Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología

versão impressa ISSN 1946-2026

Rev. Puertorriq. Psicol. vol.23 San Juan 2012

Artículos

Gender differences in Hispanic children evaluated with the TEMAS and BASC tests1

Elsa B. CardaldaI2; Giuseppe CostantinoII; José V. MartínezIII; Nyrma Ortiz-VargasIV; Mariela León-VelázquezIV

IInteramerican University of Puerto Rico Ponce School of Medicine and Health Sciences

IITouro College Lutheran Medical Center/Lutheran Family Health Centers

IIICarlos Albizu University

IVPrivate practice

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine gender differences in adaptive vs. maladaptive social problem skills as assessed by the TEMAS (Tell-Me-A-Story) personality/narrative test. Samples included Hispanic girls and boys between the ages of 9-11, attending public schools in Puerto Rico or in New York. Results on the TEMAS were compared to another personality test, the Behavior Assessment System for Children - Self Report of Personality (BASC-SRP). Comparisons used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in order to determine significant gender differences between the sites of PR and NY. For students sampled in Puerto Rico results showed significant Reality Testing and Verbal Fluency. However, no significant gender differences were found in the New York sample. With the BASC gender differences were found in the clinical scale of Anxiety in the Puerto Rican sample, while no significant differences were found in the New York sample. Girls in PR showed a relative strength in several skills, whereas no such gender differences were noted in NY.

Keywords: TEMAS test, BASC, Hispanic children, gender differences, multicultural assessment.

Resumen

El propósito de este estudio era examinar las diferencias de género en términos de las destrezas sociales de resolver problemas de forma adaptativa o maladaptativa. Las destrezas fueron evaluadas con la prueba proyectiva/narrativa TEMAS (Tell-Me-A-Story) a niños y niñas hispanos entre las edades de 9-11 que asistían a escuelas públicas en Puerto Rico y Nueva York. Los resultados del TEMAS fueron comparados con otra prueba de personalidad, el Behavior Assessment System for Children - Self Report of Personality (BASC-SRP). Las comparaciones utilizaron la prueba ANOVA para determinar si existían diferencias significativas entre los niños y las niñas que vivían en PR o en NY. Los estudiantes muestreados en Puerto Rico mostraron diferencias significativas de género en las escalas del TEMAS en Motivación de logro, Cotejo de la realidad y Fluidez verbal. Sin embargo, no se encontraron diferencias significativas por género en la muestra de Nueva York. Diferencias significativas por género fueron encontradas en la escala clínica de ansiedad del BASC en la muestra de Puerto Rico, pero no en la muestra de Nueva York. Las niñas en PR muestran una fortaleza relativa en los aspectos medidos de destrezas de resolución de problemas, pero ese no es el caso en Nueva York.

Palabras clave: Prueba TEMAS, BASC, niños hispanos, diferencias de género, evaluación multicultural

Gender Differences in Hispanic Children Evaluated with the TEMAS and BASC Tests

The large disparities in mental health care that Hispanic youth face dictate the need for evidence-based, culturally competent assessment techniques. Despite this need there are few personality tests validated for the Hispanic population. One personality test is the TEMAS (Tell-Me-A-Story), a multicultural instrument available for Hispanic children (Costantino, 1987; Costantino, Dana, & Malgady, 2007; Costantino, Malgady, & Rogler, 1988). Another personality test available for Hispanic children is the BASC (Behavior Assessment System for Children); (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1998). The TEMAS measures adaptive and maladaptive social problem solving skills in different settings, and the BASC measures personal adjustment and clinical and school maladjustment in different scenarios. Both are personality tests, one is a narrative/projective measure that can be administered in a individual or group format, and the other, an inventory that can be reported by self or others (parents or teachers). These tests can function as complementary measures since both address adjustment and maladjustment issues in children (Flanagan, 1995). Both instruments allow an assessment of personality strengths and weaknesses which are useful in the evaluation of resiliency in atrisk students.

