Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Interamerican Journal of Psychology

versão impressa ISSN 0034-9690

Interam. j. psychol. v.42 n.2 Porto Alegre ago. 2008

Building bridges between organization development and community psychology: an integrative model for multi-site community-based research

Construyendo puentes entre la psicología organizacional y la psicología comunitaria: modelo integral para una iniciativa investigativa a nivel comunitario

Marizaida Sánchez-CesáreoI,1; Gary W. HarperII; Leah NeubauerII; Doug CellarII; Mimi DollII; Grisel RoblesII; Jason JohnsonII; Audrey BangiII; Jonathan EllenIII

IUniversity of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico

IIDePaul University, Chicago, USA

IIIJohns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA

ABSTRACT

Sub-disciplines of psychology have historically focused on the development and evaluation of interventions addressing social issues. However, little has been published regarding the development and evaluation of organizational structures that successfully support such interventions. By bridging the gap between the fields of community psychology and organization development, organizational structures and processes can be designed to enhance the effectiveness of social change programs. This article describes the interface between these two areas of psychology by presenting an integrative model that combines community psychology principles and values with organization development methodologies. This framework has been used to evaluate the organizational structure of a multi-site community-based research project entitled Connect to Protect (C2P®) aimed at reducing HIV incidence among youth.

Keywords: Evaluation, Organization development, Theoretical model, HIV, Adolescents.

RESUMEN

Varias sub-disciplinas de la psicología se han enfocado en el desarrollo de intervenciones para subsanar los problemas sociales. Sin embargo, se ha publicado poco sobre el desarrollo y evaluación de infraestructuras organizacionales que presten apoyo a dichas intervenciones para que sean exitosas. A través de un vínculo entre la psicología comunitaria y psicología organizacional podemos desarrollar estructuras organizacionales y procesos que incrementen la eficacia de programas de cambio social. Este articulo presenta la conexión entre estas dos áreas de la psicología a través de un modelo integrado que combina los supuestos y valores de la psicología comunitaria con la metodología de la psicología organizacional. Dicho modelo se utilizó para evaluar la estructura organizacional que provee apoyo a Conectar Para Proteger (C2P®); una iniciativa investigativa a nivel comunitaria implantada en múltiples ciudad en los Estados Unidos y Puerto Rico. Cuyo propósito es reducir la incidencia de VIH entre jóvenes.

Palabras clave: Evaluación, Desarrollo organizacional, Modelo teórico, HIV, Adolescentes.

Historically, community psychology has focused on the development, implementation and evaluation of interventions that address social issues. The focus of the field has been on the relationships among the individual, his/her communities and the larger society. These connections often occur through an individual’s involvement within a range of different types of groups and organizations & whether as a recipient of services, as a service deliverer, or as a member of a group or organization. Furthermore, most of the interventions designed to address social issues are delivered through organizational settings, including community-based organizations or government institutions. Community-based organizations face myriad organizational issues related to effective functioning such as understanding the communities in which they are embedded and the people they serve, clarifying the mission and vision of the organization, and translating the guiding principles of the agency/project into organizational structures and processes. Despite the focus on community-based organizations as a vehicle for delivering interventions that address social issues, there has been little published in the community psychology literature regarding the development and evaluation of the organizational structures which support the implementation of such interventions. In addition, scant literature has addressed how these structures can facilitate or hinder the delivery of interventions and their eventual success or failure (Boyd & Angelique, 2002).

Over the years the field of organization development has addressed organizational structure and process issues from a behavioral science perspective. Organization development has been defined as a set of behavioral science-based theories, values, strategies, and techniques aimed at the planned change of the organizational work setting through altering members’ on-the-job behaviors for the purpose of enhancing individual development and improving organizational performance (Porras & Robertson, 1992). The organization development literature can provide community psychologists with insights into the variables that influence the effectiveness of organizational structures and processes. Such variables include organizational design, job design, information systems, human resource systems, work teams, leadership and motivation (Cummings & Worley, 2001; Katz & Kahn, 1978; Porras & Robertson).

