Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1414-6975versão On-line ISSN 2175-3520

Psicol. educ. no.48 São Paulo jan./jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.5935/2175-3520.20190006

ARTIGOS

Changing the meaning of the images in the history textbook: an indication of internal colonialism

Mudando o significado das imagens no livro de história: uma indicação do colonialismo interno

Cambiar el significado de las imágenes en el libro de texto de la historia: una indicación del colonialismo interno

City University of New York Estados Unidos da América do Norte Master of Liberal Arts

ABSTRACT

The Indian history textbook for class eight published by the National Council for Educational Research and Training includes a plethora of images, and readers are encouraged to look at them critically. There is a clear effort to teach history through the visuals. This research is primarily concerned about the representation of the historical stories of the tribal people of India and thus it only closely analyzes the chapter four that is dedicated to the stories of the tribal people. Moreover, this paper critically examines three pictures of the tribal people of India, taken by an internationally recognized photo journalist Sunil Janah, that have been attached to the forth chapter of the book. This is an effort to show the contrast between the stories behind the pictures in their original context, with the new stories that the same pictures depict in a very different context in the textbook. The changed meaning of the pictures and the way they are used in the textbook shows an ignorance of telling the history of the tribal people in their own way. A closer look will reveal the dominance of highly colonized ideology that encourages the book writers to dehumanize a very diverse Indian tribal community and neglect their identity by putting them under one umbrella term. Also, the same ideology reflects when the book attempts to tell their stories in an apathetic and monotonous way.

Keywords: History textbook; Images; Indian tribe; changing meaning; colonized mentality; Dehumanisation.

RESUMO

O livro de história indiano para a classe oito publicada pelo Conselho Nacional de pesquisa educacional e formação inclui uma infinidade de imagens, e os leitores são encorajados a olhar para estas criticamente. Há um esforço claro em ensinar a história através do visual. Esta pesquisa é principalmente preocupada com a representação das estórias históricas do povo tribal da Índia e, para tanto, analisa detalhadamente em seu capítulo quatro as histórias do povo tribal. Além disso, este artigo examina criticamente três fotos do povo tribal da Índia, tiradas por um jornalista fotográfico internacionalmente reconhecido, Sunil Janah, que foram anexadas ao capítulo quatro do livro. Este é um esforço para mostrar o contraste entre as histórias por trás das imagens em seu contexto original, com as novas histórias que as mesmas imagens retratam em um contexto muito diferente no livro didático. O significado alterado das imagens e a maneira como elas são usados no livro didático, mostra uma ignorância em contar a história das pessoas tribais em sua própria maneira. Um olhar mais atento revelará a predominância da ideologia altamente colonizada que incentiva os escritores do livro a desumanizar uma comunidade tribal indiana muito diversa e a negligenciar sua identidade ao colocá-la embaixo de um guarda-chuva de um só termo. Além disso, a mesma ideologia se revela quando o livro tenta contar suas histórias de uma forma apática e monótona.

Palavras-chave: livro de história; mentalidade colonizada; desumanização.

RESUMEN

El libro de texto de historia de la India para la clase ocho publicado por el Consejo Nacional de Investigación y Capacitación Educativa incluye una gran cantidad de imágenes, y se anima a los lectores a mirarlas críticamente. Hay un claro esfuerzo por enseñar a la historia a través de las imágenes. Esta investigación es principalmente preocupante de la representación de las historias históricas del pueblo tribal de la India y por lo tanto sólo analiza de cerca el capítulo cuatro que está dedicado a las historias del pueblo tribal. Además, este documento examina críticamente tres imágenes del pueblo tribal de la India, tomadas por un periodista fotográfico reconocido internacionalmente, Sunil Janah, que se han adjuntado al capítulo cuatro del libro. Este es un esfuerzo para mostrar el contraste entre las historias detrás de las imágenes en su contexto original, con las nuevas historias que las mismas imágenes representan en un contexto muy diferente en el libro de texto. El significado cambiado de las imágenes y la forma en que se utilizan en el libro de texto, muestran una ignorancia de contar la historia del pueblo tribal a su manera. Una mirada más cercana revelará el dominio de la ideología altamente colonizada que alienta a los escritores de libros a deshumanizar a una comunidad tribal india muy diversa y descuidar su identidad poniéndolos bajo un término general. Además, la misma ideología se refleja cuando el libro intenta contar sus historias de una manera apática y monótona.

Palavras-chave: libro de Historia; mentalidad colonizada; deshumanización.

INTRODUCTION

"Our Past-III, part I" begins with critically questioning the history that was told in Indian classrooms before the writing of the book. It explicitly points the finger to British historians for bringing in the western viewpoint of looking at Indian history. The first chapter of the book shows how Indian history became a showcase for the victory of the colonizers and "their activities, policies, achievements" (OUR PASTS - III , Part I, 2017, p. 3). Therefore, the dates when the rulers won a war or achieved success was given priority in history. On the other hand, the textbook suggests seeing the same history from a different angle. It advocates for a change of telling historical tales where history needs to be told not from the dominant's (i.e., rulers/kings) perspective but rather from the other perspective. As a result, the emphasis has been shifted from remembering dates of the special occasions of the king's life to the stories of the people whose life have changed over time. Therefore, a period in history is more important than dates here. The book stresses on asking historical questions as it is a better way to learn the history of our seemingly mundane life experiences. It encourages readers to find the past of their present life by asking critical historical questions. More importantly, the book unequivocally advocates for describing historical narratives and looking at the world from an unconventional vantage point. Here, the writers are eloquent about the fact that the same historical story can change if it is seen from different viewpoints.

The book is very vocal about the possible damage of seeing Indian history through colonial lenses. Consequently, it wants to avoid any chance of seeing the historical events from a western perspective by primarily getting rid of British historian's perspective to tell Indian history. However, it fails to consider the possible presence of colonial mentality that Indian themselves may have inside them. It is very difficult for Indians, who have been colonized for centuries together and have been gone through the very educational system that has been designed by the colonizers (Nurullah & Naik, 1948). The research is intended to unveil the hidden colonized mentality inside the bookmakers and their ideology that played a pivotal role to developing the history textbook by closely examining the images of the tribal people attached to the textbook.

The history textbook for class eight includes a plethora of images, and readers are encouraged to look at them critically. Throughout the book, there is also an effort to teach history through the visuals. Therefore, each picture in the book has been chosen carefully and attached to a particular place on a page to serve a purpose. The fourth chapter of the history textbook that dedicates itself to the history of the tribal people has included pictures taken by famous photographers like Sunil Janah, Tiziana and Gianni Baldizzone. These are globally renowned photographers who are known for their work on tribal peoples across different parts of India.

In this paper, I am going to critically analyze three images that are used in chapter four to describe the tribal peoples of India. To provide a little bit of background on these pictures, they were originally taken by the famed photojournalist and documentarian Sunil Janah. He has published the photos in his book "The tribals of India" and has narrated the history behind each of the pictures portrayed in this book. In this article, I will elucidate the difference between the message that the photographer has tried to convey to us through the photos and the message that the very same pictures appear to give in chapter four of the textbook. I will first depict the story that Sunil Janah delineates while introducing the pictures to readers of his original book. Then, I will carefully analyze chapter four of the textbook to see the purpose of attaching these three photographs and how their usage in a different context have changed their meaning. Because as Tejeda et al. indicated "meanings are never neutral; they are always situated socially, culturally, and historically, and they operate within the logic of differing ideologies that imply differing sets of social practice" (Tejeda & Espinoza). Finally, I will examine the ideology of the textbook committee members that have been reflected through the selection of the pictures and attaching them in a particular place that might be responsible for changing its meaning entirely.

