Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can occur when specific symptoms develop. Intrusive and recurrent memories of the traumatic event, intense physiological reactions to stimuli that resemble the traumatic event, dissociative reactions, and hypervigilant behavior present for more than a month after exposure to one or more traumatic events are examples of them (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

It is noticed that not all exposure to a traumatic event leads to PTSD. An analysis of data from the World Health Organization collected in 24 countries (n=68,894) found that 70.4% of people had experienced at least one traumatic event throughout their lives and the average risk for developing PTSD was 4%. However, there was a highest conditional risk associated with being raped (19.0%), physically abused by a romantic partner (11.7%), kidnapped (11.0%), and sexually assaulted (other than rape) (10.5%) (Kessler et al., 2017).

To help people suffering from PTSD, many therapies claim to be effective. Examples of such treatments include seeking safety (Tripodi et al., 2017), somatic experiencing (Kuhfuß et al., 2021), attention bias modification (Alon et al., 2022), psychoeducation (Mughairbi et al., 2019), brief eclectic psychotherapy (Gersons et al., 2020), emotional freedom techniques (Church et al., 2018), interpersonal psychotherapy (Althobaiti et al., 2020), reconsolidation of traumatic memories (Gray et al., 2017), written emotional disclosure (Thompson-Hollands et al., 2019), and present-centered therapy (Belsher et al., 2019).

Because of numerous supposedly effective therapies, many countries developed practice guidelines to assist practitioners in choosing the most effective ones (Forbes et al., 2010). These guidelines are based on an analysis of the literature in the area and they use, when available, systematic reviews of evidence from large, well-conducted studies that include randomized controlled trials and replication in a clinical setting (Forbes et al., 2010).

Thus, this study had two objectives, first to conduct a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for PTSD, and second, to compare the intervention strategies of these therapies. Therefore, its specific objectives were researching clinical practice guidelines that performed systematic reviews of psychological therapies for treating adults with PTSD compared to other psychological therapies; selecting the most recommended ones by the guidelines; identifying the intervention strategies of each therapy; and comparing them. Comparison of the strategies used in proven-effective approaches for PTSD may allow the identification of common principles among them, increasing the understanding of what is essential for treating this disorder.

METHOD

This systematic literature review follows the PRISMA recommendations (Moher et al., 2009). This review did not register its protocol in a systematic reviews registry database. The terms were searched in the following search engines, with the databases in parentheses: PubMed (MedLine); PsycNet (PsycInfo, PsycArticle, and PsycBooks); Web of Science (Core Collection); BVS-PSI (Index Psi); BVS-PSI (LILACS); SciELO (SciELO Brazil); SciELO (PePSIC).

The search terms used the keywords “guideline” and “post-traumatic stress disorder” with variations in English and Portuguese. In English: (guideline OR guidelines) AND (ptsd OR ((posttraumatic OR “post-traumatic” OR “post traumatic”) AND stress AND disorder)). In Portuguese: (diretriz OR diretrizes) AND (tept OR (transtorno AND estresse AND (“pós-traumático” OR “pós traumático”))).

To find papers that defined clinical practice guidelines and did not just cite other ones, the search terms were limited to titles and abstracts. The papers included were those published in the last 10 years, which performed a systematic review of psychological therapies for PTSD and defined guidelines for clinical practice to treat this disorder in adults. We have excluded duplicate papers, those that did not review cognitive-behavioral therapies, and the ones whose language was not Portuguese or English.

In the identification phase, the search terms were used in each database and the results were saved in the format available from the website (csv, txt, and html). A computer program was created to read these different formats and unify them in a single excel table. This program automatically identified articles with the same doi/pmid, showing when they were duplicated, and analyzed their titles and abstracts, looking for similar articles and asking for confirmation whether they were duplicates.

In the screening phase, the program presented the available data for each study, and then exclusion categories were created to classify them, as the data was read. In the eligibility phase, the studies were accessed via the Periódicos CAPES system or official website, when available, and read to determine eligibility. In the included phase, we have used complementary sources from the references of the selected studies, and Google (not Scholar), searching the term “PTSD guidelines”.

