Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho

versão On-line ISSN 1984-6657

Rev. Psicol., Organ. Trab. vol.20 no.2 Brasília abr./jun. 2020

https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2020.2.18204

Experiences of discrimination and inclusion of brazilian transgender people in the labor market

Experiências de discriminação e inserção de pessoas transgênero brasileiras no mercado de trabalho

Experiencias de discriminación e inserción de personas transgénero brasileñas en el mercado laboral

Angelo Brandelli CostaI; Gabriel Mendes BrumI; Ana Paula Couto ZoltowskiII; Luciana Dutra-ThoméIII; Maria Inês Rodriguês LobatoIV; Henrique Caetano NardiII; Silvia Helena KollerV,VI

IPontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS), Brasil

IIUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Brasil

IIIUniversidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Brasil

IVHospital das Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Brasil

VUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande (FURG), Brasil

VINorth-West University, África do Sul

Informations about the main author

ABSTRACT

Transgender women and men continue to encounter barriers, motivated by discrimination, in their daily lives and-although much less studied-in achieving a satisfactory career. The objective of this study is to describe transgender women's and men's labor market discrimination. A cross-sectional study was performed using data from 384 participants who identified as having a gender different than the one assigned at birth. Regarding their current work situations, 33.85% of transgender women and 45.16% of transgender men stated that they do not have a current occupation. A good extend reported having been denied a job opportunity because of their gender identity. Those who do get a job are exposed to discrimination and receive little or no social support from their colleagues and their bosses. The present research reinforces the necessity of policies to guarantee inclusion, and permanence of transgender people in the labor market.

Keywords: transgender people, work, discrimination

RESUMO

Mulheres e homens transgênero continuam a encontrar barreiras resultantes de discriminação em sua vida cotidiana e na busca de uma carreira satisfatória - esta última muito menos estudada. O objetivo deste estudo é descrever a discriminação de mulheres e homens transgênero no mercado de trabalho. Realizou-se estudo transversal com 384 participantes que se identificaram como tendo um gênero diferente daquele que lhe foi atribuído no nascimento. Em relação à situação atual de trabalho, 33,85% das mulheres transgênero e 45,16% dos homens transgênero afirmaram não possuir ocupação atual. Parte dos participantes relatou ter sido recusada uma oportunidade de emprego por causa de sua identidade de gênero. Aqueles que conseguiram um emprego são expostos à discriminação e recebem pouco ou nenhum apoio social de seus colegas e chefes. A presente pesquisa reforça a necessidade de políticas que garantam a inclusão e permanência de pessoas transexuais no mercado de trabalho.

Palavras-chave: pessoas transgênero, trabalho, discriminação, inclusão

RESUMEN

Las mujeres y los hombres transgénero continúan encontrando barreras en su vida diaria, motivadas por la discriminación, aunque mucho menos estudiadas, para lograr una carrera satisfactoria. El objetivo de este estudio es describir la discriminación en el mercado laboral de mujeres y hombres transgénero. Se realizó un estudio transversal con 384 participantes que identificaron un género diferente al asignado al nacer. Con respecto a situaciones laborales actuales, el 33.85% de las mujeres transgénero y el 45.16% de los hombres transgénero declararon que no tenían una ocupación actual. Una buena proporción informó que le negaron una oportunidad de trabajo debido a su identidad de género. Aquellos que tenían un trabajo fueron expuestos a la discriminación y recibieron poco o ningún apoyo social de sus colegas y sus jefes. La presente investigación refuerza la necesidad de políticas para garantizar la inclusión y la permanencia de las personas transgénero en el mercado laboral.

Palabras-clave: personas transgénero, trabajo, discriminación, inclusión.

In Brazil, the high degree of prejudice against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations is well known (Costa, Peroni, de Camargo, Pasley, & Nardi, 2015). According to the Trans Murder Monitoring Project, Brazil has one of the highest transgender-related homicide rates in the world (Balzer/LaGata & Berredo, 2016). In addition to explicit violence, transgender populations continue to encounter barriers, motivated by direct or indirect discrimination, in accessing healthcare services (Costa et al., 2018) and-although much less studied-in achieving a satisfactory career (Brown et al., 2012; Scott, Belke, & Barfield, 2011).

