Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Terapias Cognitivas

versão impressa ISSN 1808-5687versão On-line ISSN 1982-3746

Rev. bras.ter. cogn. vol.19 no.spe1 Rio de Janeiro 2023 Epub 15-Jul-2024

https://doi.org/10.5935/1808-5687.20230043-en

Review article

Schema mode inventory in cases of aggressive behavior: A systematic review

1Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande Do Sul - PORTO ALEGRE - Rio Grande do Sul - Brazil

2Universidade Federal Da Grande Dourados - Dourados - MS - Brazil

3Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande Do Sul - PORTO ALEGRE - Rio Grande do Sul - Brazil

The present study, a systematic review covering the analysis of publications in Portuguese and English from 2010 onwards, aims to survey empirical research using the Schema Mode Inventory (SMI) in cases of aggressive behavior. Using the acronym PICOS, the following question arises: What are the benefits (O), proven in empirical studies (S), of using the SMI (I) in work with adults with aggressive behavior (P)? The search was carried out in the databases PePSIC, Lilacs, PubMed, SciELO, PsycINFO, and SCOPUS, from which we selected nine articles. We noticed a low rate of publications, mainly in Brazil, and a greater focus on the correlation between schema modes and personality disorders, leaving a low number of publications on other topics. The results point to the possibility of using the SMI as a tool within a therapeutic process and as an assessment tool. The schema modes most related to aggressive behavior were the Impulsive Child, Angry Child, and Bully-andAttack. Due to the limitations found, mainly related to sample homogeneity and risk of bias in self-report instruments, further studies are necessary to elucidate the possibilities and benefits of using SMI in interventions with aggressive individuals.

Keywords: Aggression; Schema Therapy; violence

O presente estudo visa o levantamento de pesquisas empíricas com a utilização do Schema Mode Inventory (SMI) em casos atrelados a comportamento agressivo. Trata-se de uma revisão sistemática abarcando a análise de publicações nos idiomas português e inglês a partir do ano de 2010. A partir do acrônimo PICOS, foi designada a pergunta: Quais os benefícios (O), comprovados em estudos empíricos (S), da utilização do SMI (I) no trabalho com adultos com comportamento agressivo(P)? A busca foi realizada nas bases de dados PePSIC, Lilacs, PubMed, SciELO, PsycINFO e SCOPUS, e, ao final, apenas 9 artigos foram incluídos. Percebeu-se um baixo índice de publicações, principalmente no Brasil, e um enfoque maior na correlação entre modos esquemáticos e transtornos da personalidade, restando um baixo número de publicações com outros temas. Os resultados apontam para a possibilidade de utilização do SMI como ferramenta dentro de um processo terapêutico e como instrumento de avaliação. Os modos esquemáticos mais relacionados ao comportamento agressivo foram: Modos Criança Impulsiva, Criança Raivosa e Bully-and-attack. Devido às limitações encontradas, principalmente relacionadas a homogeneidade de amostra e risco de viés dos instrumentos de autorrelato, fazem-se necessários novos estudos que elucidem possibilidades e benefícios da utilização do SMI nas intervenções com indivíduos agressivos.

Palavras-chave: Agressão; Terapia do esquema; Violência

INTRODUCTION

Schema therapy (ST) is a relatively new, integrative approach that expands traditional cognitive-behavioral treatments and concepts (Salicru, 2023; Young et al., 2009). It integrates elements from different approaches, such as Gestalt therapy, attachment theory, and psychodynamic understanding (Koppers et al., 2021), and uses mental imagery techniques that stimulate a greater connection with emotions (Fiuza & de Godoy, 2021; Keulen-de Vos et al., 2017). ST has developed over the last two decades as a medium to long-term treatment (Oleśniewicz, 2021), with a high level of evidence of effectiveness for personality disorder cases (Zhang et al., 2023). It greatly emphasizes the developmental aspects of patients’ symptoms and problems (Fassbinder et al., 2019; Oettingen & Rajtar-Zembaty, 2022).

Among the main concepts of the ST are early maladaptive schemas (EMSs) and schema modes (Young et al., 2009). EMSs are like cognitive structures formed by memories, bodily sensations, and emotions related to the view of the self and the relationship with others (Bach & Farrel, 2018; Dunne et al., 2018; Keulen-de Vos et al., 2017; Westphalen & Méa, 2018). They develop from the interaction of the genetic basis of temperament with the basic needs to be met by caregivers in childhood, also associated with the experiences of repeated and/or traumatic experiences (Bach & Farrel, 2018; Baldissera et al., 2021).

The schema modes encompass several EMSs and active coping modes simultaneously (Clercx et al., 2021; Dunne et al., 2019; Matos et al., 2018) and can be differentiated from EMSs by the issue of stability and constancy (Matos et al., 2018). EMSs develop early, last throughout life, and tend to recur in different situations (Flanagan et al., 2023; Soygüt et al., 2023). On the other hand, schema modes represent an individual’s dissociated “state” at a given moment and can be both adaptive and maladaptive (Matos et al., 2018).

Schema modes generate oscillations in individuals’ emotional and cognitive states and their behavioral tendencies (Bach & Farrel, 2018; Damasceno et al., 2019). Ten basic schema modes are divided into four broad categories: Innate Child Modes, Maladaptive Parent Modes, Maladaptive Coping Modes, and the Healthy Adult Mode (Bachrach & Arntz, 2021; Young et al., 2009). The ten schematic modes are briefly described in Table 1.

Table 1 Schema modes description (including the ten original ones and the four included in the elaboration of the SMI).

| Original Schema Modes | |

|---|---|

| Schema Modes | Description |

| Vulnerable Child | Experiences dysphoric or anxious feelings, especially fear, sadness, and helplessness, when “in contact” with associated schemas. |

| Angry child | Releases anger directly in response to unmet fundamental needs or unfair treatment related to nuclear schemas. |

| Impulsive child | Acts impulsively, according to immediate desires for pleasure, without considering limits or the needs or feelings of other people. |

| Happy child | Feels loved, connected, content, satisfied. |

| Compliant Surrender | Adopts a coping style based on obedience and dependence. |

| Detached Protector | Adopts a coping style of emotional withdrawal, disconnection, isolation, and behavioral avoidance. |

| Hypercompensator | Adopts a coping style characterized by counterattack and control. May overcompensate through semiadaptive means such as overwork. |

| Punitive/critical parent | Restricts, criticizes or punishes themselves or others. |

| Demanding parent | Establishes high expectations and levels of responsibility towards others; pressures themselves or others to comply. |

| Healthy adult | It is the healthy and adult part of the self that fulfills an “executive” function regarding other modes. It helps to satisfy the child's basic emotional needs. |

| Schema modes included in the elaboration of the SMI | |

| Undisciplined child | Unable to force themselves to perform tasks considered boring; gets easily frustrated and gives up easily. |

| Enraged child | Experiences strong feelings and hurts people or damages objects. Anger gets out of control and the goal is to destroy an aggressor. Experiences the consequences of an out-of-control angry child, acting impulsively against a perceived aggressor. |

| Detached self-soother | Repeatedly uses addictions or obsessive behaviors or self-stimulating behaviors to calm and gratify themselves. Uses pleasant and stimulating sensations to distance themselves from unpleasant feelings. |

| Bully-andattack | Offends, controls, deceives, or acts in a passive-aggressive manner to deal with abuse, distrust, deprivation, and deficiencies, and get what they want. Takes sadistic pleasure in attacking other people, |

Note: Adapted from Young et al. (2009) and Bär et al. (2023).

The schema mode inventory (SMI) is used to measure the activation of these schema modes (Damasceno et al., 2019). It has two versions: the original version, with 270 items, and the short version (SMI-R), derived from the original version, with 118 items. The latter is subdivided into 14 subscales, and its items are evaluated through a Likert scale of six points, ranging from “never or almost never” to “always” (Barazandeh et al., 2018; Lobbestael et al., 2010). The reduced version of the SMI (SMI-R) was proposed in 2010 by Lobbestael et al. (Matos et al., 2020). In its formulation, four modes were added to the ten initially proposed by Young et al. in 2009: Undisciplined Child, Enraged Child, Detached Self-Soother, and Bully-and-Attack (Matos et al., 2020), as described in Table 1.

Through psychoeducation, working with schema modes helps us understand the origin of the modes, their functioning and their triggering situations (Dunne et al., 2018; Maffini et al., 2020). The objective of the ST is to reduce the intensity and frequency of oscillation of schema modes, allowing the most adaptive ones to predominate in the patient’s life (Soygüt et al., 2023).

Interventions that advocate working with schema modes have been recommended for more challenging personality disorders, such as antisocial, narcissistic, borderline, or paranoid cases (Oleśniewicz, 2021). These clinical conditions present high recurrence levels, which justifies its indication (Bernstein et al., 2023).

Understanding the schema modes can be relevant for understanding criminal and violent behaviors (Bernstein & Navot, 2023) since, according to the ST, acts of violence are defined as emotional states of anger and hypercompensatory strategies involving threat, intimidation, and aggression (Vos et al., 2023). In these cases, patients easily understand the work from the perspective of schema modes. They use them intuitively as a self-intervention, which allows the therapist to monitor their patients better and choose the most appropriate therapeutic tools (Oleśniewicz, 2021).

Challenging or criminal behaviors originate from a sequence of developments of maladaptive schema modes (Bernstein et al., 2023; de Klerk et al., 2022). Such a sequence typically begins with schema modes related to vulnerability, abandonment, and loneliness (Vos et al., 2023), intensifies from modes involving impulsivity, anger, and substance abuse, culminating in modes related to reactive or predatory aggression (Bernstein & Navot, 2023).

ST was adapted for the forensic population (Bernstein & Navot, 2023) and in 2007, researchers identified five typical hypercompensating schema modes in the forensic population: Self-Aggrandizer, Bully-and-Attack, Predator, Conning Manipulator, and Paranoid Overcontroller, whose descriptions are shown in Table 2 (Bernstein et al., 2007; Soygüt et al., 2023). “Forensic schema modes” increase the likelihood of offending and aggressive behaviors, as they typically represent maladaptive attempts to deal with painful and unwanted feelings (Oettingen & Rajtar-Zembaty, 2022).

Table 2 Description of schema modes common in the forensic population.

| Schema Modes | Description |

|---|---|

| Self-aggrandizer | Attempts to dominate or control, impose their will on other people. Acts as if they were the boss, the alpha male or female who is in charge and control of everyone and always gets what they want. |

| Bully-andattack | Threatens and intimidates, makes explicit threats to harm other people, or intimidates by saying they will do so, and uses intimidating gestures and body language to get what they want. |

| Conning manipulator | Plays a role to get something they want indirectly, has a secret intention or double life, uses charm and manipulation to achieve instrumental ends, lies with ease and softness, treats the truth as fungible. |

| Paranoid Hypercontroller | Always on high alert for harm or threats, they sit with their back to the wall to scan the room and investigate for problems, constantly looking for small signs that others are conspiring against them. The ultimate assumption is that no one can be trusted. |

| Predator | Can hurt, kill or destroy to achieve an instrumental end or for revenge. Is indifferent to the damage or suffering they cause, sees things as “just business”. Can plan predatory acts weeks or months in advance, preparing them in secret and carrying them out coldly and methodically. |

Note: Retrieved from Bernstein and Navot, 2023, p. 210-211.

Although there have been studies on ST for many years, the number of publications achieved in this systematic review highlights the precariousness of the number of empirical studies on schema modes. Considering that “forensic schema modes” also appear in non-forensic environments, the existing bibliography on the use of SMI in cases of aggressive behavior is relevant not only for research purposes but also to assist clinical therapists who may face major problems because they do not know how to recognize or intervene with these modes (Bernstein & Navot, 2023). Such ignorance can also create obstacles to the therapeutic relationship, considered a primary agent of change in ST (Salicru, 2023).

This systematic review aims to encompass studies in which behaviors described as aggressive or violent have a motivation and/or repercussions related to the definition of violence decreed by the World Health Organization (Dahlberg & Krug, 2006):

The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, mal-development or deprivation.

The definition used by the WHO associates intentionality with the completion of the act, regardless of the result produced (p. 279).

Therefore, the correlation between the themes “schema modes” and “aggressiveness/violence” constitutes a topic of great relevance since individuals with aggressive behavior represent a risk to themselves and/or society. We will seek to identify how the data obtained from the SMI proved helpful for understanding aggressive behavior or in interventions with violent individuals and its contributions to understanding and treatment of this population, usually segregated and stigmatized as incurable.

METHOD

The design of this study involves a systematic review of the literature. The guiding question was created based on the PICOS strategy, an acronym considered very useful for formulating questions (Fuchs & Paim, 2010), as described in Table 3. Therefore, the following research question arises: “What are the benefits, proven in empirical studies, of using SMI in working with adults with aggressive behavior?”

Table 3 PICOS acronym for formulating the guiding question of the systematic review.

| Acronym | Definition | Application of the criterion in the present study |

|---|---|---|

| P | Population | Adults with aggressive behaviors |

| I | Intervention | Using SMI |

| c | Comparison indicator | In this study there is no comparison indicator |

| 0 | Outcome | Benefits |

| s | Type of study | Empirical Studies |

Note: PICOS = Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design.

After determining this guiding question, we selected descriptors previously validated on the platform Health Sciences Subject Descriptors (Descritores de Assunto em Ciências da Saúde - DECS) and keywords related to the components of the PICOS strategy to be used in search strategies. For this purpose, works from the PePSIC, Lilacs, PubMed, SciELO, PsycINFO and SCOPUS databases were considered. No grey literature was included.

The descriptors “terapia do esquema”, “violência”, “agressão” and “raiva”, and their English versions “schema therapy”, “violence”, “aggression” e “anger” were used. The follow ing keyword was also used in Portuguese and English: “modos esquemáticos” and “schema modes”. All the terms mentioned above were connected by the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND”, and the final search strategies are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Final database search strategy.

| Databases | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| Pepsic Lilacs |

"Schema Therapy" OR "Schema modes" [All indices] AND Aggression OR Violence OR Anger [All indices] (("schema modes" OR "schema therapy") AND (aggression OR violence OR anger)) |

| PubMed | (("schema therapy"[Title/Abstract] OR "schema modes"[Title/Abstract]) AND (aggression [Title/Abstract] OR anger [Title/ Abstract] OR violence [Title/Abstract])) |

| Scielo | (("Schema therapy" OR "Schema modes") AND (agression OR violence OR anger)) |

| PsycINFO | ((Any field: "schema therapy" OR Any field: "schema modes") AND (Any field: aggression OR Any field: violence OR Any field: anger)) AND Peer-Reviewed Journals only (Title-Abs-Key ("schema therapy") OR (Title-Abs-Key ("schema modes") AND (Title-Abs-Key (aggression) OR (Title-Abs-Key |

| Scopus | (violence) OR (Title-Abs -Key (anger)) AND Pubyear > 2009 AND (Limit-to (SUBJAREA, "PSYC")) AND (Limit-to (DOCTYPE, "ar")) AND (Limit-to (LANGUAGE, "English") OR Limit -to (LANGUAGE, "Portuguese")) |

We selected studies published from 2010 onwards because this was the year the SMI was prepared in Portuguese and English. The searches and selection were carried out by two reviewers (JP and FS) independently, and if they disagreed, an independent reviewer (KS) was consulted to discuss consensus.

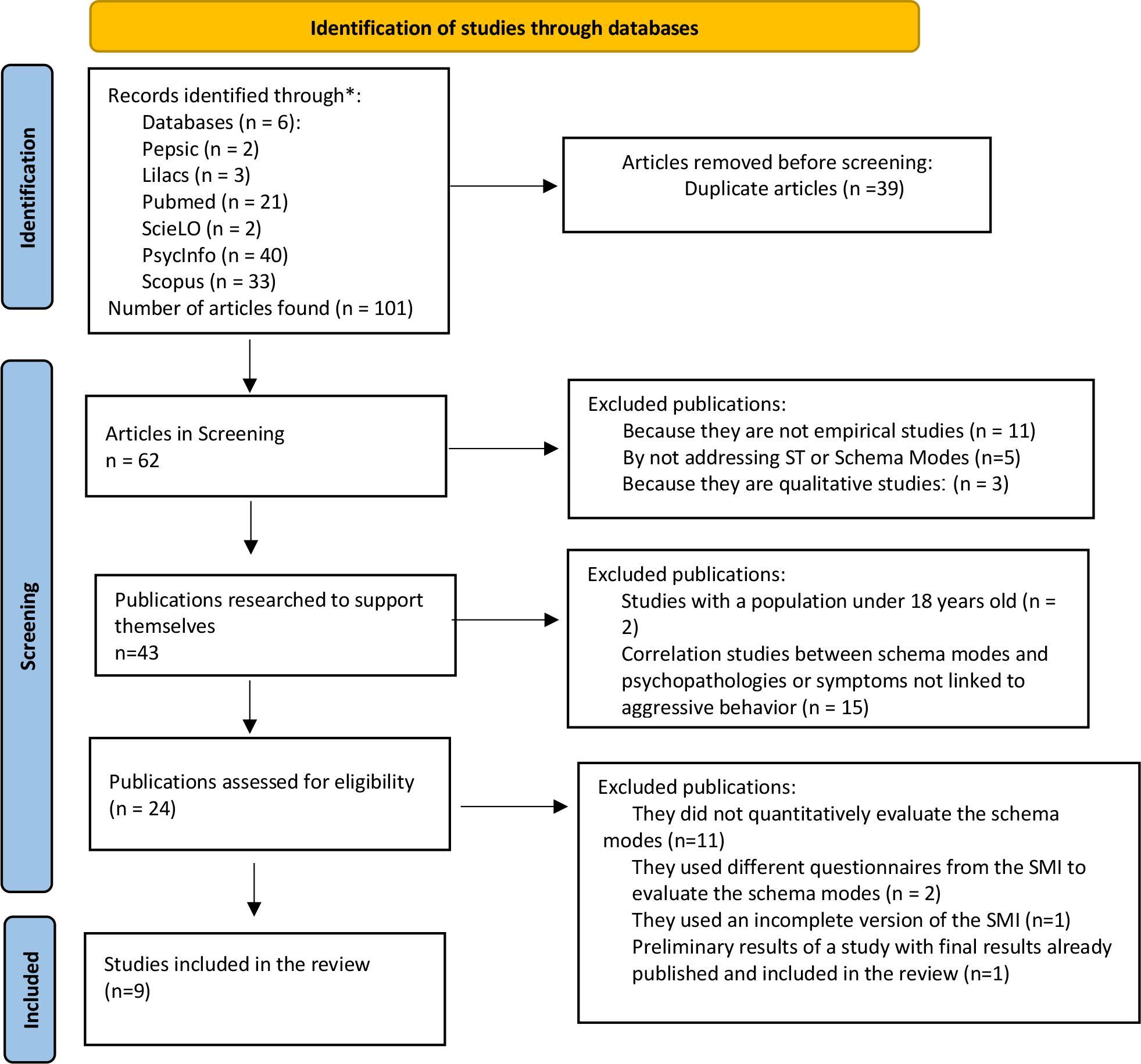

One hundred two studies were selected in this preliminary phase. After eliminating 39 duplicates, 63 studies were chosen for the abstract reading phase. The inclusion criteria were being an empirical and quantitative study and addressing the ST theme or schema modes. Forty-four articles were then selected for a second screening.

In the second screening, studies with a population under 18 years of age were excluded, as well as studies that correlated schema modes and psychopathologies or symptoms not linked to aggressive behaviors. Studies whose method was a case study were also excluded (due to their low level of scientific evidence).

The remaining studies were read in full, and the inclusion criteria established were the application of the schema modes inventory (SMI) and the concept of aggressive behavior consistent with that specified by the authors. From this, texts that fit the research theme were selected, resulting in nine studies. The study selection flow is detailed in Figure 1.

Note: Translated by: José Luís Sousa*, Sónia Gonçalves-Lopes*, Verónica Abreu*, and Verónica Oliveira / *ESS Jean Piaget - Vila Nova de Gaia - Portugal by: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Figure 1 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for systematic reviews.

The risk of bias in the randomized clinical trial (RCT) included in the final selection was carried out through the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist, and the risk of bias in cross-sectional studies was assessed using the instrument ROBUST - Risk of bias used for surveys tool, an accessible and flexible instrument designed to evaluate the risk of bias in survey studies (Nudelman & Otto; 2020). Analyses were performed independently by two reviewers (JP and FS), and a third reviewer was consulted (KS) in cases of disagreement.

RESULTS

The results prove the need for more studies on this topic and uniformity in descriptors and keywords related to the subject. Upon consultation of the descriptors by DECS, we found no descriptors related to schema modes. The only descriptor linked to the issue is schema therapy (and its Portuguese version), a term that results in an extensive database search.

Furthermore, the searches were first carried out in October 2022 and redone in August 2023. No articles were found in any of the selected databases that fit the theme of this systematic review in Portuguese. Therefore, the term “inventário de modos esquemáticos” [schema modes inventory] was not helpful when used as a keyword for searches.

Aiming to identify the types of national research being carried out with the schema modes inventory, we used the term as the only keyword without refining the searches according to the inclusion criteria for this study in the databases selected for this review. However, this search yielded no results. This fact corroborates the idea that there is no uniformity in descriptors and keywords related to schema modes, as there are bibliographic reviews and other types of studies on schema modes inventory carried out in Brazil.

After that, we searched its translation into English, “schema mode inventory” (SMI), or just “schema modes”, and yet obtained no results from the SciELO database. On the other hand, in this same database, from the descriptor “schema therapy,” we could locate six studies published in the last five years, only one related to schema modes. However, although this is an empirical study using the SMI, it needed to meet the inclusion criteria of this systematic review as it is a case study.

For the term “schema modes” and the descriptors “schema therapy,” “aggression,” “violence,” and “anger,” connected by Boolean operators “OR” and “AND,” the PubMed platform tracked articles that, when refined, resulted in 16 studies published in the last five years, including four empirical studies on the theme of aggression/violence. Using the same search criteria in the PePSIC database, we found two studies, both from literature reviews (therefore, excluded from this systematic review). In the Lilacs database, accessed through the VHL Regional Portal, we could locate six studies, of which only one involved the topic schema modes but did not fit the inclusion criteria of this study.

The databases that allowed access to more studies were SCOPUS and PsycINFO. With the descriptor “schema therapy,” the keywords “schema modes,” “aggression,” and “violence” connected by Boolean operators “OR” and “AND,” we tracked 46 articles. Among the 15 articles located in Scopus, four met the inclusion criteria proposed here, while among the 31 articles found in PsycINFO, five were also in accordance with the proposal of this systematic review. This information is described in the flowchart shown in Figure 1.

An assessment of the level of evidence of the studies was carried out, considering the following factors: sample characteristics, type of sample recruitment, exclusion criteria, final sample size, explanation of the sociodemographic data of the sample, reliability measures of the instruments, location of the study, and method of data analysis. All these aspects were evaluated by two judges separately. The proportion of agreement between the articles’ clarity criteria was 0.89 (or 89.0%), and the kappa agreement index was equal to 0.420 (95%CI: 0.014, 0.825), with moderate strength. These values are detailed according to aspects covered and presented in Table 5. Similarity was observed in the agreements for most of the evaluation items of each article.

Table 5 Kappa index of agreement and 95%CI according to aspects covered.

| Kappa coefficient | Standard ERROR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|

| 0.420 | 0.207 | (0.014, 0.825) |

The results prove that the theme chosen for this review represents a critical area of psychology that requires additional investigations, especially in Brazil, which is evident because none of the selected empirical studies were done in Brazil, and all articles are in English.

As for bibliometric indicators, the following items were broken down: authors, year of publication, journal of publication with impact factor, country, and keywords that made it possible to locate the article in this systematic review. The main details on the sample content and bibliometric indicators are shown in Tables 6 and 7. As shown in Table 6, we can identify that the constituted study material presents the theme of using the inventory in schematic ways under different approaches. As shown in Table 7, each study was published in a different publication vehicle.

Table 6 Description of sample content.

| Article | Objective | Data and Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Study 1 Schema Therapy for Violent PD Offenders: A Randomized Clinical Trial (Bernstein et al., 2021). |

Conduct a randomized clinical trial to test the effectiveness of long-term psychotherapy in the rehabilitation of criminal offenders with personality disorders. |

The authors compared the schema therapy (ST) versus the treatment-as-usual (TAU) in eight high-security psychiatric hospitals in the Netherlands. One hundred and thirty male offenders with antisocial, narcissistic, borderline, or paranoid personality disorders, or Cluster B personality disorders, received three years of ST or TAU and were reassessed every six months. Patients in both conditions received multiple treatment modalities and differed only in the specific and individual therapy they received. Several instruments were used to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments, including the SMI. |

Patients in both conditions showed moderate to great improvement results. The ST achieved better results than TAU in both primary outcomes regarding rehabilitation and symptoms of personality disorders. In secondary results, ST obtained superior results in six of the nine treatment objectives outlined, presenting advantages over TAU. |

|

Study 2 Extending the General Aggression Model: Contributions of DSM-5 Maladaptive Personality Facets and Schema Modes (Dunne, Lee & Daffern, 2019). |

The research sought to determine whether adding DSM-5 personality traits and schema modes improved the prediction of aggression history compared to the cognitive knowledge and anger of GAM (general aggression model) structures. |

The research participants were 208 adult male inmates of a maximum security prison in Australia, aged between 18 and 60. They completed a battery of self-report psychological tests assessing the constructs and structures mentioned in the objective of the work. The DSM-5 hostility and risk propensity traits and schema modes were evaluated. |

The results indicated that cognitive knowledge structures related to aggression, anger, various personality traits, and schema modes were significantly associated with aggression, especially the Impulsive Child, Enraged Child, and Bully-andAttack. |

|

Study 3 Healthy Emotions, Lower Risk? The Relationship Between Emotional States and Violence Risk Among Offenders with Cluster B Personality Disorders (Clercx, Keulen-de Vos & Beuerskens, 2021). |

The study sought to find a relationship between schema modes and the risk of violence. It examines the relationship between healthy and unhealthy emotional states and the risk of violence and whether changes in the risk of violence can be predicted by changes in emotional states. |