The TEMAS test has been standardized with Hispanic children in New York City, with Hispanic children in Puerto Rico, and with Argentinean children in Buenos Aires (Costantino, Malgady, Casullo, & Castillo, 1991). As a multicultural instrument, the TEMAS has the support of extensive empirical studies in the US comparing the minority and non-minority versions of the test with samples of children from Hispanic, White and Black backgrounds (Costantino & Malgady, 1983; Costantino, Malgady, Colón-Malgady, & Bailey, 1992; Costantino, Malgady, Rogler, & Tsui, 1988; Costantino, Malgady, & Vázquez, 1981; Krinsky, Costantino, & Malgady, 1999; Malgady, Costantino, & Rogler, 1984). Cross cultural studies have been performed with Puerto Rican, Argentinean, Mexican-American, Salvadorian, Peruvian, Chinese, and Italian children (Bernal, 1991; Cardala, Costantino, Ortiz-Vargas, León-Velázquez, & Jiménez- Suárez, 2007; Cornabuci, 2000; Costantino, & Malgady, 2000; Costantino, Malgady, Casullo, & Castillo, 1991; Costantino, Malgady & Faiola, 1997; Dupertuis, Silva Arancibia, Pais, Fernández, & Rodino, 2001; Fantini, Aschieri, Bevilacqua, & Augello, 2007; Millán- Arzuaga, 1990; Sardi, Summo, Cornabuci, & Sulfaro, 2001; Sulfaro, 2000; Summo, 2000; Walton, Nuttall, & Vazquez-Nuttall, 1997; Yang, Kuo, & Costantino, 2003). Furthermore, other studies have established the validity (Costantino, Malgady, Colón-Malgady, & Bailey, 1992; Costantino, Malgady, & Rogler, 1988; Costantino, Malgady, Rogler, & Tsui, 1988) and clinical utility (Cardalda, Costantino, Sayers, Machado, & Guzmán, 2002; Cardalda, Figueroa, Hernández, Rodríguez, Martínez, Costantino, Suárez, & León, 2008; Costantino, Rand, Malgady, Maron, Borges-Costantino, & Rodríguez, 1994; Malgady, Costantino, & Rogler, 1984) of the TEMAS test.

Gender differences have been reported before in studies using the TEMAS, with girls showing higher verbal fluency in the production of stories than boys (Costantino & Malgady, 1983; Costantino, Malgady, & Vázquez, 1981). This finding is significant in light of the fact that verbal productivity as measured by the TEMAS has been correlated with school functioning in Hispanic students living in Puerto Rico and in New York (Cardalda, 1995; Cardalda, Costantino, Ortiz-Vargas, León-Velázquez, & Jiménez-Suárez, 2007). In the referred studies with Hispanic samples from Puerto Rico and New York, Achievement motivation as measured by the TEMAS was significantly correlated to school functioning criteria. Moreover, samples of children in Puerto Rico have showed that scales from the BASC instrument correlated significantly with school grades (Cardalda, Costantino, Martínez, León-Velázquez, Jiménez-Suárez, & Ortiz-Vargas, 2011).

Another gender difference reported is that girls tend to obtain higher school grades than boys (Cardalda, Costantino, Jiménez- Suárez, Leon-Velázquez, Martinez, & Ortiz-Vargas, 2011). This is consistent with a pattern reported by the Department of Education in Puerto Rico, with girls showing better academic progress than boys (Sanjurjo Meléndez, 2006). Recent educational trends in Puerto Rico and in the US show Hispanic women in higher education earning substantially more bachelor's degrees than Hispanic men (Cámara Fuertes, n.d.; Rios Orlandi, 2005; The Condition of Education, 1995). Latina girls attending school in the US obtain better grades and drop out less than boys (Ginorio & Huston, 2001). Then, it is plausible that certain skills measured by the TEMAS and the BASC can help us understand what protective factors may help girls succeed in school.

The Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) is a multimethod, multidimensional approach for evaluating the behavior and self-perceptions of children aged 2 to 18, across both maladaptive and adaptive behavior (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1998). The BASC has five main components- including the Structured Developmental History, Parent Rating Scale, Teacher Rating Scale, Self Report of Personality, and Student Observation System. The standardization study of the BASC included Hispanics in the US and demonstrated adequate internal consistency, test–retest reliability and validity (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1998). The BASC has Spanish and English versions, using multiple informers in different scenarios. With the BASC self report version, children describe their emotions and selfperceptions.The BASC self report test is an omnibus personality inventory, consisting of statements that are responded to as True or False.

The BASC is a test used as a guide for clinicians to evaluate the difficulties and day-by day problems confronted by children and adolescents. The BASC represents one of the most widely used behavioral self-report measures of mental disorders symptomatology in the field (Flanagan, 1995; Sandoval & Echandia, 1994). A review by Gladman and Lancaster (2003). reported that the BASC test is a comprehensive and psychometrically sound assessment tool with much to offer psychologists that work with children and adolescents. This test lends support in making differential diagnoses according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R) and problem areas covered by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (Flanagan, 1995; Merenda, 1996).

There is a lack of studies using the BASC- Self- Report because most of the research conducted has used the Teacher Report Form or Parent Report Form. Also, there is a limited range of studies using the BASC for Hispanic samples with the Spanish version (e.g., Dulin, 2001; Frontera-Benvenutti, 1992; McCloskey, Hess, & D'Amato, 2003; Serrano, 1996; Sines, 2003). Other studies have made use of the BASC among minority groups, such as Korean American (Jung, 2001), Chinese American (Zhou, Peverly, Xin, Huang, & Wang, 2003); African American (Serrano, 1996), and Haitian children (Ramsay, 1997).

Gender differences have been indicated in some scales of the BASC (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1998). Using the normed sample, results have showed gender differences, with boys showing higher scores in the scales of attention problems, attitude to school, attitude to teacher, atypicality, locus of control, self esteem and sensation seeking. Girls showed to have higher scores in the scales of anxiety, depression, interpersonal relations, relations with parents, sense of inadequacy and somatization. Consistent with the normative sample study, an investigation including Korean, Korean-American and Caucasian American children, found gender differences with the BASC, with boys rated and reported to be more externalizing than girls, and girls more leadership and social skills than boys (Jung, 2001). This tendency of males displaying more externalizing problems than females was also found also by Czarnecki (1996) and Stanton (1995).

