Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Estudos de Psicologia (Natal)

versão impressa ISSN 1413-294Xversão On-line ISSN 1678-4669

Estud. psicol. (Natal) vol.25 no.2 Natal abr./jun. 2020

https://doi.org/10.22491/1678-4669.20200013

DOI: 10.22491/1678-4669.20200013

DOSSIER COVID

COVID-19 and attitudes toward social isolation: The role of political orientation, morality, and fake news

COVID-19 e atitudes frente ao isolamento social: o papel das posições políticas, moralidade e Fakes News

COVID-19 y actitudes frente al aislamiento social: El papel de los posicionamientos políticos, moralidad y noticias falsas

João Gabriel ModestoI,II; Daniel Oliveira ZacariasII; Luccas Moraes GalliII; Beatriz do Amaral NeivaII

IUniversidade Estadual de Goiás

IICentro Universitário de Brasília

ABSTRACT

Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic is a global challenge, and social isolation is one of the main strategies for preventing contagion. In Brazil, however, discussions concerning isolation have been inserted in the political arena of an already polarized context. In this context, this study sought to investigate the role played by morality and Fake News in the relationship between political orientation and attitude towards social isolation. A total of 147 people participated in the survey, indicating their political orientation and responding to social isolation measures, Fake News and morality. The results indicate that political orientation directly influences social isolation, regardless of belief in Fake News and morality indices. It is concluded that the country's political polarization seems to be becoming a public health problem during the pandemic.

Keywords: social isolation; morality; political psychology.

RESUMO

O enfrentamento da pandemia da COVID-19 é um desafio global, sendo o isolamento social uma das principais formas de prevenção do contágio. No Brasil, no entanto, a discussão sobre o isolamento tem se inserido na arena política de um contexto já polarizado. Nesse âmbito, a presente pesquisa buscou investigar o papel exercido pela moralidade e pelas Fake News na relação entre posições políticas e atitude frente ao isolamento social. Participaram da pesquisa 147 pessoas, que indicaram suas posições políticas e responderam a medidas de isolamento social, Fake News e moralidade. Os resultados indicaram que a posição política exerceu uma influência direta no isolamento social, independente da crença em Fake News e dos índices de moralidade. Conclui-se que a polarização política do país parece estar se transformando em um problema de saúde pública durante a pandemia.

Palavras-chave: isolamento social; moralidade; psicologia política.

RESUMEN

El enfrentamiento de la pandemia de COVID-19 es un desafío global para cual el aislamiento social es una de las principales formas de prevención. Sin embargo, en Brasil, la discusión sobre el aislamiento ha ocurrido en un ambiente político polarizado. La presente investigación tuvo como objetivo estudiar el papel ejercido por la moralidad y por las noticias falsas en la relación entre posicionamientos políticos y actitudes frente al aislamiento social. Participaron del estudio 147 personas, que indicaron sus posicionamientos políticos y respondieron a medidas de frecuencia de aislamiento social, creencia en noticias falsas y moralidad. Los resultados indicaron que el posicionamiento político ejerció una influencia directa sobre el aislamiento social, independiente de la creencia en noticias falsas y de los índices de moralidad. Se concluye que la polarización política del país parece estar transformándose en un problema de salud pública durante la pandemia.

Palabras-clave: aislamiento social; moralidad; psicología política.

The high dissemination and spread of COVID-19 virus has generated a global pandemic status, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2020b). Since then, actions to battle COVID-19 have been proposed, and the main strategy recommended for the general population comprises social isolation (Hellewell et al., 2020). Although adopted strategies should focus exclusively on technical criteria, discussions concerning social isolation have been inserted in the Brazilian political arena. Given the importance and complexity of this phenomenon, the psychosocial aspects of people's attitude towards social isolation in Brazil are relevant. In this context, this study aimed to investigate the role played by morality and belief in Fake News in the relationship between political orientation and attitudes towards social isolation in Brazil.

