Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Journal of Human Growth and Development

versão impressa ISSN 0104-1282versão On-line ISSN 2175-3598

J. Hum. Growth Dev. vol.29 no.2 São Paulo maio/ago. 2019

https://doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.v29.9421

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Cross Cultural adaptation into Brazilian Portuguese language of Derriford Appearance Scale 24 (DAS-24) for people living with HIV/AIDS

Marcos Alberto MartinsI, II; Angela Nogueira NevesIII; Timothy MossIV; Walter Henrique MartinsV; Gerson Vilhena PereiraVI; Karina Viviani de Oliveira PessôaVII; Mariliza Henrique da SilvaVIII; Luiz Carlos de AbreuI

ILaboratório de Delineamento de Estudos e Escrita Científica. Centro Universitário Saúde ABC, Santo André, SP, Brasil

IIServiço de Cirurgia Plástica do Hospital Samaritano de São Paulo, SP, Brasil

IIIEscola de Educação Física do Exército

IVUniversity of the West of England

VProfessor Assistente do Centro Universitário Saúde ABC, Santo André, SP, Brasil

VIGerson Vilhena Pereira, Professor Titular do Centro Universitário de Saúde ABC

VIIPrograma Municipal de IST/AIDS e Hepatites Virais de São Bernardo do Campo, São Paulo, Brasil

VIIIPrograma Estadual de IST/AIDS de São Paulo. Brasil

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Body image can be defined as the representation of beliefs, emotions and perceptions about the body itself, manifested in behaviors directed to the body. When the body changes because of a disease and does not seem healthy, the self-concept may be severely challenged. People living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) are particularly vulnerable to the distress and psychosocial impact of appearance, but in Brazil the assessment of those body image changes was subjective because there was not an available scale in Brazilian Portuguese to assess body image changes in clinical practice or research.

OBJECTIVE: To carry out the cross-cultural adaptation to the Brazilian Portuguese of the Derriford Appearance Scale 24 (DAS-24), with the verification of the linguistic, semantic, conceptual and cultural equivalence of the people living with HIV/AIDS in Brazil

METHODS: We followed the five stages of culturally sensitive translation: direct translations, synthesis of translations, back-translations, expert committee meeting and pre-tests. The process of cultural adaptation was presented in a descriptive and analytical way, following patterns of methodological studies. The minimum, maximum and median values of the responses of each item were calculated from the pool of data from the third pretest group of 50 participants. The median of the item scores, the correlation on each item with the total score and the internal reliability, were calculated using the Cronbach alpha test.

RESULTS: The analysis of the responses of the last pre-test group indicated that attention must be given to items A, H, T and V in a future psychometric study. The present study is not enough for this scale to be used in clinical practice. To ensure that the culturally adapted instrument generates valid and reliable data, a subsequent study investigating its psychometric properties should be conducted.

CONCLUSION: The cross-cultural adaptation of the Derriford Appearance Scale 24 (DAS-24) in its components of linguistic, semantic, conceptual and cultural equivalence to Brazilian Portuguese for the population of people living with HIV/AIDS was fully carried out. Despite this achievement, it is emphasized that the use of the Brazilian version of DAS-24 in research and clinical routine is advised only after a psychometric study with this instrument.

Keywords: Body Image. Appearance. HIV. AIDS. Psychometry.

Authors summary

Why was this study done?

People living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) are a population especially vulnerable when it comes to distress and the psychosocial impact of appearance, because in addition to having to live with the virus infection, they also have to deal with the stigma of the disease, revealed by the bodily changes that can be caused by lipodystrophy.

The evaluation of these body image changes was subjective and depended on the opinion of the infectious disease physician who decided whether or not this patient should be indicated for possible treatment of these changes in their appearance.

There is a need for an outcome measure that allows researchers to investigate processes and contribute to and improve appearance problems, so it is crucial to have a measurement that is psychometrically sound, derived from clinical experience and easy to apply and score. The literature review indicated that there was no scale to evaluate image changes available for clinical use or for research in Brazil.

What did the researchers do and find?

Derriford Appearance Scale 24 (DAS-24) is a scale that allows you to evaluate underlying processes that soften or emphasize problems with appearance. Unlike other distress measures regarding appearance in the body image area.

This study performed the translation and cultural adaptation of Derriford Appearance Scale 24 (DAS-24), originally from the United Kingdom, into Brazilian Portuguese, with semantic, conceptual, cultural and idiomatic equivalence, through methodology that followed the guideline of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons / Institute of Work and Health (AAOS / IWH) (BEATON et al., 2002).

The process of cultural adaptation was presented descriptively and analytically, following standards of methodological studies. The minimum, maximum and median response values of each item were calculated from the data pool of the third pre-test group of 50 participants.

At the conclusion of the cultural adaptation study, for preliminary verification of the quality of the items, the median of the item scores, the correlation of each item with the total scale score and the internal reliability were calculated using Cronbach's alpha test.

What do these findings mean?

This is the first culturally adapted scale for Brazil designed to assess discomfort and distress regarding appearance changes with the primary target audience of people living with HIV/AIDS (PWHA), and may extend care to this vulnerable population.

The significance of this research shows to be a pioneer in adapting the scale to the cultural aspects of Brazil, aimed at assessing discomfort and distress in relation to appearance changes having as primary target audience people living with HIV / AIDS (PLWHA). expand assistance to this vulnerable population.

Although thorough and carefully conducted, the present study is not yet sufficient for this scale to be employed in clinical practice. To ensure that the culturally adapted instrument generates valid and reliable data, a subsequent study investigating its psychometric properties should be performed.

