Temas em Psicologia

ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.27 no.4 Ribeirão Preto out./dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2019.4-15

ARTICLE

Influence of group membership, moral values and belief in a just world in blaming the victim

Influência da pertença grupal, valores morais e crença no mundo justo na culpabilização da vítima

Influencia de la pertenencia grupal, valores morais y creencia en el mundo justo en la culpabilización de la víctima

Iara Maribondo AlbuquerqueI,II ; Ana Raquel Rosas TorresI

; Ana Raquel Rosas TorresI ; José Luis Álvaro EstramianaII

; José Luis Álvaro EstramianaII ; Alicia Garrido LuqueII

; Alicia Garrido LuqueII

IUniversidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brasil

IIUniversidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spaña

ABSTRACT

This study investigated the relationship between the victim's group membership and secondary victimization she suffers, moderated by Moral Values and Belief in a Just World (BJW). The victim of the ingroup was blamed more for the sexual violence she suffered (Study 1, N = 250). In turn, that relationship was moderated by binding values (Study 2, N = 117) and by BJW (Study 3, N = 258). Together, the results suggest that the victim blaming is greater when she belongs to the ingroup; and that this relationship is predicted by high adherence to binding values and low adherence to BJW. This research contributes to the extent that it demonstrates that the relationship between adherence to binding values and victim derogation does not occur exclusively at the cognitive level, as information processing in which high adherence to these values would produce greater secondary victimization regardless of group membership of the victim. Additionally, it highlights the importance of considering the psychosocial processes underlying violence against women in order to promote more effective discussions and actions.

Keywords: Secondary victimization, moral values, Belief in a Just World.

RESUMO

Este trabalho investigou a relação entre pertença grupal da vítima (endogrupo vs. exogrupo) e vitimização secundária por ela sofrida moderada pelos valores morais e Crença em um Mundo Justo (CMJ). Em consonância com estudos anteriores, a vítima do endogrupo foi mais responsabilizada pela violência sexual por ela sofrida (Estudo 1, N = 250). Por sua vez, essa relação foi moderada pelos valores vinculativos (Estudo 2, N = 117) e pela CMJ (Estudo 3, N = 258). Em conjunto, os resultados sugerem que a responsabilização da vítima de violência sexual é maior quando ela pertence ao endogrupo; e que esta relação é predita pela alta adesão aos valores vinculativos e baixa adesão à Crença em um Mundo Justo (CMJ). Esta investigação traz contribuições na medida em que demonstra que a relação entre adesão aos valores vinculativos e a derrogação da vítima não ocorre exclusivamente ao nível cognitivo, como um processamento de informação no qual a alta adesão a esses valores produziria maior vitimização secundária independente da pertença grupal da vítima. Adicionalmente, sinaliza a importância de considerar os processos psicossociais subjacentes à violência contra as mulheres com a finalidade de promover discussões e ações mais efetivas.

Palavras-chave: Vitimização secundária, valores morais, Crença em um Mundo Justo.

RESUMEN

Este estudio investigó la relación entre la pertenencia a un grupo de la víctima y la victimización secundaria que sufre, moderada por los valores morales y la creencia en un mundo justo (BJW). Se culpó más a la víctima del ingroup por la violencia sexual que sufrió (Estudio 1, N = 250). A su vez, esa relación fue moderada por los valores de enlace (Estudio 2, N = 117) y por BJW (Estudio 3, N = 258). Juntos, los resultados sugieren que la culpa de la víctima es mayor cuando pertenece al ingroup; y que esta relación se predice por una alta adherencia a los valores de unión y una baja adherencia a BJW. Esta investigación contribuye en la medida en que demuestra que la relación entre la adherencia a los valores vinculantes y la derogación de la víctima no se produce exclusivamente a nivel cognitivo, ya que el procesamiento de la información en el que la alta adherencia a estos valores produciría una mayor victimización secundaria independientemente de la pertenencia al grupo de la victima. Además, destaca la importancia de considerar los procesos psicosociales subyacentes a la violencia contra las mujeres para promover debates y acciones más efectivas.

Palabras clave: Victimización secundaria, valores morales, creencia en un mundo justo.

Violence against women continues to produce increasingly alarming data. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), although the numbers are a partial reflection of reality, given the underreporting of cases, they are sufficient to define this serious violation of human rights and public health problem as a pandemic. The maintenance of this scenario is also due to the naturalization of phenomena such as secondary victimization which fuels the cycle of violence against women.

Following this line of argument, the victim blaming for negative events, as one of the forms that secondary victimization can take, has been identified in various situations (Correia & Vala, 2003). Previous studies have shown that rape victims are vulnerable to this phenomenon (Campbell et al., 1999; Cubela, 1999) and are considered more to blame for the violence suffered in comparison to the victims of other types of crime (Angelone, Mitchell, & Lucente, 2012).

The propensity to attribute blame to rape victims has been examined by investigations in Social Psychology since the 1970s (Calhoun, Selby, & Warring, 1976; Cann, Calhoun, & Selby, 1979; Donnerstein & Berkowitz, 1981; Janoff-Bulman, Timko, & Carli, 1985; Muehlenhard, 1988; Muehlenhard & Rodgers, 1993; Ståhl, Eek, & Kazemi, 2010). In the meantime, although different theories have been proposed intending to understand this phenomenon, belief in a just world (BJW; Lerner, 1980; Lerner & Miller, 1978) has been frequently cited in the literature on sexual violence (Grubb & Turner, 2012).

Belief in a just world argues the existence of a motivational need for individuals to believe that the world is a fair place, where people have what they deserve and deserve what they have (Lerner, 1980; Lerner & Matthews, 1967). To preserve this belief, they are motivated to reestablish it whenever it is threatened (Correia & Vala, 2003). Thus, victim blaming for the violence he or she experiences helps restore the belief that the world is an orderly and just place (Grubb & Turner, 2012).

Following this line, previous investigations showed that high adherence to BJW predicts greater engagement in secondary victimization strategies (Aguiar, Vala, Correia, & Pereira, 2008; Correia & Vala, 2003; Correia, Vala, & Aguiar, 2001; Hafer & Bègue, 2005; Montada, 1998). More specifically, they have demonstrated the predictive value of BJW with respect to the derogation of sexual violence victims (e.g., Abrams, Viki, Masser, & Bohner, 2003; Sakallı-Uğurlu, Yalçın, & Glick, 2007; Valor-Segura, Expósito, & Moya, 2011).

However, while these studies have achieved significant results in testing the relationship between secondary victimization and BJW, Niemi and Young (2016) argued that this theoretical model may be limited by the content of moral values, which would account for most of the variation in attitudes in relation to victims. To follow this avenue of investigation, they used the multi-foundational model proposed by Moral Foundations Theory (MFT; Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009; Graham et al., 2013; Haidt 2001, 2007, 2012; Haidt & Joseph, 2004), which emerges in opposition to theories based on moral reasoning (Jia & Krettenauer, 2017; Kohlberg, 1969).

This model conceives of morality as a rapid, automatic process based on five intuitive foundations: harm, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity (Graham, et al., 2011; Haidt, 2007). Each of these foundations refers to a specific motivation. The foundation of harm relates to caring for offspring and those who need to be protected, while the foundation of fairness refers to acting according to the norms within one's group. Loyalty, in turn, concerns the protection of a group's interests against rival groups, and that of authority concerns the respect of those who are superior to oneself in the social hierarchy, thus preserving social order. Finally, the foundation of purity pertains to the motivation to be pure, both physically and spiritually, respecting the sacred and suppressing carnal desires (Yilmaz, Harma, Bahçekapili, & Cesur, 2016).

Among the five foundations proposed by Graham et al. (2011), three (loyalty, authority, and purity) refer to interactions between individuals, and are based on the ideas of A. Fiske (1992) that people tend to organize and coordinate their social life in terms of the relationships they have with other people. In contrast, according to Graham et al. (2011), the other two foundations, harm and fairness, would be focused on the individual's own needs and would stem from liberal ideas that hold that individual rights and duties would come first, before collective interests.

Considering morality based on individual and collective protection (Davies, Sibley, & Liu, 2014), the five moral foundations can be organized into two higher order factors: one individualizing and another binding. The first, intended to protect the rights of the individual, aggregates the foundations of harm and fairness, while the second, related to maintaining group harmony, encompasses the foundations of loyalty, authority, and purity (Graham et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2011; Silvino et al., 2016; Yilmaz et al., 2016). On the other hand, it is also important to emphasize that these higher order factors have a great conceptual proximity with the individualist-collectivist dimension of the model by Schwartz and Bilsky (1987, 1990). Thus, according to Schwartz (1992), individuals from collectivist cultures tend to be more concerned with maintaining group cohesion and harmony vs. the interests of the individual, while individualistic cultures show greater concern for the protection of the differences between group members and the defense of individual interests and rights vs. those collective.

Another aspect considered in the analytical perspective adopted in this research is based on the assumptions of social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), whose central idea is that when people categorize themselves as members of social groups, they begin to define themselves in terms of their group affiliations, and no longer due to their individual characteristics alone. This categorization accentuates intragroup similarities and differences between groups (Correia, Alves, Morais, & Ramos, 2015).

In this sense, studies have demonstrated the importance of considering the group affiliation of the victim to explain the phenomenon of blaming the victim based on the belief in a just world (Halabi, Statman, & Dovidio, 2015; Hayes, Lorenz, & Bell, 2013; Modesto & Pilati, 2017; Russell & Hand, 2017). Aligned with theoretical arguments presented up to this point, studies on secondary victimization have underscored that people with greater endorsement of individualizing values do not attribute blame for the event to the victim of a moral injury (Schein & Gray, 2015). In contrast, greater endorsement of binding values would be related to greater derogation of the victim, regardless of the type of crime and the political orientation of the observer (Niemi & Yong, 2016). However, it is noteworthy that no studies have been found in the literature that have tested the effect of the victim's group membership on attributed responsibility for the violence suffered, through adherence to moral values.

Given this theoretical framework and the importance of discussing the phenomena that contribute to the maintenance of the scenario of violence against women, some questions have arisen: does the greater derogation of the victim, conceived by prior research as originating from high adherence to binding values, occur as a processing of information flowing from psychosocial processes (e.g., group membership)? Does the relationship between group membership, moral values, and derogation of the victim not derive from BJW?

Research overview

Principally, the overall objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between the victim's group membership (ingroup vs. outgroup) and secondary victimization (operationalized by attributing blame to the victim for the violence suffered by the victim). In turn, the specific objectives were to analyze the moderating effect of moral values, and of belief in a just world, on this relationship.

To meet these objectives, five hypotheses were established, which guided the conduct of three empirical studies. Study 1 tested Hypothesis 1 (H1): the victim who is from the ingroup (Spanish) will be blamed more than the victim from the outgroup (Cuban). In Study 2 we tested: Hypothesis 2a (H2a), that the blame of the victim from the ingroup (Spanish) will be greater when there is high adherence to binding values; and Hypothesis 2b (H2b), that adherence to individualizing values will not predict greater victim blaming regardless of group membership. Finally, in Study 3 we tested: Hypothesis 3a (H3a), that adherence to belief in a just world, together with high adherence to binding values, will predict greater blame for the victim from the ingroup (Spanish); and Hypothesis 3b (H3b), that adherence to individualizing values will not predict victim blaming, regardless of group membership and participant adherence to BJW. This work was conformed to all American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines for research with human participants.

Study 1

In this first study, Hypothesis 1 (H1) was tested experimentally: the victim from the ingroup (Spanish) will be blamed more than the victim from the outgroup (Cuban).

This hypothesis was raised considering the theorizing by Lerner and Miller (1978) arguing that people are mainly concerned with their own world; and thus, the closer that injustices approach their group, the more they are motivated to explain or make sense of the event, than when it occurs in other settings (Aguiar et al., 2008).

Method

Participants and Design

This study included 250 persons from the general population (considering the 17 autonomous communities of Spain) of Spanish nationality, ages 17-67 years (M = 33, SD = 14.92). Sampling was non-probabilistic, snowball type (individuals selected to be studied invite new participants). The majority of participants (52%) were female. The design used was between participants and the designation of participants for each of the conditions occurred in a random manner.

Procedures

SurveyMonkey software was used to apply online questionnaires.

Instruments

Experimental Manipulation. The instru-ment used presented a vignette reporting a case of sexual violence involving two co-workers, Ana and Enrique, who are single and have known each other for some time. After a dinner, she invites him to continue conversing at her house, they exchange a few kisses, and against Ana's resistance, Enrique grabs her forcefully and continues kissing her until consummating the act.

The vignette varied on two levels, depen-ding on the victim's group membership. In one condition, the ingroup (Spanish victim) was emphasized. In the other condition, the victim was Cuban (outgroup member). Each participant responded to only one of the experimental conditions.

Victim blaming. Using a six-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all - 6 = Largely), participants had to indicate: To what extent do you think Ana is responsible for what happened?

Data Analysis

The analysis was conducted using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 20. For the comparison between the experimental conditions, a t-test for independent measurements was performed with the victim's group membership (Spanish vs. Cuban) as the independent variable and the victim blaming as the dependent variable.

Results

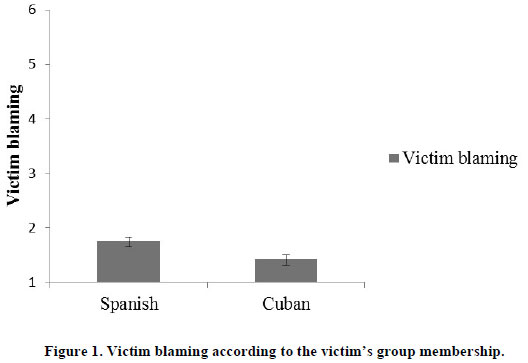

Based on estimated means, the t-test for independent measures revealed that, on average, the participants attributed more responsibility to the victim when she belonged to the ingroup - Spanish (M = 1.76, SD = 1.26) than when she belonged to the outgroup - Cuban (M = 1.43 , SD = .80). This difference, 0.132, 95% CI [-.586, -.065], was significant t (225) = -2.46, p = .015, d = .31. The means are summarized in Figure 1.

Partial Discussion

The result found supported Hypothesis 1 (H1) in demonstrating that the victim blaming varies according to her group membership. When the victim is from the ingroup (Spanish) she is blamed more.

This result is consistent with the hypothesis formulated by Lerner and Miller (1978) that people are more motivated to justify events when they occur in their own group; with the notion that the victim from the ingroup is more threatening to the belief in a just world (Correia, Vala, & Aguiar, 2007); and with the previous study conducted by Aguiar et al. (2008) where it is pointed out that the victim from the ingroup is blamed more for the undeserved fate.

Considering previous investigations that point to the influence of gender on the attribution of responsibility to the victim of sexual violence (Bendixen, Henriksen, & Nøstdahl, 2014; Durán, Moyan Megías, & Viki, 2010; Paul, Kehn, Gray, & Salapska-Gelleri, 2014), we tested the alternative hypothesis that the gender of the research participant influences his/her perception about the woman's blame for the violence she suffered.

However, on performing a 2 × 2 ANOVA, the statistical test revealed a non-significant interaction effect between the victim's group membership and the participant's gender, F (1, 246) = 1.06, ns. Corroborating previous studies (Mandela, 2011; Newcombe, Van den Eynde, Hafner, & Jolly, 2008; Strömwall, Alfredsson, & Landström, 2013), the result indicates that participant gender has no influence on the degree of responsibility attributed to the victim for the violence she suffered.

Given these results, another investigative path was taken. Thus, based on the study by Niemi and Young (2016) demonstrating that moral values would be the driving force for discrimination and blame regarding the victim, the second study presented here aimed to verify the moderating effect of moral values on the relationship between group membership of the victim and secondary victimization.

Study 2

This study aimed to experimentally test: Hypothesis 2a (H2a), that the blame of the victim from the ingroup (Spanish) will be greater when there is high adherence to binding values; and Hypothesis 2b (H2b), that adherence to individualizing values will not predict greater victim blaming regardless of group membership. It was expected that the relationship between the victim's group membership and secondary victimization would be moderated by binding values, such that high adherence to binding values (and not individualizing ones) would imply greater blame attributed to the victim from the ingroup (Spanish).

The hypotheses presented are based on the assumption from MFT (Graham et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2013; Haidt 2001, 2007, 2012; Haidt & Joseph, 2004) that while individualizing values are related to the protection of individual rights, avoiding harm (e.g., secondary victimization) and ensuring fairness, binding values are intended to assess actions in terms of loyalty, authority, and purity, and protect the group, even if this means the victim must be blamed (Graham et al., 2011; Niemi & Young, 2016; Yilmaz et al., 2016).

Method

Participants and Design

A total of 117 people from the general population (considering the 17 autonomous communities of Spain) of Spanish nationality, with ages between 18 and 55 years (M = 29.48, SD = 13.20) participated in this study. Sampling was non-probabilistic, snowball type (individuals selected to be studied invite new participants). The majority of participants (59%) were female. The design used was between participants and the assignment of participants for each of the conditions occurred in a random manner.

Procedures

SurveyMonkey software was used to apply online questionnaires.

Instruments

Experimental Manipulation. The instrument and the manipulation used in this study were the same as in Study 1.

Victim blaming. Using a six-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all - 6 = Largely), participants had to indicate: To what extent do you think Ana is responsible for what happened?

Moral Values. These were evaluated using a version of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ; Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2008; Graham et al., 2011) translated into Spanish by Bedregal and León (2008), through which 30 items represent the five moral foundations (loyalty, authority, purity, harm, and fairness). An example of the items of these foundations includes: (a) loyalty: "People should be loyal to the members of their family, even if they have done something wrong"; (b) authority: "If someone does or does not show disrespect for authority"; (c) purity: "Chastity is an important and valuable virtue"; (d) harm: "It will never be right to kill a human being"; and (e) fairness: "Justice is the most important requirement for a society". Using a principal components analysis with varimax rotation, the items were grouped into two factors [sample adequacy measure, KMO = .643, X2(10) = 206.23, p < .001]. A reliability analysis revealed a moderate index (Cronbach's α = .66) for Factor 1, representing the binding values (30.53% of the variance; high loadings for loyalty, authority, and purity values; and low loadings for harm and fairness values); and a strong index (Cronbach's α = .86) for Factor 2, representing the individualizing values (46.61% of the variance; high loadings for harm and fairness foundations; and low loadings for loyalty, authority, and purity foundations).

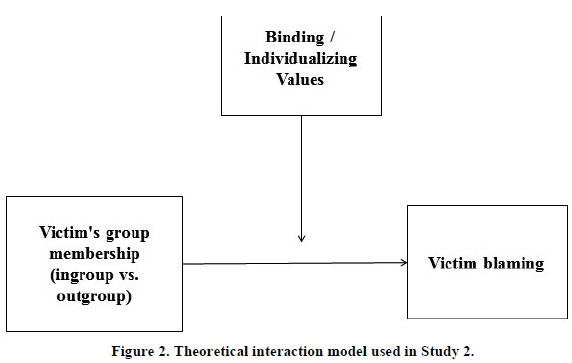

Data Analysis

The analyses performed in this study were conducted using the same Software as the previous study. For the tests of the effects of the binding values and individualizing values on the relationship between group membership and victim responsibility, linear regressions were run. The moderation hypothesis was tested, according to area recommendations (Hayes, 2013), with the use of PROCESS. The first one had the sexual violence victim's group membership (ingroup vs. outgroup) as an independent variable (IV), the victim blaming as the dependent variable (DV), and the binding values as a moderating variable (MV); The second had the same IV and DV, and the individualizing values as a moderating variable (MV). The theoretical interaction model used in this study is illustrated in Figure 2.

Results

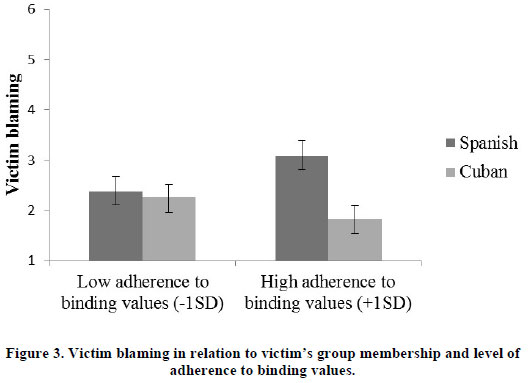

Multiple linear regression analyses revealed a statistically significant interaction effect between the victim's group membership (IV), victim blaming (DV), and binding values as a moderating variable (MV). The same result was not found regarding individualizing values.

The results indicate that the interaction between victim's group membership and adherence to binding values predicts, significantly, victim blaming, F (3, 113) = 3.16, p = .02. Analysis of the conditional effects indicated that differences in victim blaming in relation to group membership are statistically significant when there is high adherence to binding values (+1 SD above the mean) [b = 1.25, SE = .40, t(113) = 3.07, p = .002], since the victim from the ingroup (Spanish; Y = 3.08) was blamed more than the victim from the outgroup (Cuban; Y = 1.82). When there is low adherence to binding values (-1 SD below the mean), the differences are not statistically significant [b = .11, SE = .39, t(113) = .29, ns]. The means are summarized in Figure 3.

The same analysis of interaction was performed in relation to individualizing values, however this dimension did not present significant effects in the relationship between group membership of the victim and blame for the violation suffered [b = -.90, SE = .81, t(113) = - 1.11, ns].

Partial Discussion

Confirming hypotheses 2a (H2a) and 2b (H2b), the results observed indicate that the relationship between the victim's group membership and the victim blaming for the violence suffered is moderated by binding values, such that greater adherence to these values leads to greater blame of the victim from the ingroup; and that individualizing values do not predict greater victim blaming, regardless of the victim's group membership.

The results obtained corroborate the previous study that indicated the predictive effect of binding values regarding derogation of the victim (Niemi & Young, 2016); and previous research that defends the notion that individualizing values are related to protection of the individual, and do not predict harm, such as secondary victimization (Schein & Gray, 2015). In addition, confirming the results found in Study 1, these data highlight the effect of the victim's group membership on the phenomenon of blaming the woman for the sexual violence she suffered.

In order to analyze the moderating effect of belief in a just world, in the interaction found in the present study, Study 3 was carried out.

Study 3

The third study in this work examined hypotheses 3a (H3a), that adherence to belief in a just world, together with high adherence to binding values, will predict greater blame of the victim from the ingroup (Spanish); and Hypothesis 3b (H3b), that adherence to individualizing values will not predict victim blaming, regardless of group membership and participant adherence to BJW.

These hypotheses were formulated considering previous studies that have demonstrated the predictive effect of belief in a just world regarding the blaming of sexual violence victims (e.g., Abrams et al., 2003; Ferrão & Gonçalves, 2015; Sakallı-Uğurlu et al., 2007; Valor-Segura et al., 2011); and the argument that the relationship between this belief and derogation of the victim is limited by moral values (Niemi & Young, 2016).

Method

Participants and Design

A total of 258 persons from the general population (considering the 17 autonomous communities of Spain) of Spanish nationality, with ages between 18 and 58 years (M = 34.50, SD = 14.70) participated in this study. Sampling was non-probabilistic, snowball type (individuals selected to be studied invite new participants). The majority of participants (57.4%) were female. The design used was between participants and the assignment of participants for each of the conditions occurred in a random manner.

Procedures

SurveyMonkey software was used to apply online questionnaires.

Instruments

Experimental Manipulation. The instrument and the manipulation used in this study were the same as in Studies 1 and 2.

Victim blaming. Using a six-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all - 6 = Largely), participants had to indicate: To what extent do you think Ana is responsible for what happened?

Moral Values. To assess moral values, participants again completed the 30 items of the Spanish version of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ; Graham et al., 2011) translated by Bedregal and León (2008). Using principal components analysis with varimax rotation, the two-factor structure of the scale (sample adequacy measure, KMO = .616, X2(10) = 313.67, p < .001) was confirmed. A reliability analysis revealed moderate indexes (Cronbach's α = .73) for Factor 1 representing "binding values" (42.4% of the variance) and (Cronbach's α = .77) for Factor 2 representing "individualizing values" (30.0% of the variance).

Belief in a Just World (BJW). Version of the Lipkus scale (1991) validated in Spanish by Barreiro, Etchezahar, and Prado-Gascó (2014). The scale contains seven items, in a six-point Likert format (1 = Completely Disagree and 6 = Completely Agree), that represent belief in a just world. Examples of items about these beliefs include: I believe that people get what they have a right to have; I think people get what they deserve; Basically I think the world is a fair place. By means of a principal components analysis, using varimax rotation, the items were grouped into one factor [sample adequacy measure, KMO = .774, X2(21) = 356.45, p < .001]. A reliability analysis revealed a moderate index (Cronbach's α = .68). High scores on this scale indicated greater adherence to belief in a just world.

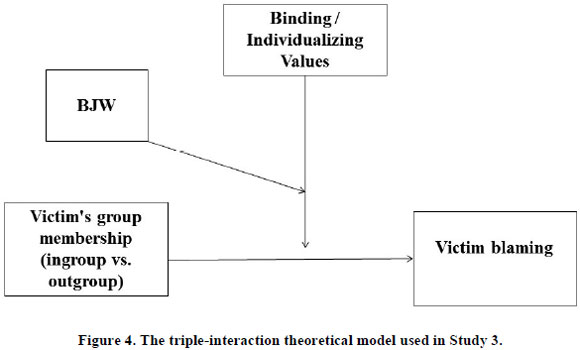

Data Analysis

The analyses carried out in this study were conducted using the same Software as the previous studies. For the tests of the effects of binding values, individualizing values, and belief in a just world on the relationship between group membership and victim responsibility, linear regressions were run. The moderation hypothesis was tested, according to area recommendations (Hayes, 2013), with the use of PROCESS. The first one had the sexual violence victim's group membership (ingroup vs. outgroup) as an independent variable (IV), the victim blaming as the dependent variable (DV), binding values as a primary moderating variable (MV1ª), and belief in a just world as a secondary moderating variable (MV2ª); the second had the same IV, DV, and MV2ª, and individualizing values as the primary moderating variable (MV1ª). The theoretical interaction model used in this study is illustrated in Figure 4.

Results

Multiple linear regression analyses revealed a statistically significant triple interaction effect between the victim's group membership (IV), victim blaming (DV), binding values (MV1ª), and BJW (MV2ª). The same result was not found in relation to individualizing values as the primary moderating variable.

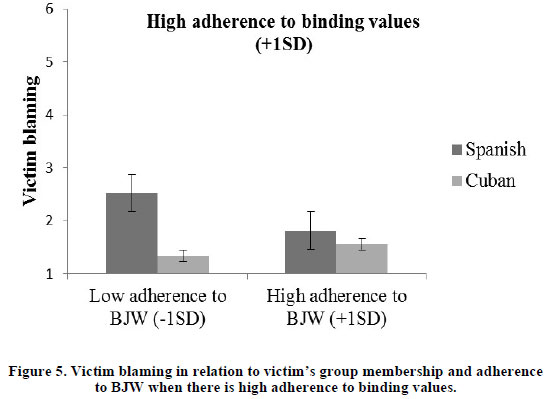

The results indicate that the triple interaction between victim's group membership, adherence to binding values, and BJW predicts, significantly, victim blaming, F (1, 250) = 3.74, p = .05. Analysis of the conditional effects indicated that the differences in the victim blaming in relation to group membership are statistically significant when there is high adherence to binding values (+1 SD above the mean) and low BJW (-1 SD below the mean) [b = 1.18, SE = .36, t(250) = 3.23, p = .001].

In the interaction between binding values and BJW, the violence victim blaming is greater when the victim is from the ingroup (Spanish; Y = 2.51) than when she is from the outgroup (Cuban; Y = 1.32). When there is high adherence to BJW (+1SD), even though adherence to binding values is high (+1SD), the differences in the victim blaming with respect to the victim's group membership are not significant [b = .26, SE = .23, t(250) = 1.03, ns]. The means are summarized in Figure 5.

The same analysis was performed with respect to individualizing values, however, it was found that they do not play a moderating role in the relationship of the victim's group membership and BJW with the woman's blame for the violence she suffered [b = .76, SE =. 44, t(250) = 1.73, ns].

Discussion

Together, the results supported hypotheses 3a (H3a) and 3b (H3b), since the sexual violence victim blaming varied according to the victim's group membership, the participants' high adherence to binding values, and adherence to belief in a just world; and since individualizing values, in turn, did not exert a moderating effect on the relationship between the victim's group membership, adherence to BJW, and secondary victimization.

Specifically, when belief in a just world was considered, together with binding values and victim group membership, to predict the woman's blame for the violence she suffered, low adherence to that belief made adherence to binding values more salient, producing greater blame for the victim from the ingroup. In contrast, high adherence to BJW turned this effect non-significant, resulting in greater secondary victimization independent of the victim's group membership.

These results suggest that high adherence to binding values predicts greater blame of the victim due to her group membership, when this is considered in isolation (see Study 2) or when it is associated with low adherence to BJW. Furthermore, they may indicate that high adherence to BJW limits the predictive power of binding values with regard to blaming the woman for the violence she suffered, as a result of her group membership.

These results contradict Niemi and Young's (2016) observations, in that they affirm that the relationship between binding values and greater judgment of the victims does not derive from belief in a just world. Moreover, they emphasize the predictive power of the victim's group membership, in interaction with high adherence to binding values and low adherence to BJW, with respect to derogation of the victim, offering a new route of investigation vis-à-vis previous studies that indicated secondary victimization as being due to high (and not low) adherence to BJW (e.g., Abrams et al., 2003; Ferrão & Gonçalves, 2015; Sakallı-Uğurlu et al., 2007; Valor-Segura et al., 2011).

In addition, the evidence found corroborates previous research that pointed to the absence of a relationship between adherence to individualizing values and victim blaming for the moral injury inflicted (Schein & Gray, 2015); and they add that this relationship also does not occur when other variables, such as the victim's group membership and BJW, are considered.

GENERAL DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Considering the current scenario in which violence against women continues to produce alarming numbers, this investigation becomes especially relevant for analyzing secondary victimization, one of the phenomena that contribute to the naturalization and persistence of this social problem.

Taken together, the results presented constitute an empirical test of the effect of the victim's group membership on the blame for the violence she has suffered, through binding values and belief in a just world. Consistent with previous studies, the data suggest that the victim's group membership influences secondary victimization (e.g., Aguiar et al., 2008); that high adherence to binding values predicts derogation of the victim (e.g., Niemi & Young, 2016); and that belief in a just world plays a predictive role regarding negative attitudes toward victims of sexual violence (e.g., Abrams et al., 2003; Ferrão & Gonçalves, 2015; Sakallı-Uğurlu et al., 2007; Valor-Segura et al., 2011).

More precisely, this research brings contributions insofar as it demonstrates that the relationship between adherence to binding values and derogation of the victim does not occur exclusively at the cognitive level, as information processing in which high adherence to binding values would produce greater secondary victimization independent of the victim's group membership (psychosocial variable); that high adherence to binding values leads to greater blame of the victim from the ingroup compared to the victim from the outgroup; that this effect is confirmed when low adherence to belief in a just world is considered jointly with binding values and the victim's group membership to predict secondary victimization; and that, yet, this effect becomes non-significant when high adherence to BJW is considered in this relationship, suggesting that high adherence to this belief limits the predictive power of binding values with respect to derogation of the victim, according to her group membership.

Additionally, the effect of participant gender was considered as an alternative hypothesis, however, the result of the analysis revealed that women and men blamed the victim of violence in an undifferentiated manner. This suggests that patriarchal culture is internalized regardless of gender and continues to reverberate in the processes of secondary victimization suffered by women victims of sexual violence, ensuring the maintenance of gender-based violence.

Notwithstanding, the studies carried out present some limitations. Considering previous investigations showing that closer relationship between victim and offender increases bias against the victim (e.g., Abrams et al., 2003; Buddie & Miller, 2001; Rebeiz & Harb, 2010) the results presented here may have been influenced by this aspect, since the scenario used presented a case of rape involving a couple of friends who had known each other for some time. Another limitation lies in the fact that participants were not asked about their socioeconomic status and whether they had already been victims of violence at some point in their lives. In this area, future investigations could replicate these studies, manipulating the closeness of the victim with the aggressor in these scenarios and considering those other aspects that were analyzed in the studies presented here.

In addition, in accordance with a previous study that demonstrated the influence of manipulation of the cultural schemes of individualism and collectivism in adherence to moral values (Yilmaz et al., 2016), another possibility would be to evaluate whether the priming of individualism would lead to greater adherence to the individualizing foundations and, consequently, to less derogation of the victim, as well as consider analyzing which other psychosocial processes influence this relationship between the victim's group membership, binding values, and secondary victimization (e.g., sexism, stereotypes, culture of honor).

Lastly, practices aimed at eliminating all forms of violence against women in different spheres should consider the psychosocial processes underlying this problem, such as those demonstrated on this occasion, so that action can occur in a more effective manner.

References

Abrams, D., Viki, G. T., Masser, B., & Bohner, G. (2003). Perceptions of stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1),111-125. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.111 [ Links ]

Aguiar, P., Vala, J., Correia, I., & Pereira, C. (2008). Justice in our world and in that of others: Belief in a just world and reactions to victims. Social Justice Research, 21,50-68. [ Links ]

Angelone, D. J., Mitchell, D., & Lucente, L. (2012). Predicting perceptions of date rape: An examination of perpetrator motivation, relationship length, and gender role beliefs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27,2582-2602. doi: 10.1177/08862-60512436385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/08862-60512436385 [ Links ]

Barreiro, A., Etchezahar, E., & Prado-Gascó, V. (2014). Creencia global en un mundo justo: validación de la escala de lipkus en estudiantes universitarios de la ciudad de buenos aires. Interdisciplinaria, 31(1),57-71. [ Links ]

Bedregal, P., & León, T. (2008). Cuestionario de Fundamentos Morales. MFQ-30. In MoralFoundations.org, The Moral Foundations Questionnaire: Spanish - MFQ30. Retrieved from http://yourmorals.org/haidtlab/mft/index.php?t=questionnaires [ Links ]

Bendixen, M., Henriksen, M., & Nøstdahl, R. K. (2014). Attitudes toward rape and attribution of responsibility to rape victims in a Norwegian community sample. Nordic Psychology, 6(33),168-186. doi: 10.1080/19012276.2014.931813. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2014.931813 [ Links ]

Buddie, A. M., & Miller, A. G. (2001). Beyond rape myths: A more complex view of perceptions of rape victims. Sex Roles, 45,139-160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1013575209803 [ Links ]

Calhoun, L. G., Selby, J. W., & Warring, L. J. (1976). Social perception of the victim's causal role in rape: An exploratory examination of four factors. Human Relations, 29,517-526. [ Links ]

Campbell, R., Sefl, T., Barnes, H. E., Ahrens, C. E., Wasco, S. M., & Zaracgoza-Diesfeld, Y. (1999). Community services for rape survivors: Enhancing psychological well-being or increasing trauma? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67,847-858. [ Links ]

Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., & Selby, J. W. (1979). Attributing responsibility to the victim of rape: Influence of information regarding past sexual experience. Human Relations, 32,57-68. [ Links ]

Correia, I., Alves, H., Morais, R., & Ramos, M. (2015). The legitimation of wife abuse among women: The impact of belief in a just world and gender identification. Personality and Individual Differences, 76,7-12. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.041. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.041 [ Links ]

Correia, I., & Vala, J. (2003). When will a victim be secondarily victimized? The effect of observer's belief in a just world, victim's innocence and persistence of suffering. Social Justice Research, 16,379-400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1026313716185 [ Links ]

Correia, I., Vala, J., & Aguiar, P. (2001). The effects of belief in a just world and victim's innocence on secondary victimization, justice, and victim's deservingness. Social Justice Research, 14,327-342. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014324125095 [ Links ]

Correia, I., Vala, J., & Aguiar, P. (2007). Victim's innocence, social categorization and the threat to the belief in a just world. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43,31-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.010 [ Links ]

Cubela, V. (1999). Impression about an ex-detainee person: Effects of target's sex and information about rape. In R. Roth (Ed.), Psychologists facing the challenge of a global culture with human rights and mental health: Proceedings of the 55Th Annual Convention of ICP. Landgericht, Germany: Pabst Science. [ Links ]

Davies, C. L., Sibley, A. G., & Liu, J. H. (2014). Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire: Independent Scale Validation in a New Zealand sample. Social Psychology. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000201 [ Links ]

Donnerstein, E., & Berkowitz, L. (1981). Victim reactions in aggressive erotic films as a factor in violence against women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41,710-724. [ Links ]

Durán, M., Moya, M., Megías, J. L., & Viki, G. T. (2010). Social perception of rape victims in dating and married relationships: The role of perpetrator's benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, 62(7-8),505-519. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9676-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9676-7 [ Links ]

Ferrão, M. C., & Gonçalves, G. (2015). Rape Crimes reviewed: The role of observer variables in female victim blaming. Psychological Thought, 8(1),47-67. doi: 10.5964/psyct.v8i1.131. http://dx.doi.org/10.5964/psyct.v8i1.131 [ Links ]

Fiske, A. P. (1992). Four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychological Review, 99,689-723. [ Links ]

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2008, July). The Moral Foundations Questionnaire: MFQ30. Retrieved from http://yourmorals.org/haidtlab/mft/index.php?t=questionnaires [ Links ]

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96,1029-1046. doi: 10.1037/a0015141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0015141 [ Links ]

Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2013). Moral Foundations Theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47,55-130. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00002-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00002-4 [ Links ]

Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101,366-385. doi: 10.1037/a0021847. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0021847 [ Links ]

Grubb, A., & Turner, E. (2012). Attribution of blame in rape cases: A review of the impact of rape myth acceptance, gender role conformity and substance use on victim blaming. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(5),443-452. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.06.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.06.002 [ Links ]

Hafer, C. L., & Bègue, L. (2005). Experimental research on just-world theory: Problems, developments, and future challenges. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 128-167. [ Links ]

Halabi, S., Statman, Y., & Dovidio, J. (2015). Attributions of responsibility and punishment for ingroup and outgroup members: The role of just world beliefs. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 18,104-115. [ Links ]

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4),814-834. [ Links ]

Haidt, J. (2007). The new synthesis in moral psychology. Science, 316,998-1002. doi: 10.1126/science.1137651. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1137651 [ Links ]

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York: Pantheon. [ Links ]

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2004). Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus, 133,55-66. doi: 10.1162/0011526042365555. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/0011526042365555 [ Links ]

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Hayes, R. M., Lorenz, K., & Bell, K. A. (2013). Victim blaming others: Rape myth acceptance and the just world belief. Feminist Criminology, 8(3),202-220. [ Links ]

Janoff-Bulman, R., Timko, C., & Carli, L. (1985). Cognitive biases in blaming the victim. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 21(2),161-177. [ Links ]

Jia, F., & Krettenauer, T. (2017). Recognizing moral identity as a cultural construct. Frontiers in Psychology. 8,412. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00412. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00412 [ Links ]

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. New York: Rand McNally. [ Links ]

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York: Plenum Press. [ Links ]

Lerner, M. J., & Miller, D. T. (1978). Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85(5),1030-1051. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.85.5.1030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.85.5.1030 [ Links ]

Lerner, M. J., & Matthews, G. (1967). Reactions to suffering of others under conditions of indirect responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5,319-325. [ Links ]

Lipkus, I. (1991). The construction and preliminary validation of a global belief in a just worlds scale and the exploratory analysis of the multi-dimensional belief in a just world scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(11),1171-1178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(91)90081-L [ Links ]

Mandela, I. N. (2011). Rape attribution for African- American students. Undergraduate Research Awards, Paper 10. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1031&context=univ_lib_ura [ Links ]

Modesto, J. G., & Pilati, R. (2017). "Nem todas as vítimas importam": Crenças no mundo justo, relações intergrupais e responsabilização de vítimas. Temas em Psicologia, 25(2),763-774. http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2017.2-18Pt [ Links ]

Montada, L. (1998). Belief in a just world: A hybrid of justice motive and self-interest. In L. Montada & M. J. Lerner (Eds.), Responses to victimizations and belief in a just world. New York: Plenum Press. [ Links ]

Muehlenhard, C. L. (1988). "Nice women" don't say yes and "real men" don't say no: How miscommunication and the double standard can cause sexual problems. Women and Therapy, 7,95-108. [ Links ]

Muehlenhard, C. L., & Rogers, C. S. (1993). Narrative descriptions of "token resistance to sex". In C. L. Muehlenhard (Chair), "Token resistance" to sex: Challenging a sexist stereotype. Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada. [ Links ]

Newcombe, P. A., Van den Eynde, J., Hafner, D., & Jolly, L. (2008). Attributions of responsibility for rape: Differences across familiarity of situation, gender, and acceptance of rape myths. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(7),1736-1754. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00367.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00367.x [ Links ]

Niemi, L., & Young, L. (2016). When and why we see victims as responsible: The impact of ideology on attitudes toward victims. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(9),1227-1242. doi: 10.1177/0146167216653933. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167216653933 [ Links ]

Paul, L. A., Kehn, A., Gray, M. J., & Salapska-Gelleri, J. (2014). Perceptions of, and assistance provide to, a hypothetical rape victim: Differences between rape disclosure recipients and nonrecipients. Journal of American College Health, 62(6),426-433. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.917651. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2014.917651 [ Links ]

Rebeiz, M. J., & Harb, C. (2010). Perceptions of rape and attitudes toward women in a sample of Lebanese students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 735-752. [ Links ]

Russell, K. J., & Hand, C. J. (2017, November). Rape myth acceptance, victim blame attribution and Just World Beliefs: A rapid evidence assessment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 37,153-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.008 [ Links ]

Sakallı-Uğurlu, N., Yalçın, Z. S., & Glick, P. (2007). Ambivalent sexism, belief in a just world, and empathy as predictors of Turkish students' attitudes toward rape victims. Sex Roles, 57(11-12), 889-895. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9313-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9313-2

Schein, C., & Gray, K. (2015). The unifying moral dyad: Liberals and conservatives share the same harm-based moral template. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41,1147-1163. doi: 10.1177/0146167215591501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167215591501 [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advanced and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advanced in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1-65). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward a Theory of the Universal Content and Structure of Values: Extensions and cross-cultural replications.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 58,878-891. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 550-562. [ Links ]

Silvino, A. M. D., Pilati, R., Keller, V. N., Silva, E. P., Freitas, A. F., Silva, J. N., & Lima, M. F. (2016). Adaptação do Questionário dos Fundamentos Morais para o Português. Psico-USF, 21(3),487-495. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712016210304 [ Links ]

Ståhl, T., Eek, D., & Kazemi, A. (2010). Rape victim blaming as system justification: The role of gender and activation of complementary stereotypes.Social Justice Research, 23(4),239-258. doi: 10.1007/s11211-010-0117-0. http://dx.doi.org/doi: 10.1007/s11211-010-0117-0 [ Links ]

Strömwall, L. A., Alfredsson, H., & Landström, S. (2013). Rape victim and perpetrator blame and the Just World hypothesis: The influence of victim gender and age. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 19(2),207-217. doi: 10.1080/13552600.2012.683455. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2012.683455 [ Links ]

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterrey, CA: Brooks-Cole. [ Links ]

Valor-Segura, I., Expósito, F., & Moya, M. (2011). Victim blaming and exoneration of the perpetrator in domestic violence: The role of beliefs in a just world and ambivalent sexism. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14(1),195-206. [ Links ]

Yilmaz, O., Harma, M., Bahçekapili, H. G., & Cesur, S. (2016). Validation of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire in Turkey and its relation to cultural schemas of individualism and collectivism. Personality and Individual Differences, 22,149-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.090 [ Links ]

Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Iara Maribondo Albuquerque

Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Cidade Universitária

João Pessoa, PB, Brazil 58051-900

Phone: +55833247-1097

E-mail: iaramaribondo@gmail.com

Received: 24/10/2018

1st revision: 21/12/2018

Accepted: 04/01/2019

Funding: This research had the financial support of Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) / Programa de Doutorado-sanduíche no Exterior (PDSE).

Authors' Contributions:

Substantial contribution in the concept and design of the study: Iara Maribondo Albuquerque, Ana Raquel Rosas Torres, José Luis Álvaro Estramiana, Alicia Garrido Luque.

Contribution to data collection: Iara Maribondo Albuquerque, José Luis Álvaro Estramiana, Alicia Garrido Luque.

Contribution to data analysis and interpretation: Iara Maribondo Albuquerque, Ana Raquel Rosas Torres, José Luis Álvaro Estramiana, Alicia Garrido Luque.

Contribution to manuscript preparation: Iara Maribondo Albuquerque, Ana Raquel Rosas Torres, José Luis Álvaro Estramiana, Alicia Garrido Luque.

Contribution to critical revision, adding intelectual content: Iara Maribondo Albuquerque, Ana Raquel Rosas Torres, José Luis Álvaro Estramiana, Alicia Garrido Luque.

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the publication of this manuscript.