Social isolation, one of the main actions to prevent the spread of COVID-19, aims at reducing the circulation of high numbers of people, with the goal of reducing the spread of the virus and, consequently, avoiding the overload of health systems (Hellewell et al., 2020). Despite their importance, social isolation-based strategies tend to produce negative psychological and economic effects (Brooks et al., 2020), which makes their implementation difficult. In this sense, awareness-raising actions among the population, always guided by technical criteria, are required. However, what should be the center of technical analyses has entered the political arena in Brazil, since the current president has minimized COVID-19 consequences, opposed isolation, and even participated in political demonstrations (Borges, 2020). The president's stance was even the subject of an editorial by The Lancet (The Lancet, 2020), in which risks to the country were discussed. With these episodes, social isolation seems to configure another agenda for a politically polarized Brazil.

Brazil has experienced political polarization since the country's re-democratization period, considering that the trends observed during the presidential elections during that period comprised one leftist candidate and one more to the right between the two most voted candidates. However, this polarization intensified during the June demonstrations of 2013 which, although they began as protests against increased bus fares, were led by right-wing groups, and became demonstrations against the government of the former president Dilma Rousseff. Increased polarization continued with Dilma Rousseff's impeachment in 2016, with the arrest (and subsequent release) of former President Luiz Inácio "Lula" da Silva and with the election of Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 (Santos & Tanscheit, 2019). This polarization process has affected the Brazilian population at different levels and as mentioned previously, seems to have become visible also during the pandemic period.

In one study conducted on the social representations of Brazilians concerning COVID-19, findings indicate that, concerning a broad picture of the public health crisis faced at the moment, one of the axes of the representations referred to the role of the heads of state (more specifically, the president) and their positions at the time of the crisis (Do Bú, Alexandre, Bezerra, Sá-Serafim, & Coutinho, 2020). The authors suggest that this may refer to an opposition or support of the president's speech regarding the social isolation period and suggest that new studies analyze both the social and political variables that interfere in the population's position in the face of the pandemic.

In the same way, regarding the importance of psychosocial pandemic aspects, in early February 2020, the World Health Organization indicated that coping with COVID-19 has been made more difficult due to a "infodemia" (WHO, 2020a), given the rapid and strong spread of digital media disinformation, making access to reliable information more difficult and resulting in population health and well-being consequences.

Therefore, it is relevant to analyze the context of Brazilian polarization and beliefs in Fake News concerning COVID-19 that have affected the pandemic fight. Besides, we believe that another dimension can also be explored, alongside political orientation, of morality, given that differences in the morality field aid in understanding the Brazilian political context polarization (Gloria-Filho & Modesto, 2019).

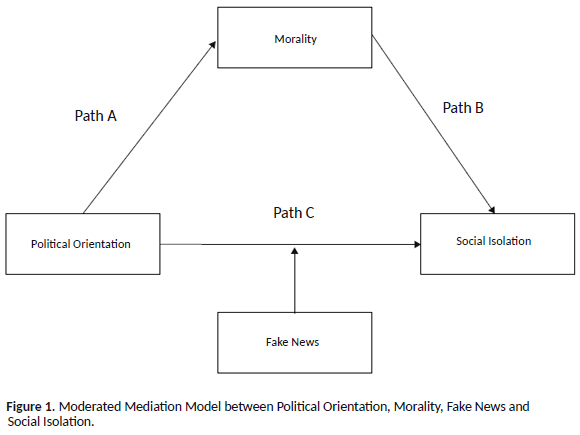

To articulate these variables, we propose a moderated mediation model, presented in Figure 1.

It is believed that (H1), in a polarization context, political orientation will interfere in attitudes towards social isolation, with participants identifying more with the right displaying a more negative attitude, while leftist participants will exhibit a more favorable position towards isolation. Additionally, (H2), this relationship will be mediated by morality, considering that the Brazilian right-wing and the left-wing are guided by different moral foundations (Gloria-Filho & Modesto, 2019). It's also hypothesize (H3) that Fake News will moderate the effect of political positioning on social attitudes; in other words, the more to the right and the higher the belief in Fake News, the more negative the attitude towards social isolation.