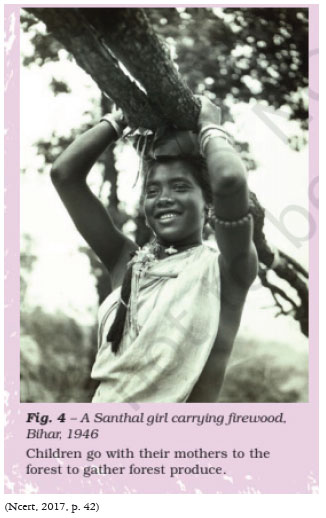

The most beautiful girl of the village

I will start my discussion with the picture of a pretty Santal girl who is carrying woods on her head. She is nicely dressed up and has a beautiful smile on her face. Her hair is nicely done, and she has flowers attached to her hair that enhances her beauty. Additionally, she is wearing bangles, nose ring, earrings, and necklaces. Sunil Janah has placed the picture in the first section of his book where he talks about the tribal communities who live in the border area of Bihar, Orissa and West Bengal, the three states of eastern India. He has named the picture as "The most beautiful girl of the village" (Janah, 1993, pp. 18-19) and the picture occupies a whole page in his book. Although he has attached the picture at the beginning of the chapter, he talks about the girl and how her pictures have been taken almost at the end of the chapter. The construction of this portion of the book shows that the girl and her story have a special place in the chapter. The picture of the girl has been carefully laid out at the beginning to captivate the reader's attention and hopes to take the curious reader on a journey where they would be looking for her story till the end.

"The Tribals of India" embodies the personal experiences of Sunil Janah and tries to encapsulate the journey of taking the photos that are a vital part of his book. In the first segment of the book he describes the tribal people and the reasons for his presence amongst them. In a few paragraphs, he beautifully articulates his experience of staying with the tribal people and how he took the photographs. He talks about Chotaramu Murmu, an old but very active and physically strong man of the Santal village who took him to places to take the photos. They visited few places, and during that time, the author experienced a few glances of different aspects of their life. After going through a brief history of the tribal community and their culture, poetry, songs, and dance, Sunil Janah started talking about the "red mahua wine" and how the government exploits the love of the tribal people for it. The government forbids the Santals to make red mahua wine and sells them a white adulterated version which can be poisonous. He goes on to say how tribal people are compelled to pay a bribe to police officers to buy the wine they like. Chotaramu was very fond of red mahua wine and, thus, asked for a helping of wine at every house they went to. After having red mahua wine, they were walking through paddy-fields to capture the harvesting activities. As penned in the book, the old man noticed that the young photographer was more interested in taking pictures of the women, so he suggested the photographer that he must take pictures of the most beautiful girl in the village. Sunil Janah noticed that none of the girls in the group that he was shooting at the moment showed resentment on hearing this. They instead agreed with the old man that she was the most beautiful girl in the village. Somewhat to his surprise, Sunil Janah found that the girls rather encouraged him to go with the old man and click her pictures before the sun went down. The old man said:

"If you want to photograph our prettiest girl, don't waste too much of your time here. She is in the forest cutting wood. You will make me a sad man if you go away without taking photograph of her...The following morning, I found that Chotaramu had detained her and her equally lovely sister, a child in her early teens, to be photographed again, lest their beauty which he took such a grandfatherly pride in, went unrevealed to the world" (Janah, 1993, p. 26)

Therefore, the picture not only describes the beauty of the girl herself, but it also shows the beauty of the relationship that the Santal peoples have with each other. It shows the generosity of the Santal women who not only firmly agreed with the old man's claim but also went ahead and motivated the young photographer to take her picture. The pride of the old man who recommended her name and brought her and her sister the next morning for more photograph indicated a beautiful bonding between the houses in the Santal community. Therefore, the picture is not limited to the beauty of the girl but also tells a charming story of the honesty among tribal men and women that made the piece of art possible. In other words, the beauty of the girl is a reflection of sheer love and care that her community shows for her. Consequently, it is a common sense that a person who is a part of a society that is rooted firmly in mutual relation, cannot be seen as just an individual. Therefore, the western ideology that prefers individual over group can only distort the meaning and undermine the beauty of the image.

