Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Journal of Human Growth and Development

versão impressa ISSN 0104-1282versão On-line ISSN 2175-3598

J. Hum. Growth Dev. vol.26 no.1 São Paulo 2016

https://doi.org/10.7322/jhgd.113709

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Concepts and movements in health promotion to guide educational practices

Italla Maria Pinheiro BezerraI, *; Isabel Cristina Esposito SorpresoII

IEscola de Artes, Ciências e Humanidades da USP. Laboratório de Delinemanento e Escrita Científca da FMABC

IIDocente da Atenção Primária à Saúde pela Disciplina de Ginecologia ; Departamento de Obstetrícia e Ginecologia. Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: in health promotion, practices are necessary to trigger mechanisms aimed at the creation or recreation of a new mode of enhancing health, in order to overcome the still-oriented actions of the biological approach. Prevailing actions oh health care, although important to the sector, do not advance toward a positive concept

OBJECTIVE: to analyse the historical process of health as a concept and care models in the search for a new model of health promotion

METHODS: This is a reflective review designed to understand and appraise the international and national literature from Medline/PubMed, Lilacs and the Scientific Electronic Library (Scielo). For the organisation of data, articles were separated by themes, and the process of categorisation was conducted based on content analysis

RESULTS: Despite having the knowledge that consistent actions with the assumptions of health promotion are of great importance to quality of life and equity in health, implementing them remains a challenge due to the predominance of curative practices and an individualistic approach. These practices, in turn, are revealed to be a reflection of the concept of health that has passed from the absence of disease to a process related to social, political, economic and cultural factors

CONCLUSION: The concept of health has been transformed from historical ideas, reflecting the emergence of new formulations about thinking and doing and, consequently, new proposals for changes in welfare models of health. Therefore, although the new model of healthcare has been structured from a health promotion perspective; there are still features of hegemonic models with the predominance of curative practices

Keywords: health; models of health; health promotion, education.

INTRODUCTION

Health is the greatest resource for social, economic and personal development, as well as an important dimension of quality of life. In primary care, health promotion actions aim at empowerment and autonomy for the achievement of better living conditions and health. In this context, in order to break away from predominantly curative practices, several discussions have been happening around health promotion.

The first Global Conference on Health Promotion, held in 1986 in Ottawa, is the reference mark. The ideals of health promotion were defined as the expression of coordinated action between civil society and the state, in order to implement healthy public policy, creating favourable environments, strengthening community action, developing personal skills and reorienting the health system to accomplish these goals1.

Guided by an expanded concept of health, involving conditions and determinants of health/disease process and not health as the absence of disease, the document maintains the indissolubility between the population and the environment based on a social ecological health approach, understood as a guiding principle and effective stimulating contemplation of issues related to the damage that social injustice and environmental problems impose on health as well as the creation of environments conducive to health1,2.

In the Brazilian scenario, at the forefront of the prevalence of hegemonic models such as privatisation and sanitarian, action was taken to change the models of health. So, with the Brazilian health reform movement during the 1980s, the formulation of the national health system, the Sistema Unico de Saúde (SUS), in the Constitution of 1988 and its deployment in the last two decades, the health system in Brazil has reached the 21st century organised around a model of health promotion3,4.

From this perspective, the Ministry of Health has deployed the Family Health Strategy (FHS) in order to reorient health practices. To take responsibility for the health of the population, territorial teams must broaden the curative-preventive practice of the traditional biomedical model, seeking to promote quality of life. This is one of the main foundations of the present healthcare model5,6.

Health promotion is considered to be one of the strategies of health production, i.e. as a way of thinking and operating in coordination with other policies and technologies developed in the Brazilian health system, contributing to the development of actions to respond to social needs in health7. The FHS was based on this logic. The health promotion proposal was assessed and was incorporated into the actions to be developed in the strategy to understand its dimensions regarding the quality of life of the population. Although the reorientation of the care model in which the FHS is a formal proposal, the field of concrete practices remains under construction and, as a result, elements of both models co-exist for health care8.

In health promotion practices, it is necessary to trigger mechanisms aimed at the creation of a new modus operandi, in order to overcome the still-oriented actions of the biological approach. These prevailing preventative-oriented actions, although important to the sector, do not advance a positive concept of health, as health education. This situation occurs at both the training and professional performance levels, which contributes to the permanence of a vicious cycle in which theory and practice reiterate traditional models of action9.