INTRODUCTION

According to the cognitive behavioral perspective, body image can be defined as the representation of beliefs, emotions and perceptions about the body itself, manifested in behaviors directed to the body. It is a multidimensional construct, which comprises both lived perceptions and attitudes about the body that, in turn, is subdivided into an evaluative dimension and an investment dimension1. From this schematic processing behaviors and emotions about the body emerge2. Finally, in this perspective, the appearance and function of the body play a fundamental role in the self-concept, which is permeated by the individual's cultural values and bodily experiences3.

Some aspects of physical appearance are better accepted and valued than others. Those who meet the social standards of the body, based on distinct attributes and behaviors that qualify as adequate or ideal tend to be better accepted4. People who do not have these characteristics are stigmatized by their "deviation" and are subject to social exclusion and other forms of discrimination, causing "distress" in relation to the body5.

Previous studies had correlated body distress negatively with quality of life6,7 and positively with depression, anxiety, shame, dissatisfaction with the body, fear of negative evaluation about the body7-9. It is emphasized that this discomfort or "distress" in relation to appearance is not correlated with the size, location or severity of the appearance characteristic in non-conformity with the social pattern or the subject's desire10. It is worth emphasizing that the subjective experience with the appearance may be more challenging than the objective reality in itself1.

When the body changes as a consequence of a disease or does not seem healthy, the self-concept can be severely challenged11. Thus, the body image of people with disabilities or with chronic diseases or with changes in appearance is modeled by perceptions that emerge from this special social context, because they arouse extraordinary reactions in social relations and in the concept of oneself12,13. When there is a negative reaction to these visible changes, especially external reactions from social contact, there is a measurable increase in "distress" and discomfort in relation to appearance in the individual, which can have a profound and lasting psychosocial impact14. However, it is essential to recognize that this does not always happen because some people live well with their differences in appearance and these differences are subjectively assessed as less important in life as a whole, and less emotionally provocative15.

People living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) are particularly vulnerable to "distress" and the psychosocial impact of appearance on changes caused by lipodystrophy. Lipodystrophy syndrome refers to metabolic complications and alterations in the distribution of adipose tissue, where fat loss occurs in peripheral regions (face, arms, legs and buttocks) and accumulation of fat in the central region (abdomen, dorsocervical spine, breasts) associated with to several factors, such as the action of the virus, genetics16 and High Power Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART)17. In addition to having to deal with the changes experienced in their bodies, they also need to deal with the stigma of the disease, revealed by these modifications18-20.

The visibility of HIV is associated with a greater perception of stigma, social rejection, guilt and shame21-23. Facial lipodystrophy is the most frequent24 and is associated with depressive states and low self-confidence25,26, with a feeling of lack of control over the body26, of the impossibility of denial of HIV27, with an impact on financial life, social relations and a love relationship28. Fear of changes in appearance, particularly lipodystrophy, is a common reason for the discontinuation of medications, thus increasing the risk of developing AIDS29.

However, the patient's ability to re-signify his or her life in this scenario must not be underestimated30. A way back to development with posttraumatic growth is a real possibility. Hence, evaluation and constant monitoring of discomfort and dysphoria in relation to appearance - including to identify protective factors and predictors of distress - are necessary, allowing better addressed in clinical practice

Among the instruments for evaluating distress and discomfort in relation to the body, we highlight the Derriford Appearance Scale 24 (DAS-24)31, which allows us to evaluate underlying processes that soften or emphasize problems with appearance. The DAS-24 items were created from the patients' experiences and the psychometric investigations, which generated data in clinical and non-clinical samples32. Differing from other measures of distress in relation to appearance in the body image area, DAS-24 does not focus only on the issue of body mass and does not emphasize eating disorders and associated disorders. These characteristics make the DAS-24 an instrument potentially relevant to clinical practice, in which the evaluation of distress in relation to appearance may be an important variable in the decision-making.

In this perspective, the aim of this research was to carry-out the cross-cultural adaptation to the Brazilian Portuguese of the DAS-24, with the verification of the linguistic, semantic, conceptual and cultural equivalence for people living with HIV/AIDS.

METHODS

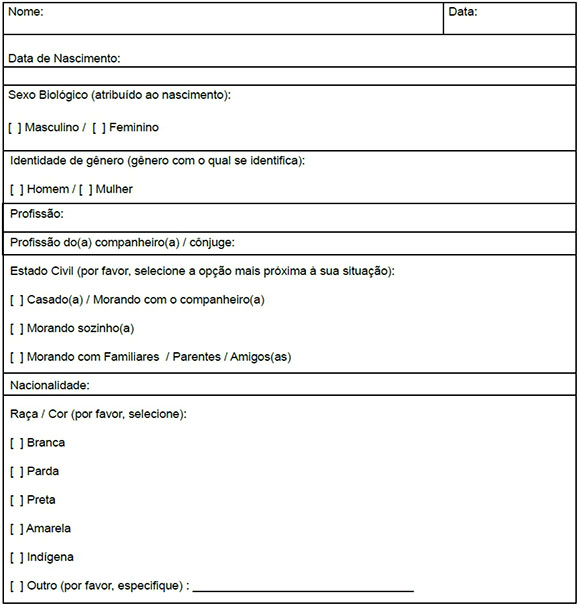

Methodological study, which deals with the cultural adaptation of measurement scale by theory, approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Faculdade de Medicina do ABC (ABC Medical School) and is registered under number 923.269.

Instrument

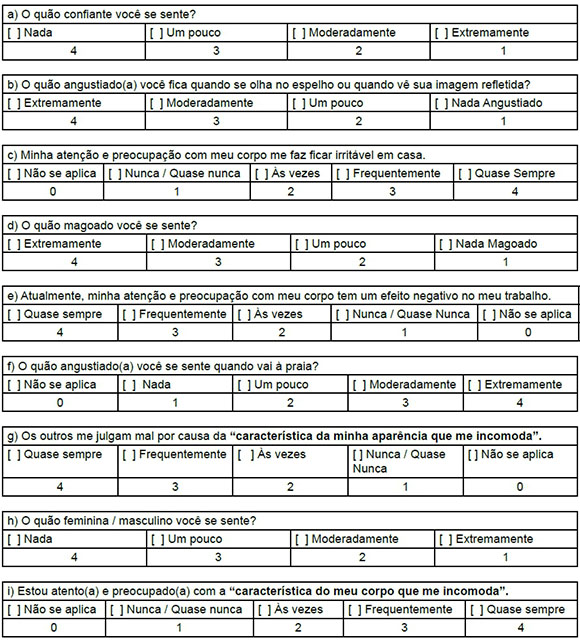

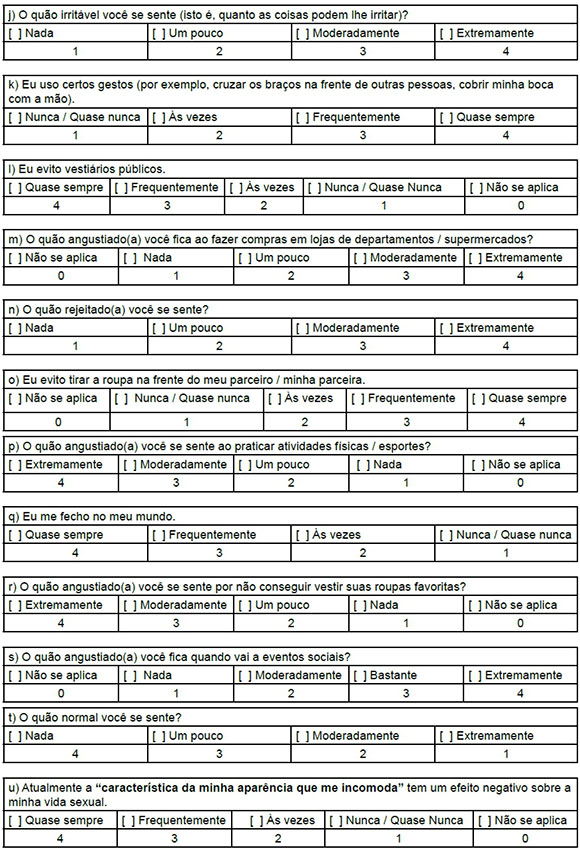

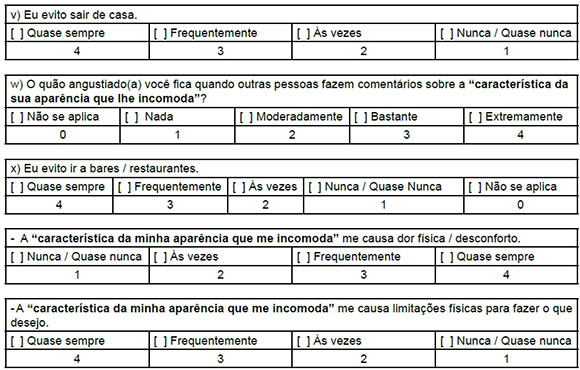

The Derriford Appearance Scale-24 (DAS-24)31. The DAS-24, original from United Kingdom, was created to evaluate the distress and difficulties experienced in people living with problems of appearance31. Items A, H and T are arranged in a Likert scale of four points (4= not at all, 3= a little, 2= moderately, 1= extremely). Items B, D, J and N are arranged in a Likert scale of four points (1= not at all, 2= a little, 3= moderately, 4= extremely) as well as questions F, M, P, R, S and W in which adds the "not applicable" option (0 = not applicable, 1= not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately, 4 = extremely). The items K, Q and V are arranged in a Likert scale of four points (1 = never/almost never, 2= sometimes, 3= often , 4 = almost always) and items C, E, G, I, L, O, U and X on a Likert scale of five points (0 = not applicable, 1 = never/almost never, 2 = sometimes 3 = often, 4 = almost always). There are also two additional elements which are not identified with letters, they are not included in the structural model nor in the sum of the score, but which provide information about the intensity of pain and the frequency of physical limitations that the respondent may have due to their altered appearance (Table 1) The higher the score, the greater the anguish and the concern about the appearance.

Methodological Procedures

Initially, it was asked to the author of the of Derriford Appearance Scale-24 (DAS-24), authorization for the use of this instrument and for its cultural adaptation to Brazilian Portuguese. Next, the guideline for the cross-cultural adaptation process recommended by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons and Institute of Work and Health (AAOS/IWH)33 was chosen for conducting this research.

The AAOS/IWH guideline recommends five steps to implement the process of cultural adaptation of scales: (I) independent translations; (II) synthesis of translations; (III) backtranslations of the synthesis; (IV) committee of experts reunion and (V) pre-test33. For this last step, specifically, our methodological references were also Malhotra34 and Reynolds et al.35.

To carry out the first step, two Brazilians with fluency in English performed translations independently, one of them with knowledge of the subject (body image) and another with total lack of it, in order to provide greater reliability to the theoretical components and linguistic aspects of the DAS-24 scale.

In the second phase, a third person fluent in English language synthesized translations (T1, T2). This third person is as a "judge or mediator", who solves discrepancies and drafted a synthesis version in Portuguese denominate T12.

In the third phase, two native English-speaking with fluency in Portuguese from Brazil received the synthesis version (T12). They performed the back-translations (BT1 and BT2) independently and without knowledge of the original version of the instrument.

