Obesity stigma, also referred to in the international literature as fatphobia, can be defined as the social rejection and devaluation of people who do not comply with prevailing social norms of adequate body weight and shape (Tomiyama et al., 2018). The literature shows that the etiology of obesity is complex and multifactorial, being influenced by a complex set of behavioral, environmental, biological and social factors. However, the misconception that obesity is an individual choice that is easily reversible with diet and physical activity prompts even greater blame and stigmatization of individuals with overweight (Rubino et al., 2020).

Weight-based prejudice has a negative impact on the health of individuals with obesity, as the stress of stigmatization can trigger adverse physiological, psychological and behavioral responses, such as decreased inhibitory control and increased caloric intake, and maladaptive coping strategies, such as social isolation, limited engagement with care services, reduced physical activity and disordered eating behaviors (Tomiyama et al., 2018; Talumaa et al., 2022).

Obesity stigma is also related to increased risk of an array of chronic conditions and, ironically, heightens risk of obesity through multiple obesogenic pathways. As a result, social prejudice can be more harmful to health than obesity itself, while at the same time damaging the dignity, human rights and quality of life of these individuals, warranting efforts to combat stigma and discrimination (Puhl & Heuer, 2010; Tomiyama et al., 2018).

Despite framing obesity within biomedical concepts and evidence of the health consequences of stigma for individuals with obesity, the prevalence of weight bias among health professionals remains high. Studies show that perceptions and experiences of weight bias negatively influence engagement with and utilization of health services by individuals with obesity, highlighting disrespectful treatment, attribution of all health issues to excess weight, assumptions about weight gain and low trust and poor communication, leading to poor care and driving patients away from health services (Alberga et al., 2019).

In an attempt to reduce weight bias, a group of international experts, including representatives of scientific organizations, published an evidence-based consensus statement to inform health professionals, policymakers and the public about the issues involved in weight stigma and the etiology of obesity. This document recommended a concerted effort to promote educational, regulatory and legal initiatives designed to prevent weight stigma and discrimination (Rubino et al., 2020).

Despite the growing body of research on obesity stigma, a systemic review by Duarte and Queiroz (2022) assessing the effectiveness of interventions to reduce weight stigma highlighted several gaps, including scarcity of longitudinal studies, small number of intervention sessions and few follow-up studies. The authors suggested that interventions should address the multiple causes of stigma, actively involve the target population and use a diversity of results-based monitoring methods.

In view of the complexity of preventive intervention, Murta and Santos (2015) highlight that these initiatives should be carried out systematically to maximize feasibility, effectiveness and sustainability, ensuring measures are sensitive to context and attractive to the target group.

To this end, the literature describes different models for developing preventive health interventions. One of these is Intervention Mapping (IM) (Bartholomew Eldredge et al., 2016), which is known more as a protocol for planning health promotion interventions but can be applied to any situation in which behavioral change is the desired outcome. The protocol serves to map the path of intervention development, from recognizing a need or problem to identifying and testing potential solutions. It aims to provide health promotion program planners with a framework for effective decision-making at each step of intervention planning, implementation and evaluation (Kok et al., 2017).

IM describes the intervention planning process in six steps: (1) Problem analysis based on a needs assessment and the creation of a logic model of the problem; (2) Creation of matrices of change objectives based on the determinants of behavior and environmental conditions arising from the logic model of change; (3) Program design, selecting theory-based intervention methods and practical strategies; (4) Translation of methods and strategies into an organized program; (5) Plan for adoption, implementation and sustainability of the program; and (6) Program evaluation.

Considering the problem of obesity stigma and the need for evidence-based interventions to prevent and combat this problem, the aim of this study was to present the development of the first two steps of the IM protocol, consisting of the needs assessment to create the logic model of the problem and the logic model of change. These steps constitute the initial phase of the planning process for an intervention aimed at reducing obesity bias among health professionals.

It is important to highlight that, given the magnitude of the problem, one single intervention on its own is unlikely to be able to encompass all target groups. The present study therefore intends to contribute to the body of knowledge on this topic by exploring the multiple dimensions of obesity stigma at the macro, meso and micro levels, indicating different potential target groups for future research and focusing on the operational aspects of an intervention project to reduce obesity stigma among health professionals.

Method

Study design

Steps 1 and 2 of the IM protocol were undertaken drawing on the results of a narrative review of the relevant literature and semi-structured interviews with health managers and experts on the topic.

Study location

The interviews with health managers were conducted between August and November 2021 with managers from the Federal District Department of Health (SES-DF) involved in the planning of a pilot intervention study directed at health professionals working with obesity in public health services. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in the SES-DF offices and lasted an average of 60 minutes. The interviews with the experts were conducted online because the participants live outside the study location. The interviews lasted an average of 45 minutes.

Participants

The following inclusion criteria were used to select the health managers and experts: health managers working in the SES-DF with experience in the implementation of educational courses or programs and attending people with obesity; Brazilian researchers in the field of obesity stigma in the Lattes CV database who showed interest in participating in the study after email invitation. The needs assessment was performed by four SES-DF managers from different specialties involved in the coordination of care for patients with overweight and obesity and two nutritionists who are experts in the field of obesity and stigma.

Instruments

The needs assessment interviews with the SES-DF managers were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide consisting of questions designed to identify training needs related to the topic, experience from previous training courses, the manager’s interest in doing the proposed course, barriers to and enablers of staff adherence to professional training, course dissemination and certification strategies, and the ideal target group for training within the SES-D. The interviewees were also asked to express their ideas about the proposed course.

The interviews with the experts were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide explaining the purpose of the project and asking for their views on course content, methodology and evaluation methods. The interviewees were also asked to mention any other aspects they felt were relevant to the project.

Procedures

The aim of the literature review was to identify the determinants of obesity stigma at macro, meso and micro levels to include in the logic model of the problem (Step 1). Searches for descriptive studies of “stigma” and “obesity” conducted between 2010 and 2021 were performed on the following databases: SciELO, LILACS and PubMed.

The literature review and interviews were conducted concurrently with the aim of enhancing the planning and implementation of a future intervention aimed at reducing weight bias among health professionals.

After completing the first step of the protocol, the matrices of change objectives were created (Step 2). The matrices describe the changes to be addressed by the intervention and provide the basis for the selection of theoretical methods and the practical application of the next steps of the protocol. The product of the second step was the logic model of change.

The study findings therefore consist of a combination of the results of a literature review identifying key factors related to obesity stigma, the opinions of experts regarding key strategies for addressing the problem, and the suggestions of health managers for optimizing feasibility and adherence of the target group to the proposed project.

Data analysis

The articles selected for the narrative review were categorized according to theme and level (macro, meso and micro) for inclusion in the logic model of the problem. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and analyzed using the six phases of thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke (2006), a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data.

Results

These results integrate information from the literature review and interviews conducted with experts on the topic of obesity stigma and managers in the public health area.

Narrative literature review

Obesity stigma is influenced by the complex interaction of factors at the macro, meso and micro levels. With regard to macrosocial factors, part of a complex web of moral norms, weight stigma is historically, culturally and politically created and embodied by society (Setchell et al., 2017). Stigma is influenced by various narratives that converge towards practices and discourses, such as: (1) the social context, which involves the production of truths about what is deemed normal and abnormal; (2) the influence of the media on opinions in the social context; (3) scientific discourse and the assumption that body weight is entirely controllable; (4) the political context, which denies the negative influence of stigma on efforts to address obesity; and (5) the absence of legislation prohibiting weight-based discrimination.

In relation to the social context, stigma involves issues of power, where people (or institutions) set standards that are deemed normal and use them to deploy disciplinary practices for those considered abnormal (Setchell et al., 2017). In the field of health, these practices are manifested in the promotion of healthy lifestyles, building a collective imaginary based on what is normal and accepted, while at the same time deeming what is pathological and blameworthy (Rojas-Rajs & Soto, 2013).

These aspects cast light on the role of mass media in shaping and reinforcing stereotypes of obesity. The media promotes discrimination against people with excess weight in different ways, conveying messages that focus on individual behavior without addressing the complex root causes of obesity, stimulating the consumption of weight-loss products, and setting body standards (Stanford et al., 2018).

The joint consensus statement with recommendations to eliminate weight bias issued by Rubino et al. (2020) suggests that the media is a pervasive source of weight bias and that inaccurate framing of obesity and inappropriate images, language and terminology attribute obesity entirely to personal responsibility, increasing weight stigma. The widespread but unfounded assumption that body weight is totally controllable by lifestyle choices may therefore explain the low public support for coverage of anti-obesity interventions that go beyond diet and physical activity, regardless of their evidence base (Puhl & Heuer, 2010; Rubino et al., 2020).

From a scientific perspective, in an analysis of the Brazilian Obesity Guidelines, Paim and Kovaleskib (2020) showed that the discourse running through the document unquestionably reinforces the healthy slim bodies misconception - directly relating weight loss to better health - and reproduces weight-based stereotypes, increasing and perpetuating fatphobia. The conclusions drawn by the above analyses are worrying, because health guidelines are used in both policy planning and professional practice (Paim & Kovaleskib, 2020). The findings reveal that public health efforts neglect the fact that stigma is a barrier to the treatment of obesity, reducing the etiology of obesity to the diet-physical activity binary and disregarding other important factors and the harmful health effects of stigmatization (Paim & Kovaleskib, 2020; Rubino et al., 2020).

With regard to the treatment of obesity in Brazilian legislation, Rigo and Santolin (2012) found that most laws addressing the issue tend to view obesity as an individual problem, failing to consider social, contextual, historical and cultural aspects. Strategies to combat the issue focus on diagnosis and medical treatment, with laws that protect the social and constitutional rights of people with obesity being scarce.

Mesosocial causes of obesity stigma include environmental and organizational factors involving the workplace, education and healthcare settings where stigma occurs.

Stigma has been documented in schools and academic settings by studies on prejudice and/or bullying of students with obesity, revealing that, compared with students of lower body weight, adolescents with overweight or obesity are more likely to experience social isolation and relational, verbal, cyber and physical victimization. They are also more susceptible to developing mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression (Rubino et al., 2020).

Bandeira and Hutz (2012) suggest that actions to prevent bullying at school should include raising awareness of the problem among the school community (staff, parents, teachers, students and directors), mediated by actions that promote welcoming practices and emphasize the importance of respecting differences. Public policies should also focus on bullying prevention in schools and governments should invest in staff training and development to combat this problem.

Another important issue that should be discussed is weight-based prejudice and discrimination in the workplace. The literature shows that overweight and obese workers are stereotyped by employers and may face disadvantages when it comes to hiring, salaries, promotions and severance due to their weight (Puhl & Heuer, 2010). As mentioned above, laws that protect the social and constitutional rights of people with obesity are also scarce (Rigo & Santolin, 2012).

National and international studies show that the prevalence of weight stigma is high among health professionals (Tomiyama et al., 2018). Negative attitudes towards people with obesity from different types of health professionals impede care and drive these individuals away from health services, further harming the physical and emotional health of these patients (Alberga et al., 2019).

The microsocial factors involved in the stigmatization of obesity include individual aspects (individual stigma against people with obesity and self-directed stigma) and how these feelings are manifested in interpersonal relations, mediating attitudes and behaviors towards people with obesity.

As with other types of stigma, individuals with obesity can internalize weight stigma. Self-directed weight stigma can be defined as a process by which individuals endorse anti-fat attitudes and turn the stigma on themselves, anticipating social rejection and believing they have less value to society. Self-stigma has various adverse physical, psychological and behavioral effects, increasing unhealthy eating behaviors, reducing motivation to lose weight, lowering self-confidence and heightening self-blame (Lippa & Sanderson, 2013).

Analysis of interviews with health managers

The interviewees talked about their experience with staff training and development courses, since interventions aimed at reducing obesity stigma among health professionals in public health care settings can include continuous education for staff.

The managers were receptive to the idea of a continuous training and development program for health professionals focusing on the psychological and social aspects of obesity, and provided various suggestions for the project, as shown in Table 1, which presents the results of the thematic analysis of the interviews.

Table 1 Thematic analysis of the interviews with managers

| Main theme | Description of the theme |

|---|---|

| Lines of care in the SES-DF | Importance of creating specialized centers (secondary care) as an operational strategy for overweight and obesity care; reports on experiences with professional training provided in 2016, when this line of care was created. |

| Interest in doing the proposed course | Creation of the overweight and obesity care line as an important justification for carrying out new training courses to continue the work carried out under this policy, and the need to maintain continued staff training; importance of a motivated team for the smooth functioning of specialized centers; importance of welcoming and respectful care for patients with obesity. |

| Barriers and facilitators of staff adherence to a training course | Barriers: excessive workload of primary care staff. Facilitators: raise local manager awareness of the importance of professional training so they set aside staff time for participation in continuous training; greater adherence to a course promoted by the SES-DF than to a course promoted by a staff member; important to establish a dialogue with primary care staff regarding what they want from the course and to produce good course material to increase adherence. |

| Course dissemination and certification | Suggestion that the course should be disseminated by regional managers and executed via SES-DF education channels, which could provide certification; need to raise awareness among managers so they help to recruit staff. |

| Interest of the target audience in continuous training courses | Demand for continuous training courses offered by the SES-DF is strong, especially when participation is encouraged by line managers; importance of raising awareness among senior management so they set aside staff time for participation; importance of recruiting staff who can act as multipliers within health facilities. |

| Target audience of the course | Importance of working with primary care staff to ensure that patients are welcomed and supported from the moment they enter the health system; the course should involve all members of multidisciplinary teams involved in care for the patients with obesity, given that obesity care requires different specialties; discuss whether the course will only be offered to professional-level staff or whether it will also involve technicians; suggestion that the pilot course be carried out in specialized centers (secondary care). |

| Course format (online, in-person or hybrid) | Flexibility provided by online courses; in contrast, a lot of staff are tired of this format due to excess virtual commitments during the pandemic and such a complex topic is difficult to teach online, especially since it is not simply content-based and therefore critically reflexive and participatory methods (less presentation) would be more suitable; consensus that the hybrid format is the most suitable to the aims of the course; important that the course load is at least 20 hours to ensure certification and to have places where staff can clock in (electronic clock-in system); importance of promoting staff engagement during the course, such as activities to encourage self-expression, discussion of clinical cases, opportunities to share experiences; important to train multipliers. |

Analysis of interviews with experts in obesity stigma

The interviews with the two nutritionists contributed to the content of the intervention, aspects related to the care that should be taken when working with the topic of obesity stigma, and course format. The experts also raised other important considerations to be addressed during the development of the intervention. The topics discussed in the interviews are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Thematic analysis of the interviews with the experts

| Theme | Description of category |

|---|---|

| Power of voice and anti-fatphobia militance | Importance and challenge of listening to and including the perspective of people with obesity in actions to reduce stigma. Health professionals have power of voice because society legitimizes biomedical power. These professionals should therefore take responsibility for including people with obesity in the discussion about combating weight stigma. |

| Importance of initiatives to combat fatphobia | Discussion of the fact that most health professionals do not consider themselves to be prejudiced and that everyday practice may be wrong; importance of raising awareness about stigma among health professionals and shifting the approach to obesity at universities; need to discuss the political aspects of the medicalization of obesity with students and professionals. |

| Inclusion of ways of assessing explicit and implicit weight-based prejudice in the intervention | Importance of discussing measures of prejudice; use of instruments to assess explicit and implicit anti-fat prejudice suggested; importance of assessing social desirability bias. |

| Stigmatized social representation of nutrition professionals | Discussion of the stigmatized social representation of nutritionists, who are seen to punish those who do not eat healthy foods, and the importance of addressing this issue on the course. |

| Course format | Suggestion that hybrid formats can be more enriching than exclusively online courses since face-to-face interaction facilitates socialization, discussion of ideas and sharing of opinions. |

| Promote interpersonal contact between health professionals and patients with overweight to reduce fatphobia | Importance of promoting interpersonal contact between healthcare professionals and patients with obesity to make appointments more natural and ensure that professionals do not avoid necessary physical contact during clinical examinations or feel uncomfortable with the presence of patients with obesity. |

| Political aspects of individual responsibility and the pathologization of obesity | Importance of updating professionals on the multiple causes of obesity as a key strategy for reducing individual blame for obesity and consequently reducing stigma; importance of discussing social and collective factors influencing obesity, including purchasing power, education level, family life, housing and culture. |

| Alignment of professional’s expectations | Need to align health professional’s expectations regarding patient adherence and to discuss other health and behavioral factors not directly related to weight loss that should be considered when evaluating results. |

| Caution when prescribing weight-loss | Importance of caution when prescribing weight-loss (which can negatively influence patient health) and of paying attention to the risk this practice poses for the development of eating disorders. |

| Caution when choosing course name so as not to put staff off | Suggestion to not include the term prejudice in the course name as many professionals may not be interested in participating because they do not consider themselves to be prejudiced; create a more general title such as “Updates on obesity and public health”. |

| Flow of course content | Importance of broadly discussing obesity, detailing its multiple causes, and stressing that studies reveal a lack of positive results for restrictive diets and the need for a shift in the focus of treatment, before talking about stigma. |

| Discussion of diagnostic criteria for obesity | Importance of discussing diagnostic criteria for obesity, which remain based on Body Mass Index (BMI), and updating professionals on new evidence. |

| Disagreement regarding concepts associated with the “psychological aspects of obesity” | Need to clarify the differences between psychological aspectswhich can be risk factors for obesity, and psychological aspectswhich are consequences of obesity. |

| Suggestions of videos to be shown during the course | Suggestion to show previously tested videos on the topic that have shown good results in raising health professional awareness. |

| Suggestions of different ways of approaching the topic on the course | Suggestion on ways to approach the topic on the course, such as group activities to raise awareness using photos and positive and negative associations and post-activity discussions. |

Logic model of the problem

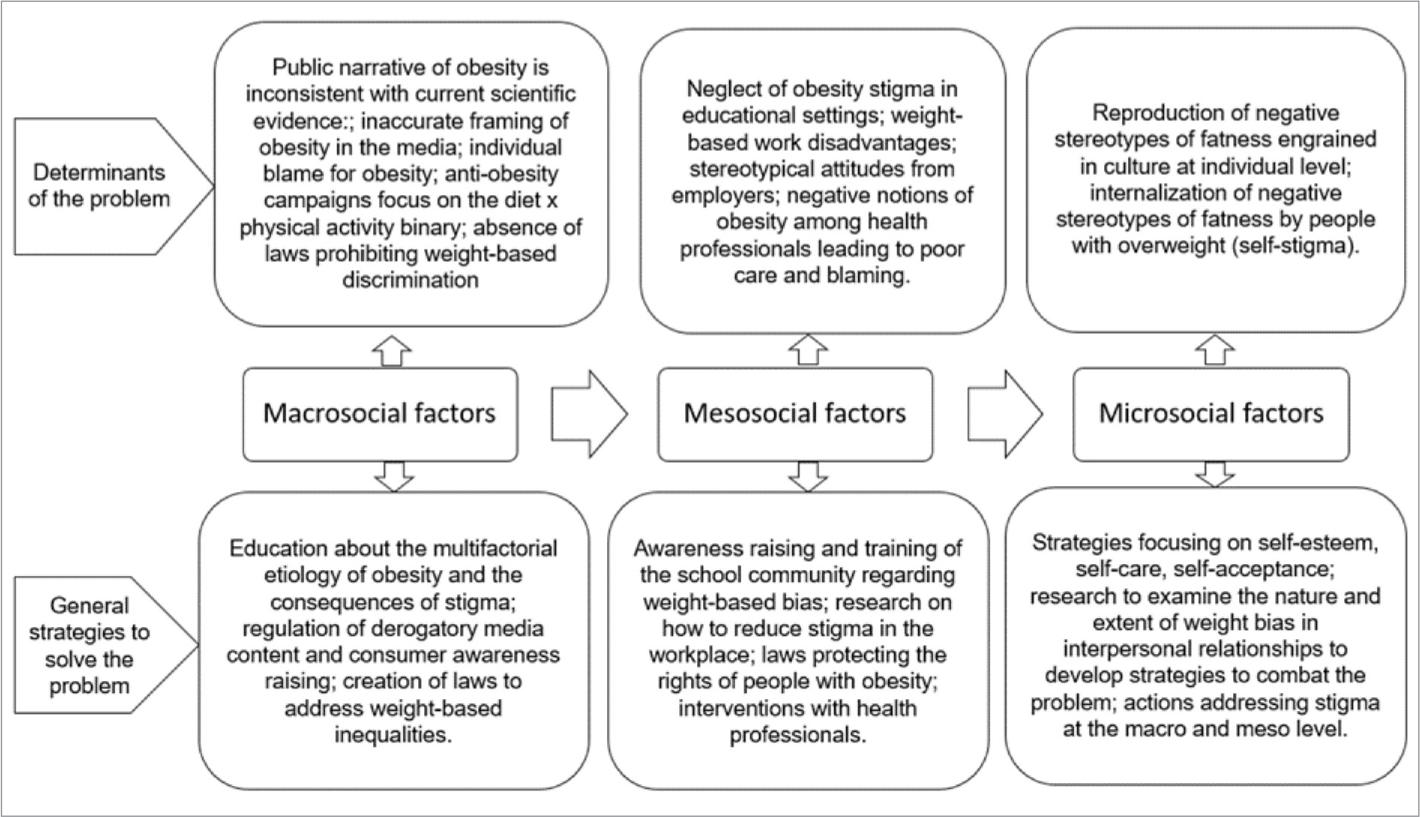

Figure 1 presents a summarized version of the logic model of the problem resulting from the integration of the results of the narrative literature review and interviews, both of which investigated the determinants of obesity stigma and strategies needed to modify them at the macro, meso and micro levels.

Logic model of change

The second step of IM is the creation of the logic model of change, which, based on the analysis of the determinants of the problem, describes the change objectives to be addressed by the intervention and the expected behavioral and environmental outcomes. The logic model of change, created after a thorough examination of the components in Figure 1, is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Logic model of change for interventions to reduce obesity stigma

| Macro level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Determinant of the problem | Belief, perception and behaviors to be modified |

Change objective | Expected outcome for thebehavior and setting |

| Public narrative of obesity is inconsistent with current scientific evidence: weight loss is prescribed by health professionals, and also by the media and society, without restriction. | Belief that weight loss is the solution to all health problems presented by people with obesity and that all fat bodies are sick; belief that weight loss improves the health of all bodies; Behavior: indiscriminate prescription of weight loss and discourse and disciplinary practices aimed at unrestricted weight loss for fat bodies. | Improve health professional’s understanding about the consequences of restrictive diets; disseminate the consequences of the indiscriminate prescription of weight loss in different media; promote a new public narrative of obesity that is consistent with current scientific evidence. | Prescription of weight loss only when there are clear health benefits; restraint on the prescription of restrictive diets by the media; increased knowledge about weight-loss methods not centered on restrictive diet; shift in the widespread belief that having a thin body is synonymous with health; end of disciplinary discourses and practices related to fat bodies. |

| Inaccurate framing of obesity in the media through inappropriate images, language and terminology, making the media a pervasive source of weight bias. | How the media conveys messages about fat bodies, and how it associates thin bodies with health and fat bodies with disease and other derogatory characteristics, such as laziness, cumbersomeness, greed and poor character. | Regulate and prohibit the derogatory portrayal of fat bodies by the media; include people with obesity in media images and messages depicting healthy behaviors; raise awareness among consumers about stereotypes in advertising. | Regulation of the publication of derogatory content by the media; inclusion of people with obesity in advertisements and various products; normalization of fat bodies in the media, without derogatory portrayal; increased consumer awareness of stereotypes in advertising; control of disciplinary messages about diet and exercise in the media. |

| Individual responsibility for obesity | Belief in personal responsibility for excess weight and disregard for the multifactorial etiology of obesity; disregard for the biological, social and environmental factors influencing obesity; lack of ability of professionals to provide comprehensive nutritional advice. | Promote an understanding of the multifactorial dimensions of obesity by providing training for health professionals in the multiple causes of obesity. | Increased dissemination of the complexity of the environmental and social aspects of obesity in academic institutions and the media; provision of welcoming and judgment-free health care. |

| Lack of awareness of the negative impact of obesity stigma on the health of individuals with overweight. | Belief that weight stigma positively influences people with overweight to lose weight; stigmatization is related to the influence of different social actors. | Recognize that obesity stigma negatively impacts the physical, emotional and social health of individuals with obesity. | Increased awareness about the consequences of weight stigma and reduction in stigmatizing discourse and practices across various social actors; improved mental health and quality of life; combatting obesity stigma is a public health priority. |

| Lack of laws to protect the social and constitutional rights of people with obesity. | Attributing obesity to individual responsibility removes the government’s responsibility for protecting the rights of individuals with obesity; creation of laws and policies to address weight-based inequalities. | Develop laws and implement policies to address weight-based inequalities. | Social rights of individuals with obesity recognized and protected in legislation. |

| Meso level | |||

| Determinant of the proble | Belief, perception and behaviors to be modified |

Change objective | Expected outcome for the behavior and setting |

| Lack of awareness and/or neglect of cases of weight-related stigma exercised by parents, teachers, staff and managers in educational settings. | Recognition of the presence of weight stigma in educational settings; shift from a passive to active stance on combatting bullying in educational settings. | Raise awareness about weight bias and cases of bullying among the school community (staff, parents, teachers, students and managers), promoting a culture of acceptance and respect for differences. | Attitudes towards preventing and combatting bullying in schools in keeping with public policies; investment in and training of education professionals to combat weight stigma in schools; welcoming and supportive educational environment and culture that combats prejudice and bullying. |

| Stereotypical attitudes and unequal treatment by employers in the workplace. | Belief that obesity hampers performance and leads to higher employment costs; unequal treatment of overweight people in the workplace. | Encourage intervention research to reduce obesity stigma in the workplace and identify effective strategies to address inequalities. | Equal opportunities and salaries for people with obesity; workplaces with a diverse staff base and institutional culture that promotes equal opportunities. |

| Micro level | |||

| Determinant of the problem | Belief, perception and behaviors to be modified |

Change objective | Expected outcome for the behavior and setting |

| Internalization of negative stereotypes about fatness by overweight individuals. | Self-directed stigma; self-esteem; self-compassion, self-care. | Treat self-directed stigma; cognitive restructuring; promote body acceptance. | Increased self-esteem, self-care and body acceptance. |

| Obesity stigma in interpersonal relationships. | Refusal to have romantic and/or sexual relations with people with obesity. | Reduce fat prejudice. | Greater diversity in relationships in different social contexts; acceptance of romantic and/or sexual relations and friendship with people with obesity. |

Discussion

This study developed the first two steps of the IM protocol (creation of the logic model of the problem and the logic model of change), constituting the initial phase of the planning of an intervention aimed at reducing weight bias among health professionals. The models were created based on the integration of the results of a literature review and interviews with health managers - emphasizing aspects related to project feasibility and execution - and experts in obesity stigma - who contributed to project content.

The findings reveal consistency between the results found in the literature and the themes recommended by the experts. Key issues highlighted were the assumption that body weight is entirely controllable and the need to raise awareness among health professionals and the public about the multiple factors (social, economic, cultural, political and biological) influencing the etiology of obesity. This issue is particularly important for two reasons: to stop individual blame for obesity, which is intrinsically linked to stigma, thus reducing stigmatizing attitudes; and to focus on other factors not related to the diet/physical activity binary in the treatment of obesity, as highlighted by the specialists:

“This course would need to ask: ‘What is obesity for you? What do you know about the causes?’ People may have ready-made answers [...] but at the end of the day they don’t even know how to explain or understand the mechanisms” (E1)

“There are a lot of missing pieces in university classes about obesity [...] nobody talks about the psychological, emotional, social issues, the whole context, that rarely happens” (E2)

In this respect, Rubino et al. (2020) suggest that research designed to elucidate etiologic mechanisms of obesity may not be perceived as a priority, with funding tending to be skewed towards the implementation of behavioral and lifestyle interventions, diminishing support for the investigation of novel prevention or treatment methods and investment in efforts that seek to curb weight stigma.

Another issue raised by the experts was the fact that the focus on the individual and behavioral aspects of obesity is related to the disciplining discourse espoused by health professionals. These professionals hold a strong voice in society and it is important to raise awareness among this group as to the responsibility that comes with this power and the need for an immediate shift in approach to professional practice in universities, as the following excerpt shows:

“We can see that society legitimizes biomedical power [...] That given, we can be more responsible and do our best, prompting discussion and being in this place of someone who is accountable for what they do, who’s not going to reproduce summer [weight-loss or exercise] challenges” (E1)

“Those diet therapy classes we have are just not on! It’s like: ‘the person’s obese, the persons got a BMI of I don’t know what, they need to go on a low-calorie diet, they need to do exercise, they’ll lose weight in I don’t know how many weeks’ [...] you have to take a deeper look”(E2)

In line with the interviewees, Alberga et al. (2019) found stigmatizing attitudes towards people with obesity across various health professions and in university students. The authors underline that these attitudes negatively affect the care delivered by these professionals and make patients feel marginalized, meaning they receive less preventive care. These observations highlight the need for interventions directed toward both health professionals and students.

The experts also emphasized the need to debate the medicalization of obesity with students and professionals. The interviewees highlighted that the process of medicalizing obesity has transferred responsibility from the government to health professionals. The latter feel frustrated with the poor results shown by patients, as behavioral measures alone fail to address the complex etiology of obesity, as the below example shows:

“You need to talk about the political aspects of individual responsibility, because professionals often fall for the idea that the individual is totally responsible for their situation, that people are only fat because they want to be, because they don’t have any discipline [...] And we know that often, when we aren’t able to control a social indicator, we medicalize it, because when we do that responsibility is personal. So professionals need to start thinking about social and collective factors, maybe even so they don’t feel so frustrated” (E1)

With regard to this issue, Francisco and Diez-Garcia (2015) suggest that the medicalization of obesity has contributed to the prevailing view that it is a choice, and caused by laziness, lack of willpower and other attributes that contribute to social rejection. The authors recommend that understandings of other mechanisms involved in obesity stigma should be included in training and be part of the everyday practice of health professionals.

One of the experts mentioned the importance of promoting interpersonal contact between health professionals and patients with obesity, especially when it comes to physical examinations, which, as described by Rubino et al (2020), are often avoided by professionals.

“Numerous fat people in Brazil may die because the doctor never carried out a physical examination; they didn’t want to. They say to the patient: ‘Go and lose weight’ and that’s it. My patient’s mother died of a perfectly detectable bowel cancer because she went to primary care services and they said: ‘Oh, go and lose weight’”(E2)

In a study examining the social roots and psychodynamics of prejudice, Oliva (2016) suggests that the contact hypothesis about reducing prejudice assumes that interpersonal contact between someone who is prejudiced and the person who is discriminated can bring to light similarities that help deconstruct the distorted reality that gives rise to prejudice. However, the author highlights that in cases of deeply ingrained, unconscious biases contact alone is not enough. Further research focusing on this hypothesis with regard to fatphobia is required to elucidate its effects.

Another key point addressed in the present study is the strategic vision of SES-DF managers related to project feasibility and factors likely to increase adherence of the target group. In this respect, the managers underlined that it is important to raise awareness among senior management and local managers of the need to set aside time in staff work schedules for training, help disseminate the program and encourage staff participation. It was also suggested that the course should have a minimum length of 20 hours and provide certification. The results show that the suggestions made by the managers and experts were complementary, with both groups emphasizing the importance of including different types of professions in training and suggesting that the most suitable course format is hybrid (online and in-person), with the adoption of active methodologies to promote discussion on the topics.

In this respect, Moran (2017) suggests that the integrated use of active methodologies and hybrid models can make an important contribution to solving current educational issues, since active learning methods emphasize the central and participatory role played by the learner and increase cognitive flexibility, helping to overcome rigid mental models and automatisms. In addition, the hybrid approach enables greater flexibility in terms of working hours and time management.

Other aspects such as the probable resistance of professionals to the topic were also discussed, suggesting an initial broad discussion of different aspects of obesity first followed by the issue of weight bias:

“As it’s a bit of a delicate topic, I don’t think we should go straight in with: ‘our aim here is to discuss the prejudice we often show’. It might create resistance. I think the course would need to include an update on the causes of obesity, on how difficult it is to treat, the fact that studies reveal that results are really poor even when the patient manages to diet [...] and then promote a more in-depth discussion on the social aspects of stigma” (E1)

In a study examining stigmatization and professional practice, Araújo et al. (2015) suggest that the focus of training for health professionals is essentially biological, warning of the need to include knowledge from the fields of social and human sciences to promote a broader debate about the prevailing dichotomy within the natural sciences.

This study also explored other factors influencing obesity stigma at the macro, meso and micro levels. One of the key macrosocial factors is the role the media plays in anti-fat bias. Rojas-Rajs and Soto (2013) suggest that the hegemonic model of health communication is underpinned by a predominantly positivist biomedical perspective, which focuses on the direct causes or etiology of disease, detached from the social dimension. This approach is structured around the idea that health depends on the prevention of destructive behaviors (risk behaviors) and adherence to protective behaviors. Discussions about this topic therefore focus on health communication for behavioral change, considering this approach an effective strategy for promoting healthy lifestyles, with people only being able to make lifestyle choices if they have the right information. The authors defend that, to have a greater impact on the target population, the field of health communication needs to evolve and adopt a broader perspective, especially when it comes to information on the social determinants of health.

It is important to note that despite the emphasis on health professionals, this study explored multiple factors influencing obesity stigma presented in the logic model of the problem and the logic model of change in Figure 1 and Table 3, respectively. These findings provide important inputs to inform the development of different interventions to reduce stigma across different settings and target groups. It is important to highlight, however, that there are gaps in research on interventions to reduce bias in other contexts - such as workplace and education settings, and the interpersonal aspects of stigma - and with other target groups - including children and adolescents and in society in general. Further research is also required on interventions directed at the reduction of self-directed stigma. In addition, there is a need for initiatives that address stigma in political contexts, the influence of the media and legislation to tackle weight-based inequalities.

Given the complexity of obesity stigma, this study systematically explored this topic in the light of Intervention Mapping to help researchers develop effective interventions capable of reducing this social prejudice, with emphasis on health professionals. The integration of research evidence and the contributions of health managers and experts - which are premises of the protocol - increase the chances of feasibility and effectiveness of interventions developed based on the results of this study.

texto em

texto em