In general, other gender differences have been noted in the literature. Boys and girls exhibit different approaches to handling conflicts within peer groups, which generally includes others of the same gender. Boys are more able to engage in direct confrontations and to discuss rules and issues of fairness in peer conflicts, where as girls use less direct conflict resolution strategies with their female peers (Beal, 1994; Langdale, 1993). Barnett (1986) found that male and female characters in children's storybooks were depicted as showing different styles of helping with problems, with female characters being more likely to help with an expressive style (e.g. comforting, consoling, providing emotional support) whereas male characters were more likely to provide instrumental help (e.g. actions designed to obtain a goal or overcome an obstacle).

Research objectives and questions

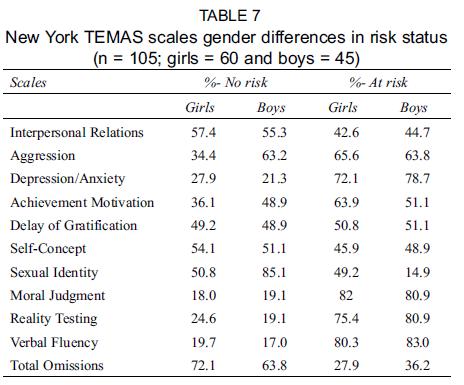

Since gender differences have been found with both the TEMAS and BASC instruments, therefore, this study attempted to explore these differences further with the TEMAS and BASC, with the additional dimension of comparing two different sites in Puerto Rico and in New York. Gender differences were examined in social problem solving skills as measured by the TEMAS, and these scale scores were then compared with levels of adjustment or maladjustment presented with the BASC. Scale scores of the TEMAS and BASC were analyzed by scale scores, and tested for sex differences by sites, in Puerto Rico and in New York City. Finally, scale scores were re-ordered according to categories consistent with a scoring system of no risk and at risk status. Both TEMAS and BASC findings are expressed in T-scores. TEMAS scale scores were categorized as no risk (t- scores from 40 on) and at risk (t- scores below 40). Clinical scales of the BASC test measure maladjustment and high scores on these scales indicate negative or impaired functioning in social relationships. T-scores of 59 or less are considered no risk, 60 to 69 are considered at-risk, and of 70 or higher are considered clinically significant.

In this study several research questions were posed while comparing Hispanic children of Puerto Rico and New York in terms of gender differences:

1. Do girls and boys show significant differences in their social problem skills as measured by the TEMAS scales?

2. Do scale scores of TEMAS show significant gender differences by site (PR vs. NY)?

3. Do girls and boys show significant differences in their risk levels for functions measured by the TEMAS and BASC?

Method

Participants

In Puerto Rico the sample selected for this study were 110 Hispanic students (45 boys and 65 girls, ages 9 to 11 (M=10.34, SD=1.41); and in New York City 105 Hispanic students (girls = 60 and boys = 45), ages 9 to 11 (M=10.26, SD=.46). Participating schools in Puerto Rico were selected from a list of active public schools from the local Department of Education. These included four schools located in the metropolitan San Juan area in Puerto Rico. Appropriate permission from the Central Board of the Department of Education and from the Institutional Review Board for protection of human subjects was obtained prior to data collection. Schools were sampled sequentially, that is, only one at a time to facilitate the logistics of the study and decrease any potential disruptions to school schedules. Recruitment procedures in New York were limited to two public schools in Brooklyn, New York City, where the Lutheran Medical Center Sunset Park Mental Health Center managed a School-based Mental Health Program. Due to restrictions of the agency, children could not be queried as per their specific ethnicity; thus, this variable could not be controlled, although Census analyses suggest that the areas sampled include a majority of low-income Puerto Ricans.

Instruments

The TEMAS instrument has a well-researched and standardized scoring system that includes norms for Puerto Rican children (ages 5- 13), both in Puerto Rico and New York. The TEMAS is composed of chromatic pictures that present conflict situations. Examinees are motivated to develop a narrative about the psychological conflict represented in the pictures that portray antithetical situations (e.g., complying with a parental request vs. continuing playing with peers; helping an elderly person carry groceries vs. harassing an elderly person). Both the content (what is told) and the structure (how the story is told) of the stories are scored.

TEMAS pictures are depicted in full colors in order to faithfully depict the settings and themes and to motivate children's attention (Costantino, 1987). TEMAS characters are depicted interacting in settings, such as: school, street, and home. There are two parallel sets of pictures for TEMAS: one for minorities and one for non-minorities. Also, there are two standard versions of the TEMAS: a long version of 23 chromatic pictures, and a short version of nine pictures.

