Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología

versão impressa ISSN 1946-2026

Rev. Puertorriq. Psicol. vol.22 San Juan 2011

Artículo

Exploratory study of the role of family in the treatment of eating disorders among Puerto Ricans1

Elizabeth Guadalupe-Rodríguezi,I; Mae Lynn Reyes-Rodríguez2,II; Cynthia M. BulikII

I University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus

II University of !orth Carolina at Chapel Hill

Abstract

In Latino culture, the family is a major source of social support. We explored the needs and the role of the Puerto Rican eating disorders patient's family in the treatment process by conducting a focus group with five close relatives of youth with eating disorders. Qualitative analyses indicated the need to integrate the family into treatment and to provide management guidelines to assist with the resolution of situations that emerge frequently during recovery. These results underscored the importance of developing and incorporating psychosocial interventions that include family support and guidance for relatives of Puerto Rican youth patients with eating disorders.

Keywords: Eating disorders, caregiving, family, focus group, Puerto Ricans

Resumen

Para la cultura latina, la familia constituye una de las mayores fuentes de apoyo social. Este estudio exploró, por medio de un grupo focal, las necesidades y el rol de la familia puertorriqueña en el tratamiento de pacientes jóvenes con trastornos de la conducta alimentaria. El estudio se realizó con cinco familiares de pacientes jóvenes con trastornos de la conducta alimentaria. El análisis cualitativo reveló la necesidad de integrar a la familia en el tratamiento y la necesidad de proveerles unas guías de manejo que les permitan asistir al paciente y a la familia en las diferentes situaciones que surgen como parte del proceso de recuperación. Estos resultados resaltan la importancia de desarrollar e incorporar intervenciones psico-sociales que incluyan apoyo y dirección para los familiares de pacientes puertorriqueños/as con trastornos de la conducta alimentaria.

Palabras claves: Trastornos alimentarios, familia, grupo focal, puertorriqueños/as

In eating disorders (ED), the study of caregiver distress is an evolving area and the factors that contribute to distress in this population remain underspecified. The social context with the most immediate effects on the individual, and that is most immediately influenced by the individual is the family (Wood & Miller, 2005). Family is defined as a constellation of at least two intimates, living in close proximity, having emotional bonds – they may be positive or negative – a history, and an anticipated future (Wood & Miller, 2005). Based on that core definition, family values, functioning, and relationships have important influence over a person's health, illness, and disease management and the illness has profound effects on family functioning and caregiver well-being (Pernice-Duca, 2010). ED and especially anorexia nervosa (AN) entail many challenges to caregivers, including lack of information about the illness, stressful experiences in obtaining adequate help through health services, ill-informed practitioners blaming parents for the illness, the psychological needs of carers themselves, and poor social support and understanding for carers (Kyriacou, Treasure, & Schmidt, 2008).

There has been little research on the impact of caring for individuals with ED. Caring for a person with ED has been associated with psychological distress and poor life quality of carers (Kyriacou, Treasure, & Schmidt, 2008; de la Rie, van Furth, De Koning et al., 2005). Addressing carers' needs may impact on prognostic outcome. A preliminary study found that carers of individuals with AN experience more difficulties and distress than carers of people with psychoses (Perkins, Winn, Murray, Murphy, & Schmidt, 2004). Another study found greater impairment in mental health, vitality and emotional role functioning in carers of individuals with ED relative to a normal reference group (de la Rie, van Furth, De Koning et al., 2005). Interventions that involve the family are recommended for adolescent patients; however, there is less certainty about best practices for adult patients (Perkins, et al., 2004). Previous research has found that the parents of adult patients report high levels of distress (Haigh & Treasure, 2003) and find the caring role burdensome (Whitney, Murray, Gavan, Todd, Whitaker, & Treasure, 2005). Other research has found that involving the family in the treatment of adolescents with AN has proven to be helpful (le Grange, Lock, & Dymek, 2003). Also, preliminary evidence seems to support the use of family-based treatment for adolescent with bulimia nervosa (BN) (le Grange, Crosby, Ralthouz, & Leventhal, 2007; Loeb & le Grange, 2009).