Thus, this study provides a theoretical reflection on the concepts of health and the different social models. The objective is to analyse the historical process of the concept of health and care models in health promotion models.

METHODS

This is a reflective review study, employing sources from the international and national literature from the databases Medline/PubMed, Lilacs and the Scientific Electronic Library (Scielo).

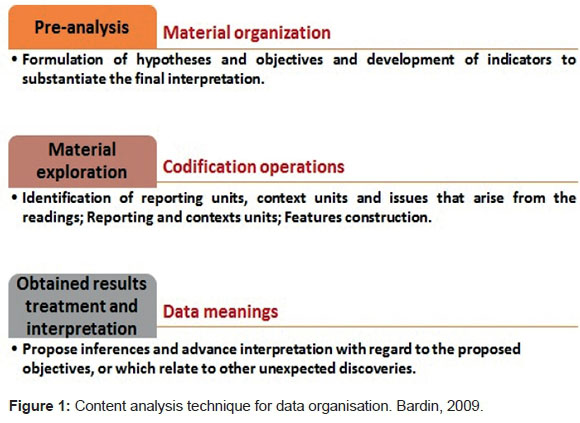

For organisation of the data, articles were separated into themes and a process of categorisation was conducted based on content analysis according to Bardin10, by following the steps below:

RESULTS

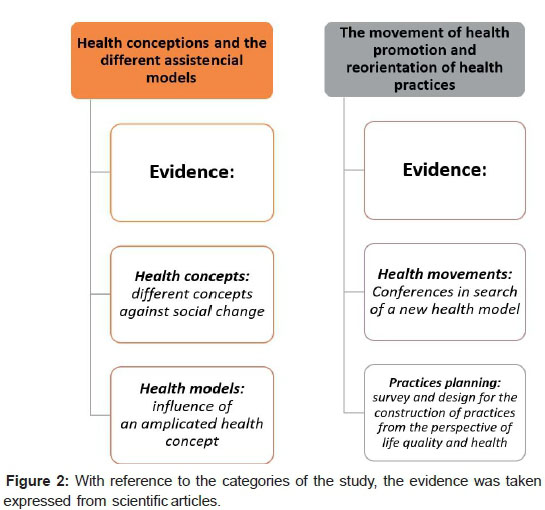

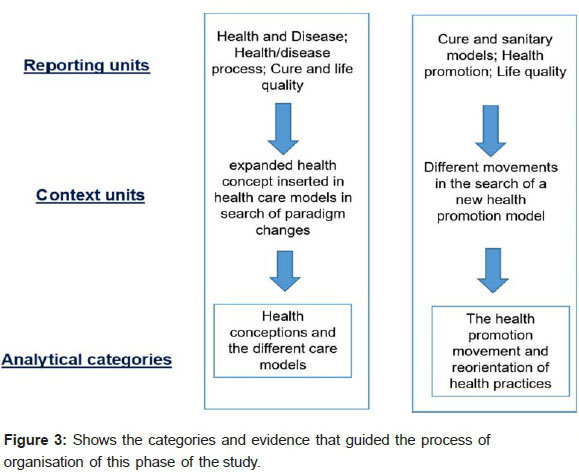

By following the technique of data organisation by content analysis, two empirical categories were built from the registration units and context, as proposed below:

DISCUSSION

Two categories of analysis were used in the categorisation process: concepts of health and the different care models and assistance, and the health promotion movement and the reorientation of practices.

It was shown that although the knowledge that action consistent with the assumptions of health promotion exist, and are of great importance to quality of life and equity in health, implementing them is still a challenge, given the predominance of practices with curative and individualistic characteristics. These practices, in turn, are revealed as a reflection of the concept of health that is structured from the absence of disease to a process related to socioeconomic, political, economic and cultural factors, leading, in this way, to actions focused on health promotion or focused on curing the disease.

Conceptions of health and the different social models

The incremental social transformations of capitalism have meant that the human body can be seen as a source of profit, both for those receiving care and those who provide care, because this constitutes a workforce. This reality, where the control of this workforce appears necessary, uses health as one of the mechanisms capable of enabling this task. As a result of these changes, the appearance of new ways of thinking and emerging proposals for changes in welfare models of health should be noted11-12.

These changes in social assistance models are conditioned to what is meant by the concept of health, since it is a concept that brings particular features with a historical context. For Czeresnia, Maciel and Oviedo13, there is not a widespread definition of health, as it is a concept that may depend on values, expectations and attitudes in daily life. In this way, the concept of health is discussed depending on the historical context and/or the world view of the health concept which has accompanied social, political and economic changes that directly and indirectly influence the formulation of this concept.

Seeking an understanding of health has been a topic of reflection of many medical theorists, among them Galen, a Greek physician, who brought forward the concept of health as a balance between the primary parts of the body. Even in antiquity, it was believed that disease could be caused by natural or supernatural elements; an understanding of disease was through religious philosophy. The causes were related to the physical environment, the stars, the weather, insects and animals14.

In the Middle Ages, with a religious vision of disease and with epidemics of increasing frequency, the idea of contagion among people was incorporated, although the causes were attributed to the conjugation of the stars, or the poisoning of water by lepers, Jews or witchcraft. In the Renaissance, empirical studies led to the formation of the basic sciences, accompanied by the need to discover the origin of substances that cause infections. At this point, the miasmatic theory arose15.

From end of the 18th century to the early 20th century, a space was opened up for individual medical practice which gradually came to occupy the central place in health practices, revealing or appearing the social medicine. The 19th century brought about the advent of bacteriology and the idea that for every disease an etiological agent exists that could be fought with chemicals or vaccines. Medicine is influenced by this empiricism even today16. However, in the 19th century, cellular pathology, bacteriology, physiology and the development of research arose, with the medicine of empirical science giving way to experimental science13. Modern medicine directs its activities toward the body and disease in search of a normal biological state17.

In this way, the conception of health that guides biomedicine originated in modern science and was characterised by explaining the phenomena of life with a reductionist vision under the influence of Cartesian epistemology. Health was understood from the workings of the human body and the anatomical and biological changes occurring in disease18. With the Flexner Report, published in 1910 in United States, this vision has assumed a significant role and is reflected in the organisation of health services in the Western world. The bases of the report were that the study of medicine is focused on disease, not social and collective concepts, thus driving criticism of this model19.

Following discussions on the concept of health, on 7 April 1948, the World Health Organisation (WHO) disclosed as a health concept the state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease20. This concept has generated multiple reviews by amplitude, subjective character and idealisation of perfect well-being, approaching a utopia.

In 1978, as a result of these criticisms, the International Conference on Primary Health Care Assistance (Alma-Ata), promoted by WHO, approved an extended concept emphasising the health inequalities between developed and underdeveloped countries, the responsibility of government in the provision of health care and the importance of the participation of individuals and communities in the planning and implementation of health care21.

Since then, the concept of health has been transformed over the years, characterised as a process that involves social, political and economic aspects, under the influence of significant changes depending on the context. As this concept includes the lives of men and women, health, in its diversity and uniqueness, was affected by the societal changes of the last few centuries. The process of societal transformation is also the process of transforming health and sanitation7.

According to Bezerra et al.22, the health/disease process was significantly impacted by political, social, economic and cultural changes in recent centuries. This has influenced the provision of health services, as well as the quality of life of the population. In Brazil, mediated by political and economic interests, the history of health underwent many changes until the creation of the current health system. According to each period, new needs and interests appeared. These changes come on gradually, leading to the consolidation of one of the largest public health systems in the world, the national health system (SUS)23. In this way, every attempt to reorganise the health care system in Brazil brings with it the construction of new paradigms within the context of health policies and health services24, reflecting the period, the economic state and the dominant classes.

Considering the historical context, health policies in Brazil have led to a structured health system, initially through sanitation campaigns and with the implementation of social welfare, which established the separation of public health, social medicine and liberal medicine (1920-1950). In the second half of the 20th century, with privatisation, a health crisis and the search for alternatives, the private assistance medical model was established (1960-1970). Gradually, the health system was structured and supported by these strategies, and after the implementation of the Constitution in 1988, the social construction of the national health system (SUS) continued with the purpose of organising health services according to the principles and guidelines established by the Constitution of the Republic25.

The essence of the "sanitarist" care model is in the confrontation of selected health problems and in meeting the specific needs of certain groups through campaigns and special programmes (tuberculosis, leprosy, pregnant women, among others). This refers, therefore, to collective, sanitarian and massive initiatives, typical of institutionalised public health in Brazil during the 20th century25.

Conversely, in the medical care privatist model, identified as a hegemonic hospital-centric medical model, the design of biomedical practice is based on individual patient care and operates with a biological understanding of the health-disease phenomenon, centred on the healthcare professional25. In the mid-1970s, the struggle for the democratisation of policies acquired new characteristics and strategies. Previously confined to universities, clandestine parties and social movements, this began to be located within the state itself. All this democratic effervescence intensified in the 1980s with the emergence of a social group from the new unionism and urban movements, building an opposition party. Moreover, this led to the organisation of sectoral movements able to formulate institutional reorganisation projects, such as the Health Movement26.

According to Silva27, in the 1980s, the changing political spectrum through the mobilisation of civil society, as well as the organisation of movements for the achievement of health as a universal right of citizens and a duty of the state was consolidated, aiming to conceive social, political and economic dimensions of medical practice and health assistance. With these actions, health is taken away from the strictly technical sphere and breaks up the prevention-cure dichotomy in the construction of this new object of study and action, including prevention in the context of health.

The options for strengthening public policies and building on the foundations of the social welfare state were seen as priorities, unifying the demands of most progressive sectors. The construction of a health reform project was part of the struggle of resistance to dictatorship and its model of the privatisation of social health services and by the construction of a democratic social state26.

In the context of Brazilian health, specifically regarding how their policies are defined, there was a paradigm-shifting proposal related to assistance models with the advent of health reform. New concepts were proposed that were enacted in the Federal Constitution of 1988, through the SUS, with its principles of integrity, universality and equity9. The concept of health stands out according to the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, and is considered a result of improved conditions in terms of food, housing, education, income, environment, work, leisure, land tenure and access to health services28.

The legal basis of SUS are explained in the text of the Constitution of 1988, in the state constitutions and in the organic law of municipalities, which incorporated and detailed in Brazil. However, regulation was established at the end of 1990, with Laws 8080 and 8142, in which the organisational and operational principles of the system are laid out, such as the construction of a model of attention instrumentalised by epidemiology, a regionalised system with local bases and social control, and, by successive laws, which since then have expanded the national legal framework on health29.

It should be noted that, as well as the principles of organisation of the system (decentralisation, regionalisation, ranking, resolution and complementarity in the private sector), the doctrinal principles of universality of access to health services at all levels of assistance, of completeness of care, are understood as a set of actions for continuous preventive and curative services. These are individual and collective, required for each case at all levels of complexity of the system to promote equity in health care, without prejudice or privilege of any kind, and with the participation of the community30.

The SUS was conceived for the purposes of restructuring the assistance model so that it would be different to the overwhelming dichotomy between curative and preventive practice. The change should have included an organisational restructuring of teams and health services, with the objective of greater contact with patients, capable of resolving problems as they occur31.

According to Ermel and Fracolli32, following the deployment of SUS in the late 1980s, public health services have undergone a process of revising the care model, so new practices have been instituted and others abandoned. With criticism of the hegemonic care model, alternative proposals emerged, highlighting the family health strategy (FHS) program deployed in 1994, a broadened conception of health inspired by adopting what was defined in the eighth National Health Conference (NHC/CNS) in 1986, the universal right to health, as defined in the Federal Constitution of 198827 and in the guidelines of the primary care health policy, formulated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in Alma-Ata in 1978. The FHS aims to implement a new model of care based on completeness, with a focus on family and community health surveillance and with the view of health as expanded33.

It can be said that the FHS is an alternative to overcome the dominant paradigm in the health care field, since it proposes a change in the design of the health-disease process, distancing itself from the traditional model centred on offering services geared to the disease. It also invests in actions involving health, living conditions and quality of life, i.e. health promotion actions34.

The health promotion movement and the reorientation of health practices

Health promotion developed as new concept in international health in the mid-1970s, as a result of the discussion in the previous decade on the determination of social and economic health and the construction of a non-disease-centred design35.

It is important to mention two events: the opening of nationalist China to the outside world with the completion of the first two Western expert observation missions promoted by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 1973-1974, and the Canadian movement developed from the Lalonde Report: A New Perspective On Canadians' Health (1974), later reinforced with the Epp Report: Achieving Health For All36.

Those two events set the foundation for key convergence movements to shape a new paradigm formalised in the Alma-Ata Conference in 1978, with the proposal of health for all in the year 2000 and a primary health care strategy, particularly during the first international conference on health promotion in 1986, with the enactment of the Ottawa Charter, which has been enriched with a series of statements issued periodically at international conferences held on the theme36.

The Alma-Ata Conference, which focused on primary health care and aimed to reaffirm the promotion and protection of the health of people, was essential to continued economic and social development and contributed to improved quality of life and world peace, since it is a right and a duty of the people to participate individually and collectively in the planning and implementation of their health care36.

The first Global Conference on Health Promotion was held in Ottawa (Canada) in 1986, known as the Ottawa Charter for health promotion, and presented itself as a response to growing expectations and restructuring public health. In this context, the Ottawa Charter for health promotion sets out health promotion as a process of empowerment of the community to act toward the improvement of their quality of life and health, including greater participation in the control of this process. In addition to reaching a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, individuals and groups should be able to identify aspirations, satisfy needs and modify their environment36.

According to the Ottawa Charter, to achieve health, some prerequisite conditions are required, such as peace, housing, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice and equity. The conditions required to build a solid foundation for enhancing health conditions are defence, training and mediation. This also addresses the five axes of health promotion actions: building healthy public policy, creating favourable environments, strengthening community action, developing personal skills and reorienting health services36.

Since then, several Global Conference on Health Promotion meetings have been held. The second one was held in1988 in the city of Adelaide (Australia) and produced a document known as the Declaration of Adelaide. It reaffirmed the five actions of the Ottawa Charter for health promotion, and prioritised the first action, i.e. healthy public policies, because this is a priority for the implementation of the other actions. Therefore, a healthy public policy concerns all areas of public policy in relation to health and equity, and assesses the impact of such policies on the health of the population, with its main purpose the creation of a favourable environment so that people can live healthy lives36.

The third Global Conference on Health Promotion was held in Sundsvall (Sweden), in 1991 and had as its objective the formation of favourable environments and health promoters. Then, in 1997, a discussion on health promotion in the 21st century was held in Jakarta as the fourth Global Conference on Health Promotion. This was a reiteration of the actions and conceptions of previous conferences, stating that health is a fundamental human right and is essential for social and economic development. The promotion of health is a key element in the development of health36.

In Mexico City, in 2000, the fifth Global Conference on Health Promotion focused on making health promotion a key priority of local policies and programmes at the regional, national and international levels, to take a leadership role to ensure the active participation of all sectors and of civil society in the implementation of health promotion actions that strengthen and expand partnerships in the area of health, to produce national action plans for the promotion of health and to establish or strengthen the national and international networks which promote health36.

The sixth Global Conference on Health Promotion was held in Bangkok (Thailand) in August 2005. This meeting investigated changes in the context of global health, including the increased incidence of chronic and communicable diseases, including heart disease, cancer and diabetes. The goal was to give new direction to health promotion to achieve health for all through four commitments: the development of a global agenda, the responsibility of all governments, the main goals of the community and of civil society, and the need for good administration practice37.

The seventh Global Conference on Health Promotion was held in Nairobi (Kenya) in 2009. This provided the opportunity to share experiences in primary health care38.

Finally, the eighth Global Conference on Health Promotion was held in Helsinki (Finland) in 2013. The meeting was based on a rich heritage of ideas, actions and evidence originally inspired by the Declaration of Alma-Ata on primary health care (1978) and the Ottawa Charter for health promotion (1986). A commitment to the highest standard of health for all was recognised, and that governments have the responsibility for the health of all their people. Health was discussed in the context of all policies as an integral part of the contribution of countries to achieve the Millennium Development Goals of the United Nations39.

In the Brazilian scenario, over the years, assistance health models have been different, initiated by private medical care after the sanitation model. This was done in order to solve problems based on individual assistance or curative assistance, geared primarily toward an individual's illness, which consequently has not been effective at solving the health problems of the population40.

Paim25 revealed that, in Brazil, political movements against the dictatorship were expressed as what is known as health reform, resulting in SUS. Its formalisation was set at the 8th National Health Conference, held in 1986, whose final report identifies unequal access to health services, inadequate services, poor quality of services and lack of completeness of actions.

