Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Temas em Psicologia

versão impressa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.24 no.4 Ribeirão Preto dez. 2016

https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.4-18

ARTIGOS

A possible dialogue between analytical psychology and complementary and alternative medicine

Um possível diálogo entre a psicologia analítica e a medicina alternativa e complementar

Un diálogo posible entre la psicología analítica y la medicina alternativa y complementaria

Pamela SiegelI; Egberto Ribeiro TuratoII

IDepartment of Collective Health of State University of Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil

IIDepartment of Medical Psychology and Psychiatry of State University of Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to present the results of an integrative literature review of Analytical Psychology linked to complementary and alternative medicine. The objective of the study was to find out if there is any evidence that C. G. Jung or his followers integrated Analytical Psychology and Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in their practice.

BACKGROUND: Analytical Psychology was thriving when the roots of counter–culture movements and alternative medicine were beginning to gain momentum in the West.

METHODS: data sources MEDLINE and Psychological Abstracts were searched using the

KEYWORDS: alternative medicine; complementary and alternative medicine; integrative medicine; complementary therapies; acupuncture; homeopathy; yoga; healing. These terms were linked firstly with Carl Gustav Jung and then with Analytical Psychology. The search strategy was not limited to specific languages or time spans and the integrative review of the studies was conducted over a 6-month time period in 2013.

RESULTS: the search yielded 10 publications on mandalas; music; kundalini yoga; mindfulness; homeopathy, I Ching; Shamanism; Daoism; biofeedback and traditional healing rituals. In conclusion, despite the use of CAM by some of Jung's followers, Jung was dedicated to understanding the healing mechanism from the psychic perspective and there is no evidence that he integrated body-mind or other CAM techniques, like breathing, stretching, herbal treatment, dieting and fasting, homeopathy and acupuncture, into his clinical practice, although he himself practiced yoga for a short period. Nevertheless, there is no evidence that he recommended yoga to his patients.

Keywords: Analytical Psychology, psychotherapy, Complementary and Alternative Medicine, yoga, integrative literature review, Carl G. Jung.

RESUMO

O propósito deste estudo é apresentar os resultados de uma revisão integrativa da literatura sobre Psicologia Analítica relacionada à Medicina alternativa e complementar (MAC).

OBJETIVO: identificar se há evidências de que C. G. Jung ou seus seguidores integraram a Psicologia Analítica com MAC em suas práticas.

CONTEXTUALIZAÇÃO: a Psicologia Analítica estava em pleno desenvolvimento quando as raízes dos movimentos de contracultura e a medicina alternativa ganhavam impulso no ocidente.

MÉTODOS: as buscas foram realizadas em 2013 nas bases de dados MEDLINE e Psychological Abstracts com as seguintes

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: medicina alternativa; medicina alternativa e complementar; medicina integrativa; terapias complementares; acupuntura; homeopatia; yoga; cura, e cruzados com Carl Gustav Jung e Psicologia Analítica.

RESULTADOS: as buscas resultaram em 10 publicações sobre mandalas, música, kundalini yoga, mindfulness, homeopatia, I Ching, xamanismo, taoísmo, biofeedback e rituais de cura tradicionais.

CONCLUSÃO: apesar de alguns seguidores de Jung usarem MAC, Jung estava dedicado à compreensão do mecanismo de cura a partir da perspectiva psíquica, e não há evidências de que tenha integrado técnicas mente-corpo ou outras MAC, como respiração, alongamentos, tratamento com plantas medicinais, dietas, jejuns, homeopatia, acupuntura, em sua prática clínica, embora ele tenha praticado yoga por um curto período de tempo.

Palavras-chave: Psicologia Analítica, psicoterapia, Medicina alternativa e complementar, yoga, revisão integrativa de literatura, Carl G. Jung.

RESUMEN

PROPÓSITO: presentar los resultados de una revisión integrativa de la literatura que abarca la Psicología Analítica relacionada a la Medicina alternativa y complementaria (MAC).

OBJETIVO: identificar si hay evidencias de que C. G. Jung o sus seguidores han integrado la Psicología Analítica con MAC en sus prácticas clínicas.

CONTEXTUALIZACIÓN: la Psicología Analítica se encontraba en pleno desarrollo mientras que las raíces de los movimientos de contracultura y las MAC florecían en el occidente.

MÉTODOS: fueron realizadas búsquedas, en 2013, en las bases de datos MEDLINE y Psychological Abstracts utilizando las siguientes

PALABRAS-CLAVE: medicina alternativa; medicina alternativa y complementaria; medicina integrativa; terapias complementarias; acupuntura; homeopatía; yoga; cura, entrecruzándolos con Carl Gustav Jung y con Psicología Analítica.

RESULTADOS: fueron encontradas 10 publicaciones sobre mandalas, música, kundalini yoga, mindfulness, homeopatía, I Ching, chamanismo, taoismo, biofeedback y rituales tradicionales de cura.