Clearly there exists common ground between community psychology and organization development with regard to the emphasis on individual growth and development, yet we have not taken sufficient advantage of the opportunities to create bridges between the two fields. Moreover, both community psychology and organization development focus on ecological/systems level of analyses and share the notion of interdependence among different hierarchical levels of a system (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Cummings & Worley, 2001; Katz & Kahn, 1978; Kelly, 1966; Trickett, 1984).

Given the shared foci between community psychology and organization development, we suggest that community psychologists take greater advantage of the organization development literature when designing and implementing community-based interventions. Organization development literature can serve as a foundation to assess and improve organizational structures and processes that ultimately support the work of both the organizations and the individuals involved in community-based social action interventions (Cummings & Worley, 2001).

The purpose of this article is to more clearly define the interface between community psychology and organization development and articulate how both fields can benefit from a better understanding of each other’s models, theories, values, principles, and methodologies. In addition, a model is presented for how to combine aspects of community psychology and organization development to facilitate multi-site community-based research. The practical implementation of this model is illustrated through describing how it was used to guide the work of the Quality Assurance Team (QAT), which is an evaluation body that conducts continual assessments of the organizational structure and functioning of a large multi-site community-based research project titled Connect To Protect (C2P®).

C2P Project Context & Quality Assurance as Exemplar

Connect To Protect (C2P®) is a research project focused on developing, implementing and evaluating sustainable community mobilization efforts aimed at reducing rates of HIV infection among adolescents between the ages of 12 and 24 in fifteen different communities throughout the continental United States and Puerto Rico. In each of these communities, there is an adolescent medicine physician designated as the site Principal Investigator (PI), one to two social/behavioral science or public health professionals that serve as C2P® coordinators, and 4 to 5 staff members who assist in various ways with the implementation of the project. The C2P® project was developed by the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN), which is funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) with support from three other National Institutes of Health (NIH) institutes.

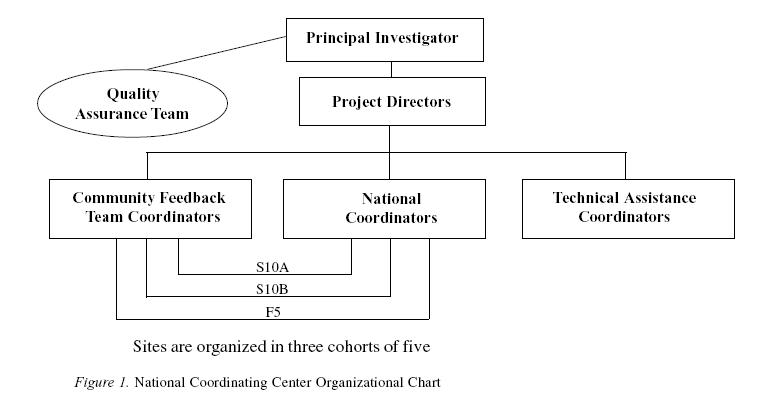

The ATN has created a comprehensive organizational infrastructure to support the success of the 15 local sites in the implementation of C2P® as they strive to include both community agencies and youth in their community mobilization efforts (see Organizational Chart, Figure 1). This infrastructure includes an interdisciplinary team of individuals from the fields of community psychology, applied psychology, adolescent medicine, public health, and communications, and consists of a National Coordinating Center (NCC) that includes: (a) one Principal Investigator (PI) who oversees the project development and direction; (b) two NCC Directors, who are charged with supervising all aspects of the project implementation, as well as managing NCC staff and resources; (c) two National Coordinators, who work directly with the 15 local sites implementing the project and serve as the main conduits for information exchange between the NCC and the site staff, offer on-going guidance, and help to identify and meet/orchestrate site technical assistance and training needs; (d) three Community Feedback Coordinators, who collect and analyze data related to community mobilization and work with the National Coordinators to dispense feedback to sites on how they can improve and/or advance efforts; and (e) two Technical Assistance Coordinators, who provide training and support so various tasks can be accomplished at each of the sites, including geographic information systems mapping, strategic planning meeting facilitation, and intervention training/development.

