SMAD. Revista eletrônica saúde mental álcool e drogas

ISSN 1806-6976

SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. (Ed. port.) vol.11 no.3 Ribeirão Preto set. 2015

https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v11i3p129-135

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

DOI: 10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v11i3p129-135

Crack users’ perceptions of factors that influence use and addiction

Walkiria da Silva RochaI; Estela Rodrigues Paiva AlvesII; Kay Francis Leal VieiraIII; Khivia Kiss da Silva BarbosaIV; Gerlaine de Oliveira LeiteV; Maria Djair DiasVI

IRN, Health Public Specialist, Hospital do Conde, Cidade do Conde, PB, Brazil

IIDoctoral student, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil

IIIPhD, Professor, Faculdade de Enfermagem Nova Esperança, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. Professor, Centro Universitário de João Pessoa, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil

IVDoctoral student, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. Professor, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Campina Grande, PB, Brazil

VRN

VIPhD, Associate Professor, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to identify factors that influence and facilitate crack use and factors that make it difficult to give up. This was a piece of qualitative research involving 20 crack users in João Pessoa, PB, in 2012. The data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire and analyzed using the Discourse of the Collective Subject technique. Easy access, curiosity, peer pressure and alcohol/marihuana use were all shown to be factors that influenced crack use and made it difficult to give up. It is suggested that the views and actions taken of the phenomenon of drug addiction be broadened and more comprehensive nursing care provided based on the factors uncovered in this study.

Descriptors: Crack Cocaine; Behavior, Addictive; Street Drugs.

Introduction

Mind-altering drugs have long been used and will perhaps continue to be used throughout the whole history of humanity. Whatever the reasons: cultural religious, for recreation or as a way of dealing with problems, to transgress to transcend, as a way of socializing or even a way of isolating oneself, human beings have always had, and continues to have, this contact with drugs (1).

The relationship between the individual and the drug, depending on the context, may or may not be harmless or present risks, but its use may also take on highly dysfunctional patterns causing biological, psychological and social harm. This explains the efforts made to spread basic, reliable information about one of the greatest public health problems that, directly or indirectly, affects every human’s quality of life (1).

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, around 315 million individuals aged between 15 and 64 used illegal substances in 2011. This number represents 6.9% of the world’s adult population. The prevalence of illegal drug use and the number of problem drug users – those with disorders from drug use or addiction – remain stable, that is, they have not fallen which, to some extent, reflects the growing world population and the slight increase in the prevalence of illegal drug use(2).

Among the illegal drugs, crack, a byproduct of cocaine and a potent Central Nervous System (CNS) stimulant, stands out. This is due to the scale of the individual, family and social consequences associated with its use, of concern to the State and to society in general(3).

A study conducted in all 26 Brazilian state capitals and the Federal District revealed that those who used crack and/or similar substances regularly totaled around 370 thousand individuals. These users are seen as a hidden population, difficult to access, representing 35% of all illegal drug users, excluding marihuana, in these municipalities, around a million Brazilians (4).

Drug abuse can stem from multiple factors. No one is born doomed to use them, nor do they become dependent simply through the influence of friends or easily availability through dealing. Thus, there are factors that converge in order to produce the circumstances of abuse (1).

There is an evident interrelationship and interdependence exists between users and the context in which they find themselves. Starting to use crack may involve diverse risk factors, making the individual increasingly vulnerable. Age, beginning to use so-called lighter substances (such as cigarettes and alcohol), curiosity, low self-esteem, the existence of depressive symptoms, a need for new challenges and emotions, not being religious, lack of information on the risks of illegal drugs and drug consumption within the family environment, are all factors that can make the individual more susceptible to using illegal drugs. Thinking about this web of vulnerabilities and socio-cultural determinants related to drug use, in an admittedly broad society, makes this phenomenon more complicated to approach (3,5-6).

Being an extremely complex topic, crack use requires inter-sectorial and inter-disciplinary intervention, widening the scope of actions and especially the view taken of the phenomenon of drug addiction, from the perspective of ensuring appropriate care given the demands that end up affecting the personal, emotional and professional spheres, leading to the marginalization of not only the user but also their family and those around them.

Thus, the understanding of what makes people use crack needs to be widened, despite the all the harm this substance can cause. The following guiding question was therefore drawn up: what are the factors that make crack difficult to give up? The aim of this study, then, was to identify the factors influencing the use and abandonment of crack in users in a psychiatric hospital.