Next, an expert committee consisting of two translators, the mediator or "judge", the two retro translators, a methodologist and three health professionals (who worked directly with the population of interest). The members of the committee of experts had previously received the original scale, the all versions produced (T1, T2, T12, BT1, BT2, comments and questions) and an evaluation sheet. Initially, the experts analyzed the questions in DAS-24 synthesis version individually, analyzing the equivalence between the original instrument and the translated one in four areas: semantic, experimental or cultural, idiomatic and conceptual equivalence. They must evaluate as follows: (-1) is not equivalent - and a new version has been suggested by the experts; (0) indicated the scale item was adequate; and (1) indicated lot - which indicated total adherence to the concept, i.e., equivalence. In the following week after receiving the material, the meeting of the expert committee was held and the collective discussion started with the lowest average items. Considerations on questions and instructions were only terminated when, after reformulated, the equivalences were between 0 and 1. This meeting lasted approximately two hours and from the items accepted and reformulated by the experts resulted the pre-test version.

Pre-test

A sample of the target population was required to perform the fourth step of the research, the pre-test. The selection of this sample was non-probabilistic33, we looked for individuals that could give us answers that generated more coherent data for the research34. Participants included in the study met the following criteria: being over 18 years of age, being seroreagents for HIV and being on medication.

To implement the first pre-test phase, two groups of five people were recruited according to recommendations for the pre-test of Malhotra34 and Reynolds et al.35. Each questionnaire was applied individually, in the office, without time limitation. After completing the instrument, the researcher interviewed each participant asking about the difficulties of filling the questionnaire, clarity of items, adequacy of questions related the purpose of evaluation, adequacy of items to the population of interest. After these first two groups, on which a qualitative analyses were the main focus, a final version of the scale was obtained and applied in a group with 50 participants following the recommendations of Beaton et al.33 for a quantitative analysis of the responses. All responses were recorded on a specific form.

Data Analysis

The process of cultural adaptation of DAS-24 for PLHA was presented in a descriptive and analytical way, following the pattern of studies used. For a preliminary empirical analysis, which allows us to identify problems with items37, the minimum, maximum and median values of the responses of each item were calculated from the data pool of the third group of 50 participants. Items that show a wide variety of distribution and those that discriminate different points along a continuum are items that are free of bias or social desirability38,39.

The correlation of each item with the total scale score and the internal reliability was calculated through the Cronbach alpha test. Items with low correlation (<0.50)39 are indicative of being excessively difficult, or easy or ambiguous, or unrelated to the latent variable40. Items whose elimination increase the value of Cronbach's alpha test indicate that they are problematic for the internal coherence of the instrument40. These data are preliminary indicators of the quality of items.

RESULTS

Translation, Synthesis and Back-translation

Comparing instructions and DAS-24 items, there were eight items equivalents between the T1 and T2 translations. The others were very close, but the synthesis written with nine items as suggested by T1, with three as suggested by T2 and five items were reformulated. Furthermore, the introductory part of DAS-24 was considered, in which six parts were for synthesis as suggested by T2, one as suggested by T1 and one was reformulated for synthesis.

The major challenges in these early stages were two expressions that caused translation difficulties as follows: "self-conscious" / "self-consciousness" and "feature", which appear several times and are key words for understanding the scale.

In relation to the expression "self-conscious"/ "self-consciousness", the difficulty was to find a single word that could translate this expression and could theoretically be conceived as the perceptions, thoughts, memories, projects and actions that express the permanence and coherence of the ego and hence of the human person41.

This expression is present in the introductory part of DAS-24 in the section of the instructions for filling the questionnaire: "The first part of the scale is designed to find out if you are sensitive or self-conscious about any aspect of your appearance (even if this is not usually visible to others). One of the translators translated "self-conscious" / "self-consciousness" as "autoconsciente" (self-conscious) and the other translator as consciente (conscious). However, neither of the two translation options seemed to correspond to the meaning the author intended to give the sentence and the issue was brought to the attention of a third person (a mediator). The mediator, in turn, resorted to the Portuguese version of DAS-24 translated into Portuguese from Portugal42, for which the terms "desconfortável ou constrangido" were used. It was decided "to draw attention to onself and maintain this negative cognitive aspect", captured this concept best, suggesting for the synthesis the word "atento" (no sentido de preocupado) / "attentive (in the sense of concerned) as translation for "self-conscious".

The term "atento" (no sentido de preocupado) was used both in the introduction, and in items C, E and I. In back-translation, the term "self-conscious" was not employed, one of the retro-translators translating the synthesis into "sensitive or aware" (in the sense of concerned) and the other to "attentive" (in the sense of worried).

The difficulty with the word "feature" was not idiomatic, but semantic and conceptual. The concern stemmed from the fact that in the initial part of the DAS-24 the respondent needs to enunciate the part(s) of appearance that causes discomfort. Then, a new instruction appears: "From now on, we will refer to this aspect of your appearance as your feature". Thus, it was necessary that this part of the body identified as causing of discomfort was well defined so as not to cause errors or misunderstandings in the choice of responses throughout the rest of the instrument. One of the translators translated "feature" as "condição" and the other translator as "característica" (which was also the option used in the version from Portugal). After discussion with the expert who has the role of "judge", the need for improvement of this translation was identified so that it would be very clear to anyone to answer the scale what was the true meaning of this "characteristic".

So, to translate the word feature, this expression was created: "a característica da minha aparência que me incomoda", which was back-transtated as: "aspect of your appearance that bothers you" and "characteristic of your appearance that bothers you".

Of the twenty-four questions and the two additional ones, the back-translations BT1 and BT2 were identical in 14 items, with minor differences in the rest of the items. In relation to the original scale, seven items were identical in the two back-translations. The biggest differences were due to the choice of synthesis for "feature" e "self-consciousness" / "self-conscious".

At the end of these processes of translation, synthesis and back-translation, the material was further analysed by the author (Timothy Moss) of the DAS-24 for additional feedback from BT1 and BT2. It was noticed that in most of the items obtained adequate backtranslation in BT1 or BT2. However, Dr. Moss recommended reviewing the translation of "self-consciousness", as "autoconsciência" (self-consciousness) conceptually, that is, the sense of self-consciousness (the direction of attention for himself), but also has an emotional component around constraint/discomfort, which had not been grasped.

In respect of item "G", "Other people mis-judge me because of my feature", he said that "misjudge" makes more sense that other people are making inaccurate judgments, but it does not mean that they are making critical judgments. Finally, in item "C", "My self-consciousness makes me irritable at home", he pointed out that in the two back-translations "irritable" was written as "irritated" and that irritated is different from irritable. There is a very subtle difference between "being angry" instead of "getting angry". Irritable is the general approach that can lead to being irritated. All these comments were included in the documents of the Committee of Experts to be considered.

Expert's Committee

At the meeting of expert committee, again, the words "self-conscious" and "self-consciousness" deserved a wide discussion. Its literal translation would be "autoconsciente". However, there was a risk of generating different interpretations for the same item, creating a lack of conceptual equivalence, which could be fundamentally different among the participants.

Taking into account the considerations previously made by Dr. Moss, we resorted to the psychology's dictionary of the American Psychological Association (APA) psychology dictionary43. In it, "self-consciousness" is defined as:

1. a personality trait associated with the tendency to reflect on or think about oneself. Psychological use of the term (e.g., in personality measures) refers to individual differences in self-reflection, not to embarrassment or awkwardness;

2. Some researchers have distinguished between two varieties of self-consciousness: (a) private self-consciousness, or the degree to which people think about private, internal aspects of themselves (e.g., their thoughts, motives, and feelings) that are not directly open to observation by others; and (b) public self-consciousness, or the degree to which people think about public, external aspects of themselves (e.g., their physical appearance, mannerisms, and overt behavior) that can be observed by others.

3. extreme sensitivity about one's behavior, appearance, or other attributes and excessive concern about the impression one makes on others, which may lead to embarrassment or awkwardness in the presence of others. - self-conscious adj.

According to these definitions, the experts agreed that here the suggestion: "atento (no sentido de preocupado)", with emphasis in parentheses, would be appropriate, since it captured the essence of being self-conscious.

The alternative created for the translation of "feature" in the synthesis of translations was also ratified by the committee of experts. They considered it is important to have the clarity of what this characteristic is defined in the introductory part of the DAS-24, because it will be the reference for the answers of the other 24 items of the scale. The word "característica" alone did not seem to reinforce the need for the respondent to always remember that this was the reference for their answers. After extensive discussion, the experts agreed to adapt this translation to "característica da aparência que lhe incomoda". This strategy sought to keep clear to the respondent of DAS-24 on what he should keep in mind. It was evaluated that this solution would maintain the conceptual equivalence in relation to the original instrument, also ensuring the semantic and cultural equivalence.

Discussions on the terms "self-consciousness" and "feature" dominated the analysis of the introductory part of the DAS-24. Questions C, E, G, U and W plus the two additional questions have also been modified to take account of the above mentioned considerations about these terms. In relation to the other elements A, B, D, F, L, M, N, R, S, T, V and X were considered conceptual, idiomatic, semantic and culturally equivalent to the original.

Items K and P were adjusted to ensure cultural equivalence. In item K "I adopt certain gestures...", it was added the act of covering the mouth with the hand to the examples previously described in the question, because this is a common gesture used to disguise possible deformities in this area and added meaning to this question. In item P, "How distressed do you get while playing sports/games?", the word "games" was changed to "atividades físicas" (physical activities), which makes more sense in our environment and to the population for which the instrument was prepared.

In item G, "Other people misjudge me.", in addition to the adequacy of the word "feature", there was a discussion by the experts on how best to maintain the semantic equivalence of the word "misjudge", if the best translation would be "mal juízo" or "me julgam mal". The experts agreed that the second option was better, corroborating with what had already been advised by Dr. Moss. Still seeking compliance with the guidelines given by Dr. Moss, item J, "How irritable do you feel?", was carefully analyzed. The experts concluded that the literal translation could be misunderstood and suggested adding information in parentheses that could facilitate the respondent's understanding and thus the final version was: "O quão irritável você se sente (isto é, quanto as coisas podem lhe irritar)?", to rightly point out the differences highlighted in the earlier observations made by Dr. Moss.

In item B, "How distressed do you get when you look yourself in the mirror/window?", the expression "window" was suppressed by a cultural question: this seemed to be an unusual situation, which could lead to confusion in the moment of responding. In order to attain cultural equivalence, only the alternative of looking his mirrored image was retained.

In relation to the idiomatic equivalence, the item Q, "I close into my shell", deserved attention. The idiomatic expression illustrates social isolation behavior, in which the respondents should assess how much they had maintained within their comfort zone. The experts agreed that the best translation for this idiom would be: "Eu me fecho no meu mundo" ("I close myself in my world").

Unlike the English language, in the Portuguese language there is a need for differentiation between male and female. To meet this, need the experts agreed to use gender bending in the adjectives and nouns of observable variables. An example of this procedure can be given with the semantic change of item O, "I avoid getting undressed in front of my partner", for which the experts agreed to put the alternatives "meu parceiro" / "minha parceira".

Finally, Dr. Moss was returned to the results of the expert meeting and asked for his assessment, especially on the choice made for the translation of "self-consciousness" / "self-conscious". He responded by acknowledging that the term is a difficult concept to address and that similar difficulties have occurred in other cultural adaptations. He also said that there are translation options that are close enough, and that under the APA framework a good proposal has been made, thus giving his approval, not only for this, but for the other items as well. After its endorsement, the meeting of experts was considered closed and the produced version was taken to the pre-test.