The Quality Assurance Team (QAT) is an independent evaluation body that conducts continual assessments of the organizational structure and functioning of the overall C2P® project (involving all of the C2P® project members and the NCC members), and is composed of individuals from community psychology, industrial/organizational psychology, and interpersonal communications. The QAT communication and feedback mechanisms provide a preventive function as they identify organizational deficits and strengths and help to correct the obstacles that inhibit effective C2P® functioning. It does this by serving as an autonomous oversight body that continually monitors organizational structure and functioning within the NCC and between the NCC and all 15 sites. The QAT is able to identify potential breakdowns in functioning before they result in negative outcomes and works with all involved parties to rectify these situations (Harper, Bangi & Sánchez- Cesáreo, 2003; Neubauer, Sánchez-Cesáreo & Harper, 2004).

Historically, C2P® is not the first national and multisite research initiative for HIV prevention sponsored at the federal level (Centers for Disease Control AIDS Community Demonstration Project Research Group [CDC], 1999). However, the functions of the QAT, in this context, are unique due to the fact that most multisite national efforts of this nature, such as those sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did not include an organizational evaluation of the national infrastructures providing support to the implementation of the project. Rather we have seen the creation of national evaluation systems that monitor and evaluate the implementation of the programs at the local level and that are coordinated nationally (Chen, 2001). We believe that it is critical to ensure that national infrastructures are developed and evaluated. This type of evaluation will advance the field by developing methodology to evaluate such organizational structures and establishing best practices in the development of organizational structures needed to support a multi-site project.

Integrative Model

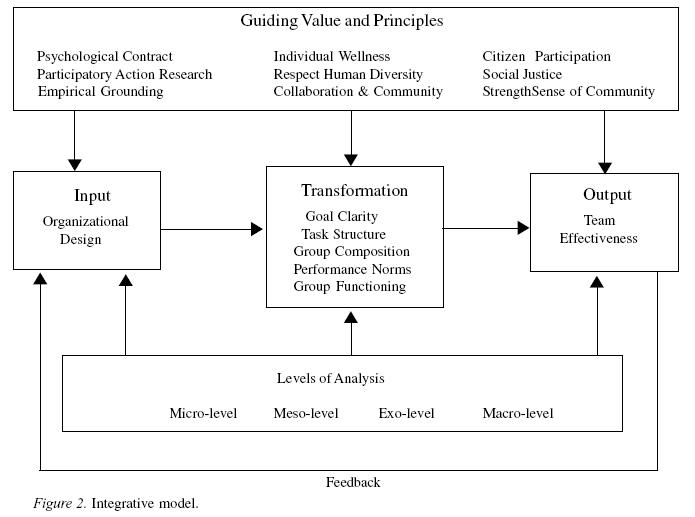

In order to evaluate an organization, such as the C2P® project with its multiple levels and diverse team members, the integrative model employed by the QAT combined theories and values of community psychology with those from organization development (see Integrative Model, Figure 2). This comprehensive model includes values, principles, and theoretical perspectives traditionally considered by both those working in the fields of organization development and community psychology. This combination resulted in a methodological approach that addressed the high levels of integration and coordination required to manage a complex, multi-site organizational structure.

Community psychology and organization development share a focus on ecological/systems level of analysis and the notion of interdependence among different levels of the system (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Cummings & Worley, 2001; Fondacaro & Weinberg, 2002; Katz & Kahn, 1978; Kelly, 1966; Trickett, 1984). The four main components of our integrative model (i.e., theory, methodological approach, feedback and values) span the two fields are explained below.

Theory

The theoretical framework guiding our integrative model is a combination of Ecological Systems Theory of Human Development and Opens Systems Theory. As a field, community psychology is concerned with both micro and macro issues. Therefore, the focus of community psychology is not on the individual or the environment alone, but on the connection and interaction of the two (Dalton, Elias & Wandersman, 2001). One of the main tenets of community psychology is to understand issues from an ecological/systems level of analysis (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Kelly, 1966; Trickett, 1984). In terms of the C2P® project, the QAT was formed to enhance the ATN structures that had been developed to support the 15 local sites in the implementation of a complex community-based project. The structure enhancement focus helps to (a) build relationships with staff members working in diverse community contexts, (b) enhance personal ownership of the project, and (c) improve linkages to the National Coordinating Center (NCC).