This study is part of Study 1. N= 103 male criminal offenders in psychiatric hospitals in the Netherlands, with Cluster B personality disorders or Cluster B not otherwise specified (NOS), and high risk of relapse into violent conduct. The researchers used SMI to examine healthy and maladaptive emotional states and the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START) to assess the short-term risk of violence and to monitor these changes. Followup was assessed after six, twelve, and eighteen months. |

The results showed that all models are important, but neither healthy nor maladaptive emotional states nor the passage of time were significant predictors of the risk of violence. An exception was noted at six and 12 months of the START efforts, where a healthy schema mode inventory result was a relevant predictor in the model. |

|

Study 4 The Role of Aggression-Related Early Maladaptive Schemas and Schema Modes in Aggression in a Prisoner Sample (Dunne et al., 2018). |

The study examined associations between early maladaptive schemas (EMSs), schema modes, and aggression in a sample of offenders. |

This study is part of a larger study by the same researchers (such as study 2), carried out in Australia. Sample: 208 adult male inmates aged between 18 and 60. They completed psychological self- assessments that measured their aggression histories, EMSs, and schema modes. |

Regression analyses revealed that EMSs were significantly associated with aggression but did not account for the portion of variance when the effects of the schema modes were related. The schema modes enraged child, impulsive child and bully-and-attack schema modes predicted aggression |

|

Study 5 Assessing Schema Modes Using Self and Observer Rated Instruments: Association with Aggression (Lewis et al., 2021). |

The study aims to examine the association between SMI instruments and MOS (Mode Observation Scale), and identify their correlations with the identification of schema modes related to aggression. |

The research participants were 59 male patients, between 23 and 73 years old, admitted to psychiatric hospitals in Australia. To evaluate the schema modes, the SMI and MOS, self-report observer-report tools used by patients and nurses who reported on the participants' behavior in the last two weeks. In addition, recordings of aggressive behaviors that occurred in the month following participants' completion of the SMI were analyzed. |

MOS and SMI do not assess schema modes equally. The Vulnerable Child and Lonely Child modes commonly precede aggressive episodes, while the Impulsive Child, Angry Child and “Bully-and-Attack” were present in self-reports of aggressive behavior. The Angry Child, Impulsive Child, and “Bullyand-Attack” are correlated with aggression. |

|

Study 6 Validation of the Schema Mode Concept in Personality Disordered Offenders (Keulen De-Vos et al., 2017). |

In this study, three aspects of the validity of schema modes were tested in offenders with Cluster B personality disorders, and the relationships between personality disorders and the risk of violence. |

The research sample comprised 70 offenders with antisocial, borderline, and narcissistic personality disorders. Schema modes were assessed with the SMI, personality disorders with the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality-Forensic Version (SNAP-FV), and the risk of violence with Historical, Clinical and Risk management (HCR-20v2). |

The hypotheses of this research were partially supported. Additionally, the Angry Child, Impulsive Child, and Bully-and- Attack were associated with anger, impulsivity, self-aggrandizement and hypercompensation, and were relevant predictors for the risk of violence within the hospital. |

|

Study 7 Dysfunctional Parenting and Psychological Symptomatology: An Examination of the Mediator Roles of Anger Representations in the context of the Schema Therapy Model (Gülüm & Soygüt, 2022). |

This study investigates the mediating roles of anger-related schema modes in the relationship between dysfunctional parenting and psychological symptoms. |

The research focused on specific schema modes: punitive and demanding parent modes; vulnerable, angry and enraged child modes; and angry protective mode. The study included 297 university students (159 women) with an average age of 19.66. All participants completed self-report questionnaires on schema modes and psychological symptoms. Two different mediational models were evaluated to understand two different styles of dysfunctional parenting (punitive parent mode and demanding parent mode) and their correlations with the other modes mentioned above. |

The vulnerable child, angry child, and enraged child modes mediate the punitive parenting mode and psychological symptoms and also mediate the demanding parent mode and psychological symptoms. The demanding parent modes are directly related to the enraged child and angry protective modes and partially associated with psychological symptoms. The research corroborates previous studies that indicate that the schema modes related to anger are a way of covering up the vulnerable child mode, and are closely related to the punitive parent mode. |

|

Study 8 Schemas and Modes in Borderline Personality Disorder: The mistrustful, shameful, angry, impulsive, and unhappy child (Bach & Farrel, 2018). |

This study investigated how initial maladaptive schemas (EMSs) and schema modes uniquely characterize patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) versus other comparison groups. |

The sample analyzed was based on data from patients with BPD (n=101), patients without BPD but with some other personality disorder (n=101), and healthy people in the control group (n=101). Differences were investigated through one-way ANOVA and multinomial logistic regression analysis. |

The results indicated that the Vulnerable Child, Happy Child (low), Impulsive Child, Angry Child, and Enraged Child modes uniquely differentiated patients with BPD from patients in the other two groups. According to the authors, such predominance of schema modes reflects the tendency to anger and explosive behaviors, following DSM-V diagnostic criteria. |

|

Study 9 Relationships between early maladaptive schemas and emotional states in individuals with sexual convictions (Vos et al., 2023). |

Assess EMSs and emotional states in individuals convicted of sexual crimes, comparing them to those convicted of other types of violence. |

The Schema Questionnaire and the SMI were applied to 95 patients from two maximum security hospitals (N=30 convicted of sexual violence against children, N=34 convicted of sexual violence against adults, N=35 convicted of crimes of other natures). |

No significant differences were found between the three groups. All had the same incidence of EMSs related to hypervigilance and impaired autonomy and performance. They also showed a similar incidence of modes related to child, avoidant, and hypercompensatory modes. |

Table 7 Bibliometric indicators.

| Article | Journal | Impact factor | Year of publication | Country | Descriptors and keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Psychological Medi cine. | 10.592 | 2021 | The Netherlands | Schema Therapy, Violence, Aggression. |

| Study 2 | Psychology, Crime and Law. | 2.0190 | 2019 | Australia | Schema Modes, Aggression, Anger. |

| Study 3 | Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice. |

0.9050 | 2021 | The Netherlands | Schema Mode Inventory, Violence. |

| Study 4 | Aggressive Behavior | 3.047 | 2018 | Australia | Schema Modes, Aggression |

| Study 5 | Journal of Interpersonal Violence. |

2.621 | 2021 | Australia | Schema Modes, Aggression |

| Study 6 | Legal and Criminological Psychology |

1.756 | 2017 | The Netherlands | Schema Mode Inventory, Violence. |

| Study 7 | Psychological Reports. | 1.789 | 2022 | Turkey | Schema Modes, Schema Therapy, Anger. |

| Study 8 | Psychiatry Research. | 11.225 | 2018 | Denmark | Schema Mode Inventory, Anger. |

| Study 9 | Sexual Abuse | 2,3 | 2023 | The Netherlands | early maladaptive schemas, violent offending. |

The years of publications confirm that the topic addressed here is recent in scientific circles worldwide. Only two studies have been published, one in 2023 and another in 2022. However, the latter is slightly older, first published in 2020 and republished in 2022.

The sample content of this systematic review is composed of articles published in scientific journals with different impact factors, even in the case of papers that were part of the same study. The study published in the journal with the lowest impact factor (Study 3) is part of another more robust study (Study 1), which, in turn, was published in the journal with the second-highest impact factor in the sample. Study 2 (Dunne et al., 2019) was based on results from Study 4, conducted by the same researcher and other collaborators in 2018.

The countries responsible for most studies found are Australia and the Netherlands. The other two countries responsible for the research that supports this review are Turkey and Denmark, with an investigation being carried out in each country. The latter is the country that publishes the highest impact scientific journal in the sample.

Considering that ST scientific contributions are commonly associated with personality disorders, four of the nine studies in this systematic review also address this topic (Studies 1, 3, 6, and 8). In almost all studies, the sample comprised male offenders. Of the nine studies analyzed, four were conducted in prison units and three in forensic psychiatric hospitals. The studies whose participants did not fit into the forensic population were Gülüm and Soygüt’s (2022) and Bach and Farrel’s (2018).

These two studies above involved participants of both genders, not being restricted to males as in other cases. Gülüm and Soygüt (2022) claim to have tested, through an ANOVA analysis, whether there would be signs of significant differences related to gender in terms of the variables tested. The results proved that gender differences were not important in this study.

In all cases, the SMI was used as a complementary instrument within an evaluation process composed of qualitative and quantitative instruments, depending on each research’s objective. Only two of the eight studies used the SMI as an assessment instrument within a psychotherapy process in ST, with the two studies being correlated, as they are part of the same research.

Bernstein et al. (2021) and Bach and Farrel (2018) used the SMI-R - Schema Mode Inventory-Revised (Lobbestael et al., 2010) of 118 items. Dunne et al. (2018) and Dunne et al. (2019) used the SMI version 1.1, a version with 124 items that, according to the authors, at the time of publication, had not yet had its psychometric properties published but was the most recent version indicated by the Schema Therapy Institute. Lewis et al. (2021) used this same version of SMI 1.1, and in the bibliographic references, they also do not mention a validation article; they only refer to the materials and inventories of the Schema Therapy Institute 2014 Version 2.0.

Vos et al. (2023) and Clercx et al. (2021) claim to have used the SMI-R. However, the latter describes the instrument as containing 80 items. Therefore, it is possible to infer that this is, in fact, the SMI-FV, a short and revised version, whose validation is described in the article by Keulen De-Vos et al. (2017), which, in turn, is among those selected for this systematic review. In this version of the SMI, the 80 items are related to the 16 schema modes (FIVE items for each schema mode) and are evaluated based on a Likert scale from 1 (never or almost never) to 6 (always).

Only the study by Gülüm AND Soygüt (2022) used the version of the SMI adapted for the forensic population, which the authors are still developing and validating. This is the Schema Mode Inventory-Forensic (SMI-F) with additional items specific to this population, totaling 174 items.

DISCUSSION

Initially, the index of agreement of the assessment of the quality of the selected articles stands out. There was no difficulty in identifying its main characteristics in the studies. Achieving high levels of agreement in the selection of works can be a complicated task, considering that not all articles make clear all the points required for their evaluation. In the literature, there are interpretations for kappa values, and these depend on the prevalence of the effect of interest and the way of classification by different reviewers. In this study, the agreement rate was 89%, considered moderate but satisfactory.

The results revealed several types of limitations in the studies. When the research was carried out in psychiatric or forensic institutions, the institutions previously selected the participants, thus leaving aside the most hostile and unstable individuals. Self-narrative instruments also raise the hypothesis of biased accounts inconsistent with reality, provided as socially desired responses or interposed by cognitive limitations, memory limitations, or feelings of guilt and shame.

It is also necessary to point out that the fact that most studies were carried out only with male individuals prevents generalization of the results. In the study by Lewis et al. (2021), the sample was homogeneous in terms of gender and country of origin, while in the study by Bach and Farrel (2018), the participants were from a specific region of Denmark characterized by a homogeneous sociodemographic profile.

Furthermore, one of the main limitations in case studies carried out with the forensic population is the principle of voluntariness. Bernstein et al. (2021) point out that previous studies have already raised questions about the effectiveness of coercive forensic treatment, as is the case with the types of treatment usually offered in the institution where their randomized clinical trial took place. However, participation in Bernstein et al.’s (2021) clinical trial was voluntary, and participants had the prerogative to withdraw without any consequences, demonstrating rare withdrawals and very satisfactory results.

In the case of these institutionalized patients, even when participation is voluntary, participants are chosen for convenience, as in the studies by Vos et al. (2023), Lewis et al. (2021), Bernstein et al. (2021), Clercx et al. (2021), and Dunne et al. (2019). The studies by Vos et al. (2023) and Lewis et al. (2021) were conducted in psychiatric hospitals, where patients with the research profile were invited. Participants who volunteered had to obtain permission from their psychiatrists or head nurses of their units, who checked whether the volunteers were mentally stable and their stress level at the time. In studies by Bernstein et al. (2021) and Clercx et al. (2021), participation was also voluntary, and the exclusion criteria were also related to mental instability, chemical dependency, and pedophilia.

In Dunne et al.’s (2019) study, participants were invited through notices and flyers spread throughout the prison. Twentyeight participants were excluded due to illiteracy, while those not proficient in the primary language of the research, English, were also rejected. The same invitation resources were used by Dunne et al. (2018); only those under 18 and those who did not know how to speak the primary language of the research (English) were not considered eligible.

In the study by Gülüm & Soygüt (2022), the sample was composed of university students who studied the same Psychology subject. Therefore, we can infer that some technical knowledge about the object of study may have interfered with the results. Furthermore, there was no differentiation of diagnostic conditions, and the sociodemographic profile was homogeneous.

Clercx et al. (2021) state that their hypotheses could not be confirmed because the effect of the correlation between emotional states and the risk of violence is small, which would require a much larger sample. Another limitation could be the possibility of this correlation only existing in a later treatment period or shortly after hospital admission. The average length of stay for participants was one and a half years, a period that may have already been used to treat maladaptive emotional states, which may have interfered with the results of this research.

In the study by Lewis et al. (2021), the questionnaire items were read aloud so that participants responded directly to the researcher. In the study by Dunne et al. (2019), participants answered the self-report instruments in the presence of up to four other participants in the same room, and in the study by Dunne et al. (2018) with the presence of up to five other participants, under the supervision of the PhD candidate responsible for the research. As it is sensitive content, the different forms of exposure may have impacted the participants’ responses. Dunne et al. (2019) also point out previous studies that identified a tendency in forensic patients to present themselves disproportionately favourably, which can affect research results.

Keulen De-Vos et al. (2017) corroborate this idea and, to minimize the effect of this bias on the results, they previously carried out a data analysis correlating the results of all inventories used (including the SMI) with the results of the BIRD (Balanced Inventory of Social Desirable Responding), an inventory that assesses social desirability. As a result, they reduced the sample by 10% to reduce the tendency of distorted reports.

Since Lewis et al. (2021) used an observation instrument, their results may have been impacted by the observers’ (nurses) bias regarding mood, comparison with other patients, and knowledge of the participants throughout the assessment. And because they were participants in psychiatric treatment, their health conditions may also have interfered with the results.

Vos et al. (2023) and Dunne et al. (2018) point out as a limitation in their studies that they are cross-sectional studies, which limits the possibility of making inferences about the real role of schematic modes in retrospective aggressive behaviors. Differently, Clercx et al. (2021) assessed follow-up after 6, 12, and 18 months. Follow-up could not be assessed in the clinical trial by Bernstein et al. (2021).

According to Lewis et al. (2021), who assessed the follow-up after two weeks, the Angry Child and Undisciplined Child modes were the most identified in aggressive behaviors, corroborating previous studies on this topic. There was no correlation between the schema modes identified in retrospective aggressive behaviors and the follow-up.

Golüm and Soygüt’s (2022) results pointed to the mediating role of anger-related modes, and the Vulnerable Child mode in the relationship between the Punitive Parent and Demanding Parent modes and psychological symptoms. However, the most expressive results are related to the Vulnerable Child mode as a mediator rather than the schema modes more directly related to anger. The authors also point out that anger is more related to the Punitive Parents mode, and this corroborates the theory that patients become their own abusive parents and punish themselves.

According to Dunne et al. (2019), the results showed correlations between the cognitive structures related to the aggression of the General Aggression Model (GAM), anger, DSM-5 personality traits, and schema modes. Anger traits are strongly associated with the three schema modes included in the study (Angry Child, Impulsive Child, and Bully-and-Attack), the aggression script is moderately associated with the Angry Child and Bully-and-Attack and little related to the Impulsive Child mode; normative beliefs of consent to aggression were moderately associated with the Angry Child and Bully-andAttack, and there was no correlation with the Impulsive Child mode. Hostility and Risk-taking were positively associated with the three schema modes.

CONCLUSION

This study aimed to list the ways the SMI can contribute to understanding aggressive behavior, a relevant topic to the well-being of society. We consider that this theoretical knowledge can support new empirical research and, in the future, new care protocols and more effective practices than those currently in force.

The research carried out indicates, initially, as we still lack a more incisive volume of scientific articles to support this claim, the viability of using the SMI as a predictor for the risk of violence and propensity for aggressive behavior, and its benefit within a process of long-term psychotherapy, along the lines of the ST, aiming at the rehabilitation of violent offenders with personality disorders. New longitudinal studies are necessary to confirm the relevance of identifying schema modes in predicting the risk of violence.

Therefore, studies that aim to understand the triggers of emotional dysregulation and impulsive behaviors are crucial, since theses aspects are directly related to aggressive behavior. Using the SMI to identify the schema modes that precede or are present in occasions involving violence provides self-knowledge that can be used to regulate emotions and control impulsivity.

This study points out the Impulsive Child, Angry Child, and Bully-and-Attack as the schema modes most related to aggressive behaviors. Recognizing schema modes allows a greater understanding of the circumstances that activate certain emotional states that cause discomfort and how these individuals self-learned to cope with discomfort with aggressive behavior, seeing in it some advantage over emotional discomfort. Therefore, recognizing the schema modes, the role of anger, and whether it is a primary or secondary emotion through the SMI can be a precursor act to discovering new possibilities for interventions in cases of violence.

Aggressive behaviors hide emotional needs. Therefore, without psychological intervention that identifies the emotional need hidden behind angry behavior, professionals who work with violent behaviors may have difficulty understanding and, consequently, dissuading these individuals from not recognizing aggressiveness as the only alternative to let out emotional discomfort.

The limitations of this systematic review are directly linked to the limits of the studies included in it. The fact that only nine studies were identified, most carried out in a forensic context, with male participants and a convenience sample, prevents generalization and greater assertiveness in describing the results. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest or funding.

Trabalho vencedor na categoria Monografia de Especialização do Prêmio Monográfico Bernard Rangé do ano de 2023

Funding source: No.

REFERENCES

Bach, B., & Farrell, J. M. (2018). Schemas and modes in borderline personality disorder: The mistrustful, shameful, angry, impulsive, and unhappy child. Psychiatry Research, 259, 323-329. [ Links ]

Bachrach, N., & Arntz, A. (2021). Group schema therapy for patients with cluster-C personality disorders: A case study on avoidant personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 1233-1248. [ Links ]

Baldissera, D., Paim, K., Predebon, B. M., & Feix, L. da F. (2021). Contribuições da Terapia do Esquema em relacionamentos conjugais abusivos: Uma revisão narrativa. PSI UNISC, 5(1), 51-67. [ Links ]

Bär, A., Bär, H. E., Rijkeboer, M. M., & Lobbestael, J. (2023). Early maladaptive schemas and schema modes in clinical disorders: A systematic review. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96(3), 716-747. [ Links ]

Barazandeh, H., Kissane, D. W., Saeedi, N., & Gordon, M. (2018). Schema modes and dissociation in borderline personality disorder/traits in adolescents or young adults. Psychiatry Research, 261, 1-6. [ Links ]

Bernstein, D. P., Arntz, A., & de Vos, M. (2007). Schema focused therapy in forensic settings: Theoretical model and recommendations for best clinical practice. The International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 6(2), 169-183. [ Links ]

Bernstein, D. P., Keulen-de Vos, M. E., Clercx, M., de Vogel, V., Kersten, G. C. M., Lancel, M., ... Arntz, A. (2023). Schema therapy for violent PD offenders: A randomized clinical trial. Psychological Medicine, 53(1), 88-102. [ Links ]

Bernstein, D., & Navot, L. (2023). Fazendo a ponte entre a prática clínica geral e a forense: Trabalhando no “aqui e agora” com modos de esquema difíceis. In G. Heath, & H. Startup (Orgs.), Métodos criativos na Terapia do Esquema: Avanços e inovação na prática clínica (pp. 207-223). Artmed. [ Links ]

Clercx, M., Keulen-de Vos, M. E., & Beurskens J. (2021). Healthy emotions, lower risk? The relationship between emotional states and violence risk among offenders with personality disorders. Journal of Forensic Psychology, Research and Practice, 21(1), 1-17. [ Links ]

Dahlberg, L. L., & Krug, E. G. (2006). Violence a global public health problem. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 11(2), 277-292. [ Links ]

Damasceno, E. S., Ferronatto, F. G., dos Santos, M. B., de Ávila, A. C., Tavares, M. E. A. M., & da Silva Oliveira, M. (2019). Resultados preliminares do Inventário de Modos Esquemáticos (SMI) em população geral. III Congresso Wainer de Psicoterapias Cognitivas, Gramado, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. [ Links ]

de Klerk, A., Keulen-de Vos, M. E., & Lobbestael, J. (2022). The effectiveness of schema therapy in offenders with intellectual disabilities: A case series design. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 47(3), 218-226. [ Links ]

Dunne, A. L., Gilbert F., Lee, S., & Daffern, M. (2018). The role of aggression-related early maladaptive schemas and schema modes in aggression in a prisoner sample. Aggressive Behavior, 44(3), 246-256. [ Links ]

Dunne, A. L., Lee, S., & Daffern, M. (2019). Extending the general aggression model: Contributions of DSM-5 maladaptive personality facets and schema modes. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(9), 1-34. [ Links ]

Ercole, F. F., Melo, L. S. D., & Alcoforado, C. L. G. C. (2014). Revisão integrativa versus revisão sistemática. Reme: Revista Mineira de Enfermagem, 18(1), 9-11. [ Links ]

Fassbinder, E., Brand-de Wilde, O., & Artnz, A. (2019). Case formulation in schema therapy: Working with the mode model. In U. Kramer (Ed.), Case formulation for personality disorders: Tailoring psychotherapy to the individual client (pp. 77-93). Academic Press. [ Links ]

Fiuza, W. M., & de Godoy, R. F. (2021). Esquemas iniciais desadaptativos em adultos brasileiros: Revisão narrativa da literatura. PSI UNISC, 5(2), 59-77. [ Links ]

Flanagan, C., Atkinson, T., & Young, J. (2023). Uma introdução à terapia do esquema: Origens, visão geral, status de pesquisa e direcionamentos futuros. In G. Heath, & H. Startup (Orgs.), Métodos criativos na Terapia do Esquema: Avanços e inovação na prática clínica (pp. 1-14). Artmed. [ Links ]

Fuchs, S. C., & Paim, B. S. (2010). Revisão sistemática de estudos observacionais com metanálise. Clinical and Biomedical Research, 30(3), 1-8. [ Links ]

Gülüm, İ. V., & Soygüt, G. (2022). Dysfunctional parenting and psychological symptomatology: An examination of the mediator roles of anger representations in the context of the schema therapy model. Psychological Reports, 125(1), 110-128. [ Links ]

Keulen-de Vos, M. E., Bernstein, D. P., Clark, L. A., de Vogel, V., Bogaerts, S., Slaats, M., & Arntz, A. (2017). Validation of the schema mode concept in personality disordered offenders. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 22(2), 420-441. [ Links ]

Koppers, D., Van, H., Peen, J., & Dekker, J. J. (2021). Psychological symptoms, early maladaptive schemas and schema modes: predictors of the outcome of group schema therapy in patients with personality disorders. Psychotherapy Research, 31(7), 831-842. [ Links ]

Lewis, D., Dunne, A. L., Meyer, D., & Daffern, M. (2021). Assessing schema modes using selfand observer-rated instruments: Associations with aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17-18), NP9908-NP9929. [ Links ]

Lobbestael, J., Van Vreeswijk, M., Spinhoven, P., Schouten, E., & Arntz, A. (2010). Reliability and validity of the short Schema Mode Inventory (SMI). Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 38(4), 437-458. [ Links ]

Maffini, G., Finoqueto, Y. O., & Cassel, P. A. (2020). Schematic modes in borderline personality disorders - Schema Therapy Approaches. Research, Society and Development, 9(8), e900986467. [ Links ]

Matos, F. R., Rossini, J. C., & Lopes, R. F. F. (2018). Schema Mode Inventory (SMI): Revisão de literatura. Revista Brasileira de Terapias Cognitivas, 14(2), 95-105. [ Links ]

Matos, F. R., Rossini, J. C., Lopes, R. F., & do Amaral, J. D. H. (2020). Translation, adaptation, and evidence of content validity of the Schema Mode Inventory. Psicologia: teoria e prática, 22(2), 39-59. [ Links ]

Nudelman, G., & Otto, K. (2020). The development of a new generic risk-of-bias measure for systematic reviews of surveys. Methodology, 16(4), 278-298. [ Links ]

Oettingen J, Rajtar-Zembaty A. (2022). Prospect of using schema therapy in working with sex offenders. Psychiatria Polska, 56(6), 1253-1267. [ Links ]

Oleśniewicz, M. (2021). Schema Therapy in the treatment of detention patients with antisocial personality structure. Effectiveness and management methods. Psychoterapia, 199(4), 21-34. [ Links ]

Salicru, S. (2023). The healthy adult in Schema Therapy: Using the octopus metaphor. Psychology, 14(6), 932-951. [ Links ]

Soygüt, G., Gülüm, İ.V., Ersayan, A. E., Lobbestael, J., & Bernstein, D. P. (2023). A preliminary psychometric study of the Turkish Schema mode inventory-forensic (SMI-F). Current Psychology, 42, 1140311414. [ Links ]

Vos, M. K., Giesbers, G., & Hülsken, J. (2023). Relationships between early maladaptive schemas and emotional states in individuals with sexual convictions. Sexual Abuse, 10790632231153635. [ Links ]

Westphalen, R. B., & Méa, C. P. D. (2018). Esquemas iniciais desadaptativos em indivíduos com diagnóstico de obesidade. XII Mostra de Iniciação Científica e Extensão Comunitária e X Mostra de Pesquisa de Pós-Graduação IMED, Passo Fundo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. [ Links ]

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2009). Terapia do esquema: Modelo conceitual. In J. E. Young, J. S. Klosko, & M. E. Weishaar, Terapia do esquema: Guia de técnicas cognitivo-comportamentais inovadoras (pp.17-69). Artmed. [ Links ]

Zhang, K., Hu, X., Ma, L., Xie, Q., Wang, Z., Fan, C., & Li, X. (2023). The efficacy of schema therapy for personality disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 77(7), 641-650. [ Links ]

Received: January 28, 2023; Accepted: October 03, 2023

texto em

texto em