Carers of people with ED report that most of their social support comes from family and friends, however, this support is limited, typically due to the stigma and lack of understanding surrounding ED (Kyriacou, Treasure, & Schmidt, 2008). Consequently, many carers feel isolated and ill-prepared to deal with the illness. Previous studies found that patients who had received family therapy continued to do significantly better than those who had received individual therapy, in part because the involvement of the family ensured a psychoeducational intervention for relatives of patients with ED which can be an important step in recovery (Lock & le Grange, 2005). The role of the family in the treatment of ED in Caucasian individuals has transformed radically throughout history. In the past decade, a complete reversal has occurred in which intervention approaches actively engage family members in treatment. For adolescents, two traditions have evolved: Maudsley (Russell, Szmukler, Dare, & Eisler, 1987) and parent training methods (Hagenah & Vloet, 2005; Zucker, Marcus, & Bulik, 2006). The Maudsley model was developed for treating adolescents with AN focusing on the weight restoration guided by parental support and control. The active role of the family in restoring healthy eating patterns in the adolescent with AN enhances recovery (Eisler, 2003; Eisler, Dare, Hodes, Russell, Dodge, & le Grange, 2000; Wilson, Grilo, & Vitousek, 2007). The application of Maudsley-like family therapy approaches in adults with ED was less promising (Eisler, Dare, Russell, Szmukler, le Grange, & Dodge, 1997; Russell et al., 1987). Some studies used the Maudsley model for adolescents with BN (Dodge, Hodes, Eisler, & Dare, 1995; le Grange & Lock, 2005; le Grange, Lock, & Dymek, 2003). Maudsley-like family involvement in adolescent BN patients appears to be important in regularizing eating patterns, decreasing binge eating and purging episodes, and providing emotional support (le Grange, & Lock, 2005). The parent training intervention (PTI) is designed to help parents to develop the necessary skills to manage their child behaviors. Using a group format between 8 to 22 weeks sessions, the PTI focuses on three specific areas: parental role modeling, establishing good eating and exercising habits and encouragement and praise for good eating and exercising (Zucker, Marcus, & Bulik, 2006).

Altabe and O'Garo (2002) discussed the importance of the role of the family and its relationship to food and body image in Latino culture. Young Latina women tend to live with their families longer than do their European American counterparts. Also, Latino families tend to promote more traditional values (e.g., familism, respect, religion) (Altabe & O'Garo, 2002). Culture, context, and language are essential considerations for the culturally competent care of Latinos (Bernal & Flores-Ortiz, 1982; Marín & Marín, 1991). Studies with Puerto Rican adolescents with depression have underscored the importance of the family as a cultural value affecting recognition of the condition (Rosselló & Bernal, 1999; Rosselló & Bernal, 2005). These studies have also evidenced that family factors like communication, emotional involvement, accomplishment of tasks within the family, and marital conflicts have a predictive value in adolescent depression (Rosselló & Bernal, 1999; Rosselló & Bernal, 2005). Furthermore, the perception of emotional involvement and acceptance from family members appears to be extremely important for Latinos (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2005). Our experience working with adults with BN in Puerto Rico highlights the need to incorporate the family early in the treatment process as a necessary cultural adaptation for Latinos (Reyes, Rosselló, & Matos, 2006). The purpose of the present study was to explore the needs and the role of the Puerto Rican ED patient's family in the treatment process.

Method

Participants

The study was carried out using a sample of five participants from three families (three men and two women) between the ages of 47 and 57. All participants had or had had a child between the ages of 15 and 22 with an ED; two children with AN history and one child with BN. The minimum schooling was a bachelor's degree and the maximum was graduate studies. All the participants were volunteers and of Puerto Rican nationality. Informed consent was obtained for all of the participants.

