Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

versão impressa ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. v.41 n.1 Porto Alegre abr. 2007

LAS PERSPECTIVAS INTERNACIONALES EN EL ESTIGMA DEL SIDA

Similar epidemics with different meanings: understanding AIDS stigma from an international perspective

Nelson Varas Díaz1; José Toro-Alfonso

University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico

"AIDS occupies such a large part in our awareness because of what it has been taken to represent. It seems the very model of all the catastrophes privileged populations feel await them."

(Susan Sontag, 2001)

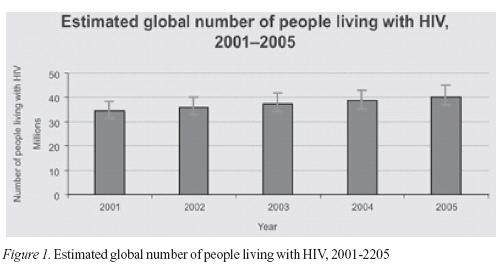

The HIV/AIDS have had a devastating impact in the world since its initial reported cases in 1983. The total number of people living with HIV at the end of 2005 is estimated in 40.3 millions with 4.9 new infections for that period (UNAIDS, 2005a). Figure 1 shows the estimated global number of people living with HIV from 2001 to 2005. Even though this numbers area astonishing, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, 2005b) has tried through its reports to identify strengths and successes in the fight against the epidemic and has stated that the HIV infection rates have decrease in certain countries. However the United Nations have also reported that "overall trends in HIV transmission are still increasing…" (p. 1).

Rates of HIV infection range from .01% in some countries in Eastern Europe (Poland) and Australia, to .07% in Argentina, .06% in the United States, 1.7% in Surinam and the Dominican Republic; to 5.6% in Haiti. This information might be underestimated due to the fact that surveillance is not done systematically in many countries (UNAIDS/WHO, 2004). The unequivocal fact is that the HIV/AIDS epidemic still disproportionably affects all countries in all regions of the world. In most countries minorities and marginalized populations are most affected; in the United States an estimated 40,000 people have been infected with HIV each year during the last decade. The epidemic is disproportionately lodged among Africa-American and Latino population, affecting mostly women (UNAIDS/WHO, 2004).

Sexual transmission is the most frequent infection route in most countries. With the exception of some countries, most of the HIV infection is related to unprotected intercourse. Most of the countries in the Caribbean, South America, United States, Canada, and Australia report high cases of sexually-transmitted infection either by heterosexual or homosexual unprotected intercourse. Some countries in Europe including Spain, the Russian Federation, and Poland report a higher number of infection related to injection drug use. A high number of AIDS cases in the northeastern part of the United States are also due to sharing unclean needles for intravenous drug use, especially among minority populations (Cáceres, 2004, UNAIDS/WHO, 2004).

Issues of access to care and prevention information are constantly discussed among health care providers and government officials. Besides the fact that many countries do have access to antiretroviral treatments, there are some regions where treatment and care are not accessible by most of the affected population. The high cost of treatment and the sophistication sometimes required for the administration of antivirals, make it difficult for disfranchised populations like the homeless and poorly educated patients in most of the America's.

The Roles and Limitations of Culture

Although the geographical contexts are different, it seems that there is ample evidence that culture and geography do play an important role in the way people conceive health and sickness. Access to health information and the development of a healthy sexual lifestyle are deeply interconnected to personal and cultural values (Valdiserri, 2002). But, "beyond the core or internalized influence related to race, ethnicity, and culture, sexuality is also affected by the attitudes of society as a whole" (Gómez, Mason, & Alvarado, 2005, p. 87). The global numbers of people living with AIDS and the rate of HIV infection remind us more of the role of our cultures, than of personal or individual vulnerabilities.

Be it through the culture of ethnicity, poverty or political environment, culture represents the social context of meaning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Duffy, 2005; Ogden & Nyblade, 2005). Globally, issues of sexuality, homosexuality, drug use or even premarital sex are still taboos associated with marginalized communities. Stigma and discrimination are part of complex systems of beliefs about illness and disease that are often grounded in social inequalities (Castro & Farmer, 2005).

Due to the social meanings attached to the epidemic, HIV produces social limitations which are mostly based on silence and invisibility. "HIV provides a unique opportunity, a window to explore the territories of secrecy, morality, and silence" (Klitzman & Bayer, 2003, p. 3). The truth of living with HIV is a constant reminder of the lack of acceptance and rejection found in our societies. Living with HIV demands silence and secrecy, because even in the best of cases people perceive rejection and lack of acceptance even from health care providers, including psychologists.