For transgender individuals, the long trajectory of labor discrimination began at school. Accordingly, most transgender youth from the United States disclosed feeling unsafe at school because of their gender identity (Grossman et al., 2009; Kosciw, Greytak, Giga, Villenas, & Danischewski, 2016). They also reported high levels of school victimization, ranging from verbal to physical violence (Day, Perez-Brumer, & Russell, 2018; Grossman et al., 2009). Not surprisingly, a hostile school environment has many deleterious outcomes on transgender youth academic success and engagement in the labor market (Birkett, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009; Greytak, Kosciw, Villenas, & Giga, 2016; Kosciw et al., 2016). Therefore, starting at the school level, transgender people face multiple obstacles to their work trajectory (Carvalho, 2015; Sausa, Keatley, & Operario, 2007). The educational losses caused by dropping out of school can result in an even more fragile inclusion in the labor market. In addition to bullying at school, transgender people are also confronted with negative stereotypes related to transgender women seen as sex workers, which is reflected even in programs and public policies that target this population (Carvalho, 2015; Pelúcio, 2011; Pelúcio & Miskolci, 2009;). The necessity of fulfilling social roles by choosing activities predominantly considered masculine or feminine may also aggravate their inclusion into the job market (Brown et al., 2012; Evans & Diekman, 2009). Furthermore, waiting for the realization of social and medical gender-affirming processes may delay the start of professional activity (Budge, Tebbe, & Howard, 2010).

This study, and the survey that was used for data collection, are informed by the minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003). This theory was developed to understand the specific stressors in the form of discriminations that affect sexual minorities. It comprises three factors: the direct experience of discrimination, the anticipation of discrimination, and the internalization of prejudice. In addition to gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual people, the theory has been successfully applied to transgender individuals (Hendricks & Testa, 2012). Direct and indirect experiences of stigma and discrimination are still the primary barriers to the professional development of transgender populations. Discrimination in the workplace can present itself on a microystemic level (e.g., microaggression, oppression among peers, lack of support from people close to them), a mesosystemic level (e.g. the specific social- or professional group the transgender individual is inserted in), or a macrosystemic level (e.g., maladaptation of the health system, educational institutions, public policies). This discrimination increases the levels of anxiety, depression, apprehension and interpersonal difficulties among transgender people (Brown et al., 2012; Budge et al., 2010; Dispenza, Watson, Chung, & Brack, 2012).

Despite the importance of having a job and a satisfying career, the relationship between gender identity and career development has been poorly researched and remains a still-emerging area of study (Chung, 2003; Hill et al., 2017). It has been observed that for the LGBT populations, enacted, perceived and anticipated discrimination play a fundamental role in career choice and work-adjustment (Schneider & Dimito, 2010). Among the various career development theories, Gottfredson's (1996) circumscription theory has been proved useful in investigating the relationships between gender identity and career development, especially by considering the influence of discrimination (Gottfredson, 1996).

Gottfredson (1996) proposed that individuals make professional choices through a process of eliminating options and narrowing choices. During their career development, people tend to reject occupations that: a) are incompatible with their gender, b) are perceived as inappropriate to their social class and skill level, and c) do not fit their interests and values. Individuals, then, construct a cognitive map of occupations that are regarded as potentially viable. This process, which leads to the delimitation of professions acceptable to the individual, is called "circumscription" (Gottfredson, 1996). Occupational preferences are presented as the result of the compatibility between the accessibility judgments and the perceived occupations. Accessibility refers to obstacles or opportunities in the social context that affect a person's chances of securing a particular occupation. Perceptions of accessibility are based on factors such as assessment of an occupation in a preferred geographical area and anticipation of discrimination. Because occupations are not always accessible, concessions must be made. In general, the typical pattern of concessions involves first sacrificing interests, then prestige, and finally, giving in to sexual typing. The process by which the individual gives up preferred career aspirations when they do not coincide with work or training opportunities is referred to as "commitment" (Gottfredson, 1996). Therefore, transgender individuals face a professional trajectory full of particularities and very specific challenges that must be considered in order to improve their access to job opportunities. In this context, the objective of the current study is to describe transgender individual's experiences of discrimination and inclusion in the labor market.

