Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.23 no.3 São Paulo set./dez. 2021

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPPE14091

10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPPE14091 ARTICLES

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATIOIN

Evidence-based interventions for promoting prosocial behavior in schools: integrative review

Intervenções baseadas em evidências para promover comportamentos pró-sociais em escolas: revisão integrativa

Intervenciones basadas en evidencias para promover las conductas prosociales en las escuelas: revisión integradora

Iara da S. Freitas ; Gabriela E. de Oliveira

; Gabriela E. de Oliveira ; Márcia Helena da S. Melo

; Márcia Helena da S. Melo

University of São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Since the last decades, an increasing number of research in schools have looked towards prosocial behavior, which refers to voluntary actions aimed at benefiting other individuals. This study aimed to describe evidence-based interventions, available in the national and international literature, focused on promoting prosocial behavior in children and adolescents in the school context. An integrative literature review was carried out with searches in ERIC, LILACS, PePSIC, PsycINFO, SciELO, and Scopus databases, resulting in 21 articles. Nineteen studies reported positive effects in promoting prosocial behavior and other assessed outcomes, such as socioemotional skills, disruptive behavior, interpersonal relationships, and academic achievement. Future studies should investigate the sustainability of the interventions in schools, compare efficacy and effectiveness between their different modalities and invest in their development in countries in the southern hemisphere.

Keywords: prosocial behavior; schools; evidence based practice; health promotion; violence prevention.

RESUMO

A partir das últimas décadas, um número crescente de pesquisas em escolas tem voltado atenção a comportamentos pró-sociais, que se referem a ações voluntárias, direcionadas a beneficiar outros indivíduos. O objetivo do presente estudo consiste em descrever intervenções baseadas em evidência, disponíveis na literatura nacional e internacional, voltadas à promoção de comportamentos pró-sociais em crianças e adolescentes no contexto escolar. Foi realizada uma revisão integrativa da literatura com buscas nas bases de dados ERIC, LILACS, PePSIC, PsycINFO, SciELO e Scopus, resultando na inclusão de 21 artigos. Dezenove estudos relataram efeitos positivos das intervenções na promoção de comportamentos pró-sociais e em outros desfechos avaliados, como habilidades socioemocionais, comportamentos disruptivos, relacionamentos interpessoais e desempenho acadêmico. Sugere-se que estudos futuros investiguem a sustentabilidade das intervenções nas escolas, comparem eficácia e efetividade entre suas diferentes modalidades, bem como invistam em seu desenvolvimento em países do hemisfério sul.

Palavras-chave: comportamento pró-social; escolas; prática baseada em evidências; promoção de saúde; prevenção de violência.

RESUMEN

Desde las últimas décadas, un número creciente de investigaciones en las escuelas se han orientado hacia la conducta prosocial, que se refiere a acciones voluntarias destinadas a beneficiar a otras personas. El objetivo de este estudio fue describir intervenciones basadas en evidencia, disponibles en la literatura nacional y internacional, direccionadas a promover conductas prosociales en niños y adolescentes en el contexto escolar. Se realizó una revisión integradora de la literatura con búsquedas en las bases de datos ERIC, LILACS, PePSIC, PsycINFO, SciELO e Scopus, resultando en la inclusión de 21 artículos. 19 estudios presentaron efectos positivos en la promoción de la conducta prosocial y en otros resultados evaluados, como habilidades socioemocionales, conducta disruptiva, relaciones interpersonales y rendimiento académico. Investigaciones futuras deben examinar la sostenibilidad de las intervenciones, comparar eficacia y efectividad entre sus diferentes modalidades e invertir en su desarrollo en el hemisferio sur.

Palabras clave: conducta prosocial; escuelas; practica basada en la evidencia; promoción de la salud; prevención de la violencia.

1. Introduction

Prosocial behaviors are defined as voluntary actions intended to benefit others and are subdivided into categories such as: helping, sharing, and comforting (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Knafo-Noam, 2015). According to the literature, schools made an effort to reduce antisocial behavior, especially over the 1990s, possibly due to social losses caused by aggressiveness, criminality, and delinquency. A growing number of studies has focused on prosocial behavior in recent years, not only to deter violence but also to integrate diversity and build a more empathic, collaborative, and fair society (Aznar-Farias & Oliveira-Monteiro, 2006; Caprara, Alessandri, & Eisenberg, 2012; Gottfredson, 2017; Roche, 2010).