Moral Foundations Theory

The Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) proposes that morality be understood as a multidimensional phenomenon. Five main sets of concerns that make up the psychological basis of human morality are identified, each directly associated with adaptive challenges (Haidt & Joseph, 2007), from comparative studies concerning primate sociability, as well as anthropological studies related to morality variations in different societies (Graham et al., 2011). The foundations are theorized from opposites (Graham et al., 2011), presenting the valued principle and its negation, as follows: care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion and sanctity/degradation.

Care/harm foundation refers to the need to protect offspring, which is essential for evolutionary mammal success. In the case of humans, this foundation extends beyond offspring, encompassing everything that may represent vulnerability or infantility. These triggers tend to generate feelings of compassion as an output, so that the individual feels motivated to alleviate the suffering of others. The foundation of fairness/cheating is a tendency for the individual to display emotional reactions to cooperation or cheating situations. When exposed to situations that refer to cheating, i.e., a situation in which only one side benefits, individuals tend to exhibit anger as an output, while cooperation involves feelings of gratitude (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Joseph, 2007). These two foundations make up the individualizing foundation, as they emphasize the avoidance of suffering and value the guarantee of the rights and well-being of individuals (Graham et al., 2011).

The foundation of loyalty/betrayal refers to the gregarious tendency of humans, which results in the species' willingness to organize itself in groups. In the face of threatening situations, a tendency of establishing a greater sense of belonging to those who are part of the community, as well as anger towards those who are external, are noted. The foundation of authority/subversion alludes to the psychological and social aspects established in hierarchical dominations. Dominance and subordination can generate feelings of respect and fear, as well as the valorization of obedience. The foundation of sanctity/degradation is the only one exclusive to human beings. The human species has developed psychological mechanisms related to disgust or distaste, which makes us more careful about what we eat. This distinction between what is pure and what is disgusting has been generalized to other symbolic contexts, constituting what is meant by "sacred" and "profane". This corroborates the valuation of aspects such as chastity and temperance as opposed to lust and intemperance (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Joseph, 2007). These three foundations make up a binding foundations in morality, as they emphasize values associated to the association of individuals to roles and duties, in order to strengthen groups and institutions (Graham et al., 2011).

The MFT tends to contribute to understanding differences in the field of politics (Graham et al., 2011; Haidt & Graham, 2007), by demonstrating that the left-wing and right-wing are guided by different moral foundations (Gloria-Filho & Modesto, 2019), favoring preferences for specific candidates (Iyer, Graham, Koleva, Ditto, & Haidt, 2010) and interfering in voting intentions (Franks & Scherr, 2015). In a study developed in Brazil, Brazilians who identify themselves as left-wing exhibit higher individualizing foundation indices (care and fairness dimensions), indicating concerns about not causing harm to other people (care) and being guided by a defense of equity (fairness) and well-being. The right, on the other hand, exhibits higher rates of a binding foundations (loyalty, authority and sanctity dimensions), i.e., greater concern with group defense (patriotism), status quo maintenance (authority) and spiritual concerns, such as religion (sanctity) (Gloria-Filho & Modesto, 2019). Such findings, according to these authors, aid in understanding political polarization in Brazil, considering that the right and the left exhibit different moral concerns, often leading to difficult dialogues between people with different political orientations.

Bearing in mind that some health field discussions permeate the political arena and the moral sphere, studies have applied MFT to understand certain phenomena, such as opinions regarding stem cell research (Clifford & Jerit, 2013) and attitudes towards programs that promote syringe exchanges (Christie et al., 2019), among others. Such studies call attention to the fact that morality can also influence the understanding of social isolation, considering that this is configured as a public health demand in a political polarization context. In this sense, as mentioned previously (H2), we believe that morality will mediate the relationship between political orientation and attitudes towards social isolation, with participants that identify more with the right presenting higher levels of binding foundations, favoring a more negative attitude towards social isolation (H2.1). On the other hand (H2.2), we believe that leftist participants will present higher indices of individualizing foundations, favoring a more positive attitude towards isolation. Despite the importance of morality in understanding the relationship between political orientation and social isolation, we believe that Fake News are also important components to be analyzed in this relationship.