On the other hand, the book attached the picture on a page that is talking about the division of labor in a tribal community. In this chapter, the book is describing Baiga men and women who live in the central part of the country, but it attaches a picture of the Santal girl whose life is very different from the former community (Janah, 1993). For example, apart from their culture, their skill sets are also different. While the former are great hunters, the latter tribal community are sedentary and cultivators. Thus, it is evident that the chapter does not consider the differences amongst the tribal peoples in India and tries to bring them under one umbrella term.

The sentence is written just under the picture, saying "Children go with their mothers to the forest to gather forest produce" supports the fact that chapter four of the history textbook uses this picture to show that it is prevalent for tribal children to go with their mother and help them to collect woods. As the textbook does not describe the nature of tribal society and culture and the disparity between them and the mainstream Indian culture, this picture might blur the line between tribal children and the child labor in India. This picture, with the caption attached to it, implies that the girl is delighted to collect woods with her mother in a forest. Even worse, using the picture out of its context gives a different meaning that implies every child in India who does menial labor is as happy as the girl in the picture. It is a reflection of a western white male ideology that made the writers adhere to the picture on this page of the chapter showing children are happy while they are doing menial work. The usage of this picture in this part of the textbook is an effort of dehumanizing the tribal peoples as well as the working-class children because the textbook uses an image of a girl from a completely different society and changes its meaning by generalization.

Also, it was the day of the festival, and that is why the girl is nicely dressed up. She is probably helping her family to collect forest produces for the festival. Moreover, she is posing for a picture, and thus, she puts a beautiful smile on her face. It is not that she was smiling while she was cutting trees and collecting woods in the forest. Importantly, there is a difference between tribal children working with their family and other poor children who work as a laborer. Santals, like many tribal peoples, do their work for themselves, and they produce products together for their use. They make everything they might need for living. Therefore, all of them are equipped with many different skills, unlike the modern market global economy where everyone has a particular skill and exchange their skills with money to buy other stuff that they need for living.

If somebody has an expertise in something, then he or she will invest their skill and time for everyone in the village one by one. For example, the chapter talks about an artist who gets a few days off from his regular community work, to show his talent by drawing pictures on the walls of all the huts of the village one after another. He is rewarded not by money but by food and drinks. Santal peoples "will appreciate the work of art and reminisce, 'our Munshi Tudu did that!. What greater reward is there for an artist !" Therefore, the works that Santal men, women, or children do are very different from the work of a laborer or a factory worker or any other menial work done by a person in an individualistic society. Unlike such a society which is influenced by the western lifestyle, the tribal people live their life with utter joy. Because

perhaps one of the reasons for the spontaneous joy of life in the tribals as compared to the other morose Indian villagers, is that they never have to feel smaller than others in their communities; they do not judge people in terms of "success" or caste. (Janah, 1993, p. 13)

Moreover, the work done by the people for their community or themselves cannot be equated with the work done by the wage earners. While in the community, people produce goods for their use, the wage earners produce extra products for the company. Therefore, while the former has the right to the goods they have produced together, the latter cannot claim the additional products they have made outside the money that they are given. It is important to note here that the tribal peoples of India are living a life akin to the communist ideology way before the idea of communism emerged in Europe (Roy, 2012). Consequently, this paper is not trying to advocate for the communist ideology inspired way of life but rather attempted to describe a way of life that was common in ancient history all over the world. The modern world failed to spread its tentacles amongst the tribal people because they lived in somewhat geographical isolation in the interior part of a forest but still enjoyed a happier life (Janah, 1993). Hence, their way of life cannot be compared with the majority of Indians who are strongly influenced by the western way of living.