Ecological Systems Theory of Human Development

The Ecological Systems Theory of Human Development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) identifies the importance of understanding individuals in relationship to their environment at four levels. The first level, microsystem, is concerned with environments in which the individual engages in direct and personal interaction with others over time. Within the C2P® project we wanted to examine this at two levels. First, we wanted to understand how the relationship between local Principal Investigators (PIs) and Site Coordinators affected the sites’ ability to implement the project. Second, we wanted to see how the relationship across sites influenced their ability to perform locally. At this level we examined the effectiveness of mechanisms set by the NCC to increase communication and support among Site Coordinators. These mechanisms included grouping the fifteen sites in three cohorts of five with their counterparts in other cities.

The second level, mesosystem, is concerned with organizations and their relationships to smaller microsystems and individual members, as well as their relationship with the larger community and society. Within the C2P® project, we wanted to understand the NCC relationship to the local sites and the effectiveness of the guidance provided by NCC to the local sites. The third level, exosystem, is interested in the structures of the larger community, particularly its decision-making, political and business bodies and the way in which those affect and interact with individuals. This is important as individuals participate in the life of their shared locality through community institutions. In this particular project, the ATN represents the exosystem in which the C2P® project is embedded and which influences the ability of local site staff to successfully implement the C2P® project since all major decisions, such as the project’s research focus which impacts the local sites’ future, are made at this level. Finally, the broadest level, macrosystem, includes societies and cultures, as well as governmental and economic institutions beyond the local community. This level may also include regional differences within a national culture, multiple levels of government, and international corporations. The macrosystem of the C2P project is represented by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as the funder for this initiative.

Open Systems Theory

The Open Systems Theory perspective of organizations as comprehensively presented by Katz and Kahn (1978) was also based on a biological metaphor that was very similar to the one used by Bronfenbrenner (1979), as it focuses on describing the systemic nature of organizations. Katz and Kahn emphasized the interrelatedness of the organization and its environment as well as relationships between subsystems that comprise the organization. In recognition of this interdependence between system units, and to enhance organizational effectiveness, models of organizational change have focused on the alignment of the subsystems within an organization and on the alignment of the organization to its environment (Cummings & Worley, 2001; Porras & Robertson, 1992).

Katz and Kahn (1978) considered open systems to be defined by the cyclical pattern of energy transformation necessary for system survival. This transformation process is critical for organizations and highlights the importance of the interrelationships between organizations and the environments where they exchange information and resources. Thus, Open Systems Theory is analogous to the Ecological Model as it emphasizes the interaction between sub-systems, the system, and the environment.

Cummings and Worley (2001) have built on Katz and Kahn’s (1978) model and identified specific inputs, transformations, and outputs at different levels in the hierarchical arrangement that should be aligned in order for the organization to operate effectively. Misalignment, according to this model, would lead to dysfunction for the organization. It is Cummings and Worley’s model of alignments that we have adapted to fit the C2P® project (see Figure 2).

In the case of C2P®, the project is influenced by policies from multiple levels (NIH, ATN, local sites/cities). In addition, this theory postulates that the levels are displayed in a hierarchical order. Each higher level of a system is composed of lower level systems. In the case of C2P®, the project is implemented within the context of the ATN and a local Adolescent Trial unit (ATU), which is typically sponsored by a local university/ government medical center.

The combination of the Ecological Systems Theory and Open Systems Theory helped us develop a comprehensive evaluation approach used by the QAT. The Ecological Model guided the levels of analysis that were investigated, while Open Systems Theory guided the methodological approach to assess multiple levels of a system within an organizational context.

Methodological Approach

In order to evaluate the development of a multi-level organization, our model utilized a methodological approach based on the systems model of alignment presented by Cummings and Worley (2001). The critical level of assessment for our project was what Cummings and Worley termed Group Level Diagnosis. Group Level Diagnosis focuses on evaluating inputs, transformations (design components), and outputs that are necessary in achieving team effectiveness related to performance and quality work life. Therefore, the measure focused on assessing the group level design components of goal clarity, task structure, group composition, team functioning and group norms to ensure alignment with the organizational structure of the larger system in which these work groups were embedded. Thus the inputs, design components (transformations), and outputs at the group level were defined and then assessed in the C2P® project described below.