We recognize the possibility of risk of bias because of the selection of studies being made by a single author, and the exclusion of articles that were not in English or Portuguese. Regarding cumulative evidence, there is a bias related to the availability of articles at the time the guidelines were written. The method for assessing risk of bias of individual studies from the clinical practice guidelines included in this review were described in the results.

Once the guidelines were identified, they were read completely and carefully to identify their recommended therapies. If there was a discrepancy in the recommendations between the guidelines, we would discuss which of them would be analyzed. Once the therapies were selected, they were analyzed according to the Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) of their intervention strategies to group them into categories.

RESULTS

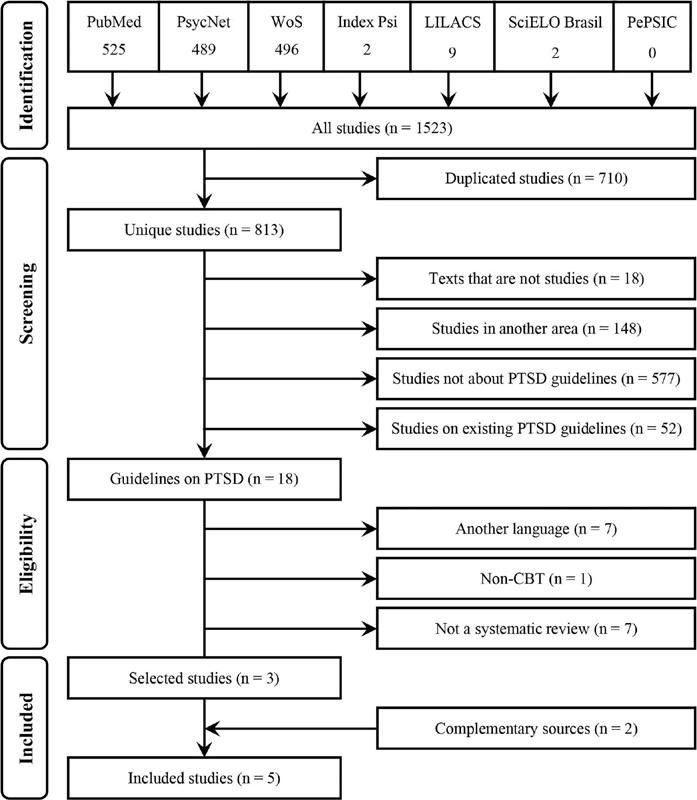

Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the systematic review. From 1,523 studies, five guidelines were identified that recommend therapies to treat PTSD. Two of the guidelines were found from a complementary source, the American Psychological Association guideline was found because it was cited by the other guidelines; the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia guideline is the most recent, it was available on their website and it was found by searching on Google.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of PTSD in adults, between 2010 and 2020, following PRISMA recommendation Note. WoS = web of science; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; CBT = cognitive-behavioral therapy.

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2013) used the GRADE system for assessing the quality of the evidence and developed a profile, including a discussion of values, preferences, benefits, harms, and feasibility. The strength of their recommendation was defined as strong, standard, or not applicable.

The panel analyzed four treatments, and all received standard recommendations: individual trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), group TF-CBT, and stress management. The former two had a moderate quality of evidence and the latter two had a low quality of evidence.

American Psychological Association

The American Psychological Association (APA, 2017a) set guidelines using methods recommended by the Institute of Medicine report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, which uses a modified version of the GRADE system for assessing quality of evidence. The strength of their recommendation was defined as strong, when the panel recommends the treatment; conditional, when the panel suggests the treatment; or insufficient, when there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the treatment.