In this scenario, the family health program was implemented in 1994, known as the Family Health Strategy (FHS). This model of care comes from the direction of reorganisation of the assistance model linked to the principles and guidelines of the SUS, especially for being a space for the construction of citizenship. The health professionals involved must develop educational activities from a family/community perspective41. However, in order to deploy those educational activities with an emphasis on health promotion, the Health Ministry has initiated discussions on health promotion, and after many experiments and discussions worldwide and Brazil, the first basic document proposing the creation of a National Health Promotion Policy was prepared35.

Since 2004, health promotion became part of the Secretariat of Health Surveillance to contribute to the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases and their risk factors, which are responsible for high mortality in Brazil. In this context, the actions of health promotion were more accepted among health professionals, had more content and focus on behaviour as the source of controllable risks such as diet, tobacco use, alcohol and drugs and a sedentary lifestyle, without considering the conditions that interfere in the personal options42.

Several discussions took place for the definition of the National Policy of Health Promotion, and policy design was provided. The distance between the conceptions of the Ministry of Health and the international charters on health promotion that were previously set by the participants of the Working Group on Health Promotion of the Brazilian Collective Health Association was minimised11.

On March 30, 2006, the National Policy for the promotion of health was published through the gatehouse 687 MS/GM, with the objective of improving the quality of life of the population and reducing vulnerability and health risks related to their determinants and conditions: way of life, working conditions, housing, environment, education, leisure, culture, access to goods and essential services7.

It is recognised that the health-disease process is associated determinants and broader restrictions, impossible to modify only by the biomedical apparatus. This favours the expansion of healthy choices by the subjects and their community in the territory where they live and work5. From this perspective, with the implementation of the FHS, the focus of attention changed, i.e. it was no longer centred exclusively on the individual and on disease, but more on the collective and the family as the privileged space of action, with practice based on ethical and moral principles, leading to greater autonomy of users, with a view to promoting health43.

Thus, after the implementation of the FHS, the performance of health professionals turned not only to an individual's illness, but also to the promotion of the health of the whole family and community41. In this way, the promotion of health is considered a strategy for the production of health, namely as a way of thinking and acting articulated to other policies and technologies developed in Brazil's health system, collaborating with the development of actions that make it possible to respond to social needs in health7.

The assistance implemented by the FHS distances itself from the traditional model since it proposes changes in the design of the health-disease process and also invests in actions involving health with living conditions and quality of life, as the actions of health promotion33.

The family health team, composed of a multidisciplinary team with a doctor, nurse, dentist, dental office assistant or technician in dental hygiene, nursing assistant or nursing technician and community health agent, among others, is responsible for customer registration and monitoring of the population, in order to act in the execution of these actions of health basic care7. These teams expand their approaches to health and become collaborators responsible for the construction of citizenship by adopting the practice of health education advocated by the Ministry of health. This view creates a democratic approach between citizens and the public body, strengthening health education concepts as well as popular participation and social control. These health professionals should develop their skills and abilities in an integrated manner to operationalise health actions, leading to improved quality of life44.

It is worth noting that despite several discussions on health promotion and the reorientation of health practices, discussions continue regarding the change of practice in not a promoter of health perspective, which may be related to training of professionals.

According to Chiesa et al.3, the development of the health care professional form this perspective of health promotion requires early academic insertion into the world of work, in addition to the construction of a critical and reflective view of health, with health promotion as the central axis. In this way, development-oriented curricula of the competencies required to work in health care at SUS should provide educational opportunities that ensure students apply theoretical knowledge and develop not only technical skills, but also political skills and relationships. This initial training of professionals in the field of health promotion is necessary due to the still predominantly biological focus, privatist medical care and disjointed health practices3. However, even with the knowledge that actions consistent with the assumptions of health promotion are still in the process of construction, practices with characteristics of hegemonic models still exist in health care.

The results show that the concept of health has transformed from historic moments times, reflecting on the emergence of new formulations about thinking and doing and, consequently, new proposals for changes in welfare models of health. So, although the new model of attention to health is structured from a health promotion perspective, there are still features of hegemonic models involved in curative practices.

REFERENCES

1. Buss PM, Pellgrini Filho A. A saúde e seus determinantes sociais Physis. 2007;17(1):77-93. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312007000100006 [ Links ]

2. Porto MFS, Pivetta F. Por uma promoção da saúde emancipatória em territórios urbanos vulneráveis. In: Czeresnia D, Freitas CM. Promoção da saúde: conceitos, reflexões, tendências. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2009; p.207-229. [ Links ]

3. Chiesa AM, Nascimento DDG, Braccialli LAD, Oliveira MAC. A formação de profissionais da saúde: aprendizagem significativa à luz da promoção da saúde. Cogitare Enferm. 2007;12(2):236-40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/ce.v12i2.9829 [ Links ]

4. Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, Bahia L, Macinko J. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet. 2011 May 21;377(9779):1778-97. DOI: ttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60054-8 [ Links ]

5. Macinko J, Harris MJ. Brazil's family health strategy-delivering community-based primary care in a universal health system. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(23):2177-81. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1501140 [ Links ]

6. Freitas MLA, Mandú ENT. Promoção da saúde na Estratégia Saúde da Família: análise de políticas de saúde brasileiras. Acta Paul Enferm. 2010; 23(2):200-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21002010000200008 [ Links ]

7. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Política nacional de promoção da saúde. Secretaria da Atenção Básica. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2006. [ Links ]

8. Silva CP, Dias MSA, Rodrigues AB. Práxis educativa em saúde dos enfermeiros da Estratégia Saúde da Família. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2009; 14(1):1453-62. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232009000800018 [ Links ]

9. Silva KL, Sena RR, Grillo MJC, Horta NC. Formação do enfermeiro: desafios para a promoção da saúde. Esc Anna Nery Rev Enferm. 2010;14(1):368-76. [ Links ]

10. Bardin L. Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70; 2002. [ Links ]

11. Carvalho SR. As contradições da promoção à saúde em relação à produção de sujeitos e a mudança social. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2004;9(3):669-78. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232004000300018 [ Links ]

12. Lucena ADF, Paskulin LMG, Souza MFD, Gutiérrez MGRD. Construção do conhecimento e do fazer enfermagem e os modelos assistenciais. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2006;40(2):292-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342006000200020 [ Links ]

13. Silva AC, Ferreira J. Czeresnia D, Maciel EMGS, Oviedo RAM. Os sentidos da saúde e da doença. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2015;20(3):957-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015203.00212014 [ Links ]

14. Helman CG. Cultura, saúde e doença. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2003; p.431. [ Links ]

15. Barata RCB. A historicidade do conceito de causa. In: Associação Brasileira de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Coletiva; Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública. Textos de apoio: epidemiologia. Escola Nacional de Saúde Coletiva. 1985; p.13-27. [ Links ]

16. Gonçalves RBM. Práticas de saúde e tecnologia: contribuição para a reflexão teórica. OPAS; 1988; p.68. [ Links ]

17. Backes MTS, Backes DS, Meirelles BHS, Erdmann AL. Notions of nature and derivations for health: an incursion in literature. Physis. 2010;20(3):729-51. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312010000300003 [ Links ]

18. Capra F. O ponto de mutação: a ciência, a sociedade e a cultura emergente. São Paulo: Cultrix; 1982. [ Links ]

19. Kemp A, Edler FC. Medical reform in Brazil and the US: a comparison of two rhetorics. Hist Ciênc Saúde-Manguinhos. 2004;11(3):569-85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702004000300003 [ Links ]

20. World Health Organization (WHO). Officials Records of the World Health Organization. New York: WHO; 1948. [ Links ]

21. Fertonani HP, Pires D. Concepção de saúde de usuários da Estratégia Saúde da Família e novo modelo assistencial. Enfermagem Foco. 2010;1(2):51-4. [ Links ]

22. Bezerra IMP, Alves SAA, Machado MFAS, Zioni F, Antão JYFL, Martins AAA, et al. Health Education For Seniors: An Anal In Light Of Paulo Freire's Perspective. Int Archiv Med. 2015;8(28):1-9 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3823/1627 [ Links ]

23. Pontes APM, Cesso RGD, Oliveira DC, Gomes AMT. Ease of access revealed by users of the Single Health System. Rev Bras Enferm. 2010;63(4):574-80. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672010000400012 [ Links ]

24. Cardoso JP, Vilela ABA, Souza NR, Vasconcelos CCO, Caricchio GMN. Formação interdisciplinar: efetivando propostas de promoção da saúde no SUS. Rev Bras Promoção Saúde. 2007;20(4):252-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5020/18061230.2007.p252 [ Links ]

25. Paim JS. Modelos de Atenção e Vigilância da Saúde. In: Rouquayrol MZ, Almeida Filho N. Epidemiologia e Saúde. 6 ed. São Paulo: Medsi; 2003. [ Links ]

26. Teixeira CF, Solla JP. Modelo de atenção à saúde: promoção, vigilância e saúde da família. Salvador: Ed UFBA; 2006; p.236. [ Links ]

27. Fleury S. Reforma sanitária brasileira: dilemas entre o instituinte e o instituído. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2009;14(3):743-52. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232009000300010 [ Links ]

28. Brasil. Constituição (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília: Senado Federal; 1988. [ Links ]

29. Vasconcelos CM, Pasche DF. O Sistema Único de Saúde. In: Campos GWS, Minayo MCS, Akerman M, Drumond Júnior M, Carvalho YM. Tratado de Saúde Coletiva. 2 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Hucitec; 2008; p45-67. [ Links ]

30. Brasil. Presidência da República. Lei 8.080, de setembro de 1990. Dispõe sobre as condições para a promoção, proteção e recuperação da saúde, a organização e o funcionamento dos serviços correspondentes e dá outras providências. Brasília: 1990. [ Links ]

31. Campos CEA. O desafio da integralidade segundo as perspectivas da vigilância da saúde e da saúde da família. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2003;8(2): 569-84. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232003000200018 [ Links ]

32. Andrade FR, Narvai PC. Inquéritos populacionais como instrumentos de gestão e os modelos de atenção à saúde. Rev Saúde Pública. 2013;47(suppl. 3):154-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-8910.2013047004447 [ Links ]

33. Tesser CD, Garcia AV, Argenta CE, Vendruscolo C. Concepções de promoção da saúde que permeiam o ideário de equipes da estratégia saúde da família da grande Florianópolis. Rev Saúde Públ Santa Cat. 2010;3(1):42-56. [ Links ]

34. Puttini RF, Pereira Junior A, Oliveira LR. Modelos explicativos em Saúde Coletiva: abordagem biopsicossocial e auto-organização. Physis. 2010;20(3): 753-67. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312010000300004 [ Links ]

35. Brasil. Ministério da saúde. As cartas da promoção da saúde. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2002. [ Links ]

36. World Health Organization (WHO). Bangkok charter for health promotion in the a globalized world. Geneve: WHO; 2005. [Cited 2014 sep 02] Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/6gchp/bangkok_charter/en/ [ Links ]

37. World Health Organization (WHO). The Nairobi Call to Action for Closing Implemantation . 7ht Global Conference on Health Promotion. Nairobi Kenia: Who; 2009. [ Links ]

38. World Health Organization (WHO). 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion: the Helsinki Statement on Health in All Policies. Geneva: 2013. [Cited 2014 02 sep 02] Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/8gchp/en/index.html [ Links ]

39. Silva JL. A prática educativa como expressão da prática profissional no contexto saúde da família do Rio de Janeiro. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade do Estado de Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: 2010. [ Links ]

40. Akerman M. Delineando um marco conceitual para a Promoção da Saúde e da Qualidade de Vida. Abrasco-Pró-GT de Promoção da Saúde e DLIS. Rio de Janeiro-Porto Alegre; 2003. [ Links ]

41. Vanderlei MIG, Almeida MCPD. A concepção e prática dos gestores e gerentes da estratégia de saúde da família. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2007;12(2):443-53. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232007000200021 [ Links ]

42. Roecker S, Marcon SS. Educação em saúde: relatos das vivências de enfermeiros com a Estratégia da Saúde Familiar. Investig Educ Enferm. 2011;29(3):381-9. [ Links ]

43. Fernandes MCP, Backes VMS. Educação em saúde: perspectivas de uma equipe da Estratégia Saúde da Família sob a óptica de Paulo Freire. Rev Bras Enferm. 2010;63(4):567-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672010000400011 [ Links ]

44. Coelho RFN, Leite ES, Oliveira FB, Farias MCAD, Abreu RMSX, Torquato JA. Impact of the actions of an interdisciplinary team in the elderly quality of life. Int Arch Med. 2015;8(175):1-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3823/1774 [ Links ]

Manuscript submitted: Nov 22 2015

Accepted for publication Dec 19 2015.

* Corresponding author: Itala Maria Pinheiro Bezerra - Email: itallamaria@usp.br