Studies show that prosocial behavior is a protective factor against aggressiveness, peer victimization, and social isolation (Griese & Buhs, 2014; Jung & Schroder-Abé, 2019) and is also a predictor of positive interpersonal relationships and good academic performance (Caprara, Barbaranelli, Pastorelli, Bandura, & Zimbardo, 2000; Bergin, 2018). Authors report different approaches to promote prosocial behavior in schools, such as structural interventions composed of activities added to regular school curriculum or specific practices and quality interactions established between educators and students daily (Embry & Biglan, 2008; Van Ryzin, Roseth, & Biglan, 2020). Lebel and Chafouleas (2010) note that these strategies should be employed ideally starting in early childhood.

The teaching of prosocial behavior in schools may compose social and emotional learning, divided into five main competencies, i.e., self-knowledge, self-regulation, social awareness, responsible decision-making, and relationship skills (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2017). The latter is subdivided into interpersonal and intrapersonal skills, while the first refers to prosocial behaviors (Domitrovich, Durlak, Staley, & Weissberg, 2017).

The literature reports that different definitions, categorizations, and assessment methods have been used in the field (Auné, Blum, Facundo, Lozzia, & Horacio, 2014; Martí-Vilar, Corell-García, & Merino-Soto, 2019). According to Eisenberg and Spinrad (2014), research addressing prosocial behavior dates to the 1960s; however, especially from the 2000s onwards, a new generation of research emerged. More sophisticated statistical methods and more robust study designs were adopted, including longitudinal and experimental studies addressing children and adolescents.

Mesurado, Guerra, Richaud, and Rodriguez (2019) performed a meta-analysis to investigate the programs' effectiveness to promote prosocial behaviors and decrease aggressive behaviors. Inclusion criteria were papers, theses, and dissertations conducted from 2000 to 2017, including experimental and control groups and children and adolescents aged 8 to 18. Ten studies were selected, conducted in North American countries and Europe among 10 to 13-year-old children and adolescents, published from 2008 onwards, using the quasi-experimental design. The interventions were moderate to highly effective in promoting prosocial behavior, and all were effective in preventing aggressive behavior. The authors highlight that the results should be interpreted with caution, considering the different strategies used and methods employed to analyze the effects. They also draw attention to the few studies found and recommended developing interventions to acquire new evidence.

According to Spivak, Lipsey, Farran, and Polanin (2015), literature reviews can summarize evidence regarding interventions that present significant impacts on promoting prosocial behavior among children and adolescents to support the decision-making of professionals, researchers, and policy managers. The authors mentioned earlier note that promoting prosocial behavior at schools is highly relevant in current educational reforms. However, there is a lack of studies reviewing interventional strategies in this field (Mesurado et al., 2019). In this sense, reviews addressing interventions implemented explicitly at schools with children and adolescents at different scientific evidence levels are pertinent. Given the previous discussion, this study's objective was to describe evidence-based interventions intended to promote prosocial behavior among children and adolescents at school available in the Brazilian and international literature.

2. Method

This is an integrative literature review. Therefore, the following question emerged:

• What are the methodological characteristics of the studies and the characteristics of the evidence-based interventions intended to promote prosocial behavior among children and adolescents at schools available in the Brazilian and international literature?

The bibliographic survey was conducted in January 2021 on the following databases: ERIC, LILACS, PePSIC, PsycINFO, SciELO, and Scopus. The following combination of terms and Boolean operators were used in all databases: ("prosocial behavior" OR "helping behavior" OR "sharing behavior" OR "comforting behavior") AND "schools" AND ("intervention" OR "program" OR "trial"). After that, the survey was conducted using the equivalent terms in Portuguese. Filters were used for publication date (2000-2020), type of document (paper), type of source (peer-reviewed journals), and language (Portuguese, English, or Spanish), as the databases allowed.

Inclusion criteria were: 1. articles published in scientific journals between 2000 and 2020; 2. addressing children from 0 to nine years old, and/or adolescents from 10 to 19 years old, or members of the school staff aged 18+; 3. exclusively developed at schools; 4. with interventions intended to promote prosocial behavior; 5. including universal interventions, i.e., implemented to all the individuals of a given school population; 6. evidence-based interventions (experimental, quasi-experimental studies, pre- and posttest with a group, case series, or case reports); 7. published in Portuguese, English or Spanish. Exclusion criteria were: 1. bibliographic reviews and/or meta-analysis; 2. studies assessing the effects of a given intervention on prosocial behavior, though the objective of which was not to promote prosocial behavior; 3. exclusively follow-up studies (i.e., papers presenting only follow-up data, not including the description of interventions, procedures adopted during the implementation of interventions, or results).

