SMAD. Revista eletrônica saúde mental álcool e drogas

ISSN 1806-6976

SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. (Ed. port.) vol.11 no.3 Ribeirão Preto set. 2015

https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v11i3p122-128

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

DOI: 10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v11i3p122-128

Family context and drug use in adolescents undergoing treatment

Samira Reschetti MarconI; Jennifer Oliveira de SeneII; José Roberto Temponi de OliveiraI

IPhD, Adjunct Professor, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil

IIUndergraduate student in Nursing, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil

ABSTRACT

In this study, the aim was to describe characteristics of the family context of adolescents undergoing treatment in the Alcohol and Drugs Psychosocial Care Center, Cuiabá, MT. This was a cross-sectional retrospective documental study analyzing the medical records of 74 service users receiving treatment. Results showed a predominance of males, with low levels of schooling and a high proportion of marihuana use. The majority had a satisfactory home life, did not get on well with the father figure and lived with other family members who used drugs. The findings indicate the importance of evaluating family factors in treatment, providing important information for developing comprehensive care which includes the user and their families.

Descriptors: Family Relationships; Family Characteristics; Disturbance Related Disorders Use; Adolescent.

Introduction

Over time, the way the family is organized in society has changes, making a variety of descriptions and functions possible, there now being a variety of different family configurations(1). However, irrespective of the configuration, the family is the basic unit of society, responsible for transmitting morals and values from the earliest stages of life well into adulthood, as well as being a space in which the adolescent will develop and undergo the changes and experimentation that characterize this stage of life(2).

The family context, the space in which relationships between the different members develop directly affect the children as they grow up and form a stable base in the midst of so many discoveries(2).

In adolescence, there is an intense search for a personal identity, as well as the need to stand out from family and peers, a moment at which a “psychological crisis” may occur, predisposing the adolescent to a situation of vulnerability, of risky behavior, as they are still being formed, integrating themselves into social norms and rules(3).

Data obtained in surveys on consumption of Psychoactive Substances (PS) confirm an increase in such use among children and adolescents. The first Household Survey, conducted in 2007 in the 107 largest Brazilian cities indicated that 48% of adolescents aged between 12 and 17 had consumed alcohol at least once. In 2005, this figure was seen to have increased to 54.3%(4)

A study of adolescents aged between 14 and 19 indicated that a trend for increasingly earlier onset of PS use, as well as highlighting unsatisfactory relationships and, above all, disappointment with parents as a motivation for their use(2).

Family contexts with unsatisfactory relationships, lack of dialogue, misunderstanding and PS abuse among parents or other family members in the household are conducive to PS use among adolescents, as it is in such environments that they will come across the role models they will follow(2,5).

Therefore, family interaction and ties may often be favorable to the adolescent user’s recovery and social life, as well as potentially encouraging attitudes that are incompatible with the treatment and with social life when they are fragile, generating conflict within the family context (6).

Thus, bearing in mind that drug use in adolescents has increased significantly in this country and begins at an increasingly earlier age, that the quality of inter-family relationships is essential to the development process of its members and that being aware of the adolescent’s family context is essential in planning care, this study aims to describe the characteristics of the family context of the adolescent undergoing treatment at the Alcohol and Drugs Psychosocial Care Center (CAPS ad), Cuiabá, MT

Material and methods

This was a cross-sectional retrospective documental study based on the medical records of CAPS ad service users in Cuiabá, MT, a public service specializing in treating children and adolescents who abuse alcohol and other drugs.

Between February and April 2012 the medical records of 74 service users undergoing treatment in the January 2011 – January 2012 period were analyzed, excluding the medical records of users who lived in shelters, those who did not have a parent or guardian responsible for them, those who visited the CAPS ad only once and those who did not reside in Cuiabá, MT.

In order to collect the data, a list was made of all service users who were authorized for highly complex treatment. As some service users had more than one record, from having begun and abandoned treatment, then later returned, the names were checked for repeated records, producing a final list of medical records.

The instrument used to collect the data was drawn up by the researcher, using the evaluation forms used by each professional in the service as a reference and selecting the questions that could meet the studies objectives, composed of socio-demographic variables related to PS use, family variables and PS use in family members. Once the instrument had been constructed, a pilot test was conducted on 10 medical records, aiming to verify its appropriateness and any possible difficulties from a lack of information in the documents. The descriptive analysis made use of simple frequency, mean and standard deviation and used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), program version 17.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitário Júlio Muller, Record nº095/CEP-HUJM/11.

