Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.23 no.1 São Paulo jan./abr. 2021

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPC1913554

10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPC1913554 COVID-19

Covid-19 pandemic implications for education and reflections for school psychology

Implicações da covid-19 para a educação e reflexões para a psicologia escolar

Implicaciones de la covid-19 para la educación y reflexiones para psicología escolar

Wanderlei A. de OliveiraI ; André Luiz M. AndradeI

; André Luiz M. AndradeI ; Vera Lucia T. de SouzaI

; Vera Lucia T. de SouzaI ; Denise De MicheliII

; Denise De MicheliII ; Luciana Mara M. FonsecaIII

; Luciana Mara M. FonsecaIII ; Luciane S. de AndradeIII

; Luciane S. de AndradeIII ; Marta Angélica I. SilvaIII

; Marta Angélica I. SilvaIII ; Manoel Antônio dos SantosIII

; Manoel Antônio dos SantosIII

IPontifical Catholic University of Campinas (PUC-Campinas), Campinas, SP, Brazil

IIFederal University of São Paulo (Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil

IIIUniversity of São Paulo (USP), Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic required non-pharmacological control measures, including schools shutting down and the implementation of remote education. This study aimed to review students' and education professionals' experiences during the pandemic and reflect on the school and educational psychology. It is a scoping review covering six databases, and 15 articles composed the corpus. There was a concern with higher education training and emerging demands for teachers and students who were required to adhere to different teaching-learning tools. Teachers' and students' evaluations are positive, considering that remote activities ensure flexibility and creativity. On the other hand, there is substantial concern about exclusion due to non-access or limited access to the internet or computers. The impact of this remote education experience will be evaluated in the future, but it is already possible to point out implications for psychology in the face of the "new normal."

Keywords: COVID-19; pandemic; evidence-based education; school psychology; review.

RESUMO

A pandemia do COVID-19 exigiu medidas não farmacológicas para seu controle, como o fechamento das escolas e a implantação do ensino remoto. Este estudo objetivou analisar a experiência de estudantes e profissionais da educação durante a pandemia e apresentar reflexões para o campo da psicologia escolar e educacional. Trata-se de uma scoping review que consultou seis bases de dados e o corpus foi composto por 15 artigos. Verificou-se preocupação com formação no ensino superior, bem como demandas emergentes para professores e alunos que precisaram aderir a diferentes ferramentas de ensino-aprendizagem. A avaliação de professores e alunos é positiva, considerando que as atividades remotas garantem maior flexibilidade e criatividade, porém há forte preocupação com a exclusão pelo não acesso ou acesso limitado à internet ou computadores. O impacto dessa vivência remota da educação será avaliado futuramente, mas já é possível sinalizar implicações para o campo da psicologia diante do "novo normal".

Palavras-chave: Covid-19; pandemia; educação baseada em evidências; psicologia escolar; revisão.

RESUMEN

La COVID-19 requirió medidas no farmacológicas para controlarla, incluido el cierre de escuelas y la implementación de educación a distancia. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo analizar la experiencia de estudiantes y profesionales de la educación durante la pandemia y presentar reflexiones para la psicología escolar y educativa. Es una scoping review que consultó seis bases de datos y el corpus estuvo compuesto por 15 artículos. Había una preocupación por la formación en educación superior, así como por las demandas emergentes de profesores y estudiantes. La evaluación de docentes y estudiantes es positiva, considerando que las actividades a distancia garantizan flexibilidad y creatividad, sin embargo, existe una preocupación por la exclusión debido a la falta de acceso o al acceso limitado a internet o computadoras. El impacto de esta experiencia será evaluado en el futuro, pero ya es posible señalar implicaciones para la Psicología de cara a la "nueva normalidad".

Palabras clave: COVID-19; pandemia; educación basada en evidencia; psicología escolar; revisión.

1. Introduction

Formal education and schools are strategic resources for citizens' education from the perspective of human development (Grech, 2020). With the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), educational institutions were affected by contagion control measures. Different instances and academic units recommended the closure of schools and began implementing remote activities worldwide (Oliveira, Gomes, & Barcellos, 2020). However, it is known that the educational system is complex and, in the face of the sudden onset of an unprecedented global health emergency like the current pandemic, no structured plan was in place to cope with continuing educational practices or to face the crisis (Lopes & McKay, 2020). The experience of adaptability of the teaching work and the students' study routine has indicated that new paths will be followed in terms of the teaching-learning process (Arnove, 2020; Stambough et al., 2020).

Although the issue is recent, it is already evident that there are gaps in scientific production on how countries and their respective governments have approached COVID-19 and its substantial impacts on people's education at different levels (Tufan, 2020). This is due to the current nature of the issue and the difficulty in structuring alternative teaching or learning plans concerning the face-to-face condition model, which promotes people's gathering in closed spaces, increasing the risk of contagion. Furthermore, researchers focus on epidemiological and clinical issues to learn how the new coronavirus behaves and its evolution dynamics (Ferguson et al., 2020). Thus, there is a need to invest in studies that allow taking into account other relevant dimensions of the problem, such as the psychosocial impacts of barriers and immediate challenges resulting from the adoption of restrictive circulation and social contact measures. Among them, the abrupt closure of schools stands out, resulting in the forced implementation of remote activities, often disconnected from the curricula and constituting barriers in the interaction between the different protagonists that make up the school universe. This is important because it is understood that, in a post-pandemic scenario, new strategies will be required to operationalize education in teaching institutions.

It is assumed that the new coronavirus' unusual scenario contains lessons learned by educational institutions, teachers, students, families, and school and public managers, besides the community. In addition, with the migration of a significant portion of teaching-learning activities to the online environment, one of the consequences of this new era concerns the need to accelerate the discussion on democratizing access to technologies and their consequent use for educational purposes. It is also essential to consider education professionals' training to qualify them to use these tools and develop teaching strategies accordingly. This demand requires reconsidering social inequalities in emerging countries, such as Brazil, which affect most of the population's access to quality education. Furthermore, teachers' training still encounters structural barriers that challenge teachers' qualifications. Thus, the curricula and the teacher training programs must also be reconsidered, based on the "new normal" arising from the coexistence with the pandemic of COVID-19 (Carr, 2020), this being the second lesson to be learned. It is also assumed that it is imperative that educational institutions, at different levels, create contingency plans to accommodate the likely lasting effects of the pandemic and invest in safety protocols for the reopening of schools and progressive return to teaching-learning activities, which should be done in partnership with other instances of society, such as health.

Given this scenario, this study aimed to analyze the experience of children, youth, and education professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic through a scoping review. Based on the scientific production survey in this scenario, emerging issues and the main challenges in school and educational psychology have been addressed.

2. Method

2.1 Study type

This is a systematic literature review of the scoping type (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015). This type of review aims to document the recent literature aspects still little explored by research, favoring the understanding of specific topics before focusing on more particular issues (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). In the COVID-19 pandemic case, empirical data are still exploratory, heterogeneous, and focused on understanding the problem, which precludes systematic reviews that include other variables affected by the pandemic situation. Thus, to achieve a first look at how education has been affected by the pandemic, to examine the extent of the scientific literature on the subject, and determine its diversity, the scoping review is a methodological tool that meets this demand.

2. 2 Methodological procedures

This study complied with the recommendations proposed for the drawing of a scoping review. In this sense, five steps were followed: delimitation of the investigation question; identification of relevant studies; selection of studies; analysis of the data reviewed; grouping, summary, and dissemination of results (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). The first author searched the databases, and his findings were reviewed by another investigator who independently validated the decisions made. Both evaluators have expertise in the area. The investigation was conducted in June and July 2020.

2. 3 Guiding question

The investigation question was built from the acronym PCC (P = population; C = concept; C = context; The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015): What is the impact or effect of the COVID-19 pandemic for the players involved at the different levels of education?

2. 4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies focusing on different education levels were covered to include all school populations, valuing the impacts and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on education. Inclusion criteria were: empirical articles, reviews, theoretical-reflective studies published in Portuguese, English, and/or Spanish. The survey team excluded editorial texts, letters, comments, chapters, books, and health education studies.

2. 5 Selection of data sources

The Web of Science, PsycINFO, ERIC (Education Resources Information Center), Scopus, SciELO, and the PUBCOVID19 platform that collects articles on COVID-19 indexed in PubMed and EMBASE were selected for consultation. The selection of these bases is justified due to the subject's multidisciplinary scope investigated while safeguarding the specificity of some areas, such as Education and Psychology.

2. 6 Data collection, organization, and analysis

For preliminary recognition of descriptors or keywords related to COVID-19, non-systematic research was carried out at the sources PUBCOVID19 and Web of Science. From this survey, it was found that the words most used for indexing studies within the framework of the current pandemic were: COVID-2019, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2. To define the population of interest, the following terms were included: Education and school. For the combination of descriptors in the search process, the Boolean terms AND and OR were considered. In SciELO, the terms were also used in Portuguese. We ought to observe that, in a scoping review, it is essential to adopt broad and specific definitions so that no relevant article is lost in the screening process (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005).

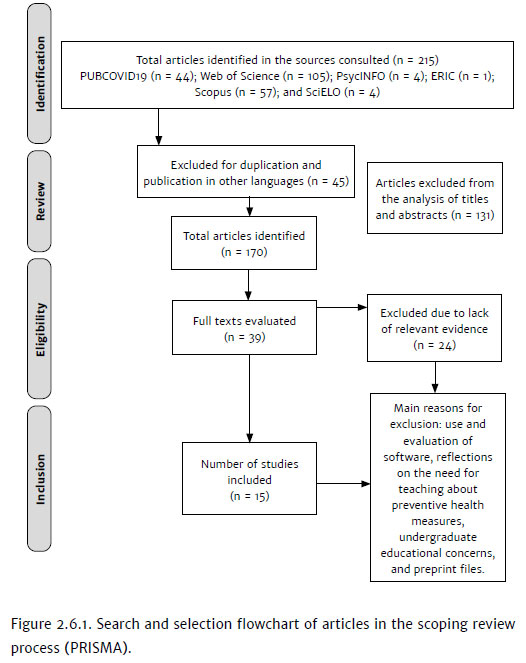

PRISMA guidelines were followed to put in systematic order the inclusion process of studies (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, 2009). The flowchart for searching and selecting articles is shown in Figure 2.6.1.

The articles excluded in the first screening (reading of titles and abstracts) covered subjects such as the use of technology and health education to monitor COVID-19, how communication about the disease and the new coronavirus reached the general population, and the role of social networks, such as Instagram and Youtube, in the health education processes. To extract data from articles included in the review, a spreadsheet was used to fill in the following information: authors, journal, year of publication, country of origin, the purpose of the study, population/sample, methodological design, and main results.

The results reviewed will be presented in a table and in a narrative format covering aspects that answer the question that stands behind the scoping review. This review step aims to describe the main subjects already investigated on the topic of interest and point out significant gaps explored in other investigations (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). In interpreting the results, the expressive-creative technique "whirlwind of ideas" was also used; this appellation is a metaphor inspired by a teaching-learning pedagogical proposal (Ontoria, Gómez, & Luque, 2014).

3. Results

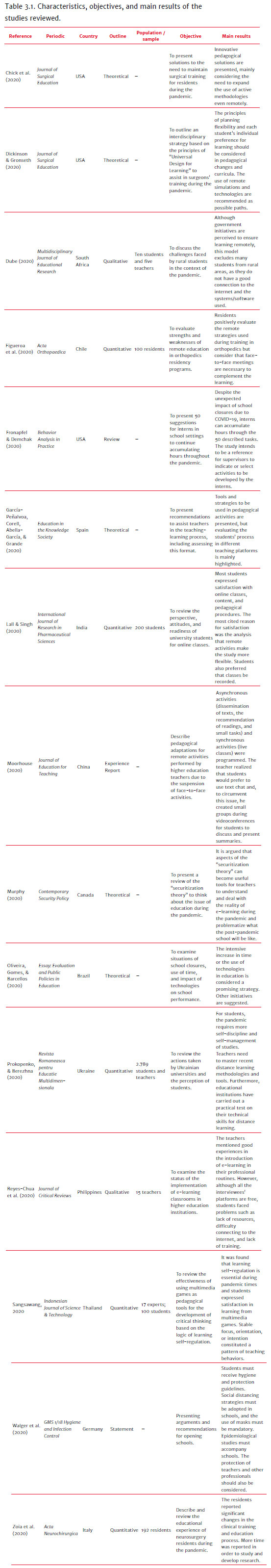

After the evaluation and selection process, 15 scientific articles were included in this scoping review, 13 of which were published in English, one in Spanish, and one in Portuguese. The majority (n = 8) of the papers contained theoretical reflections or literature reviews. However, it is observed that the primary research already carried out in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic brings together significant sample groups. The bibliometric data of the studies and their main results are shown in Table 3.1.

From the data, it can be seen that the impact of the educational institutions' closure and the new demands facing teachers and students has not yet been significantly reviewed in Brazil. In contrast, even though the pandemic situation is current, scientific production already includes three reflections on the issue in the United States of America (USA). There is also an evident concern with higher education courses' functioning, especially concerning the practical part of medical training. In this sense, the data that is focused more on the higher education population, in addition to undergraduate students, also included students at different medical residency stages.

The reviewed studies' objectives clearly show that the first trend identified is searching for suggestions to teachers. How to implement teaching strategies capable of stimulating and motivating students? Remote activities require specific technical skills and a good repertoire for communication and interaction between teachers and students. It is noted that these players are concerned with developing their new roles in schools or universities, but they also have to deal with the demands of daily life and the direct consequences of the pandemic in their lives.

The reviewed studies also provide information about teachers' and students' perceptions about the adopted teaching strategies after the schools shut down. The use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) was already a reality for many individuals; however, their intensification and exclusive use initially generated feelings of helplessness and frustration, especially in higher education, as classroom activities are perceived as essential for the technical training in the case of health courses (Murphy, 2020; Oliveira et al., 2020). Teachers and students also found it challenging to adapt to the online reality and required training to use different tools (Dube, 2020; Figueroa et al., 2020).

However, as a general assessment, students and teachers feel satisfied with remote activities and realize that such activities are relevant for the times of exception currently experienced (Reyes-Chua et al., 2020; Sangsawang, 2020; Zoia et al., 2020). These data have been verified in empirical studies. Online activities, particularly those asynchronous, are considered promising, as they can offer greater flexibility for students (Lall & Singh, 2020; Chick et al., 2020). The results indicate good acceptance and adherence by both teachers and students to the remote activities that replaced classroom activities. No difficulties were reported in this regard, but a study revealed that resident medical students consider face-to-face meetings necessary to complement learning (Figueroa et al., 2020). However, there are concerns about differentiated access to the internet or appropriate equipment, especially for students, to continue their distance learning (Dube, 2020; Chick et al., 2020).

From a practical standpoint, the studies' suggestions or recommendations focus on the importance of ensuring that significant learning is preserved through the mediation of technology (Chick et al., 2020). To this end, teachers can propose pedagogical activities of a different nature, using games and resources from teaching platforms, such as quizzes, online forums, and chats (Fronapfel & Demchak, 2020; García-Peñalvoa, Corell, Abella-García, & Grande, 2020). These activities require constant support from the teacher, who must monitor the students' learning and, at the same time, the joint development (Dickinson & Gronseth, 2020). This aspect reveals that, even in the remote model, there is no significant reduction in teachers' efforts to guarantee an effective teaching-learning process (Prokopenko & Berezhna, 2020).

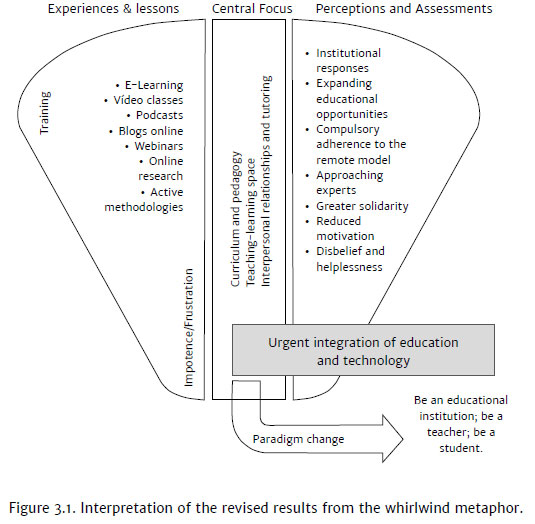

The reviewed data were also assessed altogether and using the expressive-creative technique "whirlwind of ideas": experiences, meanings, impressions, and feelings were recorded in a graphic representation in which there is a specific condition ("being in the loop") and elements that indicate a lack of control over what is happening ("like a catastrophe of nature"). In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the initial results are, in general, described with the terms: suffering, helplessness, sadness, and feelings of desolation that can encompass other dimensions of life, such as education. In this sense, the reviewed data showed two levels of complexity about the pandemic's implications for education and pedagogical practices. At the first level, the impact of the pandemic situation materialized, which caused the sudden suspension of classroom teaching and students' socialization, the adoption of remote activities, and the emergency demand for training of students and teachers on online platforms causing negative feelings (impotence and frustration). On the other level, the perceptions and evaluations arising from this rupture movement in daily life emerged. These interpretations are summarized schematically in Figure 3.2.

It should be observed that the instructional programs were dramatically affected by the pandemic, which changed the teaching model, switching the classroom to remote activities or intensifying this model. This decision-making forced teachers to review their disciplines' planning, considering that skills and content should be developed even though the remote learning was implemented. It was also observed that whatever the institutional conditions offered to teachers and students, extra support and training measures are required in order to use technological tools and different platforms. It is also necessary to think about the quality of internet access and the availability of computers or other electronic devices for all students.

4. Discussion

This scoping review explored the recent literature on the COVID-19 pandemic impact on education. This study allows us to understand better how teachers and students experienced the institutional responses and guidance of the forced adherence to the remote model. This aspect can be found in empirical studies already published in scientific journals. There were also recommendations and suggestions on making remote activities more meaningful, reducing damage to the teaching-learning process. The interpretative synthesis of the findings revealed a potential paradigm shift for the education area, requiring new ways of being an educational institution, being a teacher, and being a student. The data reviewed can guide future research and have implications for the field of school and educational psychology.

Even with a broad cultural diversity, since the studies originate from 13 countries, no differences between pedagogical concerns or how to deal with pandemic times were recorded. It is also important to note that most studies focused on higher education training, although the greatest number of those affected is in primary education. Moreover, in addition to the articles included in this review, many comments or editorials manifested concerns about universities' reality in connection to the pandemic. For example, the scientific community is encouraged to think about medical training (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020), as well as to enhance the need to include correct hand hygiene in remote undergraduate nursing courses (Ng & Or, 2020). In psychology, the concern was on the challenges of preparing future professionals for mental health care and the use of ICTs in the training process (Bell et al., 2020).

COVID-19 pandemic is another major challenge for contemporary education. It was observed that teachers were already incorporating the technological culture in activities in the classroom or outside classes (Chick et al., 2020; Saveleva, 2019). This drive aims to meet the demands of an increasingly computerized and connected world, but that alone does not promote learning (Oliveira et al., 2020). In other words, teachers were already required to plan and develop pedagogical activities that included the teaching content but were also significant and capable of stimulating student leadership (Saveleva, 2019). With the closure of schools and the discontinuation of face-to-face activities, this process was accelerated, and the scenario became even more conducive to changes, and, as noted, teachers and students had to adapt quickly.

However, adaptive adjustment to the "new normal" was not facilitated by discussions that preceded the pandemic moment in preparation for potential events of this magnitude. Demands for training and negative feelings experienced on account of the remote modality requirements were manifested, especially in teachers' cases. In Brazil, research indicates that instrumental rationality remains the dominant trait in teacher education, which values the reproduction of the content, ignoring, for example, technologies as content and strategy for teaching (Echalar & Peixoto, 2016). This has been a priority topic, if not in the field of initial training, in the context of continuing education. However, the massive use of these technologies does not materialize for several reasons, among which the lack of appropriate equipment and even the updating of teachers concerning new tools multiply very quickly.

On the other hand, given Brazil's small representativeness in this review, it is clear that it is necessary to understand how Brazilian teachers and students are experiencing this pandemic situation, the closure of schools, and the suspension of classroom activities. Through daily news disseminated in different outlets or from the experience of this study's investigators in educational institutions, it is known that problems are immense and challenging. In the state school system in the State of São Paulo, for example, with around three and a half million students, 250,000 teachers, and 5,000 schools, it is estimated that 50% of the students, on average, do not access the classes or activities offered by the Department of Education and by the schools due to lack of adequate equipment, schedule conflicts or lack of interest (Apeoesp, 2020). Many of those who access the facilities offered are about to give up because they cannot keep up with classes. A recent survey interviewed 1,018 parents or guardians of 1,518 public schools' students from different regions of the country and showed that 31% of parents fear that their children will drop out of school; out of this total, 71% say their children are unmotivated to study (Datafolha, 2020).

The scientific concern should also be borne in mind when investigating how the students can access the necessary resources to remain in the schooling process during the pandemic. These resources refer to a quality internet connection and appropriate electronic equipment. The matter is sensitive to most Brazilian students' reality, who do not have computers available or even adequate access to the internet. In higher education, it is worth noting that socioeconomic conditions have already been identified as one of the main factors for student dropout (Noro & Moya, 2019).

In Brazil, in the case of primary public education, in addition to the issues already mentioned, people talk of a "blackout" in learning because even those students who persist in remote activities, despite lacking adequate equipment, are at serious risks of failing and being unsuccessful in the National High School Test (ENEM), which is used today for screening college entrance. In other words, the problems of primary public education are now piling up, and new questions have come at the core of specialists, researchers, and educators' concerns: they include questions such as: how to modernize schools with the necessary equipment for remote education? How to provide conditions for all students to have access to the ICTs? How to transform pedagogical practices congruent with the possibilities and limits of remote education; are they presented as exciting and engaging? How to qualify teachers to master new knowledge and strategies for this form of teaching that appears to be becoming perennial? How to overcome the chronic conditions of inequality regarding housing when it is known that the student shares two rooms at home with many people and cannot concentrate on classes? Finally, many issues must be investigated to offer contributions to overcome these challenges.

From the School and Educational Psychology perspective, it is important to highlight the role of social relations in the face-to-face interaction model in the subjects (Souza et al., 2018). The social environment is a source of development, which is to say that it is from it that people's behavior, thoughts, and relationships derive. In this sense, educational institutions play a fundamental role: it is there that equal-different people meet, mismatch, appropriate, and reject values and norms, exercising respect, acceptance, and welcoming. Divergent and similar ideas and thoughts are also expressed; that is, it is a civilizing spot that helps build up identity. In turn, when appropriated by children and young people, the formal training at school promotes the development of higher psychological functions, enabling new relationships between more complex functions and thoughts of a more in-depth and expanded nature, which allows for the understanding of the world more consciously. In other words, it is the school's role to promote the development of the subject in its entirety. How to ensure that these teaching dimensions are preserved and result in development in times of remote education? This is one of the significant challenges of Educational School Psychology today.

In recent years, Educational School Psychology has advanced in proposing practices aimed at the collectivity in schools, with a view at increasing the collaborative spirit to enhance the relationships between individuals, welcome and give significance to emotions and promote the development of the agents who operate in school. In this connection, school and educational psychology have developed operations that surpass a clinical and diagnostic role in schools. They aim at addressing the school complaints that involve only the student. The action target was defined as the relationship scope and fostering the individuals' development (Souza et al., 2018).

In times of pandemic, psychologists must help teachers and managers understand the events' complexity. The way they impact the production of subjective processes affects the students' teaching and learning performance. It is also necessary to guide schools to open space for teachers to express their difficulties and offer creative ways of action that can attract students and facilitate teaching. With the change in schools' functioning, psychologists can also help institutions recognize the social challenges that students may face to organize their study routines. This positioning allows us to assess the importance of the psychosocial dimension of action in extreme situations of intense social shock and commotion, which require the forced integration between education and technology. However, it is essential to point out that, for the school's psychologist too, distance action is a challenge to be faced, mainly because the insertion of the psychologist has occurred in the physical space of the school and, with the school shut down, psychologists are momentary without a "place" where to perform. It is necessary to find ways to access managers, teachers, and students remotely, which has not been easy since everyone is overloaded with classes, meetings, and planning.

It is also necessary to point out the greatest challenge to the psychologist's performance at school: the psychologist is not a professional who belongs to the school's pedagogical or administrative body, since the figure of the school psychologist does not exist in most public education institutions, and this has hindered the penetration and limited the capillarity of this professional's actions. It also favors the maintenance of the psychologist's social representation as a professional who works with isolated individuals and intervenes only in extreme cases involving emotions. This picture keeps off teachers, insofar as accepting the psychologist's help is equivalent to admitting malaise, disturbance, or lack of knowledge, especially in a pandemic, when teachers are under extreme pressure to plan subjects, forward materials to students, get students to do and return their homework, review assignments and answer questions of many students by message.

The studies reviewed also indicate that student engagement in remote activities can and should be explored. In this connection, there is already a current discussion on the gamification of educational processes with the generations that were born connected or that make constant use of technologies (Silva, Sales, & Castro, 2019). The use of digital games also stimulates cognitive functions, such as greater psycho-emotional engagement with activities, activation of the neuropsychological reward system, and a sense of well-being caused by fun (Rivero, Querino, & Starling-Alves, 2012). Games are considered low-cost tools; some are available for free online and can be used in different contexts. Nevertheless, teachers are not always prepared to share this type of instrument, and psychologists can assist in the adherence and implementation of this nature (Ramos, Bianchi, Rebello, & Martins, 2019). However, great care must be taken not to transfer to the ICTs the task of promoting education, as we already know that what keeps young people in digital games is the immediate reward that the playful character of the game offers and, depending on this strategy's use, it will not be possible to promote the development of the subjects.

5. Final considerations

This scoping review identified the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for education and school practices. Thus, it was realized that more research is still necessary to understand how education and school responded to the pandemic situation and how this situation will impact educational models. The reviewed studies have focused more on pedagogical issues arising from technology and its effects on the teaching-learning process. There is a consensus that remote activities produce satisfactory results, with a perception that they help reducing damage to the teaching-learning process in the face of the pandemic situation. In general, we found that Psychology could help in the process of creative adaptation of teachers to the "new normal" to which they were forced, and that requires training or even specific suggestions on how to perform in the remote model.

Considering this review's methodological rigor, the data presented must be interpreted in the framework of their three main limitations. Firstly, the current situation of the pandemic still in progress during the performance of the scoping review. The interruption of teaching and research activities may have impacted the primary studies' low frequency, which addresses the epidemiological moment and education interface. Second, the number of reflective or review studies included did not allow a review of the scientific evidence quality. Third, the authors did not examine the interaction among the categories recorded in their analysis. The third limitation is that the first author did not categorize the effects of the pandemic on student though this was not an objective of the review, this aspect prevents conclusions about the effectiveness of remote activities for self-regulation or more discipline. Future research should focus on replicating and expanding this review investigation. As previously indicated, post-pandemic education and schools should be rethought, and the effects of institutions and people's adaptive functioning under these circumstances should be measured. Research on the experience of Brazilian teachers and students will also be welcome.

References

Apeoesp (2020). Levantamento da APEOESP EaD. Retrieved from http://www.apeoesp.org.br/ [ Links ]

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8,19-32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616 [ Links ]

Arnove, R. F. (2020). Imagining what education can be post-COVID-19. Prospects, 2,1-4. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09474-1 [ Links ]

Bell, D. J., Self, M. M., Davis, C., III, Conway, F., Washburn, J. J., & Crepeau-Hobson, F. (2020). Health service psychology education and training in the time of COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. American Psychologist. Advance online publication, 1-14. doi:10.1037/amp0000673 [ Links ]

Carr, E. (2020). New normal terminology. CJON, 24(3),223. doi:10.1188/20.CJON.223 [ Links ]

Chick, R. C., Clifton, G. T., Peace, K. M., Propper, B. W., Hale, D. F., Alseidi, A. A., & Vreeland, T. J. (2020). Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Surgical Education, 77(4),729-732. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018 [ Links ]

Datafolha (2020). Educação não presencial na perspectiva dos estudantes e suas famílias. São Paulo: Fundação Lemann. Retrieved from https://fundacaolemann.org.br/materiais/educacao-nao-presencial-na-perspectiva-dos-alunos-e-familias [ Links ]

Dias, A. C. G., Patias, N. D., & Abaid, J. L. W. (2014). Psicologia Escolar e possibilidades na atuação do psicólogo: algumas reflexões. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 18(1),105-111. doi:10.1590/S1413-85572014000100011 [ Links ]

Dickinson, K. J., & Gronseth, S. L. (2020). Application of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles to surgical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Surgical Education, 77(5),1008-1012. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.005 [ Links ]

Dube, B. (2020). Rural online learning in the context of COVID 19 in South Africa: Evoking an inclusive education approach. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 10(2),135-157. doi:10.17583/remie.2020.5607 [ Links ]

Echalar, A. D. L. F., & Peixoto, J. (2016). Inclusão excludente e utopia digital: A formação docente no Programa Um Computador por Aluno. Educar em Revista, (61), 205-222. doi:10.1590/0104-4060.46088 [ Links ]

Ferguson, N. M., Laydon, D., Nedjati-Gilani, G., Imai, N., Ainslie, K., Baguelin, M. ... Ghani, A. C. (2020). Report 9: impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce Covid19 mortality and healthcare demand. London: Imperial College Covid-19 Response Team. [ Links ]

Ferrel, M. N., & Ryan, J. J. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education. Cureus, 12(3),e7492. doi:10.7759/cureus.7492 [ Links ]

Figueroa, F., Figueroa, D., Calvo-Mena, R., Narvaez, F., Medina, N., & Prieto, J. (2020). Orthopedic surgery residents' perception of online education in their programs during the COVID-19 pandemic: Should it be maintained after the crisis? Acta Orthopaedica, 1-4. doi:10.1080/17453674.2020.1776461 [ Links ]

Fronapfel, B. H., & Demchak, M. (2020). School's out for COVID-19: 50 ways BCBA trainees in special education settings can accrue independent fieldwork experience hours during the pandemic. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13,312-320. doi:10.1007/s40617-020-00434-x [ Links ]

García-Peñalvoa, F. J., Corellb, A., Abella-García, V., & Granded, M. (2020). La evaluación online en la educación superior en tiempos de la COVID-19. Education in the Knowledge Society, 21,e12. doi:10.14201/eks.23013 [ Links ]

Grech, V. (2020). Unknown unknowns: COVID-19 and potential global mortality. Early human development, 144,105026. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105026 [ Links ]

Lall, S., & Singh, N. (2020). CoVid-19: Unmasking the new face of education. International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences, 11(1),48-53. doi:10.26452/ijrps.v11iSPL1.2122 [ Links ]

Lopes, H., & McKay, V. (2020). Adult learning and education as a tool to contain pandemics: The COVID-19 experience. International review of education. Internationale Zeitschrift fur Erziehungswissenschaft. Revue internationale de pedagogie, 1-28. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s11159-020-09843-0 [ Links ]

Martinez, A. M. (2009). Psicologia Escolar e Educacional: Compromissos com a educação brasileira. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 131),169-177. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-85572009000100020&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7),e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [ Links ]

Moorhouse, B. L. (2020). Adaptations to a face-to-face initial teacher education course 'forced' online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4),609-611. doi:10.1080/02607476.2020.1755205 [ Links ]

Murphy, M. P. A. (2020). COVID-19 and emergency eLearning: Consequences of the securitization of higher education for post-pandemic pedagogy. Contemporary Security Policy, 41(3),492-505. doi:10.1080/13523260.2020.1761749 [ Links ]

Ng, Y.-M., & Or, P. L. P. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) prevention: Virtual classroom education for hand hygiene. Nurse education in practice, 45,102782. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102782 [ Links ]

Noro, L. R. A., & Moya, J. L. M. (2019). Condições sociais, escolarização e hábitos de estudo no desempenho acadêmico de concluintes da área da saúde. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde, 17(2),e0021042. doi:10.1590/1981-7746-sol00210 [ Links ]

Oliveira, J. B. A., Gomes, M., & Barcellos, T. (2020). A Covid-19 e a volta às aulas: Ouvindo as evidências. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 28(108),555-578. doi:10.1590/s0104-40362020002802885 [ Links ]

Ontoria, A., Gómez, J. P. R., & Luque, A. (2014). Aprendizaje centrado en el alumno (3 ed.). Madrid: Narcea. [ Links ]

Prokopenko, I., & Berezhna, S. (2020). Higher education institutions in Ukraine during the coronavirus, or COVID-19, outbreak: New challenges vs new opportunities. Revista Romaneasca pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(1Sup2),130-135. doi:10.18662/rrem/12.1sup1/256 [ Links ]

Ramos, D. K., Bianchi, M. L., Rebello, E. R., & Martins, M. E. O. (2019). Intervenções com jogos em contexto educacional: contribuições às funções executivas. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 21(2),316-335. doi:10.5935/1980-6906/psicologia.v21n2p316-335 [ Links ]

Reyes-Chua, E., Sibbaluca, B. G., Miranda, R. D., Palmario, G. B., Moreno, R. P., & Solon, J. P. T. (2020). The status of the implementation of the e-learning classroom in selected higher education institutions in region IV: A amidst the covid-19 crisis. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(11),253-258. doi:10.31838/jcr.07.11.41 [ Links ]

Rivero, T. S., Querino, E. H., & Starling-Alves, I. (2012). Videogame: Seu impacto na atenção, percepção e funções executivas. Neuropsicologia Latinoamericana, 1(1),38-52. doi:10.5579/rnl.2012.109 [ Links ]

Sangsawang, T. (2020). An instructional design for online learning in vocational education according to a self-regulated learning framework for problem solving during the COVID-19 crisis. Indonesian Journal of Science & Technology, 5(2),283-298. doi:10.17509/ijost.v5i2.24702 [ Links ]

Saveleva, N. N. (2019). A model of personal-oriented training of bachelors of technical profile for high-tech industries. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 27(102),69-87. doi:10.1590/s0104-40362018002601734 [ Links ]

Silva, J. B., Sales, G. L., & Castro, J. B. (2019). Gamificação como estratégia de aprendizagem ativa no ensino de Física. Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física, 41(4),e20180309. doi:10.1590/1806-9126-rbef-2018-0309 [ Links ]

Souza, V. L. T., Aquino, F. S. B., Guzzo, R. S. L., Marinho-Araujo, C. M. (2018). Psicologia Escolar Crítica: atuações em escolas públicas. Campinas: Editora Alínea. [ Links ]

Stambough, J. B., Curtin, B. M., Gililland, J. M., Guild, G. N., Kain, M. S., Karas, V. ... Moskal, J. T. (2020). The past, present, and future of orthopedic education: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 35(7S),S60-S64. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.032 [ Links ]

The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2015). The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Adelaide: JBI. [ Links ]

Tufan, Z. K. (2020). COVID-19 diaries of higher education during the shocking pandemic. Gazi Medical Journal, 31(2A),227-233. doi:10.12996/gmj.2020.61 [ Links ]

Walger, P., Heininger, U., Knuf, M., Exner, M., Popp, W., Fischbach, T., ... Simon, A. (2020). Children and adolescents in the CoVid-19 pandemic: Schools and daycare centers are to be opened again without restrictions. The protection of teachers, educators, carers and parents and the general hygiene rules do not conflict with this. GMS Hygiene and Infection Control, 15,e11. doi:10.3205/dgkh000346 [ Links ]

Zoia, C., Raffa, G., Somma, T., Pepa, G. M. D., La Rocca, G., Zoli, M. ... Fontanella, M. M. (2020). COVID-19 and neurosurgical training and education: An Italian perspective. Acta Neurochirurgica, 162,1789-1794. doi:10.1007/s00701-020-04460-0 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Wanderlei Abadio de Oliveira

Av. John Boyd Dunlop, s/n., 13060-904, Jd. Ipaussurama

Campinas, SP, Brazil. CEP: 13060-904

E-mail: wanderleio@hotmail.com

Submission: 17/08/2020

Acceptance: 30/10/2020

Authors' notes:

Wanderlei A. de Oliveira, Post Graduate Program in Psychology (PGPP), Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas (PUC-Campinas); André Luiz M. Andrade, Post Graduate Program in Psychology (PGPP), Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas (PUC-Campinas); Vera Lucia T. de Souza, Post Graduate Program in Psychology (PGPP), Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas (PUC-Campinas); Denise De Micheli, Post Graduate Program in Psychobiology (PGPP), Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP); Luciana Mara M. Fonseca, Post Graduate Program in Public Health Nursing (PGPPHN), University of São Paulo (USP); Luciane Sá de Andrade, Post Graduate Program in Psychiatric Nursing (PGPPN), University of São Paulo (USP); Marta Angélica I. Silva, Post Graduate Program in Public Health Nursing (PGPPHN), University of São Paulo (USP); Manoel Antônio dos Santos, Post Graduate Program in Psychology (PGPP), University of São Paulo (USP).

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI