SMAD. Revista eletrônica saúde mental álcool e drogas

ISSN 1806-6976

SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. (Ed. port.) vol.11 no.4 Ribeirão Preto dez. 2015

https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v11i4p181-189

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

DOI: 10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v11i4p181-189

The hosting of crack users at a Psycho-Social Care Center: the meanings attributed by workers

Acogimiento a los usuarios de crack de un Centro de Atención Psicosocial: los sentidos atribuidos por los trabajadores

Sinara de Lima SouzaI; Luzimara Gomes MeloII

IPhD, Adjunct Professor, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Feira de Santana, BA, Brazil

IIRN, student, Programa de Residência Multiprofissional em Saúde da Família, Fundação Estatal de Saúde da Família (FESF-SUS) and Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Salvador, BA, Brazil

ABSTRACT

The objectives of this study were to understand the meanings attributed by workers in relation to the hosting of crack users at CAPS ad (Centro de Atenção Psicossocial) in the interior of Bahia, and to identify what actions workers developed in relation to this hosting. The study is characterized by its qualitative, exploratory and descriptive approach. Data collection was performed using semi-structured interviews and participant observation. The technique of thematic content analysis was used, from which two categories emerged. We conclude that, even though some workers were confused with the screening process, they recognized the importance of qualified listening, problem-solving, and humanization, based on the principle of SUS equity, and aimed at recognizing demands and establishing therapeutic relationships without discrimination or bias.

Descriptors: User Embracement; Mental Health; Crack Cocaine.

RESUMEN

Los objetivos de este estudio fueron comprender los sentidos atribuidos por los trabajadores con relación al acogimiento a los usuarios de crack atendidos en un CAPS ad del interior del estado de Bahia e identificar cuales las acciones de acogimiento desarrolladas por esos trabajadores. Estudio cualitativo, exploratorio y descriptivo. Los datos fueron recolectados a través de un guión de entrevista semiestructurada y observación participante. La técnica de análisis de contenido del tipo temático fue utilizado, revelando dos categorías. Se concluye que, aunque algunos trabajadores confundan con el proceso de tamizaje, admiten la importancia de escucha cualificada, resolutiva, humanizada, basada en el principio del SUS de la equidad, visando al reconocimiento de las demandas, estableciendo vínculos terapéuticos, sin discriminación o perjuicio.

Descriptores: Acogimiento; Salud Mental; Cocaína Crack.

Introduction

The National Policy of Humanization of Care and Management in the Unified Health-HumanizeSUS System (PNH), was created in order to reverse some persisting challenges regarding the implementation of the public health system, especially with regard to the unpreparedness of professionals and other workers to deal with the size of the subjectivity that permeates the entire health practice. Because it is a policy, the PNH has directives that express its general guidelines and, of these guidelines, hosting is emerging as one of the principle ones(1).

According to HumanizeSUS – the base document for managers and SUS workers(1), and launched by the Ministry of Health (MOH) - hosting is a process of production and health promotion practices, taking into account qualified hearing to enable analysis of demand to meet needs, from the moment the service is sought to its output. This ensures comprehensive, resolute and responsible care, and developed in coordination with internal and external networks, i.e. the very same interdisciplinary teams and other services that can continue care when needed.

The hosting, as an operational guideline, involves reversing the organizational logic and functioning of services, and starting from the principles of universal access, the resolution of health problems, the reorganization of work processes which will involve the attention of all staff, and the qualification of the relationship between the worker and the user in search of solidarity, humanity and citizenship. In addition, with respect to the way it works toward health, hosting reveals new ways to operate, taking into account assistance which is focused on the user, and not the disease(2).

This is a process of transformation of assistance from the biomedical model, that exists as the center of production in the realms of health and disease, to one that operates from the user, with the guiding principle that the host must also be covered by workers who work in the mental health field. And in Brazil, starting from Psychiatric Reform, it was proposed a more equitable approach be adopted. More comprehensive and community-based, the bearer of the mental disorder was once seen as a being who should be excluded from social life and thrown in psychiatric hospitals, often without the necessary support to treat all patients, due to overcrowding.