Results

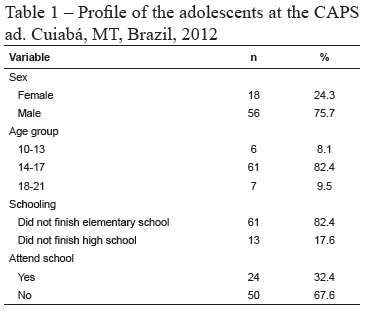

Table 1 shows the predominance of male adolescents (75.7%), aged between 14 and 17 (82.4%), single (86.5%), not having finished elementary school (82.4%), 67.6% did not attend school and 77.0% had no paid work.

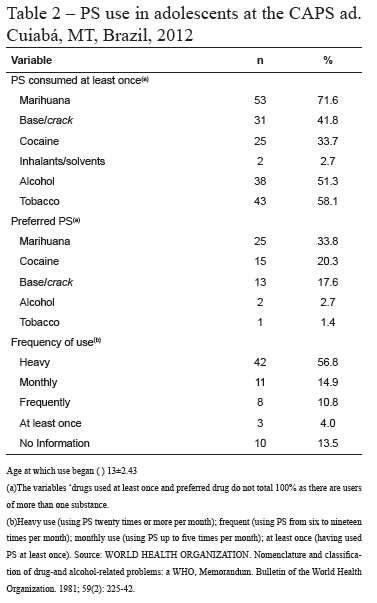

In Table 2, we can see that the mean initial age at which PS use began is 13, with the most commonly consumed PS being marihuana (71.6%), followed by tobacco (58.1%) and alcohol (51.3%). There was preference for marihuana (33.8%), with a pattern of heavy consumption (56.8%).

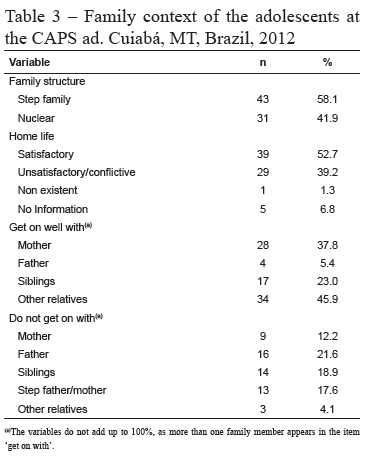

Regarding the family context, Table 3 shows the predominance of stepfamilies (58.1%), and satisfactory home life (52.7%). The majority of the adolescents had satisfactory relationships with other family members (45.9%) and an unsatisfactory relationship with their father (21.6%).

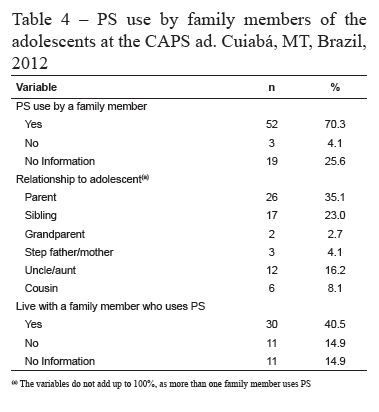

Table 4 shows the predominance of family members who also use PS (70.3%), with the highest percentage being parents (35.1%). It was observed that in 40.5% of records, the adolescent lived with another family member who used PS.

Discussion

The predominance of males in the study population reaffirms the findings in the literature concerning the higher number of males using PS treatment services(7-10). The trend for illegal substance use among males compared to females may contribute to this finding, as using such substances causes more visible and immediate harm, leading to treatment being sought, voluntarily or otherwise. Another aspect concerning the predominance of males at the CAPS ad concerned the prejudice against females using PS, making it more difficult to seek treatment. However, despite the lower levels of females seeking treatment, studies have shown the increased PS use among women (11-13).

In this study, the predominant age group was single 14 to 17-year-olds, explained because this is a service specifically for adolescents. However, it is noteworthy that there are adolescents aged between 10 and 13 undergoing treatment at the CAPS ad, confirming a fact that has been widely discussed in the literature, PS use at beginning at an increasingly early age(14).

A study of adolescents hospitalized for alcohol dependency treatment in Curitiba, PR, shows experimentation with PS in the 6 to 10-year-old age group(7). The authors highlight the user’s predisposition to developing dependency early in life, as well as to psychological and cognitive damage at this stage in life. Such early use was also found in a study conducted with students in Goianá, MG, as the majority reported having used PS between thirteen and fifteen years of age (45.1%), followed by between ten and twelve years of age (24.6%)(13). Other studies with adolescent PS users undergoing treatment have found similar ages to those of this study(5,7).

Regarding the level of schooling, a high proportion of the users had not finished elementary school, which is of concern given their age. It is also noteworthy that, at the time the study was conducted, 67.8% of users were not attending school. This plays an important role in the education and socialization of adolescents and preventing drug use should begin at there as, together with the family, the school is responsible for transmitting morals and values and is the second socialization group(14).