Two researchers from the postgraduate program independently performed the bibliographic survey adopting the same procedures. Later, the results were compared to verify the level of agreement in the selection of studies. Afterward, all the papers' titles and abstracts were read, and those that met inclusion criteria were selected. The full text of papers whose abstracts did not provide sufficient information for inclusion/exclusion criteria were read.

The categories proposed for the analysis of papers were: authors, year of publication, country of origin, the definition of prosocial behavior adopted, objectives, prevention focus, study design, number of participants, target-population, age or school grade, assessment instruments, results, follow-up, professional who facilitated the intervention, theoretical perspective, category of targeted prosocial behavior, dosage or duration, components, content, and whether there was a separate curriculum. The studies' content was organized in a spreadsheet according to the previously established categories.

3. Results

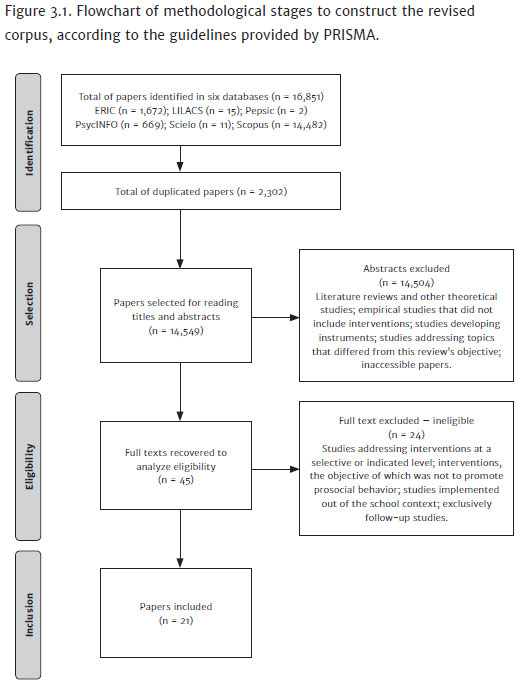

The bibliographic survey resulted in 16,851 papers, 2,302 of which appeared more than once. After implementing the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 14,504 abstracts and the full texts of 24 papers were excluded, so 21 papers remained. The level of consensual agreement between the two researchers was 100%. The process of establishing the revised corpus followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and is summarized in Figure 3.1.

3.1 Studies' methodological characteristics

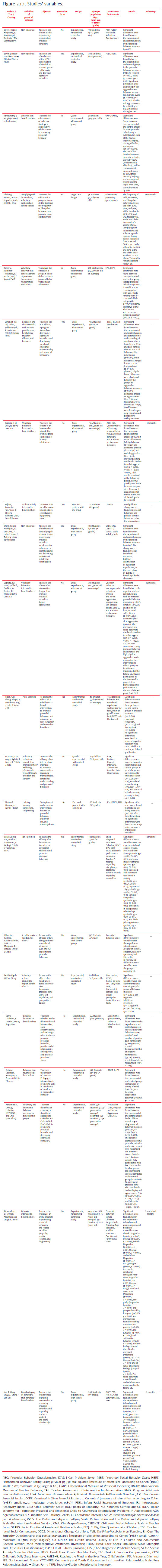

Regarding the studies' publication date, the results showed an increase from 2011 onwards, when 18 (86%) out of the 21 papers selected were published. Regarding country of origin, the studies were developed in the United States (n=4; 19%), Italy (n=4; 19%), Spain (n=2; 9.5%), Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, France, Japan, and Tanzania. One (4.7%) paper was published in each of the last nine countries. Two studies (n=2; 9.5%) addressed samples from two countries: Colombia and Chile, and Argentina and Uruguay.

Regarding the definition of prosocial behavior adopted, the results show that 13 papers (61.8%) presented a definition aligned with voluntary actions intended to benefit others. Two studies (9.5%) presented examples of prosocial behaviors as the definition itself; one (4.7%) adopted a concept that differs from the remaining studies, such as following instructions and voluntary participation in class; while five (24%) studies did not provide a definition.

The studies' primary purposes were to assess the effects (n=8; 38%), efficacy (n=6; 29%), and effectiveness (n=4; 19%) of interventions intended to promote prosocial behavior; three (14%) did not specify the type of assessment performed. Of the 21 interventions addressed, seven (33%) promoted prosocial behavior as the only objective. In contrast, 14 (67%) combined the development of cognitive and social-emotional skills, resilience, quality of life, and metacognition, improved interpersonal relationships, and decreased adverse outcomes, such as disruptive behaviors and stress. Among the interventions addressed, only three (14%) reported a preventive objective. That is, besides health promotion through the strategies previously mentioned, the studies also intended to prevent or decrease aggressive behavior and bullying/victimization.