Fake News

Fake News comprise inaccurate information created in a format similar to that of traditional information media, but ignoring the processes used to confirm information accuracy and credibility, as they are not structured according to editorial standards like traditional media. Fake News, in their beginning, may have had the initial intention of deceiving people, although this does not always occur (Lazer et al., 2018; Sindermann, Cooper, & Montag, 2020).

Different intra-individual and contextual variables can contribute to belief in Fake News, such as age, education and culture (Rampersad & Althiyabi, 2019), as well as political ideology. In this sense, even in the face of real-world evidence, people can rely on misinformation corresponding to variables that make up their worldviews, resisting misinformation corrections, i.e., a person's preexisting attitudes can determine, at a certain level, his/her beliefs concerning misinformation (Lewandowsky et al., 2012). As such, people tend to overestimate the accuracy of false and true political news that corroborate their own political attitudes (Sindermann et al., 2020).

The impacts of Fake News have been investigated in the Brazilian context (see Junior & Junior, 2020; Miguel, 2019), and their role in the national political arena is evident. A netnographic study identified that the 2018 presidential campaign was permeated by distorted information, and that the spread of false information was a constant in both social media and WhatsApp groups, leading to potential impacts concerning Brazilian election results (Junior & Junior, 2020).

Some strategies have been used to battle Fake News, such as fact-checkers, comprising tools that seek to confirm the accuracy of a certain news information. However, although fact-checkers exhibit the potential to correct misinformation, they partially depend on the type of issue being addressed (Hameleers & van der Meer, 2019), especially in a polarized context. These authors note that the party division between Republicans and Democrats was maintained after exposing facts about certain subjects, which suggests the presence of an affective polarization, in which people wish to reassure the positive self-concepts of their political identities. However, in a survey conducted in the American context, fact-checkers are not uniformly seen as reliable sources, where Democrats (69%) perceive that fact-checkers tend to present themselves fairly to all political parties substantially more than Republicans (28%) (Walker & Gottfried, 2019).

It is noteworthy that, in addition to the political arena, Fake News have become a serious problem due to the wide access to information promoted by the Internet, given that misinformation, fraud and conspiracy theories are abundant in digital media and are often more popular than accurate scientific information (Jamison, Broniatowski, & Quinn, 2019; Mian & Khan, 2020; Wang, McKee, Torbica, & Stuckler, 2019). All this misinformation, as warned by the World Health Organization, can impact the public health field. For example, in a study conducted in Poland, the authors note that 40% of the most shared news concerning diseases comprised Fake News (Waszak, Kasprzycka-Waszak, & Kubanek, 2018). The impacts of disinformation in vaccination discussions are also evident (Jamison et al., 2019), as narratives that vaccines cause autism, for example (Krishna & Thompson, 2019; Wang et al. 2019).

Disinformation narratives can also be observed regarding other health-related matters, such as chronic diseases, nutrition and smoking, and can often induce negative emotions, such as fear, anger, sadness and anxiety, as well as feelings of distrust (Krishna & Thompson, 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Such misinformation has hampered access to reliable information and leads to both health and well-being consequences (Hao, 2020), which seem to have increased during the pandemic.

In a context such as the current pandemic, in which no information concerning a cure, effective treatments or vaccine availability are available, fake news serve as a way to deal with the anxiety generated by uncertainties and fill this knowledge gap, promoting behaviors without any scientific criteria basis (Taylor, 2019). Taking into account different Fake News circulating in the Brazilian context, people's behavior, guided by this false information, can be either harmless, such as using water and salt to gargle (Elassar, 2020), or severe, which may lead to death, such as consuming disinfectants (Chiu, Shepherd, Shammas, & Itkowitz, 2020).

A study analyzed the influence of beliefs in Fake News on pandemic prevention behaviors (Modesto, Keller, Rodrigues, & Lopes, 2020). Through a retrospective measure, the authors identified that the endorsement of different Fake News hindered both basic hygiene behaviors and social isolation behaviors during the initial isolation period (second half of March 2020) in Brazil. Additionally, the authors identified that belief in a just world moderated this relationship. Despite the evidence noted in that study, the political positioning of the participants was not taken into account, which is relevant considering the current political polarization. Therefore, we sought to add this variable and hypothesized (H3) that Fake News will moderate the effect of political orientation on attitudes towards social isolation, where the more to the right and the more a person believes in Fake News, the more negative will his/her attitude towards isolation be.