The panel has analyzed 12 treatments, although only three were listed in the appendix, and seven received the highest recommendation strengths. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), cognitive therapy (CT), and prolonged exposure therapy (PE) received strong recommendations. EMDR, narrative exposure therapy (NET), and brief eclectic psychotherapy received conditional recommendations.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2018) used the GRADE system for assessing the quality of the evidence. They also employed a network meta-analysis and assessed cost-effectiveness to define their recommendations. The strength of the recommendation for each treatment was not organized in a summarized way, but we could identify the following classifications in the text: strong; weak; research; negative; inferior to recommended interventions; limited evidence of effectiveness; limited evidence for neither significant benefits nor harms; and no evidence.

The panel has analyzed 24 treatments, and four received the highest strength of recommendation. Individual TF-CBT and EMDR received strong recommendations. Non-trauma-focused CBT (NTF-CBT) and self-help with support, specifically for supported computerized TF-CBT, received a weak recommendation.

International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies ([ISTSS]; Bisson et al., 2019) used the GRADE system for assessing quality of evidence and defined five levels of recommendation: strong, standard, low effect, emerging evidence, and insufficient evidence.

The panel has analyzed 29 treatments, and ten received the highest strength of recommendation. CPT, CT, EMDR, individual TF-CBT, and PE received strong recommendations. CBT without a trauma focus (NTF-CBT), group TF-CBT, guided internet-based TF-CBT, NET, and present-centered therapy received standard recommendations.

National Health and Medical Research Council

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC, 2020) has updated ISTSS guidelines with more recent systematic reviews. They have used the GRADE methodology and defined five levels of recommendation: strong recommendation for use, conditional recommendation for use, strong recommendation against use, conditional recommendation against use, and recommendation for further research.

The panel has analyzed 18 treatments, and ten received the highest strength of recommendation. CPT, CT, EMDR, PE, and individual TF-CBT received strong recommendations. NET, PCT, SIT, group TF-CBT, and guided internet-based TF-CBT received conditional recommendations.

DISCUSSION

Selecting Treatments for Thematic Analysis

To select the most appropriate therapies for treating PTSD, this section will discuss treatments that have received the highest strengths of recommendation from the guidelines. Therefore, the following therapies were selected for analysis: cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), cognitive therapy (CT), prolonged exposure therapy (PE), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), stress management, stress inoculation training (SIT), narrative exposure therapy (NET), present-centered therapy (PCT), and brief eclectic psychotherapy (BEP).

All the guidelines recommended categories of therapies, not just individual ones. This seems to be because therapies within a category work similarly and, therefore, should have similar results. However, the systematic reviews themselves showed results contrary to this idea.

The ISTSS, which strongly recommended the use of TF-CBT, illustrated this problem well. This category was composed of nine therapies, eight of which were also reviewed individually by the institution. They were recommended as strong (3), standard (2), emerging evidence (2), and insufficient evidence (1). Therefore, not all therapies which are claimed to be TF-CBT should be strongly recommended for PTSD, as well as the nine therapies belonging to this category should also not be strongly recommended for it, only those that were individually analyzed and received strong recommendations. Thus, this paper will not discuss categories, only therapies analyzed individually.

The category CBT, for instance, is a classification that encompasses therapies that have certain characteristics in common, but that may have different theories and practices, so one cannot speak of the existence of a single CBT (Vieira & Rubino, 2018). For a therapy that is called CBT to be effective for a particular disorder, one should consider each therapy in its specificity and not CBT as an umbrella term for several treatments as if they were one (Twohig et al., 2013).

Stress management and CBT were not selected for the thematic analysis because they were actually categories. The latter has always been referred to in the guidelines as a category, whether trauma-focused, non-trauma-focused, or the broader category that encompasses both.

SIT received only one conditional recommendation from NHMRC. PCT received one standard recommendation from ISTSS and one conditional recommendation from NHMRC, but it was considered inferior to the recommended interventions from NICE. BEP received only one conditional recommendation from APA. These three therapies were not selected because they received few or negative recommendations.

Five therapies were selected for the thematic analysis. CPT, CT, and PE, because each received strong recommendations from APA, ISTSS, and NHMRC. EMDR received strong recommendations from NICE, ISTSS, and NHMRC; a standard recommendation from WHO; and a conditional recommendation from APA. NET received conditional recommendations from APA and NHMRC, and a standard recommendation from ISTSS.