Material and Methods

This is an exploratory cross-sectional study with a qualitative approach, conducted in a public psychiatric hospital, a reference for treating drug addicts, which also treats private patients, located in João Pessoa, PB. The investigation was conducted in October 2012.

The study population consisted of 20 male drug users, patients undergoing treatment in the above mentioned institution. The sample was selected based on the following inclusion criteria: being ages 18 or over and using crack as the drug of choice.

A semi-structured form was used to collect empirical data, including objective questions to characterize the subject, and subjective questions referring to the proposed objectives, namely: what influenced you to use crack? Have you thought about giving up? What factors influence or influenced this decision? What factors do you believe make it difficult to give up crack?

The person responsible for the sector treating the crack users was first contacted and a meeting arranged with them and with the health care team in order to explain the purpose of the research and how the data would be collected. The users to participate were identified with the support of one of the nursing technicians and medical records analyzed to identify those who used crack as their drug of choice. Before the interviews took place, there was a group was organized to spread information and for the interviewer to get closer to the participants.

The interviews were conducted in the mornings, in a private room, enabling the participants to feel at ease expressing themselves freely on the topic in question. The morning period was chosen so as not to interrupt visiting hours, which were in the afternoons. Participants were previously informed about the objectives and data collection procedure of the study, ensured by their signing an informed consent form.

The qualitative analysis made use of the Discourse of the Collective Subject (DCS) technique (7). Such analysis represents the collective opinion through a series of discourses, thinking or attitudes to a given topic, present in a particular socio-cultural formation. It also aims to make clearer the expression of a given social representation of a phenomenon experienced (7).

The DCS technique analyzes the groups’ discussions and works according to topics or issues, from which social representations, i.e. methodological figures or operative concepts, are extracted. These are: key expressions, central idea, anchorage or subject’s discourse. Key expressions are continuous or discontinuous segments of discourse that reveal the main discursive content; it’s a type of “discursive-empirical text” of the “truth” of the central ideas. Identifying the central idea means synthesizing the content of these expressions, that is, what they effectively say. And, finally, bringing together key expressions referring to similar or complementary central ideas, in a discourse synthesis which is DCS (7).

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Nursing and Medicine Faculty, Nova Esperança, meeting the guidelines of National Health Council Resolution 196/96, Report nº00/12.

Results and Discussion

Characterizing the crack users

The age of the interviewees varied between 18 and 50, with the majority within the 18 to 24 age group (50%), showing a prevalence of young adults in this study. As for schooling, the majority (65%) had not finished elementary school, 35% had finished high school and 10% had not. Educational and economic conditions influence crack consumption, as well as treatment.

The marital status of 80% of them was single, 15% were separated and 5% were married. Half of them had children (50%). Regarding employment, 30% were on sick leave for treatment and 70% were unemployed, with half of those (50%) having lost their job as a result of drug addiction. Such circumstances lead to unemployment or discontinuous periods of employability.

With regards household income, 70% received the minimum wage (R$ 625.00 in 2013), with only one participant reporting receiving two minimum wages. As for profession, there was a variety of activities: cleaner, mason, baker, broker, fisherman, mechanic, painter, general services, farmer and waiter. These data may be related to the participants’ gender and low levels of schooling.

It was found that 30% had not religion or beliefs, 45% were Catholic and 25% Protestant. As for history of hospitalizations, the data showed that 55% had previously been hospitalized to treat drug addiction, with the number of times varying between one and five times.

When asked about use of legal and illegal drugs, apart from crack, all stated that they also used alcohol, marihuana, loló (a chloroform and ether based narcotic), solvents, Artane and rupinol, especially the first two. Several users mentioned that these substances triggered their crack use, i.e. the compulsion or lack of control leading to crack use occurred after using alcohol or marihuana.

Regarding the presence of family members who use drugs in the same house, 35% stated that this was the case, mainly (85.7%) by the father or siblings. A considerable number of the users had previously been hospitalized and received family visits (55%) during their stay. In this study, 30% of participants reported that they had not managed to give up using the drug, and fewer than half (45%) managed to go without it for three days.

Data related to the proposed objectives

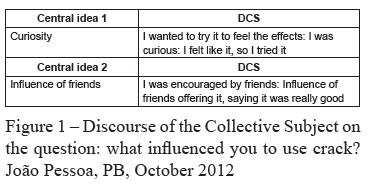

Treating the data lead to three Discourses of the Collective Subject emerging. Through the interviewees’ statements, contained in Figure 1, the DCS referring to influences that lead to using crack can be verified, showing the appearance of to central ideas: curiosity and influence of friends.