Method

Participants

Seven hundred and one volunteers were approached to answer the overall study. Of them, 384 transgender people answered the questions related to the present study. The mean age of the participants was 26.79 years (SD = 8.78). Most of the sample (53.22%) consisted of emerging adults (ages between 18 and 24 years). Additional sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Instruments

The instrument used in this study was an adapted version of the survey used in the TransPULSE project (TransPULSE, 2012), which was one of the first large-scale studies to address the health needs and vulnerabilities of transgender populations and their barriers to healthcare access. The TransPULSE survey was translated and adapted to Portuguese, specifically for use among Brazilian transgender people. The translation and adaptation were carried out by a group of health practitioners who work in gender and sexual diversity fields, and assessed by members of the trangender communities in Brazil. The procedure for cross-cultural adaptation was based on the International Test Commission (2017), according to the following steps: (1) contextual equivalence and review by expert committee; (2) translation; (3) evaluation by the target audience; and (4) evaluation by the original authors of the instrument. The major changes in the instrument were related to the specificities of the Brazilian public healthcare system, the racial/ethnic background of the target population, and the inclusion of the Brazilian cultural-specific gender identity travesti (see below). In the present study, the assessed sociodemographic variables were gender identity, number of inhabitants in the participant's city of residence, ethnicity and educational level. Gender identity was evaluated using the two-question method (sex assigned at birth and current gender identity), and subjects were considered eligible to participate if they reported a gender different from that assigned to them at birth (Reisner et al., 2014). Organized social movements in Brazil prefer the terms travesti, transsexual and trans person (man or woman) to the Anglophone umbrella term transgender (Carvalho, 2018; Carvalho & Carrara, 2013). Travesti is a culturally specific gender identity term used in Brazil (Barbosa, 2013). Based on their self-reported gender identity, participants were re-categorized as transgender women, transgender men or gender-diverse persons. Transgender women were those who were designated male at birth but identified as women, trans women or travestis. Transgender men were those designated female at birth, but identified as men or trans men, whereas gender-diverse persons people were those who identified with a gender outside the gender binarism. Gender-diverse persons were excluded from the present analysis.

Ethnicity was assessed using the census categories of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics: white, black, Asian (mostly East Asians), and indigenous. The category pardo was also used, which commonly refers to Brazilians of mixed race, typically a mixture of white, Afro- and native Brazilian.

Variables related to the participants' current occupation (according to International Labor Organization [ILO] International Standard Classification of Occupations [ISCO 08]): clerical support workers (e.g., typist, customer service); services and sales workers (e.g., aesthetics, hair, makeup, waitress/waiter, kitchen, personal care, safety); technician and associate professionals (e.g., administration, informatics, law, culture, health, science, engineering); professionals (e.g., education, computer science, law, culture, health, science, engineering); skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers; craft and related trades workers (e.g., clothing, food, building, painting, electronics, metals); plant and machine operators and assemblers (e.g., machine operator, driver, factory worker); managers (e.g., executive, administrator); armed forces occupations (e.g., military, police); and elementary occupations (e.g., cleaning assistant, kitchen assistant, sex work, street work, garbage collection, mining)

Current employment status was evaluated by a multiple-choice question created with the input of the Brazilian transgender community during the validation process. The idea of this question is to assess less formal occupation and employment statuses not encompassed by the ILO classification. Participants needed to answer if they consider themselves unemployed, an employee, self-employed / entrepreneur, student or trainee, housewife/househusband, doing informal work, receiving help from third parties, doing voluntary work, receiving unemployment benefit, receiving invalidity or sickness benefit, and/or being retired.

Participants were also asked about work satisfaction: "are you working in your preferred field?" and reasons for not working in a preferred field. Finally, participants answered about discrimination and social support related to their gender identity in their workplace, as well as reasons for engaging in paid sexual relationships.