AIDS is a disease of social meaning (Varas-Diaz, Toro-Alfonso, & Serrano-García, 2005). Among other factors, this social meaning is disseminated through culture and the mass media that presents the epidemic as intimately associated to death and sickness; to the invisible lives of other people. In open contrast to other diseases portrayed by the media as generators of sympathy and motivation, AIDS is mostly presented as evidence of decadence and deterioration (Varas-Diaz & Toro-Alfonso, 2003). There are no attractive or romantic metaphors associated to AIDS (Sontag, 2001).

Stigma beyond Borders: International Perspectives on Stigma

The discreditable nature of people living with HIV/AIDS is based in the constant reminder that the information about their seropositive status could easily be identified by others (Goffman, 1963). The constant hyper-vigilance of living with the infection transcends geographical borders and cultures as is demonstrated by all the articles included in this special issue. Stigma and discrimination go beyond the borders established by languages, cultures, and sexualities.

Stigma can lead to discrimination and other violations of human rights which affect the well-being of people living with HIV in fundamental ways. In countries all over the world, there are well-documented cases of people living with HIV being denied the rights to healthcare, work, education, and freedom of movement, among others (Aggleton, Wood, Malcolm, & Parker, 2005). HIV-related stigma is also associated to economic and ethnic discrimination which co-exist to worsen the lives of people living with the disease.

The fact that stigma transcends borders presents us with an international challenge. As the HIV/AIDS epidemic continues to grow and impact the most vulnerable populations in our countries we need to identify and develop a global response. Stigma and discrimination combine non-normative behaviors which are usually criminalized by uneven power relations. An international review of the impact of stigma evidences the combination of stigma with disease, poverty, gender, social class, and nationality. Be it either HIV or Hepatitis C, located in the north or south of the America's, at the East of Europe or the Greater Caribbean, or in Australia; the testimonies and scientific evidence on the detrimental social and health implications of stigma is vast. As gender and sexuality become the target for exclusion, we will find women and sexual minorities separated and discriminated just for being who they are.

UNAIDS identified early in the epidemic the need for a global response to stigma as one of the most important prevention intervention in the world. The need to support human rights and citizenship among people in general and people living with HIV/AIDS in particular, represents the best public health intervention today. The limitations imposed to people with HIV/AIDS deny their rights to access care and prevention, limit the possibilities of providing a safe environment for them and their families, and hinder primary prevention efforts.

Testing and surveillance will only be effective in a safe environment. A call for universal testing for the so called "risk populations" including pregnant women will not be sufficient to halt the epidemic amidst a social environment that stigmatizes and excludes those who will become HIV positive.

Public health officials and governments must directly address stigma as a structural obstacle for ending the epidemic. Besides access to treatment and care, society must guarantee total citizenship and protection against discrimination. The international community has an enormous task in providing a safe environment and opening spaces for solidarity and acceptance for all people living with the HIV no matter their mean of infection. As long as society fosters the intention to deny human rights and full citizenship to a sector of the population on the basis of sexual practices or drug use behavior, stigma and discrimination will prevail.

Challenging HIV-Related Stigma

In order to challenge stigma and its multiple and complex implications we must address it in multifaceted and multilevel perspectives. Link and Phelan (2001) described that it must be multifaceted as to address all possible consequences of stigma, and multilevel because it must address issues of individual and structural discrimination. However, any intervention must address the fundamental cause of stigma, this is the "deeply held attitudes and beliefs of powerful groups that lead to labeling, stereotyping, setting apart, devaluing, and discriminating" (Link & Phelan, 2001, p. 381).

Understanding stigma and discrimination as an exercise of power requires that to change and transform stigma we must challenge the role of such groups in making their beliefs the dominant ones. Issues of heterosexism, morality, class, and exclusion of social sectors from access to work, wealth, and health care must be directly addressed in targeting stigma in general and HIV-related stigma in particular.

We coincide with Castro and Farmer (2005) when they "proposed structural violence as a conceptual framework for understanding AIDS-related stigma" (p. 54). Poverty and racism viewed as structural violence are intricately related to stigma. Poor people are the highest stigmatized group all around the globe, more so for poor people living with HIV/AIDS.

HIV/AIDS stigmatization results in silence, secrecy, lies, and denial (Klitzman & Bayer, 2003) that represent an obstacle for access to care and the possibility of survival for many people living with the infection. Although more than 20 years have passed since the report of the first AIDS case, the studies presented in this special issue clearly demonstrate that stigma is still in the realm of the lives of those more affected by the epidemic. Along with the development of new and better drugs for treatment there is an unavoidable task to overcome discrimination. This should be the agenda for the next decade.

The Content of this Special Issue

It is in light of the difficulties imposed by AIDS stigma that we decided to edit this special issue of the Interamerican Journal of Psychology. The issue is composed by 10 papers from 20 authors from nine countries: Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Argentina, United States of America, Poland, Suriname, Australia and Canada. The issue is divided into three sections that reflect subjects of concern for the authors and areas of potential action.