Importantly, the definition of children might not be the same for Santal peoples as the western society that the Indian government follows. According to the government of India, any person under 14 years of age is considered as a child, which follows the definition given by the UN (UNICEF, 2011). The government defines childhood in order to either provide them with mandatory education, healthcare, or defend them from any criminal offense. On the other hand, the tribal community that have their own rules and a set of rituals they follow for marriage and other social activities are unlikely to be applicable for the definition given by the government of India. So, the girls who were helping their community for living and went to collect woods may not be considered as a child in her society. As a result, it is evident now that the usage of the picture out of context reflects an ideology of the writers that is highly influenced by the western ideology that impede their vision to cultural differences. A reflection of internal colonialism is vivid in the ideology of the book writers who are unable to differentiate the culture and way of living of the tribal peoples from the mainstream Indians. By mentioning internal colonialism, I am referring the definition given by Barrera, and cited in Tejeda et al. where internal colonialism is stated as a form of colonialism that omits the geographical separation between the dominant and the subordinate population as they are "intermingled" with each other. Here, in this case, the highly educated Indians and their ideology intertwine with the British colonizers when it comes to thinking and looking at subordinate cultures and ends up generalizing them with the majority of the population.

Gabada women at a loom weaving their striped 'kerang'

The fourth chapter of the history textbook has included two pictures taken by Sunil Janah on the same page. Following the impact of the forest law introduced by the British that established government's right on forest and forest products, this page describes the problems that the tribal people faced while trading forest goods in the nineteenth century. In this section of the chapter, the writers are more interested in putting their fingers on the issue of the enormous amount of wealth that the tribal peoples had, became a reason for their plight. The greed of the outsiders (dikus) creates many problems for the tribals who have never thought of reaping the nature off for their profit. It starts with the problems that many tribal people experienced while the traders and money lenders came to them seeking either their labor or the forest products that they owned.

The first image shows women weaving cloths using forest products, and the second picture depicts that a tribal woman is working in a mat factory. Although the page begins with narrating the problems that the new form of the market economy created for many tribal peoples around the country, later it chooses to talk about a particular tribe, the Santals who lived in Hazaribagh and reared cocoons. It describes how the growing demand of Indian silk in European market acted as an impetus for a large number of business owners to look for the "silk growers." After recognizing the opportunity of making a considerable profit, the traders started sending their agents to the Santals for the silk, and they encouraged the Santal people to collect more cocoons by lending them money. Eventually, the Santals found that the traders were exploiting them by paying a minimal amount of money for the silk, which was at least five times less than what it was worth. They did not take much time to realize that traders were making a massive profit by cutting their wages or by not paying enough money for the cocoons. The chapter concludes by describing the problems related to trade by highlighting that many tribal people considered market and traders as their foe. A careful analysis will make it clear that the tension that brewed between tribal people and the traders is a result of thrusting capitalist economy upon the tribal people. Indubitably, a contrast between the ideology of a communal economy that the tribal peoples followed and the market centered ideology of a capitalist economy is visible. Thus, there is growing resentment amongst the tribal peoples for the traders borne out of their increasing demand for maximum profit through exploitation or by cutting privileges of other persons.

The first picture on the page shows that two tribal women are facing each other and weaving cloths happily. They are having a conversation and the woman who is facing us is smiling while doing her work. Both of them are wearing jewelry. It is clear from the picture that they are enjoying their work. The title of the picture in the textbook indicates that the women are Godara tribe. However, without mentioning Godara tribe elsewhere, the fourth chapter has selected their picture to help readers understand the problems created by the traders that many tribal peoples experienced in the past.

This picture is taken from the second part of the first section of the book "The tribals of India," written by Sunil Janah. In this segment of his book, Janah talks about the 'Gabadas,' a tribal group who live in Orissa. Janah laments that despite the uniqueness of their culture, very little has been written about them (Janah, 1993). In contrast, the textbook appears to be more inclined in including the neglected tribal peoples and share their story with the readers. Unfortunately, although it keeps the title used by the photographer for the image, there is a typological mistake that changes the name of the tribal group. It sheds light on the fact that the same ignorance has been shown by the editors of the history textbook who paid no attention to this error, especially because the book has reprinted ten times after its first publication in 2008.

