Temas em Psicologia

ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.19 no.1 Ribeirão Preto jun. 2011

PRIMEIRA PARTE: ALGUMAS CONTRIBUIÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS

Social representations of female-male beauty and aesthetic surgery: a cross-cultural analysis

Annamaria Silvana de RosaI; Andrei HolmanII

ISapienza University, Rome, Italy

IIAlexandru I. Cuza University, Iasi, Romania

ABSTRACT

The aim of our research program is to investigate the socio-psychological interrelations between female/male beauty and aesthetic surgery in various social groups differentiated not only as a function of gender and education variables (female and male, young people with university training in Arts, Informatics and Sport) in three European countries (Italy, Spain and Romania), but also on the basis of psychological dimensions, like self-rated attractiveness, level of self involvement in the topic of aesthetic-plastic surgery, self-identification with salient cultural referents (like Beauty, Body, Culture, Nature, Soul). The Social Representation framework offers a wide range of heuristic and methodological tools especially called for by both the intimate and social nature of the topics under scrutiny. The study is part of a wider research design following an integrated multi-steps path from exploration to experimentation: 1) a study concerning content, structure, polarity, imagined and emotional dimensions of the Social Representations of female and male beauty and of aesthetic surgery; 2) a study focused on internet discussion forums on the topic of plastic/aesthetic surgery and aimed at investigating the construction of social discourse and negotiation among members of "virtual communities"; 3) a study employing the "body map" tool, an innovative tool with a graphical referent concerning the aesthetic surgery ranking of the various parts of the human body; 4) an experimental study focused on the generative activity of mental images and emotions in the S.R. of beauty and aesthetic surgery. The results here presented come from the multi-method research plan obtained in the first step through: a) the "Associative Network", using "female/male beauty" and "plastic/aesthetic surgery" as inductive words; b) the "Involvement level scale"; c) the "Self-attractiveness Scale"; d) the "Self Identification Conceptual Network". The data were explored by means of multi-step data analysis, including the lexical correspondence analysis. The results highlight cultural sharing and differences between groups, which give meaning to the interrelated objects of social representations in terms of contents, evaluations, emotional dimensions and referential system of values. They also show evidence of the influential variables in terms of gender, education, psychological dimensions (such as self-identification with cultural referents) and participants' countries with a different familiarization with the aesthetic surgery massive phenomenon. The cultural differences are also discussed with regard to the diffusion of aesthetic surgery in the three countries illustrated in the introductory section, presenting some epidemiological data.

Keywords: Female-Male Beauty, Aesthetic Surgery, Plastic Surgery, Body, Social Representations.

The aesthetic surgery: an impressively increasing phenomenon

According to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS1), a body which in 2010 represented 1925 practitioners in 87 countries2, Europe accounted for more than 33% of cosmetic procedures conducted in 2004, second only to all of the Americas.

According to 2002 statistics3 (one of the few available on the topic) of the diffusion of aesthetic surgery in the world, the three European countries of interest to the research to be presented here ranked as following: Spain in 3rd position, Italy in 24th, while Romania took the last place in the sample of countries listed - the 32nd. This objective description, in terms of aesthetic surgery procedures per capita, offers insight into the different degrees of diffusion and familiarization with the phenomenon. The Romanian situation is a special one, since before 1989 (during the communist regime), there were only around 30 plastic (reconstructive) surgeons, all working in state hospitals on victims of various illnesses or accidents. The first private aesthetic surgery clinic opened in 1994, and in the following year there were already 17 clinics, each with approximately 3 clients per week. The estimated market growth of the aesthetic surgery business is 18 - 20% / year, while the gender (imbalanced) distribution of its clients is similar to the one reported by the Western statistics: 80% women, and only 20% men.

However, if we look at the geographic trends emerging from the 2009 ISAPS Global Survey4 very recently released at the 20th Biennial Congress of ISAPS held on August 14-18 2010 in San Francisco (California, US), the new ranking of the top 25 countries and regions shows a new hierarchy. While the United States continues its dominance in the field, countries not always associated with plastic surgery are emerging as major centers: 1. United States 2. China 3. Brazil 4. India 5. Mexico 6. Japan 7. South Korea 8. Germany 9. Turkey 10. Spain 11. Argentina 12. Russia 13. Italy 14. France 15. Canada 16. Taiwan 17. United Kingdom 18. Colombia 19. Greece 20. Thailand 21. Australia 22. Venezuela 23. Saudi Arabia 24. Netherlands 25. Portugal.

The changing nature of the geographic trend supports the cultural importance of the phenomenon, influenced not only by socio-economic and mentality factors, but also by ideological and even religious belief systems, as shown for example in the article by Atiyeh, Kadry, Hayek and Musharafieh (2008) on aesthetic surgery and Islamic law perspective.

With its total number of 30,817 practicing board certified plastic surgeons estimated by ISAPS Global Survey in 2009 and the total number of surgical procedures (including among the top five: liposuction, breast augmentation, blepharoplasty, rhinoplasty, abdminoplasty) estimated to be 8,536,379 and the number of non surgical procedures (including among the top five: injections of toxins or neuromodulators - Botox, Dysport -, hyaluronic acid injections, laser hair removal, autologous fat injections, IP laser treatment) estimated at 8,759,187 (not including the surgical and non surgical procedures performed by non plastic surgeons), the phenomenon of aesthetic surgery involves by direct experience an impressive and progressively increasing number of specialists (surgeons) and ordinary people (patients) and activates contrasting opinions, attitudes and social representations among the world-wide population including opponents, indifferent people or potential future patients.

Research background

Our research program is the first cross-countries study, inspired by the Social Representations theory (de Rosa, 1994, 2012; Moscovici, 2000; Jodelet, 1984a), on the topic of beauty and aesthetic surgery, opening the route for other field studies of special cultural interest, for example comparing samples from Western and Asiatic countries. Currently an extension of our research program has been promoted in Brazil in cooperation with researchers from LACCOS/UFSC in Florianopolis.

In the absence of a specific literature on beauty and aesthetic surgery inspired by the same theoretical background, a fundamental reference in the Social Representation literature is the work of Denise Jodelet on the body in various cultures. Jodelet (1981, 1984b, 1994) states that Social Representations are a "privileged subject matter" regarding the body as a "product of techniques and representations". This perspective relies on and puts forward the dual nature of the body, as simultaneously social and private. While the individual, private side has been a focus of research for psychology mostly in terms of "body schema" or "body image", especially in relation to the associated psychopathological disorders (but also from an interdisciplinary and philosophical perspective (Tiemersma, 1989); the social dimension allows the departure of one's body experiences and practices from the strictly individual point of reference as a mediator of development (de Rosa & Carli, 1980) towards reliance upon various social representations, thus becoming a "social body". Jodelet's diachronic research, covering a 15-year period, highlights a certain progressive sense of liberation towards the body, in terms of the norms to be obeyed both in the intimate and the social realms. The reason for this increasing freedom from censorship in relation to one's body is its permanent inclusion in socio-cultural debates, especially by anti-establishment and innovatory movements.

While the individual-focused research mentioned above ignores the social insertion of the body and the cultural definitions of the norms through which one's body image (and, subsequently, beauty) is assessed, the opposite position is strongly advocated in socio-cultural studies, especially from the anthropological perspective. "Contemporary Western culture teaches us to think of the body as an object with a material reality that is physically observable, but anthropology shows that we perceive our bodies through a culturally constructed body image that shapes what we see and experience. As we negotiate social relationships, our sense of a body image develops, for the two are reciprocally related" (Sault, 1994, p. 1).

The general theme underlined in the literature developed under the impetus of the feminist movement is that the private or subjective body does not exist because it is entirely constructed and modified according to the criteria and rules of the oppressing group. Beauty is a key element in the gender unbalanced relationship, because women are trapped in the ideological gender-biased net that ensures the male domination, including expectations about feminine beauty standards. The "awakening" alarm that the feminist position rings targets women's "societal Stockholm syndrome" (Graham, 1994, p. 57), manifested through their tendency to identify the interests of their dominators as their own. The radical feminist approach describes one of the key components of what we might call the social representation of beauty as being a "feminine duty" at any cost. This cultural trap into which women are educated gives rise to a persistent culturally-induced body anxiety, which, in turn could be alleviated - at least temporarily - by the false solution of aesthetic surgery.

In this context, aesthetic surgery becomes an act of surrender to unattainable ideals of beauty. Moreover, given its medical and long term correlates, it detaches itself from the other beauty enhancing techniques as "the ultimate symbol of invasion of the human body for the sake of physical beauty" (Gimlin, 2000, p. 80). The aesthetic dimension of this intervention is left aside, since the social meaning and purpose of aesthetic surgery is mainly to make the stigmata of the inferior obvious.

This drastic feminist view on the topic calls in its support two kinds of arguments. Firstly, the gender distribution of the actors involved in the medical equation of aesthetic surgery has always been clearly unbalanced: while most of the surgeons are men, 80% of the patients are women. Secondly, we witness the increasing scientific and cultural "pathologisation" of non-standard looks; even the vast array of research in the individual dimension of the body marks this tendency, mostly by its focus on body weight and its pervasive reference to the threat of obesity. Another instance of non-standard appearance reframed as pathological is the invention in the medical literature of the term -"hypo-mastia" (Berry, 2007, p. 74), in order to describe the "pathology" of having small breasts.

Also, after its initial formulation as a gender issue, the "personal is political" (Hanisch, 1970) perspective on beauty extends to any kinds of social inequality which might compel the aesthetic enhancement of the dominated towards the norms put forth by the dominators. As such, the anchoring of aesthetic surgery in power relationships goes beyond gender, an idea illustrated by the multiplication of breast augmentation procedures on young Japanese women after World War II as a way to appeal to the American soldiers, or by the "ethnic plastic surgery" made obvious in the same period of time by the Italian and Jewish nose alterations undergone in order to fit American beauty norms. On a more general level, beauty plays a part even in the inter-racial realm, since the ideal proportions in plastic surgery handbooks (e.g. "Proportions of the Aesthetic Face") are based on a white, Western aesthetic of feminine beauty (Balsamo, 1997; see also "Opening" faces. The politics of cosmetic surgery and Asian American Women, by Kaw, 1994)5.

An alternative to the extremely critical perspective summarized so far is the liberal feminist perspective, which recognizes that aesthetic surgery has some rational use for women in order for them to cope with the vicissitudes of a male-dominated world. On the one hand, it offers them "a degree of control over their lives in circumstances where there are very few other opportunities for self-realization" (Negrin, 2002, p. 22). Thus, the social oppression discourse from which aesthetic surgery originates is taken for granted, no longer fought against; the new conflict is not between the two genders, but among the representatives of the weaker one, which could be labeled as "The survival of the prettiest", in a cultural scenario where cosmetic surgery is a tool for the eclipse of identity (Negrin, 2002).

On the other hand, aesthetic surgery is endorsed as a solution which could bring social inclusion for the person who undergoes it, alleviating the limitations deriving from the deviance of being ugly. This liberal feminist perspective builds on the idea of culturally induced anxiety in women, but, to emphasize its irrationality, it recognizes that the psychological pressures may be too much for some women to handle, and thus aesthetic surgery may be an easy way to become "normal". This drastic shift in attitude towards aesthetic surgery comes with a change in the criteria of beauty, from the extraneous norms imposed by the ruling men (in the former, radical view), to an in-group focus on normality as avoidance of ugliness.

The third feminist perspective we can identify brings a further increase in positivity towards aesthetic surgery, defining it as a way to express one's "true identity". The external referents - men - are deleted from the equation; there are no longer power relations to put pressure on women's decisions to undergo such procedures. The comparison which - in the case of a negative result - drives them towards aesthetic surgery is no longer between one's appearance and some external norms of beauty, but between one's own definition of self and the body, as a vehicle to convey one's true persona. This view marks the convergence of aesthetic surgery with all the body modification procedures (tattoos, piercings, etc.), leaving behind beauty as an interpersonal given and shifting it in the strictly individual sense. Thus, cosmetic surgery becomes simply another form of makeup; the effects on the body itself are overshadowed, in an obvious opposition to the radical feminist perspective, which goes so far as to define it as self-mutilation "by proxy" (Jeffreys, 2005, p. 149).

As such, the postmodern body is no longer a biological given whose organic integrity is inviolable; rather, it is "fragmented", a "text" which should express the messages which synthesize one's inner reality, reflecting one's personality or convictions. Most of the time, these messages have a social side to them, depicting certain positions as endorsed, or belongings as assumed; yet the aesthetic is only implicit, beauty as a purpose comes second to the goal of identity display.

This connection to the psychological dimension - and, more specifically, to psychological improvement, as in the second liberal view summarized above - was formulated by one of the first plastic aesthetic surgeons - Jacques Joseph (1896, cited in Frank, 1998, p. 105) - according to whom this kind of medical intervention represents "a means of repairing not the body but the psyche" (Frank, 1998, p. 105): in other words a technological solution to a psychological problem. One century later, in the modern medical literature on ideal proportions (e.g. on "the golden number"), one can identify the same idea of reparation, yet addressed strictly to the body: all humans have the potential to develop their body according to such proportions. Yet, this potential seldom achieves perfect results, since various factors interfere with one's harmonious development. The solution for this misfortune is aesthetic surgery, which promises to "deliver us from ugliness". This perspective, implicit in the evolutionist approaches on the topic, again detaches beauty from any social dynamics which could define its criteria or impose pressures to achieve it. Geometry is responsible for the aesthetic appeal, and aesthetic surgery is just an effective tool to restore the beauty promised in our genes.

A point shared by this view on beauty with the feminist discourse cited above is the uniformity and temporal stability of the criteria through which the body is evaluated, either by men - in the latter perspective - or by humans, in general - in the former. Even though history shows us that beauty criteria change drastically through time, this evolution is ignored, and the reason is the same: the strong reliance on the sexual dimension - indeed more or less stable throughout the ages. On the evolutionist view, this reliance takes the form of sexual selection which enforces a very strict set of physical evaluation checkpoints, which can ensure one's "mating quality". For the feminist side, male domination is achieved, among others, through sexual power, in terms of the man's right to choose the most gratifying sexual experience, and beauty is just a socially acceptable term to describe this feminine sexual quality.

Of course, fashion trends are temporally and culturally contextualized, as analysis of the advertisements based on top models or actresses in the last fifty years would make evident. However, if beauty standards and fashionable criteria can change over time and culture, "beauty" has undoubtedly a positive bias compared to "ugliness" everywhere and at any time.

"To say that beauty and ugliness are relative to the times and cultures (or even planets) does not mean that there has always tried to see them as defined in relation to a stable model" (Eco, 2007, p. 15).

The April 2011 issue (vol. 4, nº 4) of the journal Observer, published by the Association for Psychological Science APS, that dedicated its cover page to the topic In the mind of the beholder. The Science Behind Beauty starts the main article affirming "In this world, you're better off being good-looking. At all ages and in all walks of life, attractive people are judged more favorably, treated better, and cut more slack. Mothers give more affection to attractive babies. Teachers favor more attractive students and judge them as smarter. Attractive adults get paid more for their work and have better success in dating and mating. And juries are less likely to find attractive people guilty and recommend lighter punishments when they do" (p. 20)

A research field called "social aesthetics", which systematically investigates the social reactions to physical appearance, is the core of the 2008 Berry's book "The Power of Looks: Social Stratification of Physical Appearance". In its review, William Keenan (2009) affirms: "The normative order of beauty and ugliness is socially constructed, reinforced, sometimes challenged and, occasionally, changed. Positive and negative social reactions to 'looks', Berry tells us, come in many forms and are 'stratified' in multiple ways. Looks, especially 'good looks' that appeal to the public eye, are 'power', power to persuade, seduce, attract wealth and status associations, command recognition, and 'earn' vicarious 'rewards' from sexual to career to political favors. By contrast, 'uglies', the 'Others' incarnate, get a raw deal. The 'also rans', in the cruel, cold, cosmetisized game of beautification, attract stigma and discrimination, society's revenge on Nature's 'aesthetically challenged'. What might be called a global 'beauty caste' system is in the making, as the internationalization of the 'appearances are everything' industry with its glamour and style stereotypes invades and pervades cyberspace, roadside hoardings, 'looks product' commerce, and the 'world system' of 'human and non-human constructed beauty' (p. 103)."

"So here's the timeless message of psychological science: Be beautiful - or, as beautiful as you can. Smile and sleep and do whatever else you can do to make your face a reward. Among its other social benefits, attractiveness actually invites people to learn what you are made of, in other respects than just genetic fitness. According to a new study at the University of British Columbia (Lorenzo, Biesanz, & Human, 2010), attractive people are actually judged more accurately - at least, closer to a subject's own self-assessments - than are the less attractive, because it draws others to go beyond the initial impression. "People do judge a book by its cover," the researchers write, "but a beautiful cover prompts a closer reading." (APS Observer, April 2011, vol. 24, nº. 4: 22)

One of the aims of our research is empirically to test the stability/dynamics of beauty criteria, and the salience of the gender/education/national belonging dimensions in the social representations of the various groups interviewed.

The general assumption of our research program is that aesthetic surgery is at the same time a "social practice guided by" and "object of" Social Representation. The social practice of cosmetic surgery has always been strongly related to the social representations of beauty, and our research attempts to highlight the correlated dynamics of the social representations of masculine and feminine beauty and aesthetic surgery as social practice among various subject groups from different European countries.

Given the rapid growth of the aesthetic surgery industry (by 10% year on year), the increasing "popularization" or "democratization" of aesthetic surgery could be defined as "irreversible" (Flament, 1989), and thus should generate significant changes in the social representations of beauty. Given space limitations, the literature on aesthetic surgery presented above has been selected from a wider corpus of research characterized by different paradigmatic and methodological approaches, and in some cases also ideologically connoted field of studies, articulated with interrelated interdisciplinary fields focused on body and beauty.

This literature shows, on the one hand, that the various social dynamics in which beauty and aesthetic surgery are inserted have an ongoing evolution in contemporary society; on the other hand, a general shift in perspective on the body, from its traditional definition as an integer, whose defects should be assumed, to a "fragmented body" which allows modifications not only for the sake of the aesthetic norms, but also for the purpose of personal expression.

The ambiguous character of the body as "subjective construction" in the contemporary culture, where the body is object of an enormous symbolic investment, revealed by the obsession for the remade body, remodeled by the aesthetic surgery and body-building techniques, by the tattoos and by the piercing practices, has been discussed by Francisco Ortega (2008) in reference to multiple versions of the constructivism and disciplinary fields: the medical visualization of the "internal body" in the history of medicine (from the initial experiences of anatomical dissection, the advent of X-rays, up to today's bio-imaging techniques), the virtualization of the "transparent" body in the aesthetics and advertising, the ethical and psychological issues connected to the body's perception and experience. Extreme manifestations can be found in some performances of the body-art and in the carnal aesthetics (Papenburg & Zarzycka, 2011).

An emblematic case is the one of the French artist Orlan (the artistic name of Mireille Suzanne Francette Porte), who reinvented a career as an artist after having filmed an emergency surgery taken in 1978 for an ectopic pregnancy. "From 1990 to 1995, she underwent nine plastic surgery operations, intending to rewrite western art on her own body. One operation altered her mouth to imitate that of François Boucher's Europa, another changed her forehead to mimic the protruding brow of Leonardo's Mona Lisa, while yet another altered her chin to look like that of Botticelli's Venus. Was she trying make herself more beautiful? "No, my goal was to be different, strong; to sculpt my own body to reinvent the self. It's all about being different and creating a clash with society because of that. I tried to use surgery not to better myself or become a younger version of myself, but to work on the concept of image and surgery the other way around. I was the first artist to do it," she says, proudly" (Jeffries, 2009).6

Multi-dimensional and multi-method research design

The study reported here is part of a wider research program, which aims to investigate the socio-psychological interrelations between female-male beauty and aesthetic surgery in various social groups (young people with university training in Arts, Information Technology and Sports, members of internet forum discussions) in three European countries (Italy, Spain and Romania), in view of enlarging the study to other cultural contexts such as Brazil and Asia, where body culture assumes various meanings.

The general research program employs an integrated Multi-dimensional and Multi-method Research Design (de Rosa, 1990; Moscovici & Buschini, 2003), comprising three types of investigation, briefly described below:

1. Field study

| a) | Projective verbal techniques: | |

| • | Associative network | |

| • | Self conceptual Identification | |

| b) | Projective graphic techniques: | |

| • | Body-map | |

| • | Photolanguage | |

| c) | Structured verbal techniques: | |

| • | Involvement Level Scale | |

| • | Self - Attractiveness Scale |

2. Media analysis:

• Adverts content analysis from print and digital media

• Internet forum textual analysis

• Web - communities (social networks) conversational analysis

3. Experimental investigation - focused on the generative activity of mental images and emotions in the social representations of beauty and aesthetic surgery.

The section of the multi-method study, presented in this paper, has the following research goals:

• To witness the potential change in the social representations of masculine and feminine beauty in a synchronic manner in three cultural contexts, with different degrees of diffusion of aesthetic and plastic surgery, ranking Spain on the 3rd position, Italy on the 24th, while Romania takes the last place in the sample of countries listed - the 32nd (according to the 2002 statistics mentioned in the introduction).

• To investigate the relationships between social representations of masculine and feminine beauty and S.R. of aesthetic and plastic surgery in the samples differentiated in all the three countries by education with close/distant relations with aesthetics and body culture;

• To evaluate the social / subjective distinction - focusing on the emotional and imagistic content of the social representations of beauty and aesthetic/plastic surgery, comparing different social groups with different Self rated attractiveness, level of involvement, and Self Identification with various meaningful cultural referents.

Participants and population variable's definition

A total of 283 university students participated in our study, which employed a between subjects factorial design. The first set of independent variables comprised the socio-demographic variables: country, University Education and Gender. Participants' distribution in the various groups defined by them is shown in the Table 1:

Besides the socio-demographic variables, the participants in the study have been distributed according to the psychological variables respectively detected by our research tools, presented in the following section, as follows:

• Level of self - rated attractiveness

- low (141 participants) / high (142 participants)

• Level of self-involvement in the topic of aesthetic-plastic surgery:

- low (153 participants) / high (130 participants)

• Self-Identification Conceptual Network:

the distribution of the participants according to the specific self-identification with cultural referents for each of our participant made possible the selection of five new groups of subjects, differentiated on the basis of their maximum self-identification with:

- beauty (56 participants)

- body (62 participants)

- culture (59 participants

- nature (56 participants)

- soul (50 participants).

The statistic procedure employed in this respect and the role of independent and dependent varibales assigned in the multi-step analyses is described below, in the Results section.

Our hypotheses were:

• There are significant differences between the three national samples in the identification strengths with the cultural referents of the Self-Identification Conceptual Network.

• There are significant differences in the indexes generated by the Associative Network between the three national samples.

• There are significant differences in the content and structure of the social representations of beauty and aesthetic surgery between the groups generated by our independent variables: nationality, gender, study domain, self-attractiveness, involvement in the topic of aesthetic surgery, specific cultural identification referent.

• The content and structure of the social representations of aesthetic surgery is related to the social representations of feminine and masculine beauty in each of the three national samples.

The instruments employed in our investigation are:

• Associative Network (de Rosa, 2002, 2003, 2005), a projective measure useful for detecting the content, structure, polarity and stereotyping dimension of the semantic field evoked by "stimulus words". The participant is requested to write down all the words that come to mind in relation to the inductor phrase, and then rank their order and subjective importance, mark their valence and connect them in any way that he/she considers they should be linked. The Associative Network was used with the following inductor phrases: - Masculine beauty; - Feminine beauty; - Surgery; - Aesthetic surgery.

In the multi-step data analysis we used four types of information extracted from the responses to this instrument, described from the technical point of view in the Results section:

a) Stereotyping index,b) Polarity index, c) Inductive power and d) the dimensions that structure the textual corpus. At the first step of the analysis we used the a, b, c, elements as dependent variables and at second step in the cross-analyses of the results derived from different stimulus words or from various instruments, we have treated the same a, b, c, elements as independent variables in order to differentiate the population according to their psychological dimensions and representational systems.

• Self - attractiveness scale - requiring the participant to assess his / her level of attractiveness on a 6 points Likert scale. In the subsequent analyses, we used the level of involvement as independent variable, obtained by calculating the median of the scores and splitting the sample accordingly.

• Self-Involvement in the topic of aesthetic surgery scale - a 2 item scale, inspired by Rouquette's considerations about the role of proximity with the chosen object of representation (1994), detected by asking the participant to assess his / her involvement and, respectively, personal relevance of the topic of aesthetic surgery on a 6 points Likert scale. The correlation between the two measures was 0,82. In the subsequent analyses, we used the level of involvement as independent variable, obtained by calculating the median of the mean scores on the two items and splitting the sample accordingly.

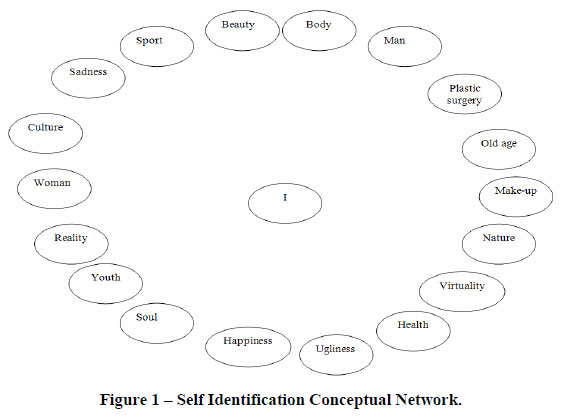

• Self Identification Conceptual Network, a projective verbal technique - developed by de Rosa - aimed at extracting the intensity of one's identification with various cultural referents. Participants have to use the figural construction presented in Figure 1, with the following instruction set:

| 1. | Draw a line connecting the word in the middle which means yourself with each of the words you think it should be connected. Don't draw more than 16 lines, and also indicate with number from 1 to 5 the degree of identification (1 = minimum, 5 = maximum identification). The words you will leave unconnected express a lack of relationship between yourself and that dimension. |

| 2. | Indicate with a + or - whether the connection between yourself and the respective dimension is positive or negative. |

Procedure

The combined questionnaire (with all instruments) was filled in by each participant in collective sessions of about 20 people; the order of the instruments was: Associative Network with the four inductor expressions, self - attractiveness scale, Self-Involvement in the topic of aesthetic surgery scale, Self Identification Conceptual Network.

Analysis of the Results

Results from the Self Identification Conceptual Network

In order to test the first hypothesis, our first approach to the data detected via Self-Conceptual Network technique was to identify the mean of associations between one's self and each of the 18 conceptual categories (cultural referents). The table 2 shows the results distinctively for the three national groups of participants.

The first phase of data analysis was the identification of significant identifications, defined as the identity referents towards which the national mean is significantly different from 0. The One Sample t Test applied on each of the 54 national means (3 countries x 18 referents) revealed the significant associations depicted in Figure 2. The positive associations are in the upward side, the negative - in the downward. It is interesting to observe that the one's identification with plastic surgery is positive both for Italian and especially for Spanish participants, whereas there is a negative link with Romanians, who also show a weaker link with Body and Beauty compared Italian and Spanish participants.

The second phase of data analysis, using the One Way ANOVA test and the Games - Howell post - hoc correction, was the comparison between the means of the three national samples, on each of the 18 cultural referents. The results of the comparisons are shown in Figure 3, by means of the different thickness of the lines that connect "I" with the respective referent. We used three intervals (degrees) of significant association: less than 1,5; 1.5 - 2 and higher than 2. The means in different interval are drawn with different thicknesses, and the difference between them is significant (at p < 0,05). Only the significant associations (as shown by the previous test) are represented: the positive ones by a continuous line and the negative by a discontinuous line.

Taking into account the most relevant results from the two sets of data analysis concerning the Self Identification Conceptual Network, we can make the following comments regarding each of the three countries under scrutiny:

a) in the Spanish sample, the connection to plastic surgery is positive, albeit weak, while those to happiness and youth are significantly stronger, compared to the other two national samples, but also strong connection between I and culture, health and a moderate positive connection between I and beauty, body, sport, nature, reality, soul. Also, we notice the absence of any negative associations, as well as the lack of connection to old age, ugliness and sadness - a result shared with the Italian participants.

b) in the Italian sample, we notice the absence of a significant association to plastic surgery and also between I and make-up and old age, and a weak negative connection to sadness and ugliness. Also, in comparison to the other two national samples, there is a weaker connection to soul, woman, man, reality as an identification referent. Italian participants identify more strongly with culture, youth and health than with beauty, body, sport and nature.

c) in the Romanian sample, we notice a moderate negative association to plastic surgery, which is an interesting result, considering the position of the country in the list presented above and the familiarization process this recent expanding phenomenon of aesthetic surgery represents. As the Italian participants, they show a weak negative connection to ugliness. Also, compared to the other two national samples, there is a strong negative association to old age, but also weaker positive connections (compared to the other 2 samples) to beauty, and to its other traditional cultural associates: body, nature, happiness and sport. As the other two samples, Romanian participants identify more strongly with culture, youth and health.

Regarding the specific focus of our research, the results showing a stronger link between one's self and body, beauty, and plastic surgery for Spanish and Italian than for Romanians, seem to be coherent with the degree of diffusion of aesthetic-plastic surgery in the three countries, as ranked in the 2002 survey of the statistic above quoted. They represent supplementary reference points to be used in the interpretation of the results of the following data analysis stages; as such, we will return to them in the Discussion section of this article.

The second approach on the data collected through the Self Identification Conceptual Network was aimed at the distribution of participants according to their specific identification category of each participant - an independent variable in our research design. In order to extract a specific identity reference for each participant, we assigned each subject to the category towards which he/she had the maximum standardized z score, computed inside his/her national sample. This maximum z score reflected the strongest identification of the participant, in the context of his/her national sample. We selected only the reference categories which contain at least 10% of participants, in order to ensure a greater validity of the differences to be noticed among them. Thus, we were left with 5 reference categories: body, nature, soul, culture and beauty.

In the final stage of this data analysis procedure, we distributed the participants in all the other (less frequent than our cutoff point of 10%) categories to the selected ones, by recalculating the z-scores only for the selected set, and reassigning each participant on the same criterion of the maximum z-score (see results reported in the section 3).

Results from the Associative Network

In this section, we present the results from data analysis based on the Associative Network instrument, using as inductors masculine beauty, feminine beauty and aesthetic surgery. For each of the three inductor expressions that we present, the first three groups of results (A, B and C) concern the second hypothesis - about the indexes generated by the Associative Network, while the fourth (D) concerns the third hypothesis - about the content and structure of each of the social representations, explored through the statistical method of lexical correspondence analysis.

Social Representations of Masculine Beauty

A. Stereotyping index. Computed as the number of "different" words associated by each group of subjects / total number of words associated by each group of subjects * 100, it represents a measure of the degree of dictionary's uniformity/differentiation of the corpus evoked by each group of subjects. According to the technique's creator (de Rosa, 2002, 186) "This calculation is not a measurement applied to each subject, but comes about by dividing the number of "different" words associated by the whole group by the total number of the words associated by the entire group.(...) In order to bring this new measurement (Y) to a value between -1 and +1 (rather than in a scale of 100) and to insure that the value of +1 corresponds to the maximum value of the stereotypy (and not vice versa), the values obtained are transformed via the following formula:

The stereotyping index values for the three national samples are: Italy: -0,69; Spain: -0,77; Romania: -0,88.

They reveal a low level of stereotyping in all three samples (especially among the Romanians), indicating richness in diversifying the dictionary about the masculine beauty.

B. Polarity index, computed as:

(the number of positive words-number of negative words) number of total words associated by each country sample

The polarity index values were very similar for all the three samples, showing a positive connotation of the semantic space related to the social representations of masculine beauty for the Italian, Spanish and Romanian subjects: Italy: 0,34; Spain: 0,38; Romania: 0,37.

C. "Inductive power". Computed as the number of elicited expressions / number of participants, it's a measure of the breadth of the semantic corpus associated to the inductor expression: the higher the index, the more numerous are these associations. The values of the index for the three national samples are:

- Italy: 103 participants who elicited 823 elicited expressions overall - 7,99 / participant

- Spain: 90 participants who elicited 525 elicited expressions overall - 5,83 / participant

- Romania: 90 participants who elicited 448 elicited expressions overall - 4,97 / participant

At a first glance at the results of this set of three measures, we can notice a relative homogeneity of the valence of the inductor in the three national groups - as shown by the similar values of the polarity indexes. Focusing on the differences, we can conclude that the Romanian sample uses the less stereotyped discourse, but also the less "vocal" - the inductor "masculine beauty" has the smaller inductive power. In the Italian sample, we find the opposite: the most stereotyped discourse, but also the higher inductive power - a very rich, yet homogenous, shared discourse.

D. Lexical correspondence analysis

The results of this method of data analysis (carried out using the software T-Lab 6.0) are presented in Figure 4. Participants' country was employed as active variable (depicted in Capital Letters: ITALY, SPAIN, ROMANIA) in the correspondence analysis, while the other independent variables of our research were used as illustrative variables (depicted in Capital Letters and Square Symbol: Participant's Gender and Faculty, Self-rated attractiveness, Level of Involvement and Self-Identification with cultural referents from Self Identification Network).

The correspondence analysis extracted two factors. Factor 1 (horizontal) explains 59,02% of the data inertia (variance). Defining words (active variables), in terms of their contribution to the factor, are presented in the Table 3.

We can interpret factor 1 as reflecting the opposition between:

- a person-centered and gender dependent view of masculine beauty, focused on physical and psychological traits, as a "masculinized" (virility, physical), self-sufficient definition (confidence, charm) , expressed on the positive semi-axis mainly by University Students of Sports, Male and those who identify themselves especially with Body and Beauty;

- social denominations of masculine beauty, characterized both by negative connotation (idiot, passing) and positive, in terms of rewards (success, TV, women), expressed on the negative semi-axis mainly by participants who identify themselves with Nature and Soul.

Factor 1 also denotes the clear opposition between two of the levels of our active variable (country), respectively Italians on the positive semi-axis and Romanian participants on the negative semi-axis, as described in more detail below.

Factor 2 (vertical) explains 40,98% of the data inertia (variance). Defining words, in terms of their contribution to the factor, are presented in the Table 4.

The negative semi-axis evokes a more "up-to-date" gender focused perspective on masculine beauty; it's an individualistic view, which, besides descriptive traits (man, handsome, dark skin) also includes references to less classical, stereotyped connotations, such as "metrosexual" or "sensual", - with the contribution of Female and participants who identify themselves with Soul, as illustrative variables - as opposed to the positive semi-axis, which is mostly defined by social connotations of status symbol (success and money) - mainly expressed by Male participants.

The comments on the "backbone" of the factorial structure presented above can be nuanced by taking into account the contribution of each national sample and the semantic elements strongest associated to it.

Overall, the Italian space of associations seems to depict a "classical" view on masculine beauty, with a strict reference to exterior landmark elements - shirt, beard, six pack, and also to the necessary psychological traits that accompany and complete it: arrogance, confidence, vanity, charm, putting it "to work" in the interpersonal realm.

Taking into account the levels of the illustrative variables with a significant contribution to the factors, we notice that this perspective is close to other three consonant categories of participants: males, students of Sports faculty, participants who tend to identify more with the body as a reference, but also with beauty.

In the Romanian sample we can observe represented a multiple discourse; on one side, there is a conscious view on the social rewards of masculine beauty - money, success, women, TV, but also on its supplementary musts-haves (attitude, clothing, talk, elegance). On the other, there is also a critique of the same social conditioning of masculine beauty: idiot, superficial, passing. The illustrative variables associated with this discourse are the identification with nature and soul, as opposites of the social fabric, which contaminates beauty. Finally, the connection to nature as an identity reference also underlines another definition of masculine beauty, as a "return to basics", in terms of body, young and special.

The specific trait of the Spanish discourse is its high saturation in exterior bodily characteristics: dark skin, tall, body, back, with a clear aesthetic perspective - attractive, sensual, and handsome. We could interpret it as being a definition of a stereotyped and romanticized modern male (the term man is also present), with appealing qualities especially to the females (as an identification referent), and to those with a stronger identification with soul.

Social Representations of Feminine Beauty

A. Stereotyping index. The values of the index for the three national samples are:

- Italy: -0,64; - Spain: -0,78; - Romania: -0,76, showing higher degree of stereotyping in the Italian's representations of feminine beauty.

B. Polarity index - The polarity index values were very similar and positively connotated for all the three samples, also for the social representations of feminine beauty, as we have already showed for the masculine beauty: Italy: 0,31; Spain: 0,33; Romania: 0,30.

C. "Inductive power": number of elicited expressions / number of participants

- Italy: 103 participants who elicited 922 elicited expressions overall - 8,95 / participant

- Spain: 90 participants - 525 elicited expressions overall - 6,1 / participant

- Romania: 90 participants - 493 elicited expressions overall - 5,47 / participant

As in the case of the previous inductor, the three polarity indexes of "feminine beauty" are practically equivalent. The other two sets of results show that the Italian sample used the most stereotyped discourse, but also the most "vocal", in the sense of evoking the most numerous associations per participant, as revealed by the high inductive power of the stimulus, while the Romanian sample had the smallest inductive power, and a stereotyping index similar to the Spanish sample.

D. Lexical correspondence analysis

The results of this method of data analysis are presented in Figure 5. As before, participants' country was employed as active variable (depicted in Capital Letters) in the correspondence analysis, while the other independent variables of our research were used as illustrative variables (depicted in Square Symbols).

The correspondence analysis extracted two factors. Factor 1 (horizontal) explains 55,6% of the data inertia. Defining words, in terms of their contribution to the factor, are presented in the Table 5.

The opposition which characterizes factor 1 could be synthesized again as between:

- a person oriented and gender dependent discourse, in terms of particular feminized personality nuances (sensuality, sweet) and visual focus points (body limbs - feet, hands), especially expressed on positive semi-axis by Male participants and those who self-identify themselves with Beauty; this result is similar to the reversed representations already evoked by the inductor Masculine Beauty;

- a gender independent and naturalistic view, which is not specifically focused on feminine beauty values and projects it on other more general appealing naturalistic qualities: youth, health, natural.

Also in this case, similar to Masculine Beauty, factor 1 denotes the opposition between two of the levels of our active variable (country), namely between participants in the study from Italy and Romania, as described below.

Factor 2 (vertical) explains 44,4% of the data inertia.

The negative semi-axis (also associated to the Spanish sample) of this factor seems to be centered on a combination of another set of feminine (woman) bodily focus points (skin, breasts, eyes), and personality traits (sincere, intelligence), significantly expressed by Females and those who identify themselves with Soul, as opposed to the two gender independent characteristics which define the positive semi-axis (youth, success), expressed on the positive semi-axis mainly by Males and those who identify themselves with Body.

The following step of interpretation is, as before, the in-depth analysis of the semantic and illustrative variables spaces of the discourses produced by participants distinctively for each national sample.

Overall, the Italian perspective is characterized by a double discourse on the same topic: beauty traits. On one side, we can extract a clear descriptive physical discourse (physical, feet, face, posture, hair, hands, gym), without any evaluative dimension. On the other, there is a conscious view of the interpersonal nature of beauty, centered on the elements which serve as a vehicle towards the perceiver - glance, charm, provoking, voice, sensuality, sweet, sensitive (and, maybe, also stupid to complete the feminine attractiveness norm) - and his emotional reactions to feminine beauty - joy, envy.

Taking into account the significant illustrative variables, one can notice that this complex view is shared mostly by those with the highest identification with beauty as a cultural referent, and is a product, mostly, of male participants.

Again, the Romanian discourse is not at all semantically homogeneous, presenting a mixed view, with references to:

- general characteristics (comprising what we might call "the gender independent and naturalistic perspective"), as health, youth, natural - hence its association to nature as participants' identification category;

- personality qualities which refuse any physical anchoring of beauty - unique, special, attitude;

- a socialized and sexualized view - sex, sexy, success, money, which, compared to the similar social perspective on masculine beauty shared by the Romanian sample, is freed from any negative evaluation.

The discourse on masculine beauty produced by Spanish participants contains, on one side, an extensive set of gender dependent physical characteristics - stereotypically positively marked - tall, breasts, tan, lips, slim, blonde, skin - assumed also by the female participants as significant illustrative variable. On the other, we notice a personality based definition, based on enduring traits - sincere, delicate, some of them with a feminist root: force, grace, even woman. This split view is shared also by those with a stronger identity association to soul.

Social Representations of Aesthetic Surgery

A. Stereotyping index. The values of the index for the three national samples are:

Italy: -0,64; Spain: -0,72; Romania: -0,61; differentiating the three national groups more than in the case of the masculine and feminine beauty representations.

B. Polarity index values were: Italy: -0,23; Spain: -0,05; Romania: -0,24; showing for all the three countries a slightly negative polarity, almost close to the neutral zone for the Spanish participants.

C. "Inductive power": The values of the index for the three national samples are:

- Italy: 103 participants who elicited 701 elicited expressions overall - 6,80 / participant

- Spain: 90 participants who elicited 463 elicited expressions overall - 5,14 / participant

- Romania: 90 participants who elicited 337 elicited expressions overall - 3,74 / participant

Synthesizing the three results presented above, we notice that the Italian discourse has the same level of stereotyping and negativity as the Romanian discourse, but once again is the most "vocal" of all three. The Spanish discourse is the least stereotyped and emotionally polarized, while for the Romanian sample, aesthetic surgery as inductor had the weakest inductive power, but the strongest negative valence.

D. Lexical correspondence analysis

The results of this method of data analysis are presented in Figure 6. As before, the participants' country was employed as active variable (depicted in Capital Letters) in the correspondence analysis, while the other independent variables of our research were used as illustrative variables (depicted in Capital Letters and Square Symbols).

Factor 1 (horizontal) explains 67,35% of the data inertia. Defining words, in terms of their contribution to the factor, are presented in the Table 7.

The negative semi-axis of Factor 1 contains both a negative judgment - repugnant, unnatural - and a reference to the aesthetic surgery in terms of social influence - mass-media, star, fame. This representation is significantly expressed by Females, University students of Arts, participants who identify themselves especially with Nature and Soul. The positive semi-axis seems to be mostly rooted in a psychological explanation of these decisions - insecurity, un-satisfaction - and it is expressed mainly by Males, Students of Faculty of Sports and those who identify themselves with Culture.

Also, factor 1 denotes the opposition between two of the levels of our active variable (participants' country): Romania and Italy, as described later in greater detail.

Factor 2 (vertical) explains 32,65% of the data inertia.

As illustrated in the Table 8, the positive semi-axis of this factor - with the significant positioning of the participants who identify themselves with Body - is defined in a single term - correction - which suggests a more neutral and legitimated view on such a debated topic, if compared with the opposing negative semi-axis, which depicts a perspective more conscious of its causes or the nature of this phenomenon (complex) and possible negative consequences (pain, risk), expressed mainly by participants who identify themselves with Culture.

The semantic space produced by the Italian sample reveals a certain preoccupation with the psychological correlates and, generally, with the individual motivation for such decision: unsatisfaction, insecurity, necessity, exteriority, change, stereotypes, old age, flaws. Also, it raises critically the controversial question of the ultimate real benefits offered by aesthetic surgery (useless, useful), mentioning the most common parts of the female body object of aesthetic surgery (breast, nose, lifting). This perspective is shared by male participants and those with beauty as an identity reference, and students in the faculty of Sports.

The reference points around which the semantic space is built by the Romanian sample are, at first, the motivational explanations for decisions or experiential consequences related to aesthetic surgery, perceived as motivated by despair or induced by the mass-media and the star/fame modern cultural system (and its association with sexy). This view and preoccupations with the explanatory level is endorsed by those Female participants and students in the Arts faculty, used to and eager to challenge societal aesthetic stereotypes. As the decisions to undergo aesthetic surgery receive mainly external attributions, rich people who undergo these procedures are seen as incapable of resisting the outside pressures, thus their personal evaluation becomes more drastic (stupid).

Second, from a descriptive point of view, aesthetic surgery can be a correction of some ugly features that provoke shame, yet leaving scars instead. As such, the marks of ugliness remain, as an ironic punishment for those who try to trick nature. This opposition is revealed by the evaluative categorization of aesthetic surgery as unnatural (thus revealing the significant positioning of the participants who refer to nature as identity category), evoking manipulation of the body (Botox, blood), perceived as repugnant.

The discourse evoked by the Spanish participants minimizes the motivations (repair, caprice, complex) and the focus is body centered (breast, abdomen, skin, fat). At the same time, it maximizes the negative consequences (risk, pain), suggesting what we might call a more detached, prudent view on the topic of aesthetic surgery. The similarity with the Italian semantic space extends also to the financial considerations - money, expensive; this vision is characteristic to the participants with culture as the specific category of identification. Also, the two national samples share the focus on specific body parts to be "improved" - nose, breasts, buttocks.

Overall, this common discourse evokes a more personal and direct relationship with the topic compared to the Romanian sample, probably an effect of the increased familiarization with the object of representation due to the larger diffusion of the practice of aesthetic surgery.

Discussion and Conclusions

The results presented above suggest various connections between the social representations of beauty (masculine and feminine) and of aesthetic surgery. They result in interrelated representational systems clearly differentiated by the various social groups, not only depending on their gender (and the representations that male and female participants express compared their own or other gender dependent criteria of beauty and aesthetic surgery) or university education (more focused on Body, like Sports students, or aesthetics, like Arts, or less centered on both, like students in Informatics), but also deeply related to psychological dimensions, like the participant differentiated by the highest self-identification with various cultural referents (Beauty, Body, Culture, Nature, Soul).

In particular, the transversal analysis of the results shows the coherent pattern systematically diversifying male and female participants:

• the males are usually positioned together with students of Sports and subjects highly identified with Body or Culture on representational semantic spaces, expressing gender dependent views of beauty and psychological justifications and explanations for aesthetic surgery, guided by its body centered view as tool for repair or correction, anchored in aesthetic normative criteria (especially for feminine sexualized body);

• the female participants are usually positioned together with students of Arts and those highly identified with Nature and Soul, expressing a more social denomination of beauty criteria, associated to status symbols and critically evaluating the aesthetic surgery as an unnatural and risking intervention, as a mass-media social influence phenomenon (especially among the participants from the country with the least diffused and more recent practice of aesthetic surgery, like Romania).

Regarding the influence of the variable University Education, it is also interesting to observe that students in Informatics never appear in the significant positioning defined by the factorial organization of the semantic space, therefore expressing a more neutral representation less anchored to specific differentiated poles.

Contrary to our expectations and to previous results of the literature that investigates both the factors that may increase the likelihood of undergoing cosmetic surgery in a non-patient population7 and the postoperative satisfaction following cosmetic surgery8, the subjective psychological dimensions taken into account (self-rated attractiveness and self - involvement in the topic of aesthetic surgery) did not prove to be significantly related to any factor in the three correspondence analyses performed - on feminine and masculine beauty, respectively aesthetic surgery. In a certain degree, this could be due to the actual measures of these variables. Keeping in mind the number and complexity of the tasks required by the other tools of our multi-method research approach, the two dimensions mentioned above were measured through single, respectively double item six-point response scales, that could not offer a high degree of differentiation among participants. On the other side, such results might reveal the lack of relevance of these subjective evaluations to the social representations of the issues tackled in our research, at least when compared to other, more important dimensions - such as one's self - identification with cultural referents or gender.

Another possible explanation for the lack of significance of self-rated attractiveness could be the dual and oppositely nature of the relationships between aesthetic appearances and aesthetic surgery, both in the social thinking and practices. On one side, the traditional view of cosmetic surgery as a weapon in the "fight against ugliness" would suggest a stronger appeal of these procedures for those lacking self-confidence in their looks. On the other, on psychological grounds related to mental focus and salience of the physical traits, the opposite hypothesis could be defended, namely that the "already beautiful" should be more drawn into cosmetic surgery, redefined as "another form of make-up" rather than "revolution of looks", as a correction of imperfections rather than a massive invasion of the body. This explanation is supported by many aesthetic surgeons who have often declared (in TV and magazine interviews) that most of their patients are very beautiful woman, who do not need any body correction, but who are over worried by their fears of losing their beauty.

This double discourse - having as rationale the targeting of both categories of self-rated attractiveness - could be responsible for the relative homogeneity of the textual corpus elicited in our research by the two groups.

Furthermore, taking into account the cross-countries cultural variable supposed to be influenced by the diverse degree of the familiarization and diffusion of the aesthetic surgery in the country, the various critical positions summarized in the introductory part seem to find different degrees of relevance to the contents expressed by our three national samples. As a synthesis of our results, among the Italian participants, beauty is mainly defined by its physical, but also by interpersonal dimensions. The latter represent additional resources in the attractiveness equation, and they are expected to compensate, to some degree, the accidental drawbacks of the physical endowment. This could justify the intense negative charge of aesthetic surgery, which becomes an understandable option only for those in psychological need for an "update" of their beauty status. As the interpersonal capabilities still play a major part in the attractiveness play, aesthetic surgery reflects the weakness of the individual and solves an insignificant part of his/her real identity, as an expensive and failed technological solution to a psychological problem. This dialogue between the inner sources of decisions to undergo aesthetic surgery and its questionable outputs share with the feminist liberal perspectives the focus on the individual and his/her struggles to meet some more or less personal criteria in terms of appearance.

The representations expressed by the Spanish participants evoke a vision of beauty of both genders gravitating around the physical traits, yet with strong references to personality stereotyped dimensions. In this context, aesthetic surgery is integrated as a personal choice of modifying specific beauty - relevant body parts, but keeping in mind, at the same time, its potential negative consequences. This detached, conscious perspective builds upon the rational utility criteria, in terms of the gains and losses balance. Overall, it renders the view of aesthetic surgery close to the first liberal feminist perspective presented, as an acceptable - in some limits - way to address the cultural pressures and exterior definitions of beauty, with an intense awareness of the alternative criteria that should define it - one's personality.

The view of aesthetic surgery expressed by the Romanian participants in the study is a negative one, as an unjustified alteration, falsification of the natural prerequisites of beauty. Thus, it is a phenomenon attributed to social pressure, and then it carries the social stigmata of the "mystifying". The decisions to undergo aesthetic surgery are, thus, motivated by external and general pressure agents, as mass-media or the celebrity system, an explanation similar to the radical feminist view. The increased frequency of these interventions is seen by our Romanian participants as a sign of the progressive and unstoppable contamination with a "virus of superficiality", which threatens what should be every one's private possession: the body. As such, the relationships between the social representations of beauty and of aesthetic surgery evoke a more general psychological conflict between individual and societal value's referential systems in the Romanian sample.

Our results derived from multiple techniques and indexes can also be justified invoking a kind of split between "normative" representations and diffused practices, between generally negative connotated representations of aesthetic surgery in all the three national groups of participants (although with some differences already discussed above) and an impressive diffusion of the phenomenon of the increasing number of the aesthetic surgery interventions (even among adolescents and very beautiful women). Briefly stated, people tend from one side to criticize and negatively evaluate (probably due to a residual social desirability criteria against the body artificial manipulation seen as falsification of the natural beauty), whilst the practice becomes more and more socially shared. This can also explain the increasing phenomenon of the cosmetic tourism or medical tourism linked to the aesthetic surgery as international market that push patients out of their country and their social networks to do intervention protected by anonymous context (see Medical Tourisms Survey Results of the ISAPS by Staffieri, 2010, or Nassab, Hammett, Kaur, Greensill, Dhital, & Juma, 20109).

The various positions on the topic of cosmetic surgery, which served us as a reference point in the interpretation of our results, illustrate the multi-focal views, which mark the social dimension of the body, as product of social representations. Each position - identifiable in the social representations expressed by our participants - represents a different definition of the relationships between one's body and the societal insertions of the individual regarding the pressures to enhancing his/her aesthetic appeal. As such, these views can contribute to a reading of the cosmetic surgery issue through the lens of the social representations theory in several ways:

First, the significant links that they show between various cultural objects - beauty, gender, power, self-realization, inner/outer self, etc. - suggest that, in order to comprehensively investigate the topic of cosmetic surgery, one has to take into account an entire set of nested social representations. These multiple social representations form a complex semantic and evaluative grid through which the choice of undergoing cosmetic surgery is socially determined; in other words, such decisions involve more than the criterion of one's physical aesthetic improvement.

Second, the various positions on the topic also define the boundaries of legitimate interventions on the body; as a result of all these socio-cultural premises, people either reject or accept cosmetic surgery as a tool for the purpose of beauty. This straightforward verdict constitutes a supplementary argument for considering cosmetic surgery as both an object of social representations, and also a social practice, in both senses strongly related to the social representations of beauty.

Finally, these views are informative for a social representations analysis of the issue because they also suggest hypothesis concerning more general changes of the subjective paradigm towards the body, in other words a certain dynamics of its social representations. After the "liberation" stage, as remarked by Jodelet, the view of the postmodern body as "fragmented" text for expressing one's identity represents a shift in the social representations of the body, specifically on two dimensions: on one side, it represents a cancelation of the usual condition of unity which has defined one's body, which, in the new paradigm, is conceived as a collection of parts; the sense of one's self is no longer conditioned by biological integrity, a cultural change partly driven and illustrated by various medical advancements (artificial robotic-like limbs, organ transplant technology, new cosmetic surgery procedures, etc.). On the other side, this fragmentation allows the body to play a more complex and visible role in the expression of one's inner self. As such, the general category of body-modification techniques includes various ways in which the body can be used as a textual material in the outside writing of one's true identity. This also represents a drastic change in the cultural apprehension of the body, inserting it - besides the power or competition social relationships - in the communicative chain between the individual and society: the body becomes another form of language. In the light of these new social representations, cosmetic surgery is one of the technological means available in order to adapt one's body to the inner self - and thus to express itself on the social stage.

References

Abric, J. C. (Ed.) (1994) Pratiques sociales et représentations, Paris: Presse Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

APS (Association for Psychological Science) (2011). Beauty is in the Mind of the Beholder, Observer, 4(4),18-22. (Retrieved on April, 27 2011 from: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/publications/observer/2011/april-11/beauty-is-in-the-mind-of-the-beholder.html). [ Links ]

Atiyeh, B. S., Kadry, M., Hayek, S. N., & Musharafieh, R. S. (2008). Aesthetic surgery and religion: Islamic law perspective. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 32,1-10. [ Links ]

Balsamo, A. (1997). Technologies of the gendered body: Reading cyborg women. Durham (NC): Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Berry, B. (2007). Beauty bias: Discrimination and social power, Westport (CT): Praeger/Greenwood. [ Links ]

Berry, B. (2008). The power of the looks: Social stratification and physical appearance. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Brickman, B. (2004). 'Delicate' Cutters: Gendered Self-mutilation and attractive flesh in Medical Discourse. Body & Society, 10(4),87-111. [ Links ]

Brown, A., Furnham, A., Glanville, L., & Swami, A. (2007). Factors that affect the Likelihood of Undergoing Cosmetic Surgery, Aesthetic Surgery Journal , 27(5),501-508. [ Links ]

de Rosa, A. S. (1990). Per un approccio multi-metodo allo studio delle rappresentazioni sociali. Rassegna di Psicologia, 3,101-152. [ Links ]

de Rosa, A. S. (1994). From theory to meta-theory in S.R.: the lines of argument of a theoretical-methodological debate. Social Science Information, 33(2),273-304. [ Links ]

de Rosa, A. S. (2002). The "Associative Network": a technique for detecting structure, contents, polarity and stereotyping indexes of the semantic fields. European Review of Applied Psychology, 52(3-4),181-200. [ Links ]

de Rosa, A. S. (2003). Le "réseau d'associations": une technique pour détecter la structure, les contenus, les indices de polarité, de neutralité et de stéréotypie du champ sémantique liés aux Représentations Sociales. In J. C. Abric (Ed.), Méthodes d'étude des représentations sociales (pp. 81-117). Paris: Editions Erès. [ Links ]

de Rosa, A. S. (2005). A "Rede Associativa": uma técnica para captar a estrutura, os conteùdos, e os ìndices de polaridade, neutralidade e estereotipia dos campos semànticos relacionados com a Representações Sociais. In A. S. Paredes Moreira (Ed.), Perspectivas Teorico-metodològicas em Representações Sociais, (pp. 61-127). Editora Universitária - UFPB. [ Links ]

de Rosa, A. S. (Ed.) (2012). Social Representations in the "Social Arena". New York - London: Routledge. [ Links ]

de Rosa, A. S., & Carli, L. (1980). Il corpo come mediatore di sviluppo, Rivista di neuropsichiatria infantile, 226,499-512. [ Links ]

Eco, U. (2004). Storia della bellezza, Milano: Bompiani. [ Links ]

Eco, U. (2007). Storia della bruttezza, Milano: Bompiani. [ Links ]

Flament, C. (1989). Structure et dynamique des représentations sociales. In D. Jodelet (Ed.), Les représentations sociales (pp. 224-239), Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Frank, A. (1998). How Images Shape Bodies. Body & Society, 4,101-112. [ Links ]

Gimlin, D. (2000). Cosmetic Surgery: Beauty as Commodity. Qualitative Sociology, 23(1),77-98. [ Links ]

Gimlin, D. (2002). Body work: Beauty and self-image in American culture. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press. [ Links ]

Graham, L. R., Rawlings, E., & Rigsby, R. (1994). Loving to survive: Sexual terror, men's violence and women's live. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Hanisch, C. (1970). The personal is political. In S. Firestone & A. Koedt (Eds.), Notes from the second year: women's liberation: major writings of the radical feminists. New York: Radical Feminists (Reprinted in: D. Keetley; & J. Pettegrew (Eds) (2005), Public women, public words: A documentary history of American feminism. Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ])

Jeffreys, S. (2005). Beauty and misogyny: harmful cultural practices in the West. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jeffreys, S. (2009). Orlan's art of sex and surgery. (Retrieved on May 11, 2011 from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/jul/01/orlan-performance-artist-carnal-art). [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1981). Représentations, expériences, pratiques corporelles et modelés culturels. Les colloques de l'INSERM « Conceptions, mesures et actions en santé publique », INSERM, vol.104:377-396. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1984a). Représentations sociales: phénomènes, concept et théorie. In S. Moscovici (Ed.), Psychologie sociale. (pp. 357-78). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1984b). The representation of the body and its transformations. In R. M. Farr & S. Moscovici (Eds), Social Representations (pp. 211-237). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1994). Le Corps, la personne et autrui. In S. Moscovici (Ed.), Psychologie Sociale Des Relations À Autrui. (pp. 41-68). Paris: Nathan. [ Links ]

Kaw, E. (1994). "Opening" faces: The politics of cosmetic surgery and Asian American Women. In N. Sault (Ed.) (1994), Many mirrors: Body Image and Social Relations (pp. 241-265). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Keenan, K. (2009). Review to B. Berry (2008). The power of the looks: Social Stratification and Physical Appearance. Aldershot: Ashgate. (Retrieved on November 14 2010 from http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/1/reviews/keenan.html) [ Links ]

Lorenzo, G. L., Biesanz, J. C., & Human, L. J. (2010). What is beautiful is good and more accurately understood: Physical attractiveness and accuracy in first impressions of personality. Psychological Science, 21,1777-1782. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (Ed.) (1984). Psychologie sociale. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (2000). Social Representations: Explorations in Social Psychology. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S., & Buschini, F. (Eds.) (2003). Les methodes des sciences humaines. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Nassab, R., Hammett, N., Nelson, K., Kaur, S., Greensill, B., Dhital, S., & Juma, A. (2010). Cosmetic tourism: Public opinion and analysis of information and content available on the Internet. Aesthetic Surgery, 10(3),465-469. [ Links ]

Nahai, F. (2010). ISAPS President. Celebrating our collective success. In ISAPS NEWS, 4(2) http://www.isaps.org/uploads/news_pdf/ISAPS_NL_Interactivefred_Vol4_Num2.pdf p.3 [ Links ]

Negrin, L. (2002). Cosmetic surgery and the eclipse of Identity. Body and Society, 8,21-42. [ Links ]

Ortega, F. (2008). O corpo incerto: corporeidade, tecnologias médicas e cultura contemporânea. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond. (tr.it 2009 Il corpo incerto. Bio-imaging, body art e costruzione della soggettività, Torino: Antigone Edizioni). [ Links ]

Papenburg, P., & Zarzycka, M. (Eds.) (2011). Carnal aesthetics: transgressive body imagery and feministpPolitics. New York/Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan (under review). [ Links ]