Data Collection Procedures and Ethical Considerations

Data were collected in two Brazilian states: Rio Grande do Sul and São Paulo. Both states have gender identity programs that provide gender-affirming surgery at university hospitals (which are public in Brazil). Because the Brazilian National Health System provides georeferenced care, patients seeking gender affirmation must undergo these procedures in the states in which they live. Transgender people who attended these programs were invited to voluntarily answer an electronic version of the survey, using a tablet, from January to June 2014. The questionnaire was also available on the Internet through an online Facebook announcement targeting transgender populations during two time periods: July-October 2014 and January-March 2015. At the time of data collection, the hospitals considered in this study were the only ones in the two states providing gender-affirming care. We asked the participants in the online sample if they were currently receiving care at the hospitals and excluded those who answered affirmatively. Since there were no statistically significant differences in the results of the survey between the sample of participants attending programs of gender affirmation and the sample of participants reacting to the Facebook announcement, they were combined in the analyses reported in the Results section.

This study was approved by the institutional review board and the Human Ethics Committees of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA) and Instituto de Psiquiatria do Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo (IPQ-USP). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Analysis Procedures

Descriptive analyses of all variables (frequency and percentages) were calculated for the two groups: transgender men and transgender women. We present the results in the following order, sociodemographic characteristics, current occupation based on ILO criteria, current work condition, satisfaction with work and reasons for not working in a preferred field, discrimination and social support in the workplace and finally sex-work contexts and motivations.

The differences between the two groups (transgender men and transgender women) were calculated using chi-square or-where appropriate-Student's t-test. P-values are listed for all the chi-square and t-test calculations For the effect sizes of the t-tests, Cohen's d was calculated and for the chi-square, Cramer's V was used.

Results

As shown in Table 2, most frequently participants reported not having a current occupation, with 33.85% of transgender women and 45.16% of transgender men not currently working. Of those working, the most prevalent area of employment was services and sales, with 16.15% of transgender women and 7.92% of transgender men working in this field, followed by elementary occupations with 16.15% of transgender women and 7.44% of transgender men. Concerning education, for the combined sample, 17.89% had some level of higher education, and 64.58% had completed secondary school.

Regarding current employment status (Table 3), even when there was a possibility of choosing a more flexible occupational status, 25% of transgender women and 29.03% of transgender men declared themselves unemployed. Differences were found by gender among those who declared themselves to be self-employed (more transgender women), students or trainees (more transgender men) and housewives/househusbands (more transgender women).

Regarding satisfaction with work, 36.15% of transgender women and 26.61% of transgender men reported that they were not working in their preferred field. As described in Table 4, the most frequently reported reason (42.17% of transgender women and 59.14% of transgender men) was lack of required educational level or qualifications, followed by fear of discrimination (35.15% of transgender women and 27.95% of transgender men) and having previously experienced discrimination (22.29% of transgender women and 16.13% of transgender men).

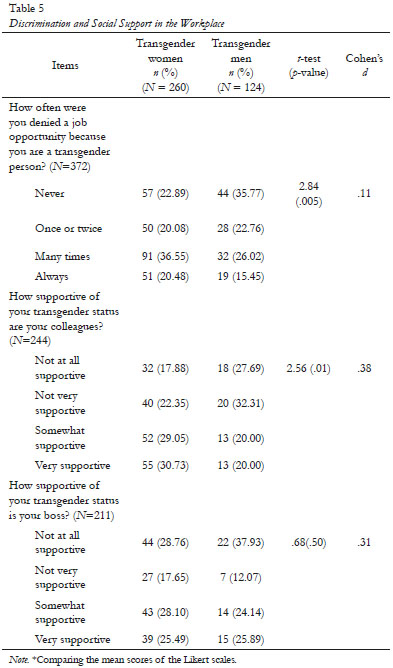

28.20% (n=66) of transgender women and 29.91% (n=32) of transgender men reported being a victim of discrimination in the workplace. There were no statistically significant differences between trans men and women (chi-square = .10, p = .75, Cramer's V = .02). As shown in Table 5, regarding discrimination at the workplace, 77.11% of transgender women and 64.23% of transgender men reported being denied a job opportunity at least once in their lifetime because of being transgender, that difference was statistically significant.

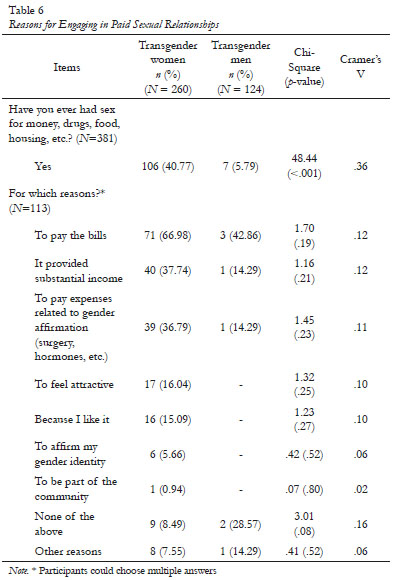

Participants were also asked if they had previously engaged in sexual relations in exchange for money, housing, drugs, food or other needs. Among transgender women, 40.77% answered yes, compared to 5.79% of transgender men. Those who answered positively were further asked about the reasons that led them to do it; the participants were able to select more than one option. As shown in Table 6, financial reasons are the most prevalent: 66.98% of transgender women and 42.86% of transgender men reported having engaged in sex work to pay the bills; 37.74% of transgender women and 14.29% of transgender men reported engaging in sexual relations because it provided substantial income; and 36.79% of transgender women and 14.29% of transgender men disclosed engaging in sexual relations to pay expenses related to transsexuality (hormones, surgery, etc.).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first Brazilian study to describe the inclusion of transgender people in the labor market. A high prevalence of unemployment, underemployment, and dissatisfaction with the current occupation was found. One of the most relevant findings was that 33.85% of transgender women and 45.16% of transgender men reported that they were not currently working (Table 2). In comparison, in December 2014 Brazil reached the lowest unemployment rate in its history, with 4.30% of the general population unoccupied (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), 2015).

Although the lack of a relevant qualification was the most prevalent reason for fear of discrimination, previous experiences of discrimination were another important justification for not engaging in a satisfying profession. Results reinforce the conclusion that discrimination leads to access barriers to employment in ways that are both objective (e.g., having actually been exposed to discrimination) and subjective (e.g., anxiety and fear about future discrimination experiences) (Brown et al., 2012; Budge et al., 2010; Dispenza et al., 2012). Discrimination (either anticipated or experienced) is an important obstacle that transgender people regularly face when accessing specific professional activities. It negatively affects work satisfaction and results in stress and anxiety (Dispenza et al., 2012). It is noteworthy that having more formal education than the general population is not enough for the transgender sample to overcome situations of discrimination and find a satisfying job. In our sample, 17.89% had some level of higher education, and 64.58% had completed secondary school. These are considerably higher in comparison to the Brazilian general population, whose percentages are 13.50% for higher education and 26.40% for secondary school (IBGE, 2016). This is also true even when compared with the LGB community. Although there is still no data from Brazil, discrimination in employment was higher in transgender individuals comparing to cisgender LGBQ in a sample of 3,838 individuals from the United States (Kattari, Whitfield, Walls, Langenderfer-Magruder, & Ramos, 2016).

Our results suggest that the "circumscription" process (Gottfredson, 1996) for transgender women and transgender men is marked by educational gaps and discrimination as obstacles that hinder the accessibility of employment. Most do not have a job, as the present study shows a good extent of transgender men and women reported having been denied a job opportunity because of their gender identity. Roughly half of the participants who did get a job reported receiving at least some level of support from bosses and colleagues, while the other half reported receiving little or no support (Table 5).

Another finding from our data is that transgender women are more frequently denied a job at least once in their lifetime than transgender men. This aspect was already reported in qualitative studies in Brazil (Baggio, 2017) and the United States (Sevelius, 2013). In this regard, in line with previous international literature, transgender women were found to be more discriminated than transgender men (Bradford, Reisner, Honnold, & Xavier, 2013). However, our findings show that transgender men reported suffering a lack of support from colleagues and bosses, working less in their preferred areas and are more frequently currently unemployed than transgender women.

Our data appears to support Gotterson's (1996) hypothesis that limited work accessibility encourages transgender women and men to make concessions. At first, they appear to sacrifice interests, aspirations, prestige and, ultimately, aspects of their gender identity. Some choices of work appear to be curtailed by discrimination to the point that sex work becomes a feasible alternative to obtain money. Accordingly, economic necessities were often reported as the reason for engaging in sex work: doing it to "pay the bills"; doing it because it "provided substantial income"; and "to pay expenses related to transsexuality." There are no indications that participants of this study engaged in paid sexual activity due to career interests and values.

Survival sex work is a term that has been promulgated to identify sex exchanged for money or other commodities as a means of basic subsistence (Shannon et al., 2007). As we described elsewhere (Fontanari et al., 2018), the choice to engage in sex work must be understood in the context of a Brazilian nation where sex work is not criminalized but legislation prevents it from being institutionalized (pimping and specific houses for prostitution) (Bindman, 1997). It is unregulated and there are no support mechanisms or educational resources to ensure the safety of individuals who engage in the practice. As a result, sex workers are often vulnerable (Garcia, 2008; Operario, Soma, & Underhill, 2008). While the authors believe that the right to practice sex work should be guaranteed, we recognize that in some Brazilian contexts - such as the present research - survival sex work is a product of lack of choice and lack of support in other aspects of transgender women's lives.

Another aspect concerns the participants who declare themselves to be autonomous or individual entrepreneurs. Chung (2003) reports that the coping strategies most used by lesbian, gay and bisexual people in the labor market involve being autonomous. This becomes prominent due to the difficulty of getting and staying in formal employment. The same may be the case for the transgender people from our sample, since paying the bills was the most frequent answer for practicing sex work.

The present study has some limitations. First, the sample used in this research was not representative of all Brazilian states; consequently, national estimates based on these data could be biased. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the educational level of the sample is higher than the Brazilian average, and less educated transgender people may face additional barriers in accessing job opportunities. Therefore, these findings may be better than those one could expect to find in the general transgender populations. Since a little more than half of the participants are of emerging adult ages (between 18 and 24 years old), it is possible that several of those who reported not to be currently working are higher education students, an issue that is not investigated in this article.

Career counseling for transgender populations is still incipient. This study aimed to contribute to a description of transgender individual's work possibilities and previous experiences. Unfortunately, at least for transgender women and men, work, career development and discrimination are highly connected. In this unfortunate context, counseling could help to expand potential career trajectories and to help transgender people to address experiences with discrimination (Budge et al., 2010). Finally, public policies and legal protection against gender discrimination in the workplace are essential to include these populations. Alternatives are the creation of inclusive educational services and the adoption of quotas in professional vacancies in private companies and in the public sector.

References

Baggio, M. C. (2017). About the relation between transgender people and the organizations: new subjects for studies on organizational diversity. REGE-Revista de Gestão, 24(4),360-370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rege.2017.02.001 [ Links ]

Balzer/LaGata, C. & Berredo, L; (2016). Transrespect versus Transphobia Worldwide (TvT) c /o Transgender Europe (TGEU). Retrieved from https://transrespect.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/TvT-PS-Vol14-2016.pdf [ Links ]

Barbosa, B. C. (2013). "Freaks and whores": uses of travesti and transsexual categories ["Doidas e putas": usos das categorias travesti e transexual]. Sexualidad, Salud Y Sociedad-Revista Latinoamericana, 14, 352-379. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-64872013000200016 [ Links ]

Bindman, J (1997). Redefining Prostitution as Sex Work on the International Agenda. Retrieved from http://www.walnet.org/csis/papers/redefining.html [ Links ]

Birkett, M., Espelage, D. L., & Koenig, B. (2009). LGB and Questioning Students in Schools: The Moderating Effects of Homophobic Bullying and School Climate on Negative Outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7),989-1000. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/204637926?accountid=8034 [ Links ]

Bradford, J., Reisner, S. L., Honnold, J. A., & Xavier, J. (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10),1820-1829. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796 [ Links ]