The first section is entitled The Personal Experience of Stigma: Migration, Co-infection and Everyday Life. In this section we have included papers that evidence through social research the difficulties faced by PLWHA due to the manifestations of AIDS stigma. Several aspects of these manifestations are highlighted in each paper. Irene López Severino and Antonio de Moya contextualize the manifestations of AIDS stigma in the Dominican Republic in relation to migration routes from Haiti to the Dominican Republic. Their paper is an excellent example of the contextual nature of AIDS stigma. As it is combined with other pre-existing stigmas, AIDS stigma is worsened. Such is the case for migrant Haitian communities which are usually blamed for the spread of HIV/AIDS.

The second paper in this section was written by Mario Pecheny, Hernán Manzelli and Daniel Jones from Argentina. They provide us with an interesting analysis related to the hierarchies of meaning associated to different diseases. Although both HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C are stigmatized diseases, the first still evokes more negative interpretations. The authors reflect on the combinations of different types of stigmas in the daily lives of PLWHA and how the transformations in the meanings of other diseases are a potential example for AIDS stigma eradication.

In our third article Mariví Arregui present a compelling look at the everyday manifestation of AIDS stigma in the Dominican Republic. One of the particularities of her paper is that she provides us with an ample range of strategies for stigma eradication, most of which stem from her interviews with PLWHA. Her results evidence how the disease has different meanings for different sectors of the population and how self-hatred can be one of its consequences. She also argues for an approach towards sigma reduction that takes into consideration couples, families, communities, and the church. Although all of these institutions play a role in the stigmatization of HIV/AIDS, Arregui argues for their inclusion in efforts to eradicate it.

In our fourth and final article of this section, Ida Roldán presents us with a compelling look at how culture fosters AIDS stigma among the Puerto Rican community in the United States. She argues that the culture's religious and spiritual roots have pushed HIV/AIDS into the realm of sin. This in turn has disastrous implications for prevention efforts and limits the manifestations of PLWHA.

The second section of the special issue is entitled Facing Stigma in the Health Sector. Although all manifestations of AIDS stigma have negative implications for PLWHA, when it is manifested by health professionals it can be severely worsened since it hinders access to health related services.

In the first article of this section Yamilette Ruiz-Torres, Francheska Cintrón-Bou and Nelson Varas Díaz present data from their study with Puerto Rican health professionals. Their paper examines how AIDS stigma is used as a mechanism of social control over PLWHA. Through AIDS stigma human rights are restricted and the quality of services is severely restricted. Furthermore, surveillance and restriction of PLWHA is described as a technique used by health professionals to stop the epidemic.

The second article in this section examines stigma among Polish health professionals. Maria Gañczak examined mandatory HIV testing as a manifestation of stigma in Poland. Her results evidenced support for HIV testing of all inpatient admissions in hospitals and pre-surgery testing among both nurses and surgeons. Fear of becoming infected in the workplace is a strong initiator of stigmatizing attitudes, and the presented study evidences the extent to which health professionals will go to feel protected from the disease, and the people who live with it.

In the third and final article of this section Winston Roseval explores manifestations of AIDS stigma among nurses in Suriname. His research shows an interesting trend among these health professionals. Participants tended to share amongst themselves confidential information regarding the serostatus of patients. This of course, is a blatant manifestation of AIDS stigma as confidentiality is breached and the process of sharing negative meanings regarding PLWHA is fostered. Still, these same nurses manifested the need to provide financial assistance and find work for PLWHA. This combination of stigmatizing behaviours and positive attitudes towards the needs of PLWHA is evidence that AIDS stigma can co-exist with more positive perspectives on PLWHA. This can hinder effective interventions to reduce it due to the difficulty entailed in its identification.

The third and final section of the special issue is entitled Research, Social Action, and Intervention: A Potential Agenda and is geared towards the establishment of strategies to understand and eradicate AIDS stigma. Articles in this section address the need for specific social research, structural interventions, and the use of legislation as tools for stigma reduction.

In the first article of this section Charles L. Law, Eden King, Emily Zitek and Michelle R. Hebl explore the future directions that research on AIDS stigma should take. This is done through a review of past research in the United States. They provide excellent examples of how stigma has been studied in the past, while providing guidelines for future efforts. They specifically argue for research that disentangles the stigmas of homosexuality, drug use, and AIDS. Research on the implications of AIDS stigma in the workplace is also identified as an emerging need.