Method

Participants

A total of 147 people participated in the study, ranging from 18 to 65 years old (M = 33.83; SD = 15.68), mostly women (78.90%), white (56.50%), with incomplete higher education level (44.20%) and family income above seven minimum wages (44.20%). Participants lived in nine of the 27 Brazilian federative units (with a prevalence of the Federal District with 64.60%). This sample size allows for a power of approximately 87% to detect an effect of R = 0.25, considering a significance level of 5%, according to GPower software estimates.

Instruments

Attitude towards social isolation. A three-item measure was created (I believe that social isolation is an appropriate tool to fight the pandemic; I have followed social isolation, leaving the house only for essential activities; I would like people close to me to follow social isolation), which should be answered on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The measure showed satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.74).

Political orientation. Individual political orientation was assessed by a single item (Indicate your political position) ranging from 1 (completely to the left) to 5 (completely to the right).

Moral foundations. The Moral Foundation Questionnaire (Graham et al., 2011) adapted to the Brazilian context (Silvino et al., 2016) was applied, composed of 27 items that must be answered on a scale of 0 to 5. The measure is categorized into two main dimensions: an individualizing foundations (harm and fairness foundations: α = 0.72) and a binding foundations (loyalty, authority and sanctity foundations: α = 0.84).

Fake News. A measure composed of three items based on Modesto et al. (2020) was created from Fake News that circulated in the Brazilian context concerning COVID-19 (drinking hot water or hot teas kill the virus; gargles are effective to fight the virus during the first days when contamination occurs; vinegar is effective in preventing coronavirus contamination). The measure presented an internal consistency index of 0.61.

Procedures

Due to social isolation recommendations, the research was carried out entirely online using the Google Forms tool. The research dissemination took place on social media and by sending the link to an e-mail database from previous studies conducted by our research team, configuring the sample as a convenience sample. When accessing the link, the participant opened an informed consent, in which the research objective was presented, indicating the risks and benefits of the study, as well as guaranteed secrecy and anonymity, among other ethical precautions. After accepting, the participant accessed political orientation, morality, Fake News and social isolation measures and informed his/her sociodemographic data. The survey was available from 4/16/2020 to 4/22/2020.

Results

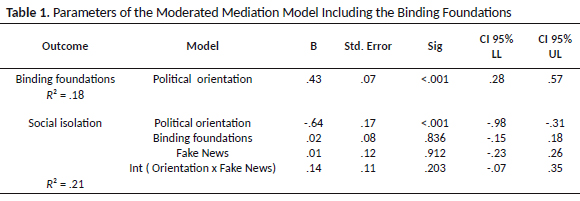

The PROCESS Model 5 in the SPSS software was used for the moderated mediation test (Hayes, 2013). The tested model is presented in Figure 1. Prior to the statistical analyses, all variables were standardized by Z scores. A first analysis consisted of inserting the binding foundations as a mediator of the relationship between political orientation and attitude towards social isolation. The results (Table 1) indicate that, the more the individual identifies with the right-wing, the higher the binding foundations indices (Path A), as expected. However, the direct relationship between political orientation and social isolation (Path C) was more robust than when the mediator (binding moral foundation) and Fake News were also taken into account. In other words, regardless of the endorsement of the binding foundations morality or belief in Fake News, it was an individual's political orientation that explained their attitude towards social isolation, indicating that, the more to the right, the more negative the attitude towards social isolation.

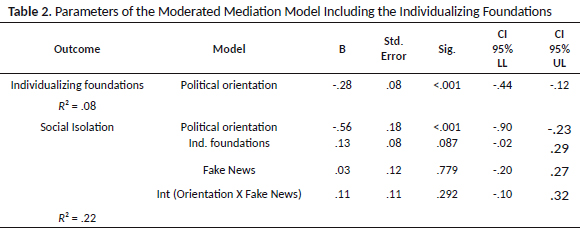

The same analytical procedure was then repeated inserting the individualizing foundations as a mediator, with similar results identified. The more to the right the individual's political position, the lower the indices of an individualizing morality (Path A), indicating that such a moral standard is typical of left-wing. Additionally, the more to the right the political orientation, the more negative the attitude towards social isolation, regardless of morality and belief in Fake News. These results are displayed in Table 2.