Thematic Analysis

CPT, CT, PE, EMDR, and NET were selected for comparison. If all the guidelines are considered, it can be said that CPT, CT, PE, and EMDR have first-level recommendations to treat PTSD in adults, and NET has a second-level one.

During the thematic analysis, similar components of the therapies were identified and grouped into categories: psychoeducation about PTSD; in-session exposure strategies; in-session cognitive strategies; out-of-session strategies; and emotional regulation strategies. Besides these categories, in all therapies, the therapist uses active, nonjudgmental listening to the experience of the patient to form a therapeutic alliance.

Psychoeducatiûn about PTSD

All therapies psychoeducate about PTSD. CPT uses psychoeducation according to the social cognitive theory, focusing on the distorted cognitions that arise when a person seeks to make sense of what happened during a traumatic event (Watkins et al., 2018).

CT uses psychoeducational strategies common to CBT, but with emphasis on the cognitive model of PTSD developed by Ehlers et al. (2000), seeking to reduce the feeling of threat experienced by patients. PE teaches the emotional processing theory, which proposes that fear is represented in cognitive structures in memory and whose repeated activation decreases fear symptoms (McLean & Foa, 2011).

EMDR teaches about PTSD symptoms and their improvement, using the adaptive information processing model (Shapiro, 2007). NET presents the theory of double representation of traumatic memories and postulates that the improvement of the patient occurs through the reorganization of memory in a chronological narrative of positive and negative events in his life story (Schauer, 2015).

In-Session Exposure Strategies

All therapies focus on the traumatic event for resolving PTSD symptoms, with some also focusing on the current difficulties of the patient. According to the manual by Resick et al. (2014), CPT focuses on the traumatic event to identify and record stuck points, which are strongly negative beliefs associated with unpleasant emotions and problematic behaviors. They are addressed using cognitive strategies, and the patient must also try to express emotions while reading written reports about the two most traumatic events.

CT uses imaginal exposure to identify hot spots, traumatic moments that arouse greater stress, and a feeling that they are happening in the present moment. For this, patients must thoroughly describe the event, as if it were currently happening, with associated thoughts and emotions (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). To better contextualize the event, the trauma narrative should begin before the trauma and end when the person is already safe (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Regarding current stimuli that trigger re-experiencing symptoms, they are first identified with the help of the therapist, activated in therapy, and then one can learn to perceive how the present situation differs from the traumatic one (Wild et al., 2020). In addition, problematic cognitive and behavioral strategies that maintain PTSD symptoms in the long term, such as rumination, thought stopping, and safety-seeking behaviors, should be eliminated (Ehlers & Clark, 2000).

PE comprises exposure to anxiogenic stimuli, not requiring the use of relaxation methods to reduce anxiety, although it may use slow and controlled breathing as a relaxation technique (Foa et al., 2009; McLean & Foa, 2011). The exposure occurs in an imaginal and in vivo way, and usually begins hierarchically with the stimulus of less anxiety, but may also begin with the stimulus of greater anxiety (Foa et al., 2009; McLean & Foa, 2011). During the imaginal exposure, patients are asked to visualize the event as vividly as possible and to report it thoroughly in the present tense, describing thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations, while their voices are recorded for daily listening outside the session (McLean & Foa, 2011). A hierarchical list of situations avoided by the patient is made, so they can make in vivo exposure outside the session (McLean & Foa, 2011).

EMDR (Shapiro, 2007) uses exposure by asking the patient to focus on the worst moment of a given trauma while a bilateral stimulation is performed, such as moving the eyes from side to side, listening to bilateral sounds, or with the therapist alternately touching the knees of the patients. Although exposure starts at the worst moment, patients are not required to stay in the traumatic event, their minds usually wander to other moments of the trauma or other memories. At each series of bilateral stimulation, it is checked with them where their mind went, and after consecutive responses of positive experiences, they are asked again to return to the worst moment to verify the emotional intensity. This procedure is also conducted for current and future difficulties.