Sunil Janah is known for expressing his political view using the lenses. He was the one who brought to light the grim picture of the famine in Bengal that was responsible for the death of three million people. Through his photography, he has always taken a bold political stance and brought forward the plight of the oppressed. During the second world war, the news department was under the British administration, and thus, they were able to suppress that news or facts that were potentially harmful to their image. However, even in such adversarial situation, Sunil Janah took a brave stance and published his photos that were able to successfully portray the oppression of the British ruler in front of the world (Vyawahare, July 11, 2012) (Pandya, July 9, 2012). Similarly, the picture named "Gabada women at a loom weaving their striped 'kerang.' Orissa", has a history that talks about the oppression of the forest department on Gabada people and the ruling power's effort to eradicate the unique culture of the Gabadas.

'Kerang' is one of the beautiful elements of Gabadas culture. It is a colorful cloth that they make for themselves. The usages of different vibrant color in the cloth is what makes it so unique and attractive. Unfortunately, Gabadas are not able to make 'kerang' anymore as the forest department does not allow them to collect the herbs which are used for dying the cloth. Consequently, 'Kerang' is going to extinct in the near future (Janah, 1993). Moreover, what makes it worse is that 'Kerang' is just one of the elements of tribal culture all over the country, which is facing a hard time and fighting for existence. So, in essence, it is a very political piece of art that showcases the ruthless authority of the forest department. The ideology of coloniality that is present in the power relationship as a form of authority between the forest officer and the Gabadas is also present as a form of knowledge in the textbook which impedes in picturing the tribals as full human beings. Because in their epistemology the definition of human is profoundly influenced by and similar to a "Western bourgeois genre of Man (Scott 2000; Weheliye 2014; McKittrick 2015 as cited in (Desai & Sanyab, 2016, pp. 712-713)).

In contrast, the chapter in the textbook does not provide any political background of the picture and thus makes the usage of the photo meaningless. The effort of making the textbook politically 'neutral' is visible here that circumvents every opportunity to describe the insidious effects of forest law and market economy on the tribal people. For instance, the picture is not attached to explain the repression of the forest laws that still exist and continue to affect tribal peoples in India. On the contrary, it is used in a part of the textbook that has portrayed the picture in an apolitical way and shows that tribal women are happily chatting and weaving cloth.

A HAJANG WOMAN IS WEAVING A MAT

There is another picture on the same page named "A Hajang woman is weaving a mat." This image shows a tribal middle-aged woman tied to her baby with a cloth behind her and weaving a mat. The face of the baby is visible on the left side of the lady. Sentences that are written under the title of the picture describe that tribal women were not only expected to do household works, but also had to carry their children to their workplace and take care of them while working in a field or factories. This description makes readers think that the lady is working in a factory that produces mats.

Conversely, according to the photographer, this picture portrays a glance of the communal and market free life of the Hajang, a tribal group of North Bengal. The women here are making a mat for their own use rather than to sell them in a market. The author here clearly says, "Hajangs, like all primitive, agrarian people, wove their own clothing, grew their own food crops...They had little need for money" (Janah, 1993, p. 98).

The inclusion of these two pictures in the page that talks about the exploitation of the tribal communities from the traders and money lenders, implies that the pictures are also about the same issue which in reality they are not. In addition to that, like the photo named "The most beautiful girl of the village," these two pictures do not contain anyone from the tribal community that the page is describing. To be more specific, while the page is talking about the Santals, it includes pictures of two other tribal communities named Gabadas and Hajangs whose lives are different from Santals. Importantly, while the last two pictures were taken in a politically unstable situation, the textbook has used them for a different purpose. The textbook has transformed the brave story of resistance of the tribal people into coping with new problems created by the traders and money lenders.

On a different note, while showing resistance towards invasion, the images of the Gabada women and the picture of a Hajang woman paint a picture of total calmness. That is very common for tribal people of India. A very similar observation has echoed in the words of Arundhati Roy who has shared her experience of spending a few months with the Khonds who were protesting against the big corporations and the government who wanted to capture their forest (Roy, 2012). Instead of showing the brave fight that the tribal peoples of India have historically put up against invasion, the chapter chose to state the problems they faced. It seems disinterested and thereby turns a blind eye to the other part of their history that shows how tribal people fought back together in a unique way to protect themselves from oppressors. In his own words, Sunil Janah describes;

"Despite the prevailing political tension, I found that they were relaxed and at ease. I was impressed by their calmness, their ability to face problems. I have never found such calmness during a workers' strike in Calcutta or Bombay. These people were not as insecure as industrial workers, totally depended on the wages of their factory jobs. Nature had provided the Hajangs with most of their basic needs, and they were not unduly disturbed by fears of the consequences of fighting with their landlords " (Janah, 1993, p. 101)

CONCLUSION

All the images that have been analyzed in this paper depict a political story and show an act of resistance that the tribal peoples took. This attitude towards authority and their fight to keep their culture alive without any outside interference reverberate as a common theme across all of the images. While the pictures represent an effort to keep a distance from the market economy by making products for themselves or collecting goods for their needs, the history textbook, driven by an ideology that is reinforced by both capitalism and colonialism, is more interested in painting a very different image. The images are attached to show tribal women as wage earners who are making products for the market (i.e., for the factory or the traders). However, the critical examination of the inclusion of these three photographs, reveal three typologies of the hidden ideology that makes the writers attached a different meaning to the images. Firstly, there is a vivid effort to bring different tribal communities under one umbrella term that is "tribal." It serves as evidence of a significant influence of internal colonialism on the ideology that worked behind creating the textbook. Secondly, images have been depoliticized, and thus, they ended up telling a completely different story that shows the intention of the storytellers. The readers are not supposed to know the political struggle and the acts of resistance towards assimilation that prevent the tribal peoples of India from going extinct. Last, but not least, a closer look at the pictures and their context in the textbook unveil the fact that inclusion of their story is nothing more than tokenism. There is no effort to bring their real stories to the general public and the reader.

REFERENCES

Desai, K., & Sanyab, B. N. (2016). Towards decolonial praxis: reconfiguring the human and the Curriculum. [ Links ]

Janah, S. (1993). The tribals of India. (J. Ghosh, Ed.) CalCutta: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

NCERT. (2017). Our Pasts -III, Part -1. New Delhi: National Council of Educational Research and Training. [ Links ]

Nurullah, S., & Naik, J. P. (1948). History of Education in India: During the British Period. Bombay. [ Links ]

OUR PASTS - III , Part I. (2017). New Delhi, India: National Council of Educational Research and Training. [ Links ]

Pandya, H. (July 9, 2012). Sunil Janah, Who Chronicled India in Photographs, Dies at 94. The New Yor Times, Asia Pacific. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/10/world/asia/sunil-janah-who-photographed-bengal-famine-dies-at-94.html [ Links ]

Roy, A. (2012). Walking with the Comrades. USA: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Tejeda, C., & Espinoza, M. (n.d.). Towards a Decolonizing Pedagogy: Social Justice Reconsidered. [ Links ]

UNICEF. (2011). Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/adolescence/files/SOWC_2011_Main_Report_EN_02092011.pdf [ Links ]

Vyawahare, M. (July 11, 2012). The Photography of Sunil Janah. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/11/the-photography-of-sunil-janah/ [ Links ]

Sudhashree Girmohanta: Graduate Center, City University of New York Estados Unidos da América do Norte Master of Liberal Arts, Urban Education.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5005-8142

E-mail: sudhashreegirmohanta5@gmail.com