The TEMAS short version (reported herein) takes approximately an hour to complete. The instrument is administered according to standardized instructions and structured inquiries. There are two systems for administering the TEMAS, one is the individual/oral format and another is the group/written format reported herein. This study used the group format, where children watch TEMAS pictures projected on a screen and write down a narrative on a pre-structured writing form with standardized questions.

In order to assess social problem skills, the TEMAS is comprised of nine personality functions, 18 cognitive functions and seven affective functions. The TEMAS personality scales of interest used in this study were: Interpersonal Relations, Control of Aggression, Control of Anxiety/Depression, Achievement Motivation, Delay of Gratification, Self-concept of Competence, Sexual Identity, Moral Judgment, Reality Testing; and the TEMAS cognitive scales were: Verbal Fluency, and Narrative Omissions of Characters, Events and Settings. These TEMAS variables were selected since they can be expressed in T-values and compared to the BASC scale scores which are also expressed in T-values.

The BASC has five components which may be used individually or in any combination. This study used only one of the five components, specifically the Self Report of Personality (SRP). The SRP takes about 30 minutes to complete and has forms at two age levels: child (8-11) and adolescent (12-18) (The former age level was used in this study). The developmental levels overlap considerably in scales, structure, and individual items.

This study used the Self Report of Personality Child Level (SRP-C) that has 12 scales (see Table 2). The BASC variables of interest were: Anxiety, Attitude to school, Attitude to teachers, Atipicality, Depression, Interpersonal Relations, Locus of Control, Relations with parents, Self Esteem, Self Reliance, Sense of Inadequacy, and Social Stress. These scales can be arranged into the following composites: Clinical Maladjustment, School Maladjustment, Personal Adjustment and Emotional Symptoms Index. To correct and interpret the SRP-C the computer program BASC Enhance Assist, was used, which generates profiles, calculates validity indexes, and identifies strengths and weaknesses. The SRP-C can be interpreted with reference to national age norms (General, Female, and Male) or to Clinical norms.

Procedure

During the recruitment phase children were invited to participate through their classroom teachers. Informed consent was obtained in writing from the children's parents, and assent from the children. Confidentiality was assured by identifying the participants with a code number. The permission obtained from the Department of Education did not allow gathering personal demographic information. That is why ethnicity could not be more appropriately controlled. Only the Project Director had access to the master list linking only the names, age and sex of the students to code numbers.

Testing was administered in the community schools during regular hours in classrooms or in the library. Research assistants were assigned to each group administration. In Puerto Rico, the test was administered in Spanish, whereas in New York City, the Hispanic children used English or Spanish according to their preference. Graduate clinical psychology students supervised by the project director conducted the testing and scoring. Protocols were scored completely blind. This type of research did not seem to pose risks to participants and no adverse reactions among the children were noted. The inter-rater reliability of the TEMAS scales was assessed by comparing the scores independently given by the researcher with those given by another clinician, both trained in the TEMAS administration and scoring system (adequate reliabilities from .73 to .87 were obtained). Reliability was not calculated for Verbal Fluency since it required a simple word count. To correct and interpret the SRP-C the computer program BASC Enhance ASSIST was used, which generates profiles, calculates validity indexes, identifies strengths and weaknesses and computes multi-rater comparisons.

For this cross-sectional study, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine gender differences for the TEMAS and BASC scales. Statistical significance was determined by p=.05. All data was analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software (SPSS) version 13.0.

Results

In Puerto Rico, all participants presented their stories in Spanish; but in the New York sample, 87 children (80.6%) responded in English while 21 children (19.4%) responded in Spanish. In New York, children who responded in Spanish had significantly higher verbal fluency in the TEMAS stories than the children who responded in English [F (1, 106) = 7.663, p = .007, h2 = .07]. Therefore, children were at a disadvantage when producing their stories in a second language.

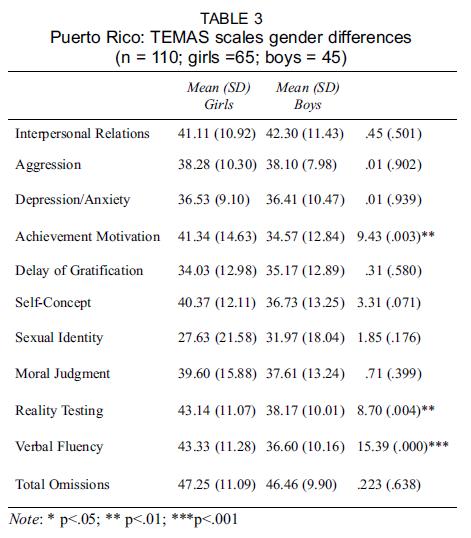

In Puerto Rico, three TEMAS scales showed significant gender differences in favor of girls: Achievement Motivation, Reality Testing and Verbal Fluency (refer to Table 3). Also, girls showed a tendency toward significance in higher self concept of competence than boys. Girls in the sample from Puerto Rico showed maladaptive skills in the areas of control of Aggression, control of Depression/Anxiety, Delay of Gratification, Sexual Identity, and Moral Judgment. Boys showed maladaptive skills in the areas of control of Aggression, Control of Depression/Anxiety, Achievement Motivation, Delay of Gratification, Self Concept, Sexual Identity, Moral Judgment, Reality Testing, and Verbal Fluency.

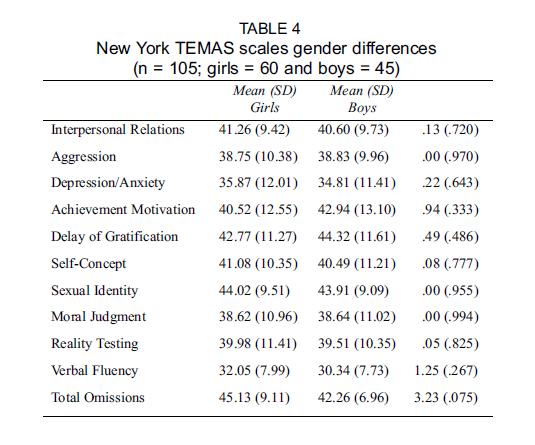

In New York, there were no significant gender differences with the TEMAS scales (refer to Table 4). However, one scale showed a marginal significance (Total Omissions). In the New York sample, Hispanic girls showed maladaptive skills in the areas of control of Aggression, control of Depression/Anxiety, Moral Judgment, Reality Testing, and Verbal Fluency. Boys showed maladaptive skills in Aggression, Depression/Anxiety, Moral Judgment, Reality Testing, and Verbal Fluency.

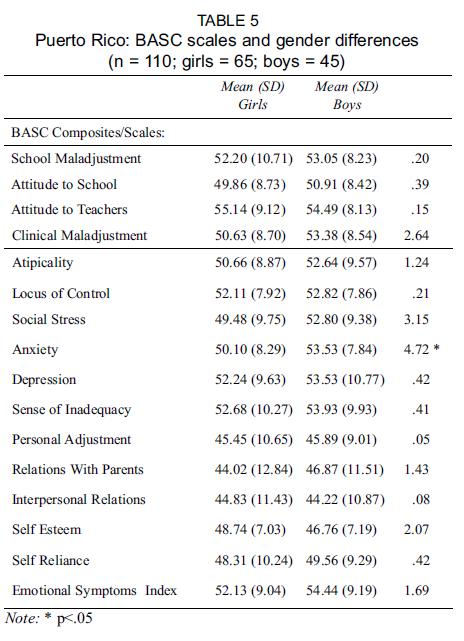

In Puerto Rico, only one BASC scale showed significant gender differences, the Anxiety scale, showing that girls have a more adaptive control of anxiety (refer to Table 5); while no significant differences were found in the New York sample.

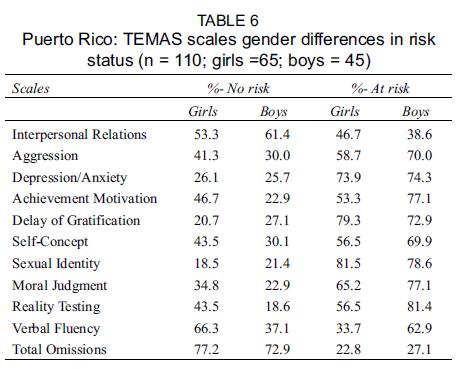

With the TEMAS, as can be seen in Tables 6 and 7, in Puerto Rico about three quarters of boys and girls seems at risk for maladjustment, when attempting to resolve conflicts that require skills controlling Anxiety/depression, Delay of gratification and Sexual identity. In New York, about three quarters of the sample including boys and girls seems at risk for maladjustment, when attempting to resolve conflicts that require skills controlling Depression/anxiety, Moral judgment, Reality testing. Therefore, both in Puerto Rico and in New York Hispanic boys and girls appear remarkably at risk when dealing with situations that may induce depression/anxiety. Limited English Proficiency as reflected in poor verbal fluency sets Hispanic children in NY at risk.

Discussion

In Puerto Rico, Hispanic girls were more fluent verbally when developing narratives about conflict situations. In NY both girls and boys showed problems with verbal fluency (below age expectation), hence, no significant differences were found. Relative lower verbal fluency for samples in NY may be related to their limited English proficiency status. As stated by previous research with the TEMAS, children responding in Spanish exhibit higher verbal fluency than when attempting to produce their stories in English (Costantino & Malgady, 1983; Costantino, Malgady, & Vázquez, 1981). Since length of neither stay nor acculturation status was controlled, the question remains as to whether girls that respond in Spanish show higher verbal fluency than boys.

Gender differences in verbal fluency are congruent with findings indicating that in terms of narrative ability, as early as in pre-school girls are more verbal and adept at producing coherent narratives (Fiorentino & Howe, 2004). Nevertheless, as reviewed by Hyde (1990), although some studies favor females in verbal abilities; recent findings using meta-analyses have not found such differences. In turn, lower verbal fluency for boys could be related to what Pollack (1998) described as the "Code of men", an unwritten list of social beliefs about how the young men must act and behave. This social code requires that the men act strong, do not show their feelings and inhibit the verbal expression of their experiences when faced with frustration or difficulty.

Given the advantage of females in verbal fluency and school grades, it is beneficial to look more closely at cross-cultural samples to determine if gender plays a role in other cognitive skills. For instance, in a previous report of a TEMAS study in Puerto Rico (with a larger sample size and covering a wider age range 9-15) showed significant differences between boys and girls in story transformations [F (1, 160), = 7.018, p .009, n2= .04], with boys making more story transformation than girls, which is another cognitive indicator where girls perform better than boys (Cardalda, Costantino, Jiménez-Suárez, León- Velázquez, Martínez, & Ortiz-Vargas, 2011).

Higher grades, robust cognitive skills, and more adaptive self concept of competence and achievement motivation for girls may suggest protective factors geared to maintain competence in school environments. But despite these relative strengths, educational disparities persist as the graduation rate for Latinas is lower than for girls in any other racial or ethnic group in the US (Ginorio & Huston, 2001). Therefore, the question remains, how females use skills to their advantage in school and whether these effects may taper off developmentally. For instance, how do cognitive skills interact with the potential for emotional problems such as depression and anxiety? Several studies have pointed out that depression is an area of mental health disparities between Hispanic and other groups of children. Canino, Gould, Prupis, and Schafer (1986) found that Hispanic children and adolescents reported more depression and anxiety symptoms than Blacks and this is consistent with a nation-wide epidemiological study that reported that Hispanics had the highest rates of depression and other affective disorders, and higher co-morbidity, compared to any other ethnic groups (Kessler et al., 1994). Other depression studies have showed that Hispanic adolescents express somatic complaints more prominently than Whites and Blacks (Roberts, 1992).

There are however, some limitations of this study. Only public schools were used in these comparisons. Children from private schools as well and SES contributions to mental health need to be considered in order to interpret specific patterns. Another question is what can happen if the group testing format is administered in other sites in the United States. Inter-rater reliability was not calculated although consensus for scoring and double-checking by others was followed. Finally, due to the kind of permission obtained from the Department of Education, personal demographic information or identification of the children could not be collected in any way, and ethnicity could not be controlled. Future recommendations for similar studies include examining specific populations and age groups of Hispanic/Latino children; in order to evaluate risk and protective factors to consider what works and does not work with these minority at risk groups.

REFERENCIAS

Barnett, M.A. (1986). Sex bias in the helping behavior presented in children's picture books. Journal of Generic Psychology, 147, 343-351. [ Links ]

Beal, C.R. (1994). Boys and Girls: the development of gender roles. New York, McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Bernal, I. (1991). The relationship between level of acculturation, the Robert's Apperception Test for children, and the TEMAS: Tell- Me-A-Story. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, School of Professional Psychology, Los Angeles, CA. [ Links ]

Cámara Fuertes, L.R. (n.d.). Breve radiografía de la educación superior en Puerto Rico. División de Investigación y Documentación de la Educación Superior. Retrieved from www.gobierno.pr/NR/rdonlyres/256BCAD [ Links ]

Canino, I.A., Gould, M.S., Prupis, M.A., & Shafer, D. (1986). A comparison of symptoms and diagnoses in Hispanic and Black children in an outpatient mental health clinic. Journal of American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 25, 254-259. [ Links ]

Cardalda, E. B. (1995). Socio-cognitive correlates to school achievement using the TEMAS (Tell-Me-A-Story) culturally sensitive test with sixth, seventh and eighth grade. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The New School for Social Research, New York, New York. [ Links ]

Cardalda, E.B., Costantino, G., Jiménez-Suárez, V., León-Velázquez, M., Martínez, J.V., & Ortiz-Vargas, N. (2011). Cross-cultural comparisons of the TEMAS group and individual testing format. Unpublished manuscript. [ Links ]

Cardalda, E.B., Costantino, G., Martínez, J.V., León-Velázquez, M., Jiménez-Suárez, V., & Ortiz-Vargas, N. (2011). Cross cultural comparisons of the TEMAS projective/narrative test with the BASC self report of personality. Unpublished manuscript. [ Links ]

Cardalda, E. B., Costantino, G., Ortiz-Vargas, N., León-Velázquez, M., & Jiménez Suárez, V. (2007). Relationships between the TEMAS test and school achievement measures in Puerto Rican children. Ciencias de la Conducta, 22, (1), 79-102. [ Links ]

Cardalda, E. B., Costantino, G., Sayers, S., Machado, W., & Guzmán, L. (2002). Use of TEMAS with patients referred for sexual abuse: Case studies of Puerto Rican children. Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 13, 167-183. [ Links ]

Cardalda, E.B. Figueroa, M., Hernández, M., Rodríguez, N., Martínez, J., Costantino, G., Jiménez-Suárez, V., & León, M. (2008). Interpreting the TEMAS verbal fluency scale relative to language problems in Puerto Rican high risk children. In J.R. Rodríguez Gómez (Ed), Antología de Investigaciones de los Programas Académicos de la Universidad Carlos Albizu, (pp. 269-286). Hato Rey, PR: Publicaciones Puertorriqueñas. [ Links ]

Cornabuci, C. (2000). Relationship between aggression and interpersonal relations in 7 and 8 years old Italian children. Unpublished dissertation, Universita di Roma "La Sapienza", Rome, Italy. [ Links ]

Costantino, G. (1987). TEMAS (Tell-Me-A-Story) cards. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [ Links ]

Costantino, G., Dana, R. & Malgady, R. (2007). TEMAS (Tell-Me-AStory) assessment in multicultural societies. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Costantino, G. & Malgady, R. (2000). Multicultural and cross-cultural utility of TEMAS (Tell-Me-A-Story) test. In R.H. Dana (Ed.), Handbook of Cross-Cultural/Multicultural Personality Assessment (pp. 393-417). Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Costantino, G. & Malgady, R. (1983). Verbal fluency of Hispanic, Black and White children on TAT and TEMAS, a new thematic apperception test. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 5 (2), 199-206. [ Links ]

Costantino, G., Malgady, R., Casullo, M., & Castillo, A. (1991). Cross-cultural standardization of TEMAS in three Hispanic subcultures. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 13 (1), 48-62. [ Links ]

Costantino, G., Malgady R., Colon-Malgady, G., & Bailey, J. (1992). Clinical utility of the TEMAS with nonminority children. Journal of Personality Assessment, 59 (3), 433-438. [ Links ]

Costantino, G., Malgady, R., & Faiola, T. (1997, July). Cross-cultural standardization of TEMAS with Argentinean and Peruvian children. ICP Cross-Cultural Conference, Padua, Italy. [ Links ]

Costantino, G., Malgady, R., & Rogler, L. (1988). TEMAS (Tell-Me- A-Story) manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [ Links ]

Costantino, G., Malgady R., Rogler, L., & Tsui, E. (1988). Discriminant analysis of clinical outpatients and public school children by TEMAS: A thematic apperception test for Hispanics and Blacks. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52 (4), 670-678. [ Links ]

Costantino, G., Malgady, R., & Vázquez, C. (1981). A comparison of the Murray-TAT and a new thematic apperception test for urban children. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 3 (3), 291-300. [ Links ]

Costantino, G, Rand, M., Malgady, R., Maron, N., Borges-Costantino, M., & Rodríguez, O. (1994, August). Clinical differences in sexually abused and sexually abusing African-American, Hispanic and White children. Paper presented at the 102nd Convention of the American Psychological Association, Los Angeles, CA. [ Links ]

Czarnecki, C.A. (1996). Relationship of age, time since parental separation and remarriage with academic adjustment in children. [Abstract]. Dissertation Abstracts International, 57, 0576. Hofstra U., US. [ Links ]

Dulin, J. (2001). Teacher ratings of early elementary students'socialemotional behavior. [Abstract]. Dissertation Abstracts International, 61, 3469. U Georgia, US. [ Links ]

Dupertuis , D, G, Silva Arancibia, V, Pais, E., Fernández, C., & Rodino, V. (2001, July). Similarities and Differences in TEMAS Test Functions in Argentinean and European- American children. Paper presented at the VII European Congress of Psychology, London, England [ Links ]

Fantini, F., Aschieri, F., Bevilacqua, P., & Augello, C. (2007, July). TEMAS. Multicultural validity and clinical utility in Italy. Paper presented at the 10th European Congress of Psychology, Prague. [ Links ]

Fiorentino, L. & Howe, N. (2004). Language competence, narrative ability, and school readiness in low-income preschool children. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 36, 280-294. [ Links ]

Flanagan, R. (1995). A review of the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC): Assessment consistent with the requirements of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Journal of School Psychology, 33 (2), 177-186. [ Links ]

Frontera-Benvenutti, R. (1992). A Comparison of two independent Spanish translations for the student questionnaire of the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC). [Abstract]. Dissertation Abstracts International, 52, 5014. Texas A & M U, US. [ Links ]

Ginorio, A. & Huston, M. (2001) Si se puede, Yes we can! Latinas in School. Retrieved from www.aauw.org. [ Links ]

Gladman, M. & Lancaster, S. (2003). A review of the Behaviour Assessment System for Children. School Psychology International, 24 (3), 276-291. [ Links ]

Hyde, J.S. (1990). Meta-analysis and the psychology of gender differences. Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 16, 55- 73. [ Links ]

Jung, W. (2001). Cultural influences on ratings of behavioral and emotional problems, and school adjustment for Korean, Korean American, and Caucasian American children. [Abstract]. Dissertation Abstracts International. 61, 3465. Oklahama State U, US. [ Links ]

Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, K. A., Zhao, S., & Nelson, C. B. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8-19. [ Links ]

Krinsky, R., Costantino, G., & Malgady, R. (1999, August). Delay of gratification, achievement- motivation, and aggression among minority children of polysubstance abusers. Paper presented at the 107th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Langdale, S. (1993). Moral development, gender identity, and peer relationships in early and middle childhood. In A. Garrod (Ed.), Approaches to Moral Development: New research and emerging themes (pp. 30-58). New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Malgady, R., Costantino, G., & Rogler, L. (1984). Development of a Thematic Apperception Test (TEMAS) for urban Hispanic children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52 (6), 986-996. [ Links ]

McCloskey, D., Hess, R., & D'Ámato, R. (2003). Evaluating the utility of the Spanish version of the Behavior Assessment System for Children-Parent Report System. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 21 (4), 325-337. [ Links ]

Merenda, P. (1996). BASC: Behavior Assessment System for Children. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 28 (4), 229-232. [ Links ]

Millán-Arzuaga, F. (1990). Mother-child differences in values and acculturation: Their effect on achievement motivation and selfconcept in Hispanic children. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, New York. [ Links ]

Pollack, W. (1998). Real Boys: Rescuing our sons from the myths of boyhood. New York: Henry. [ Links ]

The Condition of Education. (1995). Progress in the achievement and attainment of Hispanic students. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/pubs/CondOfEd_95/ovw2.html [ Links ]

Ramsay, B. (1997). Standardization of the Roberts Apperception Test with Haitian children. [Abstract]. Dissertation Abstracts International, 58, 0838, Caribbean Center for Advanced Studies, US. [ Links ]

Reynolds, C. & Kamphaus, R. (1998). BASC. Behavior Assessment System for Children Manual. MN: American Guidance Service. [ Links ]

Rios Orlandi, E. (2005). Los estudios de postgrado en Puerto Rico. Primer informe oficial. Universidad de Puerto Rico. Retreived from www.universia.pr/pdf/unescogestion/ [ Links ]

Roberts, R. E. (1992). Manifestation of depressive symptoms among adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 180, 627-633. [ Links ]

Sandoval, J., & Echandia, A. (1994). Behavior Assessment System for Children. Journal of School Psychology, 32, 419-425. [ Links ]

Sanjurjo Meléndez, L. (2006, July 8). Alarma la cifra de estudiantes que fracasan. El Nuevo Dia, 6. [ Links ]

Sardi, G.M, Summo, B., Carnabuchi, C., & Sulfaro, C. (2001, July). Relationship between Aggression, Cognition and Moral Judgement in conflict resolution among Italian children. Paper presented by E. Costantino at the VII European Congress of Psychology, London, England. [ Links ]

Serrano, C. (1996). Inter-rater reliability of aggression among three ethnic groups. [Abstract]. Dissertation Abstracts International, 57, 4086. Texas A & M U, US. [ Links ]

Sines, M. (2003). A comparison of the psychological functioning of sexually abused Mexican-American and non-Hispanic White children and adolescents. [Abstract]. Dissertation Abstracts International, 63, 3939. Texas A & M U., US. [ Links ]

Stanton, S. (1995). Clinical and adaptive features of children and adolescents who have an emotional disturbance. [Abstract]. Dissertation Abstracts International, 56, 3465. Texas A & M U., US. [ Links ]

Sulfaro, C. (2000). Relationship between aggression and moral judgment. Unpublished dissertation, Universita di Roma "La Sapienza", Rome, Italy. [ Links ]

Summo, B. (2000). Relationship between aggression and emotional functions in conflict resolution of 7 and 8 years old children. Unpublished dissertation, Universita di Roma "La Sapienza", Rome, Italy. [ Links ]

Walton, J.R., Nuttall, R.L., & Vázquez-Nuttall, E. (1997). The impact of war on the mental health of children: A Salvadoran study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21, 737-749. [ Links ]

Yang, C., Kuo, L., & Costantino G. (2003, July). Validity of Asian TEMAS in Taiwanese children: Preliminary data. Paper presented at the European Congress of Psychology, Vienna, Austria. [ Links ]

Zhou, Z., Peverly, S., Xin, T., Huang A., & Wang, W. (2003). School adjustment of first-generation Chinese-American adolescents. Psychology in the schools, 40 (1), 71-84. [ Links ]

Authors note: Based on a paper originally presented at the European Congress of Psychology, July, 2007, Prague, Czech Republic.

Acknowledgments: This paper is based on the findings of the study "Evaluation of the effectiveness of narrative techniques in the assessment of mental disorders symptomatology and coping skills of Hispanic children at high risk of mental disorders conducted from 2003-2005, at the Center for Research and Outreach in Hispanic Mental Health and other Health Disparities National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (CROHMOD) (Grant Number- 1 R24 MD00152-01).

1Nota: Este artículo fue sometido a evaluación en enero de 2010 y aceptado para publicación en marzo de 2011.

22Toda comunicación de este trabajo debe hacerse a la primera autora a la siguiente dirección: Calle Tanca #300, Suite 3D, San Juan, PR, 00901. E-mail:

ecardalda@gmail.com