The use / abuse of psychoactive substances (SPA) is also a component of mental health policy. Historically, the care directed to drug users was returning to actions based on exclusion and achievement of abstinence. However, the anti-repressor model had no effect and, in addition, the issues with drugs were associated as well with more marginal practices being treated as police cases. Even being between the Psycho-social Care Center’s (CAPS) classifications - proposed by administrative rule - CAPS are places of welcome, care, support, prevention and coping issues related to drugs, and have begun to gain more prominence in the mental health arena after being established the Community Care Program Integrated with Alcohol and Other Drugs User by Ministerial Decree nº816 of 30 April 2002(3).

The use of SPA has intensified increasingly and is becoming an important public health problem that requires investment in health policies to treat users warmly, considerately, without prejudice, by breaking paradigms between the association of the use / abuse and its marginalization, and without being treated as a police case. Thus, CAPS are important devices within that process that emerge as enablers of a treatment no longer centered on exclusion and withdrawal, since treating the addict requires certain specifics, besides having to overcome old dilemmas of providing hosting based on the policies of humanization.

In a survey conducted in the Virtual Health Library (VHL), with the hosting and CAPS descriptors, of the 27 articles found in the search portal, 20 contemplated the issue of hosting in CAPS and only one presented a field of study CAPS ad, or involve other CAPS in the study. Given the above, it can be inferred that there is lack of studies concerned with what the professionals do in relation to the hosting for this clientele, what their values and beliefs are, and how they act at the moment of receiving this type of user. Because on the one hand, there is the idea that drugs are linked to situations of illegality, which can hinder the approach of users to health care services, and on the other, there is the way work is organized and how unity and staff are ready to serve them.

Besides these issues, the awareness of this issue also arose from field trials in the period in which the author, here, participated as a fellow at the Mental PET-Health, Alcohol, Crack and Other Drugs, taking the opportunity to reflect on how to treat and accommodate drug users. Before joining the program I did not know this reality. From this experience, it de-mystified these concepts in relation to how to treat people, and there was the recognition that addiction is a chronic disease that requires a humanized and welcoming treatment, with actions involving a multidisciplinary team. From this, the following question arose: what are the meanings attributed by the workers in relation to the hosting to crack users at CAPS ad in the interior of Bahia?

This study aimed to understand the meanings attributed by the workers in relation to the hosting of crack users attending the CAPS ad in the interior of Bahia, and to identify what actions of commitment are undertaken by workers CAPS ad.

Methodology

This research is qualitative, exploratory and descriptive. It was held at CAPS ad in Feira de Santana, Bahia. The service is intended for people with mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol abuse and other drugs from the age of fifteen, providing treatment and support to users and their family through individual consultations, groups and workshops, medication, as well as educating the public about the harms and risks associated with the use / abuse of psychoactive substances.

Study participants were workers in the CAPS ad who had been working for more than six months, because it is understood that hosting is practiced from the time the professional begins work in the service. However, for the recognition of their field subjects were required with experience of engagement with users and the dynamics of the service. The professional category has not been defined to include work by CAPS ad, that is, from the perspective of an interdisciplinary team to care for users. Thus, currently, the team consists of 21 employees, of which 18 agreed to participate in the study, however, just 17 were analyzed because interview one (Ent.1) was used as pre-test. Therefore, in this study, there were seventeen participants.

For the data collection, semi-structured interviews were used to obtain primary or subjective information. The technique of participant observation was also used. For this, instruments were used as a road map for participant observation and the field diary. Data was analyzed using the thematic content analysis technique.

The research was based upon what comprises Resolution 466 of December 12, 2012, from the National Health Council, which has regulatory guidelines and standards for research involving human beings(4). To this end, authorization was sought from the Coordination of Permanent Education Municipal Secretary of Health. The project was registered on the Platform Brazil and submitted to the Ethics Committee of the State University of Feira de Santana. Thus, the data collection for this study was conducted after approval by the Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Interviews were conducted with the various workers who make up the CAPS ad team, being occupational therapists, nurses, psychologists, nursing technicians, social workers, educators, and medical and administrative assistants. Of the total participants analyzed, most were women, corresponding to 14 of the workers*, and three were male. With regard to age, the predominant age group was between 31 and 40 years, with eight of those interviewed falling into that category. The majority of the educational level, totaling eleven workers, was at college level, and four of these had gone on to graduate. Only three had training in the mental health field and one was attending a post-graduate course.