CONCLUSIÓN: aunque algunos seguidores de Jung han utilizado MAC, Jung estaba dedicado a la comprensión del mecanismo de cura partiendo de la perspectiva psíquica, y no hay evidencias de que él tenga integrado técnicas mente-cuerpo u otras MAC, como respiración, estiramientos, tratamiento herbolario, dietas, ayunos, homeopatía y acupuntura, en su práctica clínica, si bien ha practicado yoga durante un corto período de tiempo.

Palabras clave: Psicología Analítica, psicoterapia, Medicina alternativa e complementaria, yoga, revisión integrativa de la literatura, Carl G. Jung.

More often than not psychotherapy appears linked to Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM). Hoge et al. (2013) affirm that mindfulness meditation may have a beneficial effect on anxiety symptoms in generalized anxiety disorder and may also improve stress reactivity and coping as measured in a laboratory stress challenge. Franz et al. (2013) suggest that clinicians dealing with refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) patients should, among other options, consider non-conventional pharmacological approaches and non-conventional psychotherapeutic approaches. Sylvia, Peters, Deckersbach, and Nierenberg (2012) consider that adjunct treatments which improve psychiatric as well as physical health outcomes, such as nutritional treatments, appear promising for the management of bipolar disorder.

Manzaneque et al. (2009) suggest that the practice of qigong promotes a positive effect on psychological well-being after one month training.

Interestingly, Kaplan, Sadock, and Sadock (2007), in their Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, did include a whole chapter on CAM in Psychiatry. They mention Engel's biopsychosocial model, which aims to take into consideration patients' biological, psychological and social factors, treating them with a holistic approach. However, in the national health systems using CAM and following the World Health Organization (WHO) strategies (2013), there is no clear theoretical framework indicating a triangulation of biomedicine-CAM-mental health. The WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy states that Traditional Medicine (TM) is "used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness" (WHO, 2013,p. 16) and that "Traditional Chinese Medicine (T&CM) practices include medication therapy and procedure-based health care therapies ... and other physical, mental, spiritual and mind-body therapies" (WHO, 2013, p. 32).

In April 2013, though, the American Psychological Association (APA) published the "CE Corner", a quarterly continuing education article, providing its readers with updates on the use of CAM (Barnett & Shale, 2013). The following alternative techniques were mentioned: dietary supplements, meditation, chiropractic, aromatherapy, massage therapy, yoga, progressive muscle relaxation, spirituality/religion and prayer, movement therapy, acupuncture, reiki, biofeedback, hypnosis and music therapy, along with ethical issues and boundary concerns for psychologists.

Analytical Psychology was constructed upon Carl G. Jung's psychotherapeutic approach towards the person's development and experiences, which he called the process of individuation. The analytical process deals with concepts such as the self, persona, ego, shadow, complex, synchronicity, anima and animus. It involves the representation of symbolic experiences in human life and the exercise of shedding light onto personal and collective unconscious factors, the archetypes (Cambray & Carter, 2004).

Analytical Psychology (AP hereafter) was thriving when the roots of counter-culture movements and alternative medicine, meaning the use of a non-mainstream approach in place of conventional medicine, were beginning to gain momentum in the West. After the seventies, health professionals sought to combine alternative and conventional techniques, and CAM came into focus. CAM is used together with conventional medicine, although complete integration is called integrative medicine. CAM deals with natural products, such as herbs and dietary supplements; mind-body practices, massage and movement therapies; energetic therapies, reiki, therapeutic touch, and whole systems, Ayurvedic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, homeopathy and naturopathy (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine [NCCAM], 2008). More recently the National Institutes of Health, under the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), has switched to the term Complementary Health Approaches (2015).

Giglio (1997) compares the Buddhist philosophy to the Jungian theory of synchronicity, according to which everything in the universe is linked not only by causal relations, but also by non-causal ones. And he goes further to affirm that, in this aspect, Jung was the precursor of the holistic movement, which has influenced many fields of thought such as education, psychology, medicine and ecology.

Many academics envisage myths as keys to the human soul, symbolic passages to our most profound individual and collective nature. Goffman and Joy (2007) have stressed the relevance of mythology in the eyes of contemporary psychologists, anthropologists and historians, among which Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell were world famous. Broad (2012) mentions that Jung pioneered the academic study of kundalini, the yogic state characterized by strong body currents and that, in 1938, he warned that the experience could result in madness. According to Kennedy and Ryan (1998/2003) the counter-cultural movement begins in Ascona, where several life experiments such as surrealism, modern dance, dada, paganism, feminism, pacifism, psychoanalysis and nature cure were in vogue at the Mountain of Truth. Besides Jung, a few of the participants were Hermann Hesse, Isadora Duncan, D. H. Lawrence, Arnold Ehret and Franz Kafka, Dr. Benedict Lust and German psychedelic painter Fidus. Some of the values and life style trends practiced there were linked to the concept of Lebensreform (life-reform) used at the end of the 19th and first half of the 20th century and included: nudism, vegetarianism, natural medicine, garden towns, health food and economic reform, soil reform and sexual reform. In the year 1900 a counter-culture renaissance began in Ascona and lasted until about 1920. The little fishing village, with its beautiful natural landscapes, inspired urban people to hike and fast, experiment raw food diets, and became a meeting point for all of Europe's spiritual rebels, influencing Gandhi and setting a base for ecology, organic farming, youth hostel movements and naturopathy.