Inputs

Inputs refer to human and other resources, such as organizational structure and culture, coming into the system. In the case of C2P®, this refers to the human capital created by all the staff at the 15 local ATU and the National Coordinating Center (NCC), which provides support to the local ATUs. Methodological emphasis was given to understanding how the organizational structure of the NCC provided support to each site. We measured this through surveys and interviews conducted with all C2P® staff every six months.

Transformations (Design Components)

Transformations refer to processes that convert inputs into outputs. In organizations, transformations are generally carried out by a production or operation composed of social and technical components. The social component consists of people and their work relationships. Within C2P®, this refers to the work relationships established among local site staff among staff across ATU sites and between local staff and NCC staff. The technological component involves tools, techniques and methods of production or service delivery. In the case of C2P®, this refers to the protocols each local site follows to implement the project and to all the mechanisms and strategies put into place by the NCC to ensure sites have the support to adequately implement the project locally. The evaluation component for transformations focused on assessing five components of the organizational structure: goal clarity, group functioning, performance norms, group composition, and task structure (Cummings & Worley 2001). The purpose of the evaluation was to gain an understanding of how the support mechanisms at the national level assist the functioning on C2P® at the local level.

Output

Outputs are the result of what is transformed by systems and sent into the environment. The successful implementation of the C2P® project and achievement of the outcomes of the project, such as mobilized communities and reduction in HIV incidence and prevalence among youth, reflect our relevant output. In order for the project to be implemented successfully, local sites need to function organizationally well. This is measured by group effectiveness at two levels: (a) performance&which is measured by the group’s ability to successfully increase productivity or improve quality, and (b) quality of work life&which concerns work satisfaction, team cohesion, and organizational commitment.

Feedback

In addition to incorporating the use of group level diagnosis in our model, our framework emphasizes the use of feedback as a mechanism to obtain information regarding the actual performance and results from the system. The internal evaluation system, created by the QAT, utilizes formal and informal feedback and input mechanisms in order to continually monitor the activities of the multi-level C2P® project. QAT members receive information from all members of the project via multiple methods (e.g., surveys, interviews) and then create written reports and memorandums relaying the findings to the entire team. Since the evaluation is focused on continuously monitoring and improving the internal structure and function of the overall C2P® project, the QAT provides preliminary and final findings from the evaluation to the C2P® Protocol Chair, NCC and local site coordinators on an ongoing basis so that potential problems can be addressed on a more immediate basis. This feedback loop has helped to keep the C2P® structure responsive to the evolution of the project.

Guiding Values and Principles

Our integrative model includes values and principles from organization development and community psychology. This was another area where commonalities between the two fields were found. This section will describe how the values and principles fit within our integrative model and how we applied them to the particular context of the C2P® project.

Psychological Contract & Social Justice. The principle of psychological contract within the field of organization development refers to the exchange relationship between the individual employee and the organization. It focuses on the employee’s perception of what s/he will receive in terms of distributive and procedural justice from their employer (Rousseau, 1995). Violations to the psychological contract, in areas such as staff development, compensation, job security, promotion, feedback and interpersonal relationships, will reduce the worker’s trust in the organization and eventually lead to lack of investment, apathy and eventual exit.

A related topic that has been of particular interest recently in the organizational literature concerns the dimensionality and influence of the construct of organizational justice. For example, a meta-analytic review of the literature indicated that there are four factors that comprise the construct of organizational justice: distributive, procedural, informational, and international justice (Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Yee Ng & Porter, 2001). In essence Colquitt et al. concluded that not only are the allocation of outcomes important but so are the processes for determining the allocation, the nature of the information that is presented to members of the organization about the processes, and the interpersonal experience by which such information is communicated for a wide range of organizational variables (performance, satisfaction, commitment, etc.). These findings go hand in hand with the value of social justice presented by community psychology. According to Prilleltensky (Dalton et al., 2001, p. 16) “social justice refers to a fair and equitable allocation of resources, opportunities, obligations, and bargaining power society has as a whole”.