Most studies adopted the quasi-experimental design, with control (n=9; 42.9%) and experimental groups (n = 9; 42.9%), followed by pre- and posttest with a single group (n=2; 9.5%), and case study (n=1; 4.7%). Sample sizes ranged from 21 to 596 participants, with children and adolescents as the target population, enrolled in equivalent school grades, in the Brazilian context, from early childhood to high school, though mostly focused on primary and middle school. The instruments used included observation, peer nomination techniques, cognitive tasks, and standardized instruments, such as scales and inventories.

Regarding the interventions' results, 19 (90%) presented statistically significant differences in promoting prosocial behavior between the experimental and control groups. Of these, 13 reported effects such as the development of cognitive and social-emotional skills, an increase in pleasant feelings, improved quality of interpersonal relationships at school, and improved student academic performance, decreased aggressive behaviors, stress, anxiety, hyperactivity, and somatic complaints; and 12 (57%) studies reported data regarding effect size, which ranged from small to large.

Four studies (19%) presented statistical analyzes concerning variables mediating and moderating the effects of interventions. The studies show that increased prosocial behaviors mediated decreased physical and verbal aggression or improved the quality of relationships between teachers and students and among students. In turn, three studies highlighted that a less elaborated repertoire of prosocial behaviors along with high measures of physical aggression at the baseline moderated the effects, positively affecting the results of interventions, while high scores obtained at baseline for prosocial behavior and the participants' high socioeconomic level negatively influenced the effects.

Additionally, six (13.3%) out of the 21 studies report follow-up data; the interval of time ranged from one to 18 months. Of these, five maintained the effects in the period, while one maintained the effects only partially. Figure 3.1.1 presents information regarding the variables of the included studies.

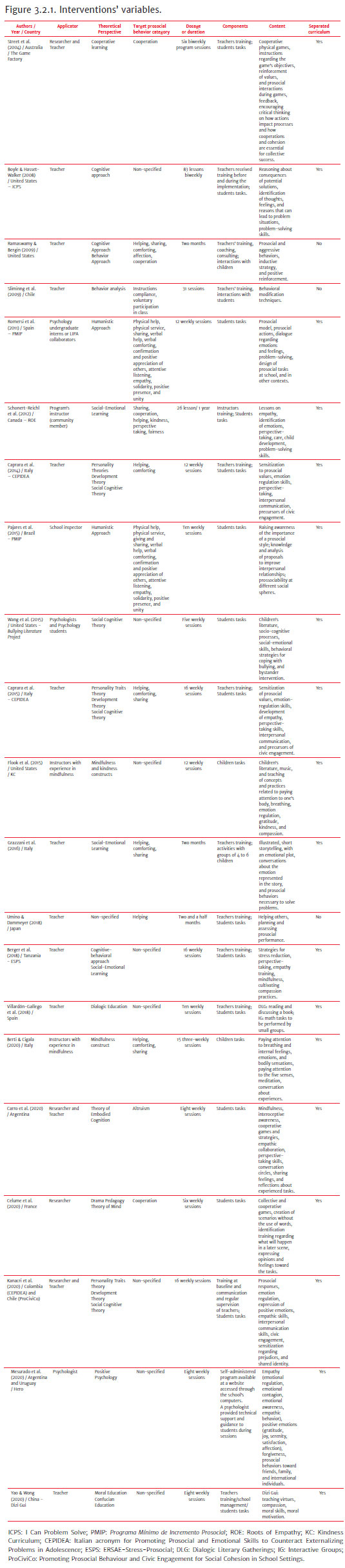

3.2 Interventions' characteristics

Teachers were the professionals facilitating ten (48%) of the interventions, followed by psychologists or interns of Psychology programs, teachers together with researchers, instructors qualified for the program, student inspectors, and researchers only. The theoretical perspectives that grounded the interventions were Cognitive and Behavioral Approaches, Social Cognitive Theory, Social-Emotional Learning, Mindfulness Construct, and Humanistic Approaches, among other frameworks from the fields of Psychology and Education. Note that eight (38%) studies adopted more than one theory, and only one (4,7%) did not explicitly report the theoretical perspective grounding the intervention.

Regarding the categories of prosocial behaviors targeted, 13 studies (62%) specified these categories, while helping, sharing, and comforting were the most frequently used. The interventions lasted from six weeks to one year, while interventions were implemented once a week in 13 (62%) studies, biweekly in one study (4,7%), three-weekly sessions in another study (4,7%), every two weeks in one study (4,7%), while five (23,8%) studies did not report how frequently interventions were implemented. Regarding components, all the interventions (100%) involved practices or tasks with students, 13 (62%) provided training to the facilitators before implementation, and three studies provided support throughout the process. Only one (4,7%) intervention was implemented online.

Content that composed the interventions was related to values, models, prosocial behavior, perspective-taking skills, social-emotional components, problem-solving skills, mindfulness, cooperative strategies, positive feelings (e.g., gratitude, joy, serenity), and moral behavior. Eighteen (86%) interventions had a curriculum to be added to the school planning. In comparison, three (14%) interventions did not establish a specific number of sessions, lessons, or tasks. Instead, they included cognitive or behavioral techniques or instructions to be adopted by educators toward students at different times during the daily routine. Figure 3.2.1 presents information regarding the interventions' variables.

4. Discussion

An increase in the number of studies addressing interventions focused on promoting prosocial behavior at schools was observed from 2004 onwards, corroborating the findings reported by Mesurado et al. (2019) and marking a new generation in the field, as noted by Eisenberg and Spinrad (2014). Regarding the authors' affiliation, even though most studies were conducted in the Northern hemisphere, there was an advance in terms of the geographical distribution of programs compared to the results reported by Mesurado et al. (2019). Thus, this review includes studies conducted in all the continents, suggesting the importance of promoting prosocial behavior in schools, regardless of cultural differences. There were also studies addressing programs initially developed in Europe and later adapted to Latin American countries.

Note that the strategy adopted here to include studies with different levels of scientific evidence, rather than only experimental or quasi-experimental studies with control groups, may have contributed to selecting a more significant number of studies. Among the studies developed in the Southern hemisphere, only one was conducted in Brazil. According to Aznar-Farias and Oliveira-Monteiro (2006), few studies address interventions in the field of prosocial behavior in that country, which is confirmed in this review. The authors mentioned earlier also note that constructs addressed in the programs that more closely resemble the topic in Brazil include social skills and social competence.

Regarding the definition of prosocial behavior, the one aligned with Eisenberg, Fabes, and Spinrad (2006) was the most frequently used, though variations, or even no definition, were also found. According to Bergin (2018), the term prosocial behavior is often conceived from a more comprehensive perspective, such as positive social behavior, which may accrue from an expanded use and even an imprecise appropriation. The hypothesis is that this concept of the term may have been adopted by the studies that did not report a definition of prosocial behavior.

Regarding the interventions' objectives and results, in addition to prosocial behaviors, three studies also intended to decrease or deter aggression and bullying/victimization, which were classified as preventive interventions. Note that, even though the remaining studies did not identify their interventions as such, some assessed outcomes related to disruptive behaviors obtained positive results, confirming evidence reported by Mesurado et al. (2019). According to these authors, strengthening resources such as prosocial behaviors effectively prevent problem behavior in the school context.

Note that the studies addressed in this review described other effects besides the ones previously mentioned, such as the development of cognitive and social-emotional skills, improved quality of interpersonal relationships and academic performance, increased frequency of pleasant feelings, and a decrease in mental health problems. These results suggest a good cost-benefit, and therefore, are relevant for public managers making decisions on whether to adopt such interventions (Bartholomew-Eldredge et al., 2016; Spivak et al., 2015). Additionally, it is worth noting that the relationship between the promotion of prosocial behavior and the remaining outcomes is consonant with the literature regarding the potential of prosocial behaviors in establishing school environments that support the individuals' integral development (Caprara et al., 2012; Gottfredson, 2017; Roche, 2010).

The studies present significant differences concerning designs, sample sizes, and instruments used for assessments, which reveal methodological heterogeneity. This finding confirms that comparing the results among studies in the field of prosocial behavior is a challenging task. This difficulty accrues from the construct's conceptual diversity - partially explained by its complexity - and the fact that the instruments are based on different definitions and categorizations (Auné et al., 2014; Martí-Vilar et al., 2019), with implications for research planning.

Most of the studies were developed among students 6+ years old. In this sense, Lebel and Chafouleas (2010) conducted a literature review and reported that, despite their importance, fewer interventions are promoting prosocial behavior in early childhood education (i.e., children aged from zero to five). It may be related to the fact that knowledge regarding this topic is seldom disseminated to educators in this teaching stage. According to the authors mentioned earlier, systematic effort on the part of professionals from the Psychology field, together with researchers, educators, and families, is required to advance in the development of interventions that promote prosocial behavior in early childhood education.

Note that more than half of the studies reported that the interventions' components included tasks performed with students and training provided to the teachers before the interventions. The literature highlights that implementing evidence-based interventions in schools may be challenging, considering acceptance of studies, communication among the various stakeholders, flexibility and availability of teachers and other workers, the need to adjust the school schedule, and limited resources, among others. In this sense, knowledge regarding the context where one wishes to implement an intervention, empathy, and the establishment of collaborative partnerships, transparency, and trust is required between researchers and school community members (Marturano, Bolsoni-Silva, & Santos, 2015; Biglan, 2004).

In addition to the interventions varying in terms of theoretical perspectives, content, duration, and formats, some interventions proposed that activities were added to the regular school curriculum, while others implemented interventions throughout routine interactions. According to Van Ryzin et al. (2020), this second possibility may incur fewer costs associated with curriculum and time adaptation. Embry and Biglan (2008) defend that more straightforward practices, instead of complex interventions, might more easily be adopted and implemented by professionals in practice, favoring disseminating knowledge and the outcome of planned actions. Nonetheless, and considering that 19 out of the 21 interventions analyzed here presented positive results, the hypothesis is that different models of interventions can promote prosocial behavior at schools.

This study's limitations include the restricted number of languages imposed on the selection of studies, time of publication, and the exclusion of inaccessible studies, which may have led to a lower number of studies. In this sense, we suggest that future reviews include papers and theses and dissertations and consider interventions focused on social-emotional skills, investigating whether the promotion of prosocial behaviors is part of their objectives, which may expand the number of studies selected.

It is also essential to consider that the growing number of evidence-based interventions conducted in recent years with children in the field of prosocial behavior indicates a process of construction and improvement of a new generation of research and represents advancement. Future research should investigate the sustainability of interventions at schools over time, compare efficacy and effectiveness between different modalities, invest in cultural adaptations, and develop and assess more interventions in countries where these interventions are still incipient, as is Brazil's case.

Finally, identifying interventions intended to promote prosocial behavior at schools in this review is expected to support managers' decision-making to plan and develop strategies according to the context involving the health and educational sectors. Additionally, this study can guide new research and support the practice of educators and psychologists working in the school context.

References

Auné, S. E., Blum, D., Facundo, J. P. A., Lozzia, G. S., & Horacio, F. A. (2014). La conducta prosocial: Estado actual de la investigación. Perspectivas en Psicología: Revista de Psicología y Ciencias Afines, 11(2),21-33. Retrieved from https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=483547666003 [ Links ]

Aznar-Farias, M., & Oliveira-Monteiro, N. R. (2006). Reflexões sobre pró-socialidade, resiliência e psicologia positiva. Revista Brasileira de Terapias Cognitivas, 2(2),39-46. doi: 10.5935/1808-5687.20060015 [ Links ]

Bartholomew-Eldredge, L. K., Markham, C. M., Ruiter, R. A. C., Fernández, M. E, Kok, G., & Parcel, G. S. (2016). Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach (4th ed.). São Francisco: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Berger, R., Benatov, J., Cuadros, R., VanNattan, J., & Gelkopf, M. (2018). Enhancing resiliency and promoting prosocial behavior among tanzanian primary-schools students: A school-based intervention. Transcultural Psychiatry, 55(6),821-845. doi: 10.1177/1363461518793749 [ Links ]

Bergin, C. (2018). Designing a prosocial classroom: Fostering collaboration in students from pre-k-12 with the curriculum you already use. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Berti, S., & Cigala, A. (2020). Mindfulness for preschoolers: Effects on prosocial behavior, self-regulation and perspective taking. Early Education and Development. Ahead of print. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2020.1857990 [ Links ]

Biglan, A. (2004). Contextualism and the development of effective prevention practices. Prevention Science, 5(1),15-21. doi: 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013977.07261.5a [ Links ]

Boyle, D., & Hassett-Walker, C. (2008). Reducing overt and relational aggression among young children. Journal of School Violence, 7(1),27-42. doi: 10.1300/J202v07n01_03 [ Links ]

Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., & Eisenberg, N. (2012). Prosociality: The contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6),1289-1303. doi: 10.1037/a0025626 [ Links ]

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2000). Prosocial foundations of children's academic achievement. Psychological Science, 11(4),302-306. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00260 [ Links ]

Caprara, G. V., Kanacri, B. P. L., Gerbino, M., Zuffianò, A., Alessandri, G., Vecchio, G., Caprara, E., Pastorelli, C., & Bridglall, B. (2014). Positive effects of promoting prosocial behavior in early adolescence: Evidence from a school-based intervention. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(4),386-396. doi: 10.1177/0165025414531464 [ Links ]

Caprara, G. V., Kanacri, B. P. L., Zuffianò, A., Gerbino, M., & Pastorelli, C. (2015). Why and how to promote adolescents' prosocial behaviors: direct, mediated and moderated effects of the CEPIDEA school-based program. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(1),2211-2229. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0293-1 [ Links ]

Carro, N., D'Adamo, P., & Lozada, M. (2020). An effective intervention can contribute to enhancing social integration while reducing perceived stress in children. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 18(1),183-201. Retrieved from http://ojs.ual.es/ojs/index.php/EJREP/article/view/2600/3457 [ Links ]

Celume, M. P., Goldstein, T., Besançon, M., & Zenasni, F. (2020). Developing children's socio-emotional competencies through drama pedagogy training: An experimental study on theory of mind and collaborative behavior. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 16(4),707-726. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v16i4.2054 [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (2017). Social and emotional learning (SEL) competencies. Chicago: Casel. Retrieved from https://casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/CASEL-Competencies.pdf [ Links ]

Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Social-emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Development, 88(2),408-416. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12739 [ Links ]

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A, & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg (Org.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 646-718). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Eisenberg, N., & Spinrad, T. L. (2014). Multidimensionality of prosocial behavior: Rethinking the conceptualization and development of prosocial behavior. In L. M. Padilla-Walker & G. Carlo (Orgs.), Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach (pp. 17-39). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Knafo-Noam, A. (2015). Prosocial development. In M. E. Lamb & R. M. Lerner (Orgs), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: socioemotional processes (Vol; 3, pp. 610-656). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Embry, D. D., & Biglan, A. (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology, 11(3),75-113. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x [ Links ]

Flook, L., Goldberg, S. B., Pinger, L., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based kindness curriculum. Developmental Psychology, 51(1),44-51. doi: 10.1037/a0038256.supp [ Links ]

Gottfredson, D. C. (2017). Prevention research in schools: Past, present, and future. American Society of Criminology, 16(1),6-27. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12280 [ Links ]

Grazzani, I., Ornaghi, V., Agliati, A., & Brazzelli, E. (2016). How to foster toddlers' mental-state, talk, emotion understanding, and prosocial behavior: a conversation-based intervention at nursery school. Infancy, 21(2),199-227. doi: 10.1111/infa.12107 [ Links ]

Griese, E. R. M., & Buhs, E. S. (2014). Prosocial behavior as a protective factor for children's peer victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(7),1052-1065. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0046-y [ Links ]

Jung, J., & Schroder-Abé, M. (2019). Prosocial behavior as a protective factor against peers' acceptance of aggression in the development of aggressive behavior in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 74(1),146-153. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.06.002 [ Links ]

Kanacri, B. P. L., Zuffiano, A., Pastorelli, C., Jiménez-Moya, G., Tirado, L. U., Thartori, E., Gerbino, M., Cumsille, P., & Martinez, M. L. (2020). Cross-national evidences of a school-based universal programme for promoting prosocial behaviours in peer interactions: Main theoretical communalities and local unicity. International Journal of Psychology, 55(1),48-59. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12579 [ Links ]

Lebel, T. J., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2010). Promoting prosocial behavior in preschool: A review of effective intervention supports. School Psychology Forum, 4(2),25-38. Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spf/volume-4/volume-4-issue-2-(summer-2010)/promoting-prosocial-behavior-in-preschool-a-review-of-effective-intervention-supports [ Links ]

Martí-Vilar, M., Corell-García, L., & Merino-Soto, C. (2019). Systematic review of prosocial behavior measures. Revista de Psicología, 37(1),349-377. Retrieved from http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=14&sid=9ec01324-b41c-4f03-9f6f-b487df613cc5%40sdc-v-sessmgr03 [ Links ]

Marturano, E. M., Bolsoni-Silva, A. T., & Santos, L. C. (2015). Intervenções na escola. In S. G. Murta, C. Leandro-França, & L. Polejack (Orgs.), Prevenção e promoção em saúde mental (pp. 520-537). Novo Hamburgo: Sinopsys. [ Links ]

Mesurado, B., Guerra, P., Richaud, M. C., & Rodriguez, L. M. (2019). Effectiveness of prosocial behavior interventions: A meta-analysis. In P. A. Gargiulo & H. L. M. Arroyo (Orgs.), Psychiatry and neuroscience update (pp. 259-271). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-95360-1_21 [ Links ]