There are diverse risk factors for starting to use such psychoactive substances. Curiosity was shown to be a factor that could lead the individual to try the drug, as seen in this study. Other factors have also been identified, in other studies, as factors influencing crack use, including pleasure, family conflict, going through unpleasant situations, existence of the implicit culture of drug use, conflicts and violence, misinformation and lack of knowledge about drugs. Friends’ influence was also seen as a factor leading to crack use. Peer pressure is quite decisive, whether in the context of the family or in the context of sociability outside the family, involving friends and acquaintances (3,8).

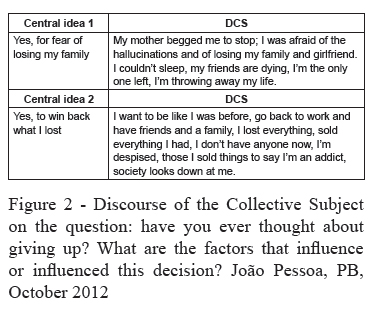

Before being asked about factors that can make it difficult to give up crack, the users were asked whether they had ever thought about stopping using crack and, if so, what lead them to want to give up, as shown in Figure 2. Two central ideas also arose from these questions, concerning fear of losing their family and the desire to win back what they had lost through drug use.

The risk of losing, or the actual loss, of family and even social ties brings great suffering, a fact observed in the interviewees’ emotional statements. Through these comments, it is possible to perceive just how much the family plays a role in seeking a way out, seeking treatment, or even as a support to face the difficult struggle against the urge to consume crack, a fact that has also been observed in other studies (3,6,9).

Authors(6) have shown that unconditional family support strengthens the user to face the negative effects of crack use and the possibility of choosing to give up the substance. Another significant factor in this family context is to perceive the suffering or illness of a relative because of the addiction. Users, on becoming aware of such suffering, cannot bear it and seek treatment. They add that such use should only harm themselves, not cause concern and suffering for their family (6).

Loneliness troubles them greatly, and they become desperate when they feel they are losing family ties. This context is surrounded by the feelings that their relatives no longer respect them, let alone believe in their current choices or promises of abstinence. Breaking emotional ties is also present in this context of loss. Thus, when the users perceive that they can recover their family ties, their motivation to get treated becomes evident and, when the family manages to participate effectively in this treatment, the path to abstinence becomes less painful. Having family with them at this difficult time is a decisive factor in the evolution of the users’ treatment (6).

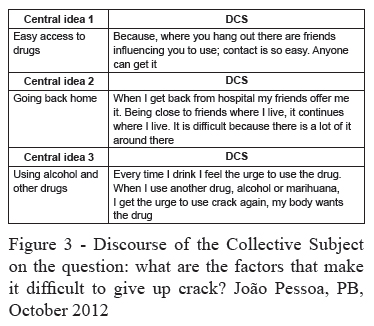

The question concerning factors that make it difficult to give up using crack revealed the most central ideas. Easy access to the drug, going back home and using alcohol or other drugs were the central ideas that appeared, as shown in Figure 3.

The data found are in line with the literature, as ease of access is explained by the fact that the drug is sold very close to their home. This ease may result in the lack of success in attempts to give up, triggering relapses and demotivation to try and stay abstinent (10). It is worth noting that tackling drug dealing makes immediate access more difficult, giving the user the opportunity to choose between use and abstinence and thus having greater chances of opting for an alternative(11).

Breaking free of crack is far from easy, ex-users need continuous psychological support to avoid situations which could lead to them relapsing into drug use. The battle can only be deemed won after at least six years of abstinence, the lure of the drug is strong, access is easy and dealers tend to bombard customers, the drug is cheap and friends are often users too. It is not uncommon for the subject, determined to break the cycle, to be obliged to move job, school, home and often city (12).

The data found show that the use of other substances can also lead to individuals relapsing into using crack, making it difficult to abandon the addiction and recover. These results are in line with the literature, showing that using multiple drugs creates a worse situation in the user’s life as, in addition to becoming addicted to more than one substance, this habit makes recovery difficult and is one of the main causes of behavioral disorders (13-15).

Final Considerations

Curiosity and the influence of others were shown to be the main factors influencing crack use. Ease of access, using alcohol and marihuana and living in social environments in which drugs are consumed also make individuals more vulnerable to crack use and make giving up more difficult. However, the feeling of wanting to recover what has been lost through drug use, fear of death and of losing family ties and the desire to be once again accepted by society were shown to be the initial framework for giving up the vice.

Considering the importance of this topic, it is hoped that the issues raised in this study will be examined in more depth in future studies, contributing to new debates on the topic, as drug addiction is a chronic disease, with a difficult recovery. Moreover, through the results of this study, it is hoped that health care, especially nursing staff, given their closeness to the client and their role in health educational activities, may provide the best quality and most comprehensive care possible, taking into consideration the factors outlined here that influence crack use and make it difficult to give up.

References

1. Ministério da Justiça (BR). Secretaria Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas. Prevenção ao uso indevido de drogas: Capacitação para Conselheiros e Lideranças Comunitárias. 4. ed. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Justiça; 2011. [ Links ]

2. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2013. New York (NY): United Nations; 2013. 151 p. [ Links ]

3. Selleghim MR, Oliveira MLF. Influência do ambiente familiar no consumo de crack em usuários. Acta Paul Enferm. [Internet] 2013 [acesso 29 jan 2013]; 26(3):263-8. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ape/v26n3/10.pdf [ Links ]

4. Ministério da justiça e da saúde (BR). Estimativa do número de usuários de crack e/ou similares nas capitais do país. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Justiça e da Saúde; 2013. [ Links ]

5. Sodelli M. A compreensão do uso de drogas. In: Angel S, Picazio C, organizadores. Viva Melhor com o Adolescente. São Paulo (SP): Larousse do Brasil; 2005. p. 8-101. [ Links ]

6. Mendonça LOM. “Crack”, o refúgio dos desesperados, à luz do programa nacional de combate as drogas. Revista da SJRJ. [Internet]. 2010 [acesso 15 dez 2012];17(29):289-308. Disponível em: http://www4.jfrj.jus.br/seer/index.php/revista_sjrj/article/viewFile/203/201

7. Lefèvre F, Lefèvre AMC. O Discurso do Sujeito Coletivo: um novo enfoque em pesquisa qualitativa. Caxias do Sul (RS): Educs; 2005. 255 p. [ Links ]

8. Jinez MLJ, Souza JRM, Pillon SC. Uso de drogas e fatores de risco entre estudantes de ensino médio. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. [Internet]. 2009 [acesso 30 jan 2014];17(2):246-52. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v17n2/pt_17.pdf [ Links ]

9. Paiva FS, Ronzani TM. Estilos parentais e consumo de drogas entre adolescentes: revisão sistemática. Psicol Estud. [Internet] 2009 [acesso 30 jan 2014];14(1):177-83. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pe/v14n1/a21v14n1.pdf [ Links ]

10. Amaral RG. Padrão de consumo e evolução para dependência de pacientes internados por uso de crack. [Dissertação de Mestrado em Saúde e comportamento]. Pelotas: Universidade Católica de Pelotas; 2011. 46 p. [ Links ]

11. Pavani RAB, Silva EF, Moraes MS. Avaliação da informação sobre drogas e sua relação com o consumo de substâncias entre escolares. Rev Bras Epidemiol. [Internet]. 2009 [acesso 15 dez 2012];12(2):204-16. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepid/v12n2/10.pdf [ Links ]

12. Aratangy LR. Doces Venenos: Conversar e Desconversar sobre drogas. São Paulo (SP): Editora Olho D’Água; 2009. 186p.

13. Oliveira LG, Nappo SA. Caracterização da cultura de crack na cidade de São Paulo: padrão de uso controlado. Rev Saúde Pública. [Internet]. 2008 [acesso 20 jan 2014];42(4):664-71. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v42n4/6645.pdf [ Links ]

14. Oliveira LG, Nappo SA. Crack na cidade de São Paulo: acessibilidade, estratégias de mercado e formas de uso. Rev Psiquiatr Clín. [Internet]. 2008 [acesso 30 jan 2014];35(6):212-8. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rpc/v35n6/v35n5a02.pdf [ Links ]

15. Carvalho MDA, Silva HO, Rodrigues LV. Perfil epidemiológico dos usuários da rede de saúde mental do município de Iguatu, CE. SMAD, Rev Eletrônica Saúde Mental Alcool Drog. [Internet]. 2010 [acesso 27 fev 2014];6(2):337-49. Disponível em: http://www2.eerp.usp.br/RESMAD/artigos/SMADv6n2a7.pdf [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence

Correspondence

Estela Rodrigues Paiva Alves

Rua Edvaldo Bezerra Cavalcanti Pinho, 320, apto. 202

Bairro: Cabo Branco

CEP: 58045-270, João Pessoa, PB, Brasil

E-mail: rodrigues.estela@gmail.com

Received: Mar. 8th 2014

Accepted: Feb. 3rd 2015