In NET (APA, 2017b; Schauer, 2015), patients talk chronologically about significant positive and negative events in their lives, with the therapist helping to transform the fragmented traumatic memory into a coherent narrative, contextualizing the experience and maintaining a connection to the here and now. This narrative will then be turned into a written testimony by the therapist, who will read to the survivor, asking for corrections and more details.

In-Session Cognitive Strategies

The comparison of the different therapies allowed this strategy to be divided into two distinct components: challenging and non-challenging cognitive strategies. The challenging ones examine dysfunctional cognitions, seeking to restructure them into more functional ones, whereas in the non-challenging ones the functional cognitions arise through an educational or positive bias.

According to the manual by Resick et al. (2014), CPT teaches patients to identify automatic thoughts and dysfunctional beliefs that are related to traumatic events, challenging and making them change to alternative thoughts that are more adaptive. Besides that, the authors explain that the themes of security, trust, power, control, esteem, and intimacy are addressed to correct current generalized beliefs. They say that this is achieved using Socratic questioning and the following worksheets: A-B-C, challenging questions, challenging beliefs, and patterns of problematic thinking. Regarding the use of non-challenging cognitive strategies, this manual differentiates guilt and responsibility, explaining that, if there is no intention, there is no guilt, that there may be responsibility for an incident, but that the person is not to blame. Furthermore, it also teaches that therapists must help patients remember important parts of a situation, such as that in a war, one must do certain things to survive.

CPT helps patients to identify the meanings of traumatic memories and may use the post-traumatic cognitions inventory to find the main cognitive themes, aiming to help them recognize how these excessively negative evaluations of the trauma or its aftermath exaggerate the current feeling of danger (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Cognitive restructuring of these assessments is conducted using Socratic questioning to help patients to find a new appraisal that is more positive, which will be remembered with the traumatic event so that the new information can be incorporated into the event (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). In addition, patients are encouraged to reclaim their lives by performing activities such as exercising, self-care, hobbies, relationships, and work, something achieved by identifying the initial steps to be taken, as well as problematic beliefs that may hinder patients from progressing (Wild et al., 2020).

According to Ehlers & Clark (2000), the non-challenging cognitive strategy in CT occurs when teaching, for example, that not remembering the trauma is a natural response, it does not mean that there is something wrong with the person. The authors also teach that the pleasurable sexual response during rape is involuntary. It does not mean the person had secret repulsive desires.

PE does not use cognitive strategies, only imaginal and in vivo exposure (APA, 2017c). However, after it, the patient is encouraged to express the thoughts and feelings that arose during the exposure process (Foa et al., 2009).

EMDR (Shapiro, 2007) only uses the non-challenging cognitive strategies. Along with the worst moment of the traumatic experience, patients are asked what negative belief they have about themselves concerning that moment, and also what desired positive belief they would like to have instead of that. After the desensitization phase, when the emotional intensity has already decreased, the person is encouraged to remember the worst moment while thinking about the desired belief. Another cognitive strategy, cognitive interweaving, can be used if there is no change in what is being remembered during desensitization. It comprises asking about some aspect of the traumatic experience or presenting a statement to be considered along with the memory to help patients make new associations and change their thinking.

In NET (Schauer, 2015), only the non-challenging cognitive strategies are used, which occur when the person is reminded that their written account serves as a testimony about the violation of human rights, which can help them regain their dignity and satisfy the need for recognition and validation. In addition, the final document is ritually signed by the witnesses (therapist, interpreter, co-therapist), given to the survivor, and its legal use in human rights work is discussed. Contextualizing the life of the patient, focusing on the positive aspects, may also serve as a cognitive strategy that does not involve the challenge of beliefs, and helps patients to realize that life was not made only by traumatic moments.

Out-of-Session Strategies

The EMDR and NET therapies do not use activities outside of session hours, while the others use different strategies. CPT asks patients to perform various practical tasks at home, such as a stuck points log; a written account of the two most traumatic events, rewriting them in as much detail as possible, and reading the accounts daily with emotional expression if they still feel strong emotional intensity; and to complete the A-B-C, challenging questions, patterns of problematic thinking, and challenging beliefs worksheets (Resick et al., 2014).

In CT, during the sessions, activities are planned to be performed outside of therapy, so that the patient can recover his life, resuming activities and relationships that were interrupted after the trauma (Wild et al., 2020). Patients should also be aware of the cues that trigger re-experiencing symptoms, to train how to discriminate between the present moment and the traumatic situation, as taught in the session (Wild et al., 2020). In addition, strategies such as rumination, thought-stopping, and safety-seeking behaviors should be eliminated in everyday life (Ehlers & Clark, 2000).

In PE, patients are instructed to practice certain activities, like listening daily to the audio recording of the trauma account made during the sessions and practicing the relaxation technique by slow, controlled breathing (McLean & Foa, 2011). Patients are also encouraged to do in vivo exposure, by meeting stimuli that are connected to the trauma, such as specific places or people, which have been selected gradually during therapy so that the patient can cope with the associated emotions (McLean & Foa, 2011).

Emotional Regulation Strategies

CPT, CT, and NET do not use emotion regulation strategies. PE states that it is not mandatory to use relaxation, but that some training can help the patient increase the level of exposure (Foa et al., 2009), such as controlled training in slow breathing (McLean & Foa, 2011).

EMDR uses imaging techniques to help patients if they feel the need to interrupt processing during sessions and to feel better between them (Shapiro, 2007). An example of an imaging technique is to define, with the patient, the image of a safe place so that it can be remembered when necessary (Shapiro, 2007).

Comparative Theoretical Component Analysis of Intervention Strategies

Table 1 shows the intervention strategies identified by thematic analysis. To know the real need for any component belonging to the intervention strategy of a therapy, it would be ideal to develop empirical research comparing the therapy with all of its components to a version of it without the use of a specific component.

Table 1. Intervention strategies identified by thematic analysis in therapies recommended by clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of PTSD in adults.

| Component | Therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT | CT | PE | EMDR | NET | |

| Psychoeducation about PTSD | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| In-session exposure strategies | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| In-session cognitive strategies | |||||

| Challenging cognitive strategies | yes | yes | no | no | no |

| Non-challenging cognitive strategies | yes | yes | no | yes | yes |

| Out-of-session strategies | yes | yes | yes | no | no |

| Emotional regulation strategies | no | no | optional | yes | no |

Note. CPT = cognitive processing therapy. CT = cognitive theory. PE = prolonged exposure therapy. EMDR = eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. NET = narrative exposure therapy.

An example of research with component analysis was the study by Jacobson et al. (1996), on patients with depression, in which one group received only the behavioral activation component (BA); another group received BA and the activation and modification of the dysfunctional automatic thoughts (AT) component; and a third group received the full treatment that included BA, AT, and focus on core beliefs. These authors have concluded that BA alone was as effective as the more complete versions of CBT, even with the participation of therapists with experience in CBT and excellent adherence to the treatment protocol.

Bearing in mind that only empirical research can more robustly prove a certain theoretical proposition, the following discussion shows what could be observed by analyzing recommended therapies for PTSD, based on their components. The use by all therapies, of psychoeducation on PTSD, seems to point to the need for this component for treating PTSD.

However, the use of different theoretical models suggests two possibilities, one supporting its need and one showing that the component is unnecessary. Teaching how patients developed the symptoms and how they can get better may create motivation to stay in therapy despite the intense emotions that arise from remembering the trauma. A second possibility would be that this component is unnecessary, and the patient remains in treatment despite it, possibly because they realize that, as the sessions go by, they are feeling better.

Regarding the trauma exposure component, this seems to be a central aspect of the treatment of PTSD because only two non-trauma-focused therapies received some recommendations. SIT received a conditional recommendation from NHMRC, while APA stated there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against it. PCT received a standard recommendation from ISTSS, a conditional one from NHMRC, and NICE considered it inferior compared to the recommended interventions.

The indication from NICE for the NTF-CBT category, which included SIT, seems to be adequate in providing a partial rationale, explaining that NTF-CBT was only recommended to treat specific symptoms to eventually engage the patient in trauma-focused therapy. Thus, non-trauma-focused therapies may help with symptoms, but it seems that trauma-focused therapy is needed to truly treat PTSD.

Regarding the non-challenging cognitive strategies, this component allows us to broaden the theoretical understanding of EMDR. This happens because the non-challenging cognitive strategy can be understood as evaluative conditioning, a special case of Pavlovian conditioning, while the challenging cognitive strategy is a type of Skinnerian conditioning. This classification goes against a line of understanding that points out that EMDR could be effective because of its cognitive bias.

Besides the individual components, it is important to discuss that, ideally, patients should have access to the best therapy possible to solve their problems. Regarding the first-level ones (CPT, CT, PE, EMDR), are there any that should be preferred over the others? To start with, it is important to have options, as certain people may be better suited to a particular therapy. However, certain factors could point to a preference, such as lower cost, lower treatment dropout rate, shorter duration of treatment, less emotional activation, fewer homework assignments, and easier learning by the therapist.

It appears that no current therapy adequately fits all these criteria. NICE was the only one that analyzed their cost-effectiveness. However, this institution has analyzed CPT, CT, PE, and other therapies belonging to the TF-CBT category, not allowing inferences about them individually. PE seems to use the fewest strategies compared to the other therapies, showing greater ease of learning by the therapist. CPT and CT work more indirectly, by talking about cognitions resulting from the trauma, not using imaginal exposure as much, which may elicit less emotional activation and decrease the dropout rate. EMDR is the only one that does not have homework assignments, and although it uses imaginal exposure, it does not ask the patient to describe the scene thoroughly, in addition, the NICE committee recommended that EMDR be offered as a lower intensity alternative intervention because of the high discontinuation rate of TF-CBT.

Since narrative exposure therapy (NET) has a second-level recommendation, it was analyzed seeking an understanding of this classification. APA (2017a) acknowledged that there is uncertainty about its recommendation and that it may raise its rating in a future analysis. However, the comparison with other therapies seems to show that NET uses a lower level of exposure because no strategies are applied outside of the session, whereas CPT patients fill out worksheets with cognitive analysis and read the written report during the week, CT patients seek to resume interrupted activities and social contacts, and PE patients listen daily to a recording with their narration of the trauma. In addition, challenging cognitive strategies were not used in NET either. Regarding non-challenging cognitive strategies, CPT and CT used them in addition to challenging ones, EMDR used them for each of the high emotional intensity moments processed in session, and NET used them globally, showing only that the report would serve as testimony about the violation of the human rights of the patient.

Thus, NET is an effective therapy that uses exposure and results in improvement in PTSD symptoms, but it may not become as effective as other therapies because it has a lower level of exposure. On the other hand, if empirical research brings the recommendation of NET to the first level, then it could be used as the first option among the others, since it does not need as much exposure and it does not require as many different strategies from the therapist.

Regarding short exposure time, EMDR stands out for not having homework and not demanding detailed description of the event, exposing patients to fewer stimuli related to the traumatic event. However, unlike NET, EMDR uses non-challenging cognitive strategies in processing all traumatic scenes.

A unique feature of EMDR consists of using bilateral movements while remembering the traumatic event. Although its necessity is debatable, it can be explained according to a behavioral principle pointed out by Guimarães (2019), who presented empirical research to support the idea that the addition of external stimuli can facilitate, inhibit, or not influence the extinction process of a conditioned stimulus.