In the second article of this section, Dennis Altman from Australia stresses the importance of structural interventions to reduce AIDS stigma. While honoring Jonathan Mann at the International AIDS Conference held in Bangkok, Thailand during the summer of 2004, Altman critically explores the concept of vulnerability in order to expose how risk behaviors are intimately linked to the environment in which they are manifested. Therefore, structural interventions that take into consideration this context are urgently needed.

In our final article Josephine M. MacIntosh explores the role of legislation in the eradication of AIDS stigma in Canada. She stresses that while the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Canada is relatively low, AIDS stigma is common. She presents the efforts of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network as examples of potential actions to prevent, reduce and eliminate AIDS stigma.

In Conclusion

In this special issue we have aimed to evidence the diversity and similarities that the manifestations of AIDS stigma entail for our countries. We feel that although it is an important step towards reflecting and acting to reduce AIDS stigma, much needs to be done in each of the described scenarios. We hope that the included articles are a stepping stone towards that goal.

Finally, we wish to thank all of the authors that have provided us with their time, ideas, and patience in the editing and publication process of this special issue. They all make important contributions towards the eradication of AIDS stigma.

References

Aggleton, P., Wood, K., Malcolm, A., & Parker, R. (2005). HIV-related stigma, discrimination and human rights violations: Case studies of successful programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

Cáceres, C. (2004). Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS infection among men with have sex with men in Latin America and the Caribbean: Current situation and recommendations for epidemiological surveillance. In C. Caceres, M. Pecheny, & V. Terto (Eds.), AIDS and male-to-male sex in Latin America: Vulnerabilities, strengths, and proposed measures (pp. 23-54). Lima, Perú: Cayetano Heredia University and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. [ Links ]

Castro. A., & Farmer, P. (2005). Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: From anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 53-59. [ Links ]

Duffy, L. (2005). Suffering, shame, and silence: The stigma of HIV/AIDS. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 16, 13-20. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York, USA: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Gómez, C., Mason, B., & Alvarado, N. J. (2005). Culture matters: The roles of race and ethnicity in the sexual lives of HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. In P. N. Halkitis, C. A. Gomez, & R. J. Wolitski (Eds.), HIV+ Sex: The psychological and interpersonal dynamics of HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men's relationships (pp. 87-100). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Klitzman, R., & Bayer, R. (2003). Mortal secrets: Truth and lies in the age of AIDS. Baltimore, USA: The John Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363-385. [ Links ]

Ogden, J., & Nyblade, L. (2005). Common at its core: HIV-related stigma across contexts. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women. [ Links ]

Sontag, S. (2001). Illness as metaphor and AIDS and its metaphors. New York, USA: Picador USA. [ Links ]

UNAIDS. (2005a). AIDS epidemic update: December 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization. [ Links ]

UNAIDS. (2005b). HIV infections rates decreasing in several countries but global numbers of people living with HIV continues to rise. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS Press. [ Links ]

UNAIDS/WHO. (2004). Epidemiological fact sheet on HIV/AIDS and sexually-transmitted diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: Authors. [ Links ]

Valdiserri, R. (2002). HIV stigma: An impediment to public health, Editorials. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 341-342. [ Links ]

Varas-Díaz, N., & Toro-Alfonso, J. (2003). Incarnating stigma: Visual images of the body with HIV/AIDS [59 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 4(3). Available: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-03/3-03varastoro -e.htm [ Links ]

Varas Díaz, N., Toro-Alfonso, J., & Serrano-García, I. (2005). My body, my stigma: Body interpretations in a sample of people living with HIV/AIDS in Puerto Rico. The Qualitative Report, 10(1), 122-142. Retrieved December 12, 2005, from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR0-1/varas diaz.pdf [ Links ]

Nelson Varas Díaz. PhD in social-community psychology and is an Assistant Professor at the University of Puerto Rico's Beatriz Lassalle Graduate School of Social Work. He is the first author of the book entitled "Estigma y diferencia social: VIH/SIDA en Puerto Rico". His research work has been published by professional journals which include: Interamerican Journal of Psychology, Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, Qualitative Health Research, American Journal of Community Psychology, AIDS Education & Prevention, and Qualitative Report, among others. His research interests include social stigma, HIV/AIDS, social policy, research methodology, and the development of identity discourses related to health and illness.

José Toro-Alfonso (Puerto Rico). Clinical psychologists and Associate Professor at the University of Puerto Rico's Psychology Department. He is the Secretary General for the Interamerican Society of Psychology. His research interests include HIV/AIDS prevention, attitudes, stigma, adherence to treatment, social support, social policies, construction of masculinities and homophobia. He has been a consultant for USAID in the Caribbean and Central America. His work has been published in peer reviewed journals, chapters, and books. He has coauthored a book on social difference and stigma.

1 Address: nvaras@rrpac.upr.clu.edu, jtoro@uprrp.edu