Psicologia Clínica

ISSN 0103-5665 ISSN 1980-5438

Psicol. clin. vol.34 no.2 Rio de Janeiro maio/ago. 2022

https://doi.org/10.33208/PC1980-5438v0034n02A01

THEMATIC SECTION – REVIEW, ASSESSMENT AND DEVELOPMENT, THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL, IN CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

Qualification of psychologists for the care of sexual and gender minorities

Formação de psicólogos para o atendimento de minorias sexuais e de gênero

Formación de psicólogos para la atención de minorías sexuales y de género

Samir Vidal MussiI; Fani Eta Korn MalerbiII

IMestre em Análise do Comportamento pela Universidade Estadual de Londrina (UEL). Doutorando na Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. email: samirmussi@gmail.com

IIDoutora em Psicologia (Psicologia Experimental) pela Universidade de São Paulo (USP). Professora titular da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. email: fanimalerbi@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Stressors stemming from the prejudice against the LGBTQIAP+ population have been associated with psychological disorders which lead these people to seek healthcare services. However, the qualification of professionals to accommodate this population appears to be deficient. Affirmative therapy has been considered a major strategy which can be deployed by healthcare professionals in the care of this public. This work was aimed at reviewing inquiries evaluating affirmative therapy trainings. Six studies were selected, then assessed regarding subjects' characteristics, employed measures, contingencies of reinforcement involved in this type of therapy, strategies adopted in the training, self-assessment of the therapist regarding their own sexual prejudices, topics addressed in the course, limitations of the studies, and suggestions by the authors. The results indicated that the teaching of affirmative therapy must involve the identification of aversive contingencies present in the environment where the LGBTQIAP+ population lives, the programming of reinforcement contingencies which allow people to disclose themselves as belonging to this population, and the validation of this population's sexual orientation and gender identity as healthy. In these trainings, it is also suggested that therapists encourage LGBTQIAP+ people to seek support groups. Another important issue identified in the analyzed trainings is the instruction for the therapist to continually observe their own responses to LGBTQIAP+ people, in order to avoid reproducing LGBTphobia in their service.

Keywords: sexual and gender minorities; affirmative therapy; LGBTQIAP+; qualification of psychologists; behavior analysis.

RESUMO

Os estressores advindos do preconceito contra a população LGBTQIAP+ têm sido associados a transtornos psicológicos que levam essas pessoas a procurar serviços de saúde. Todavia, constata-se que a formação dos profissionais para atender a esta população é deficiente. A terapia afirmativa tem sido considerada uma estratégia importante que pode ser empregada por profissionais de saúde para atender a esse público. Este trabalho teve o objetivo de revisar investigações que avaliaram treinamentos em terapia afirmativa. Foram selecionados seis estudos, que foram analisados quanto às características dos participantes, às medidas empregadas, às contingências de reforço envolvidas nesse tipo de terapia, às estratégias empregadas no treinamento, à autoanálise do terapeuta quanto aos seus próprios preconceitos sexuais, aos temas abordados no curso, às limitações dos estudos e às sugestões dos autores. Os resultados indicaram que o ensino da terapia afirmativa deve envolver a identificação das contingências aversivas presentes no ambiente onde vive a população LGBTQIAP+, a programação de contingências de reforço que possibilitem que as pessoas se declarem pertencentes a essa população e a validação da orientação sexual e da identidade de gênero dessa população como saudável. Nesses treinamentos também se sugere aos terapeutas que incentivem as pessoas LGBTQIAP+ a buscarem grupos de apoio. Outra questão importante identificada nos treinamentos analisados é a instrução para que o terapeuta observe constantemente suas próprias respostas em relação às pessoas LGBTQIAP+, de modo a não reproduzir a LGBTfobia nos atendimentos.

Palavras-chave: minorias sexuais e de gênero; terapia afirmativa; LGBTQIAP+; formação de psicólogos; análise do comportamento.

RESUMEN

Los factores estresantes derivados del prejuicio contra la población LGBTQIAP+ se han asociado con trastornos psicológicos que llevan estas personas a buscar servicios de salud. Sin embargo, parece que la formación de profesionales para atender esta población es deficiente. La terapia afirmativa se ha considerado una estrategia importante que pueden utilizar los profesionales de la salud para atender este público. Este trabajo tuvo como objetivo revisar investigaciones que evaluaron el entrenamiento en terapia afirmativa. Se seleccionaron y luego analizaron seis estudios respecto a las características de los participantes, las medidas utilizadas, las contingencias de refuerzo involucradas en este tipo de terapia, las estrategias utilizadas en el entrenamiento, el autoanálisis del terapeuta de sus propios prejuicios sexuales, el contenido conceptual enseñado, las limitaciones de las investigaciones y las sugerencias de los autores. Los resultados indicaron que la enseñanza de la terapia afirmativa debe involucrar la identificación de contingencias aversivas presentes en el entorno donde vive la población LGBTQIAP+, la programación de contingencias de refuerzo que permitan a las personas reconocerse como pertenecientes a esta población y la validación de la orientación sexual e identidad de género de esta población como saludable. En estos entrenamientos, también se sugiere a los terapeutas que alienten a las personas LGBTQIAP+ a buscar grupos de apoyo. Otro tema importante identificado en las capacitaciones analizadas es la instrucción al terapeuta de observar constantemente sus propias respuestas en relación con las personas LGBTQIAP+, para no reproducir la LGBTfobia en las consultas.

Palabras clave: minorías sexuales y de género; terapia afirmativa; LGBTQIAP+; formación de psicólogos; análisis del comportamiento.

Introduction

In Western culture, people belonging to sexual and gender minorities (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and travesti, queer, intersex, asexual, pansexual, and others: LGBTQIAP+)1 are often isolated, receive limited social support, and experience violence (Balsam & Hughes, 2013). This adverse situation has been associated with disorders such as emotional dysregulation, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Mustanski et al., 2014). Minority stress theory is an attempt to understand the high prevalence of mental health problems found in minorities (Meyer, 2003).

Minority stress is faced by the LGBTQIAP+ population in a context of a hetero- and cisnormative culture and leads to a higher demand for health care services (Cohen et al., 2021; Doyle & Molix, 2016). Although many seek treatment, prejudice and lack of knowledge displayed by health professionals have been reported as major obstacles encountered by LGBTQIAP+ people when accessing these services (Cronin, 2017; Pepping et al., 2017; Pepping et al., 2018). Some authors point out that health professionals frequently tell LGBTQIAP+ people that it would be easier for them if they acted as heterosexual or cisgender people (Pepping et al., 2018; Shelton & Delgado-Romero, 2011).

Some studies assessing psychological therapy training have found that undergraduate programs do not address minority stress concepts, nor do they provide the skills needed for serving the LGBTQIAP+ population, which can be considered a shortcoming in professional training (Cronin, 2017; Henke et al., 2009; McGeorge et al., 2015; Rock et al., 2010). Other studies have showed that the peculiar features of LGBTQIAP+ couples are not addressed in graduate programs focusing on couple and family therapy training (Godfrey et al., 2006; Rock et al., 2010). Data on psychology and psychiatry training demonstrate that students are not prepared to work with sexual and gender minorities (Rock et al., 2010; Savage et al., 2004).

A Brazilian study conducted by Mizael et al. (2019) investigated the conceptions of sexual and gender diversity demonstrated by undergraduate psychology students interested in gender and sexuality issues, as well as their knowledge of Brazilian Federal Council of Psychology statements regarding homosexuality and transgender identity. The authors administered a questionnaire to 82 Brazilian college students. The results showed that most conceptions of homosexuality were consistent with the understandings of the entities responsible for regulating and supervising psychological professional practice, i.e., homosexuality is not a disease, LGBTphobia must be opposed, approaches that pathologize sexual orientation and gender identity are banned, participation in events that promote a "cure for homosexuality" is prohibited, and spreading LGBTphobia in the media is unacceptable. However, when it comes to transgender identities, the data revealed a lack of knowledge and conceptions different from the established ones regarding currently used definitions, in addition to pathologization of such identities.

To guide psychologists working with sexual and gender minorities, the American Psychological Association (APA) has developed guidelines comprising six categories. According to these guidelines, psychologists should (1) consider homosexuality and bisexuality healthy and identify the effects of prejudice on sexual and gender minorities; (2) investigate aversive control over the behaviors of this population in their families of origin and understand loving relationships of LGBTQIAP+ people as healthy; (3) investigate the impact of LGBTphobia associated with other forms of prejudice, such as racism and ageism; (4) identify the impact of prejudice on the work environment of this population; (5) seek training and specific knowledge on sexual and gender minorities; and (6) commit to the accuracy of information obtained in LGBTQIAP+ research and spread prejudice-free information (APA, 2012).

With the intent of improving psychological assistance for sexual and gender minorities, some authors have developed an intervention named affirmative therapy (Budge & Moradi, 2018; Heck, 2017; Johnson, 2012; McGeorge & Carlson, 2011; Moradi & Budge, 2018; O'Shaughnessy & Speir, 2018). Affirmative therapy is defined as "the integration of knowledge and awareness by the therapist of the unique cultural aspects of the development of LGBT individuals, the therapist's own self-knowledge, and the translation of this knowledge and awareness into effective and helpful therapy skills at all stages of the therapeutic process" (Perez, 2007, p. 408).

According to Pepping et al. (2018), affirmative therapy must be conducted by mental health professionals who view the LGBTQIAP+ spectrum of sexual orientations and gender identities as healthy, regardless of their theoretical approach. Recently, several publications have addressed affirmative therapy (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012; McGeorge et al., 2015; Craig et al., 2021; Pepping et al., 2018; Rock et al., 2010).

The purpose of this paper was to review studies assessing affirmative therapy training. The training programs were described and evaluated for their effectiveness in qualifying mental health professionals to serve the LGBTQIAP+ population.

Method

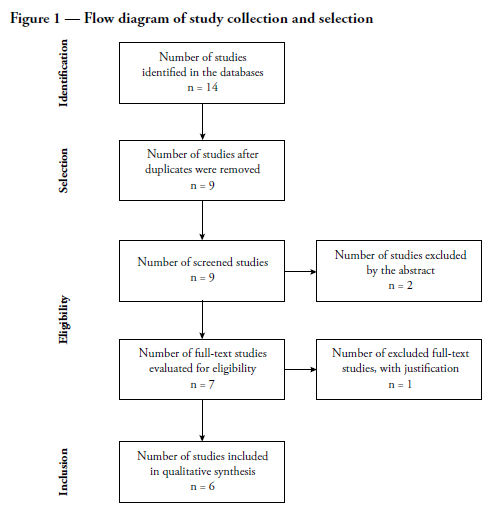

The CAPES portal and the PubMed, LILACS, PsycINFO, SciELO, and MEDLINE databases were searched for articles twice on March 13, 2021, with the Boolean operators "OR" and "AND". The first set of search terms were "affirmative therapy" OR "affirmative psychotherapy" AND "training", while the second set used the equivalent Portuguese terms, "terapia afirmativa" OR "terapia afirmativa" AND "treinamento". First, the abstracts of the articles found were screened. Articles with no descriptions of training programs, assessments of affirmative therapy training, or interventions for LGBTQIAP+ people were excluded. After full-text screening, one study was excluded because it concerned a training course for LGBTQIAP+ military personnel. Two studies cited by the selected articles were also analyzed and described only in the section Topics covered during training, because they are detailed descriptions of interventions (Craig & Austin, 2016; McGeorge & Carlson, 2011). These studies were not included in other sections because they did not assess any affirmative therapy training program. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of selection of the studies reviewed in this paper.

The six articles assessing affirmative therapy training programs were analyzed during full-text screening and categorized according to participants' characteristics, measures employed, training approaches and an analysis of contingencies of reinforcement involved, study limitations, and author suggestions. In the two studies describing training programs in detail, the teacher's antecedent stimuli, the students' responses, and the consequent stimuli were identified. Regarding topics covered during training, in addition to the six studies selected in the systematic review, the two studies describing affirmative therapy training were included.

Results and discussion

Of the six studies selected for this review, two described training programs provided and assessed by the authors themselves (Craig et al., 2021; Pepping et al., 2018), while the others assessed affirmative therapy training in couple and family therapy courses provided by educational institutions (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012; McGeorge et al., 2015; Rock et al., 2010), all of them conducted outside Brazil.

Participants' characteristics

Table 1 shows the number of professionals trained in each study, as well as their age, length of professional experience, gender, sexual orientation, and skin color.

As seen in Table 1, two authors (McGeorge and Carlson) were involved in the four studies assessing couple and family therapy courses. They are both faculty members at the Human Development and Family Science Department, North Dakota State University, United States, and their research is frequently cited by studies addressing sexual and gender minorities (McGeorge et al., 2015).

The number of participants in the six studies analyzed ranged from 96 to 248. Table 1 shows that participants' age and length of experience varied across studies. Carlson and McGeorge (2012), however, did not report length of experience of the professionals undergoing training. In five studies, most participants were female and heterosexual. Moreover, in the three studies that mentioned skin color, the majority were White.

A single study (Pepping et al., 2018) described distribution of participants by religious belief, showing that only 40% had no beliefs. Therapists' religious beliefs have been associated with a lower likelihood of affirmative interventions (Pepping et al., 2018) and, therefore, require more attention from authors.

Measures used during training

All reviewed studies used measurement tools that were based on verbal behavior of the students or the teacher. These tools are described below, with examples of questions.

(1) Client Satisfaction Questionnaire - CSQ (Larsen et al., 1979)

Used by Craig et al. (2021), the CSQ was administered to students in order to assess quality of and satisfaction with the training received. Some examples of CSQ questions include, "How would you rate the quality of service you received?"; "How satisfied are you with the amount of help you received?"; "Have the services you received helped you to deal more effectively with your problems?".

(2) Affirmative CBT Facilitator Competence Scale - ACCS (Craig et al., 2021)

This scale, also used by Craig et al. (2021), was administered to students in order to assess their opinions about whether training was useful, whether the program identified the impact of prejudice on the behavior of LGBTQIAP+ people, and whether the proposed activities facilitated the learning process. Some examples of ACCS statements include, "This workshop provided me with clinical tools that I can integrate into my practice"; "The workshop has helped me better understand how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are impacted by discrimination against LGBTQ+ populations"; "The training was a good mix of experiential and didactic exercises"; "I was given a chance to participate and discuss information"; "Overall, I am satisfied with the training".

(3) Affirmative Training Inventory - Faculty Version - ATI-F (Carlson et al., 2013)

Unlike the two previous tools, the ATI-F, created by Carlson et al. (2013) and used by Carlson and McGeorge (2012) and by McGeorge et al. (2015), aims to assess training from a teacher's perspective, with questions about whether the course addressed: the experiences of the LGBTQIAP+ population; the influence of biases on the behavior of this population; the heterosexual privileges that exist in our culture; the support that should be provided by the therapist when people identify as LGBTQIAP+ and whether students were encouraged to report their own biases. This tool also includes items addressing whether affirmative interventions were taught, whether LGBTQIAP+ students were recruited for the course, whether the course environment was free from aversive stimuli for LGBTQIAP+ students, and whether the teacher had appropriate experience and training to teach affirmative therapy. Some examples of ATI-F statements include, "In my family therapy courses, I specifically include content related to LGBTQIAP+ experiences"; "I teach my students about the influence of heterosexual bias (i.e., the act of conceptualizing human experiences in heterosexual terms, thereby marginalizing LGBTQIAP+ experiences and relationships) on the therapy process"; "I encourage my family therapy students to explore their own heterosexual biases (i.e., the act of conceptualizing human experience in heterosexual terms, thereby marginalizing the experiences and relationships of LGBTQIAP+ individuals)"; "I feel competent in my ability to train students to be affirmative in their clinical work with the LGBTQIAP+ population".

(4) Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Affirmative Counseling Self-Efficacy Inventory - LGB-CSI (Dillon & Worthington, 2003)

The LGB-CSI, developed by Dillon and Worthington (2003) and used by Pepping et al. (2018), aims to assess whether students started seeing LGBTQIAP+ status as healthy after training and are now able to: create an environment free from aversive stimuli in therapy sessions; describe their own biases; help their clients to describe emotions and thoughts related to sexual orientation and gender identity; teach strategies for coping with bias, advising the LGBTQIAP+ population to seek social, legal, and emotional support groups; and assess the client's psychiatric disorders. Some examples of LGB-CSI statements include, "I applied specific knowledge about the behaviors of LGBTQIAP+ people in my clinical practice"; "I helped a client identify sources of internalized LGBTphobia"; "I assisted LGBTQIAP+ clients to develop effective strategies to deal with heterosexism and LGBTphobia"; "I selected affirmative counseling techniques and interventions when working with LGBTQIAP+ clients"; "I referred LGBTQIAP+ clients to affirmative legal and social supports"; "I recognized when my own heterosexist biases may suggest the need to refer an LGBTQIAP+ client to another therapist".

(5) Revised Sexual Orientation Counselor Competence Scale - R-SOCCS (Bidell, 2005)

The R-SOCCS was developed by Bidell (2005) and was responded to by students after couple and family therapy training in courses described by Carlson and McGeorge (2012), McGeorge et al. (2015), and Rock et al. (2010). The R-SOCCS aims to check whether students received any training and supervision for attending LGBTQIAP+ people in these courses, whether they felt qualified for this service, and whether they were able to describe their biases towards the LGBTQIAP+ population. This tool also examines whether students performed role-play activities during the course and whether the behaviors of LGBTQIAP+ people were seen as healthy or as something that should be modified. Some examples of R-SOCCS statements include, "I have received adequate clinical training and supervision to counsel LGBTQIAP+ clients"; "At this point in my professional development, I feel competent, skilled, and qualified to counsel LGBTQIAP+ clients"; "I feel that sexual orientation differences between therapist and client may pose an initial barrier to effective counseling of LGBTQIAP+ individuals"; "I have done counseling role-play as either the client or therapist involving an LGBTQIAP+ issue"; "The lifestyle of an LGBTQIAP+ person is healthy"; "I believe that LGBTQIAP+ people must be discreet about their sexual orientation"; "It would be best if my clients viewed a heterosexual and cisgender lifestyle as ideal".

(6) Modern Homonegativity Scale - MHS (Morrison & Morrison, 2003)

This scale was developed by Morrison and Morrison (2003) and used by Pepping et al. (2018) to assess students' prejudice towards the LGBTQIAP+ population. Some examples of MHS statements include, "Many LGBTQIAP+ people use their sexual orientation so that they can obtain special privileges"; "The media devote far too much attention to the LGBTQIAP+ topic"; "Celebrations such as 'LGBTQIAP+ Pride Day' are ridiculous, because they assume that an individual's sexual orientation should constitute a source of pride"; "LGBTQIAP+ people should not have the same rights as other people"; "LGBTQIAP+ people should not be allowed to work with children"; "LGBTQIAP+ people are immoral".

In all reviewed studies, assessments of affirmative therapy training or therapist's skills after training involved student and/or teacher participation. The most used tools were the R-SOCCS (three studies) and the ATI-F (two studies). There are several similarities among the tools used, such as the respondents' assessment of the impact of specific aversive contingencies on the behaviors of LGBTQIAP+ people, the need for interventions to take place in an environment free from aversive stimuli, the need to support the attitudes of the LGBTQIAP+ population (clients and therapists) towards assuming their gender identity and sexual orientation, the recognition that these identities and orientations are healthy, and the importance of specific therapist training for working with the LGBTQIAP+ population. These aspects are directly related to the skills that should be considered in affirmative therapy training.

Training approaches

For an analysis of the training approaches reported in the reviewed studies, the descriptions provided in the two studies in which affirmative therapy courses were taught by the authors themselves were used (Craig et al., 2021; Pepping et al., 2018), as well as the implications for clinical training indicated by studies assessing existing couple and family therapy courses (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012; McGeorge et al., 2015; Rock et al., 2010). Two additional studies cited in the reviewed articles were also used, because they described important aspects to be considered in training (Craig & Austin, 2016; McGeorge & Carlson, 2011).

For greater clarity about how psychotherapist training for serving the LGBTQIAP+ population was conducted, the descriptions were organized according to the strategies used and the instructions for therapist self-awareness of sexual prejudice.

Strategies used during training

Only the two studies in which training was provided and assessed by the authors themselves described the strategies used during training (Craig et al., 2021; Pepping et al., 2018). The remaining four studies assessing affirmative therapy training in couple or family therapy courses, taught at educational institutions, did not describe the strategies used (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012; McGeorge et al., 2015; Rock et al., 2010).

The training approach reported by Pepping et al. (2018) consisted of a 7.5-hour workshop over one day. The following strategies were employed: didactic presentation of affirmative therapy topics; use of videos to illustrate situations related to the experiences of LGBTQIAP+ people; group discussion; and reflection activities with questions and answers. Craig et al. (2021) conducted an intensive 14-hour training workshop over two days, with eight modules, video instructions, standardized manuals, and PowerPoint slides. In both studies, strategies such as simulation of real-life experiences, observation of sessions with psychotherapists who should act as role models, and behavioral rehearsals were used to practice affirmative interventions, with feedback provided regarding the behaviors displayed by students that could differentially reinforce appropriate student responses.

From a behavioral perspective, slides and videos were used by teachers to offer students instructions and role models. Behavioral rehearsals about how to conduct affirmative interventions enabled students to exhibit behaviors in a situation where the teacher could provide differential reinforcement for appropriate responses. Students were also instructed to apply the interventions in a behavioral rehearsal situation that allowed the teacher to follow up with supportive words the students' responses when they stated that their clients' sexual orientation and gender identity were healthy.

Therapist self-awareness of sexual prejudice

In the training description provided by Pepping et al. (2018), it was possible to identify that the teacher provided instructions so that students identified their overt or covert sexual prejudices.

A description of the rules controlling the therapists' own behaviors and biases towards sexual and gender minority individuals and their relationships was one of the training goals described by Carlson and McGeorge (2012), McGeorge and Carlson (2011), McGeorge et al. (2015), and Rock et al. (2010). In the training approach reported by Carlson e McGeorge (2012), students were instructed to describe their own sexual prejudices.

McGeorge and Carlson (2011) suggested some questions designed to be responded by psychologists willing to work with sexual and gender minorities. The questions cover a description of the therapists' own behaviors towards sexuality (their own and others'), the hetero- and cisnormative rules that are likely to control these behaviors, the existing hetero- and cisgender privileges in society, and hypotheses about how heterosexual orientation and cisgender identity develop in most cases. Examples of these questions include, What did my family of origin teach me about LGBTQIAP+ people? What values were communicated? If none, what did that silence communicate? What are my initial thoughts or feelings about children who are raised by LGBTQIAP+ parents? What are my experiences using or hearing phrases like "that's so gay" or "fag" during my growing-up years and today? What values are associated with these terms? When I first meet someone, how often do I assume that he or she is cisgender or heterosexual? What values and beliefs inform this assumption? As a child, how were you encouraged to play according to heterosexual or cisgender norms? Have you ever had to question your heterosexuality or cisgenderness? Have you ever had to defend your heterosexuality or cisgenderness in order to gain acceptance among your peers or colleagues? Have you ever worried that you might lose your job because of your heterosexuality or cisgenderness? Have you ever worried that your therapist might try to change your heterosexuality or cisgenderness? Have you worried that you might be "outed" as a heterosexual or cisgender person? Have you ever feared that you would be physically harmed based solely on your heterosexuality or cisgenderness? How does your identification as a heterosexual or cisgender person influence the way you do therapy with all of your clients (regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity)?

Notably, although these studies highlighted the importance of therapists being able to describe their prejudices, privileges, and expressions of their own sexuality, they did not report whether there would be consequences for the responses. They only mentioned the importance of therapists frequently asking themselves these questions.

Topics covered during training

Although the reviewed studies did not describe in detail the topics covered during training, eight categories were identified.

(1) LGBTQIAP+ terminology

In the study reported by Pepping et al. (2018), the teacher introduced the meanings of terms related to the LGBTQIAP+ movement, such as transgender, pansexual, intersex, and queer. Carlson and McGeorge (2012) made several recommendations that future studies of psychotherapist training include specific discussions of heterosexism, heterosexual privilege, and heterosexual prejudice.

(2) Minority stress

In the training approaches described by Pepping et al. (2018) and by Rock et al. (2010), the teacher emphasized the concept of minority stress, which has been considered a consequence of factors such as isolation, lack of social support, and physical and sexual assault in a socially discriminated group such as the LGBTQIAP+ population. The different forms of aversive consequences towards the behaviors of the LGBTQIAP+ population (physical and verbal assault, punishment, isolation, conversion therapy), the context in which they occur (family, school, work, relationships), and their association with disorders (negative feelings about oneself, anxiety and depression, drug abuse) were addressed.

(3) "Coming out"

According to Pepping et al. (2018), the teacher suggested ways for therapists to reinforce, using supportive words, their clients' responses to having revealed their LGBTQIAP+ status, especially to family members.

(4) Internalized LGBTphobia

An analysis of the studies conducted by Pepping et al. (2018) and Rock et al. (2010) reveals that the teacher highlighted that people's feelings of discomfort regarding their own sexuality were developed in a context of aversive stimuli, such as those mentioned in the minority stress item, which was the environment where LGBTQIAP+ people were raised.

(5) Religious beliefs

As reported by Pepping et al. (2018), the teacher addressed the conflicts between religious beliefs and sexuality.

(6) Therapy with same-sex couples

In the training approach described by Pepping et al. (2018), the teacher highlighted the similarities and differences between heterosexual and same-sex couples, the influence of LGBTphobia on relationships, issues regarding disclosure of the relationship to other people, and what psychotherapeutic work with couples in open relationships should be like.

(7) Therapy with transgender clients

With regard to the transgender population, the training approach described by Pepping et al. (2018) also addressed the topics of gender dysphoria; coming out as transgender; and what gender transition is and the changes that are still needed in health care services to serve this population.

(8) Affirmation of sexual orientations and gender identities

In the studies conducted by Craig et al. (2021) and Rock et al. (2010), the importance of the therapist assuring the client that homosexual orientation and transgender identity are healthy was emphasized. In these training programs, students were instructed to verbally reinforce positive views during clinical assistance.

In summary, the concepts addressed in the training approaches described in the reviewed studies refer to the specific contingencies of reinforcement involved in the behaviors of LGBTQIAP+ people and to affirmative interventions that provide an environment free from aversive stimuli, in which the psychotherapist views different sexual orientations and gender identities as healthy and suggests that LGBTQIAP+ people be included in support groups.

Professionals who have been trained in working with sexual and gender minorities have listed the benefits of this experience, such as acquisition of a higher level of clinical competence (McGeorge et al., 2015; Rock et al., 2010), improved therapeutic knowledge and skills (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012; Pepping et al., 2018), and greater ability to provide unbiased mental health services (Austin & Craig, 2015). After undergoing affirmative therapy training, some professionals have also reported a decrease in their clients' negative feelings about themselves and a lower degree of social isolation (Austin & Craig, 2015).

The present review also found that although affirmative therapy training is considered important to satisfactorily deal with the problems faced by sexual and gender minorities seeking health care services, limited research to date has been devoted to describing and assessing courses whose aim is to develop affirmative therapeutic skills. Also, the interventions described seem to emphasize the antecedent stimuli and the responses expected from students, while neglecting an important aspect according to behavior analysis, which is reinforcing these responses so that they are maintained until natural reinforcers come into play.

Limitations reported in the studies

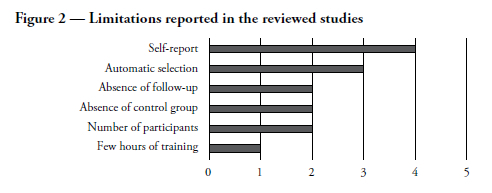

Several studies mentioned limitations in assessing training effectiveness. Figure 2 lists these limitations.

As shown in Figure 2, four studies (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012; Craig et al., 2021; McGeorge et al., 2015; Rock et al., 2010) identified participants' self-reporting as a limitation for training assessment. These studies suggested employing other measurement methods (video recording of the intervention and direct observation) to ensure greater reliability of results.

Three studies listed self-selection (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012; McGeorge et al., 2015; Rock et al., 2010) as a limitation, as study subjects volunteered to participate. It is known that nonprobabilistic samples may not adequately represent the population to which the research question is addressed. The student therapists in the different training courses analyzed may have specific characteristics that lead to a greater likelihood of having previously come into contact with issues addressed by the course or being more interested in the topic than other psychotherapist samples.

Two studies listed lack of a control group as a problem in ensuring that results were due to the training and not to other external variables (Pepping et al., 2018; Craig et al., 2021).

Although they worked with samples of 248 and 117 participants, respectively, Carlson and McGeorge (2012) and McGeorge et al. (2015) listed the number of participants as a problem, highlighting the need to recruit larger samples in future studies.

Another limitation listed by Pepping et al. (2018) was the small number of hours of training. The authors point out that seven hours of training are unlikely to promote a change in professional skills.

Suggested improvements

Seven suggestions for improving future studies aiming to assess affirmative therapy training were identified in the review.

(1) Express support for sexual and gender minorities when marketing the courses

Carlson and McGeorge (2012) suggested that graduate programs use materials supporting sexual and gender minorities in their marketing campaigns and teaching environments.

(2) Serve sexual and gender minorities

Providing students with the opportunity of serving sexual and gender minority patients was another important factor. Teaching programs should promote recruitment strategies for these clients (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012).

(3) Observe affirmative therapy and supervision sessions

Carlson and McGeorge (2012) also suggested that professionals willing to work with sexual and gender minorities observe affirmative therapy sessions and participate in supervision sessions focused on this population.

(4) Support and promote research (faculty)

Carlson and McGeorge (2012) suggested that faculty members support and promote student research on topics involving sexual and gender minorities.

(5) Participate in LGBTQIAP+ organizations

In two studies, the authors suggested that programs work together with sexual and gender minority organizations to promote events supporting this population, such as LGBTQIAP+ pride parade, "Coming Out" week, and LGBTQIAP+ conferences (Carlson & McGeorge, 2012; McGeorge et al., 2015).

(6) Investigate therapist religious influences

Pepping et al. (2018) called for future research to investigate the influence of therapist religious beliefs on affirmative therapy training.

(7) Educate through books, manuals, and journals

Carlson and McGeorge (2012) also suggested that courses indicate a bibliography of affirmative therapy. They believe that students should access journals publishing studies on sexual and gender minorities, and cited the Journal of GLBT Family Studies, the Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, the Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, and the Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling.

The authors of the reviewed studies emphasize the importance of professionals willing to attend to LGBTQIAP+ people to be in frequent contact with courses, research studies, and movements related to this population.

Training from a behavior analysis perspective

From a behavior analysis perspective, affirmative therapy training should be designed so that the therapist is able to analyze past and current contingencies of reinforcement likely to be involved in the behaviors of LGBTQIAP+ people. Achieving this goal requires identifying the responses frequently given by LGBTQIAP+ people as well as the antecedent and consequent stimuli associated with such responses. Examples of events that should be analyzed by therapists-in-training are reports of discomfort with homosexual desires (internalized homophobia), self-isolation, concealment of failure in activities, distorted assumptions, relationship/sexual desire difficulties, responses related to conditions such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder, punishment during childhood when exhibiting behaviors different from those expected for their biological sex, exclusion by the family, unfavorable comparisons with heterosexual people, teasing at school, and undergoing psychological therapy to cure homosexuality (Mussi & Malerbi, 2020).

Moreover, therapists-in-training should be instructed to: describe their own sexual prejudice and heterosexual privilege (if they are heterosexual); identify the ways in which they express their sexuality; follow up the responses of people who identify as LGBTQIAP+ with words of support and encouragement; emphasize positive characteristics; provide instructions for the expression of emotional states; suggest participation in support groups for the LGBTQIAP+ population; assess whether the consequences that followed the appropriate responses of LGBTQIAP+ people succeeded in making them stronger; and seek constant improvement by participating in continuing education activities such as courses, conferences, and events focused on respecting diversity.

Conclusion

This review showed that the measurement tools used in the studies focus on the skills that should be acquired by students so that they can make effective interventions in psychotherapy sessions with the LGBTQIAP+ population. These skills include assessing specific contingencies related to the behaviors of LGBTQIAP+ people, building a nonpunitive environment, supporting the behaviors exhibited by LGBTQIAP+ people when they disclose their gender identity and sexual orientation, recognizing that these identities and orientations are healthy, and understanding that there should be specific training for therapists serving this population.

Regarding the training approaches reported in the studies, the teachers were found to use instructions, provide role models, and employ differential reinforcement for student responses and behavioral rehearsals with the aim of developing affirmative skills. Additionally, the teacher asked questions as a way of helping students describe their own prejudices, privileges, and expressions of sexuality. In the reviewed training approaches, the students received instructions to suggest to LGBTQIAP+ people that they take part in support groups.

Importantly, the present review comprised a small number of studies (eight in total), the description of the training approach was not always complete, and some studies focused on couple and family therapy instead of affirmative therapy.

Additional studies should be conducted to evaluate training approaches for psychotherapists interested in working with LGBTQIAP+ people so that they can be incorporated by educational institutions in the preparation of professionals who will work with this population. Other recommendations are that future studies assess specific affirmative therapy courses, describe students' religious beliefs, and engage LGBTQIAP+ and non-White participants.

References

APA - American Psychological Association (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist, 67(1), 10-42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024659 [ Links ]

Austin, A.; Craig, S. L. (2015). Empirically supported interventions for sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 12(6), 567-578. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2014.884958 [ Links ]

Balsam, K.; Hughes, T. (2013). Sexual orientation, victimization, and hate crimes. In: C. J. Patterson; A. R. D'Augelli (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and sexual orientation, p. 267-280. O.U.P. [ Links ]

Bidell, M. P. (2005). The sexual orientation counselor competency scale: Assessing attitudes, skills, and knowledge of counselors working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44(4), 267-279. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb01755.x [ Links ]

Budge, S. L.; Moradi, B. (2018). Attending to gender in psychotherapy: Understanding and incorporating systems of power. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 2014-2027. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22686 [ Links ]

Carlson, T. S.; McGeorge, C. R. (2012). LGB affirmative training strategies for CFT faculty: Preparing heterossexual students to work with LGB clients. In: J. J. Bigner; J. L. Wetchler (Eds.), Handbook of LGBT-affirmative couple and family therapy, p. 395-408. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Carlson, T. S.; McGeorge, C. R.; Toomey, R. B. (2013). Establishing the validity of the affirmative training inventory: Assessing the relationship between lesbian, gay, and bisexual affirmative training and students' clinical competence. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 39(2), 209-222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00286.x [ Links ]

Cohen, J. M.; Norona, J. C.; Yadavia, J. E.; Borsari, B. (2021). Affirmative dialectical behavior therapy skills training with sexual minority veterans. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 28(1), 77-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.05.008 [ Links ]

Craig, S. L.; Austin, A. (2016). The AFFIRM open pilot feasibility study: A brief affirmative cognitive behavioral coping skills group intervention for sexual and gender minority youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 64, 136-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.02.022 [ Links ]

Craig, S. L.; Iacono, G.; Austin, A.; Eaton, A. D.; Pang, N.; Leung, V. W. Y.; Frey, C. J. (2021). The role of facilitator training in intervention delivery: Preparing clinicians to deliver AFFIRMative group cognitive behavioral therapy to sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33(1), 56-77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2020.1836704 [ Links ]

Cronin, T. J. (2017). Determinants of clinical outcomes in lesbian, gay, and bisexual Australians: The role of minority stress and barriers to help-seeking (unpublished masters dissertation). La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. [ Links ]

Dillon, F.; Worthington, R. L. (2003). The lesbian, gay and bisexual affirmative counseling self-efficacy inventory (LGB-CSI): Development, validation, and training implications. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(2), 235-251. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.235 [ Links ]

Doyle, D. M.; Molix, L. (2016). Minority stress and inflammatory mediators: Covering moderates associations between perceived discrimination and salivary interleukin-6 in gay men. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(5), 782-792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9784-0 [ Links ]

Godfrey, K.; Haddock, S. A.; Fischer, A.; Lund, L. (2006). Essential components of curricula for preparing therapists to work effectively with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients: A Delphi study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 32(4), 491-504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2006.tb01623.x [ Links ]

Heck, N. C. (2017). Group psychotherapy with transgender and gender nonconforming adults: Evidence-based practice applications. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(1), 157-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.010 [ Links ]

Henke, T.; Carlson, T. S.; McGeorge, C. R. (2009). Homophobia and clinical competency: An exploration of couple and family therapists' beliefs. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 8(4), 325-342. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332690903246101 [ Links ]

Johnson, S. D. (2012). Gay affirmative psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: Implications for contemporary psychotherapy research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 516-522. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01180.x [ Links ]

Larsen, D. L.; Attkisson, C. C.; Hargreaves, W. A.; Nguyen, T. D. (1979). Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2(3), 197-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [ Links ]

McGeorge, C.; Carlson, T. S. (2011). Deconstructing heterosexism: Becoming an LGB affirmative heterosexual couple and family therapist. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 37(1), 14-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00149.x [ Links ]

McGeorge, C. R.; Carlson, T. S.; Toomey, R. B. (2015). Assessing lesbian, gay, and bisexual affirmative training in couple and family therapy: Establishing the validity of the faculty version of the affirmative training inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 41(1), 57-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12054 [ Links ]

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [ Links ]

Mizael, T. M.; Gomes, A. R.; Marola, P. P. (2019). Conhecimentos de estudantes de psicologia sobre normas de atuação com indivíduos LGBTs. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 39, e182761. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703003182761 [ Links ]

Moradi, B.; Budge, S. L. (2018). Engaging in LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies with all clients: Defining themes and practices. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 2028-2042. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22687 [ Links ]

Morrison, M. A.; Morrison, T. G. (2003). Development and validation of a scale measuring modern prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women. Journal of Homosexuality, 43(2), 15-37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v43n02_02 [ Links ]

Mussi, S. V.; Malerbi, F. E. K. (2020). Revisão de estudos que empregaram intervenções afirmativas para LGBTQI+ sob uma perspectiva analítico-comportamental. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.31505/rbtcc.v22i1.1438 [ Links ]

Mustanski, B.; Andrews, R.; Herrick, A.; Stall, R.; Schnarrs, P. W. (2014). A syndemic of psychosocial health disparities and associations with risk for attempting suicide among young sexual minority men. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 287-294. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301744 [ Links ]

O'Shaughnessy, T.; Speir, Z. (2018). The state of LGBQ affirmative therapy clinical research: A mixed-methods systematic synthesis. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(1), 82-98. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000259 [ Links ]

Pepping, C. A.; Lyons, A.; McNair, R.; Kirby, J. N.; Petrocchi, N.; Gilbert, P. (2017). A tailored compassion-focused therapy program for sexual minority young adults with depressive symptomatology: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychology, 5(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-017-0175-2 [ Links ]

Pepping, C. A.; Lyons, A.; Morris, E. M. J. (2018). Affirmative LGBT psychotherapy: Outcomes of a therapist training protocol. Psychotherapy, 55(1), 52-62. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000149 [ Links ]

Perez, R. M. (2007). The "boring" state of research and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients: Revisiting Barón (1991). In: K. J. Bieschke; R. M. Perez; K. A. DeBord (Eds.), Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients (2nd ed.), p. 399-418. Washington: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Rock, M.; Carlson, T. S.; McGeorge, C. R. (2010). Does affirmative training matter? Assessing CFT students' beliefs about sexual orientation and their level of affirmative training. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36(2), 171-184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00172.x [ Links ]

Savage, T. A.; Prout, H. T.; Chard, K. M. (2004). School psychology and issues of sexual orientation: Attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge. Psychology in the Schools, 41(2), 201-210. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10122 [ Links ]

Shelton, K.; Delgado-Romero, E. A. (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: The experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer clients in psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(2), 210-221. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022251 [ Links ]

Recebido em 11 de novembro de 2021

Aceito para publicação em 01 de maio de 2022

Este trabalho teve financiamento da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

1 Lesbian women and gay men are those who feel affective/sexual attraction to people of the same gender. Bisexuals are those who feel affective/sexual attraction to people of both male and female genders. Transgender people are those who do not identify with the gender they were assigned at birth. Travestis are also transgender people, but they constitute a third gender in the Brazilian context. Queer people are those who move between notions of gender. Intersex is the denomination for people with biological combinations and body development (chromosomes, genitals, hormones) that do not fit the binary norm (male or female). Asexuals are those who are not sexually attracted to other people, regardless of gender, or who do not see human sexual relationships as a priority. Pansexuals are those who are attracted to other people, regardless of gender. The + sign indicates the inclusion of other sexuality and gender variations.