Particularly for this project where people at the local sites were very sensitive to issues related to social justice and where different issues may be salient at different locations, it was particularly important to collect information from the various constituencies and make changes based on this information. Therefore, part of the assessments conducted by the QAT focuses on organizational justice by determining the extent to which staff at the NCC and at each of the 15 sites feel working conditions are just and resources are distributed fairly throughout the system. Additionally, the QAT assesses procedural justice by asking staff to describe their satisfaction with their involvement in the decision making process of the project. The QAT systematically assesses this construct and makes recommendations to revise the C2P project structure in ways that increase the level of distributive and restorative justice experienced by the staff.

Individual Wellness. Individual wellness refers to the physical and psychological health of workers, including personal well-being, development of healthy identity and attainment of personal goals (Dalton et al., 2001). Community psychology has made significant contributions in the development of interventions, social and academic development in children, adolescent behavior and adult health, which focus on this value. However, from an organizational standpoint, the concept of individual wellness has not been studied, particularly regarding the wellness of the employee relative to the conditions of the workplace environment, policies, and procedures. The concept of social-support has been studied and discussed as an important issue in enhancing individual wellness. However, none of these studies have clearly emphasized the application of this value from an organization development perspective or with an interest to develop mechanisms within organizational structures that foster employees’ wellness by honoring their “psychological contracts.”

In the case of C2P®, we have developed mechanisms to provide local site staff with support from their peers (other sites) and from the NCC. Ultimately, the objective is for staff at the fifteen sites to be engaged in the project in a productive and creative way. For this purpose, the QAT assesses the effectiveness of the mechanisms which are currently embedded within the system to foster such values including one-on-one calls (individual calls between the local site staff and the NCC staff on monthly basis), cohort calls (monthly calls are conducted with three groups which included five sites), and remote support (included email, phone and teleconferencing). Furthermore, the Quality Assurance Team has suggested revision of old mechanisms and creation of new ones. The interview process conducted by the QAT every six months has become a support mechanism itself.

Sense of Community. Sense of community refers to the perception of belongingness and mutual commitment, which links individuals in a collective unity (McMillan & Chavis, 1986; Saranson, 1974). Sarason further defined it to include “interdependence with others, a willingness to maintain this interdependence by giving to or doing for others what one expects from them, the feeling that one is part of a larger dependable and stable structure” (p. 157). Historically, community psychology has studied different kinds of communities such as neighborhoods, spiritual communities, and self-help communities (Humphreys & Rappaport, 1994; Zimmerman et al., 1991). Organizations like the ATN can be defined as a community, even though our discipline has not chosen it as frequent unit of analysis. Within the context of our project, the QAT explores the development of sense of community within C2P®, using the multilevel perspective offered by the open system model. The systems perspective, from organization development, was a good fit with this community psychology value as we assess group functioning at different levels in order to assess and intervene if necessary to facilitate the development of group cohesion and productivity. Particularly we examined how members of C2P® at different levels in the structure related to each other interpersonally.

Citizen Participation. This value refers to the peaceful, respectful, collaborative processes of making decisions that allow all members of a community to have meaningful involvement (Wandersman & Florin, 2000). In addition to understanding all the structural supports and systems within the ATN, the QAT intended to influence the system by providing a voice for the C2P® staff on a national level in order to affect the process of developing and further modifying the support systems provided to them by the ATN. This was particularly relevant for this project due to its interdisciplinary nature.

The QAT feedback mechanisms helped to facilitate a collaborative decision-making process across individuals from diverse disciplines and organizational settings by actively involving members from multiple levels within the C2P® project. Unequal power structures can result when working with team members from diverse disciplines and organizational settings, especially in medical settings where hierarchical staff structures are common. The highest educational level obtained by research team members often influences both the level of perceived and actual power in these work settings.

When community-based research involves collaborations with individuals and/or organization from various community settings, the power differential may be compounded. Those without formal training in research may be viewed as less knowledgeable regarding research methodology and may only be given a voice when exploring the community’s views regarding the acceptability and feasibility of community interventions. When these power differentials occur within multi-site community-based research efforts, the voices, experience, and wisdom of all members cannot be fully appreciated and realized. Given this potential for limiting true citizen participation from all involved in the project, the QAT put feedback mechanisms in place that have facilitated the equal sharing of multiple voices and perspectives, and that allows all team members the ability to recommend additional modifications.

