Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Journal of Human Growth and Development

versão impressa ISSN 0104-1282versão On-line ISSN 2175-3598

J. Hum. Growth Dev. vol.28 no.1 São Paulo jan./mar. 2018

https://doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.143856

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Knowledge and acceptance of HPV vaccine among adolescents, parents and health professionals: construct development for collection and database composition

Priscila Dantas Leite e SousaI; Albertina Duarte TakiutiII; Edmund Chada BaracatII; Isabel Cristina Esposito SorpresoI, II; Luiz Carlos de AbreuI

ILaboratório de Delineamento de Estudo e Escrita Científica, Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André- SP- Brasil

IIDisciplina de Ginecologia da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (USP)- São Paulo- Brasil

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The human papillomavirus (HPV) is a prevalent viral infection in the sexually active population, which can be oncogenic and non-oncogenic. Educational efforts by health professionals, aimed at adolescents and their parents, help decision-making on human papillomavirus vaccination, benefiting the implantation process and vaccine coverage.

OBJECTIVE: To describe the data collection constructs about knowledge and acceptability of HPV vaccine among adolescents, parents and health professionals.

METHODS: Study of construct elaboration based on an empirical review of the literature with a qualitative focus on PubMed database, from 2007 to 2014, using the following keywords: Papillomaviridae AND Papillomavirus Vaccines AND Knowledge AND Community Health Services. A total of 31 questions were divided into six categories. In the internal validation, the final construct was applied in 390 subjects (adolescents, parents/guardians and health professionals) in the period of 2014. The proportion of assertive responses and respective 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to describe each question.

RESULTS: Three articles on the subject were found in the databases consulted that served as the basis for the elaboration of the questionnaire. There was a lower proportion of correct answers among adolescents about knowledge of HPV. Adolescents, parents, and carers showed a low proportion of correctness about the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. The three groups did not show any barriers to vaccine acceptability.

CONCLUSION: The instrument was adequate to measure knowledge about HPV, its repercussions and its vaccine among adolescents, parents/guardians and health professionals, as well as measuring the acceptability of the human papillomavirus vaccine.

Keywords: HPV, papillomavirus vaccines, knowledge, adolescent, parents, health-care professional, surveys and questionnaires.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a prevalent viral infection in the sexually active population, which can be oncogenic and non-oncogenic. The most cited oncogenic types are the 16 and 18 related to cancers of the uterus, anus, penis, vagina, mouth, among others. Non-oncogenes (6 and 11) have repercussions on women's health, such as anogenital warts1,2.

Cervical cancer affects women with an incidence of 16,340 cases in Brazil in 2016. This proportion of approximately 15.85 cases per 100,000 women represents a public health problem.3 The quadrivalent vaccine for HPV (6,11,16 and 18) is considered to be one of the strategies to reduce cervical cancer2,3, with protection of between 80-100% vaccinates for anogenital warts and 60-80% in reducing new cases of pre-malignant lesions2,4.

In Brazil, since 2014, the vaccine has been adopted in the National Immunization Program (PNI), targeting female adolescents from 9 to 13 years old5. The process of implantation and adequate vaccination coverage depends on the population's knowledge about HPV and its repercussions on health, as well as an integrated approach among adolescents, parents and health professionals6,7.

Kwan et al.8 and Kornfeld et al.9 provide information on barriers to acceptance, knowledge gaps and public opinion on HPV and its vaccine through collection tools on the subject. In Brazil, Figueroa-Downing et al.10 and Osis et al.11 used a collection tool developed to describe the knowledge and attitudes of health professionals10 and the lay population11.

Collection instruments elaborated for situational analysis, although not generalizable, are exploratory in the sense of providing knowledge about a certain theme. The creation of a construct through descriptive research facilitates the operation of data collection and the use of the same data for analysis and value judgment12. In addition, the search for an HPV-based construct and its vaccine allows us to characterize the acceptance status of the population as well as the parents' admissibility in deciding to vaccinate their children.

Thus, the objective of this research is to describe the construct of data collection on knowledge and acceptability of HPV vaccine among adolescents, parents and health professionals.

METHODS

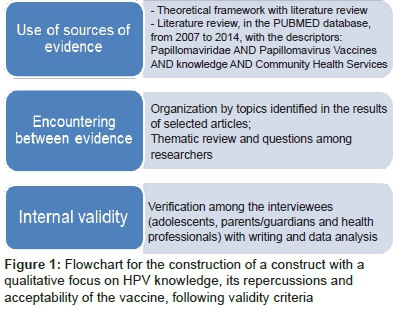

It is an instrument elaborated according to the criteria of validity of the construct with qualitative approach13,14 (Figure 1):

Use of sources of evidence

An empirical literature review was carried out in the PubMed database from 2007 to 2014, with the following descriptors present in the MEsH terms: Papillomaviridae AND Papillomavirus Vaccines AND Knowledge AND Community Health Services. The inclusion criteria were: original articles on HPV and quadrivalent vaccine, as well as approach to construction and/or instrument use with questions about knowledge of HPV and its vaccine. Review articles, bivalent and non-validated HPV vaccine articles were excluded.

The selection method was reading the title and abstract. At the end of the selection, the articles used and subsidized to the preparation of an instrument on the knowledge of HPV, the vaccine and its acceptance among adolescents, parents and/or carers and health professionals.

Encounter between evidence13,14

This is a process of organization by theme in the results of the selected articles and a review of the themes and issues between researchers regarding the identification of relevant conclusions, contributing to the construction of the instrument on the knowledge of HPV and its vaccine.

Identification of the thematic

Organization by themes identified in the results of the selected articles, are shown in Table 1.

Review of report by researchers

A questionnaire was composed of 24 questions related to the knowledge and acceptability of HPV and its vaccine. The instrument was presented for consensus among specialists to complement and suggest changes.

The questionnaire was prepared and adapted four times before the definitive model was formulated. After consensus among experts, the questionnaire had 26 questions. Abbreviations were withdrawn. It was decided to put 'no response' on issues aimed at women with a history of cervical cancer and health professionals, rather than as a "no-holds" or "no opinion" answers. Three questions were raised about vaccine safety, the source of knowledge about the HPV vaccine, and whether the subject had already received the vaccine.

Specifically for health professionals, two questions were raised: whether patients living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can be vaccinated and whether the vaccine is safe for pregnant women. The aim was to obtain a self-administered instrument.

The final instrument for data collection (Figure 2) was composed of 31 questions divided into six categories: 1) knowledge about HPV (7 questions); 2) knowledge about the HPV vaccine (11 questions); 3) vaccination barriers for HPV (3 questions); 4) acceptability of HPV vaccine (3 questions); 5) personal history related to HPV infection in female subjects (3 questions); 6) specific knowledge issues addressed to health professionals (4 questions).

The response options for the instrument questions were: yes (S); no (N); not sure (NTC). In order to score the answers, a grouping of the questions by themes was done, assigning (0) to the non-correct and (1) to the correctness of each question. There was a reversal of scores in questions 11, 12, 19 and 31. The proportion of correct responses and respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to describe the proportion of correctness for each question and the knowledge and acceptability of the HPV vaccine.

Internal validity

Verification among the interviewees (adolescents, parents/guardians and health professionals) with writing and data analysis are shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Cultural adaptation of the instrument

A total of 390 individuals were selected by convenience sample, of which 219 were adolescents (10 to 19 years old)15, were parents or guardians (aged over 20 years) and 27 were health professionals. The study was carried out at the Casa do Adolescente of Pinheiros, in the city of São Paulo, SES/SP, in January 2014, with approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo (205/14).

For cultural adaptation of the instrument, problems of comprehensibility of the domains were identified and then a satisfactory index of knowledge for each domain of 80% was stipulated. In the application of the construct, there were no restrictions regarding sexual activity, colour, education and socio-economic level. Individuals who needed the presence of a companion during the interview and who did not understand the Portuguese language were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

The data collected was tabulated using Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. Data were used to describe the data: absolute and relative frequencies and interval estimates (95% CI) of the ratio of correct answers. The absolute sampling error was 5%. The analyses were carried out in the Stata® 11.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, EUA).

RESULTS

Three articles16-18 were found about the subject in the databases consulted. The applicability of the construct was observed in three distinct regions, one in Canada, one in China and one in Italy (Table 1).

Regarding the application of the construct, 390 participants were interviewed, 79.7% (n = 311) were males and 20.3% were (n = 79) females. The sample was made of 56.2% (n = 219) adolescents, 36.9% (n = 144) parents and/guardians and health professionals 6.9% (n = 27). The questionnaire was applied during interviews, answered individually by the interviewees, in a calm and private environment.

After data collection, there was a moment of open discussion among researchers and interviewees about actions that could be taken regarding health promotion and counselling on HPV and its repercussions, as well as regarding HPV vaccine in population health.

Interviewees presented difficulties in understanding the confounding issues between HPV (human papilloma virus) and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). There was also a need to exchange terms from the 'cervical oncology colpocytology examination' to 'Pap' (popular terminology), as well as using the colloquial term 'Pap changes' rather than the technical term 'high or low intraepithelial neoplastic grade' or 'low- and high-grade intraepithelial lesion'.

In Table 2, regarding the perception about HPV knowledge and its repercussions on health, a lower proportion of correctness was identified, especially among adolescents, for the following questions: What is HPV?' 60.7% (CI 53.9, 67.2); 'Is it a virus?' 68.9% (IC 62.4, 75.0); 'Is it a sexually transmitted disease?' 47.0% (CI 40.3, 53.9); 'Is it related to cervical cancer? 66.7% (CI 60.0; 72.9); 'Can HPV cause changes in the Pap?' 50.2% (CI 43.4; 57.0) and 'Is cervical cancer a major cancer in women?' 64.4% (CI 57; 7.70-7.7). Smoking was not perceived as a risk for cervical cancer among the interviewees, with 47.5% (CI 40.7; 54.3) of adolescents, 60.5% (CI 52.2; 68.5) of parents/guardians, 59.3% (CI 38.8; 77.6) of health professionals.

In Table 3, the perception of knowledge about HPV vaccine as a form of cervical cancer prevention was shown to have a high level of correctness, with 80.4%(CI 77.5; 85.4) for adolescents, 88.4% (CI 82.1; 93.1) for parents/guardians and 81.5% (CI 61.9; 93.7) for health professionals. The timing to be vaccinated had a lower proportion of correctness among adolescents, 65.8% (CI 59.1; 72.0), also 52.1% (CI 45.2; 58.8) of them perceived that it was not necessary to be vaccinated before the beginning of sexual intercourse.

Adolescents and parents/guardians showed a lower proportion of correct responses 10.0% (CI 6.4; 14.8) and 10.2% (CI 5.8; 16.3), respectively, on the vaccine being harmful to health. The proportion of wrong answers was higher among adolescents in the following questions: 'Can the HPV vaccine cause HPV infection?' 44.7% (CI 38.0; 51.6); 'Is the HPV vaccine provided by the government?' 63.9% (CI 57.2; 70.3)', 'Is the HPV vaccine part of the girls' immunization record?' 53.0% (CI 46.1; 59.7), 'Are 3 doses required for complete vaccination?' 42.9% (CI 36.3; 49.8) and 'Does the HPV vaccine decrease the chances of having genital warts?' 32.4% (CI 26.3; 39.1).

Adolescents, parents and health professionals had a low proportion of correct responses when questioned about the efficacy of the HPV vaccine in reducing precursor lesions of cervical cancer with 22.4% (CI 17.0; 28.5), 34.7% (CI 27.0; 43.0) and 51, 8% (CI 31.9; 71.3), respectively.

In Table 4, the parents/guardians were identified as having fewer propensities for assertive responses regarding vaccine acceptance on the following questions: 'Do you know anyone who has ever had the HPV vaccine?' 38.8% (CI 30.9; 47.2) and 'Have you received the HPV vaccine?' 9.5% (CI 5.3; 15.5). They would recommend the vaccine for their own children, friend or relative in 90.5% (CI 84.5; 94.7).

DISCUSSION

The elaboration of an instrument for collecting data on HPV knowledge and acceptability of the vaccine based on an empirical review of the literature with a qualitative approach allows the analysis of the perception of the subject, the measurement of the knowledge about HPV, its repercussions and its vaccine among adolescents, parents/guardians and health professionals, as well as measuring the acceptability of the vaccine.

Knowledge and acceptability research of the HPV vaccine aims to understand the cultural aspects and knowledge of the population about vaccination for better adherence and territorial vaccine coverage.

The results of the qualitative review of the literature identified articles that address the use of health tools to explore the themes 'HPV' and 'HPV vaccine' in different populations. Giambi et al.16 developed a questionnaire containing 23 items, divided into 9 categories: demographic and behavioural information; vaccination; barriers and reasons for non-vaccination; knowledge of HPV; source of information about HPV; perception of risk that their daughter could contract HPV; intention of future vaccination; counselling of health professionals consulted on HPV vaccination. In the same study, 1738 relatives of unvaccinated girls were interviewed to explore barriers to vaccination in Italy.

Rosberger et al.18 investigated the effect of a workshop on HPV and its vaccine among employees of a community health and social service agency in Montreal, Canada, where participants responded to 20 items that measure HPV knowledge before and after the workshop. The questionnaire contained topics on confidence in the ability to provide accurate information to parents and on the HPV vaccine recommendation for daughters and nieces, as well as items assessing beliefs about possible barriers to HPV vaccine.

Fu et al.17 evaluated medical students' knowledge about HPV and HPV-related diseases, as well as the intention of vaccinating this population through an instrument addressing socio-demographic information, such as age, gender, ethnicity and degree of knowledge about HPV, cervical cancer, genital warts and HPV vaccines and their own perceptions on the theme.

The synthesis of the three articles identified from the descriptors allowed the definition of the categorizing topics to be approached, such as knowledge about HPV, about the HPV vaccine, barriers to vaccine acceptance and specific awareness among health professionals.

Giambi et al.16 emphasize the importance of exploring vaccination acceptance barriers in the families of unvaccinated Italian girls, such as fear of adverse events and vaccine safety in developing HPV-induced lesions. Rosberger et al.18 demonstrated that health education among health professionals with specific topics being covered regarding the HPV vaccine brought greater reliability in providing information and recommending the vaccine among professionals.

Knowledge about HPV, cervical cancer, genital warts and HPV vaccines, as well as perceptions of vaccination were evaluated by Fu et al.17. In this study, the influence of the female sex on the knowledge and acceptance of the HPV vaccine was shown to be higher in the intention to vaccinate. All of those related health factors vary in the general population according to sex, age and educational level11,19,20.

The collected and analysed collection instrument indicates a lower proportion of correct answers in the categories 'HPV knowledge' and 'vaccine acceptability' among the adolescents interviewed, followed by parents/guardians and health professionals, being "knowledge gaps about HPV and its repercussions on health" health education topics to be addressed in each population.

In turn, adolescence is a period marked by biopsychosocial changes and emotional instability, which arouses in adolescents the desire to experience new experiences, often in a rash manner, such as unprotected sex. Due to this condition of development and exposure, they are vulnerable, becoming exposed to, for example, sexually transmitted diseases, thus requiring physical, psychological and social protection from the family, school and community21,22.

Knowledge about HPV was considered low among adolescents from several countries23,24, a common finding evidenced by the construct. This finding corroborates the need to reaffirm the importance of sex education programmes and the provision of information on the disease and vaccine.

The construct, through questions related to the subject 'knowledge of HPV and its clinical repercussions', showed a lower propensity to learn about the relation between smoking and the risk of developing cervical cancer. Tobacco is the second most commonly used drug among young people in the world25, so discouraging them from use is a public health challenge.

In addition, joint actions of promotion and prevention combining the themes of HPV and smoking, especially among adolescents, should be encouraged, since tobacco is also a cofactor in the development of cervical cancer and interferes with the immunity of young women26.

Adolescents perceived the vaccine to be a primary form of prevention of cervical cancer and saw the importance of administration prior to first sexual contact when questioned in the construct about the relationship between HPV, cervical cancer and sexual activity. Kilic et al.6 have identified that the motive and interest in receiving the vaccine is related to the protection against HPV and cervical cancer. However, Kwan et al.8 demonstrated that a low knowledge and understanding about the prevention and disease process of HPV and the vaccine was paradoxically good for the acceptance of the vaccine process.

In Latin American reports, adolescents demonstrated an interest in the HPV vaccine, although they considered the vaccine to be new technology and lacked specific information about it. In addition, the acceptance of the vaccine was related to the age group and the presence of sexual activity27.

Acceptance barriers in the target population (adolescents)27 and refusal to vaccinate exist due to factors such as fear of experiencing pain during the application, fear of family disapproval, uncertainty about vaccine efficacy8,28. Lack of adequate information and myths regarding HPV infection can lead to the over-evaluation of the vaccine and affect the perception of the importance of surveillance against cervical cancer8.

The vaccine knowledge gap regarding its safety and its preventive action against precursor lesions and genital warts27 are perceptions identified by the construct among those adolescents interviewed.

The problem of vaccine acceptance should be viewed as a network with varying levels of complexity: social and racial inequality has a direct influence on many health issues and is not different29. Family support and a shared decision should always be preferred to simple government imposition24.

Parents' knowledge about HPV and its repercussions on the health of adolescents, sons and daughters, is fundamental for the acceptance of the vaccine9. The decision of whether to be vaccinated or not is influenced by parents and family members, especially in the earliest target population6. Many parents are against vaccination for fear of possible side effects and there is therefore a lack of knowledge about the safety and positive impact of the vaccine on the health of their children9.

After the introduction of the vaccine in national immunization programmes, studies have shown greater acceptability to the vaccine in other countries30,31. However, in British Columbia (Canada), even with public funding and vaccination in schools, 35% of parents decided not to vaccinate their daughters. The main reasons reported were concerns about vaccine safety, intent to wait until their daughter was older, and not having enough information about the vaccine32.

The construct (Figure 2) demonstrated that parents and carers are informed about the existence of the HPV vaccine and are in favour of its implementation and the government's initiative to vaccinate their daughters. A regional study in our country observed that there were no difficulties in accepting the vaccine in our country33, which is corroborated bythe interviewees.

Knowledge about the viral origin of HPV and its involvement with cervical cancer, as well as it being sexually transmissible and causing changes in the cervical oncology cytology were themes identified through the elaborated construct. The postponement of vaccination is a vaccination barrier related to knowledge about the vaccine and HPV33, as well as knowledge gaps regarding HPV infections and their relation to cervical cancer34, and these have repercussions, such as postponing vaccination for their children.

Another barrier to acceptance of common vaccination is the myth among parents that vaccination may lead to early or promiscuous sexual activity, increasing the number of sexual partners and also negatively affecting condom use35. Conversely, the parents interviewed (Tables 2 to 4) were accepting of the vaccine and showed no sign of believing the myths related to the early onset of sexual activity.

The construct revealed doubts about the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine, especially among the parents interviewed in the study (Table 3). Albright et al.36 demonstrated similar doubts regarding the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, which was reflected in the decision of these parents to postpone the vaccination of their daughters until its effectiveness was proven. Cheruvu et al.37 show that parents did not intend to vaccinate their daughters because of safety concerns and Figueroa-Downing et al.10 also found knowledge gaps related to vaccine safety in their study.

Regarding the efficacy of the vaccine on the health of the vaccinated, the construct enabled the identification of a lower propensity of correctness between the interviewed parents when asked about the reduction in the chance of acquiring genital warts and on the efficacy of the vaccine in reducing alterations caused by HPV in the examination screening of the cervix (pap). Health professionals in the McRee et al.38 study gave parents assurances that the HPV vaccine is safe and still claim to influence the parents' decision about the vaccination of their children.

Nunes et al.39 agree that the vaccine is highly effective for the prevention of specific viral serotypes (HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18), and Harper and Demars40 evaluated and tested the efficacy of the vaccine for the prevention of HPV in this first vaccination decade.

Thus, there is evidence in the literature of the benefits of the HPV vaccine. Health professionals need to be more proactive in recommending the HPV vaccine, instructing not only in informed decision-making but emphasizing its importance and the commitment to complete the series of vaccines required by the government, ensuring adequate vaccine coverage41.

The health professionals present a greater proportion of correctness in the related questions on the knowledge of HPV, about it being a sexually transmitted disease and having cervical cancer-related aetiology. Figueroa-Downing10 corroborates a similar proportion of correctness regarding HPV and its sexual transmission.

The relationship between the alterations found in cervical oncology cytology and HPV infection was a knowledge gap among the health professionals interviewed identified by the construct. Health professionals still did not relate smoking to cervical cancer, revealing doubts or issues needing to be clarified in health education training for professionals and that affect adolescent health.

Regarding the knowledge about the HPV vaccine, the interviewees revealed doubts about its efficacy against cervical cancer precursor lesions, the vaccine regimen and its safety. Studies demonstrate the efficacy of the vaccine in reducing low- and high-grade cervical lesions in countries that have adopted the vaccine as a primary form of prevention of cervical cancer for more than 5 years4,39,42.

Health professionals recommend vaccination as a primary prevention of HPV43 and state that they offer the HPV vaccine as an optional immunization for adolescents38. This reinforces the importance of territorial studies and health professionals on the subject. The results demonstrate that the health professionals interviewed know that the vaccine is offered free of charge by the health system and is part of the national immunization programme.

The health professionals oriented regarding the competence to indicate the vaccine and insurance in their concepts regarding efficacy and safety are guiding in this process of implantation of new means of prevention of condyloma acuminata, cervical cancer and among other repercussions caused by HPV, contributing to public health in the construction of preventive actions and strategies19,44.

Health professionals should be up to date with the nationally implemented programme and attentive to the knowledge gaps of parents and adolescents about HPV and its repercussions in order to guide them more effectively. They should also identify the acceptance barriers that exist in the health education regarding the HPV vaccine, demystifyi taboos in the population and contribute towards complete vaccine coverage7,20.

On the other hand, fears about vaccine safety and the information conveyed by some groups have impacted acceptability in some countries32,45,46,47. Because it is a recent vaccine, more follow-up studies are needed in the different countries following the introduction of vaccination. Policies and programmes need to be reviewed and re-evaluated as research results and monitoring data become available.

Thus, in the qualitative approach, the methodological rules of empirical search of the literature are not fixed and totally defined, bringing a limitation to the study in terms of the systematization of the review. The elaboration of the construct through a qualitative review is flexible and particular with evolution throughout the research for a construct based on the interaction and analysis of the researchers13,14.

The strengths of the present study are the novelty of the questionnaire, presenting a more accessible language (since a good part of the target audience is lay), with questions directed to parents, adolescents and specific to health professionals and females, as well as the ability to test the said research instrument, which may serve as a basis for future studies. A possible limitation can be attributed to the small number of participants, making it difficult to establish statistically significant differences between the subgroups.

The construct enables the identification of the knowledge and perception of topics such as HPV, its repercussions on women's health and the acceptability of the vaccine by the target population as well as by the parents and health professionals. Finally, the construct enables the application of the data collection instrumenting diverse populations.

CONCLUSION

The construct/instrument was adequate in assessing the knowledge about HPV, its repercussions and its vaccine among adolescents, parents/guardians and health professionals, as well as assessing the acceptability of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Thus it is an adequate instrument for the collection of data on the thematic knowledge and perception of topics such as HPV, its interaction with the human host, and the HPV vaccine.

REFERENCES

1. Forman D, Martel C, Lacey CJ, Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bruni L, et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012;30( Suppl 5):F12-23. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.055 [ Links ]

2. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, October 2014. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2014;89(43):465-91. [ Links ]

3. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Incidência de câncer no Brasil: estimativa/2016. Brasília: Instituto Nacional do Câncer. [cited 2017 oct 16] Available from: http://www.inca.gov.br/estimativa/2016/estimativa-2016-v11.pdf. [ Links ]

4. Dillner J, Kjaer SK, Wheeler CM, Sigurdsson K, Iversen OE, Hernandez-Avila M, et al. Four year efficacy of prophylactic human papillomavirus quadrivalent vaccine against low grade cervical, vulvar, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and anogenital warts: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c3493. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3493 [ Links ]

5. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância de Doenças Transmissíveis. Coordenação-Geral do Programa Nacional de Imunizações. Informe Técnico da vacina Papiloma vírus humano 6, 11, 16 e 18 (recombinante). Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2015. [ Links ]

6. Kilic A, Seven M, Guvenc G, Akyuz A, Ciftci S. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccine by adolescent girls and their parents in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(9):4267-72. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.9.4267 [ Links ]

7. Phan DP, Pham QT, Strobel M, Tran DS, Tran TL, Buisson Y. Acceptability of vaccination against Human Papillomavirus (HPV) by pediatricians, mothers and young women in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2012;60(6):437-46. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respe.2012.03.010 [ Links ]

8. Kwan TT, Chan KK, Yip AM, Tam KF, Cheung AN, Young PM, et al. Barriers and facilitators to human papillomavirus vaccination among Chinese adolescent girls in Hong Kong: a qualitative-quantitative study. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(3):227-32. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/sti.2007.029363 [ Links ]

9. Kornfeld J, Byrne MM, Vanderpool R, Shin S, Kobetz E. HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability among Hispanic fathers. J Prim Prev. 2013;34(0):59-69. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10935-013-0297-0 [ Links ]

10. Figueroa-Downing D, Baggio M, Baker ML, Chiang EDO, Villa LL, Eluf Neto J, et al. Factors influencing HPV vaccine delivery by healthcare professionals at public health posts in São Paulo, Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;136(1):33-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12004 [ Links ]

11. Osis MJD, Duarte GA, de Sousa MH, Conhecimento e atitude de usuários do SUS sobre o HPV e as vacinas disponíveis no Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2014; 48(1):123-33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005026 [ Links ]

12. Colucci MZO, Alexandre NMC, Milani D. Construção de instrumentos de medida na área da saúde. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2015;20(3):925-36. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015203.04332013 [ Links ]

13. Merriam SB. Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco (USA): Jossey-Bass, 1998; p.179. [ Links ]

14. Yin RK. Estudo de caso: planejamento e métodos. 3ed. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2005; p. 212. [ Links ]

15. World Health Organization (WHO). Young people´s health - a challenge for society. Geneva: WHO, 1986. [ Links ]

16. Giambi C, D'Ancona F, Del Manso M, De Mei B, Giovannelli I, Cattaneo C, et al. Exploring reasons for non-vaccination against human papillomavirus in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:545. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0545-9 [ Links ]

17. Fu CJ, Pan XF, Zhao ZM, Saheb-Kashaf M, Chen F, Wen Y, et al. Knowledge, perceptions and acceptability of HPV vaccination among medical students in Chongqing, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(15):6187-93. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.15.6187 [ Links ]

18. Rosberger Z, Krawczyk A, Stephenson E, Lau S. HPV vaccine education: enhancing knowledge and attitudes of community counselors and educators. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(3):473-77. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0572-z [ Links ]

19. Mazzadi A, Paolino M, Arrossi S. HPV vaccine acceptability and knowledge among gynecologists in Argentina. Salud Publica Mex. 2012;54(5):515-22. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-36342012000500008 [ Links ]

20. Poole DN, Tracy JK, Levitz L, Rochas M, Sangare K, Yekta S, et al. A cross-sectional study to assess hpv knowledge and HPV vaccine acceptability in mali. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56402. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056402 [ Links ]

21. Maia TQ, Soares LO, Valle PASS, Medeiros VMG. Educação para sexualidade de adolescentes: experiência de graduandas. Nexus Rev Extensão IFAM, 2016;2(2):71-8. [ Links ]

22. Domingues CMAS, Alvarenga AT. Identidade e sexualidade no discurso adolescente. Rev Bras Cresc Desenvolv Hum. 1997;7(2):36-63. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.38564 [ Links ]

23. De Groot AS, Tounkara K, Rochas M, Beseme S, Yekta S, Diallo FS, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, practices and willingness to vaccinate in preparation for the introduction of HPV vaccines in Bamako, Mali. PloS One. 2017;12(2):e0171631. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171631 [ Links ]

24. Zouheir Y, Daouam S, Hamdi S, Alaoui A, Fechtali T. Knowledge of human papillomavirus and acceptability to vaccinate in adolescents and young adults of the Moroccan population. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29(3):292-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2015.11.002 [ Links ]

25. World Health Organization (WHO). Monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies. Report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [ Links ]

26. International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer, Appleby P, Beral V, González AB, Colin D, Franceschi S, et al. Carcinoma of the cervix and tobacco smoking: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 13,541 women with carcinoma of the cervix and 23,017 women without carcinoma of the cervix from 23 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2006; 118(6):1481-95. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.21493 [ Links ]

27. Read DS, Joseph MA, Polishchuk V, Suss AL. Attitudes and perceptions of the HPV vaccine in Caribbean and African-American adolescent girls and their parents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23(4):242-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2010.02.002 [ Links ]

28. Wang LDL, Lam WWT, Fielding R. Determinants of human papillomavirus vaccination uptake among adolescent girls: A theory-based longitudinal study among Hong Kong Chinese parents. Prev Med. 2017;102:24-30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.06.021 [ Links ]

29. Reiter PL, Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, McRee AL, Smith JS. Parents' health beliefs and HPV vaccination of their adolescent daughters. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(3):475-80. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.024 [ Links ]

30. Ogilvie GS, Remple VP, Marra F, McNeil SA, Naus M, Pielak KL, Ehlen TG, Dobson SR, Money DM, Patrick DM. Parental intention to have daughters receive the human papillomavirus vaccine. CMAJ. 2007;177(12):1506-12. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.071022 [ Links ]

31. Chan SSC, Ng BHY, Lo WK, Cheung TH, Chung TKH. Adolescent girls' attitudes on human papillomavirus vaccination. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(2):85-90. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2007.12.007 [ Links ]

32. Markowitz LE, Tsu V, Deeks SL, Cubie H, Wang SA, Vicari AS, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine introduction-the first five years. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl.5):139-48. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.039 [ Links ]

33. Chehuen Neto JA, Braga NAC, Campos JD, Rodrigues RR, Guimarães KG, Sena ALS, et al. Atitudes dos pais diante da vacinação de suas filhas contra o HPV na prevenção do câncer de colo do útero. Cad Saúde Coletiva. 2016; 24(2):248-251. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1414-462X201600020275 [ Links ]

34. Madhivanan P, Krupp K, Yashodha MN, Marlow L, Klausner JD, Reingold AL. Attitudes toward HPV vaccination among parents of adolescent girls in Mysore, India. Vaccine. 2009;27(38):5203-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.073 [ Links ]

35. Grandahl M, Tydén T, Westerling R, Nevéus T, Rosenblad A, Hedin E, et al. To Consent or Decline HPV Vaccination: A Pilot Study at the Start of the National School-Based Vaccination Program in Sweden. J Sch Health. 2017;87(1):62-70. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/josh.12470 [ Links ]

36. Albright K, Barnard J, O'Leary ST, Lockhart S, Jimenez-Zambrano A, Stokley S, et al. Noninitiation and Noncompletion of HPV Vaccine Among English-and Spanish-Speaking Parents of Adolescent Girls: A Qualitative Study. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(7):778-84. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.03.013 [ Links ]

37. Cheruvu VK, Bhatta MP, Drinkard LN. Factors associated with parental reasons for "no-intent" to vaccinate female adolescentes with human papillomavirus vaccine: National Immunization Survey Teen-2008-2012. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17:52. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0804-1 [ Links ]

38. McRee AL, Gilkey MB, Dempsey AF. HPV vaccine hesitancy: findings from a statewide survey of health care providers. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(6):541-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.05.003 [ Links ]

39. Nunes CBL, Arruda KM, Pereira TN. Apresentação da eficácia da vacina HPV distribuída pelo sus a partir de 2014 com base nos Estudos Future I, Future II, e Villa et al. Acta Biomed Brasiliensia. 2015;6(1):1-9. [ Links ]

40. Harper DM, DeMars LR. HPV vaccines-A review of the first decade. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(1):196-204. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.04.004 [ Links ]

41. Head KJ, Vanderpool RC, Mills LA. Health care providers' perspectives on low HPV vaccine uptake and adherence in Appalachian Kentucky. Public Health Nurs. 2013;30(4):351-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/phn.12044 [ Links ]

42. Dochez C, Bogers JJ, Verhelst R, Rees H. HPV vaccines to prevent cervical cancer and genital warts: an update. Vaccine. 2014;32(14):1595-1601. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.081 [ Links ]

43. Stormo AR, Moura L, Saraiya M. Cervical cancer-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices of health professionals working in brazil's network of primary care units. Oncologist. 2014;19(4):375-82. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0318 [ Links ]

44. Bezerra IMP, Sorpreso ICE. Conceitos de saúde e movimentos de promoção da saúde em busca da reorientação de práticas. J Hum Growth Dev. 2016,26(1):11-20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.113709 [ Links ]

45. Cunningham M, Davison C, Aronson K. HPV vaccine acceptability in Africa: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2014;69:274-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.035 [ Links ]

46. Hendry M, Lewis R, Clements A, Damery S, Wilkinson C. "HPV? Never heard of it!": a systematic review of girls' and parents' information needs, views and preferences about human papillomavirus vaccination. Vaccine. 2013;31(45):5152-67. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.091 [ Links ]

47. Braz NS, Lorenzi NP, Sorpreso ICE, Aguiar LM, Baracat EC, Soares-Júnior JM. The acceptability of vaginal smear self-collection for screening for cervical cancer: a systematic review. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2017;72(3):183-187. DOI:10.6061/clinics/2017(03)09. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

icesorpreso@usp.br

Manuscript received: October 2017

Manuscript accepted: December 2017

Version of record online: March 2018