Mesurado, B., Oñate, M. E., Rodriguez, L. M., Putrino, N., Guerra, P., & Vanney, C. E. (2020). Study of the efficacy of the Hero program: cross-national evidence. PloS One, 15(9),e0238442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238442 [ Links ]

Pajares, R. C., Aznar-Farias, M., Tucci, A. M., & Oliveira-Monteiro, N. R. (2015). Comportamento prossocial em adolescentes estudantes: Uso de um programa de intervenção breve. Temas em Psicologia, 23(2),507-519. doi: 10.9788/TP2015.2-20 [ Links ]

Ramaswamy, V., & Bergin, C. (2009). Do reinforcement and induction increase prosocial behavior? Results of a teacher-based intervention in preschools. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 23(4),527-538. doi: 10.1080/02568540909594679 [ Links ]

Roche, O. R. (2010). Prosocialidad, nuevos desafios: Métodos y pautas para la optimización creativa del entorno. Buenos Aires: Ciudad Nueva. [ Links ]

Romersi, S., Martínez-Fernández, J. R., & Roche, R. (2011). Efectos del Programa Mínimo de Incremento Prosocial em uma muestra de estudiantes de educación secundária. Anales de Psicología, 27(1),135-146. Retrieved from https://revistas.um.es/analesps/article/view/113561 [ Links ]

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Smith, V., Zaidman-Zait, A., & Hertzman, C. (2012). Promoting children's prosocial behaviors in school: Impact of the "Roots of Empathy" program on the social and emotional competence of school-aged children. School Mnetal Health, 4(1),1-21. doi: 10.1007/s12310-011-9064-7 [ Links ]

Sliminng, E. C., Montes, P. B., Bustos, C. F., Hoyuelos, X. P., & Vio, C. G. (2009). Efectos de um programa combinado de técnicas de modificación conductual para la disminución de la conducta disruptiva y el aumento de la conducta prosocial em escolares chilenos. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 12(1),67-76. Retrieved from https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/798/79814903006.pdf [ Links ]

Spivak, A. L., Lipsey, M. W., Farran, D. C., & Polanin, J. R. (2015). PROTOCOL: Practices and program components for enhancing prosocial behavior in children and youth: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 11(1),1-105. doi: 10.1002/CL2.145 [ Links ]

Street, H., Hoppe, D., Kingsbury, D., & Ma, T. (2004). The game factory: Using cooperative games to promote pro-social behaviour among children. Australian Journal of Educational & Development Psychology, 4(1),97-109. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ815556.pdf [ Links ]

Umino, A., & Dammeyer, J. (2018). Effects of a danish student-centered prosocial intervention program among japanese children. Japanese Psychological Research, 60(2),77-86. doi:0.1111/jpr.12183 [ Links ]

Van Ryzin, M. J., Roseth, C. J., & Biglan, A. (2020). Mediators of effects of cooperative learning on prosocial behavior in middle school. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 1(1),1-16. doi: 10.1007/s41042-020-00026-8 [ Links ]

Villardón-Gallego, L., García-Carrión, R., Yañez-Marquina, & Estévez, A. (2018). Impact of the interactive learning environments in children's prosocial behavior. Sustainability, 10(7),1-12. doi: 10.3390/su10072138 [ Links ]

Wang, C., Couch, L., Rodriguez, G. R., & Lee, C. (2015). The Bullying Literature Project: Using children's literature to promote prosocial behavior and social-emotional outcomes among elementary school students. Contemporary School Psychology, 19(1),320-329. doi: 10.1007/s40688-015-0064-8 [ Links ]

Yao, Z., & Wong, L. (2020). The effect of the Dizi Gui intervention on peer relationships and teacher-student relationships: The mediating role of prosocial behavior. Journal of Moral Education. Ahead of print. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2020.1722080 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Silva Freitas

Instituto de Psicologia (bloco F, sala 19)

Avenida Professor Mello Moraes, 1721, Cidade Universitária

São Paulo-SP. CEP 05508-030

E-mail: iarafreitas.psi@gmail.com

Submission: September 30th, 2020

Acceptance: March 16th, 2021

Authors' notes: Iara da S. Freitas, Institute of Psychology, University of São Paulo (USP); Gabriela Eustáquio de Oliveira, Institute of Psychology, USP; Vanessa da S. Lima, Institute of Psychology, USP; Márcia Helena da S. Melo, Institute of Psychology, USP.