Discussion

This research aimed to investigate the role played by morality and belief in Fake News in the relationship between political orientation and attitude towards social isolation in Brazil. It has been proposed a moderated mediation model in which morality would mediate the relationship between political orientation and attitude towards social isolation, whereas Fake News would have a moderating effect on this relationship.

As expected (H1), political orientation interfered with attitudes towards social isolation. The more to the right the participant's political orientation, the more negative were his/her attitudes towards social isolation. Regarding the mediation effect, although political orientation influenced binding (the more to the right, the higher the value) and individualizing (the more to the right, the lower the value) moralities, the mediation effect was not corroborated (H2), indicating that political orientation has a direct effect on attitudes towards social isolation, independent of an individual's morality. On the one hand, such findings reaffirm international (Franks & Scherr, 2015; Iyer, et al., 2010; Van Leeuwen & Park, 2009; Yilmaz, Saribay, Bahçekapili, & Harma, 2016) and Brazilian (Gloria-Filho & Modesto, 2019) studies, that demonstrate that the right and left are guided by different moral foundations, which can aid in understanding political polarization. On the other hand, the findings also indicate that the attitude towards social isolation does not permeate the field of morals for Brazilians, but are, instead, a matter of political dispute.

The analysis of the moderating effect of Fake News (H3) detected similar results as the mediation test. The relationship between political orientation and social isolation (H1) was direct, with no interference from Fake News, in contrast to what was expected (H3). In this sense, regardless of whether the individual believes or not in false information concerning COVID-19, his/her political position is what explains his/her attitudes towards social isolation. This finding differs from a study conducted in Brazil during the beginning of the social isolation period, which indicated that belief in Fake News interfered with hygiene and social isolation behaviors (Modesto et al. 2020). The difference in these results can be explained by the speed with which Fake News circulates and changes. The measures applied in the present study were based on Modesto et al. (2020). However, the present data collection took place about a month later (04/16/2020 until 04/22/2020) than the data obtained by Modesto et al. (2020). One possibility is that the Fake News exhibiting greater circulation during this research period changed, which might also explain the lower internal consistency value of this study compared to that of the original measure (α = 0.71 in the original study and α = 0.61 in the present research). Therefore, we suggest that new surveys analyzing Fake News carry out more current surveys of false information concerning COVID-19, i.e., those circulating at the exact time of collection, and do not rely exclusively on previous measures, due to rapid changes in false information content.

The present study displays some limitations. In addition to the issue regarding the Fake News measure, we understand that social isolation discussions should not be restricted to an intra-individual analysis (the target of this research). Therefore, it is also necessary to consider contextual aspects, such as the conditions that the federal government and state governments have offered in terms of public policies to promote population health and guarantee population economic subsistence during the pandemic. An example is the poor management of resources and inconsistencies in positions regarding social isolation adherence and commerce closure by federal and state political representatives. This uncertainty scenario may generate greater Fake News dissemination and appropriation that do not depend on individual political positions. New research may focus on these contextual factors, allowing for macro-perspective assessments.

We believe that, despite these limitations, the present study makes several important contributions. We have highlighted how the current polarization context is becoming a public health problem, as a direct relationship between political orientation and attitude towards social isolation was identified. In this sense, it is essential that political actors, especially those on the right-wing, are attentive to World Health Organization guidelines (among other specialized bodies) and position themselves based on technical criteria, aiding in the preservation of the Brazilian population. We believe that these actors play an essential role, considering that believing in true or false information, per se, is not enough to influence isolation attitudes. In other words, it is necessary to develop governmental actions that offer conditions so that the population can, in fact, implement isolation recommendations in favor of collective well-being, despite individual orientation.

References

Borges, L. (2020, April 19). Bolsonaro fura quarentena e participa de manifestação no QG do Exército. Veja. Retrieved from https://veja.abril.com.br/politica/bolsonaro-fura-quarentena-e-participa-de-manifestacao-no-qg-do-exercito/ [ Links ]

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912-920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [ Links ]

Chiu, A., Shepherd, K., Shammas, B., & Itkowitz, C. (2020, 24 de Abril). Trump claims controversial comment about injecting disinfectants was 'sarcastic'. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/24/disinfectant-injection-coronavirus-trump/ [ Links ]

Christie, N. C., Hsu, E., Iskiwitch, C., Iyer, R., Graham, J., Schwartz, B., & Monterosso, J. R. (2019). The moral foundations of needle exchange attitudes. Social Cognition, 37(3), 229-246. doi: 10.1521/soco.2019.37.3.229 [ Links ]

Clifford, S., & Jerit, J. (2013). How words do the work of politics: Moral Foundations Theory and the debate over stem cell research. Journal of Politics, 75(3), 659-671. doi: 10.1017/S0022381613000492 [ Links ]

Do Bú, E. A., Alexandre, M. E. S., Bezerra, V. A. S.,Sá-Serafim, R. C. N., & Coutinho, M. D. L. (2020). Representações e ancoragens sociais do novo coronavírus e do tratamento da COVID-19 por Brasileiros. Estudos de Psicologia, 37, e200073. doi: 10.1590/SciELOPreprints.120 [ Links ]

Elassar, A. (2020, 17 de Março). Água com sal, dez segundos sem ar: o que não se deve fazer contra o coronavírus. CNN Brasil. Retrieved from https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/saude/2020/03/17/agua-com-sal-dez-minutos-sem-ar-o-voce-nao-deve-fazer-contra-o-coronavirus [ Links ]

Franks, A. S., & Scherr, K. C. (2015). Using moral foundations to predict voting behavior: Regression models from the 2012 U.S. Presidential Election. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 15(1), 213-232. doi: 10.1111/asap.12074 [ Links ]

Gloria Filho, M., & Modesto, J. G. (2019). Morality, activism and radicalism in the Brazilian left and the Brazilian right. Temas em Psicologia, 27(3), 763-777. doi: 10.9788/TP2019.3-12 [ Links ]

Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366-385. doi: 10.1037/a0021847 [ Links ]

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98-116. doi: 10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z [ Links ]

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2007). The moral mind: How five sets of innate intuitions guide the development of many culture- speci c virtues, and perhaps even modules. In P. Carruthers, S. Laurence, & S. Stich (Eds.), The Innate Mind (Vol. 3, pp. 367-392). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Hameleers, M., & van der Meer, T. G. L. A. (2019). Misinformation and polarization in a high-choice media environment: How effective are political fact-checkers? Communication Research, 47(2),227-250. doi: 10.1177/0093650218819671 [ Links ]

Hao, K. (2020, 17 de Fevereiro). El coronavirus en la era de las redes sociales: de epidemia a 'infodemia'. MIT Technology Review. Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.es/s/11887/el-coronavirus-en-la-era-de-las-redes-sociales-de-epidemia-infodemia [ Links ]

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications. [ Links ]

Hellewell, J., Abbott, S., Gimma, A., Bosse, N. I., Jarvis, C. I., Russell, ... Eggo, R. M. (2020). Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. The Lancet Global Health, 8(4), e488-e496. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7 [ Links ]

Iyer, R., Graham, J., Koleva, S., Ditto, P., & Haidt, J. (2010). Beyond identity politics: Moral psychology and the 2008 democratic primary. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 10(1), 293-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2010.01203.x [ Links ]

Jamison, A. M., Broniatowski, D. A., & Quinn, S. C. (2019). Malicious actors on Twitter: A guide for public health researchers. American Journal of Public Health, 109(5), 688-692. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.304969 [ Links ]

Junior, I. F. B., & Junior, G. V. (2020). Fake news em imagens: um esforço de compreensão da estratégia comunicacional exitosa na eleição presidencial brasileira de 2018. Revista Debates, 14(1), 04-25. Retrieved from https://seer.ufrgs.br/debates/article/view/96220/56872 [ Links ]

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., ... Zittrain, J. L. (2018) The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094-1096. doi: 10.1126/science.aao2998 [ Links ]

Mian, A., & Khan, S. (2020). Coronavirus: The spread of misinformation. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 1-2. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01556-3 [ Links ]

Miguel, L. F. (2019). Jornalismo, polarização política e a querela das fake news. Estudos em Jornalismo e Mídia, 16(2), 46-56. doi:10.5007/1984-6924.2019v16n2p46 [ Links ]

Modesto, J. G., Keller, V. N., Rodrigues, C. M. L., & Lopes, J. L. S. (2020). The moderating role of belief in a just world on the association between belief in fake news and prevention behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Manuscript submitted for publication. [ Links ]

Rampersad, G., & Althiyabi, T. (2019). Fake news: Acceptance by demographics and culture on social media. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 17(1), 1-11. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2019.1686676 [ Links ]

Santos, F., & Tanscheit, T. (2019). Quando velhos atores saem de cena: a ascensão da nova direita política no Brasil. Colômbia Internacional, (99), 151-186. doi: 10.7440/colombiaint99.2019.06 [ Links ]

Silvino, A. M. D., Silva, E. P., Freitas, A. F. P., Silva, J. N., Lima, M. F., Keller, V. N., & Pilati, R. (2016). Adaptação do questionário dos fundamentos morais para o Português. Psico-USF, 21(3), 487-495.doi: 10.1590/1413-82712016210304 [ Links ]

Sindermann, C., Cooper, A., & Montag, C. (2020). A short review on susceptibility to falling for fake political news. Current Opinion in Psychology. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.03.014 [ Links ]

Taylor, S. (2019). The psychology of pandemics: Preparing for the next global outbreak of infectious disease. New Castle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]

The Lancet. (2020). COVID-19 in Brazil: "So what?". The Lancet, 395(10235), 1461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31095-3 [ Links ]

Van Leeuwen, F., & Park, J. H. (2009). Perceptions of social dangers, moral foundations, and political orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(3), 169-173. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.017 [ Links ]

Walker, M., & Gottfried, J. (2019, 27 de Junho). Republicans far more likely than Democrats to say fact-checkers tend to favor one side. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/27/republicans-far-more-likely-than-democrats-to-say-fact-checkers-tend-to-favor-one-side/ [ Links ]

Wang, Y., McKee, M., Torbica, A., & Stuckler, D. (2019). Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Social Science & Medicine, 112552. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112552 [ Links ]

Waszak, P. M., Kasprzycka-Waszak, W., & Kubanek, A. (2018). The spread of medical fake news in social media–the pilot quantitative study. Health Policy and Technology, 7(2), 115-118. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2018.03.002 [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2020a, 2 de Fevereiro). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). situation report - 13. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200202-sitrep-13-ncov-v3.pdf [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2020b, 11 de Março). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). situation report - 51. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10 [ Links ]

Yilmaz, O., Saribay, S. A., Bahçekapili, H. G., & Harma, M. (2016). Political orientations, ideological self-categorizations, party preferences, and moral foundations of young Turkish voters. Turkish Studies, 17(4), 544-566. doi: 10.1080/14683849.2016.1221312

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Centro Universitário de Brasília

Campus Universitário Asa Norte

Faculdade de Ciências e Saúde

707/907 - SEPN - Asa Norte

Brasília - DF, 70790-075

Email: joao.modesto@ueg.br

Received in 09.may.20

Revised in 05.aug.20

Accepted in 15.dec.20

João Gabriel Modesto, Doutor em Psicologia Social pela Universidade de Brasília (UnB), é Professor DES IV na Universidade Estadual de Goiás (UEG), é Professor Titular do Centro Universitário de Brasília (UniCEUB).

Daniel Oliveira Zacarias, Graduando em Psicologia pelo Centro Universitário de Brasília (UniCEUB). Email: Danieloli.zac@gmail.com

Luccas Moraes Galli, Graduando em Psicologia pelo Centro Universitário de Brasília (UniCEUB). Email: galliluccas@gmail.com

Beatriz do Amaral Neiva, Graduanda em Psicologia pelo Centro Universitário de Brasília (UniCEUB). Email: beatriz.neiva1@gmail.com