Collaboration and Community Strength. This value refers to the relationship between community psychologists and the citizens with whom they work. Some have referred to this value as the most distinctive of our discipline (Dalton et al., 2001). Community psychologists seek to create collaborative relationships in which both the psychologist and the community member contribute knowledge and resources, and in which both participate in the process of setting goals and making decisions (Kelly, 1966; Prilleltensky & Gonick, 1994; Tyler, Pargamet & Gatz, 1983). For the community psychologist, creating of an egalitarian partnership becomes a desired outcome of all endeavors. In the case of C2P, the QAT holds this value at the core of its beliefs. The QAT advocates for organizational structures and mechanisms which foster an egalitarian relationship within the leadership structures of the National Coordinating Center. Given the fact that C2P® is a national project with a decentralized structure, as each of the 15 sites has its own highly qualified C2P® staff, it is crucial for those local staff to be empowered and trusted in the process of implementing the C2P® project. If the concept of community mobilization that C2P® attempts to embrace is to be successful at the local level, sites must establish a mutual relationship with their community partners, and emulate a similar model with their community partners. Finally, the NCC, in turn needs to model the same with C2P® staff at the 15 sites.

Respect for Human Diversity. This value recognizes and prizes the variety of communities and social identities, based on gender, ethnic and racial membership, sexual orientation, ability or disability, socioeconomic status, age, or other terms (Trickett, Watts & Briman, 1994). This value is very much interrelated to those mentioned above. Given the interdisciplinary nature of the C2P® staff, and the diversity of the group by gender, sexual orientation, professional experience, ethnicity, language, region and age, the QAT recognizes the importance of ensuring that the structure of the project be culturally competent rather than just culturally sensitive. In this context, competence refers to the integration and transformation of knowledge about individuals and groups of people into specific standards, policies, practices, and attitudes used in an organizational setting to increase the effectiveness of the work environment; thereby producing better outcomes. Cultural competence calls for a level of value instituzionalization which would not be present if only cultural sensitivity (awareness) is achieved.

Empirical Grounding. A very important goal in the field of community psychology is the relevance and practicality of bringing about social change. Since its origins, our discipline has sought to strike a balance between research and practice. Community psychologists strive to define and address community problems and issues, in ways that can be studied in research. According to Dalton et al. (2001, p. 19) “Community psychologists are impatient both with theory that lacks empirical basis in community life and with research that ignores the context and interest of the community in which it occurs”. In this respect, the QAT is invested in a balance between research and practice. The QAT makes its recommendations based on data analysis that uses information triangulation. Also the QAT is invested in the applicability that our findings have in changing and enhancing the organizational structures, which support C2P® on both local and national levels. If this organizational structure is functional and supportive of the local staff, that in turn will assist to catalyze community mobilization at the various cities to reduce HIV incidence among youth.

Participatory Action Research. Community psychology has a strong focus on participation and action. As in many instances, the researchers are also members of the community or group being studied. As a discipline, community psychology places emphasis on the involvement of participants with all aspects of the research, including development of the research questions, methods, instruments and interpretation of the data. Community psychology is interested in promoting positive changes as a result of its research, thus, applicability beyond issue description and understanding is central to the field. Both of these values were applied to our work as the QAT in collaboration with the NCC and C2P® local site staff developed the evaluation questions and mechanisms for interpretation of the results of our assessment. Furthermore, mechanisms to develop solutions and recommend changes to the NCC organizational structure to continue to foster support for local site staff in implementing the C2P® project were created.

Conclusion

The constant assessment and change management process provided by the QAT using our integrative model has played a crucial role in ensuring the C2P® project was implemented with the support of a solid organizational infrastructure both at the national and local level. Based on our experience with the C2P® project, it seems worthwhile to invest in a body such as the QAT to constantly monitor those organizational factors that might facilitate or hinder the implementation of a large scale multi-site project. By recognizing and capitalizing on the commonalities that exist between the community psychology Ecological Model and the organization development Open Systems Theory based model of change, this body addressed the organizational challenges associated with large multi-site projects. It is recommended that the knowledge acquired from this study be used along with the existing behavioral science literature base to improve the organizational structures and processes that support the implementation of prevention programs and other initiatives.