So, in this scenario, Jung seemingly was a challenging pioneer for the holistic movement worldwide, who practiced yoga and astrology besides his clinical activities and embraced mythology and oriental traditions. What the authors of this paper wanted to find out is if Jung or his followers, having studied oriental systems of thought, also approached their health systems, if they encourage their patients to use CAM, or even if they integrate CAM into their analytical work. The purpose of this paper is to present the results of an integrative literature review of analytical psychology linked to complementary and alternative medicine.

Design and Search Method

The Integrative Literature Review (ILR) is a planned process of identification and selection of scientific studies which contributes to the evaluation and interpretation of the data found therein. Its purpose is to synthesize the studies' results on a certain theme, be it a conceptual definition, a methodological analysis or a review of theories.

In ILR, the decision-making is based on the application of procedures to a certain health practice, showing conflicting and/or coinciding results, as well as the limitations and evidence of these studies and it entails six steps: (a) the identification of the theme or question to be investigated; (b) the construction of exclusion/inclusion criteria for the articles; (c) the definition of the information to be extracted from the selected articles; (d) the evaluation of the included articles; (e) the interpretation of the results, and (f) synthesis of knowledge (Mendes, Silveira, & Galvão, 2008; Sampaio & Mancini, 2007). As regards to step (a), the theme was to find out if and how AP and CAM were linked and shared common ground. So step (b) consisted of the following search strategy: MEDLINE and Psychological Abstracts were searched using the Keywords: alternative medicine; complementary and alternative medicine; integrative medicine; complementary therapies; acupuncture; homeopathy; yoga; healing. These terms were linked firstly with Carl Gustav Jung (CGJ hereafter) and then with Analytical Psychology. Lastly, Jungian Psychology and mindfulness was searched for in both databases, so the totality of combinations added up to 17.

The inclusion criteria, therefore, consisted of articles mentioning both one type of CAM and AP or CGJ. The exclusion criteria referred to articles that mentioned either AP/CGJ or CAM. The search strategy was not limited to specific languages or time spans and the integrative review of the studies was conducted over a 6-month time period in 2013. A new and identical search was performed in November 2015, in the same databases, and no new papers on the subject were found.

Concerning step (c) the definition of the information to be extracted from the selected articles, the purpose was to identify if and how CAM was intertwined with AP, the circumstances and the possible outcomes.

Step (d) is presented in the section "Results" and step (e) and (f) in sections Discussion/Conclusion.

Results

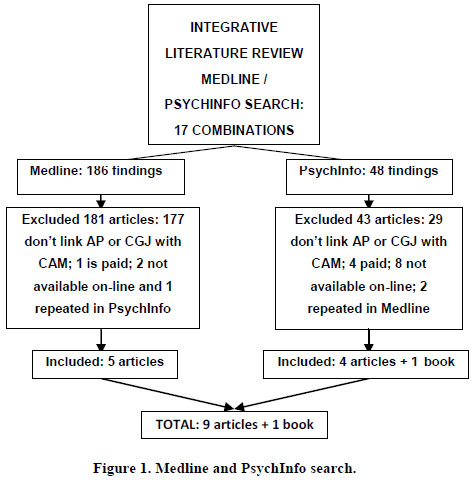

Using the above-mentioned search criteria 234 references were retrieved, among which 224 were excluded. Among those, 206 did not link AP or CGJ with CAM; five articles had to be paid for and the State University of Campinas/Brazil, to which the authors of this paper belong, doesn't subscribe to those journals; 10 articles were not available on-line as full-texts, of which four were dissertations; and three were repeated in both databases. Only nine articles and one book met the inclusion criteria. The following Figure 1 illustrates the outcomes:

Coming back to step (d) of the ILR, the evaluation of the included articles, the 10 studies included were read from beginning to end in their full version and, as regards the type of article, one is a literature review itself. It is noteworthy that all studies but one use qualitative methodology, all were written in English and published between 1986 and 2009. Five articles were published in the Journal of Analytical Psychology and three appear in journals which are not specific for AP: Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts; Psychoanalytic Psychology and Holistic Nursing Practice. The latter is the only journal not directly associated with the psychological field and is closer to CAM. Moreover, it is important to emphasize that only one reference stems directly from CGJ himself, which is the book The Psychology of Kundalini Yoga.

The list of the selected studies is presented in Table 1.

Discussion

Concerning the interpretation of the results mentioned in step (e), the outcomes are mixed. According to the authors of the selected articles, there is no absolute consensus about the concepts and practices of healing in analytical psychology as described by Jung. On one hand, for instance, according to Whitmont (1996), homeopathy deals with "transmaterial principles as a priori constituents of matter", which Jung could not come to terms with, therefore he tried to explain the alchemist's procedures in terms of "projections upon matter which needed to be taken back and be recognized exclusively as aspects of the human psyche" (Whitmont, 1996, p. 6). Furthermore, Whitmont affirms that complementary modalities (e.g.complementary therapies) such as bioenergetics, acupuncture, art therapy, should be combined with AP to modify what he called the pathology of the psychoid.