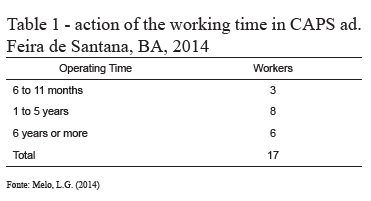

Despite the high turnover, which is part of the health scenario in the city, most of the interviewees had been working in CAPS ad for more than one year, as shown in the table below:

The CAPS ad scenario has been the acting Education Program for Working for Health since April 2011 and currently has ten fellows and a volunteer, five mentors and a volunteer mentor, and two tutors, distributed between PROPET - Mental Health and the PET - Health Networks. According to the interviews, of the total interviewees, four are members of this program as mentors, and one as a volunteer mentor.

The various feelings attributed to the hosting of crack users

This category discusses the feelings attributed to the hosting of crack users by health workers in the CAPS ad. Note that these feelings reveal that, for some workers, this technology constitutes something timely, while for others, it evidenced the recognition that this technology pervades all stages of the encounter between worker / user.

Hosting as an act of receiving and triage

In most of the analyzed discourses, the female workers revealed hosting as the act of receiving the user in the service.

Hosting is subjective, in which you receive someone and create empathy for that person, and we look to give this the word ‘hosting’, but it’s the necessary acceptance of his needs for his suffering at the moment (Int.10).

[...] So I think this is hosting, and it’s good to hear others, to do qualified listening, it’s the best, right? And along with that trace the outline of the project so he can go and run his treatment, from that day (Int.18).

From the discourses we can infer that workers attach to hosting the act of receiving the user, this being linked to something subjective that goes beyond only one action. The word ‘receive’ appears in many interviews and the meanings they ascribe go beyond just receiving, but also to be ‘available’ so that it becomes a moment of encounter that enables them to hear, listen, empathize, acting as the sensitive professional for such action.

It is observed in various discourses that even the workers who recognize the hosting as a moment of listening, creating empathy and a subjective dimension, ultimately confuse it with the screening process and the act of receiving ends up being associated with that of screening. As can be seen below.

Actually screening is done, right? You have to know what it is that he is feeling at the moment, what he wants, his desire and that’s it (Int.11).

For me, hosting is when the user begins searching for the institution. So the moment he seeks it out, the person on duty on that day will host him [...] (Int.17).

[...] It’s the first time that the patient has with the employees of the institution, right? (Int.8).

According to the unit’s routine, every day of the week a top-level professional is scheduled to perform the "hosting", which is the time the professional analyzes the demand. Therefore it was noticeable, in the words of some participants, that the meaning attributed to the hosting was confused with the screening process. These two differ, since triage involves a one-off action and a step in the user process of joining the service, and hosting permeates every moment of therapeutics and health care(5-6).

Hosting as the typical technology of the meeting

The Ministry of Health in its manual on hosting in health production practices, considers the hosting as a technology of meeting, that facilitates an affective regime that enhances the health production processes(5). This approach of hosting, as a moment of encounter, in which the employee receives the user, was evident in the speech below.

Hosting is an act of meeting, right? It’s making yourself available to the other, to listen, to be sensitive to the suffering and feelings of others, in order to help, to be ready, to try to solve other’s problems (Int.5).

The hosting is a proposal for an improvement in relations between workers and users, taking shape in the meeting of these, through a joint enterprise made up of listening activities, identifying problems, demand processing and a search for resolutions(7-8). Therefore, listening appears as a crucial point for the realization of the hosting. In this study, we could see that in the discourse of the majority of workers listening appears as the main aspect for the hosting.

[...] It has a distinctive type of listening too, right? And to hear a lot, to hear is more patient than talking. [...] Because often you start off for the activities or somewhere, and this patient it will not go there because it is not his desire (Int.3).

Hosting is the different way of listening, it is hearing the patient in the first instance. [...] Hosting is, to hear, to listen. [...] The differentiated listening, unhurried, without delay, because it does not help us to do the hosting in a hurry, and do an excellence work (Int.15).

Another component of hosting that emerged from the discourse of the workers concerned the view of this as a condition in which the user sees without prejudice, thus constituting a different outlook for the crack users.

[...] So I think it’s that you are there, willing to listen, willing to stand in front of his story, regardless of what you have lived, regardless of what you believe, right? Leaving aside, really, prejudice, leaving aside the trial, right? (Int.14).

The CAPS are environments that awaken in the users the feeling of belonging to a community, a feeling that it was lost, because, by order of society, they carry the stigma of crazy or on drugs(9). On this new way to assist these clients, in Int.4 it was said that:

The crack user, as well as other drugs, already suffers from discrimination [...] and here when he arrives, he is welcome, because the unit exists to provide this service (Ent.4).

Another aspect that emerged from the discourse of three participants was the hosting as something continuous that, according to the Ministry of Health, is a process of production and promotion of health, in which the worker and staff are responsible for the user from his arrival until his exit(1). This is quite explicit within the discourse of Int.2 when hosting is defined as follows:

Hosting is when you receive and welcome the patient from the moment he arrives at the unit for the first time, throughout his stay until he leaves, until he is, so to speak, discharged. That is, listen to the patient, so he is able to understand, so you can solve their demand and make necessary referrals, either inside the unit to other professionals, or to other health facilities outside the CAPS ad (Int.2).

In addition, the understanding that listening and understanding the demand is something fundamental to resolution also appears in the discourse of Int.2, which mentions that you need to understand to solve their demands. Similarly, such placement also emerged in the discourses of other participants. Thus, it is perceived that this understanding is a crucial point, as hosting is not only listening, but in the use of this technology as a guide for a terminating treatment.

The operation of the hosting of crack users in the everyday life of workers from CAPS ad

The hosting constitutes an operational guideline aimed at the enhancement of the individual’s subjective dimension, as well as the understanding that this has socio-cultural aspects that also need to be considered, leading to an equanimous and integral approach.

During the analysis of interviews and field observations, it was found that workers in the CAPS ad are concerned to see the user in their entirety, not just the illness / addiction. Thus, it can be observed in the interviewee discourse below.

[...] Looking at the subject, the relationship he has with the drug, without making generalizations or reductionisms, in order to see the subject and the issues he brings with him, his family relations, the bio-psychosocial and even spiritual, it all plays a role. Somehow it is all associated with the use (Int.16).

In this context, having recognized the bio-psychosocial and cultural aspects, a worker also recognized the importance of family relationships for the treatment of crack users.

[...] Most of the time, these patients are already living in the street. So sometimes, we search, and what can make the difference is precisely that, so sometimes you search for contact with the family in order to re-integrate this patient again the family (Int.2).

It emerged in the discourses of most participants that the hosting of crack users should be done in the same way that it is with other users seeking CAPS ad. However, two participants stated that there is specificity, as can be seen in the discourses of Int.10 and Int.11.

The hosting of crack users has specificity because the crack user is very restless if he comes in crisis, he gets very restless. So do not demand too much of his attention, right, listen to him and be present. The presence of the professional with the client, the user, is important (Int.10).

[...] I think it should be a different type of hosting [...] to support, because alone they often do not continue. They are patients, by the fact I perceive them to have a hard time getting out of dependency and who find it difficult to maintain treatment, because of the addiction, dependence is very large, very physical too [...] (Int.16).

Another aspect, with respect to the hosting of crack users that appears in the statements of the participants, as a complicating element to the hosting is how that user reaches the service, because there were several reports of restlessness, aggressiveness and user irritability in that type of psychoactive substance user, as in the following lines.

[...] So you have to be sensitive and, perhaps, with a little more availability in the sense that sometimes they are more resistant, right? [...] This is common, so you must be available to listen, to understand that sometimes that irritability, that aggressiveness, is not focused, it’s not for you, it would be for anyone who had been there then and near him [...] (Int.5).

[...] Listening, trying to talk, sometimes when he’s very angry, trying to take the situation in a bit of a lighter direction, more availability, even trying to make a game for him between this game, he can relax a little bit, become less angry, then bring it to reality, to say, "oh here we go, I can try to help you, you just have to want it," right? (Int.5).

In addition, hosting arises in times of a crisis, which does not constitute a bad situation that needs to be blocked and controlled more quickly, and should not be seen only as worsening of psychiatric symptoms, but a need to waken in the worker an attitude of support, to enhance the individual as a human being and not just as sick, respecting their time, their individuality and uniqueness, performing a therapeutic listening without making moral judgments, just to listen(10). In line with this, in Int.10 the respondent says: "[...] the crack user, he is very restless if he comes in crisis, he gets very restless. So do not demand too much of his attention, right? Hear him, and be present", thus recognizing the importance of listening in attendance in crisis.

Discussion

To attribute to hosting a one-off action is revealed as a complicating factor in that the hosting comes to be conducted in accordance with the proposal of the National Policy of Humanization, which aims for integral and effective attention based on recognition of subjective dimensions with regard to dealing with and treating users.

Within the study there was evidence of a linking of screening with hosting, because "screening was applied at the same time and thus took the name of hosting, but without thereby significantly changing the practices, not allowing the space for speech, not reorganizing the care network, and not investing in bonds with users "(11). It was possible to relate the association of the hosting with screening in this study due to the fact that the first studied ‘attending’ held at CAPS ad was referred to as hosting, which lead to an associative confusion between these two terms, causing the workers to understand the two synonymously.

The triage, or screening "is constituted at the time of receiving the mental patients and works to valorize the content of their speech in order to identify the profile of the person to be served"(12). This leads to the inference that the hosting is contained in the reception and screening, however, goes beyond these moments, in that it must permeate every moment of interaction between staff and users.

One can see that there is concern on the part of workers to rescue the family life that once was lost, due to the use / abuse of psychoactive substances, as family ties are broken or weakened due to drug addiction, and the recovery context is favored when permeated by a set of support such as family, friends and network groups. Also, one must take into account the importance of providing support to the social network in which users of psychoactive substances are inserted, in this case, the family, in order to modify the vulnerable structure due to the addictive process(9).

Is worth noting that, in the field in which this study was conducted, there is the family group, which supports family understanding, so that the issue of drugs is not limited to those treating the user. It pervades bio-psychosocial issues, taking into account the importance of preparing the family to receive this user, whose ties were lost. Thus, this initiative reveals the sensitivity of staff to meet the demands not only of users but also of the host family to which patients belong.

By stating that the hosting of crack users has specificity and should be distinguished from hosting provided to others, it can be inferred that this hosting is found to be guided on the principle of equity SUS, this being understood as a way of addressing inequalities to ensure that people with deficiencies and different needs are addressed differently to achieve equality through the redistribution of service offerings, the prioritizing social groups, whose living conditions are precarious, and emphasize specific actions to those who present different risks of illness and death for certain problems(13).

The crack, which as a drug lasts for a very short time, around five minutes, causes the user to re-use it more frequently, leading to dependency much more quickly, and the development of the crack habit, or , an uncontrollable desire or compulsion to feel the effects that the drug causes. With this, the user starts to increase consumption, which leads him to develop violent behavior, irritability, tremors and bizarre attitudes due to the onset of paranoia, which causes aggressive situations, delusions and hallucinations(14).

Given the above, and from the analysis of the interviews, it was possible to see that the workers recognize that the understanding of the effects that this substance has on the body is also important for the realization of a hosting that works to establish links and ensure continuity of treatment.

From field observations it was possible to perceive other dimensions involving the studied operation of the hosting in CAPS ad, and which has not been reported in the interviews, such as the deficit of workers to meet the great demand, the physical structure of the unit which functions in a rented house and needs to be adapted to the operation, and the integration between the various workers team, which favors a service able to resolve the needs of its users.

Final Considerations

Psychiatric Reform together with the National Humanization Policy provide important pillars to ensure the realization of care based on the principles of SUS universality, integrality and fairness, with respect to crack users. Thus, hosting these users has been revealed as a new way of operating which aims to recognize the specific health needs of an enlarged clinic, and a humanized look, free from stigma and / or prejudices.

Finally, the study contributes to understanding the meanings attributed to the hosting of crack users and how that occurs during the work process in the CAPS ad studied. However, much remains to be explored with regard to the hosting of this population, and given the paucity of studies in this area, which emphasizes the importance of research that will explore this theme.

In this way, this research demonstrates the relevance of the proposed joint education, service and community, through PET, and certainly contributes to the rethinking of practices in CAPS ad, and for the training of fellows who work in the program. In addition, the disclosure of this study may help in the development and / or improvement of public policies related to crack cocaine users.

References

1. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Núcleo Técnico da Política Nacional de Humanização. HumanizaSUS: documento base para gestores e trabalhadores do SUS. 4. ed. Brasília (DF): MS; 2008. [ Links ]

2. Franco TB, Bueno WS, Merhy EE. O acolhimento e os processos de trabalho em saúde: o caso de Betim, Minas gerais, Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública. 1999;15(2):345-53. [ Links ]

3. Jorge MAS, Alencar PSS, Belmonte P, Reis VLM. Políticas e práticas de saúde mental no Brasil. In: Escola Politécnica de Saúde Joaquim Venâncio (org.). Textos de apoio em políticas de saúde. 2005. p. 207-22. [ Links ]

4. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Resolução nº 466 de 12 de dezembro de 2012 do Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde; 2012. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html. Acesso em: 30 jun. 2013. [ Links ]

5. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Núcleo Técnico da Política Nacional de Humanização. Acolhimento nas práticas de produção de saúde. 2. ed. 5. reimp. Brasília (DF): MS, (Série B. Textos Básicos de Saúde) 2010. [ Links ]

6. Jorge MSB, Pinto DM, Quinderé PHD, Pinto AGA, Sousa FSP, Cavalcante CM. Promoção da saúde mental - Tecnologias do cuidado:vínculo, acolhimento, co-responsabilização e autonomia. Ciênc.saúde colet. 2011;16(7):3051-60. [ Links ]

7. Tesser CD, Poli Neto P, Campos GWS. Acolhimento e (des)medicalização social: um desafio para as equipes de saúde da família. Ciênc.saúde colet. 2010 nov; 15(3): 3615-24. [ Links ]

8. Lopes GVDO, Menezes TMdeO, Miranda AC, Araújo KL, Guimarães ELP. Acolhimento: quando o usuário bate à porta. Rev. Bras Enferm. 2014; 67(1):104-10. [ Links ]

9. Souza J, Kantorski LP, Mielke FB. Vínculos e redes sociais de indivíduos dependentes de substâncias psicoativas sob tratamento em CAPS AD. SMAD, Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Mental Álcool Drog. [online] 2006;2(1):1-17. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/smad/v2n1/v2n1a03.pdf. Acesso em: 29 abr. 2014. [ Links ]

10. Ferigato SH, Campos RTO, Ballarin MLGS. O atendimento à crise em saúde mental: ampliando conceitos. Rev. de Psicologia da UNESP. 2007;6(1):31-44. [ Links ]

11. Araújo AK, Tanaka OY. Avaliação do processo de acolhimento em Saúde Mental na região centro-oeste do município de São Paulo: a relação entre CAPS e UBS em análise. Rev. Interface – Comunic., Saúde, Educ. 2012;16(43):917-28.

12. Oliveira FB, Silva KMD, Silva JCC. Percepção sobre a prática de enfermagem em Centros de Atenção Psicossocial. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. (Online). 2009;30(4):692-9. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rgenf/v30n4/a16v30n4.pdf. Acesso em: 28 jul. 2014. [ Links ]

13. Teixeira C. Os princípios do Sistema Único de Saúde. 2011 jun. Disponível em: http://www.saude.ba.gov.br/pdf/OS_PRINCIPIOS_DO_SUS.pdf. Acesso em: 25 maio 2014. [ Links ]

14. Carlini EA, Nappo SA, Galduróz JCF, Noto AR. Drogas Psicotrópicas – o que são e como agem. Rev. IMES. 2001;(3):9-35. Disponível em: http://www.imesc.sp.gov.br/pdf/artigo%201%20-%20DROGAS%20PSICOTR%C3%93PICAS%20O%20QUE%20S%C3%83O%20E%20COMO%20AGEM.pdf. Acesso em: 25 maio 2014.

Received: Sep. 19th 2014

Accepted: Nov. 5th 2014

Correspondência

Sinara de Lima Souza

Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana

Departamento de Saúde

Avenida Transnordestina, S/N

CEP: 44.036-900 Feira de Santana, BA, Brasil

E-mail: sinaradd@yahoo.com.br