Pre-test

Two groups of five patients each from a São Bernardo do Campo HIV/AIDS outpatient clinic were recruited and also, they were asked their opinion on the next items: response options, comprehension of the instructions, adequacy of the layout and congruence between the desired response and the indicated answer.

The first group consisted of 4 men and 1 woman, with a mean age of 56.5 ± 8, 26 years (Min = 47, Max = 60 years). These participants provided some ideas to improve the scale.

The first point of attention was the introduction. Three of the five participants reported some difficulty to understand the purpose of the questionnaire. These doubts were taken to the methodologist expert and after some discussions the following change to the second pre-test was proposed: "This questionnaire refers to how you feel about your appearance. This FIRST PART is designed to find out if you are worried or bothered about any characteristic of your appearance (even if it is not normally visible to others)".

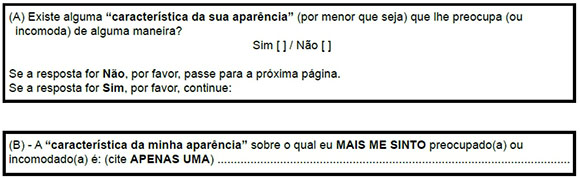

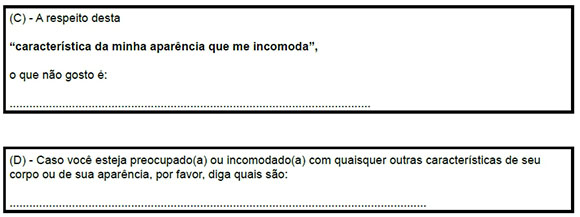

There was another occurrence in the first pre-test. It was noted that in the field for the answer to the question (B) "característica da minha aparência" sobre o qual eu mais me sinto preocupado(a) ou incomodado(a) é: (The "characteristic of my appearance" about I most feel troubled or uncomfortable is:), in the introductory part, two participants put more than one characteristic that bothered them, before realizing that there would be another field that would give them an opportunity to write other answers.

The problem was not due to difficulty of understanding, but because there was no previous reading of the questions that would follow. It was not though to be an obstacle to the interpretation of the answers, on the contrary it was conceived to provide clarity to the respondent. Thus, together with the methodologist, this point was discussed again, proposing the following reformulation for the second pre-test: (B) A "característica da minha aparência" sobre o qual eu MAIS ME SINTO preocupado(a) ou incomodado(a) é: (cite APENAS UMA):" ["(B) The" characteristic of my appearance "about which i feel MOST worried or uncomfortable is: (quote ONLY ONE):"].

It was unanimous the difficulty of the participants in understanding the difference between the alternatives "never/almost never" and "N/A (not applicable)" in the answers of items C, E, G, I, L, O, T and X. They did not realize the difference between these alternatives, for example: "If I never do, therefore, the question is not applicable". Faced with this impasse, Dr. Moss was contacted and asked about the possibility of eliminating the N/A alternative from these items, without this interfering with the score of these answers. Dr. Moss argued that "there is a subtle difference between "not applicable" and "never/almost never". It's a pretty subtle difference and psychometry works with punctuation as it is! In view of its positioning, the N/A option was maintained in these questions, but in agreement with methodologist, instead of using the abbreviated form (N/A), the phrase "Não se aplica" ("Not applicable") was used, in full. It was also proposed the alteration of formatting and diagramming of the scale, where the answers were arranged separately, within tables, and together with each one of the answers was placed the corresponding numeral value (attachment 1).

With these changes, a new group of 5 respondents, all males, aged between 46 and 61 years, mean age of 52.75 ± 6.65 years, were recruited. The same procedures adopted in the first pre-test were repeated. In the interview following the completion of the DAS-24, it was verified that no difficulty in understanding was reported, the layout of the scale was approved, the possibilities of response were judged appropriate as well as the pertinence of the items to be assessed and the population target. It was concluded that the changes greatly helped the clarity and understanding on the part of the respondents.

To be even more certain that the work done had produced an adequate and clear Portuguese version, a third group of 50 participants, of whom 31 were men, were recruited. The mean age of this group was 41.84 ± 11.80 years, ranging from 23 to 75 years (Table 1).

With the exception of items G and K, which did not have answers at the maximum value of the scale, all other items varied among all possibilities of response of the Likert scale, indicating that it was possible to assure all possible answers. The median of the minority of items - A, B, D, I, J, Q, R, T and W - was coincident with the median of the response scale. For the other items, the median was lower, indicating low frequency or low concordance to the observable variable.

To check if this concentration of the item responses could cause systematic errors, either because the items are poorly written, confusing or that lead the respondent to social desirability, we verified if their elimination increased the value of the instrument's Cronbach's alpha test, α = 0.94, it was confirmed that the value didn't increase.

Finally, we analyzed the results of the correlation score total-item. The values indicate that moderate correlations (>0.50 - <0.80) occurred in 20 of the 24 items and in the two extra items and weak correlations in item A (0.39), item H (0.26), item T (0.46) and item V (0.47).

DISCUSSION

The process of cross-cultural adaptation followed strictly the methodological procedures of the chosen references33 going through all the stages. We consider that the two changes of this guide, the inclusion of the original author of DAS-24 to the process and the modifications done in the pre-test groups, were positive aspects.

Recruiting small groups as recommended by Malhotra34 and Reynolds et al.35 provided more detailed information about the layout of the material; the participant's understanding of the questions and answers of each item; the adequacy of the answers indicated on the paper with acceptable responses. Annotating all the information in detail ensured not miss important information that could indicate problems in answering the questionnaire. These procedures, in small groups, become more feasible in terms of time and quality of interview depth. Returning to the field after adjustments is another direction of methodological conduct suggested by these authors, which then allows to verify if the changes made were in fact pertinent and if the problems were solved. This return is not predicted in Beaton et al.33, but in this research it was assessed as relevant and valid to ensure understanding of instructions and items, and that no further changes were needed. This procedural change in the pre-test is not new and has been tried on other occasions44.

Dr. Moss's comments and his answers to specific questions greatly contributed to achieving, especially, the idiomatic and conceptual equivalences of the items. In addition, in sharing the experiences and difficulties of the other cultural adaptations already made with the DAS-24 in Taiwan45 and Portugal42 we could have an extended view of the interpretations of each observable variable (item). The inclusion of the original author of the instrument in the cross-cultural adaptation process had already been tested46 and it was considered a positive procedural aspect in this process.

It is important to point out that the Brazilian version presents some differences in relation to that of Portugal, especially as regards how the translation of "feature" and "self-consciousness" / "self-conscious" was treated. But in addition, there are differences in other items, especially in the verbal tense and in the idiomatic expressions, which in fact reflects the differences of the two Portuguese language variations spoken among these countries. The reflection is that this fact reinforces the need to adapt transculturally the instruments to the target country that is intended to be used in the future, since only a translation could not understand the cultural and linguistic variations of the observable variables47, running the risk of generating distorted interpretations of the latent variables under evaluation.

The analysis of the median score of items as well as their maximum and minimum values gives a view of the tendency of response to observable variables. It is important to point out that with the exception of two items, G and K, the items obtained all the possible answers, demonstrating that there was no bias in the answers. Although not always the median of some items was close to center point of the scale (which would indicate a balanced distribution of the answers) we could verify that the withdrawal of any item would not increase the value of the Cronbach alpha test, excluding, a priori, evidence that some items might be inadequate. A future psychometric study should also observe items A and H, since they had a correlation with the total score, which may indicate low adherence to the latent variable under analysis.

It is important to say that, although meticulous and carefully conducted, the present study is not yet enough for this scale to be used in clinical practice. To ensure that the culturally adapted instrument generates valid and reliable data, a subsequent study investigating its psychometric properties should be conducted.

Another limitation would be the focus given to the target population of PLHA, always taking them into account in the analysis of the items. However, having this instrument available for psychometric validation saves Brazilian researchers time and resource, since the process of cultural adaptation can be financially costly and take months. To the researcher interested in validating the DAS-24 for use in research with other samples, we recommend contacting the principal researcher to have access to the generated documentation, retake the pre-test in their population of interest, and see if something needs to be adjusted.

CONCLUSION

In view of the results the results generated, we conclude that the cultural adaptation of the DAS-24 to Brazilian Portuguese, with the primary target audience being people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA).

REFERENCES

1.Cash TF. Cognitive-Behavioral perspectives on body image. In: Cash TF, Smolak L. Body image: a handbook of science, practice, and prevention. New York: Guilford Press, 2011; p. 39-47. [ Links ]

2.Cash T. Cognitive-Behavioral perspectives on body image. In: Cash T. Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance. V.1. Elsevier, 2012; p.334-42. [ Links ]

3.Cash TF. The Body Image workbook: an 8-step program for learning to like your looks. New York: The Guilford Press, 2000. [ Links ]

4.Mauss M. As técnicas corporais. In: Mauss M. Sociologia e antropologia. São Paulo: EPU; EDUSP, 1974. [ Links ]

5.Puhl RM, Peterson JL. Physcial appearance and stigma. In: Cash TF. Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance. Academic Press, 2012; p.588-94. [ Links ]

6.Katre C, Johnson IA, Humphris GM, Lowe D, Rogers SN. Assessment of problems with appearance, following surgery for oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer using the University of Washington appearance domain and the Derriford appearance scale. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(10):927-34. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.12.006 [ Links ]

7.Moreira H, Canavarro MC. The association between self-consciousness about appearance and psychological adjustment among newly diagnosed breast cancer patients and survivors: the moderating role of appearance investment. Body Image. 2012;9(2):209-15. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.11.003 [ Links ]

8.Moreira H, Canavarro MC. A longitudinal study about the body image and psychosocial adjustment of breast cancer patients during the course of the disease. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(4):263-70. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2010.04.001 [ Links ]

9.Merz EL, Kwakkenbos L, Carrier ME, Gholizadeh S, Mills SD, Fox RS, et al. Factor structure and convergent validity of the Derriford Appearance Scale-24 using standard scoring versus treating 'not applicable' responses as missing data: a Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network (SPIN) cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e018641. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018641 [ Links ]

10.Moss TP, Rosser BA. The moderated relationship of appearance valence on appearance self consciousness: development and testing of new measures of appearance schema components. PloS One. 2012;7(11):e50605. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050605 [ Links ]

11.Lupton D. Medicine as culture: Illness, disease and the body. Los Angeles: Sage, 2012. [ Links ]

12.Tavares MCGF. Imagem corporal: conceito e desenvolvimento. Barueri: Manole, 2003. [ Links ]

13.Schilder PA. Imagem do corpo: as energias construtivas da Psiquê. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1980. [ Links ]

14.Williamson H. The psychosocial impact of being a young person with an unusual appearance. J Aesthetic Nurs. 2014;3(4):186-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/joan.2014.3.4.186 [ Links ]

15.Harcourt D, Rumsey N. Body Image and Biomedical Interventions for Disfiguring Conditions. In: Cash TF, Smolak L. Body Image: a handbook of science, practice and prevention. 2 ed. New York: Guilford Press, 2011; p.404-14. [ Links ]

16.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Manual de tratamento da lipoatrofia facial: recomendações para o preenchimento facial com polimetilmetacrilato em portadores de HIV/AIDS. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2009. [ Links ]

17.Hoffmann C, Rockstroh JK. HIV 2015/2016. Medizin Fokus Verlag, 2015. [cited 2019 Feb 27] Available from: https://www.hivbook.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/hiv-2015-16-complete-1.pdf. [ Links ]