The models and methods that guide organizational analysis and change should be included in the approaches and practices used by community psychologists for community-based program development and program evaluation. The systematic assessment of organizational variables affords the opportunity to identify problems and dysfunction within organizations and to design and implement corrective measures in order to ensure effective functioning of work teams. In order for community psychologists to do this we need to review our training curricula to include classes on organization development and we need to foster more interdisciplinary collaborations where community psychologists can work hand in hand with experts in organization development. We ought to continue building bridges between community psychology, organization development, and other fields in order to further theory building and practice.

References

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Boyd, N. M., & Angelique, H. (2002). Rekindling the discourse: Organization studies in community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(4), 325-348. [ Links ]

Chen, H. T. (2001). Development of a National Evaluation System to Evaluate CDC-Funded Health Department HIV Program. American Journal of Evaluation, 22(1), 55-70. [ Links ]

Centers for Disease Control AIDS Community Demonstration Project Research Group (1999). Community-Level HIV Intervention in 5 Cities: Final Outcome Date From the CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 336- 345. [ Links ]

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Yee Ng, K., & Porter, O. L. H. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425-445. [ Links ]

Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (2001). Organizational development and change (6th ed.). Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College. [ Links ]

Dalton, J. H., Elias, M. J., & Wandersman, A. (2001). Community psychology: Linking individuals and communities. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Fondacaro, M. R., & Weinberg, D. (2002). Conceptes of social justice in community psychology: Toward a social ecological epistemology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(4), 473-492. [ Links ]

Harper, G. W., Bangi, A., & Sánchez-Cesáreo, M. (2003). Internal Assessment of the Connect To Protect Project. Report prepared for the C2P National Coordinating Center of the Adolescent Trial Network, National Institute of Health. [ Links ]

Humphreys, K., & Rappaport, J. (1994). Researching self-help/mutual aid groups and organizations: Many roads, one journey, Applied and Preventive Psychology, 48, 892-901. [ Links ]

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Kelly, J. G. (1966). Ecological constraints on mental health services. American Psychologist, 21(6), 535-539. [ Links ]

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: Definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6-23. [ Links ]

Neubauer, L. C., Sánchez-Cesáreo, M., & Harper, G. W. (2004). Internal Process Evaluation of the Connect to Protect Project. Report prepared for the C2P National Coordinating Center of the Adolescent Trial Network, National Institute of Health. [ Links ]

Porras, J. I., & Robertson, P. J. (1992). Organizational development: Theory, practice and research. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 719-822). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [ Links ]

Prilleltensky, I., & Gonick, L. (1994). The discourse of oppression in the social sciences: Past, present, and future. In E. J. Trickett, R. J. Watts, & D. Birman (Eds.), Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context (pp. 145-177). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Saranson, S. B. (1974). The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Trickett, E. J. (1984). Towards a distinctive community psychology: An ecological metaphor for the conduct of community research and the nature of training. American Journal of Community Psychology, 12, 261-279. [ Links ]

Trickett, E, J., Watts, R. J., & Briman, D. (Eds.). (1994). Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Tyler, F. Pargament, K., & Gatz, M. (1983). The resource collaborator role: A model for interactions involving psychologists. American Psychologist, 38, 388-398. [ Links ]

Wandersman, A., & Florin, P. (2000). Citizen participation and community organizations. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 247-272). New York: Plenum. [ Links ]

Zimmerman, M. A., Reischl, T. M., Seidman, E., Rappaport, J., Toro, P. A., & Salem, D. A. (1991). Expansion strategies of a mutual help organization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 19, 251-278. [ Links ]

Received 22/12/2006

Accepted 06/06/2008

Marizaida Sánchez-Cesáreo & University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Gary W. Harper, Leah Neubauer, Doug Cellar, Mimi Doll, Grisel Robles, Jason Johnson, Audrey Bangi & DePaul University, Chicago, USA

Jonathan Ellen & Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA

1 Address: University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus, Graduate School of Public Health, Center for Evaluation and Sociomedical Research, PO BOX 365067, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 00936-5067. Telephone: 787.758.2525 xt.1031 or xt.1422.

E-mail: marisanchez@rcm.upr.edu