1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 [ Links ]

World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Group. (1998). The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science & Medicine, 46(12),1569-1585. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00009-4 [ Links ]

Yeung, D. Y. (2013). Is pre-retirement planning always good? An exploratory study of retirement adjustment among Hong Kong Chinese retirees. Aging & Mental Health, 17(3),386-393. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.732036 [ Links ]

Zhang, S., Tao, F., Ueda, A., Wei, C., & Fang, J. (2013). The influence of health-promoting lifestyles on the quality of life of retired workers in a medium-sized city of Northeastern China. Environmental Health Preventive Medicine, 18(6),458-465. doi: 10.1007/s12199-013-0342-x [ Links ]

Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Lucia Helena de Freitas Pinho França

Universidade Salgado de Oliveira - UNIVERSO, Programa de Pós-graduação em Psicologia

Rua Marechal Deodoro, 217 - Bloco A - Centro

Niterói - RJ , BRASIL, CEP 24030-060

Phone: (21) 2138 4926

E-mail: silvia.miranda.amorim@gmail.com and lucia.franca@gmail.com

Received: 18/08/2017

1st revision: 29/10/2017

Accepted: 29/10/2017

Support: Universidade Salgado de Oliveira; Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ).