Trivium - Estudos Interdisciplinares

ISSN 2176-4891

Trivium vol.11 no.1 Rio de Janeiro jan./jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18379/2176-4891.2019v1p.9

ARTIGOS TEMÁTICOS

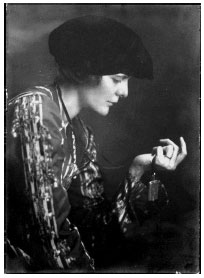

Rewriting psychoanalysis: H.D.'s tribute to Freud

Réécrire la psychanalyse: hommage de H.D. à Freud

Isabelle Alfandary

Philosophe, directrice de programme au Collège international de philosophie, philosophe, Professeur de littérature américaine, Directrice de Recherches, Université Paris-Est-Créteil. Adresse: Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Institut du Monde anglophone, 5 rue de l'Ecole de médecine, 75006 Paris, France. Phone +33 1 40 51 33 08. E-mail: isabelle.alfandary@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article tries to address the ambivalent nature of H.D.'s Tribute to Freud with respect to her literary career. The author's contention is that the American poet in this seminal and hybrid text pursues both a poetic and a personal agenda. Tribute to Freud reads as a book of mourning as well as a book of rebellion, a book of commitment to psychoanalysis as well as of a book of resistance to it.

Keywords: HILDA DOOLITTLE; LITERATURE; PSYCHOANALYSIS.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article examine la relation ambivalente que le livre d'H.D. Pour l'amour de Freud entretient avec le reste de sa carrière littéraire. L'auteur de l'article soutient que le poète américain dans ce texte hybride et seminal poursuit un but tant littéraire que personnel. Pour l'amour de Freud se lit comme un livre de deuil aussi bien qu'un livre de rébellion, un livre d'engagement aussi bien que de résistance vis-à-vis de la psychanalyse.

Palabras clave: HILDA DOOLITTLE; LITTERATURE; PSYCHANALYSE.

In this paper, I would like to address the ambivalent nature of Tribute to Freud, and notably its first chapter entitled "Writing on the Wall" H.D. wrote in London in the autumn of 1944, with no reference to her Vienna notebook of spring 1933, and published in 1945, more than ten years after her first encounter with the father of psychoanalysis. My contention is that in this work H.D. pursues both a poetic and a personal ambivalent agenda, an agenda of love and rebellion, as well as a dialogue with a ghost. Tribute to Freud is a book of memoirs, a book of celebration, and a book of mourning, a mourning of a very particular kind, the mourning of a man, of an analyst, the impossible mourning of an analysis. A work of commitment to psychoanalysis, Tribute to Freud also reads as a book of resistance to psychoanalysis, under the spell of what Freud himself defines as "transference" in his 1937 essay "Analysis terminable and interminable".

H.D.'s relationship with Freud and with psychoanalysis has been addressed by critics such as Susan Friedman:

H.D.'s nonrationalist perspective requires a phenomenological methodology for the assessment of occult influence. The temptation to evaluate her mysticism from a rationalist or psychoanalytic perspective may be great. But to understand how a modernist poet interacted with esoteric tradition and transformed it into art, an examination of how of how she experienced this mythmaking process is more fruitful. (158)

Unlike Friedman and taking up the exact terms that she brushes aside, I would like try and question how a modernist poet transformed her psychoanalytic cure into writing or re-writing. H.D. had read Freud's works intensively and enthusiastically before she ever began her analysis with him: "I begin intensive reading of psychoanalytic journals, books, and study Sigmund Freud" she wrote in 1932, 'There is talk of my possible going to Freud himself in Vienna" (vii). Very early on, she had felt driven to psychoanalysis, both for personal as well as poetic reasons. However, H.D's reason for seeing Freud was less abstract than Susan Friedman tends to suggest ("get his help in translating "the things that happened in [her] life, pictures, real dreams, actual psychic or occult experiences that were superficially at least, outside the province of psychoanalysis", 159), as she clearly states in the Tribute:

And the thing I wanted primarily to fight in the open, was, its cause, and effect, with its inevitable aftermath of neurotic breakdown and related nerve disorders, was driven deeper. With the death-hand swastika chalked on the pavement, leading to the Professor's very door, I must, in all decency, calm as best as I could my personal Phobia, my own little Dragon of war-terror. (94)

The terms of in which she justifies her calling to Freud remarkably denote a staging of the scene of analysis as well as of the self in analysis. The becoming of the self in the Tribute is achieved through a series of literary, biblical, mythological personae, some of which are masculine like Perseus, Moses and Joseph. Norman Holland has convincingly argued that H.D. was able confront the no less mythical figure of Freud whom she calls the "blameless physician", the healing teacher of the gods in Greek mythology, through the wearing of successive masks (485-493).

Resistance to analysis

My contention is that the Tribute and contemporary poetic writings including the Trilogy stem from the resistance to analysis rather than from the healing unraveling of painful associations. In his essay "Analysis terminable, analysis interminable", Freud addresses the clinical issue of the aftermath of transference, namely the remainder of transferential energy after the termination of the cure. In order to do so, he recalls the story of a patient where we can hear a faint and distant echo of H.D's story:

At that time I had taken on the case of a young Russian, a man spoilt by wealth, who had come to Vienna in a state of complete helplessness, accompanied by a private doctor and an attendant.1 In the course of a few years it was possible to give him back a large amount of his independence, to awaken his interest in life and to adjust his relations to the people most important to him. (217)

Freud first believed his patient had been cured for good ("When he left me in the midsummer of 1914, with as little suspicion as the rest of us of what lay so shortly ahead, I believed that his cure was radical and permanent" (217)), but had then to reconsider his diagnosis:

In a footnote added to this patient's case history in 1923, I have already reported that I was mistaken. When, towards the end of the war, he returned to Vienna, a refugee and destitute, I had to help him to master a part of the transference which had not been resolved. This was accomplished in a few months, and I was able to end my footnote with the statement that 'since then the patient has felt normal and has behaved unexceptionably, in spite of the war having robbed him of his home, his possessions, and all his family relationships'. Fifteen years have passed since then without disproving the truth of this verdict; but certain reservations have become necessary. (217-218)

The reason for Freud's mistake lied in his overlooking of what he himself calls "a part of the transference which had not been resolved" (218). At the time H.D. composed the Tribute first chapter "Writing on the Wall", in the autumn of 1944, Freud had been dead for 5 years, yet the book reads as an attempt "to master a part of the transference which had not been resolved" and which haunts H.D.'s relationship to Freud and to psychoanalysis, her poetically fruitful and conflictual mistake of Freudian psychoanalysis.

In the case of his Russian patient, Freud further explains:

But several times during this period his good state of health has been interrupted by attacks of illness which could only be construed as offshoots of his perennial neurosis. Thanks to the skill of one of my pupils, Dr. Ruth Mack Brunswick, a short course of treatment has on each occasion brought these conditions to an end. I hope that Dr. Mack Brunswick herself will shortly report on the circumstances. Some of these attacks were still concerned with residual portions of the transference; and, where this was so, short-lived though they were, they showed a distinctly paranoid character. In other attacks, however, the pathogenic material consisted of pieces of the patient's childhood history, which had not come to light while I was analysing him and which now came away - the comparison is unavoidable - like sutures after an operation, or small fragments of necrotic bone. I have found the history of this patient's recovery scarcely less interesting than that of his illness. (218)

The Tribute can be considered as one of these so-called "attacks" in so far as it is concerned with transferential material woven together with "pieces of the patient's childhood history". To that extent, the Tribute poetically performs a continuation of the cure in the form of a revisitation, of a re-writing. And writing is inseparable from re-writing her works: H.D.'s poetics is constantly engaged with the desire and necessity to re-write, revisit, translate, transfer, re-inscribe, make room for her own mark, her poetic voice and acronym.

As many instances in the text demonstrate, H.D.'s relationship to psychoanalysis is marked by ambivalent feelings, drives, and motivations. Here is one of many developments where H.D. supposedly pays homage to the great man:

In any case (whether or not, the converse is also true), he had opened up, among others, that particular field of the unconscious mind that went to prove that the traits and tendencies of obscure aboriginal tribes, as well as the shape and substance of the rituals of vanished civilizations; were still inherent in the human mind-the human psyche, if you will. But according to his theories the soul existed explicitly, or showed its form and shape in and through the medium of the mind, and the body, as affected by the mind's ecstasies and disorders. About the greater transcendental issues, we never argued. But there was an argument implicit in our very bones. (13)

The concessive clause ("The human psyche, if you will") obviously reads as a marker of conflictuality with one of Freud's key concepts. H.D. would rather resort to the word "soul" that she finds more consonant with her own mystic beliefs. Her reading of Freud relies on a forceful misunderstanding of his rationalist and objective approach of the unconscious: the reality of the Freudian unconscious does not however point to some esoteric, occult transcendental oversoul. The use of the word "medium" in this context may arouse suspicion. Mediation as Freud conceives of it is by no means of a supernatural or supernormal nature. In her Tribute, H.D. chooses to think of her psychoanalytical cure with Freud as an initiation as Susan Friedman argues:

She believed that her initiation into mystical traditions depended fundamentally upon her psychoanalytic séance. As she wrote in Compassionate Friendship: "I had my question and my answers in that period of War II London, but without preliminary work with the Professor, I could never have faced this final stage of the initiation." (158)

The motif of ambivalence can be stylistically and rhythmically traced in H.D.'s text whenever she struggles with Freud, somewhat resists his views and defends him at the very same time. Freud becomes the transferential object of rhetorical, instinctual transactions whereby H.D. promotes, protects, objects to and distinguishes herself from his contentions. In this ambivalence, the so-called transferential love which Freud deemed to be both efficient and fake love is precisely at play.

In the passage quoted above, H.D. deliberately ignores the asymmetrical nature of the analytic relationship when she suggests that the analyst and the analysand's views on transcendental issues were exchanged in the course of a conversation. Here H.D.'s understatement manifests her fierce struggle with the person of the analyst. In his article, Freud concludes "The struggle between physician and patient, between intellect and the forces of instinct, between recognition and the striving for discharge, is fought out almost entirely over the transference-manifestation" ("Dynamics" 322). To that extent, Susan Friedman sounds quite prejudiced when she reflects on "Freud's influence as a collaboration, a dynamic interaction of two whole human beings" (49).

However, the potential archaic violence implicitly carried out by the final metaphor of the bones ("But there was an argument implicit in our very bones") adumbrates what Freud defines in the same 1937 article as "negative transference" whereby the patient addresses the analyst hostile feelings. In an earlier article dated 1912 entitled "The Dynamics of Transference", the psychoanalyst had made it clear that transference is an unavoidable process: "I wish to add that the transference inevitably arises during the analysis and comes to play its well-known part in the treatment" (313). If not all of transference is negative, it is explicitly defined by Freud as the driving force of the cure despite the fact that transference in the course of analysis is "always what seems at first to be only the strongest weapon of the resistance" ("Dynamics" 318). Tribute to Freud alternates moments of what Freud would refer to as "affectionate transference" with moments of "negative transference", whenever hostile feelings, however discreet or dispersed, are perceptible at the surface of the text. I do not mean to reduce the Tribute to a mere clinical material but would like to consider by what means H.D. achieves the re-writing of her cure and opens up on the possibility of going back to writing, to re-write.

In "The Writing on the Wall" H.D. expresses repeated concerns about Freud's after-life:

I cannot compete with her [Marie Bonaparte]. Consciously, I do not feel any desire to do so. But unconsciously, I probably wish to be another equal factor or have equal power of benefiting and protecting the Professor. I am also concerned, though I do not openly admit this, about the Professor's attitude to a future life. One day I was deeply distressed when the Professor spoke to me of his grand-children - what would become of them ? He asked me that, as if the future of his immediate family were the only future to be considered. There was of course the perfectly secured future of his own works, his books. But there was a more imminent, a more immediate future to consider. It worried me to feel that he had no idea - it seemed impossible -- really no idea that he would 'wake up' when he shed the frail locust-husk of his years, and find himself alive" (43).

By manifesting how much she cares for Freud and admires his work, and by becoming protective of him, not only does she compete with the "Princess", but she tries to revert the terms of the therapeutical relationship, literally reciprocating the care she has received. Expressions such as "equal factor" and "equal power" read in reference to Freud. The real competitor is the analyst himself: "So again I can say the Professor was not always right. That is, yes, he was always right in his judgments, but my form of rightness, my intuition, sometimes functioned by the split-second (that makes all the difference in spiritual time-computations) the quicker" (98). H.D.'s exasperation towards Freud's concern about his own family can also be interpreted as a jealous reaction on H.D.'s part. In the Tribute, Freud turns out to be the only object in both the common and analytical sense of the word, an object around which all other objects seem to revolve; or more precisely the only object with respect to H.D. The centrality of the tranferential bond, constitutive of the analytic relationship and the possibility of the cure, based on subjective displacement and the repetition of a former neurotic and possibly traumatic love relationship, is confirmed throughout the Tribute and notably a few lines further down when H.D. writes, "I mean, I felt that to meet him at forty-seven, and to be accepted by him as analysand or student, seemed to crown all my other personal contacts and relationships, justify all the spiral-like meanderings of my mind and body. I had come home in fact" (44). Unsurprisingly, the image of the homecoming is that which Freud uses to characterize the girl's election of the father as second object of love.

H.D.'s devotion to Freud, however intense it may be, is not unequivocal. Ambivalence is actually the term Freud uses after Bleuler to call this oscillating and undecidable drive. In "The Writing on the Wall", the centrality of the Corfu vision can hence be construed as H.D.'s resistance not only to Freud's interpretation but also to the possibility of the cure. Turning the vision into a moment of poetic epiphany and unveiling de facto waters down what Freud considered a "danger signal". In the Tribute, H.D. strives to make a poetic and personal case for her Corfu vision, a vision she works out again and again and re-writes in what may be called in Freud's words "Durcharbeitung":

For things had happened in my life, pictures, 'real dreams', actual psychic or occult experiences that were superficially, at least, outside the realm of psychoanalysis. But I am working with the old Professor; I want his opinion on a series of events. [...] If the Professor could not do this, I thought, nobody could. I could not get rid of the experience by writing about it. I had tried that. There was no use telling the story, into the air, as it were, repeatedly like the Ancient Mariner who plucked at the garments of the wedding guest with that skinny hand. My own skinny hand would lay, as it were, the cards on the table - here and now-here with the old Professor. [...] If he could not "tell my fortune," nobody else could." (39)

What is this province outside of Freudian psychoanalysis? Is it psychosis which Freud himself regarded as ineligible for psychoanalytical treatment? In this passage, H.D. overtly confesses that the healing she was usually able to derive from the practice of writing was of no avail in the case of the writing-on-the-wall episode; being unable to deal with her anxiety, she had to turn to psychoanalysis. H.D.'s Corfu vision was not a mere poetic moment of epiphany but a psychic event in the Real whose intensity and associated anxiety she was not able bypass or short-circuit. And even if she acknowledges the strangeness of the experience, its ungrounding nature, she still resists Freud's diagnosis:

But of a series of strange experiences, the Professor picked out only one as being dangerous, or hinting of danger or a dangerous tendency or symptom. I do not yet quite see why he picked on the writing-on-the-wall as the danger-signal, and omitted what to my mind were tendencies or events that were equally important or equally "dangerous." (41)

The possibility of a cure with the Viennese psychoanalyst had however been envisaged by H.D. as a sign of election, her election by a fatherly figure (what Freud calls after Jung the father-imago, "Dynamics" 313), if not by the Father himself. In this election, she was yet fantasmatically challenged by at least two or three distinct figures: Princess Marie Bonaparte, Freud affectionately calls "our Princess", the Princess of psychoanalysis with whom she admits not to be able to even compete ("I cannot compete with her", 43), one of Freud's patients she regularly met coming down the stairs, Van de Leeuw, and Freud's grand-children he recurrently mentions. In fact, the reality of Freud's life contradicted her intimate belief and wish: H.D. has thus to navigate the existence of Freud's other patients, disciples and family. However, her sense of having been accepted by the analyst, an acceptance both intransitive and unconditional, is what justified and somehow restored H.D. as subject Acceptance in this context is intimately tied in with election, an election itself confirmed and redoubled through the reference to Moses and the Chosen people. To that extent, H.D. and Freud belonged together in H.D.'s fantasy: he belonged to the Chosen people, while she had been accepted by Him.

This originary fantasy of mutual belonging accounts for H.D.'s upset reaction when Freud implicitly called her a "stranger" during their first session. In this episode, thanks to the mediation of Freud's dog, H.D. was supposedly able to prove the professor wrong and show him how little of a stranger she was:

But worse was to come. A little lion-like creature came padding towards me - a lioness, as it happened. She had emerged from the inner sanctum or manifested from under or behind the couch (...). Embarrassed, shy, overwhelmed, I bend down to greet this creature. But the Professor says, 'Do not touch her-she snaps- she is very difficult with strangers' Strangers ? Is the Soul crossing the threshold a stranger to the Door-keeper ? It appeared so (...) If this is an exception, I am ready to take the risk. Unintimidated but distressed by the Professor somewhat forbidding manner, I not only continue my gesture toward the little chow, but crouch on the flow so that she can snap me better if she wants to. Yofi - her name is Yofi-snuggles her nose into my hand and nuzzles her head, in delicate sympathy, against my shoulder." (98)

A little further down, H.D. comes back to the episode in a both vindicative and amused posthumous address: "She snaps, does she ? You call me a stranger, do you ? Well, I will show you two things: one, I am not a stranger,; two, even if I were, two seconds ago, I am now no longer one and moreover, I never was a stranger to this little golden Yofi" (99). The entire Tribute can be read in the light of this humorous comment as a narrative and performative attempt to nonetheless prove the blameless physician wrong and re-write the tale of H.D.'s analytic experience. The unpredictable intervention of Freud's pet seems to have played an irreplaceable role in the activation of transference on H.D's part. By a non-linguisitic yet unequivocal mark of sympathy, the animal symbolically did accept her.

The circumstances of her first encounter with Freud confirmed what she felt to be an always already, if not a natural, intimate connection with the Austrian man, a man who happened to be of Moravian descent just like she was herself. Throughout the book, the metonymical connection uniting the figure of Freud and that of HD's father constantly operates, just as if one figure necessarily led to the other: "It is only now as I write this that I see how my father possessed sacred symbols, how he, like the Professor, had old, old sacred objects on his study table" (25). Freud's office at Bergstrasse synesthetically reminded H.D. of her own father's study:

There is the old-fashioned porcelain stove at the foot of the couch. My father had a stove of that sort in the outdoor office or study he had built in the garden of my first home. There was a couch there, too, and a rug folded at the foot. It too had a slightly elevated head-piece. My father's study was lined with books, as this room was. There was a smell of leather, the crackling of wood in the stove, as here. There was one picture, a photograph of Rembrandt's Dissection, and a skull on the top of my father's highest set of shelves. There was a white owl under a bell-jar. I could sit on the floor with a doll or a folder of paper dolls, but I must not speak to him when he was writing at his table. What he was "writing" was rows and rows of numbers, but I could scarcely distinguish the shape of a number from a letter, or know which was which. I must not speak to my father when he lay stretched out on the couch, because he worked at night and so must not be disturbed when he lay down on the couch and closed his eyes by day. But now it is I who am lying on the couch in the room lined with books. (19)

In this passage, the enunciative pattern oddly combines the deictic present with the preterite ("as this room was"; "There was a smell [...], as here"). The intensity of H.D.'s experience at Berggasse seems to allow for a conflation in the spatio-temporal order whereby the possibility of pure presence is not contradicted by the passing of time. This capacity she has in the Tribute and elsewhere to conjure up the past in the present is what she calls "the fourth-dimensional" time element: "The actuality of the present, its bearing on the past, their bearing on the future. Past, present, future, these three - but there is another time element, popularly called the fourth-dimensional" (23).

Yet at some point in H.D.'s narrative, the comparison between the two fatherly figures ceases while a competition of a different nature takes over. The second part of the scene just quoted which foreshadows the writing-on-the wall episode can be regarded as a "scene of writing", to take up Derrida's eponymous notion in "Freud et la scène de l'écriture", a fantasmatic and originary scene in which the father is seen seated at his desk "writing". Interestingly enough, the word "writing" is in inverted commas as if to downplay the value of the number-writing of the man of science contrasted with the letter-writing of the daughter poet. The writing-on-the-wall episode may also be reassessed in the light of this primitive writing scene.

However, this scene of writing is obliquely connected with the scene of psychoanalysis: the daughter is told to keep silent while her father is resting on the couch whereas H.D. as analysand lying on the couch is asked according to the analytic rule to speak whatever comes to her mind. The final sentence manifests H.D.'s triumph over her father achieved through therapy and the negative imperative his presence implied in relation to her barred access to speech: "But now it is I who am lying on the couch in the room lined with books". The value of this "now" cannot be overemphasized for it points to a temporality that remains undecidable as well as endlessly reiterable, the time of writing.

In the Tribute, HD deals with the Corfu vision as pure writing, a writing-on-the wall:

So far, so good - or so far, so dangerous, so abnormal a 'symptom". The writing at least is consistent. It is composed by the same person, it is drawn or written by the same hand. Whether that hand or person is myself, projecting the images as a sign a warning or a guiding sign-post from my subconscious mind or whether they are projected by the outside - they are at least clear enough, abstract and yet at the same time related to images of our ordinary time and space. (46)

By calling it a writing, by the mention of the writing or drawing hand, H.D. tries to reclaim the experience and make sense of its radical alterity. By resorting to the metaphor of writing, she is able to recover from what Freud considered to be a flight from reality; writing when it comes to the Corfu vision or to the transferential bond allows for the reshaping, remastering, appropriating of the experience.

The writing does not stop with the vision at Corfu: it immediately lends itself to further interpretations, to "visions and revisions" as Eliot would have it: "But symptom or inspiration, the writing continues to write itself or be written. It is admittedly picture-writing, though its symbols can be translated into terms of today" (51). The writing-on-the-wall becomes, as it turns out, a metaphor for the movements of the light on the wall: "But this picture or symbol begin to draw itself before my eyes. The moving finger writes. Two dots of light are placed or appear on the space above the rail of the wash-stand, and a line forms" (52). The writing amounts to the drawing of a line,

but so very slowly - as if the two rather heavy dots elongated from their own centers, as if they faded in intensity as two lines emerged, slowly moving toward one another. They will meet, it is evident, and from the pattern, (two dots on a blackboard) we will get a single line. I do not know how long it took for these two frail lines to meet and then remain one, intensified or in italics, underlined as it were (52).

The mesmerizing quality of the experience is proportional with, inseparable from the passive and strenuous state HD is reduced to. Why call this specific instance writing: "The moving finger writes" (52)? What H.D. calls writing, what she takes to be writing in this case, is handwriting in the literal sense, the writing of a hand, a hand that she cannot acknowledge as hers. The moving finger writes: the use of italics is not incidental. The typographical mark, situated beneath the level of the linguistic sign, happens to stand halfway between writing and drawing, a pure marker of intensity and affect where emotion touches on the objectivity of the mark, affects the sign, a pure stress only perceptible in writing, what Antoine Cazé calls "the pure visuality of 'the mark as such'" (77). The italics are explicitly thematized in the passage: "I do not know how long it took for these two frail lines to meet and then to remain one, intensified or in italics, underlined as it were". Only typographical marks are able to convey the intensity of the Corfu experience that language was hardly able to render. Whether the italics are to be read literally or figuratively cannot be determined. Neither Freud, nor the reader, nor H.D. herself would know. The experience, its agency and danger precisely resides in the undecidable value of the typographical mark. The object of H.D.'s perception is writing as pure phenomenon, pure intention, pure intensity, the Real dimension of writing that is never experienced by the writer, the scene of writing in real, hardly connected to the actual production of a meaningful mark. As the vision unfolded, H.D. did not concern primarily herself with the reading as much as Bryher who was standing by her side: ""Bryher who has been waiting by me carries on the 'reading' where I had left if off" (56).

The Tribute can be regarded as the poetic re-writing of an analytic cure, a re-writing as appropriating process of the writing on the wall, the appropriation of psychoanalysis through its literary re-writing. The mythological becoming of Freud both legitimatizes his theory and practice and allows H.D. to be the master of vision and its interpretation, interpreting Freud back, translating him into her own allegorical and transferential grammar:

He would stand guardian, he would turn the whole stream of consciousness back into uselful, into irrigation channels, so that none of this power be wasted. He would clean the Augean stables, he would tame the Nemean lion, he would capture the Erymanthain boar, he would clear the Stympahlian birds from the marshes of the unconscious mind. These things must be done. Until we have competed our twelve labors, he seemed to reiterate, we (mankind) have no right to rest on cloud-cushion fantasies and dreams of after-life. (103)

References

Cazé, Antoine. "'There is one line, clearly drawn' : The Visible and the Illegible in H.D." Modernism and Unreadability (Université Lumière Lyon 2,23-25 October 2008). Ed. Isabelle Alfandary & Axel Nesme. Montpellier: Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2011. 75-87. [ Links ]

Derrida, Jacques. "Freud et la scène de l'écriture" L'écriture et la différence. Paris: Seuil, 1967. [ Links ]

Doolittle, Hilda. Tribute to Freud. New York: New Directions, 1974. [ Links ]

Freud, Sigmund. "Analysis Terminable and Interminable." "Moses and Monotheism", "An Outline of Psycho-analysis" and Other Works. Trans. James Strachey. Vol. 23. London: Vintage, 2001. 216-54. Print. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works Of Sigmund Freud. [ Links ]

Freud, Sigmund. "The Dynamics of Transference." Collected Papers. Vol. 2. London: Hogarth, 1953. 312-322. [ Links ]

Friedman, Susan. Psyche Reborn: The Emergence of H.D. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1981. Print. [ Links ]

Holland, Norman N. "HD and the" Blameless Physician"." Contemporary Literature 10.4 (1969): 474-506. [ Links ]

Recebido em: 27/03/2018

Aprovado em: 05/02/2019