Brown, C., Dashjian, L. T., Acosta, T. J., Mueller, C. T., Kizer, B. E., & Trangsrud, H. B. (2012). The career experiences of male-to-female transsexuals. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(6),868-894. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000011430098 [ Links ]

Budge, S. L., Tebbe, E. N., & Howard, K. A. S. (2010). The work experiences of transgender individuals: Negotiating the transition and career decision-making processes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(4),377-393. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020472 [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. (2015). Muito Prazer, Eu Existo! Visibilidade e reconhecimento no ativismo de pessoas trans no Brasil. (Doctoral dissertation, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro). Retrieved from http://www.bdtd.uerj.br/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=8975 [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. (2018). "Travesti", "mulher transexual", "homem trans" e "não binário": interseccionalidades de classe e geração na produção de identidades políticas. ["Travesti", "mulher transexual", "homem trans" e "não binário": interseccionalidades de classe e geração na produção de identidades políticas]. Cadernos Pagu, 52, e185211. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809444920100520011 [ Links ]

Carvalho, M., & Carrara, S. (2013). Towards a Trans future? Contributions to a history of the travesti and transsexual movement on Brasil. [Em direção a um futuro trans? Contribuição para a história do movimento de travestis e transexuais no Brasil]. Sexualidad, Salud Y Sociedad-Revista Latinoamericana, 14, 319-351. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-64872013000200015 [ Links ]

Chung, Y. B. (2003). Career counseling with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered persons: The next decade. The Career Development Quarterly, 52(1),78-86. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2003.tb00630.x [ Links ]

Costa, A. B., da Rosa Filho, H. T., Pase, P. F., Fontanari, A. M. V., Catelan, R. F., Mueller, A., ... Koller, S. H. (2018). Healthcare Needs of and Access Barriers for Brazilian Transgender and Gender Diverse People. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(1),115-123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0527-7 [ Links ]

Costa, A. B., Peroni, R. O., de Camargo, E. S., Pasley, A., & Nardi, H. C. (2015). Prejudice toward gender and sexual diversity in a Brazilian Public University: prevalence, awareness, and the effects of education. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(4),261-272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0191-z [ Links ]

Day, J. K., Perez-Brumer, A., & Russell, S. T. (2018). Safe schools? Transgender youth' s school experiences and perceptions of school climate. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 1731-1742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0866-x [ Links ]

Dispenza, F., Watson, L. B., Chung, Y. B., & Brack, G. (2012). Experience of Career-Related Discrimination for Female-to- Male Transgender Persons: A Qualitative Study. The Career Development Quarterly, 60(1),65-81. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2012.00006.x [ Links ]

Evans, C. D., & Diekman, A. B. (2009). On motivated role selection: Gender beliefs, distant goals, and career interest. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(2),235-249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01493.x [ Links ]

Fontanari, A. M. V., Rovaris, D. L., Costa, A. B., Pasley, A., Cupertino, R. B., Soll, B. M. B., ... & Bau, C. H. D. (2018). Childhood maltreatment linked with a deterioration of psychosocial outcomes in adult life for southern Brazilian transgender women. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(1),33-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0528-6 [ Links ]

Garcia, M. R. V. (2008). Prostitution and illegal activities among low-income travestis [Prostituição e atividades ilícitas entre travestis de baixa renda]. Cadernos de Psicologia Social do Trabalho, 11(2),241-256. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-37172008000200008&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Gottfredson, L. S. (1996). Gottfredson's theory of circumscription and compromise. In. D. Brown & L. Brooks (Eds), Career Choice and Development (pp. 179-232). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Greytak, E. A., Kosciw, J. G., Villenas, C., & Giga, N. M. (2016). From Teasing to Torment: School Climate Revisited. A Survey of US Secondary School Students and Teachers. New York: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). Retrieved from https://www.glsen.org/article/teasing-torment-school-climate-revisited-survey-us-secondary-school-students-and-teachers [ Links ]

Grossman, A. H., Haney, A. P., Edwards, P., Alessi, E. J., Ardon, M., Howell, T. J., ... Haney, A. P. (2009). Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth talk about experiencing and coping with school violence: A qualitative study. Journal of LGBT Youth, 6(1),24-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361650802379748 [ Links ]

Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5),460-467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597 [ Links ]

Hill, B. J., Rosentel, K., Bak, T., Silverman, M., Crosby, R., Salazar, L., & Kipke, M. (2017). Exploring individual and structural factors associated with employment among young transgender women of color using a no-cost transgender legal resource center. Transgender health, 2(1),29-34. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0034 [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) (2015). Indicadores IBGE: Pesquisa Mensal de Emprego - Janeiro 2015. Retrieved from https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/231/pme_2015_jan.pdf [ Links ]

International Test Commission (ITC). (2017). The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests. Retrieved from www.InTestCom.org [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2016). Pesquisa nacional por amostra de domicílios: síntese de indicadores. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. Retrieved from https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv98887.pdf [ Links ]

Kattari, S. K., Whitfield, D. L., Walls, N. E., Langenderfer-Magruder, L., & Ramos, D. (2016). Policing gender through housing and employment discrimination: comparison of discrimination experiences of transgender and cisgender LGBQ individuals. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7(3),427-447. https://doi.org/10.1086/686920 [ Links ]

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Giga, N. M., Villenas, C., & Danischewski, D. J. (2016). The 2015 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation's Schools. New York: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network. Retrieved from https://www.glsen.org/article/2017-national-school-climate-survey [ Links ]

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological bulletin, 129(5),674-697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [ Links ]

Operario, D., Soma, T., & Underhill, K. (2008). Sex work and HIV status among transgender women: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 48(1),97-103. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816e3971. [ Links ]

Pelúcio, L., & Miskolci, R. (2009). The Prevention of Deviance: the aids apparatus and the repatologization of dissent sexualities [A prevenção do desvio: o dispositivo da aids e a repatologização das sexualidades dissidentes]. Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad-Revista Latinoamericana, 1, 125-157. Retrieved from http://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/SexualidadSaludySociedad/article/view/29/133 [ Links ]

Pelúcio, L. (2011). Social markers of difference in the experiences of transvestites coping with AIDS [Marcadores sociais da diferença nas experiências travestis de enfrentamento à aids]. Saúde e Sociedade, 20(1),76-85. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-12902011000100010 [ Links ]

Reisner, S. L., Conron, K. J., Tardiff, L. A., Jarvi, S., Gordon, A. R., & Austin, S. B. (2014). Monitoring the health of transgender and other gender minority populations: validity of natal sex and gender identity survey items in a US national cohort of young adults. BMC Public Health, 14(1),1224. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1224 [ Links ]

Sausa, L. A., Keatley, J., & Operario, D. (2007). Perceived risks and benefits of sex work among transgender women of color in San Francisco. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(6),768-777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9210-3 [ Links ]

Schneider, M. S., & Dimito, A. (2010). Factors influencing the career and academic choices of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(10),1355-1369. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2010.517080 [ Links ]

Sevelius, J. M. (2013). Gender affirmation: A framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles, 68(11-12), 675-689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0216-5 [ Links ]

Shannon, K., Bright, V., Allinott, S., Alexson, D., Gibson, K., & Tyndall, M. W. (2007). Community-based HIV prevention research among substance-using women in survival sex work: the Maka Project Partnership. Harm Reduction Journal, 4(1),20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-4-20 [ Links ]

Scott, D. A., Belke, S. L., & Barfield, H. G. (2011). Career development with transgender college students: implications for career and employment counselors. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48(3),105-113. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2011.tb01116.x [ Links ]

TransPULSE (2012). Provincial Survey. Retrieved from http://transpulseproject.ca/wp-content/uploads/201 [ Links ]

Informations about the main author:

Informations about the main author:

Angelo Brandelli Costa

Av. Ipiranga, 6681 - Prédio 11, sala 933

Porto Alegre - RS -- Brasil, CEP 90619-900

E-mail: angelo.costa@pucrs.br

Submission: 09/05/2019

First Editorial Decision: 15/01/2020

Final Version: 14/02/2020

Accepted: 19/02/2020

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI