Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Temas em Psicologia

versão impressa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.27 no.2 Ribeirão Preto abr./jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2019.2-01

ARTICLE

Gender and adoption in the brazilian context: an integrative review of the scientific literature

Gênero e adoção no contexto brasileiro: revisão integrativa da literatura científica

Género y adopción em el contexto brasileño: revisión integrada de la literatura científica

Juliana Machado RuizI; Camila Aparecida Peres BorgesII; Martha Franco Diniz HuebIII; Rafael De TilioIV; Fabio Scorsolini-CominV

IOrcid.org/0000-0002-0895-5253. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, Uberaba, MG, Brasil

IIOrcid.org/0000-0001-7419-8919. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, Uberaba, MG, Brasil

IIIOrcid.org/0000-0001-7145-0349. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, Uberaba, MG, Brasil

IVOrcid.org/0000-0002-4240-9707. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, Uberaba, MG, Brasil

VOrcid.org/0000-0001-6281-3371. Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brasil

ABSTRACT

The present study aimed to understand how the gender category emerges in studies about adoption in the Brazilian context. The guiding question was: How do researches in the context of adoption, regarding children, parents and professionals, address gender issues? An integrative literature review was conducted on the databases LILACS, SciELO and PePISC with the descriptors adoption, gender and parentality, published between 2007 and 2017. Seventeen articles had been recovered and three categories were constituted: (a) Exercise of maternity in the context of adoption; (b) (In)visibility of paternity in the discussion about adoptive parenting; (c) Homoparentality: meanings of reproductive technology and adoption. The studies brought to light reflections about adoptive parenting and adoptive homoparentality, as well as highlighting the way these couples exercise their parental roles. It is concluded that understanding how parental roles are exercised in these different realities makes it possible to understand different family arrangements, opening more space for families by adoption. It is recommended to expand the gender discussions in order to provide questions and tensions for this scenario, dialoguing with different developmental and clinical perspectives.

Keywords: Adoption, gender, gender identity, homoparentality.

RESUMO

O presente estudo teve por objetivo compreender como a categoria gênero emerge nos estudos sobre adoção no contexto brasileiro. A pergunta norteadora foi: de que forma as pesquisas realizadas no contexto da adoção, que se referem às crianças, pais e profissionais, abordam as questões de gênero? Realizou-se uma revisão integrativa da literatura nas bases de dados LILACS, SciELO e PePISC, com os descritores adoção, gênero e parentalidade, publicados no período entre 2007 e 2017. Foram selecionados 17 artigos, a partir dos quais constituíram-se três categorias de análise: (a) Exercício da maternidade no contexto da adoção; (b) (In)visibilidade da paternidade na discussão sobre parentalidade adotiva; (c) Homoparentalidade: significados da tecnologia reprodutiva à adoção. Os estudos se debruçam sobre reflexões a respeito da parentalidade em casais heterossexuais e homossexuais, bem como ressaltam o modo como esses casais exercem seus papéis parentais. Conclui-se que entender o modo como é feito o exercício dos papéis parentais nessas diferentes realidades possibilita a compreensão das diferentes configurações familiares, abrindo mais espaço para as famílias por adoção. Recomenda-se ampliação das discussões de gênero, afim de propiciar questionamentos e tensões para esse cenário, dialogando com diferentes perspectivas desenvolvimentais e clínicas.

Palavras-chave: Adoção, gênero, identidade de gênero, homoparentalidade.

RESUMEN

El presente estudio tuvo por objetivo comprender cómo la categoría género emerge en los estudios sobre adopción en el contexto brasileño. La pregunta orientadora fue: ¿de qué forma las investigaciones realizadas en el contexto de la adopción abordan las cuestiones de género? Se realizó una revisión integrativa de la literatura en las bases de datos LILACS, SciELO y PePISC publicados en el período entre 2007 y 2017. Se seleccionaron 17 artículos, a partir de los cuales se constituyeron tres categorías de análisis (a) El ejercicio de la maternidad en el contexto de la adopción; (b) La (In) visibilidad de la paternidad en la discusión sobre parentalidad adoptiva; (c) Homoparentalidad: significados de la tecnología reproductiva a la adopción. Los estudios se centran en reflexiones acerca de la parentalidad en parejas heterosexuales y homosexuales, así como resaltan el modo en que estas parejas ejercen sus papeles parentales. Se concluye que entender cómo se ejerce papeles parentales en esas diferentes realidades posibilita la comprensión de las diferentes configuraciones familiares, abriendo más espacio para las familias por adopción. Se recomienda ampliar las discusiones de género, a fin de propiciar cuestionamientos para ese escenario, dialogando con diferentes perspectivas de desarrololo y clinicas.

Palabras clave: Adopción, género, identidad de género, homoparentalidad.

During the 1980s and 1990s it was possible to consider family structures as the stage for various modifications concerning their arrangements, dynamics and ways of organizing their members. Such changes were the result of complex social and cultural transformations, making it impossible to refer to the family as a standardized model, given its different forms of configuration (Dias, 2011; Uziel, 2007). These changes included the reduction of the average number of children, an increase in the number of single people, a reduction in the number of family members, an increase in recomposed families as a result of an increase in the number of divorces, an increase in domestic partnerships, single-parent and multi-parent families and, more recently, families with same-sex couples (Dias, 2011; Uziel, 2007). Given this scenario, it becomes possible to question the traditional model of the bourgeois (patriarchal) nuclear family in order to legitimize several possible formats of this institution.

Considering these transformations, mainly due to social, cultural and economic moderni-zation, changes can also be seen in relation to family functioning, with emphasis on those related to the roles of each gender (Neves, 2013). Men and women exert socially predefined roles within a particular culture and historical context that determine the ways in which individuals experience their social and family relationships (Bourdieu, 2007). In view of these changes, especially the greater inclusion of women in the labor market in line with the engagement of men in the division of household tasks (Neves, 2013), it is possible to observe a relaxation, albeit relative, in tasks socially assigned to the question of gender.

However, it is important to highlight the family institution as a locus of (re)produc-tion of gender stereotypes, both through transgenerational transmission and the social constructions by which they are supported, promoting inequalities and unleashing consequences regarding gender roles and the way in which they are reproduced in society. Regarding gender inequalities, no matter how much some social movements continually struggle to reduce them, the presence of rigid gender values and stereotypes that directly influence individual and collective subjectivities can be observed (Tardin, Barbosa, & Leal, 2015).

Concerning these values and the way they are presented in the family institutions, it is important to highlight the pressure regarding motherhood and the responsibilization of the woman for domestic and care activities, especially for children and older adults, among others (Pinheiro, Galiza, & Fontoura, 2009). Accordingly, more equitable concepts regarding gender roles in the family context are still in dispute and under construction.

From this perspective, the importance of gender representations articulated to the exercise of parenthood can be considered (Gross, 2009), with this concept being understood as a set of psycho-affective processes that develop and integrate in the parents, referring to the dynamic aspect and process of the experience of constituting a father and/or mother, as well as the demands arising from these functions (Silva, 2011). Parenthood, whether adoptive or consanguineous, is constructed from discourses and practices, so that parental roles should not be seen as particular phenomena of the relationships established within families, but as a social process (Andrade, Costa, & Rossetti-Ferreira, 2006).

Planning to construct a family that generates offspring remains present, however, not in a "totalizing" way in these different constitutions. The traditional concepts regarding this institution value parenthood, which could explain the motivations regarding the desire to have a child (Otuka, Scorsolini-Comin, & Santos, 2012). This planning has become even more feasible for its different configurations through the advances in assisted reproduction and new legislation regarding adoption, which allow access to parenthood for those that are biologically unable to generate offspring (Uziel, 2007). Fonseca (2006) argued that there are several symbols other than blood that refer to the idea of parentage, creating a connectivity based on the deep and lasting relationship between its members, as in the case of adoptive families.

Adoption started to be recognized in society and gained spaces for discussion, broadening the view regarding the family constitution, being currently recognized as one of the possibilities of family constitution based on affective bonds (Schettini, Amazonas, & Dias, 2006). It should be noted that adoption is related to a protective measure and to the possibility of providing the child or adolescent with an adequate environment for their development and family life. Thus, it is defined as the possibility of establishing legitimate bonds of affiliation with an unknown person, duly guaranteed by the legislation (Weber, 2010).

The Statute of Children and Adolescents (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescentes [ECA], 1990), in consonance with the Federal Constitution, does not delimit the family to the presence of both sexes as a parental couple. According to Brunchaft (2012), after the approval of the Direct Unconstitutional Action-ADI 4277/2011 in the Federal Supreme Court, in Brazil the civil union between people of the same sex was recognized, identifying it as a Family Entity. According to the ECA (1990) and the New Law of Adoption (Law No. 12.010, 1996), sexual orientation should not be a criterion of exclusion or preference for adoption candidates, that is, there is no prohibition on adoption by same-sex couples.

Recognition of parenthood and filiation can also be influenced by the political and subjective dimension (Tarnovski, 2012). Thus, the importance of understanding the gender roles - social and historically constructed - related to adoption is evident, making it possible to apprehend the changes and transformations present in society. To understand how these dimensions are explored, or not, in the scientific literature offers clues about how gender can be incorporated into the discussion agenda regarding adoption in the country and the legal recommendations surrounding the qualification processes of postulants to adoption. Within this context, the aim of this study was to understand how the gender category emerges in studies regarding adoption in the Brazilian context.

Method

Study Type

This was an integrative review of the scientific literature. According to Scorsolini-Comin (2014) and Souza, Silva, and Carvalho (2010), the integrative review aims to present a synthesis of several published studies and to evidence general conclusions about a specific area of study. The guiding question of the present study was formulated from the PICO strategy (Santos, Pereira, & Nobre, 2007), which represents an acronym for "Patient", "Intervention", "Comparison" and "Outcome". Based on this strategy, the guiding question of this study was: "How do studies performed in the context of adoption (O) that refer to children, parents and professionals (P) address gender issues (I)?" It should be noted that since the study objective was not a comparison, the PICO strategy was implemented without the "C" (comparison) criterion.

Databases

The searches were performed in the LILACS, SciELO and PePISC electronic data-bases, using combinations that covered the theme of this review: adoption, gender and parenthood. In this way, the combinations of the descriptors used were: adoption and gender, adoption and gender identity, adoption and interpersonal relations, adoption and feminism, adoption and sexuality, adoption and stereotypes, adoption and motherhood, adoption and fatherhood, adoption and parenthood and adoption and same-sex parenthood. In addition to the English Language, the study was also carried out with the same combinations in the Portuguese Language.

Inclusion Criteria

The articles selected met the following criteria: (a) published in scientific journals, since they are studies that go through the process of peer evaluation and review; (b) published in Portuguese and/or English; (c) published between January 2007 and December 2017; (d) available in full; (e) encompassing the discussion on adoption and gender, together; and (f) reporting practices and/or studies conducted in the Brazilian context, even if the results were published in journals from abroad. The choice for the exclusivity of national works was due to the fact that the adoption laws in each country differ, which, in turn, makes comparisons between different contexts difficult.

Exclusion Criteria

The following were excluded: (a) theses, dissertations, monographs, books, chapters, abstracts, obituaries, reviews, letters, annals of congresses and editorials; (b) publications dis-tant from the theme and that did not answer the guiding question; (c) articles that did not portray the Brazilian context.

Procedures

The search was performed separately by the authors of the article, which made it possible to use the criterion of independent judges. The study phases were: (1) bibliographic survey in the electronic databases, carried out over two days in the second half of 2017; (2) reading and analysis of the titles and abstracts of the materials found; (3) application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) selection of articles from the complete texts; (5) exclusion of repeated articles; (6) composition of the corpus from the articles retrieved that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria; (7) composition of the database in Excel, characterizing the main information of each study: title, authors, year, type of study, journal, institution of the authors, objectives, main results and main conclusions. In order to carry out the strategy of independent judges, phases 1 to 4 were performed individually by the first two authors, followed by a comparison of the data collected, with the other steps being performed by all the authors.

Data Analysis

The articles selected to compose this review study were categorized in an Excel spreadsheet for analysis, according to the following data: authors, year, type of study, journal, objectives, main results and main conclusions. The corpus was read and analyzed in its entirety and, from the contents covered in each production, the following categories were constructed to group the findings of the retrieved literature: (a) Exercise of motherhood in the context of adoption; (b) (In)visibility of fatherhood in the discussion about adoptive parenthood; (c) Same-sex parenthood: meanings of reproductive technology for adoption.

Results

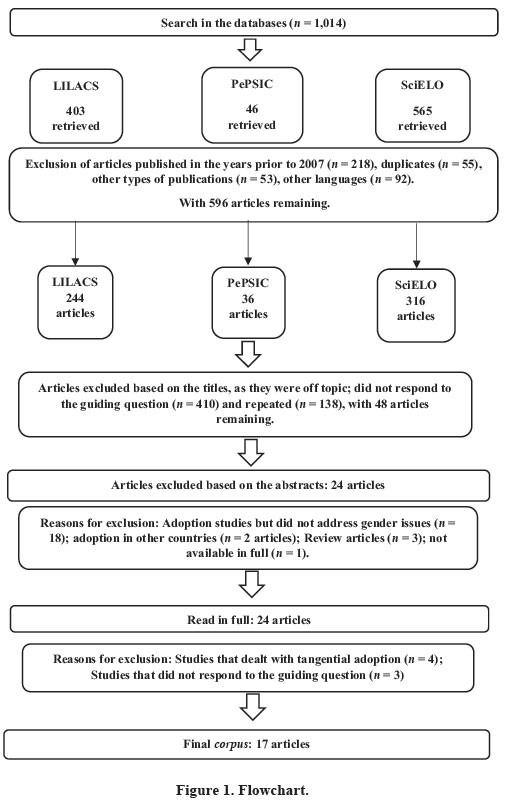

The searches performed in the databases using the selected descriptors resulted in 1,014 articles (LILACS=403, SciELO=565, PePSIC=46). From the inclusion and exclu-sion criteria, and by taking out repeated articles, 17 articles were selected and analyzed in full, which compose the corpus of the present review, represented in a Flowchart format in Figure 1.

Table 1 summarizes the main aspects of the retrieved articles according to title, author, year of publication, type of study and journal. All the studies were written in the Portuguese language, considering that the productions in the English language represented international realities that are not compatible with that of Brazil, given that the laws of each country occur in a varied way, according to their social, political, economic and cultural contexts.

The majority of the selected studies were published in the years 2015 (n=5) and 2016 (n=4), the others were published in 2008 (n=1), 2009 (n=3), 2012 (n=1), 2013 (n=1) and 2014 (n=2). In relation to the type of study, 15 articles are empirical, only 1 (Cerqueira-Santos & Santana, 2015) was based on the quantitative methodology and the rest on qualitative methodology, except for 2 articles that were theoretical (Fonseca, 2008; França, 2009).

In relation to the publishing journals, the greatest occurrence was in the Psicologia e Sociedade (n=2) and Pensando Famílias (n=2) journals. These journals present a thematic focus in the interface between Psychology and society and works related to the areas of couples and families, respectively. The majority of the studies (n=15) were indexed in journals of the Psychology area, with only two studies being present in journals of other areas of knowledge.

In general, the articles discussed three main themes: motherhood, fatherhood and same-sex parenthood. Table 2 presents a description of the main objectives addressed by these studies, in which the grouping was based on the convergences, highlighting the gender theme in the exercise of parenting.

Discussion

Exercise of Motherhood in the Context of Adoption

Although there have been changes and ruptures in certain historical moments regarding the role of women, values and expectations considered traditional regarding the woman's place can still be observed. One of these aspects concerns motherhood and its association with the feeling of completeness and fulfillment in women's lives (Biasoli-Alves, 2000). According to Castro (2002) and Motta (2001), motherhood is culturally defined as an unconditional love, acting as a mechanism that naturalizes the social role of the women and imputes responsibility for caring for and educating her children.

In five studies there are results that corroborate this idealization of motherhood (Lage et al., 2014; Mahl et al., 2012; Maux & Dutra, 2009; Sonego & Lopes, 2009), in which women were interviewed regarding adoptive motherhood, revealing traditional representations of family and motherhood, indicating that the family is made up of father, mother and children and that this institution only reaches completeness when the parenthood is solidified. It should be noted that this composition, according to what is presented in the statements of the participants of these studies, is based on a heteronormative perspective of these roles, establishing rigid models of parenthood that delegate to the man (father) and the woman (mother) specific functions according to their gender. The concept of motherhood related to what Badinter (1985) called "the myth of maternal love" (supposedly unconditional love for the child born of instincts and the female biological imperative) was also evidenced.

Regarding the motivations for performing adoption, some of the studies retrieved address the issue of infertility (male or female) as one of the main reasons. It was possible to observe that traditional concepts regarding family and motherhood served as the background for these couples to seek adoption, a solution to the biological impossibility of pregnancy, as well as recognition of the exercise of parenthood (Lage et al., 2014; Mahl et al., 2012; Maux & Dutra, 2009; Sonego & Lopes, 2009). In the study by Maux and Dutra (2009) on fertile women who chose to adopt because of their infertile spouses and in the study by Mahl et al. (2012) on female infertility, characteristics associated with the social pressure related to motherhood, exercised by the extended family and/or by the social group of these women were evidenced. In this sense, the social constructions linked to the representations of motherhood that naturalize the idea that being a woman is, necessarily, being a mother, exert a strong influence in making the decision to have children, whether they are consanguineous or adopted. Furthermore, when motherhood does not occur, these women feel the social pressure of these representations that regard motherhood as the destiny of the woman (Mahl et al., 2012; Maux & Dutra, 2009; Patias & Baues, 2009).

On one hand there is the traditional perspective which is due to the existence of delimited roles, assigning marriage and motherhood to the woman, while on the other, the female figure is developing new functions related to the labor market and professional achievements, as well as other personal projects not restricted to motherhood (Lage et al., 2014; Mahl et al., 2012; Maux & Dutra, 2009; Sonego & Lopes, 2009). Thus, women end up exercising a double working day and begin to contribute financially (often as the main providers), which alters the exercise of power in families, however, they continue to perform the household tasks (Borlot & Trindade, 2004; Fiorin, Patias, & Dias, 2011; Patias & Buaes, 2012).

When thinking about the historical context that permeates these concepts regarding the woman and motherhood, it is possible to emphasize the influence of the feminist movements, the development of contraceptive methods (contraceptive pill) and the New Reproductive Technologies (NTR), which contribute to changes in motherhood that, on the face of it, is no longer seen as the destiny for women (Maux & Dutra, 2009). However, in the Brazilian context, the education of women and the population as a whole still carries significant influences from the traditional family model that places its constitution (from marriage and the generation of children) as an indispensable project (Borlot & Trindade, 2004; Souza & Ferreira, 2005; Trindade & Enumo, 2002).

Among the main results obtained in the studies with female participants, discourses were observed that confer greater social recognition to motherhood than any other role they may play, as well as expectations for the development of adopted children and the exercise of motherhood in an idealized way, without duly considering the possible difficulties and mishaps arising from this process. Another significant aspect to be highlighted is the experience of some type of suffering for some of these women due to not being able to become pregnant (Lage et al., 2014; Mahl et al., 2012; Maux & Dutra, 2009; Sonego & Lopes, 2009).

According to Otuka et al. (2012), the feeling of exclusion faced with the non-fulfillment of motherhood seems to only dissolve when the women become mothers, given that, culturally, the family constitution legitimizes itself from the "marriage-children" pathway, a fact that could be evidenced in the studies covered in this review (Lage et al., 2014; Mahl et al., 2012; Maux & Dutra, 2009; Sonego & Lopes, 2009). Thus, there is still the concept that for the family to be complete there is a need to have children (Patias & Buaes, 2012). In this way, it becomes possible to infer that discourses concerning motherhood and the family dictate and crystallize the constitution of the female. It can be perceived that these conventions are little questioned by the people, attributing the natural character to motherhood, this being intrinsic to healthy women, which generates stigmatization for those who cannot or do not wish to exercise motherhood.

Based on this assumption, it is understood that this concept can contribute to the dissemination of prejudices in relation to the mothers that put their children up for adoption (Zanardo, Teixeira-Filho, & Ribeiro, 2014). In the study by Maux and Dutra (2009), the participants discussed the prejudice against women that put their children up for adoption when reporting that the very fact of generating the child already characterizes them as mothers, that is, these women are require to provide their offspring with care and dedication, justified by unconditional and innate love. This view again refers to the idea of the "myth of maternal love" discussed by Badinter (1985), which reinforces the stigmatization of women that choose to put their children up for adoption and women who choose not to have children.

In these sociohistorical marks an "ideal" female identity is created, being determined by what is socially understood as common and expected of all women. According to Moreira and Dutra (2006), this identity can be understood as a subjugated subjectivity that must accompany a given script, that is, an a priori way of life that determines the proper way of being in the world as a woman.

(In)Visibility of Fatherhood in the Discussion about Adoptive Parenthood

Although certain tasks and responsibilities, attributed to each gender, have been modified and made flexible over the last decades, the construction of the meaning of "being a mother" and of "being a father" in contemporary times still shows itself to be impregnated with stereotypes and social demands. Although the subject of fatherhood is receiving more emphasis in gender studies and also in those concerning same-sex parenthood, it should be emphasized that in the theories about child development, the father figure has been less discussed compared to the maternal role (Colleti & Scorsolini-Comin, 2015; Luz & Berni, 2010).

This reality is exemplified by the small number of articles about fatherhood found in this review. Among these, with the exception of those related to same-sex adoptive parenthood (addressed in the third category of analysis of this review), only two had men as the study subjects (Machado et al., 2015; Silva & Santos, 2014).These articles focused on discourses of women to understand the process of construction of the parenthood of adoptive families and the adoption process itself (Lage et al., 2014; Mahl et al., 2012; Maux & Dutra, 2009; Sonego & Lopes, 2009).

Accordingly, the relative invisibility of the male perspective in these processes stands out, which ends up reiterating the idea of the female as the locus and protagonism of the activities related to the care of the children. According to Borsa and Nunes (2011), both the positioning of child development studies and the perpetuation of gender stereotypes in society contribute to the greater interest in studies on the "mother/motherhood" theme, to the detriment of the "father/fatherhood" theme.

Conversely, contemporaneity is requiring more participatory fatherhood, regarding both domestic tasks and affective and educational involvement with the children. Although in a reduced form, some studies on this theme (Botton, Cúnico, Barcinski, & Strey, 2015; Campos, De Tilio, & Crema, 2017; Medina et al., 2011) demarcate the questioning of stereotypes that delimitated the man to the place of an authoritarian and insensitive father that does not show affection for his children and has little effective participation in the parental responsibilities. According to Fonseca (2004) and Perucchi and Beirão (2007), although there are stereotyped trends in the ways of exercising masculinity within the context of parenthood, the diversity that these models have been presenting should be mentioned.

In order to comprehend the experience of being a father through adoption and to identify how the father experiences fatherhood, one of the articles retrieved (this being a case study) portrays the positioning of this subject faced with fatherhood. This participant reported being responsible for the daily care of the adopted children (meals, bathing, taking and picking up from school and recreational moments), as well as showing himself to be the one responsible for imposing limits and scolding, indicating the perspective of man as the moral provider and representative of the law. It is suggested that this statement, although individualized, indicates possible ruptures in the hegemonic model of masculinity that distances the man from the direct care of the children (Silva & Santos, 2014).

Taking a counterpoint to other areas of research, it is important to recognize that the reduced number of studies and interventions aimed at the male public is reproduced in different sectors, such as health actions and public policies directed toward men (Couto & Gomes, 2012; Gomes et al., 2011). Given this scenario, which is not limited to the field of adoption, it is necessary to understand the processes that involve the exercise of masculinity (among them, fatherhood) from the discursive practices of those involved, in order to better understand and accept this requirement (Costa & Rossetti-Ferreira, 2007). Exploring the meanings produced by adoptive parents about fatherhood only becomes possible from the moment these subjects are placed as protagonists in this category of analysis. Thus, there is a need for studies that favors a reflection on adoptive fatherhood and its construction process, since few studies investigate becoming an adoptive father.

Same-sex Parenthood: Meanings of Reproductive Technology for Adoption

In the Brazilian context, the legalization of stable marriages of same-sex couples only took place in the year 2011 (i.e. support for this population to be recognized as a family according to the law; Brunchaft, 2012). The study by Rosa et al. (2016) highlights that the establishment of rules and norms is present in all types of unions, as well as certain types of social demands, among these the expectation of the generation of descendants. Still according to this study, its participants reported the lack of an alternative family model, with the family pattern being predominantly characterized as monogamous, nuclear, and centered on the heterosexual parental couple. This pattern mainly involves characteristics of heteronormative relationships, understanding this concept as social expectations, demands and obligations that are derived from the assumption of heterosexuality as the natural (Chambers, 2003).

Regarding the articles analyzed in this review, 10 discussed aspects related to same-sex parenthood. According to Amazonas et al. (2013) this theme is gaining greater recognition, both in society and in terms of being a research object in the academic environment. In 3 studies selected on this topic, motivation was present in only one partner, with the other not immediately identifying with the parental role. When considering the gender differences, male couples were characterized by reporting indi-vidual wishes regarding the desire to have children, while female couples highlighted the parental project as a mutual desire (Amazonas et al., 2013; Machin, 2016; Rosa et al., 2016).

The studies of Fonseca (2008), Machin (2016) and Vitule et al. (2015) portrayed two possibilities for same-sex parenthood: reproductive treatments and adoption. Thus, in couples formed by women, the predominant choice is the use of reproductive technologies, which is a resource associated with fertility, motherhood, heredity, consanguineous reproduction and parentage. The statements of the interviewees were permeated with the desire to have a biological child and to go through the experience of pregnancy and breastfeeding. Another aspect highlighted in the studies was the use of ROPA (Reception of Oocytes from Partner) as a reproductive technology, in which both can be recognized as mothers, one of them being responsible for the donation of the egg and the other for the pregnancy; thus, the biological bond would affirm the social bond, with the motherhood being effectively recognized by them.

The male couples also presented statements that value the biological bond, reporting the desire to have a consanguineous child. However, they observed this resource with some impediments and concerns. Although these fathers have an interest in enabling fatherhood via strategies that guarantee consanguinity, there is a need for the pregnancy to be performed by a woman, therefore the participants in these studies reported the fear of the child-genitor bond that could be established, as well as the legal implications arising from the process. In this way, they believed in the preponderance of the biological bond over the social (adoption), and feared the loss of the child to the biological mother. Thus, these couples sought adoption as a way of becoming parents (Machin, 2016; Vitule et al., 2015).

The study by Vitule et al. (2015) addressed aspects related to the desired profiles of children for adoption by same-sex couples, identifying the differentiation regarding preferences according to the gender of the couple. Adoption of older children is valued by male couples, whereas women prefer younger children. In the first case, Machin (2016) reported that male couples prefer the child to be of an age that allows the couple to perform care without reliance on third parties, seeking to bond with the child during the adoption process. Whereas, women opt for the adoption of babies because they want to go through caring for a baby and experience aspects related to motherhood. In addition, there were no reports of preferences regarding gender, color/ethnicity or type of illness in same-sex parental adoption. These adopters are characterized by a more flexible profile when compared to heterosexual couples, not presenting the desire to adopt a child with characteristics similar to their own.

Another important issue among the selected articles is related to the gender roles in same-sex parental adoption, as well as their consequences for the development of the child (Cerqueira-Santos & Bourne, 2015, 2016; Cerqueira-Santos & Santana, 2015; França, 2009; Meletti & Scorsolini-Comin, 2015; Rosa et al., 2016). According to França (2009) and Rosa et al. (2016), there is a question in relation to the rearing of children by same-sex couples regarding the performance of maternal and paternal roles. In the study by Cerqueira-Santos and Santana (2015), it was observed that this problem is in the imaginary of professionals who work directly with adoption processes. The study findings identified the concept of Law and Social Work students in relation to same-sex parental adoption, highlighting that the majority of the interviewees were not in favor of this type of adoption, their main argument being that the child would not have healthy development due to not having distinct parental role models. On this subject, França (2009), Meletti and Scorsolini-Comin (2015) and Rosa et al. (2016) argued that these functions do not necessarily have to be fulfilled by the figure of the man or the woman, but by individuals who exercise them according to their identifications.

Prati and Koller (2011) reported that the insertion of a child into the family, whether consanguineous or adoptive, causes the environ-ment to change and new strategies to be triggered. In this sense, the execution of parental roles will depend on how the parents work together and establish their dynamics and divisions within the family context. Rosa et al. (2016) indicated that in same-sex couples, there is often a division of tasks determined by the availability of each spouse. Similar results were reported by Meletti and Scorsolini-Comin (2015), identifying couples with non-stereotyped behaviors in which the division of tasks respects the availability and suitability of each partner.

The study focused on the particularities of adoption and, highlighting same-sex adoptions, two studies (Amazonas et al., 2013; França, 2009) addressed some specificities of this process: the difficulty in revealing the sexual orientation of the parents to the adopted children and the prejudices existing in society regarding this type of family configuration. In relation to the first aspect, it was highlighted that the parents did not usually disclose their sexual orientation for fear of discrimination and prejudice, with them expressing the difficulty of revealing this to the child, due to both the child's judgment and capacity for understanding, indicating the fear of not being respected and losing the love of the child.

While these studies showed the fear of the parents related to choosing to tell their children about their sexual orientation, the importance to the child of this early disclosure, as well as the child's ability to understand and accept this characteristic was also highlighted. Amazonas et al. (2013), emphasized that this revelation happens in the quotidian, through the behaviors and performances of the parents, regardless of the sexual orientation, and they should provide a stable and affective environment for the child.

Meletti and Scorsolini-Comin (2015) argued that same-sex couples are worried about their children suffering because they belong to a homoaffective family, considering the discrimination and prejudice. According to the studies (Amazonas et al., 2013; França, 2009; Meletti & Scorsolini-Comin, 2015), this is a theme that couples evaluate when deciding on same-sex parenthood. Therefore, the studies retrieved highlighted important themes about same-sex parenthood, above all, related to the fact that bringing up children in homoaffective homes does not differ when compared to the upbringing in so-called conventional families. Same-sex couples prioritize the quality of parental care for the development of their children, are available and attentive to the needs of the child and aim to always provide quality care. Thus, the importance is highlighted of considering same-sex parent adoption as a right of children to family life and of same-sex couples to exercise parenthood.

Final Considerations

In seeking to comprehend how the studies carried out in the context of adoption address the issues of gender, it was possible to perceive in this review that this theme is acquiring more space in the Brazilian scientific literature. In general, the reality presented in the articles favored reflections on how socially constructed gender roles determine the ways of performing the parental functions, whether constituted by homosexual or heterosexual couples.

As much as contemporary society presents transformations occurring in family settings, the traditional and heteronormative model of this institution is still the reference. It was possible to highlight hegemonic discourses that valorize the innate maternal love, as well as the idealization of motherhood as a form of completeness for women. It is important to highlight the need for more studies that addresses the meanings produced by adoptive parents regarding fatherhood, understanding that the lack of research in this sector can indicate traits present in the society that grant the woman the function of raising and caring for the children and the man the external environment and provider roles.

Considering the studies on same-sex parenthood, it is important to understand how these couples exercise their parental roles, in order to broaden the meanings produced regarding the new family configurations, also serving as a way to minimize the consequences arising from the possible discriminations that these families may suffer. In short, this review made possible reflections that are not restricted only to the adoptive family, but to any kind of family configuration. It is necessary to emphasize that these different compositions allow fissures in the traditional model of family and, in doing so, legitimize different forms of constitution, not only of the families, but also of the exercise of the parental roles.

In addition to these points, the importance is emphasized of expanding these gender discussions, in order to promote questions and tensions in this scenario, exploring authors, approaches and references that can dialogue with the developmental and clinical perspectives that are considered in the majority of studies on the subject in Brazil. It is recognized that these investigations could be more comprehensive when addressing more complex aspects that involve both adoption and parenthood, making the dialogue with current gender issues more intimate. This review also demonstrates the urgent need to explore other contexts beyond the Brazilian scenario, although the articulation with the legislation of each country is fundamental in this area, in order to favor a comprehension that is contextualized and attentive to the way in which these processes enable greater or lesser openness for the considerations that surround gender.

References

Amazonas, M. C. L. A., Veríssimo, H. V., & Lourenço, G. O. (2013). A adoção de crianças por gays. Psicologia & Sociedade, 25(3),631-641. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3093/309329764017.pdf [ Links ]

Andrade, R. P., Costa, N. R. A., & Rossetti-Ferreira, M. C. (2006). Significações de paternidade adotiva: Um estudo de caso. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 16(34), 241-252. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3054/305423754012.pdf [ Links ]

Badinter, E. (1985). Um amor conquistado: O mito do amor materno (4th ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Nova Fronteira. [ Links ]

Biasoli-Alves, Z. (2000). Continuidades e rupturas no papel da mulher brasileira no século XX. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 16(3),233-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722000000300006 [ Links ]

Borlot, A. M., & Trindade, Z. A. (2004). As tecnologias de reprodução assistida e as representações sociais de filho biológico. Estudo de Psicologia (Natal), 9(1),63-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2004000100008 [ Links ]

Borsa, J., & Nunes, J. (2011). Aspectos psicossociais da parentalidade: O papel de homens e mulheres na família nuclear. Psicologia Argumento, 29(4),31-39. Retrieved from https://periodicos.pucpr.br/index.php/psicologiaargumento/article/view/19835/19141 [ Links ]

Botton, A., Cúnico, S. D., Barcinski, M., & Strey, M. N. (2015). Os papéis parentais nas famílias: Analisando aspectos trangeracionais e de gênero. Pensando Famílias, 19(2),43-56. Retrieved from http://repositorio.pucrs.br/dspace/bitstream/10923/9252/2/Os_papeis_parentais_nas_familias_analisando_aspectos_transgeracionais_e_de_genero.pdf [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (2007). A dominação masculina. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Bertrand Brasil. [ Links ]

Brunchaft, M. E. (2012). A temática das uniões homo afetivas no Supremo Tribunal Federal à luz do debate Honneth-Fraser. Revista Direito GV, 8(1),133- 156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1808-24322012000100006 [ Links ]

Bueno, R. K., Vieira, M. L., & Crepaldi, M. A. (2016). Paternidade no contexto da adoção. Pensando em Famílias, 20(1),57-67. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/penf/v20n1/v20n1a05.pdf [ Links ]

Campos, M. T. A., De Tilio, R., & Crema, I. L. (2017). Socialização, gênero e família: Uma revisão integrativa da literatura científica. Pensando Famílias, 21(1),145-161. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/penf/v21n1/v21n1a12.pdf [ Links ]

Castro, A. M. O. (2002). Pessoa, gênero e família: Uma visão integrada do Direito. Porto Alegre, RS: Livraria do Advogado. [ Links ]

Cerqueira-Santos, E., & Bourne, J. (2015). Papeis de gênero nas brincadeiras de faz- de- conta de crianças adotadas por casais do mesmo sexo. Contextos Clínicos, 8(1),38-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.4013/ctc.2015.81.04 [ Links ]

Cerqueira-Santos, E., & Bourne, J. (2016). Estereotipia de gênero nas brincadeiras de faz de conta de crianças adotadas por casais homoparentais. Psico-USF, 21(1),125-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712016210111 [ Links ]

Cerqueira-Santos, E., & Santana, G. (2015). Adoção homoparental e preconceito: Crenças de estudantes de Direito e Serviço Social. Temas em Psicologia, 23(4),873-885. http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2015.4-06 [ Links ]

Chambers, S. J. (2003). Telepistemology of the Closet; Or, the Queer Politics of Six Feet Under. Journal of American Culture, 26(1),24-41. doi: 10.1111/1542-734X.00071 [ Links ]

Colleti, M., & Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2015). Pais de primeira viagem: A experiência da paternidade na meia-idade. Psico, 46(3),374-385. http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2015.3.19335 [ Links ]

Costa, N. R. A., & Rossetti-Ferreira, M. C. (2007). Tornar-se pai e mãe em um processo de adoção tardia. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 20(3),425-434. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/188/18820310.pdf [ Links ]

Couto, M. T., & Gomes, R. (2012). Homens, saúde e políticas públicas: A equidade de gênero em questão. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, 17(10),2569-2578. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232012001000002 [ Links ]

Dias, M. O. (2011). Um olhar sobre a família na perspectiva sistêmica: O processo de comunicação no sistema familiar. Gestão e Desenvolvimento 19(1),139-156. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10400.14/9176 [ Links ]

Fiorin, P. C., Patias, N. D., & Dias, A. C. G. (2011). Reflexões sobre a mulher contemporânea e a educação dos filhos. Revista Sociais e Humanas, 24(2),121-132. Retrieved from https://periodicos.ufsm.br/sociaisehumanas/article/view/2880/2859 [ Links ]

Fonseca, C. (2004). A certeza que pariu a dúvida: Paternidade e DNA. Revista de Estudos Feministas, 12(2),13-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-026X2004000200002 [ Links ]

Fonseca, C. (2006). Da circulação de crianças à adoção internacional: Questões de pertencimento e posse. Cadernos Pagu, 26,11-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-83332006000100002 [ Links ]

Fonseca, C. (2008). Homoparentalidade: Novas luzes sobre o parentesco. Revista Estudos Feministas, 16(3),769-783. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-026X2008000300003 [ Links ]

França, M. R. C. (2009). Famílias homoafetivas. Revista Brasileira de Psicodrama, 17(1),21-33. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/psicodrama/v17n1/a03.pdf [ Links ]

Gomes, R., Moreira, M. C. N., Nascimento, E. F., Rebello, L. E. F. S., Couto, M. T., & Scharaiber, L. B. (2011). Os homens não vêm! Ausência e/ou invisibilidade masculina na atenção primária. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, 16(1),983-992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000700030 [ Links ]

Gross, M. (2009). The desire for parenthood among lesbians and gay men. In D. Marre & L. Briggs (Eds.), International Adoption. Global Inequalities and the Circulation of Children (pp. 87-102). New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Lage, S. R., Santos, I. M. M., & Nazareth, I. V. (2014). Narrativa de vida de mulheres que amamentaram seus filhos adotivos. Revista Rene, 15(2),249-256. doi: 10.15253/2175-6783.2014000200009 [ Links ]

Law No. 12.010. (1996, August 03). Dispõe sobre adoção. Retrieved from http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/lei/112010.htm [ Links ]

Luz, A. M., & Berni, N. I. (2010). Processo da paternidade na adolescência. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 63(1),43-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672010000100008 [ Links ]

Machado, R. N., Féres-Carneiro, T., & Magalhães, A. S. (2015). Parentalidade adotiva: Contextualizando a escolha. Psico, 46(4),442-451. http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2015.4.19862 [ Links ]

Machin, R. (2016). Homoparentalidade e adoção: (Re) afirmando seu lugar como família. Psicologia & Sociedade, 28(2),350-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-03102016v28n2p350 [ Links ]

Mahl, F. D., Jaeger, F. P., Patias, N. D., & Dias, A. C. G. (2012). Enquanto a maternidade não vem: A infertilidade e apressãosocial como pano de fundo para a adoção. Pensando Famílias, 16(2),85-102. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275336957_ [ Links ]

Maux, A. A. B., & Dutra, E. (2009). Do útero à adoção: A experiência de mulheres férteis que adotaram uma criança. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 14(2),113-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2009000200004 [ Links ]

Medina, J. L. V., Fuentes, N. I. G. A. L., Escobar, S. G., Valdez, V. D. A., Farías, P. L., Guerrero, I. A. M., Calderón, L. M., & Manjarrez, A. A. S. J. (2011). Orientación que transmitenlos padres a sus hijos adolescentes. Revista Mexicana de Orientación Educativa, 8(20), 2-9. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/remo/v8n20/a02.pdf [ Links ]

Meletti, A. T., & Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2015). Conjugalidade e expectativas em relação à parentalidade em casais homossexuais. Revista Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 17(1),37-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.15348/1980-6906/psicologia.v17n1p37-49 [ Links ]

Moreira, A. R., & Dutra, E. (2006). Perspectiva sócio-histórica e abordagem humanista-existencial: Reflexões sobre o conceito de subjetividade. Vivência, 31,49-59. Retrieved from http://www.cchla.ufrn.br/Vivencia/sumarios/31/PDF%20para%20INTERNET_31/cap%2002_ANA%20REGINA_E_ELZA%20DUTRA.pdf [ Links ]

Motta, M. A. P. (2001). Mães abandonadas: A entrega de um filho para a adoção. São Paulo, SP: Cortez. [ Links ]

Neves, M. A. (2013). Anotações sobre trabalho e gênero. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 43(149),404-421. http://dx.doi.org./10.1590/S0100-15742013000200003 [ Links ]

Otuka, L. K. Scorsolini-Comin, F., & Santos, M. A. (2012). Adoção suficientemente boa: Experiência de um casal com filhos biológicos. Psicologia Teoria e Pesquisa, 8(1),55-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722012000100007 [ Links ]

Patias, N. D. P., & Buaes, C. S. (2009). Não têm filhos? Por quê? DisciplinariumScientia, 10(1),121-133. Retrieved from https://www.periodicos.unifra.br/index.php/disciplinarumCH/article/view/1697/1601 [ Links ]

Patias, N. D. P., & Buaes, C. S. (2012). "Tem que ser uma escolha da mulher"! Representações de maternidade em mulheres não-mães por opção. Psicologia & Sociedade, 24(2),300-306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822012000200007 [ Links ]

Perucchi, J., & Beirão, A. M. (2007). Novos arranjos familiares: Paternidade, parentalidade e relações de gênero sob o olhar de mulheres chefes de família. Revista Psicologia Clínica, 19(2),57-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-56652007000200005 [ Links ]

Pinheiro, L., Galiza, M., & Fontoura, N. (2009). Dossiê retrato das desigualdades de gênero e raça - Novos arranjos familiares, velhas convenções sociais de gênero: A licença - parental como política pública para lidar com essas tensões. Estudos Feministas, 17(3),851-859. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-026X2009000300013 [ Links ]

Prati, L. E., & Koller, S. H. (2011). Relacionamento conjugal e transição para a coparentalidade: Perspectivas da psicologia positiva. Psicologia Clínica, 23(1),103-118. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/pc/v23n1/a07v23n1.pdf [ Links ]

Rosa, M. J., Melo, A. K., Boris, G. D. J. B., & Santos, M. A. (2016). A construção dos papéis parentais em casais homoafetivos adotantes. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 36(1),210-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703001132014 [ Links ]

Santos, C. M. C., Pereira, C. A. M., & Nobre, M. R.C. (2007). A estratégia PICO para a construção da pergunta de pesquisa e busca de evidências. Revista Latino-americana de Enfermagem, 15(3),1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692007000300023 [ Links ]

Schettini, S. M. S., Amazonas, M. C. L. A., & Dias, C. M. S. B. (2006). Famílias adotivas: Identidade e diferença. Psicologia e Saúde, 11(2),285-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722006000200007. [ Links ]

Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2014). Guia de orientação para iniciação científica. São Paulo, SP: Atlas. [ Links ]

Silva, E. F. G., & Santos, S. E. B. (2014). Paternidade adotiva: Conjugando afetos consentidos. Revista da Abordagem Gestalt, 20(2),161-167. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/rag/v20n2/v20n2a03.pdf [ Links ]

Silva, M. C. P. (2011). A construção da parentalidade em mães adolescentes: Um modelo de prevenção e intervenção. Curitiba, PR: Honoris Causa. [ Links ]

Sonego, J. C., & Lopes, R. C. S. (2009). A experiência da maternidade em mães adotiva. Aletheia, 29, 16-26. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/aletheia/n29/n29a03.pdf [ Links ]

Souza, D. B. L., & Ferreira, M. C. (2005). Auto-estima pessoal e coletiva em mães e não-mães. Psicologia em Estudo, 10(1),19-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722005000100004 [ Links ]

Souza, M. T., Silva, M. D., & Carvalho, R. (2010). Revisão integrativa: O que é e como fazer. Einstein, 8(1),102-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082010rw1134 [ Links ]

Statute of Children and Adolescents. (1990, September 27). Lei nº 8. 069, de 13 de julho de 1990. Dispõem sobre o Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União. Retrieved from http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccvil_03/leis/L8069.htm [ Links ]

Tardin, E. B., Barbosa, M. T., & Leal, P. C. A. (2015). Mulher, trabalho e a conquista do espaço público: Reflexões sobre a evolução feminina no Brasil. Revista Transformar, 7, 119-135. Retrieved from http://www.fsj.edu.br/transformar/index.php/transformar/article/view/34/31 [ Links ]

Tarnovski, F. L. (2012). Devenirpèrehomosexuelen France: laconstructionsocialedudésir d'enfant. Etnográfica, 16(2),247-267. Retrieved from http://etnografica.revues.org/1487#authors [ Links ]

Trindade, Z. A., & Enumo, S. R. F. (2002). Triste e incompleta: Uma visão feminina da mulher infértil. Psicologia USP, 13(2),151-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-65642002000200010 [ Links ]

Uziel, A. P. (2007). Homossexualidade e adoção. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Garamond. [ Links ]

Vitule, C., Couto, M. T., & Machin, R. (2015). Casais de mesmo sexo: Um olhar sobre o uso de tecnologias reprodutivas. Interface, 19(55),1169-1180. doi: 10.1590/1807-57622014.0401 [ Links ]

Weber, L. N. D. (2010). Pais e filhos por adoção no Brasil (9th ed.). Curitiba, PR: Juruá [ Links ].

Zanardo, L. B., Teixeira-Filho, F. S., & Ribeiro, E. M. C. (2014). Os Efeitos da Matriz Bioparental nos processos de adoção de crianças e adolescentes. Revista Psicologia UNESP, 13(1),60-85. Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/revpsico/v13n1/a06.pdf [ Links ]

Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Juliana Machado Ruiz

Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, Instituto de Educação, Letras, Artes, Ciências Humanas e Sociais

Avenida Getúlio Guarita, Nossa Senhora da Abadia

Uberaba - MG, Brazil 38025440

Phone: (34) 3318-5944

E-mail: julianamruiz@hotmail.com, camilaappborges@gmail.com, huebmartha@gmail.com, rafaeldetilio.uftm@gmail.com and fabioscorsolini@gmail.com

Received: 17/01/2018

1st revision: 19/03/2018

2nd revision: 13/04/2018

Accepted: 15/04/2018

Support: Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG); Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Authors' Contributions

Substantial contribution in the concept and design of the study: Juliana Machado Ruiz e Camila Aparecida Peres Borges.

Contribution to data collection: Juliana Machado Ruiz e Camila Aparecida Peres Borges.

Contribution to data analysis and inter-pretation: Juliana Machado Ruiz, Camila Aparecida Peres Borges, Martha Franco Diniz Hueb, Rafael De Tilio e Fábio Scorsolini-Comin.

Contribution to manuscript preparation: Juliana Machado Ruiz, Camila Aparecida Peres Borges, Martha Franco Diniz Hueb, Rafael De Tilio e Fábio Scorsolini-Comin.

Contribution to critical revision, adding intelectual content: Juliana Machado Ruiz, Camila Aparecida Peres Borges, Martha Franco Diniz Hueb, Rafael De Tilio e Fábio Scorsolini-Comin

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the publication of this manuscript.