The school problems of adolescent PS users have been demonstrated in the literature, highlighting the difficulties users have in following the rules and limits the school environment imposes, and meaning that educators must be prepared to deal with this clientele (8,14). The CAPS ad, as an articulator in the network, plays an essential role in this process, demystifying and providing support for those in charge of the school, as well as for teachers, in receiving the adolescents.

For 71.6% of the adolescents surveyed, marihuana was the preferred PS, a percentage even higher than those of legal PS (51.3% for alcohol and 58.1% for tobacco). These findings are in line with the national trend for the general population of marihuana as the most commonly used illegal drug(10). It is noteworthy that although the percentages for legal drug use are lower than those for marihuana, they are still above those for use among students in the public school network(2,11).

The prevalence of heavy use, 20 times or more within the last month, among the adolescents may predispose them to develop dependence, in addition to constant use leading to serious effects on all spheres of their lives. The heavy use found in 56.8% of adolescents in this study attracts attention given the seriousness of this type of use at such a young age, especially when compared with the findings for school pupils, in which the prevalence of heavy use ranges from 2.2% for illegal substances to 8.2% for legal substances(11,13).

As for variables related to the family context, it was observed that 58.1% of the adolescents lived in step families with the presence of only one of their parents. Before 1988, in Brazil, only families formed through civil marriage (nuclear families) were recognized, with the power all instilled in the masculine figure. However, over time, even with the concept of the nuclear family foremost in society’s imagination, different family structures appeared and family is now defined as any arrangement in which one of the parents lives with their offspring(15).

Thus, the literature shows that there is a relationship between the parents’ conjugal situation and drug use, such as the study conducted among school pupils investigating factors associated with drug use, which found that reported PS use in adolescents whose parents were separated was more than 50% higher than in adolescents who lived with both parents(5). In Curitiba, PR, research conducted with adolescents who had been hospitalized due to alcohol and other drug use found that 59.1% lived in broken homes due to separation or death or did not know one of their parents(7).

Although this study found a predominance of adolescents living in step families or other family arrangements, 52.7% reported a satisfactory home life, in line with data from other studies in which the majority of adolescents report good or very good relationships with both parents(2,5,7). It is, however, noteworthy that 39.2% of the adolescents has unsatisfactory/conflictive relationships, as this type of family relationship is a risk factor for PS use(9,16).

Stress factors such as divorce, remarriage and conflict may initially produce difficulties in the parent-child relationship, however, if the family members manage to establish an affectionate and caring environment, these conflicts can eventually strengthen ties and lead to maturity(15).

In this study, the adolescents report having satisfactory relationships with other relatives, such as grandmothers, aunts and cousins. In almost all cases, there was a female figure, reaffirming the fact that the closest family figure connected to the care is a woman(17).

Analysis of the type of relationship variables also shows a predominance of reported difficulties with father figures. Other studies of this population were not available to compare this data, but a study of high school pupils showed a stronger relationship with the maternal figure compared to with the paternal figure(2). Another study of adolescents showed that among those who reported bad or very bad relationships with the father or mother, drug consumption was significantly higher than among those who reported their relationship with their parents to be good or very good(5).

The quality of relationship between parents and children, then, influences how the adolescent will experience and cope with the insecurities of this stage. By establishing rules and setting boundaries, the family strengthens means for acting correctly, taking on responsibility towards other family members and society regarding choices and actions(16).

In the findings of the present study, more than 70% of the adolescents had a family member who used some kind of PS, in contrast to data presented in other studies, as PS use/abuse by family members was significantly lower in the populations investigated (51.7%; 34.3%)(2,11). It is, however, similar to studies that cite the father figure being the most prevalent family member using drugs(5,11).

It was observed that 40.5% of the adolescents had a relationship with a family member who used PS, this forming part of the environment in which they lived. It is known that parents are responsible for providing role models to be followed by their children and PS use/abuse by those close to them may encourage the adolescents to use(16). A study of school pupils investigating risk factors for PS use showed a significant association between drug use and the presence of someone in the household using alcohol or other drugs excessively(5).

Thus, by unsatisfactorily playing the role of educator, the family may contribute to the children experimenting with or using/abusing psychoactive substances, as the family is the first source of socialization and of the majority of health beliefs and behavior(18).

This study, conducted in the CAPS ad in the State of Mato Grosso, can diagnose the family context of adolescent PS users, mainly because there have been no similar studies in this state. However, it should be noted that the records in the documents studied were not systematized, limiting access to other relevant information.

Conclusions

The findings of this study show socio-demographic characteristics of adolescents undergoing treatment in the CAPS ad and the most commonly used PS that are in line with the findings of other studies. As for the family context, despite the predominance of adolescents living in step families, family relationships were satisfactory and, when difficulties were mentioned, those with the father figure predominated. PS use among family members was in evidence, with the father being the relative most often mentioned.

As the family context can function as both a protection and risk factor in adolescent involvement with PS use/abuse, the importance of evaluating this in the treatment process needs to be understood in nursing and by the inter-disciplinary team, promoting relevant information for comprehensive care, including users and their families, reflecting directly on the effectiveness of care.

References

1. Osório LC. Casais e famílias: uma visão contemporânea. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2002. p. 13–46. [ Links ]

2. Garcia JJ, Pillon SC, Santos M A. Relations between family context and substance abuse in high school adolescents. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2011;19(spe):753-61. [ Links ]

3. Raupp L, Milnitsky-Sapiro C. Reflexões sobre concepções e práticas contemporâneas das políticas públicas para adolescentes: o caso da drogadição. Saúde Soc. 2005;14(2):60-8. [ Links ]

4. Carlini EA, Galduróz JE, Noto AR, Nappo SA. I levantamento domiciliar sobre uso de drogas no Brasil. Estudo envolvendo as 107 maiores cidades do país – 2001. Secretaria Nacional Anti-Drogas (SENAD) e Centro Brasileiro de Informações sobre Drogas Psicotrópicas (CEBRID). São Paulo: Cromosste Gráfica e Editora; 2002. [ Links ]

5. Tavares BF, Béria JU, Lima MS. Fatores associados ao uso de drogas entre adolescentes escolares. Rev Saúde Pública. 2004;38(6):787-96. [ Links ]

6. Schenker M, Minayo MCS. A importância da família no tratamento do uso abusivo de drogas: uma revisão da literatura. Cad Saúde Pública. 2004;20(3):649-59. [ Links ]

7. Alves R, Kossobudzky LA. Caracterização dos adolescentes internados por álcool e outras drogas na cidade de Curitiba. Interação Psicol. 2002;6(1):65-79. [ Links ]

8. Bahls FRC, Ingbermann YK. Desenvolvimento escolar e abuso de drogas na adolescência. Estudos Psicol. 2005;22(4):395-402. [ Links ]

9. Dietz G, Santos CG, Hidebrandt LM, Leite MT. As relações interpessoais e o consumo de drogas por adolescentes. SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool e Drog. 2011;7(2):85-91. [ Links ]

10. Fernandes S, Ferigolo M, Benchaya MC, Pierozan PS, Moreira TC, Santos VS et al. Cannabis abuse and dependency: differences between men and women and readiness to behavior change among users seeking treatment. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul. 2010;32(3):80-5. [ Links ]

11. Costa COM, Alves MVQM, Santos CAdeST, Carvalho RC de, Souza KEP, Sousa HL. Experimentação e uso regular de bebidas alcoólicas, cigarros e outras substâncias psicoativas na adolescência. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2007;12(5):1143-54. [ Links ]

12. Horta RL, Horta BL, Pinheiro RT, Morales B, Strey MN. Tabaco, álcool e outras drogas entre adolescentes em Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil: uma perspectiva de gênero. Cad. Saúde Pública. 2007;23(4):775-83. [ Links ]

13. Teixeira AF, Aliane PP, Ribeiro LC, Ronzani TM. Uso de substâncias psicoativas entre estudantes de Goianá, MG. Estudos Psicol. 2009;14(1):51-7. [ Links ]

14. Brusamarello T, Sureki M, Borrile D, Roehrs H, Maftum MA. Consumo de drogas: concepções de familiares de estudantes em idade escolar. SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. [Internet]. fev 2008 [acesso 24 ago 2012]; 4(1): Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.revistasusp.sibi.usp.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S180669762008000100004&lng=en. [ Links ]

15. Rapizo R. Possíveis conexões entre a ocorrência do divórcio e o uso de drogas por adolescentes nas famílias: uma reflexão inicial. In: Silva EA, Micheli D. Adolescência uso e abuso de drogas: uma visão integrativa. São Paulo: Editora FAP-Unifesp; 2011. [ Links ]

16. Pratta EMM, Sanots MA. Reflexões sobre as relações entre drogadição, adolescência e família: um estudo bibliográfico. Estudos Psicol. 2006;11(3):315-22. [ Links ]

17. Gonçalves JRL, Galera SA. F. Assistência ao familiar cuidador em convívio com o alcoolista, por meio da técnica de solução de problemas. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2010;18(Spec):543-9. [ Links ]

18. Schenker M, Minayo MCS. A implicação da família no uso abusivo de drogas: uma revisão crítica. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2003;8(1):299-306. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence

Correspondence

Samira Reschetti Marcon

Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso

Avenida Fernando Correa da Costa, s/n

Bairro: Boa Esperança

CEP: 78060-900, Cuiabá, MT, Brasil

Received: July 24th 2013

Accepted: Mar. 3rd 2015