Instrument

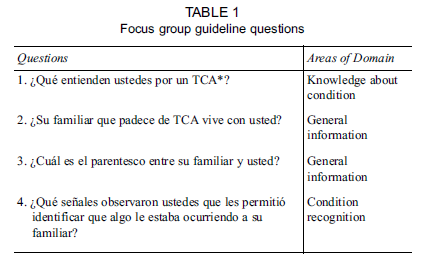

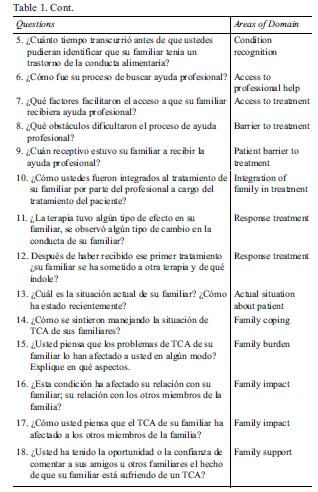

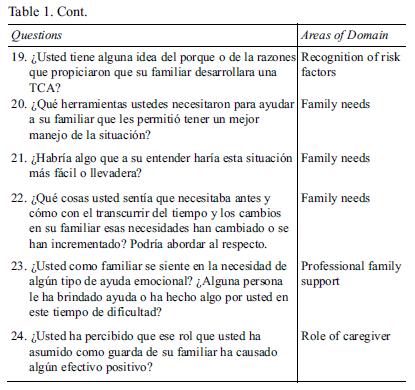

We employed a focus group design. First, participants completed a demographic questionnaire assessing sex, schooling, occupation, and other questions related to the offspring's ED. We developed guideline questions for the focus group concentrating on knowledge about ED, recognition of the condition, the impact of the ED on the family, obstacles to treatment, and the needs of the parents who have a child with an ED. In Table 1 the Spanish guideline questions with the main domains are presented.

Procedure

The research proposal was approved by the Institutional Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. The inclusion criteria were only availability to participate in the focus group voluntarily and having a relative with a current or past ED. Participants were identified through the records of the Bulimia Project. The Bulimia Project was an NIMHfunded post doctoral fellowship ("Bulimia Nervosa: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Latinos") designed to adapt cognitive behavioral treatment for BN with Latinos/as in Puerto Rico. Each individual authorized communications after treatment in the outpatient eating disorders clinic at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. An invitation was sent to nine parents or legal custodian of patients who had consented to be contacted after treatment. A letter of invitation indicated that participation was voluntary and any services they were receiving at the clinic would not be affected by their decision.

Individuals contacted research personnel, were informed about the course of the study, informed that the focus group would be videotaped, and provided with details on the timing of the group. A question guideline was used in order to maximize our ability to assess the needs of relatives of individuals with EDs. Before initiating the group, instructions were given on how the group would be conducted and informed consent was obtained. The focus group was conducted by two facilitators with experience in focus groups; in addition, one assistant took detailed notes of the discussion and interactions. The discussion lasted two hours. The session was transcribed textually and a number was assigned to each participant to identify his/her contribution throughout the discussion. In order to guarantee the privacy and confidentiality of the participants, their names were not used in the analytic process. The videos are under lock in the University Center for Psychological Services and Research, University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras and are accessible only to authors.

Coding process and analysis

Content and thematic analysis of qualitative data was conducted using the framework analysis (Falemeh, 2004) and NVivo software (NVivo, March 2008). As a first step, two independent coders identified categories from the transcript of the focus group discussion. Second, consensus coding was developed by the two coders based on the categories with the highest frequencies. The frequency on each category was determined by the number of times the specific theme was raised throughout the discussion. Third, quotes were chosen from the group that best represented the categories. Fourth, a chart was created to organize the quotes according to the appropriate thematic content.

Results

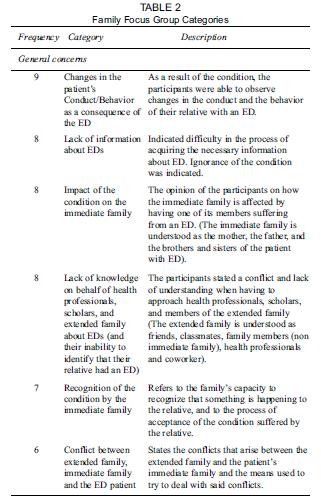

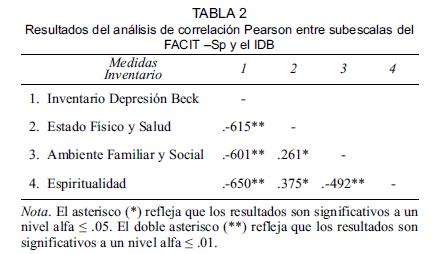

The categories were classified in two heading; general concerns and family members needs. Table 2 presents the ten categories that compound both heading.

General concern categories

1. Lack of information about the condition

Participants consistently indicated the lack of available information about EDs. They highlighted that eating disorders are not common knowledge and this negatively impacts their ability to understand the disorders and learn about them.

Father # 1:

"But I never saw it, not even in the university did they talk about this topic, and when I saw it for the first time, well, I didn't understand it."

2. Recognition of the condition by the immediate family (IF)

The participants recounted the difficult process of acceptance of the condition by some family members was and the fact that the ED itself was difficult to identify.

Father # 3:

"In our case it was easy and at the same time difficult, easy because it was evident right from the start because our daughter's deterioration was so sudden, it's been less than three months, it was very quick and dramatic."

Mother # 1:

"Then she leaves on a trip and I start searching the whole house and I find boxes of laxatives and that's when I went crazy because it's where I had to face the reality of what I had been looking for months. That's when I said, 'forget it this is real'."

3. Impact of the condition on the Immediate Family (IF)

Many carers felt that the illness had profoundly affected them. Parents were concerned about the effects on the family's social life and difficulties in making future plans. They also pointed out difficulty in the process of family coping and adaptation to the illness.

Mother # 2:

"We don't go out like we used to, so that she won't have to stay by herself because we're worried, we're afraid. She doesn't go out anymore; we used to go out to eat often, but not now."

Mother # 2:

"And at the beginning it was very hard, very difficult because the oldest sister didn't know what to say, what to say to her, 'You have to eat', 'Haven't you eaten?', 'What did you eat?', 'What are you eating?', 'What don't you eat?' And here I was, well, behind her making all sorts of signs and no, don't say or say and then her father's preoccupation calling 10 to 12 times daily, What?, How's my girl?"

4. Conflict between extended family and relatives with an ED patient

Carers felt that although friends and extended relatives tried to provide support, they could not appreciate the difficulties experienced by both parents and child in dealing with the ED. They also expressed frustration caused by others' lack of understanding. As a result of this, participants expressed conflict between the extended family and themselves.

Father # 2:

"And I'll be really sincere, I believe you have to get everyone involved, not only the parents, but also the grandparents and the siblings right from the start so they'll understand because my father is one who is still driving me crazy,… and then we even had to ask the psychologist to have a session with them and to explain because they wouldn't believe us, because you know, that's how you say that in their time that didn't exist. And then we had to have a meeting so that my father would hear from her own mouth how things are because he was driving us crazy, driving us mad, that we weren't doing the right thing, and then listening to everyone's opinions and giving his opinion too."

5. Changes in the Conduct/Behavior as a consequence of the ED

Participants indicated that since the family began dealing with the ED, they observed changes in the patient's behavior, such as: changes in her personality from introverted to extroverted, increase in the consumption of food or on the contrary stopping eating, using laxatives, difficulty expressing the affection and resisting being on the receiving end of emotion of affection.

Father # 3:

"Um… to give an example, […] our daughter would never, even in the immediate family environment, get up in the morning and leave her room if she wasn't completely dressed […] well, for some time now she is coming out without putting on her pants or shirt […] I don't think so, that it's negative, first because that's not her, she was very modest, that unlike the other one who was a little more liberal in her expression."

6. Lack of knowledge on behalf of the health professionals, scholars, and the extended family regarding the EDs (and their inability to identify that the student or relative has an ED).

The participants noted that the lack of knowledge among the health professionals, scholars, and the extended family was particularly problematic in the process of dealing with the ED.

Mother # 1:

"I went to the gastroenterologist the other day, and I don't know if I should return, you remember I had told you about that. Because the first thing he tells her is that she has to take laxatives. Then I open my eyes wide and I tell him, 'Look doctor, what happens is', right there I said to myself, 'I have to stop this right here. It's just that we have had a situation with the laxatives and I don't want to go into details right now'. The doctor said, 'But that's the only thing she can do.' Then I became very nervous and anxious. Then I realized that she didn't want to tell the doctor anything about her eating disorder because she became angry. She said, 'Why is he so ignorant you just about told him.' Well, in other words, I think that from professionals all the way to school should undergo a process of education."

7. Concrete actions in dealing with ED patient: A change in the material environment of the home and its effect (more vigilance or supervision of the patient)

The patient's family indicated that as a result of complicated situations, they found themselves having to make certain decisions about the family situation. Among the decisions made were increased surveillance and eliminating obstacles to monitoring as in the case shown below.

Father # 1:

"Some situations come up in the family, like one says. Well, I stayed home for almost a whole year at the beginning. I did things I had to do; I don't know if what I decided, I took away all the doors of the bedrooms, there were no bedroom doors, no bathroom doors. When she said, 'Pop', I said, 'There are no doors.' I had to take away the doors and there were no doors in any of the rooms. But I always did it trying to find a way for her to understand."

Mother # 1:

"And then I placed myself more at the forefront."

Family needs categories

8. The needs of relatives of a patient with an ED The participants pointed out the needs for tools by which they can influence the health of their ill family members.

Father # 3:

"But there's something that I observe as a whole, at least along the way, some of what they have brought and we too of our own experience and of what we now know due to what we have all shared together and you said it, tools, we need them."

9. The need for psychological support for the family of ED patients

The participants expressed the need for emotional support to help them feel more capable of dealing with the situation.

Mother # 1:

"Like I say to the psychologist, so many people have recommended this doctor to me, this psychiatrist, I go there because at given moments, I feel I have to go because we parents basically break down with our children and we struggle day to day, but it's very hard."

10. The need for immediate management guidelines Relatives of the patients indicated that on many occasions in daily life they simply do not know what to do. They expressed the need for some guidelines to help them deal appropriately and more confidently with difficult situations that arise regularly with their family member with an ED.

Father # 3:

"At least, my suggestion, I believe that one or various protocols have to be developed depending on the day to day immediate management situations because when the girls are here or if their appointment is in the afternoon, well it's easier, but when she doesn't have an appointment, well then they are alone, and we're alone. But we continue having the need for some kind of minimum basic management protocols. Should we tell them the truth? What should we encourage? What shouldn't we encourage?"

Discussion

Comments offered by these parents in the focus group highlight the both the need and the desire of parents to be involved with the treatment of EDs. Involving the family in the treatment is relevant considering the complexity of the illness and the Latino cultural background. Furthermore, integrating the family in the earliest stages of detection and intervention may assist with motivation for treatment and help the family deal with the complex processes of supporting their loved one who is suffering from a perplexing illness, while simultaneously providing practical guidance for such behaviors as managing medical complications. With few exceptions, parents and relatives have been noticeably absent in the research literature on treatment (Braswell, 1991; Kovacs & Sherrill, 2001).

In general, existing evidence-based interventions with Latinos have not included the participation of parents or relatives in the treatment of their children or older patients with EDs. As noted by Kovacs and Sherrill (2001) the involvement of parents or relatives in treatment has a favorable effect on retention and adherence to treatment. Parents or relatives may play an essential role in managing the symptoms of their children or relatives and can act as resources to minimize the impact of the emotional condition on the family dynamics. Parents or relatives may misinterpret symptoms and emotional behavior, which could lead the patient to feel experience lack of support, loneliness, and frustration. Improved understanding of the illness could lead to better acceptance and greater facility of managing day to day symptoms and behaviors.

The participants pointed out the absence of appropriate information about EDs even in health professionals, scholars, and extended relatives. This absence or mis-information was problematic and affected the impact that extended family had on the recovery process. Although no comprehensive guide could ever be developed to deal with every aspect of these complicated illnesses, parents asked for some guidelines or management strategies to guide them with dealing with some of the basics of care of individuals with EDs. Training parents in skills to manage the illness may improve outcome by reducing interpersonal maintaining factors.

The participants in this group unanimously underscored the importance of bringing family into treatment, and providing appropriate education for extended family. The family is a strong Latino cultural value (familismo). Latino families tend to reflect a profound interdependence between parents and their children, which often continues into adulthood (La Roche, 2002). In Puerto Rico, family is often involved with their offspring even beyond the age of 21 years. In our experience with the ED outpatient clinic, 41% are young adults and we have to incorporate their family as part of the treatment.

The fact that participants emphasized the need for psychological support for themselves is consistent with previous studies indicating that family caregivers of individuals with mental disorders often experience mental health difficulties of their own (Perkins, Winn, Murray, Murphy, & Schmidt, 2004). It is clear from several studies that carers of people with ED have high levels of distress, associated in some cases with depression and anxiety and that their needs often go unmet, resulting in an impaired quality of life (Kyriacou, Treasure, & Schmidt, 2008).

Conclusion

This represents the first formative study to be conducted in Puerto Rico regarding the needs of family's members of youth with EDs. One limitation of this study is the small sample; only 5 participants from 3 families participated in the study. Although larger qualitative and quantitative studies are required to further specify and refine our understanding of the needs of these individuals, these exploratory findings suggest that families of individuals with ED who are of Puerto Rican cultural background request greater support and information, enhanced education for health care professionals about EDs, involvement of the family in treatment, and guidelines to assist them with dealing with common situations facing family caregivers. Following these larger, more definitive studies, efforts should be made to translate the needs of parents and family members into finding culturally appropriate ways to incorporate family into treatment, developing psycho-educational and supportive interventions for relatives of patients with ED, and evaluating the impact of such interventions on ED treatment outcome. A family treatment approach with this population is considering the ED as a life family problem that affected the relationship between the family members (Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure, & Dodge, 2001).

REFERENCES

Altabe, M. & O' Garo, K. (2002). Hispanic Body Images. In T. Cash & T. Pruzinsky (Eds.), Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. (pp. 251-477). New York, N.Y.: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Bernal, G. & Sáez-Santiago, E. (2005). Toward culturally centered and evidenced based treatments for depressed adolescents. In W. M. Pinsof &. A. J. Lebow (Eds.), Family Psychology: The Art of the Science. (pp. 471-489). Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bernal, G. & Flores-Ortiz, Y. (1982). Latino familias in therapy: Engagement and evaluation. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 8, 357-365. [ Links ]

Braswell, L. (1991). Involving parents in cognitive-behavioral therapy with children and adolescents. In P. C. Kendall (Ed.), Child and adolescents' therapy. (pp. 316-351). New York: Guildford Press. [ Links ]

Dare, C., Eisler, I., Russell, G., Treasure, J., & Dodge, E. (2001). Psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa: Randomized controlled trial of out patient treatments. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178, 216-221. [ Links ]

de la Rie, S. M., van Furth, E. F., De Koning, A., Noordenbos, G., & Donker, M. C. (2005). The quality of life of family caregivers of eating disorder patients. Eating Disorders, 13, 345-351Links ] Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif">.

Dodge, E., Hodes, M., Eisler, I., & Dare, C. (1995). Family Therapy for bulimia nervosa in adolescents: An exploratory study. Journal of Family Therapy, 17, 59-77. [ Links ]

Eisler, I. (2003). The empirical and theoretical base of family therapy and multiple family day therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Journal of Family Therapy, 27, 104-131. [ Links ]

Eisler, I., Dare, C., Russell, G. F., Szmukler, G., le Grange, D., & Dodge, E. (1997). Family and individual therapy in anorexia nervosa: A 5-year follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 1025-1030. [ Links ]

Eisler, I., Dare, C., Hodes, M., Russell, G., Dodge, E., & le Grange, D. (2000). Family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: The results of a controlled comparison of two family interventions. Journal of Child Psychol Psychiatry, 41, 727-736. [ Links ]

Falemeh, R. (2004). Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 63, 655-660. [ Links ]

Hagenah, T. & Vloet, U. (2005). Parent psychoeducation groups in the treatment of adolescents with eating disorders. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie, 54, 303-317. [ Links ]

Haigh, R. & Treasure, J. (2003). Investigating the needs of carers in the area of eating disorders: Development of the Carers'Needs Assessment Measure (CaNAM). European Eating Disorders Review, 11, 125-141. [ Links ]

Kovacs, M. & Sherrill, J.T. (2001). The psychotherapy management of major depressive and dysthymic disorders in childhood and adolescence: Issues and prospects. In I. M. Goodyear (Ed.), The depressed child and adolescent. (pp. 325-352). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kyriacou, O., Treasure, J., & Schmidt, U. (2008). Understanding how parents cope with living with someone with anorexia nervosa: Modeling the factors that are associated with carer distress. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41, 233-242. [ Links ]

La Roche, M. J. (2002). Psychotherapeutic considerations in treating Latinos. Harvard Review Psychiatry, 10, 115-122. [ Links ]

le Grange, D., Crosby, R. D., Ralthouz, P. J., & Leventhal, B. L. (2007). A randomized controlled comparison of family-based treatment and supportive psychotherapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 1049-1056. [ Links ]

le Grange, D. & Lock, J. (2005). Family-Based treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa: The Maudsley approach. !ational Eating Disorders Information Center. Retrieved from www.nedic.ca.

le Grange, D., Lock, J., & Dymek, M. (2003). Family-based therapy for adolescents with bulimia nerviosa. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 57, 237-251. [ Links ]

Lock, J. & le Grange, D. (2005). Family-based treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37, S64- S67. [ Links ]

Loeb, K. L. & le Grange, D. (2009). Family-Based Treatment for Adolescent Eating Disorders: Current Status, new applications and future directions. International Journal of Child Adolescent Health, 2, 243-254. [ Links ]

Marín, G. & Marín, B. V. (1991). Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Nvivo (March, 2008). QSR International. [ Links ]

Perkins, S., Winn, S., Murray, J., Murphy, R., & Schmidt, U. (2004). A qualitative study of the experience of caring for a person with bulimia nervosa. Part 1: The emotional impact of caring. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 36, 256-268. [ Links ]

Pernice-Duca, F. (2010). Family network support and mental health recovery. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36, 13-27. [ Links ]

Reyes, M. L., Rosselló, J., & Matos, A. (2006). Cognitive behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa in Latinos: Cultural adaptation and pilot study. International Conference on Eating Disorders of the Academy for Eating Disorders. June 7-10. Barcelona, Spain. [ Links ]

Rosselló, J. & Bernal, G. (1999). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal treatments for depression in Puerto Rican adolescents. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 67, 734-745. [ Links ]

Rosselló, J. & Bernal, G. (2005). New developments in the cognitivebehavioral and interpersonal treatments for depressed Puerto Rican adolescents. In E. Hibbs & P. Jensen (Eds.), Psychosocial treatments for children and adolescent disorders: Empirically based approaches. (pp. 187-218). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press. [ Links ]

Russell, G. F., Szmuckler, G., Dare, C., & Eisler, I. (1987). An evaluation of family therapy in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 1047-1056. [ Links ]

Whitney, J., Murray, J., Gavan, K., Todd, G., Whitaker, W., & Treasure, J. (2005). Experience of caring for someone with anorexia nervosa: Qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 444-449. [ Links ]

Wilson, G. T., Grilo, C. M., & Vitousek, K. M. (2007). Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist, 62, 199- 216. [ Links ]

Wood, B. L. & Miller, B. D. (2005). Families, health and illness: The search for mechanisms within a systems paradigm. In W. M. Pinsof & J. L. Lebow (Eds.), Family psychology: The art of the science. (pp. 493-520). Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Zucker, N., Marcus, M., & Bulik, C. M. (2006). A group parenttraining program: a novel approach for eating disorder management. Eating and Weight Disorders, 11, 78-82. [ Links ]

1 Nota: This article was submitted for evaluation on January 2010 and accepted for publication on December 2010.

2 Send all correspondence to: Dr. Reyes-Rodríguez, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 101 Manning Drive, CB #7160, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7160, Voice: (919) 966-7358, Fax: (919) 966-5628, e-mail: maelynn_reyes@med.unc.edu.

i Author's Note: This work was done during the Hispanic COR: Training in Biopsychosocial Research (T34 -MH19134) fellowship of the first author from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. Other support was provided from NIMH through grants (F32 MH66523- 01A1) at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus and (3R01MH082732) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We are grateful to Mr. Carlos Morales for assistance with the observation and detailed notes of the focus group discussion.