Boechat (2008) retrieves Jung's concept of the psychoid archetype related to the mind-body wholeness. Bleuler had used the term as a noun to signify a region of the central nervous system which is responsible for the establishment of phenomena of apparent psychic origin, being the phenomena in fact of central origin. Jung used the expression in a different setting, as an adjective, meaning a characteristic of all archetypes which are always psychoid, that is, almost psychic and, at the same time, almost material, situated at a frontier region between psyche and matter. This concept highlights both Bleuler's and Jung's concern with the mind-body phenomenology. Later, after the studies on synchronicity were performed, the notion of the psychoid was extended to the limits of matter in general. The psychoid characteristic of the archetype is fundamental for a comprehensive mind-body approach, because only synchronicity can explain certain psychosomatic phenomena which cannot be understood by a causal perspective.

Zhu (2009) postulates that, according to Cleary (1991), R. Wilhelm's version of the Daoist text, Secret of the Golden Flower, which Jung had read, was a later text than was firstly acknowledged and that it had been corrupted. He also points out that Jung missed the point when he tried to draw a parallel between the Western unconscious and states of higher consciousness in Eastern meditation practices.

On the other hand, Ma (2005), in her clinical work, integrates physical exercises, healing sound, visualization and breathing techniques with psychology work, and she believes that it is possible to equate the Chinese notion of Tao with Jung's concept of the unus mundus, the unity of existence which underlies the duality of psyche and matter.

Interestingly, although Jung was conscious of the mind-body functioning he did not incorporate any mind-body practices into his clinical work, although he himself practiced yoga for a while. Yet mind-body exercises were frequently used by his followers. Farah (1995) quotes most of Jung's excerpts on the body and the anatamophysiological structures and processes. She integrated Pethö Sándor's calatonia technique and Reichian perspectives into her clinical work. Zimmermann (1996) used meditative dance and sand play as an experiment to help integrate symbolic processes. Sassenfeld (2008) stresses the need for a balance between the psychological and bodily side to attain completeness in analytical psychology.

We agree with Sassenfeld (2008, p. 16) when he mentions Heuer: "one of the goals of Jungian psychotherapy is touching the soul, but he notices that this formulation, though cast in a bodily metaphor, largely leaves the body out".

Two of the selected articles deal with specific therapeutic techniques, such as the drawing of mandalas by children who suffer from PTSD (Henderson et al., 2007) and the use of music therapy (McClary, 2007). In both cases, the authors are convinced that the applied techniques allow for patients to access a symbol making process which alleviates trauma and promotes wellness. Likewise, Koss (1986) presents a comparative study in which he equates a Puerto Rican spiritist ritual drama with analytical psychology in the sense that both fulfill the objectives of promoting the dialogue with inner self. Many spiritist venues also offer purifying herbs baths and spiritual blessings to cleanse the being of possessive spirits. Here the difference in comparison to the two former articles is that they work with artistic and more culturally neutral resources whereas Koss's study is bound to a religious setting. Interestingly, it seems that different paths can achieve the same results.

Maaske's (2002) study on spirituality and mindfulness is somewhat similar to Bonadonna's (2003) on meditation, except that the former is purely theoretical and binds together shamanistic traditions and contemporary trends in psychoanalysis; human longing for transcendence; and psychoanalysis and meditative traditions, emphasizing that "psychoanalysis sees only a regressive merger that is negative in light of the goal of psychic autonomy, where spiritual and relational traditions see positive transcendence that does not preclude healthy ego functioning but rather informs it". (Maaske, 2002, p. 4). Some may argue that Maaske's article is not specific enough about AP and CAM, but it was included because it helps to articulate the issues of symbolization, institutional religion and the personal experience of spirituality, which are core experiences for many CAM users. Bonadonna focuses on meditation as a CAM intervention in the health field, in chronic illness, and describes Zen Buddhist meditation, transpersonal psychology and Wilber's concept (2000) of the spectrum of consciousness, underscoring the importance of consciousness in the healing process. The author likens the Jungian individuation process to the Eastern process of meditation, although we could probably equate Jung's active imagination practice to Eastern meditation, with the difference that the former encourages the meditator to get in touch with the images and establish a meaning about them, whereas in the latter, the mind flows beyond the images which pop up and is steadily bound to the breath and/or a specific deity or chakra.

Groesbeck (1989) illustrates how Jung acted according to a shamanic archetype, giving practical examples of his biography, and already in the eighties he expressed his worries about the divisions of what he coined as the modern, priestly, medical and true Jungians. He considers the latter the ones who function as shamans and "produce a transformational healing experience" (Groesbeck, 1989, p. 20).

Lastly but not least, the book The Psychology of Kundalini Yoga (Jung & Shamdasani, 1996) deserves some comments. What Jung does all through his lectures which comprise this book is try to find common ground between Tantric Yoga and alchemistic philosophy, especially when he mentions the transformation of gross matter into the subtle matter of the mind. The specific passage # 110 (Lectures 3 and 4, p. 10) referring to the fifth chakra visuddha illustrates Jung's conviction when he says: "in visuddha the whole game of the world becomes your subjective experience. The world itself becomes a reflection of the psyche". Here he leaves no door open for the concept of a pre-existing and independent world a priori. Moreover, when Jung mentions the last chakra sahasrara, he affirms it is "beyond any possible experience", "it is nirvana" and that it "is an entirely philosophical concept" and "is without practical value for us" (Paragraph 129 - Lectures 3 and 4, p. 17). So if Tantric Yoga apparently is equivalent to the alchemistic approach and analytical psychology to the latter, in some ways, the end product for individuation would be a state hard to define. The closest we would get to it would be liberation, a release from suffering and a prior state of bondage. In this sense, there is a question that remains unanswered: is the analytical process of delving into the unconscious and trying to integrate unconscious symbols to consciousness the same as to climb up the seven-step-chakraladder of kundalini? This question echoes Zhu's postulation (2009) about Jung equating the Western unconscious with states of higher consciousness in Eastern meditation practices already mentioned in this paper.

For some psychologists, including the spiritual or religious factor in psychotherapy or treatment could be a problem, nevertheless for Jung it was an inherent part of the human psyche. Monteiro (2004) argues that spirituality is a particular attitude experienced by a numinous perception, which doesn't necessarily refer to a specific religion. The spiritual dimension, therefore, is a natural manifestation of the psychic energy and does not depend on a priest, rabbi, imam or guru. The author recommends using each patient's spirituality to motivate him/her in their treatment and especially help them cope with the death phase and understand the symbolic meaning of passing away. Bekke-Hansen et al. (2014) found some degree of religious and spiritual faith among acute coronary syndrome patients living in a secularized society. Although some authors may argue that the Western world has become more secular, and that religion, health and mental health should not be combined, Cipriani (2004), citing Danièle Hervieu-Léger, affirms that secularization is a myth, and that religion continues to sprout in a post-traditional format, in the New Religious Movements, and in what she calls emotional communities, elective brotherhoods and ethno-religions. Dalgalarrondo (2008) studied the relationship between religion, psychopathology and mental health in the Brazilian society and concluded that, although in most cases religion has a positive outcome and brings meaning to suffering and life, it can be both positive and negative for mental health, providing either liberation or imprisonment. Furthermore, the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) recently approved the "WPA Position Statement on Spirituality and Religion" suggesting that psychiatrists be trained to understand the role of religion and spirituality in the treatment of psychiatric disorders (2015).

As regards the strengths and weaknesses of this paper, under the former point we can mention that it is a relatively new topic, so not much is known about it. What it adds is the possibility of opening up a discussion about similarities and differences between analytical psychology and complementary and alternative medicine and how integrating them could be effective in some cases.

Possible weaknesses are: the search was undertaken only in two databases and the number of articles included is small. Nevertheless, when searching in the broader field of Psychotherapy and Complementary and Alternative Medicine or Alternative Medicine, in the same databases used in this study, many more options surface.

Nagakawa and Ikemi (1982) back in 1982 had already presented a model for the integration of Western and Eastern approaches. Park (2013) argues that the integration of mind-body CAM interventions into clinical health psychology can be useful for researchers, practitioners and policy makers. Furthermore, Harris and Thirlaway (2015) defend the use of psychosocial models and methods to evaluate CAM.

Ventegodt (2007) discusses the fact that holistic medicine, which seems to be safer, more efficient, and cheaper, is recommended also to be used as treatment for mental illness. Fritzsche et al. (2011) studied patients with medically unexplained symptoms in China and found that, from a biopsychosocial perspective, various treatment approaches can be effective depending on the patient's complaints, his illness beliefs, and what the physician offers. Kutch (2011) even presents a cost-effectiveness analysis of complementary and alternative medicine in treating mental health disorders. Lees (2011) argues for the cross-fertilization of ideas between therapists using counseling and psychotherapy, and health professionals applying CAM. Furthermore, Lees exemplifies how this integrative approach could function, by presenting a study case related to anthroposophic psychotherapy. Although the author acknowledges that his methodology is insufficient for nailing down any conclusions, he admits that "the research should be viewed as providing a tentative hypothesis which is aimed at inviting the expression of alternative voices or perspectives and as a precursor for further research" (Lees, 2013, p. 13).

Like Newtonian and Quantum physics, in psychology and the healing field there is not one theory that can embrace all possibilities. It is well known that one kind of psychotherapy alone cannot cure all kinds of patients. Concepts and practices such as Integrative Psychology promoted by The Center for Integrative Psychology (2014), Integrative Psychotherapy (Norcross & Goldfried, 2005), Integral Psychology (Wilber, 2000) are attempts to expand and combine different approaches in mental health, and the American Psychiatric Association has been publishing newsletters on its website, on CAM, since 2005 (2015). Furthermore, Positive Psychology has developed in the last few years and uses mindfulness as a useful therapeutic tool (Cebolla, García-Campayo, & Demarzo, 2014).

In the national scenario, Núcleo Anthropos (Núcleo de Integração, Mente, Corpo e Espiritualidade, 2000) is a Brazilian research group linked to the Department of Psychiatry of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), whose mission is to study the possibilities of interaction between mind, body and spirituality. No articles were found on the group's web-site specifically on AP and CAM, however one of its founding members has done research on personality development integrating the perspectives of Analytical Psychology and Taoism (Bloise, 2002). The Department of Psychiatry at UNIFESP also harbors a centre for research on Mindfulness. Furthermore, it is noteworthy to mention NUMEPI (http://www.unifesp.br/reitoria/proex/acoes/nucleos-associados/numepi), which stands for Nucleus of Medicine and Integrative Practices, dedicated to the research of whole systems and Complementary Health Approaches, according to the National Policy for Integrative and Complementary Practices, established in 2006 and applied to the national health system. However, no specific material on AP and CAM has been produced sofar. Lastly, LAPACIS (http://www.fcm.unicamp.br/fcm/lapacis), the laboratory for alternative, complementary and integrative practices in health, linked to the Collective Health Department of the State University of Campinas, is in touch with the Regional Psychology Council (Conselho Regional de Psicologia - São Paulo [CRP-SP]) building a cooperation in research. The CRP has been promoting a series of seminars introducing debates on the frontiers of psychology and traditional knowledge, as well as psychology and non-hegemonic epistemologies (CRP-SP, 2015).

A field where AP and CAM could converge is Health Psychology, which dates back to the nineteen seventies, when Matarazzo (1980) defined it as a set of specific scientific, educational and professional contributions to the field of Psychology for health promotion and prevention, and the identification of the etiology and health diagnosis, as well as the improvement of healthcare systems and policies. However, in the articulation of biomedicine and CAM (NCCAM, 2008), Health Psychology and mental health were not directly involved.

A possible dialogue between CAM and psychology, and specifically Analytical Psychology, can bring about a debate not only in the health field but also in the field of the sociology of professions, where professional jurisdictions and the conflicts between professions are brought under the spotlight. Many new elements like the outsourcing of the economic activity, the adaptability and permanent availability of professionals, the feminization of more and more professions, stronger competition between professionals, foreign investment, the globalization of markets and the importance of consumer satisfaction have been framing the professional activities since the 1990s (Saks & Lee-Treweek, 2005).

Final Considerations

Through the selected studies we presented in this integrative literature review some non-conventional and CAM practices were identified linked to AP: mandalas; music; kundalini yoga; mindfulness; homeopathy, I Ching; Shamanism; Daoism; biofeedback and traditional healing rituals. We can infer that Jung was specifically dedicated to understanding the healing mechanism from the psychic perspective. There is no evidence that he discussed the use of Complementary Health Approaches, like breathing, body-practices, herbal treatment, dieting and fasting, homeopathy and acupuncture, with his patients or recommended them, although it is known that he himself practiced yoga for a period. Although he was familiar with the Chinese and Hindu Traditions, which both comprise traditional medical systems, apparently he was mostly interested in corroborating his findings and comparing Eastern spiritual techniques with his Western created ideas, in a conceptual dimension. He focused on how the psyche affected the body more than the other way round. Moreover, it seems that he didn't consider the mindbody dimension as a dual venue for the healing process, as the Asian medical systems did. Nevertheless, it must be said that his vision of the individuation process would encompass any kind of traditional medicines, whole systems and mind-body practices and that, as we have seen, some contemporary analysts do already integrate different approaches.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2015). Integrative Medicine. Retrieved from http://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professionalinterests/integrative-medicine [ Links ]

Barnett, J. E., & Shale, A. J. (2013). Alternative techniques. Monitor on Psychology, 44(4),48. [ Links ]

Bekke-Hansen, S., Christina, G., Pedersen, C. G., Thygesen, K., Christensen, S., & Walede L. C. (2014). The role of religious faith, spirituality and existential considerations among Heart patients in a secular society: Relation to depressive symptoms 6 months post acute Coronary syndrome. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(6),740-753. doi:10.1177/1359105313479625 [ Links ]

Bloise, P. V. (2002). O desenvolvimento da personalidade na perspectiva da Psicologia Analítica e Taoísta (Doctoral dissertation, Departamento de Psiquiatria, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP, Brazil). [ Links ]

Boechat, W. (2008). O sonho em pacientes somáticos [Dreams in somatic patients]. Cadernos Junguianos, 4. [ Links ]

Bonadonna, R. (2003). Meditation's impact on chronic illness. Holistic Nursing Practice, 17(6),309-319. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14650573 [ Links ]

Broad, W. J. (2012). The science of yoga. The risks and the rewards. New York: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Cambray, J., & Carter, L. (2004). Analytical Psychology. Contemporary perspectives in Jungian Analysis. In K. Tudor (Series Ed.), Advancing theory in therapy. New York: Brunner-Routledge. [ Links ]

Cebolla, A., García-Campayo, J., & Demarzo, M. (2014). Mindfulness y ciencia, de la tradición a la modernidad [Mindfulness and science, from tradition to modernity]. Madrid: Alianza. [ Links ]

Cipriani, R. (2004). Manual de Sociología de la Religión [Handbook of Sociology of Religion]. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno. [ Links ]

Conselho Regional de Psicologia - São Paulo. (2015). Seminários estaduais. Na fronteira da psicologia com saberes tradicionais. Psicologia, espiritualidade e epistemologias não-hegemônicas. Retrieved from http://crpsp.org.br/eventosdiverpsi/seminario3.aspx [ Links ]

Dalgalarrondo, P. (2008). Religião, Psicopatologia & Saúde mental [Religion, Psychopathology & Mental Health]. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. [ Links ]

Farah, R. M. (1995). Integração psicofísica. O trabalho corporal e a psicologia de C. G. Jung [Psychophysical integration. Body work and the psychology of C. G. Jung]. São Paulo, SP: Robe. [ Links ]

Franz, A. P., Paim, M., Araújo, R. M. de, Rosa, V. de O., Barbosa, Í. M., Blaya, C., & Ferrão, Y. A. (2013). Treating refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: What to do when conventional treatment fails? Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 35(1),24-35. doi:10.1590/S223760892013000100004 [ Links ]

Fritzsche, K., Xudong, Z., Anselm, K., Kern, S., Wirsching, M., & Schaefert, R. (2011). The treatment of patients with medically unexplained physical symptoms in China: A study comparing expectations and treatment satisfaction in psychosomatic medicine, biomedicine, and traditional Chinese medicine. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 41, 229-244. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22073762 [ Links ]

Giglio, J. (1997). Psicoterapia e espiritualidade [Psychotherapy and spirituality] [Monograph]. São Paulo, SP: Jungian Association of Brazil. [ Links ]

Goffman, K., & Joy, D. (2007). Contracultura através dos tempos. Do mito de Prometeu à Cultura Digital [Counterculture through time. From the myth of Prometheus to digital culture]. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Ediouro. [ Links ]

Groesbeck, C. J. (1989). C. G. Jung and the shaman's vision. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 34,255-275. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2670864 [ Links ]

Harris, P., & Thirlaway, K. (2015). Using Psychosocial Models and Methods to evaluate Complementary and Alternative Medicine. In M. J. Langweiler & P. W. McCarthy, Methodologies for effectively assessing Complementary and Alternative Medicine. London: Jessica Kingsley. [ Links ]

Henderson, P., Rosen, D., & Mascaro, N. (2007). Empirical study on the healing nature of mandalas. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1,148-154. doi:10.1037/19313896.1.3.148 [ Links ]

Hoge, E. A., Bui, E., Marques, L., Metcalf, C. A., Morris, L. K., Robinaugh, D. J., ...Simon, N. M. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: Effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74,786-792. doi:10.4088/JCP.12m08083 [ Links ]

Jung, C. G., & Shamdasani, S. (Eds.). (1996). The psychology of Kundalini yoga: Notes of the seminar given in 1932 by C. G. Jung (Bollingen series, No. 99). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Kaplan, H. I., Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. A. (2007). Compêndio de psiquiatria: Ciência do comportamento e psiquiatria clínica [Handbook of Psychiatry: The science of behavior and clinical psychiatry] (9th ed.). Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. [ Links ]

Kennedy, G., & Ryan, K. (2003). Hippie Roots & The Perennial Subculture. Based on Kennedy G. Children of the Sun. (Excerpts reprinted from Children of the Sun; A Pictorial Anthology From Germany To California, 1883-1949, by G. Kennedy, Ed., 1998, Ojai, CA: Nivaria Press). Retrieved from http://www.hippy.com/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=243 [ Links ]

Koss, J. D. (1986). Symbolic transformations in traditional healing rituals: Perspectives from analytical psychology. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 31,341-355. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2429948 [ Links ]

Kutch, M. D. (2011). Cost-effectiveness analysis of complementary and alternative medicine in treating mental health disorders. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 71,11-A, 4102. [ Links ]

Lees, J. (2011). Counselling and psychotherapy in dialogue with complementary and alternative medicine. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 39,117-130. doi:10.1080/03069885.20 10.547051 [ Links ]

Lees, J. (2013) Psychotherapy, complementary and alternative medicine and social dysfunction. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 15,201-213. doi:10.1080/13642537.2013.810658 [ Links ]

Ma, S. S. (2005). The I Ching and the psyche-body connection. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 50,237-250. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15817045 [ Links ]

Maaske, J. (2002). Spirituality and mindfulness. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 19,777-781. doi:10.1037/0736-9735.19.4.777 [ Links ]

Manzaneque, J. M., Vera, F. M., Rodriguez, E. M., Garcia, G. J., Levya, L., & Blanca, M. J. (2009). Serum Cytokines, mood and sleep after a Qigong Program. Is Qigong an effective psychobiological tool? Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1),60-67. doi:10.1177/1359105308097946 [ Links ]

Matarazzo, J. D. (1980). Behavioral Health and Behavioral Medicine. American Psychologist, 35,807-817. [ Links ]

McClary, R. (2007). Healing the psyche through music, myth, and ritual. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1,155-159. doi:10.1037/1931-3896.1.3.155 [ Links ]

Mendes, K. D. S., Silveira, R. C. C. P., & Galvão, C. M. (2008). Revisão integrativa: Método de pesquisa para a incorporação de evidências na saúde e na enfermagem [Integrative review: Research method for the incorporation of evidence in health and nursing]. Texto Contexto - Enfermagem, 17,758-764. doi:10.1590/S010407072008000400018 [ Links ]

Monteiro, D. M. R. (2004). Espiritualidade e envelhecimento [Spirituality and aging]. In L. Py, J. L Pacheco, & A. Z. Bassit (Eds.), Tempo de Envelhecer: Percursos e dimensões psicossociais (pp. 159-181). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Nau. [ Links ]

Nagakawa, T., & Ikemi, Y. (1982). A new model of integrating Occidental and Oriental approaches. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 26(1),57-62. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7062302 [ Links ]

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. (2008). Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: What's in a name? Retrieved from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam [ Links ]

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2015). Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What's in a name? Retrieved from https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrativehealth [ Links ]

Norcross, J. C., & Goldfried, M. R. (2005). Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration: Oxford Series in Clinical Psychology (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Núcleo de Integração, Mente, Corpo e Espiritualidade, Department of Psychiatry, Federal University of São Paulo. (2000). Histórico e atividades atuais. Retrieved from http://www.nucleoanthropos.com/site/quem-somos/historico.html [ Links ]

Park, C. (2013). Mind-body CAM interventions: Current status and considerations for integration into clinical health psychology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1),45-63. doi:10.1002/jclp.21910 [ Links ]

Saks, M., & Lee-Treweek, G. (2005). Political power and professionalisation. In G. Lee-Treweek, T. Heller, H. MacQueen, J. Stone, & S. Spurr (Eds.), Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Structures and safeguards (pp. 75-100). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sampaio, R. F., & Mancini, M. C. (2007). Estudos de Revisão Sistemática: Um guia para síntese criteriosa da evidência científica [Studies on Systematic Review: A guide for a judicial synthesis of scientific evidence]. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 11(1),83-89. doi:10.1590/S1413-35552007000100013 [ Links ]

Sassenfeld, A. (2008). The Body in Jung's Work: Basic Elements to Lay the Foundation for a Theory of Technique. The Journal of Jungian Theory and Practice, 10(1),1-13. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=82E7C62C5F1D4D14FCB3CA7E96D0DD2C?

doi=10.1.1.570.8462&rep=rep1&type=pdf [ Links ]

Sylvia, L. G., Peters, A. T., Deckersbach, T., & Nierenberg, A. A. (2012). Nutrient-based therapies for bipolar disorder: A systematic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(1),10-19. doi:10.1159/000341309 [ Links ]

The Center for Integrative Psychology. (2014). What is Integrative Psychology? Retrieved from http://www.centerforintegrativepsychology.org/ [ Links ]

Ventegodt, S. (2007). Biomedicine or holistic medicine for treating mentally ill patients? A philosophical and economical analysis. Scientific-World Journal 18,1978-1986. doi:10.1100/tsw.2007.287 [ Links ]

Whitmont, E. C. (1996). Alchemy, homeopathy and the treatment of borderline cases. The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 41,369-386. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1996.00369.x [ Links ]

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Boston, MA: Shambhala. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2013). WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [ Links ]

World Psychiatric Association. (2015). WPA Position Statement on Spirituality and Religion in Psychiatry. Retrieved from http://www.wpanet.org/uploads/Sections/Religion_Spirituality/Position_Statement_Spirituality_Psy-2015.pdf [ Links ]

Zhu, C. J. (2009). Analytical psychology and Daoist inner alchemy: A response to C.G. Jung's 'Commentary on The Secret of the Golden Flower'. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 54,493-511. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2009.01799.x [ Links ]

Zimmermann, E. B. (1996). Dança meditativa e caixa de areia associadas à análise verbal como técnica facilitadora de integração de processos simbólicos [Meditative dance and sandbox associated to verbal analysis as a facilitator technique for the integration of symbolic processes] (Doctoral dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, SP, Brazil). [ Links ]

Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Pamela Siegel

Rua Tessália Vieira de Camargo, 126

Campinas, SP, Brazil 13083-887

Fax: +55-1935218044

E-mail: gfusp@mpc.com.br and erturato@uol.com.br

Recebido: 16/09/2015

1ª revisão: 17/11/2015

Aceite final: 17/12/2015

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors. And both authors were responsible for the study conception and design; author # 1 performed the data collection and both authors performed the data analysis, were responsible for the drafting of the manuscript and made critical revisions to the paper for important intellectual content.