18.Alexias G, Savvakis M, StratopoulouΙ. Embodiment and biographical disruption in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). AIDS Care. 2016;28(5):585-90. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2015.1119782 [ Links ]

19.Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):225-36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032705 [ Links ]

20.Kumar S, Samaras K. The Impact of Weight Gain During HIV Treatment on Risk of Pre-diabetes, Diabetes Mellitus, Cardiovascular Disease, and Mortality. Front Endocrinol. 2018; 9:705. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00705 [ Links ]

21.Brener L, Callander D, Slavin S, Wit J. Experiences of HIV stigma: the role of visible symptoms, HIV centrality and community attachment for people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2013;25(9):1166-73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.752784 [ Links ]

22.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):87-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120802032627 [ Links ]

23.Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(9):1823-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006 [ Links ]

24. Leclercq P, Goujard C, Duracinsky M, Allaert F, L'henaff M, Hellet M, et al. High prevalence and impact on the quality of life of facial lipoatrophy and other abnormalities in fat tissue distribution in HIV-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(5):761-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2012.0214 [ Links ]

25.Cofrancesco J Jr, Brown T, Martins CR. Management options for facial lipoatrophy. AIDS Read. 2004;14(12):639-40. [ Links ]

26.Tate H, George R. The effect of weight loss on body image in HIV-positive gay men. AIDS Care. 2001;13(2):163-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120020027323 [ Links ]

27.Reynolds N, Diamantopoulos A, Schiegelmilch B. Pretesting in questionnaire desing: a review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Int J Market Res. 1993;35(2): 171-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/147078539303500202 [ Links ]

28.Abel G, Thompson L. "I don't want to look like an AIDS victim": A New Zealand case study of facial lipoatrophy. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(1):41-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12459 [ Links ]

29.Williamson H, Wallace M. When treatment affects appearance. In: Runsey N, Harcour D. The Oxford handbook of the psychology of appearance. Reino Unido: Oxford University Press, 2012; p.414-38. [ Links ]

30.Rzeszutek M, Gruszczyńska E. Posttraumatic growth among people living with HIV: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2018;114:81-91. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.006 [ Links ]

31.Carr T, Moss T, Harris D. The DAS24: A short form of the Derriford Appearance Scale DAS59 to measure individual responses to living with problems of appearance. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10(Pt 2):285-98. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1348/135910705X27613 [ Links ]

32.Campana ANNB, Tavares MCGCF. Avaliação da imagem corporal: Instrumentos e diretrizes para a pesquisa. São Paulo: Phorte, 2009. [ Links ]

33.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Recommendations for the Cross-Cultural adaptation of Healthy Status Measures. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Institute for Work & Health, 1998. [ Links ]

34.Malhotra NK. Pesquisa de marketing: uma orientação aplicada. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2008. [ Links ]

35.Reynolds NR, Neidig JL, Wu AW, Gifford AL, Holmes WC. Balancing disfigurement and fear of disease progression: patient perceptions of HIV body fat redistribution. Aids Care. 2006;18(7):663-673. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0954012050028705 [ Links ]

36.Zangirolami-Raimundo J, Echeimberg JO, Leone C. Research methodology topics: Cross-sectional studies. J Hum Growth Dev. 2018;28(3):356-360. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.152198 [ Links ]

37.DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. 2 ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2003. [ Links ]

38.Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol Assessment. 1995;7(3):309-19. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309 [ Links ]

39.Hair JR, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Análise Multivariada de Dados. 6.ed. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2009. [ Links ]

40.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994. [ Links ]

41.Zeman AZ, Grayling AC, Cowey A. Contemporary theories of consciousness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62(6):549-552. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.62.6.549 [ Links ]

42.Moreira H, Canavarro MC. The Portuguese version of the Derriford Appearance Scale - 24. Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, Coimbra, Portugal: 2007. [ Links ]

43.VandenBos GR. APA Dictionary of psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2007. [ Links ]

44.Ferreira L, Neves AN, Campana MB, Tavares MCGCF. Guia da AAOS/IWH: sugestões para adaptação transcultural de escalas. Aval Psicol. 2014;13(3):457-61. [ Links ]

45.Moss TP, Lawson V, Liu CY. The Taiwanese Derriford Appearance Scale: The translation and validation of a scale to measure individual responses to living with problems of appearance. Psych J. 2015;4(3):138-45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.91 [ Links ]

46.Sousa P, Gaspar P, Fonseca H, Hendricks C, Murdaugh C. Health promoting behaviors in adolescence: validation of the Portuguese version of the Adolescent Lifestyle Profile. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91(4):358-65. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2014.09.005 [ Links ]

47.Khalaila R. Translation of questionnaires into arabic in cross-cultural research: techniques and equivalence issues. J Transcult Nurs. 2013;24(4):363-70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659613493440 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

drmam@uol.com.br

Manuscript received: October 2018

Manuscript accepted: January 2019

Version of record online: October 2019

THE DERRIFORD APPEARANCE SCALE (DAS 24) - BRASIL

Esta PRIMEIRA PARTE foi desenvolvida para descobrir se você está preocupado(a) ou incomodado(a) sobre qualquer característica da sua aparência (mesmo que não esteja normalmente visível para os outros).

De agora em diante, nós iremos nos referir a esta característica da sua aparência como a:

"CARACTERÍSTICA DA SUA APARÊNCIA QUE LHE INCOMODA".

SEGUNDA PARTE

Instruções:

- As perguntas a seguir são sobre a forma como você se sente ou age.

- Elas são simples. Por favor, selecione a resposta que se aplica a você.

- Se as alternativas de resposta não se aplicam a você de forma alguma, selecione a opção de "Não se Aplica".

- Não gaste muito tempo em nenhuma das questões.