In EMDR, bilateral movements would function as the external stimulus, and the author points out that the variable that determines the obtained result is the ability of the external stimulus to distract attention from the conditioned stimulus during the extinction process, with mild distractions causing the external stimulus not to influence the results, strong distractions causing the extinction to take longer or not occur, and moderate distractions facilitating the extinction process, making it more effective than the usual extinction process. Also, according to the author, this principle would be the same used in the therapy called emotional freedom technique, which was the only therapy that received a research recommendation by NICE because of its large effect size and cost-effectiveness, but low amount of evidence.

CONCLUSION

This study aimed to compare the intervention strategies of therapies to treat PTSD that have been recommended by clinical practice guidelines. This aim was specifically achieved, first, by performing a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines to treat PTSD in the last 10 years, which returned 1,523 studies from which five guidelines were selected.

Then, the second specific aim was achieved by selecting the most recommended individual therapies according to these five guidelines. When all guidelines are considered, it can be said that cognitive processing therapy (CPT), cognitive therapy (CT), prolonged exposure therapy (PE), and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) have a first-level recommendation and narrative exposure therapy (NET) has a second-level one for treating PTSD in adults.

However, the use of categories in the guidelines, rather than just specific therapies, was surprising. The category trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) mixed treatments from different recommendations, which could give the idea that a particular treatment was effective just by belonging to this category with no individual analysis. This can be seen in the nine treatments that make up this category in the ISTSS analysis, where the category received a strong recommendation, but in the individual analysis, only three (CT, CPT, NET) had strong recommendations for treating PTSD.

Similarly, the category cognitive-behavioral therapy without a trauma focus (NTF-CBT) in the ISTSS guideline was said to be effective for trauma, but when NHMRC expanded the ISTSS analysis and removed stress inoculation training (SIT) it, it was clear that NTF-CBT was not recommended for PTSD, only SIT was. Another important point is that NICE recommends NTF-CBT, which again may give the impression that it is effective for PTSD, however, a more careful analysis of the guideline shows it is only recommended for specific trauma symptoms, to later engage the patient in trauma-focused therapy.

APA has used an even broader category that included both TF-CBT and NTF-CBT in CBT. However, the difference in the strength of recommendation from other institutions (WHO, NICE, ISTSS, and NHMRC) suggests that the distinction between these two subcategories is important. Among individual therapies belonging to TF-CBT only CPT, CT, and PE received strong recommendations according to ISTSS, NHMRC, and APA; and in NTF-CBT, only individual SIT received one conditional recommendation from NHMRC, and APA considered the evidence insufficient to recommend for or against it. Since APA has individually analyzed CPT, CT, PE, and SIT, it is difficult to understand the purpose this institution had in creating the CBT category and stating that it is strongly recommended for PTSD, as this confuses those reviewing the guidelines by giving the impression that NTF-CBT is strongly recommended, and that some therapy claiming to be TF-CBT, other than CPT, CT, and PE, is also strongly recommended, which does not seem to be the case according to the other guidelines analyzed.

Once the recommended therapies were identified, the last specific objective was achieved by identifying the intervention strategies of each therapy and comparing them. The strategies were grouped into categories because of similarities, which allowed them to be discussed more easily. It was observed that all recommended therapies make use of exposure to the traumatic situation to be effective in reducing PTSD symptoms, although varying how this occurs.

This systematic review has allowed the identification of the recommended therapies for PTSD and the thematic analysis of the intervention strategies of these therapies allowed the classification of their components into certain categories. It is expected that these data can facilitate the choice of components to be removed in future empirical component analysis research, that seeks to pinpoint what is essential to treat this disorder. It is also expected that these data may guide the choice of components that can be added to increase the effectiveness of a therapy, such as allowing NET to move from the second to the first level of recommendation. Another possibility is that a more in-depth study of the five recommended therapies would allow for the development of a unified theoretical framework.

The present study has limitations, such as the risks of bias pointed out in the methodology, one of which is due to the fact that guidelines in German, Dutch, Finnish and Hebrew were found but not analyzed. Furthermore, there is a possibility that different authors may identify different categories according to the thematic analysis.